Abstract

The majority of people who attempt to quit smoking without some assistance relapse within the first couple of weeks, indicating the increased vulnerability during the early withdrawal period. The habenula, which projects via the fasciculus retroflexus to the interpeduncular nucleus, plays an important role in the withdrawal syndrome. Particularly the α2, α5, and β4 subunits of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor have critical roles in mediating the somatic manifestations of withdrawal. Furthermore, withdrawal from nicotine induces a hypodopaminergic state, but there is a relative increase in the sensitivity to phasic dopamine release that is caused by nicotine. Therefore, acute nicotine re-exposure causes a phasic DA response that more potently reinforces relapse to smoking during the withdrawal period.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits that are highly expressed in the medial habenula and/or interpeduncular nucleus play a critical role in nicotine withdrawal.

Long-term use of an addictive drug produces physiological and neurological adaptations that are often accompanied by physical and/or psychological dependence. On discontinuation of the drug, a set of withdrawal symptoms occur for a period of time. Depending on the half-life of the drug in the body, withdrawal may begin within hours of discontinuing use and last for days, weeks, or longer depending on the drug and overall circumstances. The severity of the symptoms depends on the particular individual, the drug in question (e.g., cocaine, benzodiazepines, or nicotine), the route of administration (e.g., intravenous, oral, or inhaled), the doses used, and the abruptness of quitting. Whereas most cigarette smokers quit their nicotine addiction without medical assistance, the physical dependence that may develop to other addictive drugs, such as benzodiazepine and alcohol, can produce life threatening withdrawal symptoms when these drugs are abruptly stopped. In this chapter, we will focus on withdrawal from nicotine, which is the main addictive component found in tobacco (Marti et al. 2011).

In developed countries, tobacco use is estimated to be the largest single cause of premature death, and about one-half of those who smoke from adolescence throughout life will die from smoking-related complications (WHO 1997; Doll et al. 2004). About one-third of the world's adult population smokes tobacco, and in less developed countries, tobacco use is on the rise (Peto et al. 1996; Mathers and Loncar 2006; Benowitz 2008). Thus, it is one of the few causes of mortality that is increasing worldwide (Mathers and Loncar 2006). Tobacco is projected to be responsible for 10% of all deaths globally by 2015 (Mathers and Loncar 2006; Benowitz 2008).

In the U.S., about 45 million people smoke, 70% express a desire to quit, and nearly 50% try to quit each year (Kenford and Fiore 2004; Benowitz 2010). After one year's time, however, only about 3% to 7% of those who attempt to quit on their own are still tobacco free (Kenford and Fiore 2004; MMWR 2005). There are many behavioral and environmental issues that contribute to the low success rate (Dani and Harris 2005; Dani et al. 2009; Benowitz 2010; De Biasi and Dani 2011). An important motivation to relapse is the withdrawal syndrome that arises from chronic nicotine use. Consequently, the majority of people who attempt unaided to quit smoking relapse within the first 2 wk (Ward et al. 1997; Shiffman 2006), indicating that the early withdrawal period is a critical time for relapse and, potentially, for intervention.

THE DOPAMINE SYSTEMS

The mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) system has received the most attention for its role in reinforcing rewarding behaviors, including those behaviors that contribute to addictions (Wise 2009; Ikemoto 2010; Schultz 2010; De Biasi and Dani 2011). The midbrain DA neurons from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) project extensively to cortical sites, and the innervation to the prefrontal cortex has received much attention for its role in addiction (Hyman et al. 2006; Koob and Volkow 2010). The most dense DA innervation of the brain, however, is into the striatum. The DA neurons in the substantia nigra compacta (SNc) and the VTA generally project topologically to the striatum, which may be divided into the dorsal and ventral portions (Björklund 1984; Wilson 1998; Parent et al. 2000; Zhou et al. 2002). The dorsal striatum (neostriatum) comprises the caudate nucleus and the putamen, and the ventral striatum includes the ventral conjunction of the caudate and putamen, portions of the olfactory tubercle, and the nucleus accumbens (NAc). The phylogenetically older ventral striatum along with the amygdala and hippocampus contribute to the mesolimbic DA system, and the projection from the VTA to the NAc has a major role particularly during the initiation of addiction.

Besides having a role in behavior to achieve natural hedonic/pleasurable responses to reinforcers and drugs, the VTA is now recognized to also participate in the responses to punishment, aversion, or lack of expected reward (Schultz 1998b; Ungless et al. 2004; Schultz 2007a; Brischoux et al. 2009; Jhou et al. 2009a; De Biasi and Dani 2011). Such a dual role in reward processing is defined by inputs received from multiple structures in the cortex, basal forebrain, and brainstem (Nauta et al. 1978; Phillipson 1979; Wallace et al. 1989, 1992; Geisler et al. 2007, 2008; Omelchenko and Sesack 2010; Balcita-Pedicino et al. 2011). Those inputs translate into activation of DA neurons whenever a behaviorally salient stimulus, such as one predicting reward, is encountered (Schultz 1998a). Inhibition occurs in cases in which the expected reward is omitted, or an aversive stimulus is delivered (Ungless et al. 2004; Schultz 2007a,b). Major GABA inhibitory inputs to the VTA are provided by feedback projections from the NAc and the ventral pallidum (Usuda et al. 1998; Zahm 2000; Geisler and Zahm 2005). Additional inhibitory afferents arise from the hypothalamus, diagonal band, bed nucleus, lateral septum, periaqueductal gray, pedunculopontine/laterodorsal tegmentum, as well as parabrachial and raphe nuclei (Geisler and Zahm 2005). Another major ascending source of GABAergic inhibition that has been characterized only in recent years is the mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) (Jhou et al. 2009a; Kaufling et al. 2009; Hong et al. 2011; Lecca et al. 2011). Located at the “tail” of the VTA, the RMTg (Perrotti et al. 2005; Olson and Nestler 2007; Geisler et al. 2008; Jhou et al. 2009b; Kaufling et al. 2009; Sesack and Grace 2010) participates in the processing of both aversive and appetitive stimuli (Jhou et al. 2009a). Opposite to the VTA, RMTg neurons are activated by noxious stimuli and inhibited by rewarding stimuli (Jhou et al. 2009a; Hong et al. 2011) so that in the presence of aversive stimuli, RMTg activation leads to inhibition of DA cell activity (Grace and Bunney 1979; Ungless et al. 2004; Jhou et al. 2009a).

The RMTg receives afferents from many forebrain and brainstem structures (Jhou et al. 2009b), but the excitatory glutamatergic projections received from the lateral nucleus of the habenula (LHb) are of particular relevance. The LHb, together with the medial habenula (MHb) forms the habenula complex, an epithalamic structure located by the third ventricle. Although adjacent, LHb and MHb have very different anatomical connections and transcriptional profiles (Klemm 2004). The habenula participates in the processing of fear, anxiety, depression, and stress and, in general, seems to be activated by negative emotional states (Ullsperger and von Cramon 2003; Geisler and Trimble 2008; Matsumoto and Hikosaka 2009; Ikemoto 2010; De Biasi and Dani 2011; Winter et al. 2011). Projections from the habenula are bundled in the fasciculus retroflexus, which is divided into a core region and an outer region. The core of the fasciculus retroflexus originates in the MHb and ends at the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) whereas the outer region originates in the LHb and ends at the RMTg. Through its connections with the RMTg, the LHb exerts potent influence on DAergic activity and reward prediction (Herkenham and Nauta 1979; Araki et al. 1988; Ji and Shepard 2007; Matsumoto and Hikosaka 2007; Hikosaka et al. 2008; Jhou et al. 2009b; Kaufling et al. 2009). The activities of the LHb and the VTA/SNc are anticorrelated so that, opposite to the VTA, LHb activity increases when an expected reward is not delivered (signaling a negative prediction error), and decreases when a reward is delivered unexpectedly (signaling a positive prediction error) (Matsumoto and Hikosaka 2007). The MHb sends projections to the LHb (Kim et al. 2005), but it is currently unknown whether the MHb contributes directly to the regulation of monoamine transmission. Because most projections from the MHb reach the IPN (Klemm 2004), which in turn sends projections to the VTA (Groenewegen et al. 1986; Montone et al. 1988; Klemm 2004), the MHb most likely influences DAergic activity through its connections with the IPN. Data from the literature support an involvement of the MHb/IPN axis with brain reward areas. For example, electrical stimulation of the MHb and the fasciculus retroflexus, the primary efferent pathway of the MHb, produces rewarding effects (Sutherland and Nakajima 1981).

Nicotine Modulation of Dopamine Signaling

Acute nicotine exposure both activates and desensitizes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in a subtype-dependent manner throughout the brain (Dani et al. 2000; Mansvelder and McGehee 2002; Wooltorton et al. 2003; Pidoplichko et al. 2004). At the midbrain DA centers, nicotine acts mainly through nicotinic receptors containing the α4 and β2 subunits, often in combination with the α6 subunit (Picciotto et al. 1998; Tapper et al. 2004; Mameli-Engvall et al. 2006; Pons et al. 2008; Brunzell et al. 2010; Drenan et al. 2010), and induces increased firing of DA neurons that can last for significant periods of time because long-term synaptic potential is induced at some excitatory glutamate synapses arriving particularly from the cortex (Mansvelder and McGehee 2000; Mansvelder et al. 2002) and from the peduncular pontine and lateral dorsal tegmentum (Pidoplichko et al. 2004). On the arrival of nicotine in the midbrain, a majority of midbrain DA neurons increase their firing rates and the firing patterns change (Grenhoff et al. 1986; Mameli-Engvall et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2009b; Zhao-Shea et al. 2011). Nicotine induces an increased firing rate that in general expresses more phasic bursts, and the bursts of firing become longer, containing more individual spikes. This increase in phasic burst firing has profound and varying consequences on DA release in target areas.

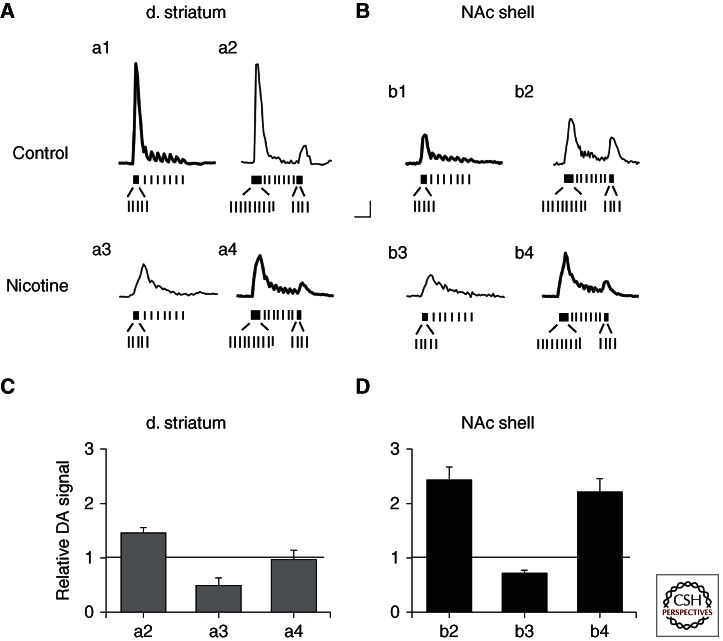

Studies using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in rodents have shown that DA release varies within regions, subregions, and local environments of the brain, suggesting that controls intrinsic and extrinsic to the DA fibers and terminals regulate release (Zachek et al. 2010). This property has been most extensively studied within the dorsal and ventral striatum. DA axon terminals in the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell of the ventral striatum release DA differently, and the DA release evoked by various afferent action potential patterns is modulated differently (Cragg et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2009a,b). For example, as indicated by the inset vertical lines of Figure 1A,B, two stimulus trains were applied to evoke DA release in brain slices from either the dorsal lateral striatum (d. striatum) or the NAc shell (Zhang et al. 2009b). The two stimulus trains are modeled after in vivo measurements of firing under control conditions (a brief burst and simple spikes, e.g., Fig. 1Aa1) and of firing after administration of nicotine (longer and more frequent bursts, e.g., Fig. 1Aa2). These stimulus trains were applied to brain slices bathed in control solutions or in a solution containing a biologically reasonable concentration of nicotine (0.1 µm). In the dorsal striatum (Fig. 1A), the two stimulus trains evoke comparable amounts of DA release, indicated by the area under the curves of the two traces (Fig. 1C). In the NAc shell (Fig. 1B), the stimulation with more and longer phasic bursts induced a greater facilitation of DA release than the other stimulus train (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Measurements of DA release by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry from brain slices. The burst firing by DA neurons was measured in vivo and then was used to construct stimulus trains to evoke DA release in the presence and absence of nicotine (0.1 µm). The stimulus trains were applied to brain slices containing either (A) the dorsolateral striatum (d. striatum) or (B) the nucleus accumbens shell (NAc shell). The DA traces shown in bold are those expected biologically in the absence (a1, b1) or in the presence (a4, b4) of nicotine. Patterned stimulus trains based on the in vivo DA-unit recordings are shown below the evoked DA release in the absence (control) or presence of nicotine bathing the slices. Scale bar, 0.1 µm, 1 sec. The relative DA signal (area-under-curve) is normalized to a1 (horizontal line) in C, the dorsal striatum and to b1 (horizontal line) in D, the NAc shell. The relative (i.e., area under the curve) DA signal was unchanged by nicotine in the dorsal striatum (a4 relative to a1) but was increased in the NAc shell (b4 relative to b1) with p < 0.01. (Modified and adapted from Zhang et al. 2009b.)

These results indicate that the probability of DA release is greater in the dorsal striatum. Thus, there is less potential for facilitation of release by a long burst. Conversely, the NAc shell has a lower basal probability of release than the dorsolateral striatum (Cragg 2003; Rice and Cragg 2004; Zhang and Sulzer 2004; Zhang et al. 2009a,b). Therefore, phasic burst activity into the NAc shell causes more facilitation of DA release.

Acutely administered nicotine, while acting in the midbrain to increase DA neuron firing, acts in the striatal target areas to decrease DA release evoked by single tonic action potentials arriving at the presynaptic terminals. The amount of DA release evoked by identical low frequency, tonic afferent activity is lower in both the dorsal striatum and NAc after nicotine administration as indicated by Figures 1Ca3 and 1Db3 (Zhou et al. 2001; Rice and Cragg 2004; Zhang et al. 2004). In the dorsal striatum, a short burst or a single pulse along the DA fibers produces less DA release in the presence of nicotine (Fig. 1Aa3) than it does in the absence of nicotine (Fig. 1Aa1). If we consider that nicotine increases the burst firing from midbrain DA neurons, then in the nicotine case, we should compare DA release with a stimulus train containing more and longer bursts (Fig. 1Aa4). When you compare the area under the curve, which is the overall DA signal, in the control case (Fig. 1Aa1) to the area under the curve in the nicotine administration case (Fig. 1Aa4) they are the same in the dorsalateral striatum (Fig. 1Ca4). Likewise in the dorsalateral striatum, the overall DA signal, as measured by microdialysis, is not dramatically increased during the first administration of nicotine to a rat (Zhang et al. 2009b). If the same comparison is made in the NAc shell, the DA signal in the control (Fig. 1Bb1) is considerably smaller than the DA signal in the presence of nicotine (Fig. 1Bb4). As measured by microdialysis, the first injection of nicotine causes a significant increase in the DA concentration in the NAc shell (Zhang et al. 2009b), and this result is consistent with the nicotine-induced increase in DA release (Fig. 1Db4).

Because nicotine decreases tonic DA release much more effectively than release evoked by phasic bursts, nicotine stretches the range of mesostriatal/mesolimbic DA signaling. The low frequency tonic signals are diminished whereas phasic-burst signals (like those induced in the midbrain by nicotine) are favored even more than usual when nicotine is present at the target area (Rice and Cragg 2004; Dani and Harris 2005; Kumari and Postma 2005; Benowitz 2008; Zhang et al. 2009a,b). Thus, the relationship between DA neuron firing patterns and DA release varies depending on the local area of interest (Garris and Wightman 1994; Wu et al. 2002; Cragg 2003; Montague et al. 2004; Zhang and Sulzer 2004). This variability arises because DA neurons in the midbrain do not have identical properties, and they project, generally, in a topological manner to distant targets. Even when the DA neurons have similar firing trains, different frequency-dependent DA release occurs depending on the region where they project (Cragg 2003; Exley et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009a,b). Phasic burst firing by DA neurons and the consequent downstream phasic DA signals produced in the targets are vital for processing reward-related information associated with the drug-use behavior. This process is an important step for the initial phase of nicotine addiction. Like other addictive drugs, nicotine initially increases the basal DA concentration in the NAc shell as measured by microdialysis (Pontieri et al. 1996; Di Chiara 1999; Zhang et al. 2009b). As measured by microdialysis, the elevated dopamine in the NAc shell is considered an identifying functional characteristic of addictive drugs.

Adaptations in Dopamine Signaling on Nicotine Withdrawal

As well as mediating aspects of reward and behavioral reinforcement, alterations in DA signaling also mediate aspects of nicotine withdrawal (Corrigall et al. 1994; Dani and Heinemann 1996; De Biasi and Dani 2011; Zhang et al. 2012). Withdrawal from various addictive drugs results in a decrease in basal DA that is thought to motivate drug seeking and taking (Weiss et al. 1996; Shen 2003). Likewise, withdrawal from chronic nicotine use also induces a hypodopaminergic state (Epping-Jordan et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 2012). This deficiency in basal DA alters brain reward function and may motivate drug seeking to reverse the nicotine-induced DA deficiency (Epping-Jordan et al. 1998). Consistent with these kinds of data, the majority of people who attempt to quit smoking unaided by medical supports relapse within the first 2 wk (Ward et al. 1997; Shiffman 2006), suggesting that the early period following nicotine withdrawal is a critical time.

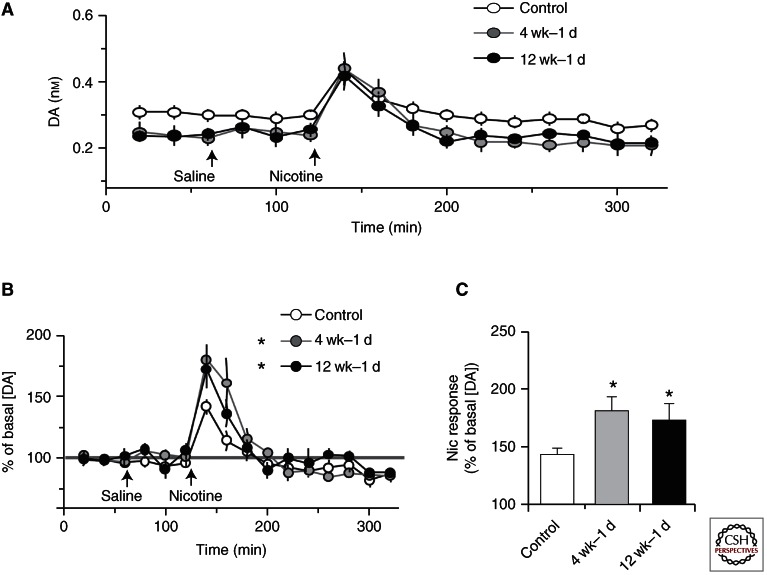

When nicotine was self-administered by mice in their home cage drinking water for 4 or 12 wk followed by 1 d of withdrawal, the mean basal DA concentration measured by microdialysis in the NAc was significantly and comparably lower after both treatments compared with control (Fig. 2A). Acute administration of nicotine (1 mg/kg, i.p., nicotine upward arrow, Fig. 2A) increased the absolute DA concentrations to similar levels for both control mice and for those in withdrawal. Because the nicotine-treated mice had lower baseline DA concentrations than the control mice, the baselines were normalized to compare the relative amplitudes of the nicotine-induced DA concentration changes (Fig. 2B). Both the 4-wk and 12-wk withdrawal groups showed a significantly higher relative nicotine-induced DA response compared with the control mice (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Measurements of DA concentrations by in vivo microdialysis in freely moving mice. Nicotine was self-administrated via the drinking water for 4 or 12 wk followed by 1 d of withdrawal. (A) Dialysate DA concentrations at baseline and after an i.p. injection of saline and nicotine (1 mg/kg) following 1 d of withdrawal from 4 or 12 wk (wk) of chronic nicotine. Nicotine withdrawal decreased basal DA levels compared with the control. (B) Normalization of the dialysate DA signals revealed that the response to acute nicotine was enhanced in both withdrawal groups compared with the control. (C) The peak nicotine-induced DA responses are re-plotted as bar graphs showing that the nicotine evoked peak was higher in both withdrawal groups than in the control. *p < 0.05 by t-test. (Modified and adapted from Zhang et al. 2012.)

To understand the changes in DA signaling caused by withdrawal, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry measurements were made in brain slices cut from the NAc 1 d into withdrawal. It was found that during nicotine withdrawal both tonic and phasic DA release was decreased. The basal DA concentration and tonic DA signals, however, were disproportionately lower than the phasic DA signals. Therefore, the phasic/tonic DA signaling ratio was increased during the withdrawal period. Consistent with the microdialysis results, the DA signal produced by acute nicotine re-exposure during withdrawal produces a DA response that may strongly reinforce relapse to drug use (i.e., smoking). After chronic nicotine, the stronger inhibition of tonic DA release enhances the contrast between tonic and phasic DA signaling. It also switches the pattern of DA release so that it is more highly dependent on the number of spikes within a burst. That change increases the dependence of NAc DA release on bursts. Therefore, during the withdrawal period, phasic DA neuron activity of the kind induced by nicotine (Zhang et al. 2009b; Exley et al. 2011) re-exposure induces DA signals that may make abstinent smokers more vulnerable to the reinforcing influence of nicotine (De Biasi and Dani 2011; Zhang et al. 2012).

ROLE OF HABENULA AND IPN IN NICOTINE WITHDRAWAL

Withdrawal manifests as a collection of affective and somatic symptoms that emerge a few hours after nicotine abstinence. The seven major symptoms of nicotine withdrawal appearing in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000; Hughes 2007) include irritability/anger/frustration, anxiety, depression/negative affect, concentration problems, impatience, insomnia, and restlessness. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms typically peak within the first week of abstinence and taper off in the following 3–4 wk (Hughes et al. 1991; Hughes 2007). However, the duration of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome has been reported to be as short as 10 d (Shiffman 2006), or last more than a month (Gilbert et al. 1999; Gilbert et al. 2002). The severity of nicotine withdrawal symptoms varies among individuals, but a severe abstinence syndrome predicts increased risk of relapse (West et al. 1989; Piasecki et al. 2003a,b,c; al’Absi et al. 2004). Powerful cravings also accompany withdrawal, which may be precipitated by cues such as the sight of a cigarette or a situation/place associated with the act of smoking (Shiffman et al. 2002). The onset of negative affective symptoms, such as dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability and, to a lesser extent, the somatic manifestations of withdrawal, provide negative reinforcement that perpetuates addiction (Koob and Le Moal 2001, 2005; Allen et al. 2008; Koob and Volkow 2010; Piper et al. 2011). Continued cigarette use or relapse is therefore driven not only by the pursuit of hedonically positive effects but also the avoidance of negative states associated with withdrawal.

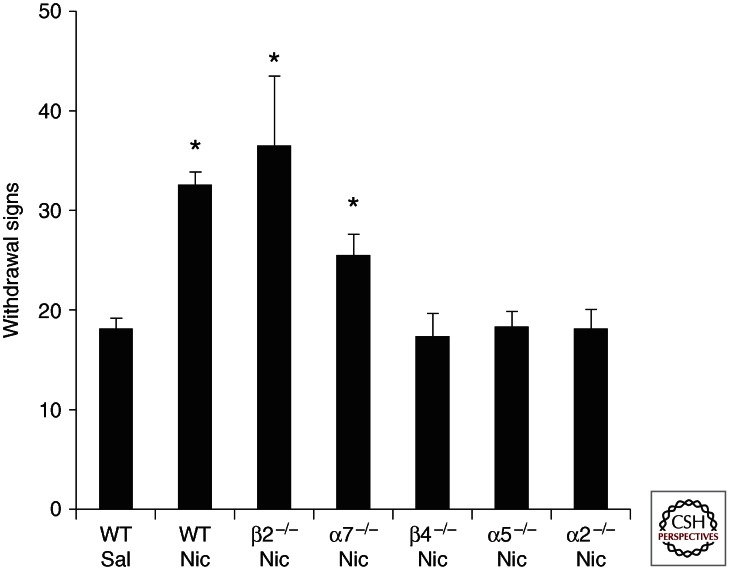

Given the involvement of the LHb in the processing of negative emotional states, it is tempting to speculate that the nucleus might also be involved in the mechanisms of nicotine withdrawal, especially for symptoms like anxiety, depression, and negative affect. Research in both humans and animal models will be required to test this hypothesis. The putative involvement of the LHb in the nicotine abstinence syndrome contrasts with compelling data on the influence of the MHb on the somatic manifestations of withdrawal (Salas et al. 2004, 2007, 2009). Mice display both somatic (e.g., shaking, paw tremors, or scratching) and affective signs of nicotine withdrawal (e.g., increased anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze or increased threshold for intracranial self-stimulation) (De Biasi and Salas 2008). A survey of various nAChR mutant mice in which withdrawal was precipitated by the injection of the nAChR antagonist, mecamylamine (MEC), has revealed the prominent influence of three nAChR subunits (Fig. 3) (Salas et al. 2004, 2007, 2009). Absence of α2 or α5 or β4 abolishes the somatic signs of withdrawal (Salas et al. 2004, 2007, 2009), lack of α7 attenuates withdrawal symptoms (Salas et al. 2007), but physical signs of dependency are still observed in the absence of β2 (Salas et al. 2004; Besson et al. 2006). Both α5 and β4 null mice also manifest reduced anxiety-related behaviors (Salas et al. 2003; Gangitano et al. 2009), in contrast with β2 null mice, which show normal anxiety-like responses (Maskos et al. 2005). Considering the role of anxiety and stress in nicotine withdrawal and relapse, the latter result points to another potential influence of α5- and β4-containing nAChRs (De Biasi and Salas 2008).

Figure 3.

Lack of β4, α5, or α2 nAChR subunits protect against nicotine withdrawal-induced somatic signs. nAChR null mice and their wild type littermates were treated chronically with nicotine (24 mg/kg/d free base) or saline using a mini-osmotic pump for 2 wk. On day 14, mice received a 3 mg/kg injection of the nonselective nicotinic antagonist, mecamylamine. Somatic signs, which include scratching, shaking, chewing, grooming, ptosis, head nodding, and jumping, were measured for 20 min. Mecamylamine injection produced an increase in somatic signs in wild-type, β2 null, and α7 null mice treated with nicotine. Similar increases were not observed in the β4, α5, or α2 null mice suggesting that nAChRs that contain these subunits play a role in the modulation of nicotine withdrawal signs. *p < 0.05. (Modified and adapted from Salas et al. 2004, 2007, 2009.)

In the mouse, the α5, α2, and β4 nAChR subunits are expressed at high levels in MHb and/or IPN (Grady et al. 2009; De Biasi and Dani 2011), whereas no mRNA encoding for those nAChR subunits can be detected in the LHb. The definitive role of the MHb/IPN axis in the somatic manifestations of nicotine abstinence was established when MEC was microinjected into the MHb and IPN of mice chronically treated with nicotine. MEC microinjection in those two brain areas—but not VTA, hippocampus, or cortex, was sufficient to precipitate nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Salas et al. 2009). An interesting question is whether the MHb and IPN influence only the mechanisms of nicotine withdrawal or whether they have a more global influence on other drugs of abuse.

A recent report suggests that α5-containing nAChRs in the MHb/IPN axis are also key to the control of the amounts of nicotine self-administered. Nicotine follows an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve (Picciotto 2003; De Biasi and Dani 2011), and smokers titrate their nicotine intake to experience the rewarding while avoiding the aversive effects produced by high nicotine doses (Benowitz and Jacob 2001; Hutchison and Riley 2008; Dani et al. 2009). In the absence of α5, mice continue to self-administer nicotine at doses that normally elicit aversion in wild-type animals (Fowler et al. 2011). However, re-expression of the nAChR subunit in the MHb or the IPN is sufficient to bring nicotine self-administration back to wild-type levels (Fowler et al. 2011). These data suggest a role for both LHb and MHb in the processing of aversive stimuli, including those associated with high nicotine doses.

The α5 and β4 subunit genes belong to a cluster that also encodes the α3 nAChR subunit. This gene cluster, located in mouse chromosome 9 (syntenic to human chromosome 15q25), has acquired notoriety after a number of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) linked single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) within CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 to tobacco use, lung cancer, peripheral disease, and alcohol abuse (Amos et al. 2008; Berrettini et al. 2008; Bierut et al. 2008; Thorgeirsson et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2011). The nonsynonymous SNP rs16969968 in CHRNA5 correlates with nicotine dependency risk, heavy smoking, and the pleasurable sensation produced by a cigarette (Saccone et al. 2007; Berrettini et al. 2008; Bierut et al. 2008; Thorgeirsson et al. 2008). This SNP leads to an amino acid substitution in the second intracellular loop of the α5 subunit, which results in lower Ca2+ permeability and increased desensitization in nAChRs with certain subunit compositions (Kuryatov et al. 2011). Because the α5 nAChR subunit influences the aversive effects of nicotine and drives its consumption, it is tempting to speculate that people with SNP rs16969968 smoke more and become addicted at a younger age because of hypofunctional α5-containing nAChRs. The presence of fewer aversive effects (especially at higher nicotine doses) during the initial exposure to nicotine would promote the hedonic drive and facilitate the transition from use to abuse and dependency. New mouse models examining the role of nAChR gene variants will help investigators explore the role of gene polymorphisms in nicotine addiction and will provide insight into cessation therapies tailored for specific subpopulations of smokers.

CONCLUSIONS

Animal studies and human genetic data point to the MHb/IPN axis and the nAChRs expressed therein as critical mediators of the mechanisms of nicotine withdrawal. As a whole, the habenula complex emerges as part of a circuitry that may control the negative emotional states driven by abstinence or aversive drug concentrations. In the next phase of research, new animal models and more selective nAChR antagonists will be used to understand the underlying mechanisms of tobacco addiction and withdrawal, providing targets for drugs aimed at aiding smoking cessation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA017173, DA029157, and CA148127 to M.D.B., DA09411 and NS21229 to J.A.D.) and by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (M.D.B and J.A.D). We also acknowledge the joint participation by Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation, through its direct engagement in the continuous active conduct of medical research in conjunction with Baylor College of Medicine and the “Genomic, Neural, Preclinical Analysis for Smoking Cessation” project for the Cancer Research Program.

Footnotes

Editors: R. Christopher Pierce and Paul J. Kenny

Additional Perspectives on Addiction available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL, Wittmers LE 2004. Prospective examination of effects of smoking abstinence on cortisol and withdrawal symptoms as predictors of early smoking relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend 73: 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SS, Bade T, Hatsukami D, Center B 2008. Craving, withdrawal, and smoking urges on days immediately prior to smoking relapse. Nicotine Tob Res 10: 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual-text revision (DSM-IV-TR). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, Dong Q, Zhang Q, Gu X, Vijayakrishnan J, et al. 2008. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet 40: 616–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki M, McGeer PL, Kimura H 1988. The efferent projections of the rat lateral habenular nucleus revealed by the PHA-L anterograde tracing method. Brain Res 441: 319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcita-Pedicino JJ, Omelchenko N, Bell R, Sesack SR 2011. The inhibitory influence of the lateral habenula on midbrain dopamine cells: Ultrastructural evidence for indirect mediation via the rostromedial mesopontine tegmental nucleus. J Comp Neurol 519: 1143–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL 2008. Clinical pharmacology of nicotine: Implications for understanding, preventing, and treating tobacco addiction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 83: 531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL 2010. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med 362: 2295–2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Jacob P 3rd 2001. Trans-3′-hydroxycotinine: disposition kinetics, effects and plasma levels during cigarette smoking. Br J Clin Pharmacol 51: 53–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini W, Yuan X, Tozzi F, Song K, Francks C, Chilcoat H, Waterworth D, Muglia P, Mooser V 2008. α5/α3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Mol Psychiatry 13: 368–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson M, David V, Suarez S, Cormier A, Cazala P, Changeux JP, Granon S 2006. Genetic dissociation of two behaviors associated with nicotine addiction: β2 containing nicotinic receptors are involved in nicotine reinforcement but not in withdrawal syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 187: 189–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Stitzel JA, Wang JC, Hinrichs AL, Grucza RA, Xuei X, Saccone NL, Saccone SF, Bertelsen S, Fox L, et al. 2008. Variants in nicotinic receptors and risk for nicotine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 165: 1163–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, Lindvall O 1984. Dopamine-containing systems in the CNS. In Classical transmitters in the CNS, Part I (ed. Björklund A, Hökfelt T), pp. 55–122 Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, Ungless MA 2009. Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 4894–4899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Boschen KE, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM, McIntosh JM 2010. α-conotoxin MII-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell regulate progressive ratio responding maintained by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 665–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wu X, Pande M, Amos CI, Killary AM, Sen S, Frazier ML 2011. Susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1 is not associated with risk of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 40: 872–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL 1994. Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res 653: 278–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg SJ 2003. Variable dopamine release probability and short-term plasticity between functional domains of the primate striatum. J Neurosci 23: 4378–4385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg SJ, Hille CJ, Greenfield SA 2002. Functional domains in dorsal striatum of the nonhuman primate are defined by the dynamic behavior of dopamine. J Neurosci 22: 5705–5712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Harris RA 2005. Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nat Neurosci 8: 1465–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Heinemann S 1996. Molecular and cellular aspects of nicotine abuse. Neuron 16: 905–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Radcliffe KA, Pidoplichko VI 2000. Variations in desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors from hippocampus and midbrain dopamine areas. Eur J Pharmacol 393: 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Kosten TR, Benowitz NL 2009. The pharmacology of nicotine and tobacco. In Principles of addiction medicine (ed. Ries RK, et al. ), pp. 179–191 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi M, Dani JA 2011. Reward, addiction, withdrawal to nicotine. Annu Rev Neurosci 34: 105–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi M, Salas R 2008. Influence of neuronal nicotinic receptors over nicotine addiction and withdrawal. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 917–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G 1999. Drug addiction as dopamine-dependent associative learning disorder. Eur J Pharmacol 375: 13–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I 2004. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 328: 1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Steele AD, McKinney S, Patzlaff NE, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Miwa JM, Lester HA 2010. Cholinergic modulation of locomotion and striatal dopamine release is mediated by α6α4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 30: 9877–9889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epping-Jordan MP, Watkins SS, Koob GF, Markou A 1998. Dramatic decreases in brain reward function during nicotine withdrawal. Nature 393: 76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Clements MA, Hartung H, McIntosh JM, Cragg SJ 2008. α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 2158–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Maubourguet N, David V, Eddine R, Evrard A, Pons S, Marti F, Threlfell S, Cazala P, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP, Maskos U, Cragg SJ, Faure P 2011. Distinct contributions of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit {α}4 and subunit {α}6 to the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 7577–7582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CD, Lu Q, Johnson PM, Marks MJ, Kenny PJ 2011. Habenular α5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature 471: 597–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangitano D, Salas R, Teng Y, Perez E, De Biasi M 2009. Progesterone modulation of α5 nAChR subunits influences anxiety-related behavior during estrus cycle. Genes Brain Behav 8: 398–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA, Wightman RM 1994. Different kinetics govern dopaminergic transmission in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and striatum: An in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci 14: 442–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Trimble M 2008. The lateral habenula: No longer neglected. CNS Spectr 13: 484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Zahm DS 2005. Afferents of the ventral tegmental area in the rat-anatomical substratum for integrative functions. J Comp Neurol 490: 270–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Derst C, Veh RW, Zahm DS 2007. Glutamatergic afferents of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. J Neurosci 27: 5730–5743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Marinelli M, Degarmo B, Becker ML, Freiman AJ, Beales M, Meredith GE, Zahm DS 2008. Prominent activation of brainstem and pallidal afferents of the ventral tegmental area by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 2688–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, McClernon FJ, Rabinovich NE, Dibb WD, Plath LC, Hiyane S, Jensen RA, Meliska CJ, Estes SL, Gehlbach BA 1999. EEG, physiology, and task-related mood fail to resolve across 31 days of smoking abstinence: Relations to depressive traits, nicotine exposure, and dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 7: 427–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, McClernon FJ, Rabinovich NE, Plath LC, Masson CL, Anderson AE, Sly KF 2002. Mood disturbance fails to resolve across 31 days of cigarette abstinence in women. J Consult Clin Psychol 70: 142–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS 1979. Paradoxical GABA excitation of nigral dopaminergic cells: indirect mediation through reticulata inhibitory neurons. Eur J Pharmacol 59: 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Moretti M, Zoli M, Marks MJ, Zanardi A, Pucci L, Clementi F, Gotti C 2009. Rodent habenulo-interpeduncular pathway expresses a large variety of uncommon nAChR subtypes, but only the α3β4* and α3β3β4* subtypes mediate acetylcholine release. J Neurosci 29: 2272–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J, Aston-Jones G, Svensson TH 1986. Nicotinic effects on the firing pattern of midbrain dopamine neurons. Acta Physiol Scand 128: 351–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Ahlenius S, Haber SN, Kowall NW, Nauta WJ 1986. Cytoarchitecture, fiber connections, and some histochemical aspects of the interpeduncular nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 249: 65–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Nauta WJ 1979. Efferent connections of the habenular nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol 187: 19–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O, Bromberg-Martin E, Hong S, Matsumoto M 2008. New insights on the subcortical representation of reward. Curr Opin Neurobiol 18: 203–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Jhou TC, Smith M, Saleem KS, Hikosaka O 2011. Negative reward signals from the lateral habenula to dopamine neurons are mediated by rostromedial tegmental nucleus in primates. J Neurosci 31: 11457–11471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR 2007. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res 9: 315–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Gust SW, Skoog K, Keenan RM, Fenwick JW 1991. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. A replication and extension. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison MA, Riley AL 2008. Adolescent exposure to nicotine alters the aversive effects of cocaine in adult rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol 30: 404–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ 2006. Neural mechanisms of addiction: The role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 29: 565–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S 2010. Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: A neurobiological theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35: 129–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Fields HL, Baxter MG, Saper CB, Holland PC 2009a. The rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), a GABAergic afferent to midbrain dopamine neurons, encodes aversive stimuli and inhibits motor responses. Neuron 61: 786–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Geisler S, Marinelli M, Degarmo BA, Zahm DS 2009b. The mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus: A structure targeted by the lateral habenula that projects to the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and substantia nigra compacta. J Comp Neurol 513: 566–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Shepard PD 2007. Lateral habenula stimulation inhibits rat midbrain dopamine neurons through a GABAA receptor-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci 27: 6923–6930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufling J, Veinante P, Pawlowski SA, Freund-Mercier MJ, Barrot M 2009. Afferents to the GABAergic tail of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. J Comp Neurol 513: 597–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Fiore MC 2004. Promoting tobacco cessation and relapse prevention. Med Clin North Am 88: 1553–1574, xi–xii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, Chang SY 2005. Dendritic morphology, local circuitry, and intrinsic electrophysiology of neurons in the rat medial and lateral habenular nuclei of the epithalamus. J Comp Neurol 483: 236–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm WR 2004. Habenular and interpeduncularis nuclei: Shared components in multiple-function networks. Med Sci Monit 10: RA261–RA273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M 2001. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology 24: 97–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M 2005. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the “dark side” of drug addiction. Nat Neurosci 8: 1442–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND 2010. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 217–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Postma P 2005. Nicotine use in schizophrenia: The self medication hypotheses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29: 1021–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Berrettini W, Lindstrom J 2011. Acetylcholine receptor (AChR) α5 subunit variant associated with risk for nicotine dependence and lung cancer reduces (α4β2) α5 AChR function. Mol Pharmacol 79: 119–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecca S, Melis M, Luchicchi A, Ennas MG, Castelli MP, Muntoni AL, Pistis M 2011. Effects of drugs of abuse on putative rostromedial tegmental neurons, inhibitory afferents to midbrain dopamine cells. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 589–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mameli-Engvall M, Evrard A, Pons S, Maskos U, Svensson TH, Changeux JP, Faure P 2006. Hierarchical control of dopamine neuron-firing patterns by nicotinic receptors. Neuron 50: 911–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, McGehee DS 2000. Long-term potentiation of excitatory inputs to brain reward areas by nicotine. Neuron 27: 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, McGehee DS 2002. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms of nicotine addiction. J Neurobiol 53: 606–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, Keath JR, McGehee DS 2002. Synaptic mechanisms underlie nicotine-induced excitability of brain reward areas. Neuron 33: 905–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti F, Arib O, Morel C, Dufresne V, Maskos U, Corringer PJ, de Beaurepaire R, Faure P 2011. Smoke extracts and nicotine, but not tobacco extracts, potentiate firing and burst activity of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 2244–2257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskos U, Molles BE, Pons S, Besson M, Guiard BP, Guilloux JP, Evrard A, Cazala P, Cormier A, Mameli-Engvall M, et al. 2005. Nicotine reinforcement and cognition restored by targeted expression of nicotinic receptors. Nature 436: 103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D 2006. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3: e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O 2007. Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature 447: 1111–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O 2009. Representation of negative motivational value in the primate lateral habenula. Nature neuroscience 12: 77–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MMWR 2005. State-specific prevalence of cigarette smoking and quitting among adults—United States. MMWR 54: 1124–1127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, McClure SM, Baldwin PR, Phillips PE, Budygin EA, Stuber GD, Kilpatrick MR, Wightman RM 2004. Dynamic gain control of dopamine delivery in freely moving animals. J Neurosci 24: 1754–1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montone KT, Fass B, Hamill GS 1988. Serotonergic and nonserotonergic projections from the rat interpeduncular nucleus to the septum, hippocampal formation and raphe: A combined immunocytochemical and fluorescent retrograde labelling study of neurons in the apical subnucleus. Brain Res Bull 20: 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta WJ, Smith GP, Faull RL, Domesick VB 1978. Efferent connections and nigral afferents of the nucleus accumbens septi in the rat. Neuroscience 3: 385–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson VG, Nestler EJ 2007. Topographical organization of GABAergic neurons within the ventral tegmental area of the rat. Synapse 61: 87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko N, Sesack SR 2010. Periaqueductal gray afferents synapse onto dopamine and GABA neurons in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci Res 88: 981–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A, Sato F, Wu Y, Gauthier J, Levesque M, Parent M 2000. Organization of the basal ganglia: The importance of axonal collateralization. Trends Neurosci 23: S20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Bolanos CA, Choi KH, Russo SJ, Edwards S, Ulery PG, Wallace DL, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Barrot M 2005. δFosB accumulates in a GABAergic cell population in the posterior tail of the ventral tegmental area after psychostimulant treatment. Eur J Neurosci 21: 2817–2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C Jr, Doll R 1996. Mortality from smoking worldwide. Br Med Bull 52: 12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson OT 1979. Afferent projections to the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and interfascicular nucleus: A horseradish peroxidase study in the rat. J Comp Neurol 187: 117–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB 2003a. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: I. Abstinence distress in lapsers and abstainers. J Abnorm Psychol 112: 3–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB 2003b. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: II. Improved tests of withdrawal-relapse relations. J Abnorm Psychol 112: 14–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB 2003c. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: III. Correlates of withdrawal heterogeneity. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 11: 276–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR 2003. Nicotine as a modulator of behavior: Beyond the inverted U. Trends Pharmacol Sci 24: 493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio LM, Pich EM, Fuxe K, Changeux JP 1998. Acetylcholine receptors containing the β2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature 391: 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoplichko VI, Noguchi J, Areola OO, Liang Y, Peterson J, Zhang T, Dani JA 2004. Nicotinic cholinergic synaptic mechanisms in the ventral tegmental area contribute to nicotine addiction. Learn Mem 11: 60–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, Jorenby DE, Baker TB 2011. Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: Relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment. Addiction 106: 418–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, Tolu S, Porcu E, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP, Maskos U, Fratta W 2008. Crucial role of α4 and α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J Neurosci 28: 12318–12327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Orzi F, Di Chiara G 1996. Effects of nicotine on the nucleus accumbens and similarity to those of addictive drugs. Nature 382: 255–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Cragg SJ 2004. Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat Neurosci 7: 583–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone SF, Hinrichs AL, Saccone NL, Chase GA, Konvicka K, Madden PA, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Pomerleau O, et al. 2007. Cholinergic nicotinic receptor genes implicated in a nicotine dependence association study targeting 348 candidate genes with 3713 SNPs. Hum Mol Genet 16: 36–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Orr-Urtreger A, Broide RS, Beaudet A, Paylor R, De Biasi M 2003. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit α5 mediates short-term effects of nicotine in vivo. Mol Pharmacol 63: 1059–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Pieri F, De Biasi M 2004. Decreased signs of nicotine withdrawal in mice null for the β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Neurosci 24: 10035–10039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Main A, Gangitano D, De Biasi M 2007. Decreased withdrawal symptoms but normal tolerance to nicotine in mice null for the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. Neuropharmacology 53: 863–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Sturm R, Boulter J, De Biasi M 2009. Nicotinic receptors in the habenulo-interpeduncular system are necessary for nicotine withdrawal in mice. J Neurosci 29: 3014–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W 1998a. The phasic reward signal of primate dopamine neurons. Adv Pharmacol 42: 686–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W 1998b. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol 80: 1–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W 2007a. Behavioral dopamine signals. Trends Neurosci 30: 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W 2007b. Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu Rev Neurosci 30: 259–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W 2010. Dopamine signals for reward value and risk: Basic and recent data. Behav Brain Funct 6: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Grace AA 2010. Cortico-basal ganglia reward network: Microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 27–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen RY 2003. Ethanol withdrawal reduces the number of spontaneously active ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons in conscious animals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 307: 566–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S 2006. Reflections on smoking relapse research. Drug Alcohol Rev 25: 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Hickcox M, Gnys M 2002. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol 111: 531–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland RJ, Nakajima S 1981. Self-stimulation of the habenular complex in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 95: 781–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Lester HA 2004. Nicotine activation of α4* receptors: Sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science 306: 1029–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, Manolescu A, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Ingason A, et al. 2008. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452: 638–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger M, von Cramon DY 2003. Error monitoring using external feedback: Specific roles of the habenular complex, the reward system, and the cingulate motor area revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 23: 4308–4314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP 2004. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science 303: 2040–2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuda I, Tanaka K, Chiba T 1998. Efferent projections of the nucleus accumbens in the rat with special reference to subdivision of the nucleus: Biotinylated dextran amine study. Brain Res 797: 73–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DM, Magnuson DJ, Gray TS 1989. The amygdalo-brainstem pathway: Selective innervation of dopaminergic, noradrenergic and adrenergic cells in the rat. Neurosci Lett 97: 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DM, Magnuson DJ, Gray TS 1992. Organization of amygdaloid projections to brainstem dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and adrenergic cell groups in the rat. Brain Res Bull 28: 447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, Grucza R, Cruchaga C, Hinrichs AL, Bertelsen S, Budde JP, Fox L, Goldstein E, Reyes O, Saccone N, et al. Genetic variation in the CHRNA5 gene affects mRNA levels and is associated with risk for alcohol dependence. Molec Psychiatry 14: 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward KD, Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Bliss RE, Garvey AJ 1997. Gender differences in the outcome of an unaided smoking cessation attempt. Addict Behav 22: 521–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Parsons LH, Schulteis G, Hyytia P, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF 1996. Ethanol self-administration restores withdrawal-associated deficiencies in accumbal dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine release in dependent rats. J Neurosci 16: 3474–3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M 1989. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychol Med 19: 981–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 1997. Tobacco or health, a global status report, p. 495 World Health Organization, Geneva [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ 2004. Basal ganglia. In The synaptic organization of the brain (ed. Shepherd GM), pp. 361–413 Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Vollmayr B, Djodari-Irani A, Klein J, Sartorius A 2011. Pharmacological inhibition of the lateral habenula improves depressive-like behavior in an animal model of treatment resistant depression. Behav Brain Res 216: 463–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA 2009. Roles for nigrostriatal—not just mesocorticolimbic—dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends Neurosci 32: 517–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooltorton JR, Pidoplichko VI, Broide RS, Dani JA 2003. Differential desensitization and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in midbrain dopamine areas. J Neurosci 23: 3176–3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Reith ME, Walker QD, Kuhn CM, Carroll FI, Garris PA 2002. Concurrent autoreceptor-mediated control of dopamine release and uptake during neurotransmission: An in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci 22: 6272–6281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachek MK, Takmakov P, Park J, Wightman RM, McCarty GS 2010. Simultaneous monitoring of dopamine concentration at spatially different brain locations in vivo. Biosens Bioelectron 25: 1179–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS 2000. An integrative neuroanatomical perspective on some subcortical substrates of adaptive responding with emphasis on the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 24: 85–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Sulzer D 2004. Frequency-dependent modulation of dopamine release by nicotine. Nat Neurosci 7: 581–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhou FM, Dani JA 2004. Cholinergic drugs for Alzheimer's disease enhance in vitro dopamine release. Mol Pharmacol 66: 538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Doyon WM, Clark JJ, Phillips PE, Dani JA 2009a. Controls of tonic and phasic dopamine transmission in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Mol Pharmacol 76: 396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Zhang L, Liang Y, Siapas AG, Zhou FM, Dani JA 2009b. Dopamine signaling differences in the nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum exploited by nicotine. J Neurosci 29: 4035–4043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Dong Y, Doyon WM, Dani JA 2012. Withdrawal from chronic nicotine exposure alters dopamine signaling dynamics in the nucleus accumbens. Biol Psychiatry 71: 184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao-Shea R, Liu L, Soll LG, Improgo MR, Meyers EE, McIntosh JM, Grady SR, Marks MJ, Gardner PD, Tapper AR 2011. Nicotine-mediated activation of dopaminergic neurons in distinct regions of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1021–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Liang Y, Dani JA 2001. Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity regulates dopamine release in the striatum. Nat Neurosci 4: 1224–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Wilson CJ, Dani JA 2002. Cholinergic interneuron characteristics and nicotinic properties in the striatum. J Neurobiol 53: 590–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]