Gallbladder volvulus (GV), or torsion of the gallbladder, is an uncommon surgical emergency. This article reviews the world literature related to GV. Lists of typical symptoms and clinical presentations are provided to allow clinicians to establish an accurate preoperative diagnosis. GV is frequently undiagnosed before surgical intervention. When the diagnosis has been established before operative intervention, expeditious laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed safely. Delays in diagnosis may mandate open cholecystectomy.

Abstract

Introduction:

Gallbladder volvulus (GV), or torsion of the gallbladder, is an uncommon surgical emergency. This article reviews the world literature related to GV. We examine the history of gallbladder torsion and highlight the critical constellation of presenting signs and symptoms, which guide the acute care physician and surgeon to accurate and timely diagnosis of GV before surgical intervention.

Methods:

A comprehensive review of all published cases of GV was performed using the National Library of Medicine (PubMed) database.

Results:

Lists of typical symptoms and clinical presentations are provided to allow clinicians to establish an accurate preoperative diagnosis.

Conclusion:

GV is frequently undiagnosed before surgical intervention. However, clinical presentation and associated radiographic findings can lead to an accurate diagnosis if the clinician is aware of this uncommon condition. When the diagnosis has been established before operative intervention, expeditious laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed safely. Delays in diagnosis may mandate open cholecystectomy if laparoscopic extraction is contraindicated because of undesirable sequelae of gallbladder necrosis, specifically perforation, bilious peritonitis, and hemodynamic instability.

Introduction

Gallbladder volvulus (GV), or torsion of the gallbladder, is an uncommon pathology that is often misdiagnosed. It is most frequently seen in women who are in their seventh and eighth decades of life.1 This report will review the world literature on GV. We hope to shed light on the diagnosis of GV by highlighting typical clinical presentations and imaging studies from eclectic case reports, thereby bringing this pathology to the attention of the international medical community. This clinical review is designed to improve the physician’s ability to make the correct diagnosis preoperatively. Understanding the pathophysiology and nuances of clinical presentations will minimize delays in diagnosis and the need for conversion to open cholecystectomy, which frequently arises when GV is discovered in the operating room.

Methods/Results

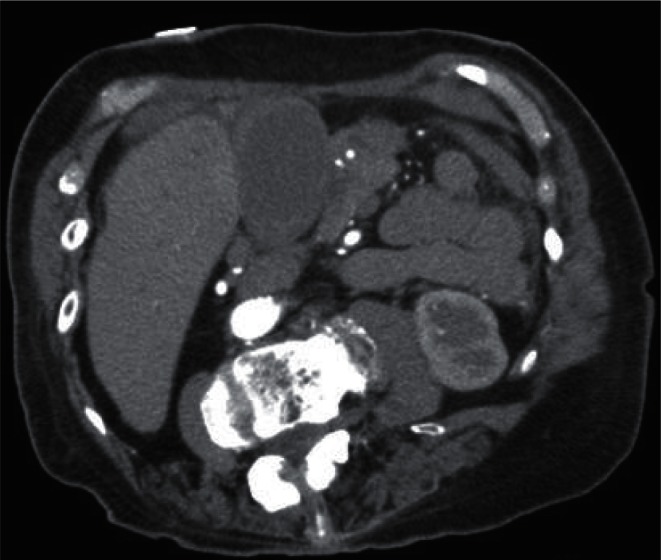

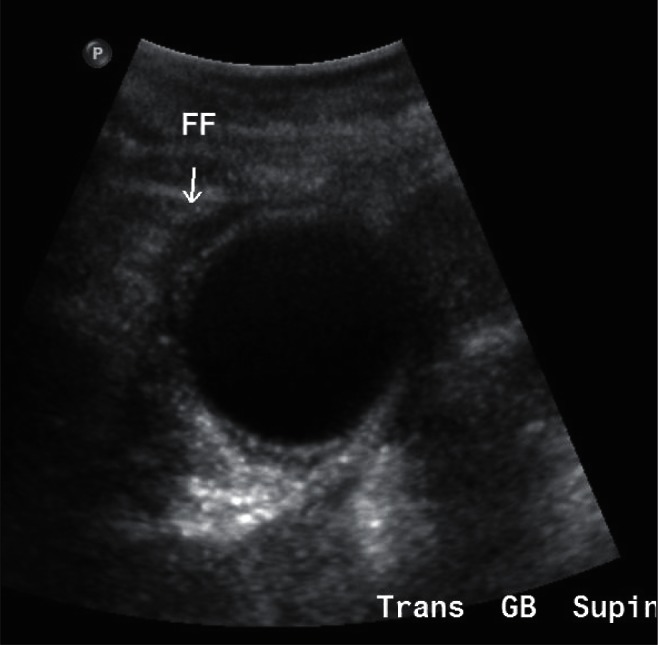

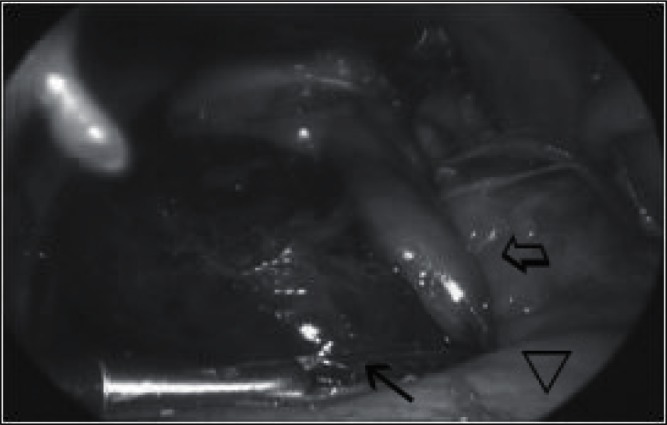

To review all known published case reports and case series, we searched the online database PubMed (National Library of Medicine) using the keywords “gallbladder volvulus” and “gallbladder torsion.” Table 1 presents data obtained from these sources. Figures 1 and 2 are typical of diagnostic findings on computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound. Figure 3 is an intraoperative photograph demonstrating the anatomical findings associated with this unusual torsion of the gallbladder. Figure 4 is a photograph taken during ex vivo examination of the infarcted organ.

Table 1.

Triad of triads used to recognize potential gallbladder volvulus1

| Appearance | Symptom | Physical examination |

|---|---|---|

| Elderly (usually female) | Sudden onset | Nontoxic presentation |

| Thin habitus | Right upper quadrant pain | Palpable right upper quadrant mass |

| Spinal deformities | Early emesis | Pulse-temperature discrepancy |

Lau WY, Fan ST, Wong SH. Acute torsion of the gallbladder in the aged: a re-emphasis on clinical diagnosis. Aust N Z J Surg 1982 Oct;52(5):492–4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1982.tb06036.x

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen with contrast, showing a thickened gallbladder wall and pericholecystic inflammation.

Figure 2.

Ultrasonogram of the gallbladder revealing pericholecystic fluid (FF).

Figure 3.

Clockwise volvulus along the mesenteric pedicle (hollow arrow) with an ischemic body (solid black arrow) displaced near the stomach (hollow arrowhead).

Figure 4.

Gallbladder specimen with ischemia distal to the point of transection.

Illustrative Case

A 79-year-old woman with a complex medical history including hiatal hernia, scoliosis, and papillary thyroid cancer presented to the Emergency Department for evaluation of acute right upper quadrant (RUQ) and epigastric pain. She had no antecedent symptoms, suggesting biliary tract disease. The pain was described as sharp, constant, and radiating to the chest. Deep breaths exacerbated the pain, which was unremitting. She denied emesis, acholic stools, dark urine, pruritus, jaundice, chest pain, scleral icterus, and shortness of breath. She had anorexia and nausea. Tachycardia was the only abnormal vital sign. Physical examination revealed a tender RUQ with a positive Murphy sign, but without rebound. Voluntary guarding was present. Findings of the remainder of the physical examination were unremarkable. Blood, laboratory, and imaging studies were performed, with the following results: leukocyte count, 8100, without a shift; hemoglobin, 13.2 g/dL; hematocrit, 39.2%; platelets, 151,000; total bilirubin, 0.5 mg/dL; lipase, 168 (normal range, 73–393); alkaline phosphatase, 104; and troponins, negative. An elevated D-dimer was noted, at 770 ng/mL. Given the pleuritic nature of the pain, elevated D-dimer, and cancer history, a CT angiogram was obtained and evaluated for pulmonary embolism. The CT angiogram was negative for an embolus but was significant for gallbladder-wall thickening with pericholecystic inflammation suspicious for acute cholecystitis (AC) (Figure 1). Therefore, an RUQ ultrasound was ordered. It revealed pericholecystic fluid, possible cholelithiasis, a gallbladder wall measuring 4.6 mm, and a common bile duct diameter of 7.7 mm, all of which suggested cholecystitis (Figure 2). The patient was admitted with a diagnosis of acute calculous cholecystitis, a carbapenem antibiotic was prescribed, and an urgent laparoscopic cholecystectomy was scheduled for that same day. Intra-operative findings revealed a uniformly ischemic gallbladder that had twisted along the cystic duct and artery pedicle in a clockwise fashion (Figure 3). Volvulus was identified and the pedicle was untwisted. An elongated mesentery and minimal peritoneal attachments were noted. A critical view was obtained before removal. Ex vivo examination of the gallbladder did not reveal cholelithiasis, despite suspected stone on ultrasound. Pathologic examination confirmed gangrenous cholecystitis without cholelithiasis (Figure 4). The patient recovered and was discharged to her home on postoperative day 1.

Discussion

GV was first described as a “floating gallbladder” by Wendel in 1898.2 This phenomenon is now recognized as a gallbladder that twists on its elongated mesentery. Since that early report, more than 500 cases have been reported in the world literature.3–10 The clinical incidence of GV has been reported as 1 in 365,520 hospital admissions.11 Multiple authors have postulated reasons for torsion of the gallbladder. Boonstra suggested that GV only occurs in the absence of gallbladder fixation to the liver.12 The term visceroptosis, referring to relaxation and atrophy of a previously normal mesentery in the elderly, has been used to describe this condition of mesenteric elongation and thinning, which is necessary for GV to occur.11,13–17 Atherosclerosis of the cystic artery and a tortuous cystic duct are also hypothesized as cofactors, as they may serve as fulcrums for gallbladder torsion.3,17 Other investigators have noted coexisting conditions that may predispose to GV. Nakao reviewed 245 cases in the Japanese literature, noting that GV tends to occur mainly in elderly women, although pediatric cases have been documented as well.14,17 A female preponderance has been established at a 3:1 ratio, with the highest incidence occurring in the seventh and eighth decades of life.14,16,18,19 Several other conditions are included among the list of risk factors associated with GV:

age > 70 years

female sex

weight loss

liver atrophy

kyphoscoliosis

atherosclerosis

elongated mesentery

loss of visceral fat, which results in the elongated gallbladder mesentery necessary for torsion to occur.16,19,20

Congenital anomalies that predispose individuals to elongated mesenteries have been reported, but these are unusual and undetectable preoperatively.19 Cholelithiasis is neither a prerequisite nor thought to contribute to mesoaxial torsion.14 In Nakao’s aforementioned review, only 24.4% of his patient population (N = 245) had coexistent cholelithiasis.14,19 The extent of torsion, measured in degrees, can be used to differentiate between complete (>180°) and partial (<180°) torsion.1,3,19 Incomplete volvulus may be misdiagnosed as biliary colic, whereas complete torsion produces unremitting, acute RUQ pain mimicking AC, and this ultimately results in infarction followed by perforation if not recognized promptly.1,3,19 Clockwise torsion has been attributed to gastric peristalsis, whereas counterclockwise torsion has been linked to colonic peristalsis.1,16 Christoudias hypothesized that GV arising from visceral peristalsis alone is unlikely, given that 5% of the population has a “floating gallbladder” and the peristaltic movements of the gastrointestinal tract are continuous.21 Regardless of rotational direction, blood supply is ultimately compromised, leading to infarction and gangrene.

GV is frequently misdiagnosed as acute acalculous cholecystitis, as no single clinical, serologic, or radiographic finding is pathognomonic.22 Knowledge of both clinical and radiographic findings typical of GV can facilitate accurate preoperative diagnosis. Table 1 lists three triads that suggest GV, as originally described by Lau et al.1,16,20 It is worth noting that a palpable RUQ mass is typically present with GV, but the “intraabdominal tumor” may be missed because of marked guarding.19 Serologic data can be equivocal during diagnosis and often mimic an acute inflammatory process. An important idiosyncrasy peculiar to GV is a lack of clinical or serologic improvement when the patient is admitted, treated with appropriate antibiotics, and adequately resuscitated for a presumed infectious etiology (ie, AC).16 When present, the unremitting symptoms support the diagnosis of GV. Ultrasound can reveal a clinical picture similar to that of AC, with a thickened wall and pericholecystic fluid (Figure 2).1,3 Although cholelithiasis visualized on ultrasound may also support a diagnosis of acute calculous cholecystitis, the assessing clinician must keep GV in the differential diagnosis, since ultrasound has a false-positive rate for gallstones of 3.9%.23 Multiple authors report that ultrasound can also be extremely specific in diagnosing torsion when the gallbladder is located outside of the fossa and inferior to the liver, presenting an echogenic conical structure.15,24,25 This image has been described as the wandering or pedunculated gallbladder.15,24,25 When color flow Doppler is used to visualize arterial blood, complete volvulus can be effectively eliminated.1 CT scans are usually nonspecific for diagnosing the disease. Merine et al stated that torsion is suggested by a distended gallbladder resembling a fluid-filled loop of bowel with a circular structure of high attenuation medial to the normal gallbladder location.26 Magnetic resonance imaging is valuable when diagnosing torsion because of its ability to reveal attenuated signal intensities indicating possible infarction, necrosis, or both.1,16 Such high-resolution images can reveal the volvulus.17 Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scans of GV are reported to resemble a bull’s-eye because of accumulation of radioactive tracer within the gallbladder.27

It is worth noting that a palpable RUQ mass is typically present with GV, but the “intraabdominal tumor” may be missed because of marked guarding.

Once GV is diagnosed, the appropriate treatment is emergency cholecystectomy.24,25 The cooling off (or stabilization) period often effected in cases of presumed cholecystitis is not appropriate for patients thought to have GV. Cholecystectomy can be performed via a laparoscopic or open technique. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for GV was first performed by Schroder and Cusumano, in 1994.28 Since then, multiple authors have treated GV via a laparoscopic approach, regardless of degree of torsion. Torsions of 1080° have been safely removed laparoscopically.29 Crucial steps involve decompression, detorsion, and obtaining the critical view during cholecystectomy.14 Meticulous dissection is essential, because the common bile duct may be at the anterior margin of the liver when twisted, making it susceptible to iatrogenic injury.21 Prognosis is excellent if expeditious cholecystectomy is performed. If treatment is delayed, infarction and perforation resulting in bilious peritonitis increase the mortality rate to approximately 5%.15,30

Conclusion

GV is a rare condition that requires an astute clinician with a heightened index of suspicion and low threshold for performing emergent cholecystectomy. This condition should be suspected in elderly patients presenting with RUQ pain whose clinical course and symptoms are refractory to antibiotic therapy and fluid resuscitation. Diagnosis will remain difficult despite improving technology, but recognition of the typical presentation described herein can lead to accurate preoperative diagnosis. GV mandates emergent cholecystectomy, to avoid visceral perforation, bilious peritonitis, and hemodynamic instability.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Attack the Gall Bladder

Obstruction, calculus, fullness and emptiness attack the gall bladder. The obstruction is either of the duct by which the bile is led away from the liver, or of that which it is discharged from the gall bladder into the intestine …. In both [the] feces [are] whitish [and] the bile diffused with the blood throughout the whole body disfigures the skin with jaundice.

—Jean-François Fernel, 1497–1558, French physician who introduced the term “physiology”

References

- 1.Garciavilla PC, Alvarez JF, Uzqueda GV.Diagnosis and laparoscopic approach to gallbladder torsion and cholelithiasis JSLS 2010January–Mar141147–51.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4293/108680810X12674612765588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendel AV., VI A case of floating gall-bladder and kidney complicated by cholelithiasis, with perforation of the gall-bladder. Ann Surg. 1898 Feb;27(2):199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caliskan K, Parlakgumus A, Koc Z, Nursal TZ. Acute torsion of the gallbladder: a case report. Cases J. 2009 Apr 29;2:6641. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-6641. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-0002-0000006641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amrani Y, Ounani M, Beavogui L, et al. [Gallbladder volvulus: two cases]. [Article in French] Presse Med. 2006 Oct;35(10 Pt 1):1479–81. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(06)74838-2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0755-4982(06)74838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron EW, Beale TJ, Pearson RH. Case report: torsion of the gall-bladder on ultrasound—differentiation from acalculous cholecystitis. Clin Radiol. 1993 Apr;47(4):285–6. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81142-0. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9260(05)81142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champault G, Lebhar E, Fichelle JM, Chevrel JP, Patel JC. [Volvulus of the gallbladder]. [Article in French] Med Chir Dig. 1977;6(8):559–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loizon P, Nahon P, Delecourt P. [Volvulus of the gallbladder in adults: apropos of a case]. [Article in French] J Chir (Paris) 1994 Nov;131(11):523–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sela M, Assa J. Acute volvulus of gallbladder and small intestine torsion. Int Surg. 1974 Mar;59(3):177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxter BT, Blackburn D, Payne K, Pearce WH, Yao JS. Noninvasive evaluation of the upper extremity. Surg Clin North Am. 1990 Feb;70(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stieber AC, Bauer JJ. Volvulus of the gallbladder. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983 Feb;78(2):96–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janakan G, Ayantunde AA, Hogue H. Acute gallbladder torsion: an unexpected intraoperative finding. World J Emerg Surg. 2008 Feb 22;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-3-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1749-7922-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boonstra EA, van Etten B, Prins TR, Sieders E, van Leeuwen BL. Torsion of the gallbladder. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012 Apr;16(4):882–4. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1712-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1712-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemonick DM, Garvin R, Semins H. Torsion of the gallbladder: a rare cause of acute cholecystitis. J Emerg Med. 2006 May;30(4):397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.07.011. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakao A, Matsuda T, Funabiki S, et al. Gallbladder torsion: case report and review of 245 cases reported in the Japanese literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6(4):418–21. doi: 10.1007/s005340050143. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s005340050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Fisher RF, Vargas-Ramirez L, Rescala-Baca E, Dergal-Badue E. Gallbladder volvulus. HPB Surg. 1993;7(2):147–8. doi: 10.1155/1993/34905. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/1993/34905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta V, Singh V, Sewkani A, Purohit D, Varshney R, Varshney S. Torsion of gall bladder, a rare entity: a case report and review article. Cases J. 2009 Nov 12;2:193. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-193. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-2-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura T, Yonekura T, Yamauchi K, Kosumi T, Sasaki T, Kamiyama M. Laparoscopic treatment of gallbladder volvulus: a pediatric case report and literature review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008 Apr;18(2):330–4. doi: 10.1089/lap.2007.0057. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/lap.2007.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Veken E, Azagra JS, de Prez C.Gall-bladder volvulus: a case report Acta Chir Belg 1986September–Oct865267–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaikh AA, Charles A, Domingo S, Schaub G. Gallbladder volvulus: report of two original cases and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2005 Jan;71(1):87–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau WY, Fan ST, Wong SH. Acute torsion of the gallbladder in the aged: a re-emphasis on clinical diagnosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1982 Oct;52(5):492–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1982.tb06036.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1982.tb06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christoudias GC.Gallbladder volvulus with gangrene. Case report and review of the literature JSLS 1997April–Jun12167–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malherbe V, Dandrifosse AC, Detrembleur N, Denoel A.Torsion of the gallbladder: two case reports Acta Chir Belg 2008January–Feb1081130–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker J, Chalmers RT, Allan PL. An audit of ultrasound diagnosis of gallbladder calculi. Br J Radiol. 1992 Jul;65(775):581–4. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-65-775-581. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-65-775-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safadi RR, Abu-Yousef MM, Farah AS, al-Jurf AS, Shirazi SS, Brown BP. Preoperative sonographic diagnosis of gallbladder torsion: report of two cases. J Ultrasound Med. 1993 May;12(5):296–8. doi: 10.7863/jum.1993.12.5.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagnato C, Lippolis P, Zocco G, Galatioto C, Seccia M.Uncommon cause of acute abdomen: volvulus of gallbladder with necrosis. Case report and review of literature Ann Ital Chir 2011March–Apr822137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merine D, Meziane M, Fishman EK.CT diagnosis of gallbladder torsion J Comput Assist Tomogr 1987July–Aug114712–3.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004728-198707000-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang GJ, Colln M, Crossett J, Holmes RA. “Bulls-eye” image of gallbladder volvulus. Clin Nucl Med. 1987 Mar;12(3):231–2. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198703000-00019. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003072-198703000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroder DM, Cusumano DA., 3rd Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder torsion. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995 Aug;5(4):330–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adelman MA, Stone DH, Riles TS, Lamparello PJ, Giangola G, Rosen RJ. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of Paget-Schroetter syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 1997 Mar;11(2):149–54. doi: 10.1007/s100169900025. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s100169900025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campione O, D’Alessandro L, Grassigli A, Pasqualini E, Marrano N, Lenzi F. [Volvulus of the gallbladder]. [Article in Italian] Minerva Chir. 1998 Apr;53(4):285–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]