Abstract

As new target-directed anticancer agents emerge, preclinical efficacy studies need to integrate target-driven model systems. This approach to drug development requires rapid and reliable characterization of the new targets in established tumor models, such as xenografts and cell lines. Here, we have applied tissue microarray technology to patient-derived, re-growable human tumor xenografts. We have profiled the expression of five proteins involved in cell migration and/or angiogenesis: vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1), protease activated receptor (PAR1), cathepsin B, and β1 integrin in a panel of over 150 tumors and compared their expression levels to available patient outcome data. For each protein, several target overexpressing xenografts were identified. They represent a subset of tumor models prone to respond to specific inhibitors and are available for future preclinical efficacy trials. In a “proof of concept” experiment, we have employed tissue microarrays to select in vivo models for therapy and for the analysis of molecular changes occurring after treatment with the anti-VEGF antibody HuMV833 and gemcitabine. Whereas the less angiogenic pancreatic cancer PAXF736 model proved to be resistant, the highly vascularized PAXF546 xenograft responded to therapy. Parallel analysis of arrayed biopsies from the different treatment groups revealed a down-regulation of Ki-67 and VEGF, an altered tissue morphology, and a decreased vessel density. Our results demonstrate the multiple advantages of xenograft tissue microarrays for preclinical drug development.

Keywords: Tissue microarray, angiogenesis, migration, β1 integrin, PAR1, MMP1, VEGF, cathepsin, HuMV833, gemcitabine

Recent advances in molecular medicine have deepened our understanding of the pathological basis of oncogenesis. This development has had far reaching consequences for drug development in oncology. Whilst traditional procedures for evaluation of drug efficacy are based on empirical screens measuring cytotoxicity, more recent algorithms emphasize additional aspects of malignancy such as angiogenesis, metastasis or signal transduction (1, 2). Nevertheless, the characterization of new target proteins and their validation for the clinic remains a labor intensive and time-consuming exercise. In order to ease this bottleneck, further research is urgently needed into the development of suitable high throughput methods.

Since their introduction in the late nineties, tissue microarrays have become a well established method for the parallel evaluation of gene and protein expression in hundreds of tissue biopsies (3). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry allow a classification of tissues according to gene expression, protein levels and histology. Moreover, the relationship between gene expression, pathological variables and clinical outcome data can be studied, which permits the assessment of the target’s relevance for therapy, diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. Thus, tissue microarrays have proven to be a valuable tool for the study of the human oncoproteome (3–4).

We have applied tissue microarray technology to our collection of human tumor xenografts. Over the past 20 years, our institute has established over 400 tumor models directly from patient explants which comprise >20 histologies and are growing subcutaneously in nude mice. They are available for in vitro (e.g. tumor colony assay) and in vivo evaluation of anticancer agents (5, 6). Tissue microarrays of the Freiburg human tumor panel allow simultaneous, objective analysis of target expression in several hundred different xenografts. Known clinical and pathological features as well as chemoresponsiveness can be correlated to the expression of the evaluated proteins. Target-dependent xenografts can subsequently be selected for in vivo testing of specific inhibitors, which increases the likelihood of correct tumor response prediction. Finally, pre-and post-treatment protein levels can be analyzed in parallel for target or marker modulation and proof of principle.

The modulation of tumor microenvironment for the inhibition of angiogenesis or metastasis has emerged as a promising approach for cancer therapy (7–9). Here, we have studied the expression of proteins involved in either migration and/or angiogenesis in >130 xenografts. We were able to identify highly positive and negative tumor models and to determine correlations between protein expression levels and patient outcome such as survival. Furthermore, using xenograft tissue microarrays in a “proof of concept” study, we have assessed the effects of the therapeutic monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody HuMV833 and gemcitabine on VEGF expression, Ki-67 and tumor morphology in two adenocarcinomas of the pancreas with different target levels that were treated in nude mice.

Materials and Methods

Human tumor xenografts

The Freiburg collection comprises over 400 human tumor models growing subcutaneously in athymic nude mice. In contrast to many other xenografts, the tumors were transplanted directly from the patients into 4 weeks old athymic nu/nu mice of NMRI genetic background. The patient explants have proven to be biologically stable, each tumor retaining the characteristics of the original neoplasia. Growth behavior, chemosensitivity patterns, molecular markers and histology of the xenografts were also shown to correspond closely to that of the original malignancy (5, 10–11).

The collection of tissues and information from cancer patients for the establishment of xenografts and patient sensitivity testing was approved by the University of Freiburg Ethics Board and patient consent was obtained. Clinicopathological variables were collected in an anonymized fashion in that patients were only identified by xenograft numbers.

Xenograft tissue microarrays

Microarrays were assembled from up to 150 paraffin embedded, formalin fixed human tumor xenografts by using a tissue microarrayer (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI, USA) (Table I). Fresh xenograft tissue was collected when tumors reached approximately 1.5 cm in size and immediately fixed in 10% PBS formalin for 24 hrs followed by routine processing and embedding into paraffin (3–4). Whole tumor sections (4 µm) were cut and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E). H&E sections of the xenografts were studied by light microscopy and representative areas marked on the slides. Xenograft biopsies, 0.6 mm in diameter, were taken from the corresponding area in the paraffin block and arrayed in duplicates into a new recipient block as described (3–4).

Table I.

Origin and histology of human tumor xenografts.

| Tumor Type | Number | Subtype |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder | 7 | Urethelial |

| Colon | 18 | Adenocarcinoma |

| CNS | 4 | 3 Glioblastoma, 1 Astrocytoma |

| Gastric | 6 | Adenocarcinoma |

| Head and Neck | 3 | Squamous cell |

| Lungs, non-small cell | 33 | Non-small cell (NSCLC) |

| adenoid | 14 | Adenocarcinoma |

| squamous cell | 6 | Squamous |

| large cell | 6 | Clear cell |

| Lung, small cell | 5 | Small cell (SCLC) |

| mixed | 2 | Mixed histology |

| Mamma | 15 | Invasive ductal and papillary |

| Melanoma | 15 | Mainly amelanotic |

| Ovary | 9 | Adenocarcinoma |

| Pancreas | 3 | Adenocarcinoma |

| Prostate | 6 | Miscellaneous |

| Mesothelioma | 7 | Biphasic and epithelial |

| Hypernephroma | 11 | Clear Cell |

| Sarcoma | 7 | Soft tissue and Osteosarcomas |

| Testes | 5 | Non seminoma |

| Cervix | 3 | Squamous |

| Leukemia | 2 | 1 Acute lymphoblastic, 1 acute myoblastic leukemia |

| Lymphoma | 1 | High grade, centroblastic |

| Liver | 4 | Hepatoma |

| SUM | 159 xenografts | |

CNS: Central nervous system.

Immunohistochemistry

Four µm sections of the microarray block were cut and transferred onto glass slides using the paraffin sectioning aid system (Instrumedics, Hackensack, NJ, USA). After rehydration, the endogenous peroxidase was blocked in 3% H2O2 solution. Antigen retrieval was accomplished through microwave pretreatment (20 min, at 100°C) in citrate pH 6.0 or Tris/HCl pH 10 buffers, depending on the primary antibody (Table II). The detection system employed was based on streptavidin-peroxidase-diaminobenzidine (and subsequent signal amplification with CuSO4 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) or strepavidin-peroxidase-Histogreen (Linaris, Wertheim, Germany). The arrays were stained with primary antibodies against cathepsin B, VEGF, the β1 subunit of integrin, matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) and protease activated receptor 1 (PAR1) (Table II). Mouse or rabbit IgGs were employed as negative controls, and the lectin bandeira simplicifolia agglutinin-I for specific staining of murine endothelium. Staining was analyzed by light microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert 100 Microscope, Darmstadt, Germany), according to the proportion of positive cells and intensity. A scoring system ranging from 0–3+ was used and the staining intensity evaluated by two independent observers.

Table II.

Antibodies and lectins used in histochemistry.

| Antibody/Lectin | Secondary antibody | Working dilution | Antigen retrieval buffer | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1integrin(Ab298) | Mouse monoclonal | Undiluted | Citrate (1 mM, pH=6.0) | BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA |

| Cathepsin B (IM-28L) | Mouse monoclonal | 1.40 | Citrate | Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA |

| Ki-67 (Ab-3) | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:50 | Citrate | Neomarkers, Fremont, CA; USA |

| VEGF (Ab-3) | Mouse monoclonal | 1:80 | Tris/HCl (10 mM, pH=10) | Neomarkers, Fremont, CA; USA |

| Bandeira simplicifolia | Lectin | 1:10 | Citrate | Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA |

| MMP1 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:200 | Citrate | Neomarkers, Fremont, CA; USA |

| PAR1 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:50 | Citrate | Acris, Hiddenhausen, Germany |

| IgG1, (X 0931) | Mouse | undiluted | Citrate | Merck, Darmstadt, Germany |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test and the Spearman rank order test as indicated. Distribution of survival time was visualized with Kaplan-Meier plots and compared to β1 integrin status using the Gehan-Breslow survival test. 91 patients with complete follow up were studied. The samples were dichotomized according to the proportion of β1 integrin stained cells. Tumors with a score of 1.0 or above (>33% positive cells) were considered as positive. We preferred this cut-off point to the median because the high proportion of negative findings (73% ) did not allow usage of the median, which was equal to zero. The “optimal cut-off approach” was not employed due to the high rate of false positive results (12–13). Tumor grade, cancer stage and the patient’s age were previously excluded as independent variables. All tests were two-sided. Differences or correlations of p-values <0.05 were considered significant. All computations were performed with SigmaPlot and SigmaStat software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

In vivo evaluation of anit-VEGF antibody HuMV833 and gemcitabine alone and in combination

Two human pancreatic tumor xenografts, PAXF546 and PAXF736, were implanted as 3×4 mm2 fragments in both flanks of female athymic nude mice (NMRI nu/nu strain). Animals were stratified according to tumor volume into 4 groups of at least 6 mice (PAXF546) or 3 groups of at least 3 mice (PAXF736). Each mouse had two tumors, one in each flank. Minimum tumor volume required at day 0 was 30 mm3 (4×4 mm2). Dosage, administration route and treatment schedule are displayed in Table III. When the agents were administered “simultaneously”, gemcitabine was given 10–20 minutes before injection of HuMV833 at day 0. Thereafter, each compound was given according to its standard schedule. The test substance HuMV833 was provided by Protein Design Labs (Fremont, CA; USA), gemcitabine was obtained from Eli Lilly (Bad Homburg, Germany). All animal experiments were performed in accordance to the German Animal Welfare Act and an approved institutional animal use protocol.

Table III.

Dosage and drug administration schedule used in the in vivo evaluation of HuMV833 and gemcitabine.

| PAXF546 |

PAXF736 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Dosage | Route | Schedule | T/C (%) | Growth Delay (days) |

T/C (%) | Growth Delay (days) |

| Control | 0.9% NaCl, 10 ml/kg | i.p. | Day 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 | 100 | - | 100 | - |

| HuMV833 | 100 µg/mouse | i.p. | Day 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32 | 36 | 2 | ND | ND |

| Gemcitabine | 300 mg/kg | i.v. | Day 0, 7 and 14 | 23 | 2 | 60 | 0 |

| HuMV883 + | as in | i.p. | HuMV833 as in single agent, | 10 | 19 | 50 | 1 |

| Gemcitabine | single agents | i.v. | until day 24 as in gemcitabine single agent | ||||

ND, not done; T/C, test/control.

Tumor volumes, relative tumor volumes, tumor doubling times and growth delays were calculated according to standard procedures (14). Growth curves were plotted according to the median relative tumor volume, and the growth inhibition was expressed as median relative tumor volume of the test versus control groups (treated/control % = T/C % ).

Xenograft tissues were collected from the treatment and control groups upon termination of the experiments and were organized in a separate tissue microarray for immunohistochemical evaluation of VEGF and Ki-67 expression. Lectin histochemistry with Bandeira simplicifolia was employed in order to identify murine endothelium (15).

Results

The markers analyzed in the present study were chosen to reflect some aspects of metastasis and angiogenesis. These multistep processes require, for example, attachment of tumor cells to the basement membrane, degradation of the local tissue, penetration and migration through the stroma. Proteases are involved in some of these processes and, thus, play important roles in tumor invasion and migration such as MMP1 (16) and cathepsin B (17). β1 integrin plays diverse roles including tumor invasion and metastasis (18). PAR1 is a G-protein coupled receptor. Activation of this protein leads to secretion of MMPs and increased cell motility (19). A different aspect is highlighted by VEGF. VEGF is involved in vascular formation and increased levels are associated with bad prognosis in the treatment of cancer (20).

Characterization of Cathepsin B

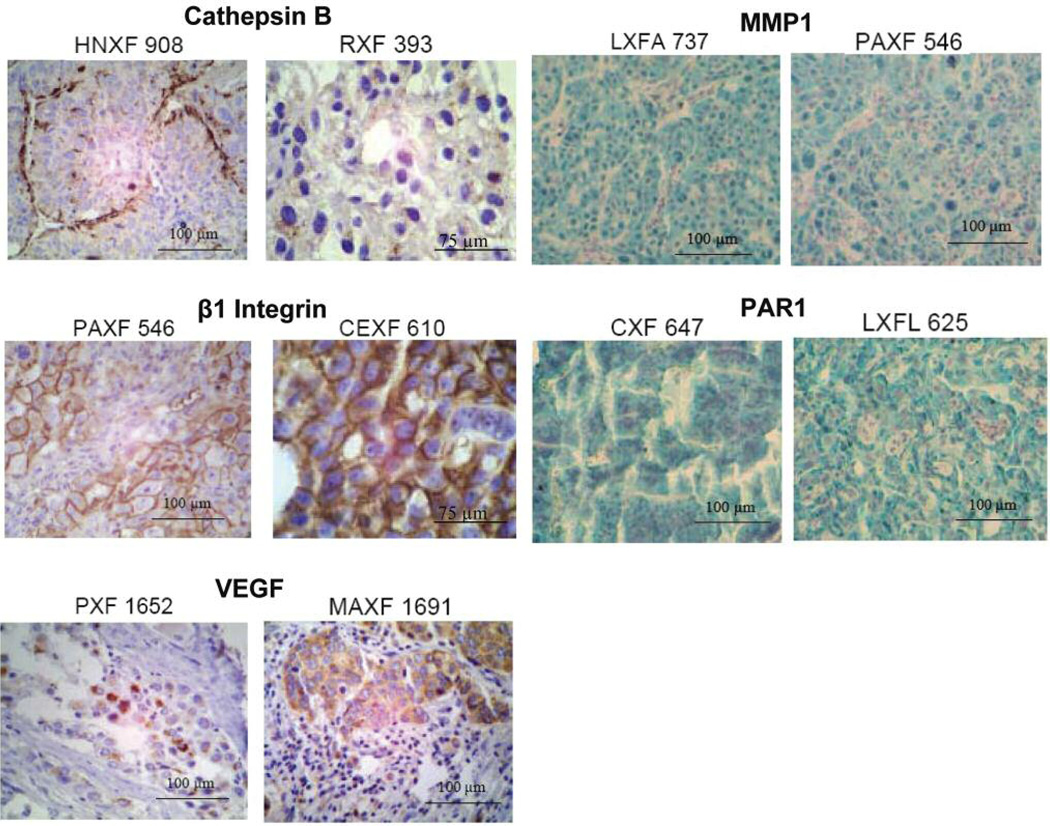

Expression of cathepsin B was evaluated in 150 xenografts. The mean staining intensity in all tumors was moderate (1.3±0.90). Staining of the enzyme showed a granular pattern (PXF393), consistent with the lysosomal localization of the enzyme. In some cases, cathepsin B was clearly overexpressed in cells adjacent to stromal tumor components (HNXF908, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Imunohistochemical staining of arrayed tumor biopsies. Cathepsin B showed a strong staining in the head and neck cancer HNXF908, especially along fibrous strands (score: 2.33±0.24). Lower levels of the protease were detected in renal cell cancer RXF393 (1.0±0.96). In the latter, granular expression was seen consistent with lysosomal localization. β1 integrin was localized on cell membranes as is shown for the pancreatic cancer PAXF546 (2.25±0.34), and the cervical cancer CEXF610 (3.0±0.00). VEGF showed a cytoplasmic distribution pattern, as evident in pleural mesothelioma PXF1652 (1.67±0.00) and in the breast cancer MAXF1691 (2.75±0.94). Cytoplasmic staining (green, nuclei blue) was observed for MMP1 (LXF 737, 2.5±0.35 and PAXF546, 2.75±0.35) as well as PAR1 (CXF647, 2.0±0.71 and LXFL625, 2.0±0.71).

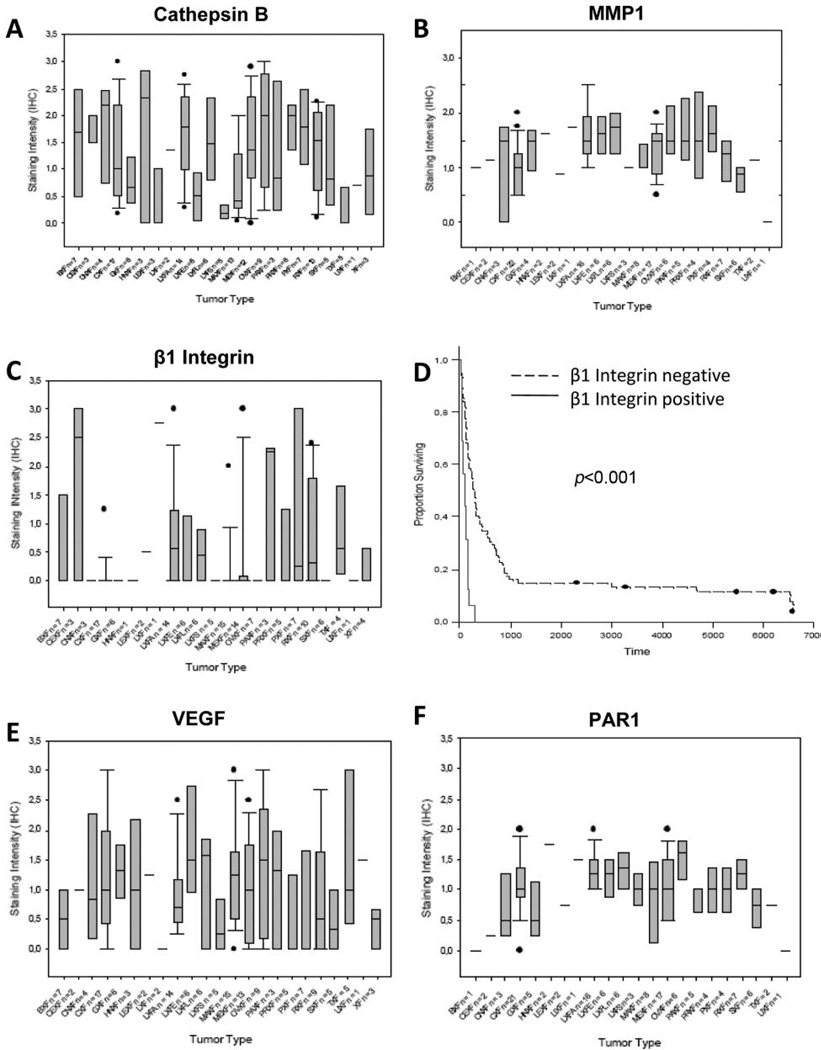

Cathepsin B levels were highly variable in most tumor types, e.g. melanomas, renal cell carcinomas and colonic cancers. Pleural mesotheliomas, urethral carcinomas, cancers of the prostate and lung adenocarcinomas, however, showed a high overall expression of the enzyme. Mammary carcinomas, gastric cancers, testicular cancers and small cell lung cancers (SCLC) had the weakest scores (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Mean staining intensities of cathepsin B (A), MMP1 (B), and β1 integrin (C); (D) Cumulative Kaplan Meier survival curve of 91 patients with different solid tumors. Patients with β1 integrin overexpression had a significantly worse prognosis than patients without (p<0.001). VEGF (E) and PAR1 (F) levels sorted by cancer type. The error bars represent the standard deviation.

Characterization of β1 integrin

147 xenografts were studied for β1 integrin expression. The majority of the cell membranes were stained in 16 tumors (>2/3 of the cells positive), whilst weak to moderate staining was observed in 24 tumors (1/3–2/3 cells positive). Figure 1 shows representative cases with membraneous staining. In most xenografts (n=107, 73% ), however, β1 integrin was not detected. Mean and median staining intensity were 0.45±0.85 (Figure 2C).

Three tumor types pleural mesotheliomas, lung adenocarcinomas and pancreatic cell carcinomas presented high levels of the integrin beta 1 subunit (Figure 2C).

When comparing the protein expresssion data of β1 integrin and cathepsin B a significant correlation was found (correlation coefficient =0.37; p<0.001).

Moreover, survival analyses showed a significant correlation between β1 integrin expression and prognosis. Overall survival was measured beginning at the first postoperative day. Follow up was available for 91 patients (62%). Seventy-five out of 91 patients presented undetectable or minimal integrin levels. Their median postoperative survival time was 286 days, 7 of these patients were still alive at time of study. Median survival time of patients affected with integrin expressing cancers was 101 days, which is significantly shorter than patients with low β1 integrin expression (p<0.001). None of them survived longer than 12 months (Figure 2D).

Characterization of VEGF

VEGF levels were studied simultaneously in 149 xenografts. As expected, staining was cytoplasmic (Figure 1). Mean staining intensity was 1.00±0.90, ranging from 0 to 3. We found a broad distribution of VEGF across all tumor types (Figure 2E).

Characterization of MMP1

MMP1 protein levels were evaluated in 127 samples. The mean staining intensity was 1.28±0.55 whilst the median was calculated as 1.25 (Figure 1, green). Staining ranged from 0 to 2.5, with only 5 tumors not showing any staining intensity at all. Staining above 1.5 was found in 34 samples (27%).

Tissues with high expression of MMP1 included head and neck, liver, ovaries, pancreas, pleural mesothelioma as well as some lung cancer subtypes (e.g. adenocarcinoma and large cell lung cancer; Figure 2B).

A correlation coefficient of 0.488 (p-value ≤0.001) was found when the protein expression of PAR1 and MMP1 were compared, i.e. when MMP1 is highly expressed so is PAR1.

Characterization of PAR1

The protein levels of PAR1 (thrombin receptor) were analyzed for 128 xenografts. Staining was predominantly found in the cytoplasm (Figure 1, green). The mean and median staining intensity were both 1.0 (the standard deviation was 0.49). Most staining was found to be moderate to low (108 samples) whilst 12 xenografts showed staining intensities above 1.5. The remaining 8 xenografts did not stain at all.

Tumor types that expressed PAR1 highly, included head and neck and ovarian cancers. Tumors of the urethral tract, colon, cervix and uterus showed low protein expression of the protein, but the low number of samples in some these tissues has to be noted (Figure 2F).

In vivo evaluation of HuMV833 on two pancreatic cancers

HuMV833 is a humanized monoclonal IgG4k antibody against VEGF. The effect of the original murine mAB, MV833, has previously been tested in human tumor cell lines and xenografts and shown promising results (21–22). Up to now, no information has been published about in vivo activity of HuMV833. Here, we have investigated the effect of the humanized mAB alone and in combination with gemcitabine in pancreas carcinoma, the standard cytotoxic used to treat this disease. The two pancreatic cancers, PAXF546 and PAXF736 with high and low VEGF expression and vessel density respectively were used. In our xenograft microarrays, VEGF levels were higher in PAXF546 than in PAXF736 (2.0 vs. 0.0). Similar results were found in an ELISA (VEGF PAXF546=20.7pg/up; PAXF736=4.4 pg/µg) and in studies on vessel density (data not shown). Both models are moderately to fast growing xenografts with a tumor doubling time of 4 (PAXF546) and 6 (PAXF736) days. HuMV833 did not show any toxicity in tumor bearing nude mice when administered intrapertianeally (i.p.) every 4 days at a dose of 100 µg/mouse.

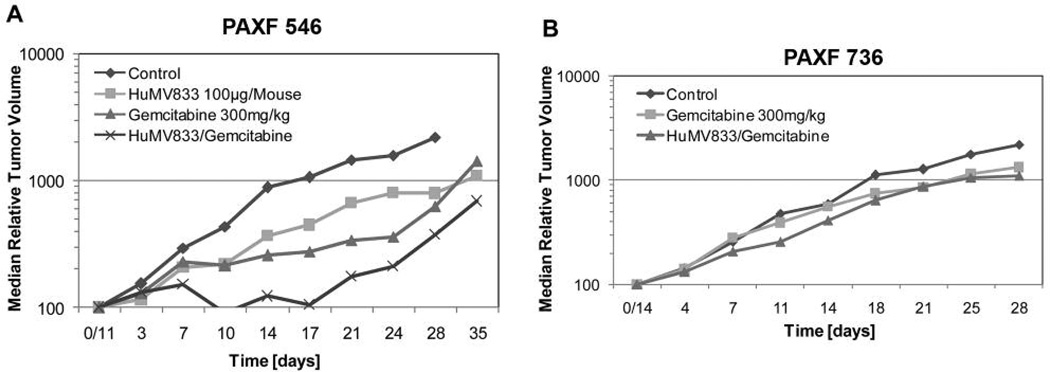

PAXF546

HuMV833 was active against PAXF546 with a T/C value of 36% and an absolute growth delay of 2 days (Figure 3A). The activity of gemcitabine was slightly better than that of HuMV833 (T/C 23% , absolute growth delay 2 days, Table III). Both compounds together however, significantly delayed the growth of the tumor compared to the vehicle control, and caused tumor regression (T/C 10% , absolute growth delay 19 days, Table III). The growth curve indicates that the tumor volume had regressed to 91% of the initial volume ten days after the start of the treatment, after which a gradual re-growth occurred (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Chemotherapy of pancreatic cancer xenografts PAXF546 with high VEGF (A) and PAXF736 with low VEGF (B). In both tumors, the combination of HumV833 and gemcitabine was the most potent. Sensitivity of PAXF546 was higher than that of PAXF736, which correlated with VEGF levels and vessel density.

The efficacy of the combination of gemcitabine and HuMV833 was higher than that of either compound alone. The T/C value of the combination was 10% and the absolute growth delay 19 days, indicating synergistic activity (Table III).

PAXF736

This tumor was less responsive to gemcitabine compared to PAXF546. It had a T/C value of 60% and no absolute growth delay. The combination gemcitabine + HuMV833 showed a marginal effect (T/C 50% , absolute growth delay 1 day; Figure 3B). HuMV833 monotherapy was not tested on PAXF736 because of lack of antibody supply.

In both tumors, the combination of gemcitabine and the monoclonal antibody was considerably better than that of gemcitabine alone and in PAXF546 also better than that of HuMV833. Furthermore, the combination of both drugs showed greater activity in the highly vascularized tumor PAXF546 than in the less angiogenic tumor PAXF736.

Post-therapeutic evaluation of target modulation in PAXF 546

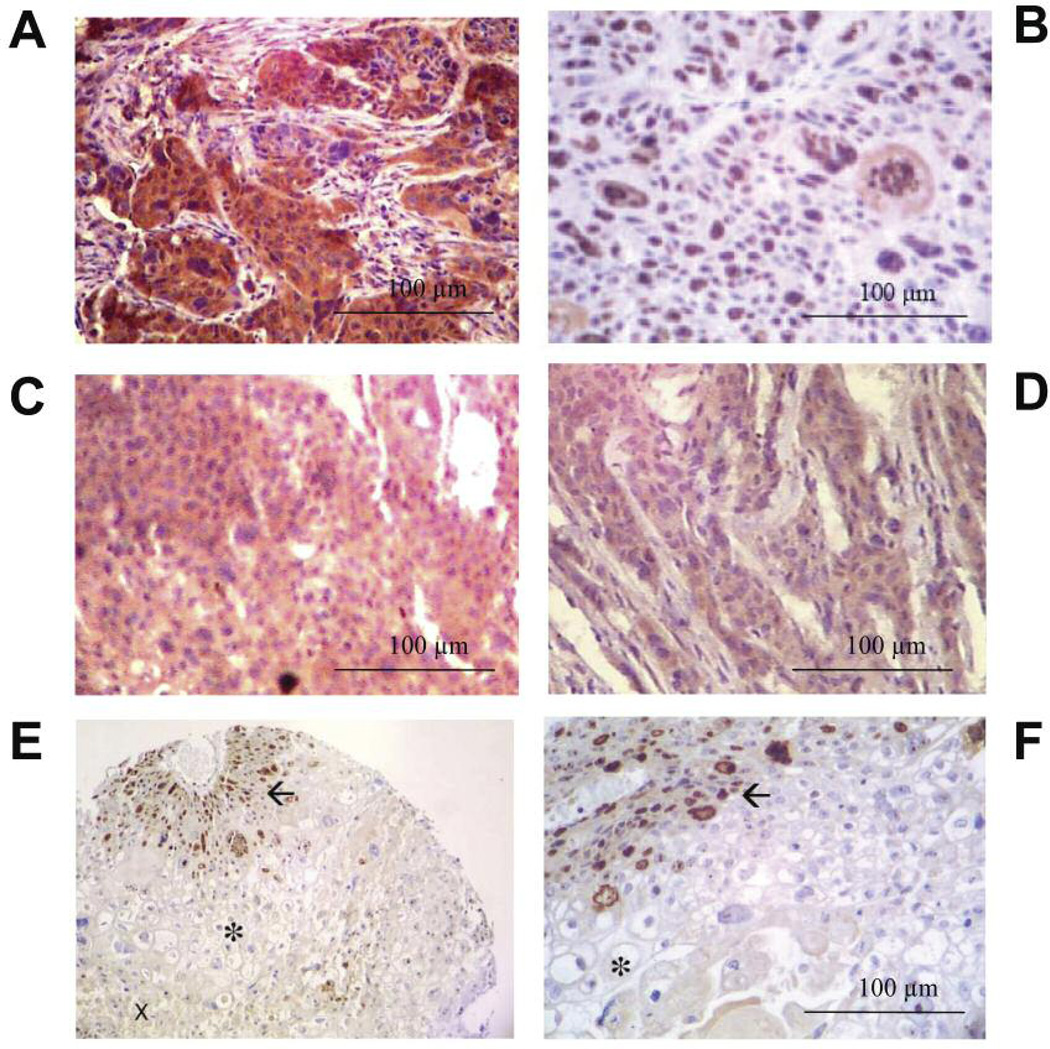

Following the in vivo studies (day 35 for PAXF546) xenografts of pancreatic PAXF546 were assembled in a tissue microarray. VEGF and Ki-67 expression were evaluated in 5 biopsies of each treatment group.

The control tumors were characterized by high VEGF levels (brown staining in Figure 4A) and a homogeneous distribution of nuclear Ki-67, indicating a rather even growth of cells within the xenograft (Figure 4B). We found different staining patterns in the other treatment groups, where VEGF expression was markedly lower (Figure 4C–D) and Ki-67 expression largely reduced to circular areas surrounding blood vessels (Figure 4E–F). Correct identification of the blood vessels was achieved by lectin staining of the murine endothelium (data not shown).

Figure 4.

PAXF546 showed high levels of VEGF (A) and a homogenous, nuclear expression of Ki-67 (B). In HuMV833 and HuMV833 + Gemcitabine treated pancreatic cancer PAXF546 (C and D respectively), VEGF expression was substantially lower compared to controls. Photos were taken from the same array slide as in Figure 4A. In HuMV833 + Gemcitabine treated pancreatic cancer PAXF 546 stained for Ki67, occurrence of vital cells was limited to small areas surrounding blood vessels (→) They were lined by cells with hydropic swelling (asterisk) and necrotic tissue (x). (E) magnification ×160, (F) Magnification ×400.

Discussion

In this study, we have examined the expression of five proteins involved in migration and/or angiogenesis: cathepsin B, β1 integrin, VEGF, MMP1 and PAR1, in up to 150 human tumor xenografts using tissue microarray technology. Furthermore, in a proof of concept study we have investigated the in vivo activity of a monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody and gemcitabine in two pancreatic cancers, and evaluated the therapeutic modulation of VEGF and Ki-67 in post-treatment tissues.

The basic characterization of the angiogenic proteins included overall occurrence, associations with tumor histology and prognostic significance. In the case of cathepsin B, a high expression was found in a wide range of tumors. Our results were congruent with cathepsin B mRNA data (r=0.48, p<0.001, n=94, data not shown). The degree of correlation was moderate, which might reflect the inherent posttranslational processing between mRNA and intracellular protein. Cathepsin B overexpression was found in pleural mesotheliomas, urethral carcinomas, cancers of the prostate and lung adenocarcinomas. Similar results have previously been described for the former three cancer types (23–25). No data has been published concerning the expression of the protease in mesotheliomas, however cathepsin B has several potential clinical applications. It has been proposed as a prognostic factor for several cancers (26–28). Thus, its inhibition may be of therapeutic interest. Furthermore, Marten and co-workers (29) have developed a procedure using cathepsin B – sensing molecular beacons in dysplastic intestinal adenomas for early tumor detection, whereas Eijan and co-workers have noted elevated urine levels of the enzyme in bladder cancer patients (23, 30–32). Our data point out that these new methods for diagnosis and treatment of cancer should best be developed in tumor models with high cathepsin B levels, such as pleural mesotheliomas or bladder cancers, for instance. We have identified 22 xenografts in our tumor collection with highly elevated cathepsin B levels. These might be employed for preclinical testing of compounds targeting the enzyme or polymer prodrugs such as polymeric prodrug N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer-Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly-doxorubicin conjugate PK1 that are aimed to utilize tumor associated proteases for specific release of cytotoxic agents in the tumor cell (32).

In contrast to cathepsin B, which was widely distributed, the overexpression of PAR1 was limited to only 9% of tumors evaluated. Tumor types showing high protein expression of PAR1 included head and neck and ovarian cancers. These two tumor types have previously been found to express high levels of PAR1 (33–35). However, there appears to be some controversy regarding the expression of the protein in metastatic and non-metastatic cells: Zhang et al. (34) reported that in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck metastatic tumors showed a lower expression of PAR1 whilst Liu et al. (35) found lower protein levels of PAR1 protein in non-metastatic cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. In endometrial cancers high mRNA and protein expression of PAR1 were found in high grade endometrial carcinomas (33). Boire et al. (36) showed that MMP1 is able to activate PAR1 by proteolytic cleavage. In addition, it was proposed that MMP1 derived from host tissue can cleave PAR1 expressed by tumor tissue (37). Therefore it was interesting for us to investigate the protein expression levels of MMP1. MMP1 is a member of the matrix-metalloproteinase family acting as a collagenase. In accordance with the findings of Boire et al., the protein expression levels of MMP1 and PAR1 correlated significantly. High protein expression of MMP1 was found in over 25% of samples investigated. Tissues expressing high levels of MMP1 included oesophagus, ovaries, pancreas, pleural mesothelioma and some lung cancers. These tissues have been previously reported to show high levels of MMP1 (38–43). Although several studies have shown MMP1 expression to negatively correlate with survival in a wide variety of cancers (reviewed in 43), a comprehensive comparison of various cancer types does not appear to have been carried out so far, making the present investigation the first of its kind.

Beta 1 integrin overexpression was limited to 11% of the examined tumors. Similar frequencies of β1 integrin overexpression have been described in ovarian cancers (16% ) and urethral cancers (22% ) (44–46). Our study is the first to describe elevated β1 integrin levels in cancers such as renal cell carcinomas, cervix cancers, and pleural mesotheliomas. Considering the limited number of examined tumors, however, our results have to be interpreted carefully. Although the role of the integrin subunit in tumor angiogenesis and invasion is certain, its prognostic significance remains controversial (47–49). In the present study, information on patient survival and β1 integrin expression was available in 91 cases. Our findings suggest that β1 integrin has a profound impact on the postoperative course of cancer patients, but more extensive studies will be needed for confirmation.

In this context, we were able to use tissue microarray technology for basic characterization of little known proteins in view of future clinical applications. Tissue microarray data might provide first indications, which can be used as a starting point for more extensive studies.

A second, essential aspect of our work is the availability of the studied tumor material for in vitro and in vivo studies. This represents a major advantage over traditional tissue arrays using archived, non-regrowable material. Here, we have analyzed VEGF expression in 149 xenografts, including three pancreatic cancer xenografts. Two were selected for studying antitumor activity of an anti-angiogenic regimen, a monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody and gemcitabine. VEGF levels measured by immunohistochemistry in the tissue microarray and by ELISA as well as vessel density were higher in PAXF546 than in PAXF736. Accordingly, PAXF546 showed a better response to treatments than PAXF736, the latter one being resistant to anti-angiogenic therapy. If the results of this study can be extended, VEGF synthesis and vessel density could be utilized for the selection of patients potentially sensitive to gemcitabine and the clinically available anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (Avastin) or small molecule VEGF inhibitors such as sunitinib (Sutent).

Following the in vivo trials, we investigated the modulation of VEGF in PAXF546. Results of simultaneous staining of the samples in the microarray showed a clear decrease of VEGF levels in the treated tumors. Clarification of the underlying molecular mechanism was beyond the scope of our study. However, it might be presumed that intracellular VEGF vesicles were depleted following continuous hypoxic stress due to VEGF inhibition. A decrease of VEGF activity might also explain the lower vessel density and the appearance of large necrotic areas found in the treated xenografts. Even though necrosis commonly occurs in untreated cancers, comparison of vessel density showed a significant difference between the treatment groups. Moreover, Ki-67 stains illustrated the altered microanatomy of the tumor, revealing disseminated vital tissue islets adjacent to a blood vessel and surrounded by hydropic and necrotic cells. These observations underscore the potential use of tissue microarrays for mechanistic and proof of principle studies.

In summary, tissue microarrays provide valuable information for target-orientated drug discovery. It is a method that allows the simultaneous evaluation of many different samples under exactly the same conditions saving on sample material and reagents. Although the present studies have focused on proteins involved in migration and angiogenesis, other areas are just as amenable. Therefore, tissue microarrays should be considered when investigating potential targets.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andre Korrat for his help and support with the statistical analyses of the data.

This work was supported in part by grants QLG1-1999-01341 from the European Commission and 01GE9919 from the German Ministry for Research and Education (BMBF) to AMB.

References

- 1.Burger AM. Highlights in experimental therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 2007;245:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger AM, Fiebig HH. Preclinical screening for new anticancer agents. In: Figg WD, McLeod HL, editors. Handbook of Anticancer Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 2004. pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kononen J, Bubendorf L, Kallioniemi A, Bärlund M, Scraml P, Leighton S, et al. Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat Med. 1998;4:844–847. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voduc D, Kenney C, Nielsen TO. Tissue microarray in clinical oncology. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2008;18:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiebig HH, Maier A, Burger AM. Clonogenic assay with established human tumor xenografts: correlation of in vitro to in vivo activity as a basis for anticancer drug discovery. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:802–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiebig HH, Berger DP, Winterhalter BR, Plowman J. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of US-NCI Compounds in human tumor xenografts. Cancer Treat Rev. 1990;17:109–117. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(90)90034-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidler IJ, Ellis LM. The implications of angiogenesis for the biology and therapy of cancer metastasis. Cell. 1994;79:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15–18. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumourhost interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–379. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger DP, Winterhalter BR, Fiebig HH. Establishment and characterization of human tumour xenografts in thymus-aplastic nude mice. In: Fiebig HH, Berger DP, editors. Immunodeficient mice in Oncology. Basel: Karger; 1992. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiebig HH, Dengler WA, Roth T. Human tumor xenografts: Predictivity, characterization and discovery of new anticancer agents. In: Fiebig HH, Burger AM, editors. Relevance of tumor models for anticancer drug development. Karger: Basel; 1999. pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman DG, Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Dangers of using "optimal" cutpoints in the evaluation of prognostic factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:829–835. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.11.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockhart DJ, Dong H, Byrne MC, Folletttie MT, Gallo MV, Chee MS, et al. Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1675–1680. doi: 10.1038/nbt1296-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burger AM, Fiebig HH, Stinson SF, Sausville EA. 17-(Allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin activity in human melanoma models. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15:377–387. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alroy J, Goyal V, Skutelsky E. Lectin histochemistry of mammalian endothelium. Histochemistry. 1987;86:603–607. doi: 10.1007/BF00489554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinkerhoff CE. Rutter JL and Benbow U: Interstitial collagenases as markers of tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4823–4830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podgorski I, Sloane BF. Cathepsin B and its role(s) in cancer progression. Biochem Soc. 2003;70:263–276. doi: 10.1042/bss0700263. Symp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordes N, Park CC. β integrin as a molecular therapeutic target. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83:753–760. doi: 10.1080/09553000701639694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper CR, Chay CH, Gendernalik JD, Lee HL, Bhatia J, Taichman RS, McCauley LK, Keller ET, Pienta KJ. Stromal factors involved in prostate carcinoma metastasis to bone. Cancer. 2003;97:739–747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z, Bao SD. Roles of main pro- and anti-angiogenic factors in tumor angiogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:463–470. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asano M, Yukita A, Suzuki H. Wide spectrum of antitumor activity of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to human vascular endothelial growth factor. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1999;90:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanai T, Konno H, Tanaka T, Baba M, Matsumoto K, Nakamura S, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-metastatic effects of human-vascular-endothelial-growth-factor-neutralizing antibody on human colon and gastric carcinoma xenotransplanted orthotopically into nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:933–936. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980911)77:6<933::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eijan AM, Sandes E, Puricelli L, Bai De Kier JE, Casabe AR. Cathepsin B levels in urine from bladder cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:1395–1399. doi: 10.3892/or.7.6.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha AAR, Wilson Mj, Gleason DF, Reddy PK, Sameni M, Sloane BF. Immunohistochemical localization of cathepsin B in neoplastic human prostate. Prostate. 1995;26:171–178. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990260402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujise N, Nanashim A, Taniguchi Y, Matsuo S, Hatano K, Matsumoto Y, et al. Prognostic impact of cathepsin B and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lung adenocarcinomas by immunohistochemical study. Lung Cancer. 2000;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruszewski WJ, Rzepko R, Wojtacki J, Skokowski J, Kopacz A, Jaskiewicz K, et al. Overexpression of cathepsin B correlates with angiogenesis in colon adenocarcinoma. Neoplasma. 2004;51:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lah TT, Cercek M, Blejec A, Kos J, Gorodetsky E, Somers R, et al. Cathepsin B, a prognostic indicator in lymph node-negative breast carcinoma patients: comparison with cathepsin D , cathepsin L,and other clinical indicators. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strojan P, Budihna M, Smid L, Vrhovec I, Skrk J. Prognostic significance of cysteine proteinases cathepsins B and L and their endogenous inhibitors stefins A and B in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1052–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marten K, Bremer C, Khazaie K, Sameni M, Sloane B, Tung CH, et al. Detection of dysplastic intestinal adenomas using enzyme-sensing molecular beacons in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:406–414. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubowchik GM, Firestone RA, Padilla L, Willner D, Hofstead SJ, Masure K, et al. Cathepsin B-Iabile dipeptide linkers for lysosomal release of doxorubicin from internalizing immunoconjugates: model studies of enzymatic drug release and antigen-specific in vitro anticancer activity. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:855–869. doi: 10.1021/bc025536j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toki BE, Cerveny CG, Wahl AF, Senter PD. Protease-mediated fragmentation of p-amidobenzyl ethers: a new strategy for the activation of anticancer prodrugs. J Org Chem. 2002;67:1866–1872. doi: 10.1021/jo016187+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satchi R, Connors TA, Duncan R. PDEPT: polymer-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. I. HPMA copolymer-cathepsin B and PK1 as a model combination. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1070–1076. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granovsky-Grisaru S, Zaidoun S, Grisaru D, Yekel Y, Prus D, Beller U, et al. The pattern of Protease Activated Receptor 1 (PAR1) expression in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:802–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X, Hunt JL, Landsittel DP, Muller S, Adler-Storthz K, Ferris RL, et al. Correlation of protease-activated receptor-1 with differentiation markers in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and its implication in lymph node metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8451–8459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, Gilcrease MZ, Henderson Y, Yuan XH, Clayman GL, Chen Z. Expression of protease-activated receptor 1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2001;169:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00504-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biore A, Covic L, Agarwal A, Jacques S, Sherifi S, Kuliopulos A. PAR1 is a matrix metalloprotease-1 receptor that promotes invasion and tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2005;120:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pei D. Matrix metalloproteinases target protease-activated receptors on the tumor cell surface. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:207–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray GI, Duncan ME, O’Neil P, McKAy JA, Melvin WT, Fothergill JE. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 is associated with poor prognosis in oesophageal cancer. J Pathol. 1998;185:256–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199807)185:3<256::AID-PATH115>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu ZD, Li JY, Li M, Gu J, Shi XT, Ke Y, Chen KN. Matrix metalloproteinases expression correlates with survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1835–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanamori Y, Matsushima M, Minaguchi T, Kobayashi K, Sagae S, Kudo R, et al. Correlation between expression of the Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 Gene in Ovarian Cancers and an Insertion/Deletion Polymorphism in Its Promotor Region. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4225–4227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito T, Ito M, Shiozawa J, Naito S, Kanematsu T, Sekine I. Expression of the MMP-1 in human pancreatic carcinoma: relationshiop with prognostic factor. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pritchard SC, Nicolson MC, Lioret C, McKay JA, Ross VG, Kerr KM, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, 9 and their tissue inhibitors in stage II non-small cell lung cancer: implications for MMP inhibition therapy. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schütz A, Schneidenbach D, Aust G, Tannapfel A, Steinert M, Wittekind C. Differential expression and activity status of MMP-1, MMP-2 and MMP-9 in tumor and stromal cells of squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:179–184. doi: 10.1159/000064034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liebert M, Washington R, Stein J, Wedemeyer G, Grossman HB. Expression of the VLA beta 1 integrin family in bladder Cancer. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:1016–1022. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller-Klingspor V, Hefler L, Obermair A, Kaider A, Breitenecker G, Leodolte S. Prognostic value of beta 1-integrin (=CD29) in serous adenocarcinomas of the ovary. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:2185–2188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloch W, Forsberg E, Lentini S, Brakebusch C, Martin K, Krell HW. Beta 1 integrin is essential for teratoma growth and angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:265–278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Podar K, Tai YT, Lin BK, Narsimhan RP, Kijima T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced migration of multiple myeloma cells is associated with beta 1 integrin – and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent PKC alpha activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7875–7881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berry MG, Gui GP, Wells CA, Carpenter R. Integrin expression and survival in human breast Cancer. EurJ Surg Oncol. 2004;30:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bottger TC, Maschek H, Lobo M, Gottwohl RG, Brenner W, Junginger T. Prognostic value of immunohistochemical expression of beta-1 integrin in pancreatic carcinoma. Oncology. 1999;56:308–313. doi: 10.1159/000011984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]