This retrospective cohort study of 10,145 pregnant women noted seasonal influenza vaccine coverage increased from 38% to 63% between the 2008–2009 and 2010–2011 seasons and then dropped to 61% in 2011–2012. Vaccine coverage was higher in women considered at high risk of influenza complications, increasing from 43% in 2008–2009 to 71% in 2010–2011, before decreasing to 69% in 2011–2012. H1N1 vaccine coverage was greater than seasonal influenza coverage. The authors observed statistically significant differences in vaccination rates by trimester, gravidity, maternal age, and race/ethnicity

Abstract

Context:

Pregnant women are at increased risk of severe influenza-related complications and hospitalizations and are a priority group for influenza vaccination.

Objective:

To examine coverage of seasonal and pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccines in pregnant women in a managed care setting, from 2008 to 2012.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study of 10,145 pregnant women.

Main Outcome Measures:

H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccination rates.

Results:

Seasonal influenza vaccine coverage increased from 38% to 63% between the 2008–2009 and 2010–2011 seasons, and then dropped to 61% in 2011–2012. Vaccine coverage was higher in women considered at high risk of influenza complications, increasing from 43% in 2008–2009 to 71% in 2010–2011, before decreasing to 69% in 2011–2012. H1N1 vaccine coverage was greater than seasonal influenza coverage in 2009–2010 in the overall pregnant population (61% vs 53%) and in the high-risk group (64% vs 59%). We observed statistically significant differences in vaccination rates by trimester, gravidity, maternal age, and race/ethnicity.

Conclusions:

Vaccination rates increased significantly from 2008 to 2011, then dropped slightly in 2011–2012. Continued efforts are needed to ensure adequate vaccination coverage in this high-risk population.

Introduction

Pregnant women are at increased risk of severe influenza-related complications and hospitalizations.1–7 Physiologic changes in the respiratory, cardiovascular, and immune systems during pregnancy may contribute to this increased risk.8–10 In addition, women who are infected with influenza during pregnancy may have an increased risk of adverse outcomes such as preterm delivery, small-for-gestational-age infants, lower-birth-weight babies, and stillbirths.11–14 The inactivated influenza vaccine is considered both safe and effective to use during pregnancy.15–20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices have recommended that pregnant women receive seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccinations, regardless of trimester.21,22 There is also evidence that infants of vaccinated mothers have increased passive immunity, as well as significantly fewer influenza infections and hospitalizations than infants of unvaccinated mothers.6,20,23–25

Despite the recommendations of professional medical societies and good evidence for its benefits, influenza vaccination rates in pregnant women have historically been low.6 Before 2009, vaccination coverage in pregnant women ranged from less than 10% to 33%.17,26,27 Seasonal vaccination rates have risen dramatically since the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, with recent vaccination coverage rates during pregnancy reported at approximately 50%,27–29 but still fall well below the Healthy People 2020-recommended target of 80% vaccination coverage for pregnant women.30

The goal of this retrospective cohort study was to compare seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) coverage rates in pregnant women during four consecutive influenza seasons (2008–2009, 2009–2010, 2010–2011, 2011–2012), as well as the novel monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine (MIV) during the 2009–2010 influenza season. We also describe vaccination patterns observed by maternal factors such as high-risk medical conditions, trimester of pregnancy, gravidity, age at vaccination, and race/ethnicity.

Methods

We identified 13,975 pregnancies (of 12,036 women) that occurred during 4 consecutive influenza seasons, defined as October 1 through March 31 of each year (2008 to 2012) at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a managed care organization serving 470,000 members in Oregon and Washington. Of these, 11,086 pregnancies (10,145 women) met the following inclusion criteria: estimated date of delivery recorded in Health Plan databases, at least 12 months of membership in the year before October 1 of each influenza season, pregnant (1 to 41 weeks’ gestational age) at either of 2 vaccine index dates (MIV index date or TIV index date), and had a prenatal visit scheduled between the pregnancy start date and 40 weeks’ gestation. Pregnancy start date was calculated as 40 weeks before the estimated date of delivery.

Multiple pregnancy episodes (including pregnancies ending in live births, spontaneous abortions, and therapeutic abortions) during the study period were allowed, but the sample was unduplicated so that we did not select more than one pregnancy episode per woman per influenza season. In instances when a woman had more than one pregnancy episode per influenza season (n = 145), we selected the first episode for inclusion in analyses.

We obtained vaccination data from Health Plan databases and the Oregon state immunization registry.31 Most pregnant women in our Health Plan are vaccinated at influenza vaccination clinics, typically offered during October of each year, well before the usual peak of influenza in our community (typically January to February). However, a small number of women may be vaccinated at a prenatal visit, in a nurse treatment room, or outside the Health Plan.

We defined vaccine coverage as the total number of vaccinated pregnant women divided by the total eligible population of pregnant women. Eligible TIV and MIV populations were defined independently. For each population, we used the date of TIV or MIV vaccination recorded in the Health Plan database as index dates. We randomly assigned index dates to unvaccinated women, which matched the vaccination date distribution of vaccinated women in the relevant population. Women who were not pregnant on their TIV index date were excluded from TIV analysis, and those not pregnant on their MIV index date were excluded from the MIV analysis.

We defined trimester by weeks of gestation at the TIV or MIV index date (first trimester, 1 to 13 weeks’ gestation; second trimester, 14 to 27 weeks’ gestation; third trimester, 28 to 41 weeks’ gestation). Gravidity was defined as the cumulative number of pregnancies as assessed and recorded in the electronic medical record (EMR) by clinicians. This count includes the current pregnancy as well as prior pregnancies of any outcome. To ensure that the current pregnancy was counted, we selected the latest gravidity assessment between 8 weeks of gestation and the estimated date of delivery.

We defined high-risk status using medical record data from the year before each influenza season. We categorized women with ICD-9 codes for the following disease categories as high risk: chronic cardiac disease, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic renal disease, diabetes mellitus, hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, malignancies, metabolic diseases, liver diseases, and selected neurological/musculoskeletal conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

High-risk conditions for influenza complications

| High-risk category and subcategory | ICD-9 codesa |

|---|---|

| Chronic cardiac disease | |

| Acute rheumatic fever | 391–392 |

| Chronic rheumatic heart disease | 393–398 |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 402, 404 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 410–414 |

| Diseases of pulmonary circulation | 416–417 |

| Other forms of heart disease | 421, 423–425, 427.1–427.5, 427.8, 428–429 |

| Atherosclerosis, polyarteritis nodosa | 440, 446 |

| Congenital anomalies | 745–747 |

| Surgical/device conditions | V42.1, V45.0, V45.81, V45.82 |

| Cardiovascular syphilis | 093 |

| Candidal endocarditis | 112.81 |

| Myocarditis caused by toxoplasmosis | 130.3 |

| Chronic pulmonary | |

| Other metabolic and immunity disorders | 277.0, 277.6 |

| COPD and allied conditions | 491–496 |

| Pneumoconioses/other lung diseases caused by external agents | 500–506, 507.0–507.1, 508 |

| Other diseases of respiratory system | 510, 513–517, 518.0–518.3, 519.0, 519.9 |

| Congenital anomalies | 748.4–748.6, 759.3 |

| Lung transplant | V42.6 |

| Tuberculosis | 011, 012 |

| Diseases due to other mycobacteria | 031.0 |

| Sarcoidosis | 135 |

| Chronic renal disease | |

| Hypertensive renal disease | 403 |

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis | 581–583, 585–587, 588.0, 588.1 |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | 590.0 |

| Other specified disorders of kidney and ureter | 593.8 |

| Dialysis and transplant | V42.0, V45.1, V56 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250–251, 648.0 |

| Complications of diabetes | 357.2, 362.0, 362.11, 366.41 |

| Hemoglobinopathies | |

| Anemias | 282–284 |

| Immunosuppressive disorders | |

| HIV/Retroviral disease | 042–044, 079.5, V08 |

| Disorders involving immune mechanism | 279 |

| Diseases of blood and blood-forming organs | 288.0, 288.1, 288.2 |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 446 |

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 710.0, 710.2, 710.4, 714 |

| Organ/tissue transplants | V42.0–V42.2, V42.6–V42.9 |

| Radiation/chemotherapy | V58.0, V58.1 |

| Malignancies | |

| No subcategory | 140–208 |

| Other metabolic and immunity disorders | |

| Disorders of adrenal glands | 255 |

| Other disorders | 270, 271, 277.2, 277.3, 277.5, 277.8 |

| Liver diseases | |

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 571 |

| Liver abscess and sequelae of chronic liver disease | 572.1–572.8 |

| Neurological/musculoskeletal | |

| Psychotic conditions | 290, 294.1 |

| Mental retardation | 318.1, 318.2 |

| Hereditary and degenerative diseases of CNS | 330–331, 333.0, 333.4–333.9, 334, 335 |

| Other disorders of CNS | 340, 341, 343, 344.0 |

| Disorders of peripheral nervous system | 358.0, 358.1, 359.1, 359.2 |

| Late effects of CVD | 438 |

| Chondrodystrophy | 756.4 |

ICD-9 codes are listed using the least number of digits possible. Trailing digits are dropped when all codes using these digits are included. For example, the code 255 represents all codes 255.XX. Likewise the code 507.0 represents all codes 507.0X.

CNS = central nervous system; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.

The KPNW institutional review board reviewed and approved this study protocol. Because this was a retrospective, data-only study, informed consent was waived.

Results

The study population was 73% white. Mean maternal age at index date was 29.5 years, and mean gestational age was 20.3 weeks (Table 2). Most (60%) of the women had a history of 2 or fewer prior pregnancy episodes, and 86% of the participants were classified as having a normal influenza risk.

Table 2.

Demographic and maternal characteristics of study population

| Age at index date (N = 11,086 pregnancies)a | Mean ± SD |

| Maternal age, years | 29.5 ± 5.8 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 20.3 ± 11.6 |

| Ethnic category (N = 10,145 women) | Number (%) |

| Hispanic | 1113 (11.0) |

| Not Hispanic | 3559 (35.1) |

| Unknown | 5473 (53.9) |

| Racial categories (N = 10,145 women) | Number (%) |

| White | 7406 (73.0) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 917 (9.1) |

| Black or African American | 387 (3.8) |

| American Indian, Aleutian, or Eskimo | 75 (0.7) |

| Unknown | 1360 (13.4) |

| Gravidity (N = 11,086 pregnancies)a | Number (%) |

| 1 | 3208 (28.9) |

| 2 | 3021 (27.2) |

| 3 | 1965 (17.7) |

| 4 | 1071 (9.7) |

| ≥ 5 | 1069 (9.6) |

| Unknown | 752 (6.8) |

| Influenza risk status (N = 11,086 pregnancies)a | Number (%) |

| High risk | 1563 (14.1) |

| Normal risk | 9523 (85.9) |

Maternal age, gravidity, and influenza risk status were assessed for each pregnancy episode. Individual women were counted more than once if pregnant in multiple seasons.

SD = standard deviation.

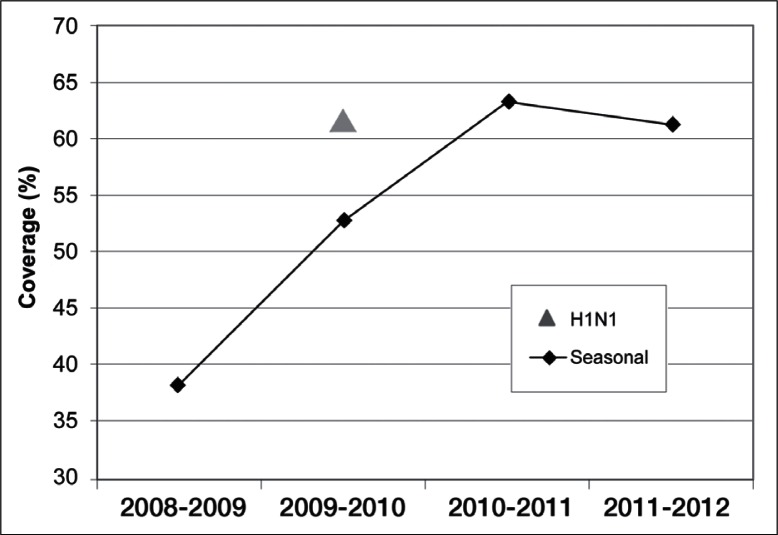

In the total population of women, TIV coverage increased by 25 percentage points between the 2008–2009 and 2010–2011 influenza seasons, and then dropped slightly during the 2011–2012 influenza season (Figure 1). Coverage rates during the 2008–2009, 2009–2010, 2010–2011, and 2011–2012 seasons were 38%, 53%, 63%, and 61%, respectively. Rates of MIV coverage during the 2009–2010 influenza season were higher than rates of TIV coverage that year (61% vs 53%).

Figure 1.

Seasonal and H1N1 influenza vaccination coverage rates, by influenza season.

Triangle = H1N1 influenza vaccination (2009–2010 season only); diamonds = seasonal influenza vaccination.

Influenza vaccine coverage was even higher in women (N = 1563 pregnancies) classified as having high risk of influenza complications at the time of pregnancy (Table 3). The TIV coverage in the high-risk influenza group increased from 43% in 2008–2009 to 71% in 2010–2011, before declining slightly to 69% in the 2011–2012 influenza season. Likewise, MIV coverage (2009–2010) in the high-risk influenza group was 64%.

Table 3.

Maternal characteristics of vaccinated women, 2008–2012

| Characteristic | 2008–2009 | 2009–2010 trivalent influenza vaccine | 2009–2010 monovalent influenza vaccine | 2010–2011 | 2011–2012 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number/total (%) | p value | Number/total (%) | p value | Number/total (%) | p value | Number/total (%) | p value | Number/total (%) | p value | |

| Trimestera | 0.06 | < 0.0001 | 0.15 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| First (1–13 weeks) | 317/918 (35) | 379/899 (42) | 556/939 (59) | 525/900 (58) | 554/989 (56) | |||||

| Second (14–27 weeks) | 396/961 (41) | 469/876 (54) | 591/950 (62) | 553/887 (62) | 527/907 (58) | |||||

| Third (28–41 weeks) | 320/827 (39) | 498/780 (64) | 535/856 (63) | 596/858 (69) | 620/881 (70) | |||||

| Maternal agea,b | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.18 | 0.06 | |||||

| < 18 years | 26/67 (39) | 28/58 (48) | 35/70 (50) | 33/49 (67) | 45/60 (75) | |||||

| 18–25 years | 170/631 (27) | 244/575 (42) | 278/615 (45) | 300/507 (59) | 319/568 (56) | |||||

| 26–35 years | 676/1629 (42) | 872/1558 (56) | 1092/1676 (65) | 1067/1663 (64) | 1060/1721 (62) | |||||

| ≥ 36 years | 161/379 (42) | 202/364 (55) | 277/384 (72) | 274/426 (64) | 277/428 (65) | |||||

| Racec | 0.0002 | 0.0026 | 0.0004 | 0.41 | 0.27 | |||||

| White | 756/1917 (39) | 1008/1863 (54) | 1241/1995 (62) | 1246/1992 (63) | 1271/2106 (60) | |||||

| Black | 35/110 (32) | 52/97 (54) | 54/100 (54) | 58/95 (61) | 59/98 (60) | |||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 114/254 (45) | 116/208 (56) | 155/223 (70) | 155/233 (67) | 169/257 (66) | |||||

| Other/unknown | 128/425 (30) | 170/387 (44) | 232/427 (54) | 215/325 (66) | 202/316 (64) | |||||

| Ethnicityc | 0.0019 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0084 | 0.0016 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 578/1399 (41) | 569/979 (58) | 682/1027 (66) | 521/801 (65) | 437/689 (63) | |||||

| Hispanic | 93/280 (33) | 133/274 (49) | 185/304 (61) | 204/292 (70) | 214/310 (69) | |||||

| Unknown | 362/1027 (35) | 644/1302 (49) | 815/1414 (58) | 949/1552 (61) | 1050/1778 (59) | |||||

| Graviditya,b,d | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.0008 | 0.0025 | 0.0060 | |||||

| 1 | 266/665 (40) | 401/737 (54) | 510/809 (63) | 546/831 (66) | 549/847 (65) | |||||

| 2 | 264/662 (40) | 381/724 (53) | 476/769 (62) | 463/732 (63) | 478/786 (61) | |||||

| 3 | 154/410 (38) | 247/480 (52) | 323/508 (64) | 295/469 (63) | 339/536 (63) | |||||

| 4 | 78/239 (33) | 136/252 (54) | 160/273 (59) | 176/276 (64) | 145/265 (55) | |||||

| ≥ 5 | 84/251 (33) | 124/257 (48) | 134/270 (50) | 136/257 (53) | 156/272 (57) | |||||

| Risk for influenza complicationsc | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.0009 | 0.0007 | |||||

| Normal risk | 886/2362 (38) | 1129/2185 (52) | 1435/2360 (61) | 1410/2273 (62) | 1408/2350 (60) | |||||

| High risk | 147/344 (43) | 217/370 (59) | 247/385 (64) | 264/372 (71) | 293/427 (69) | |||||

Mantel-Haenszel χ2 Boldface numbers indicate statistically significant.

Maternal age and gravidity are assessed for each pregnancy episode. Individual women may have been counted more than once if pregnant in multiple influenza seasons.

Chi squared. Boldface numbers indicate statistically significant.

Eighteen percent of gravidity records were missing in the electronic medical record for influenza season 2008–2009.

Nearly all (94%) of the women in our study began their prenatal care during their first trimester. Our data show that women in later pregnancy were generally more likely to get the seasonal vaccination (see Table 3). Although seasonal vaccination rates during the first trimester increased from 35% to more than 50% during the study period, they were still consistently lower than vaccination rates during later pregnancy. There were no significant differences in MIV vaccination rates by trimester during the 2009–2010 influenza season.

Vaccination rates also differed significantly by maternal age and gravidity. During the 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 influenza seasons, the lowest vaccination rates were observed in the 18- to 25-year age group (see Table 3). There were no significant differences by age group during the 2 most recent influenza seasons. In general, higher gravidity (an individual’s total number of pregnancies) was associated with lower vaccination rates.

Vaccination coverage increased over the study period for all racial and ethnic groups. The largest increase in TIV coverage occurred in Hispanic women: from 33% in 2008–2009 to 69% in 2011–2012 (see Table 3). In women of known race, the largest increase was seen in black women, from 32% in 2008–2009 to 60% in 2011–2012. During the most recent influenza season studied, the highest vaccination rates were observed among Hispanic (69%) and Asian/Pacific Islander (66%) pregnant women.

Discussion

Vaccination rates in our population of pregnant women increased steadily over the first three influenza seasons during our study period, before declining slightly during the most recent influenza season. The coverage rates we observed are significantly higher than historic rates but are consistent with more recent reports of vaccine coverage.26–29 We found that rates of MIV coverage during the 2009–2010 influenza season were higher than for TIV coverage, suggesting that improved vaccination rates may have been spurred by increased awareness or concern about H1N1 infection, as well as by increased efforts on the part of clinicians and of our managed care organization to increase vaccination rates in this population.27 Table 4 summarizes a number of strategies our Health Plan has implemented over the past several years to improve influenza vaccination coverage during pregnancy, including patient reminders on after-visit summaries, clinician reminders on prenatal visit checklists, and clinician tools and reminders in the EMR.

Table 4.

Kaiser Permanente Northwest regional strategies for improving influenza vaccination coverage during pregnancy

| Date implemented | Description of strategy |

|---|---|

| 1997–1998 | Influenza immunization information was added as a standard “trailer” on after-visit summaries. Summaries are printed directly from the EMR at the end of ambulatory care visits. |

| June 2008 | Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology implemented a clinician checklist with reminder to recommend vaccination to pregnant women during influenza season (defined as November 1 to March 31). |

| March 2009 | Influenza vaccination became a “hard stop” in all inpatient admission order sets. A hard stop means the clinician must order influenza vaccination, note that the patient already received the vaccine, or provide a reason for not ordering the vaccine. |

| March 2010 | Implementation of a set of orders in the EMR for clinicians to use at the “New OB” (first prenatal) visit, including an order for seasonal influenza vaccination. |

| May 2011 | Implementation of a provider tool in the EMR flagging pregnant women who have not yet received influenza vaccination. |

EMR = electronic medical record.

More than 94% of the women in our study started prenatal care during their first trimester of pregnancy, allowing adequate opportunity for vaccination during early pregnancy. We observed improved coverage rates during the first trimester of pregnancy over the past 4 influenza seasons, which suggests increased awareness of the current guidelines emphasizing that all pregnant women should be vaccinated, regardless of trimester.21,22 Despite these improvements, during the most recent influenza season we still observed the highest coverage rates in the third trimester. Women often cite concerns about getting vaccinated in early pregnancy as a reason for not receiving influenza vaccines,26 a fact that supports the need for continued education for both clinicians and patients emphasizing vaccine safety in all trimesters.

Overall, we observed the lowest vaccination rates in the 18- to 25-year age group and in women with a history of more pregnancies. During the 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 influenza seasons, pregnant women age 26 years or older were significantly more likely to get vaccinated than younger women, a finding that is consistent with other published data on this subject.28,32,33 However, we found no significant differences by age during the 2 most recent influenza seasons studied.

Earlier studies have reported that white women are more likely to be vaccinated than women of other racial and ethnic groups.29,32,33 Interestingly, in our study population we consistently observed the highest coverage rates in Asian/Pacific Islanders during the entire study period, as well as Hispanics during the last 2 influenza seasons. We saw increases in vaccination coverage in all racial and ethnic groups, but we saw the largest increases in blacks (from 32% in 2008–2009 to 60% in 2011–2012) and Hispanics (from 33% to 69%), to the extent that coverage in these ethnic and racial groups is now on par with, or exceeding, coverage in other groups. Taken together, these findings suggest that outreach efforts in our Health Plan to improve vaccination coverage in pregnant women (including all age, racial, and ethnic groups) are having a positive impact, such that differences that once existed between groups of pregnant women are no longer as critical.

A major limitation of our study is that our population may not be representative of the general population of pregnant women. Specifically, our study population was predominately white. Furthermore, as members of a managed care organization, our population is more likely to receive earlier and more regular prenatal care than is the general population, thus increasing the opportunity for vaccination during pregnancy.

Conclusion

In summary, we observed significant improvements in influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant women over the past several influenza seasons. We saw higher rates of vaccination in women considered at higher risk of complications from influenza. Consistent with earlier studies, we also saw the highest coverage rates in later stages of pregnancy and in older pregnant women. However, age-related differences in vaccination rates appear to be decreasing over time, such that there were no significant differences by age during the two most recent influenza seasons. Our race/ethnicity findings were somewhat surprising in that coverage rates were fairly consistent across all groups during the most recent influenza season. The lowest coverage rates were observed during the first trimester and in women with a history of more pregnancies, suggesting that these groups of pregnant women may require additional encouragement from their clinicians and public health campaigns to receive influenza vaccination.

Finally, it appears that vaccination coverage in pregnant women may have plateaued, or may even be starting to decline, possibly because of decreasing concern or awareness about influenza as we get farther out from the 2009–2010 H1N1 pandemic. Continued efforts are needed not only to maintain recent improvements in vaccination coverage but also to continue progress toward the Healthy People 2020 target of 80% vaccination coverage in this high-priority group.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was reviewed and approved through the clearance process of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention before submission. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

Financial support for this study was provided in full by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vaccine Safety Datalink (200-2002-00732), through America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Dr Naleway has received research funding for projects other than this one from GlaxoSmithKline. The author(s) have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

To Go Unvaccinated

If he [my next-door neighbor] is to be allowed to let his children go unvaccinated, he might as well be allowed to leave strychnine lozenges about in the way of mine.

—Methods and Results, Thomas Huxley, 1825–1895, English biologist

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in pregnant women requiring intensive care—New York City, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Mar 26;59(11):321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creanga AA, Johnson TF, Graitcer SB, et al. Severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Apr;115(4):717–26. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d57947. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d57947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellington SR, Hartman LK, Acosta M, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) in 71 critically ill pregnant women in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.038. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, et al. Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Pregnancy Working Group. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8;374(9688):451–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, California Pandemic (H1N1) Working Group Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jan 7;362(1):27–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910444. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0910444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen SA, Kissin DM, Yeung LF, et al. Pandemic Influenza and Pregnancy Working Group Preparing for influenza after 2009 H1N1: special considerations for pregnant women and newborns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.048. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, et al. Pandemic H1N1 Influenza in Pregnancy Working Group Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010 Apr 21;303(15):1517–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.479. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cono J, Cragan JD, Jamieson DJ, Rasmussen SA. Prophylaxis and treatment of pregnant women for emerging infections and bioterrorism emergencies. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 Nov;12(11):1631–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060618. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1211.060618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamieson DJ, Theiler RN, Rasmussen SA. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 Nov;12(11):1638–43. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060152. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1211.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein SL, Passaretti C, Anker M, Olukoya P, Pekosz A. The impact of sex, gender and pregnancy on 2009 H1N1 disease. Biol Sex Differ. 2010 Nov 4;1(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-1-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2042-6410-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeil SA, Dodds LA, Fell DB, et al. Effect of respiratory hospitalization during pregnancy on infant outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S54–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.031. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P, Knight M, UKOSS Perinatal outcomes after maternal 2009/H1N1 infection: national cohort study. BMJ. 2011 Jun 14;342:d3214. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3214. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yates L, Pierce M, Stephens S, et al. Influenza A/H1N1v in pregnancy: an investigation of the characteristics and management of affected women and the relationship to pregnancy outcomes for mother and infant. Health Technol Assess. 2010 Jul;14(34):109–82. doi: 10.3310/hta14340-02. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3310/hta14340-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omer SB, Goodman D, Steinhoff MC, et al. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011 May;8(5):e1000441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events following administration to pregnant women of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Nov;205(5):473.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.047. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990–2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;204(2):146.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.050. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naleway AL, Smith WJ, Mullooly JP. Delivering influenza vaccine to pregnant women. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:47–53. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj002. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxj002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamma PD, Ault KA, del Rio C, Steinhoff MC, Halsey NA, Omer SB. Safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Dec;201(6):547–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.034. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vellozzi C, Broder KR, Haber P, et al. Adverse events following influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccines reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, United States, October 1, 2009–January 31, 2010. Vaccine. 2010 Oct 21;28(45):7248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.021. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 9;359(15):1555–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708630. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0708630 Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2009 Feb 5;360(6):648, Breiman, Robert E [corrected to Breiman, Robert F]. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMx090004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice ACOG Committee Opinion No. 468: Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Oct;116(4):1006–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fae845. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fae845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008 Aug 8;57(RR-7):1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eick AA, Uyeki TM, Klimov A, et al. Maternal influenza vaccination and effect on influenza virus infection in young infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Feb;165(2):104–11. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.192. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, et al. New Vaccine Surveillance Network Impact of maternal immunization on influenza hospitalizations in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.042. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puleston RL, Bugg G, Hoschler K, et al. Observational study to investigate vertically acquired passive immunity in babies of mothers vaccinated against H1N1v during pregnancy. Health Technol Assess. 2010 Dec;14(55):1–82. doi: 10.3310/hta14550-01. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3310/hta14550-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Receipt of influenza vaccine during pregnancy among women with live births—Georgia and Rhode Island, 2004–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 Sep 11;58(35):972–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Seasonal influenza and 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—10 states, 2009–10 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Dec 3;59(47):1541–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, 2010–11 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Aug 19;60(32):1078–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding H, Santibanez TA, Jamieson DJ, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—National 2009 H1N1 Flu Survey (NHFS) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.003. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Immunization and infectious diseases [monograph on the Internet] Washington, DC: Healthy People 2020; 2012. Oct, [cited 2012 Dec 12]. Available from: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarthy NL, Gee J, Weintraub E, et al. Monitoring vaccine safety using the Vaccine Safety Datalink: utilizing immunization registries for pandemic influenza. Vaccine. 2011 Jul 12;29(31):4891–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.003. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldfarb I, Panda B, Wylie B, Riley L. Uptake of influenza vaccine in pregnant women during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.007. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steelfisher GK, Blendon RJ, Bekheit MM, et al. Novel pandemic A (H1N1) influenza vaccination among pregnant women: motivators and barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6 Suppl 1):S116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.036. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]