Abstract

Prevalent three-dimensional scaffolds for bone tissue engineering are mineralized collagen–hydroxyapatite (Col/HA) composites. Conventional mineralization techniques are either to coat collagen scaffold surfaces with minerals or to simply mix collagen and mineral nanoparticles together. These conventional in vitro collagen mineralization methods are different from the in vivo bone formation process and often result in scaffolds that are not suitable for bone tissue engineering. In this study, a unique perfusion-flow (i.e., dynamic) in conjunction with a previously described polymer-induced liquid-precursor (PILP) method was used to fabricate a porous Col/HA composite. The dynamic flow emulated the physiological extracellular fluid flow containing the mineralization ions, while the PILP method facilitated the deposition of the HA crystals within the collagen fibrils (i.e., intrafibrillar mineralization). By utilizing a dynamic PILP technique to mimic the in vivo bone formation process, the resultant Col/HA composite has a similar structure and compositions like human trabecular bone. A comparison of the dynamic and static mineralization methods revealed that the novel dynamic technique facilitates more efficient and homogenous mineral deposition throughout the Col/HA composite. The dynamic intrafibrillar mineralization method generated stiff Col/HA composites with excellent surface property for cell attachment and growth. The human mesenchymal stem cells cultured on the Col/HA composites quickly remodeled the scaffolds and resulted in constructs with an extensive cell-derived extracellular matrix network.

Introduction

Scaffold design plays a pivotal role in tissue engineering. An effective scaffold should provide an ideal microenvironment to promote cell and tissue growth. At a minimum, a scaffold should exhibit adequate mechanical stability to withstand cell contractile forces, high porosity with interconnected pores to facilitate nutrient delivery and remove metabolic waste, material biocompatibility to promote tissue formation and integration, and an appropriate rate of biodegradability for new tissue regeneration.1–6

Type I collagen is a popular choice for scaffolding material in the regenerative medicine and tissue engineering fields due to its ubiquity, biodegradability, and excellent biocompatibility properties.7 While the biomaterial properties of collagen offer many advantages for a scaffold design, the poor mechanical performance of collagen (i.e., low compressive modulus) makes collagen alone an unsuitable candidate for load-bearing applications, such as bone tissue engineering.8

Bone is composed of approximately 70% inorganic mineral, 20% organic matrix, and 10% water. The mineral content of bone is predominantly hydroxyapatite (HA), while the organic matrix is composed mainly of type I collagen (∼90%) and small amounts (∼10%) of noncollagenous proteins (NCPs), such as osteonectin and osteocalcin.9 Biomechanically, the inorganic mineral (i.e., HA) endows bone with its rigid structural framework, while collagen confers bone with its elastic properties.10

To mimic the natural bone composition, prevailing scaffolds for bone tissue engineering are collagen–hydroxyapatite (Col/HA) composites. To fabricate a Col/HA composite, a conventional method utilizes standing mineral solutions that contain supersaturated calcium phosphate ions to presoak a porous collagen scaffold.11–14 The problem is that the high calcium phosphate ion concentrations cause the minerals to precipitate out of solution rather than only crystallizing on the collagen scaffold. As a result, the mineral content is deposited on the surface of the collagen fibers rather than within them, which often obstruct the pores of the collagen scaffold.15 Another common preparation method premixes collagen and synthetic HA nanoparticles to form collagen–apatite slurry.16–24 This mixing technique mechanically blends collagen and HA to form a physical mixture that lacks a strong mineral/collagen integration and interaction. In addition, synthetic HA nanoparticles are often different in the crystal size and crystalline phase from the HA found in natural bone.8,25 As a result, the Col/HA composites that are fabricated using this technique usually possess poor mechanical properties with diminished osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties.18 These conventional in vitro collagen mineralization methods are different from the in vivo bone formation process and often result in scaffolds that are unsuitable for bone tissue engineering.26

The natural bone formation process is comprised of two stages: primary and secondary osteogenesis.27 In primary osteogenesis, bone formation is initiated from pre-existing cartilage (i.e., endochondral osteogenesis), in which HA crystals form in an unorganized manner (i.e., woven bone) within a proteoglycan matrix and do not form close association with collagen. Therefore, when attempting to mimic the bone formation process using collagen, primary osteogenesis is not discussed. In secondary osteogenesis, the primary woven bone is remodeled into a more organized structure by embedding nanoscopic HA crystals primarily within collagen fibers, a process termed intrafibrillar mineralization.28,29

In bone formation, intrafibrillar mineralization requires NCPs (e.g., osteonectin and osteocalcin), a low concentration of mineral ions, and extracellular fluid (ECF) flow.30–32 NCPs are thought to play a fundamental role in the mineralization process by binding the calcium and phosphate ions that are present in the ECF, and thereby creating a liquid amorphous calcium phosphate phase, termed polymer-induced liquid-precursor (PILP).33 Due to the high affinity of the NCPs to collagen and the fluidic character of the PILP, the calcium phosphate precursor can infiltrate into the collagen fibrils. The amorphous calcium phosphate phase later leaves off water and transforms into the more thermodynamically stable crystalline form within the collagen fibers.33,34

To emulate the intrafibrillar mineralization process of secondary osteogenesis, previous work33 has used a calcium phosphate solution containing micromolar amounts of a negatively charged acidic polypeptide (i.e., polyaspartic acid). The polyaspartic acid functions as the NCPs in vivo by inhibiting the nucleation of HA crystals within the mineral solution, while inducing amorphous precursor droplets to infiltrate into the collagen fibers.33–35 This important work utilized a standing mineral solution to emulate the physiological ECF. However, this static PILP mineralization method is dependent on the penetration depth of the PILP phase, which is limited to a distance of 100 μm in dense collagen substrates.36 Thus, the static PILP mineralization method is not suitable for mineralization of collagen scaffolds in sizes that are clinically relevant for tissue engineering applications.

To further improve the intrafibrillar mineralization technique, this study incorporates a continuous perfusion flow (referred to as dynamic intrafibrillar mineralization) to mimic the flow of the ion-containing ECF that occurs in vivo. The continuous perfusion of the amorphous fluid phase replenishes the mineral ions to the collagen scaffold, and thereby increases the efficiency of the intrafibrillar mineralization. The perfusion flow also facilitates a rather uniform mineral deposition throughout the collagen scaffold that results in a homogenous Col/HA composite. This study compares efficiency, homogeneity, and mechanical properties of the Col/HA composites fabricated by static and dynamic intrafibrillar mineralization. It is shown that the Col/HA composites fabricated via dynamic intrafibrillar mineralization resemble human trabecular bone both in structure and composition. This study also indicates that the resultant Col/HA composites can provide a mechanically stable environment that is biocompatible, biodegradable, and suitable for human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) growth.

Materials and Methods

Porous collagen scaffold preparation

Type I collagen from bovine tendon was blended at 15,000 RPM on ice in 0.05 M of acetic acid. Following homogenization, 10× phosphate-buffered saline and 1 N sodium hydroxide were added to yield a 1% collagen suspension with a pH of 7.4. The collagen suspension was subsequently casted into a prepared mold and left to polymerize for 2 h at 37°C. The polymerized suspension was frozen by lowering the freezer temperature from room temperature to a final freezing point of −10°C at a rate of 0.9°C/minute. The frozen suspension was then lyophilized to create a highly porous structure. To enhance the mechanical strength of the collagen, the lyophilized scaffolds were chemically crosslinked using 40 mM N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide and 20 mM N-hydroxy-succinimide (NHS) for 24 h. Following a second lyophilization, the collagen scaffolds were loaded into a perfusion flow system to be mineralized.

Perfusion-based mineralization

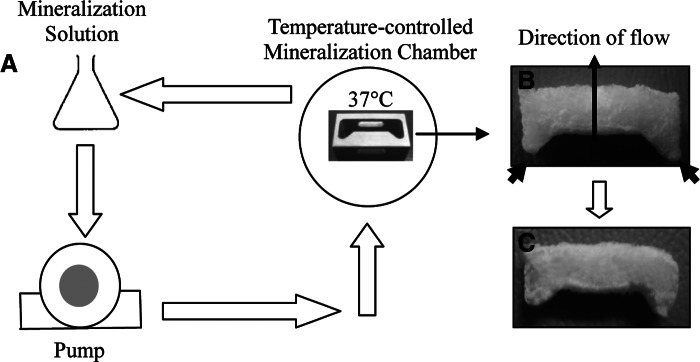

Figure 1A shows a schematic representation of the perfusion-flow (i.e., dynamic) system. Mineralization was performed using a Tris-based mineralization solution containing 4.2 mM K2HPO4, 9 mM CaCl2, and 15 μg/mL of polyaspartic acid.34 A 3×3×11 mm3 porous collagen scaffold (Fig. 1B) was designed with side protrusions and housed inside a stainless steel mold to direct the flow through the center of the scaffold and prevent the fluid from flowing around it. To provide a localized 37°C mineralization environment, the collagen scaffold was placed inside a temperature-controlled chamber, while maintaining the rest of the mineralization solution at ambient temperatures to inhibit crystal growth.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of a dynamic mineralization set up. (B) Picture of a collagen scaffold (with the dimension of 3×3×11 mm3) before dynamic mineralization. Side protrusions, marked by the black arrows in (B), are designed to fit the stainless steel mold inside the mineralization chamber to prevent fluid from flowing around the scaffold. (C) Picture of the scaffold after 24 h of mineralization.

To regulate the degree of mineralization, and thus the mechanical strength of the composites, mineralization was stopped at three predetermined time points of 24, 48, and 72 h. To demonstrate that the dynamic mineralization is more efficient, collagen scaffolds were also mineralized under static conditions (i.e., no-flow) in an oven at 37°C using the same mineralization solution and time.

Morphological evaluation

To examine the effect of mineralization on the collagen scaffolds, a Zeiss EVO50-EP environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) was used to compare nonmineralized collagen, and Col/HA composites after 24, 48, and 72 h of mineralization. For high-resolution images, specimens were gold coated, whereas for low-resolution images, specimens were mounted as is (i.e., not gold-coated), and imaged at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

To evaluate the effect of mineralization on the overall porosity of the composites, a helium pyncometer was used to quantify the skeletal volume of the composite. Porosity was calculated using the formula:

|

where the bulk volume is calculated from the geometric dimensions of the specimen and the skeletal volume is the volume measured by the device.

To assess whether the mineralization process was indeed intrafibrillar, composites mineralized for 24 h via the static and dynamic mineralization processes were imaged on a JEOL 200CX transmission electron microscope (TEM) at 100,000× magnification and 200-kV accelerating voltage. For this analysis, bright-field, dark-field, and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) modes were used. For specimen preparation, samples were pulverized in liquid nitrogen, dispersed in methanol, and added drop-wise onto a copper TEM grid with a carbon support film.

Mineral content examination

To verify the presence and distributions of calcium and phosphorus in the mineralized composites, an IXRF Model 550i energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was utilized. To determine whether the distribution of minerals is homogenous throughout the composites, sections from the surface and the center of the 3-mm-thick composites were compared after static and dynamic mineralization. To determine the effect of time on the degree of mineralization, intensities of the calcium phosphate peaks were evaluated and compared among composites of different mineralization time. In addition, composites mineralized for 48 h via static and dynamic mineralization were compared to evaluate the effectiveness of the two methods. For all samples, at least 3 locations were analyzed and counts averaged for specimen representation.

To evaluate the levels of organic and inorganic components in composites mineralized for 24 h via the static and dynamic mineralization methods, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted on a TA Instruments Model SDT 600. For this analysis, the temperature was ramped from room temperature to 1200°C at 10°C/min while purging nitrogen gas.

To evaluate the mineral phase of the calcium phosphate elements, X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of crushed samples of human cadaver trabecular bone, a 72-h mineralized Col/HA composite, and powder precipitated from the mineral solution were compared for their crystallographic structure. The XRD spectra were also compared to the powder diffraction profile of HA obtained from the International Centre for Diffraction Data. All measurements were collected on a Siemens Kristalloflex 805 X-ray diffractometer at 40 kV and 30 mA using a Cu tube over a 2θ range of 10°–60°.

Mechanical evaluation

The mechanical behavior of elastomeric open-cell foams is well defined. Specifically, three distinct regions can be readily identified from the stress–strain curve of open-cell foams under compression; these regions are the linear elastic region, the collapse plateau region, and the densification region.3 Open-cell collagen scaffolds with an interconnected porous structure behave as elastomeric foams under compression. Therefore, the stress–strain curve of the Col/HA composite is expected to contain the same three regions. Three dry samples of nonmineralized collagen and composites mineralized for 24 h via static and dynamic systems were analyzed. Unconfined compression tests were performed using a parallel plate with a 1-kg load cell at a strain rate of 0.5% on a TA.XTPlus Texture Analyzer. Modulus of elasticity was calculated using linear regression from the linear region of the stress–strain curves.

MSC biocompatibility evaluation

In cell culture studies to show the biocompatibility of the mineralized Col/HA composites, thin composite discs with the dimensions of 1 cm diameter and 1 mm thickness were used to facilitate nutrient delivery to cells throughout the scaffolds. About 1.5×105 passage 3 hMSCs were seeded on two sets of four Col/HA composite discs. The first set included four uncoated discs: nonmineralized collagen and Col/HA composites mineralized statically for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. The second set of four identical discs was coated with fibronectin for 2 h at 37°C before cell seeding. Fibronectin coating was expected to enhance cell attachment to the Col/HA discs and to qualitatively demonstrate potential differences in cell attachment and spreading between coated and uncoated scaffolds. Following 2 h of initial cell attachment, the α-Minimum Essential Media (supplemented with 15% prescreened fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine) was added to the composite discs. The discs were then cultured inside a 37°C humidified incubator (5% CO2-95% air) for a period of 4 weeks. To evaluate cell viability, composites were assayed with a fluorescent Live/Dead Cell Viability Kit. Using this live/dead assay, both nucleus and cytoplasm of viable cells are stained green (Ex/Em ∼495 nm/∼515 nm), whereas the nucleus of dead cells is stained orange (ex/em ∼528 nm/∼617 nm). To examine the cellularity and extracellular matrix (ECM) distribution throughout the composites, the Col/HA discs were fixed in 10% formalin, cut to 5-μm cross sections, and stained with the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. All fluorescence and histological images were acquired using a Nikon TE2000 fluorescence inverted microscope.

Results

Morphological evaluation

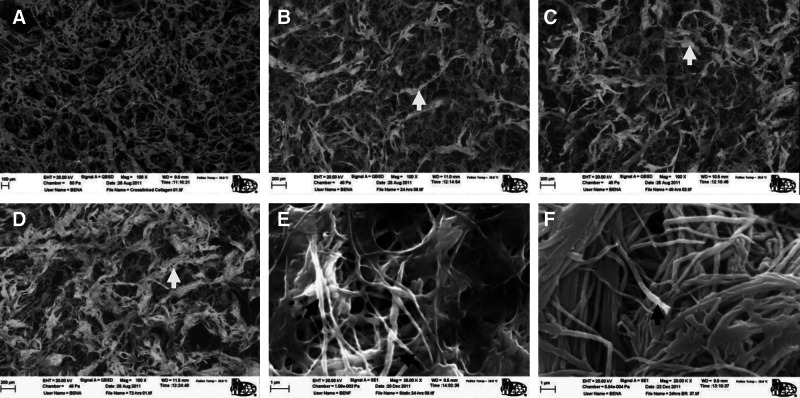

Figure 2 shows ESEM images of nonmineralized collagen and Col/HA composites mineralized for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. Before mineralization, the open-cell collagen scaffold has the mean pore size of ∼200 μm with an overall porosity of 97.7%. Following mineralization, the Col/HA composites retained the porous structure and only had a slight decrease in porosity to 95.7% after 24 h of dynamic mineralization. ESEM images shown in Figure 2B–D demonstrate an increasing level of mineralization with the increase of mineralization time. The degree of mineralization is indicated by the thickness of the Col/HA fibers (i.e., struts). The high-magnification ESEM images in Figure 2E and F compare the static versus dynamic PILP mineralization and illustrate a more uniform mineralization through the dynamic method. The figures also show that both methods achieved intrafibrillar mineralization, that is, the minerals are within the collagen fibers.

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron micrographs compare the microstructures of a collagen scaffold before mineralization (A) and collagen–hydroxyapatite (Col/HA) composites mineralized for 24 h (B), 48 h (C), and 72 h (D), respectively. Col/HA fiber bundles are indicated by white arrows (B–D). Composites mineralized for 24 h via the static (E) and dynamic (F) methods are compared for their mineralization homogeneity. Intrafibrillar mineralization is indicated by the black arrows.

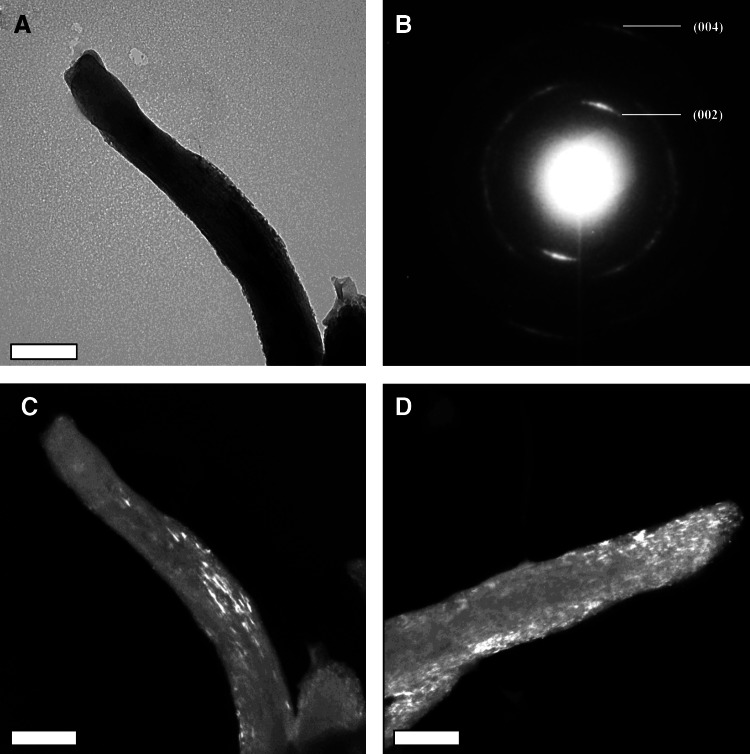

To further confirm the intrafibrillar mineralization, transmission electronic microscopy analysis was employed to analyze the mineralized Col/HA composites. Figure 3 further confirms that the mineralization achieved by the PILP method is indeed intrafibrillar via both the static and dynamic mineralization methods. The d-spacing of the crystal lattices was calculated using a SAED pattern of evaporated aluminum with a camera constant of 82 cm. The crystal planes were then derived from the d-spacing values and compared against JCPDS standards of HA. The diffraction pattern (Fig. 3B) is very similar to that of bone, dominated by arcs of most of the crystal planes, such as 002 and 004 reflections.34,37 Moreover, the longer axis of the HA crystals is parallel to the long axis of the collagen fiber, as illustrated by the bright crystal streaks seen throughout the dark field images of mineralized collagen via static (Fig. 3C) and dynamic (Fig. 3D) mineralization methods. There does not appear to be surface mineral; thus, the TEM dark field image and SAED pattern indicates the presence of intrafibrillar mineralization.38

FIG. 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of a mineralized collagen fiber using bright field (A), selected area electron diffraction (B), and dark field (C, D) modes in a composite mineralized for 24 h via the static (C) and dynamic (D) mineralization methods. The parallel orientation of HA crystals seen throughout the collagen fibers as white streaks in the dark field images (C, D) suggests intrafibrillar mineralization. Scale bar is 0.2 μm.

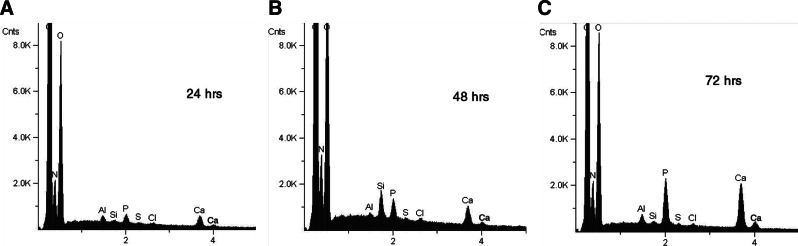

Mineral content evaluation

The EDS data shown in Figure 4 demonstrate that after mineralization all the Col/HA composites exhibited calcium and phosphorus elements. Furthermore, calcium phosphorus peak amplitudes correspond to the mineralization time of the composites; that is, peak amplitude increases with mineralization time.

FIG. 4.

Energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) of thin collagen discs after static mineralization of 24 h (A), 48 h (B), and 72 h (C), respectively.

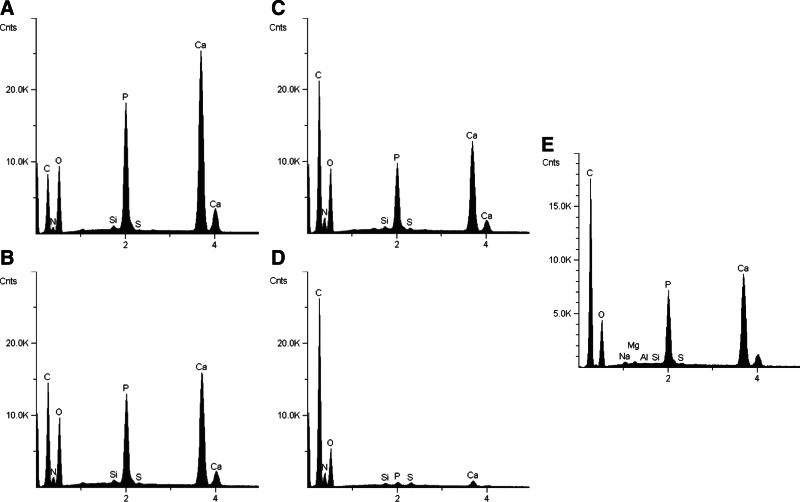

Figure 5 compares the EDS between Col/HA composites that were mineralized via static and dynamic mineralization processes together with human trabecular bone. The comparison between the surface and center cross sections from a 3-mm-thick scaffold reveal that mineral distribution was rather homogeneous in the composite that was mineralized via the dynamic mineralization process (Fig. 5A, C). Conversely, a marked difference in the degree of mineralization can be seen between the surface and the center of a composite that was mineralized via the static mineralization process (Fig. 5B, D). Evidently, the dynamic process generated composites with more mineral content than the static process in a same period of time. This fact is shown through the larger calcium phosphorus peaks in the composites that were mineralized via the dynamic system (Fig. 5A, C). Furthermore, similar mineral peaks were exhibited by the Col/HA composite mineralized for 48 h via the dynamic process and human trabecular bone (Fig. 5C, E).

FIG. 5.

EDS of sections from the surface (A, B) and the center (C, D) of the composites mineralized for 48 h via dynamic (A, C) and static (B, D) mineralization methods and human trabecular bone (E).

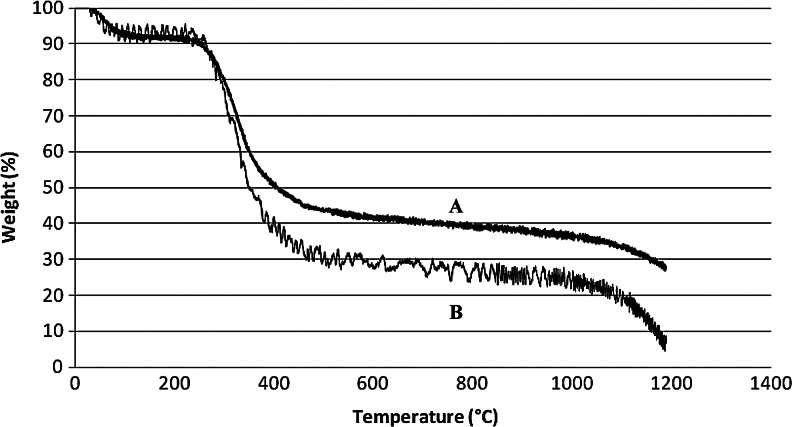

The mineral content was also evaluated quantitatively using TGA analysis. Figure 6 compares the loss in the normalized weight with the increase in temperature for composites mineralized via the static and dynamic methods for 24 h. From the graph, it was determined that the composite mineralized via the static method contains ∼5% water (between 0°C–100°C), ∼65% organic phase (i.e., collagen) decomposed between ∼250°C–550°C, and ∼30% inorganic phase (i.e., HA), which began decomposing after 800°C (B in Fig. 6). In comparison, the composite that was dynamically mineralized contained a higher mineral content, with a composition of: ∼5% water, ∼50% organic, and ∼45% inorganic phase (A in Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Thermogravimetric analysis curves of Col/HA composites mineralized for 24 h via the dynamic (A) and static (B) mineralization methods.

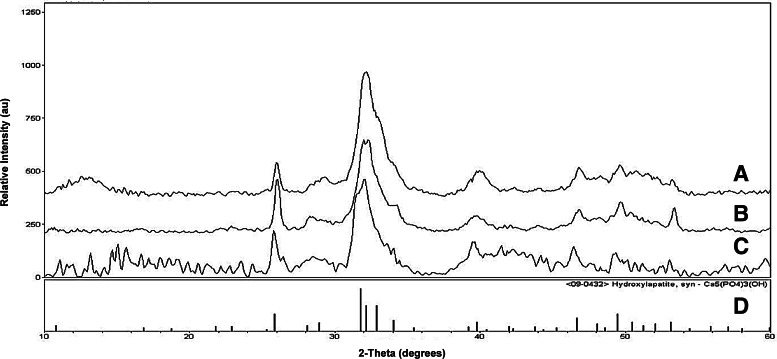

The mineral phase analysis shown in Figure 7 contains the XRD spectra obtained from samples of a trabecular bone, a precipitate from the mineral solution, and a Col/HA composite mineralized for 72 h via the dynamic process. The spectra were compared with the XRD spectrum of HA obtained from The International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) library. The XRD spectra confirmed that the calcium phosphate molecule is indeed HA. In addition, the similar XRD peak widths demonstrate that the Col/HA composites possess small nanocrystals, similar to that of human trabecular bone.

FIG. 7.

X-ray diffraction spectra of trabecular bone (A), mineral solution precipitates (B), 72-h composite mineralized via the dynamic system (C), and HA from International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) (D).

Mechanical properties

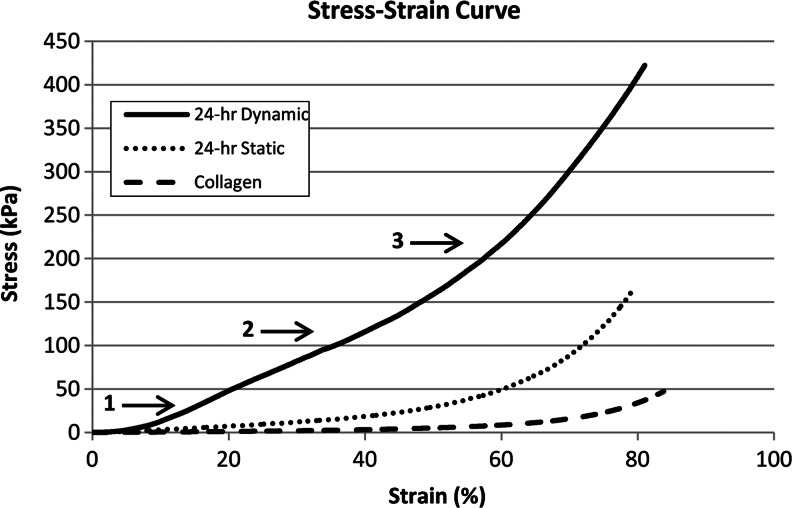

Figure 8 compares the compressive stress–strain curves of a nonmineralized collagen scaffold and Col/HA composites mineralized via static and dynamic processes for 24 h, respectively. From the stress–strain curve, it is evident that the Col/HA composite mineralized via the dynamic process system is much stiffer than that mineralized via the static process. The Col/HA composite mineralized via the dynamic process exhibited a steeper slope seen even at small strains. This steeper slope most likely stems from the mineral reinforcement of the collagen struts facilitated more effectively via the dynamic intrafibrillar mineralization process. This fact is also shown quantitatively in Table 1 through the modulus of elasticity (E), which was calculated from the linear region of the stress–strain curves. As expected, three distinct regions (1: the linear elastic region, 2: the collapse plateau region, and 3: the densification region) were readily identified from the stress–strain curves, indicating that the collagen scaffold and Col/HA composite retain their porous structure similar to the open-cell structure of elastomeric foams.

FIG. 8.

Stress–strain curves of nonmineralized collagen, and Col/HA composites mineralized for 24 h via static and dynamic processes. The three characteristic regions expected for elastomeric foams are readily identified from the stress–strain curve.

Table 1.

Modulus of Elasticity (E) of Collagen and Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Composites Mineralized for 24 h via Static and Dynamic Processes, Respectively

| Sample | E (kPa) |

|---|---|

| 24-h via dynamic process | 200.5±129.4 |

| 24-h via static process | 39±18.8 |

| Nonmineralized collagen | 6.7±2.1 |

Measurements were taken under dry conditions (n=3).

MSC biocompatibility analysis

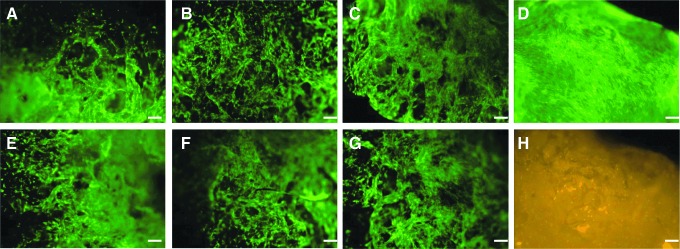

Fluorescent Live/Dead images shown in Figure 9 demonstrate that hMSCs were viable (shown by the green fluorescence) and readily proliferated on the Col/HA discs. No significant difference in initial cell attachment and spreading was observed between the fibronectin-coated and uncoated Col/HA composites. Additionally, images acquired at day 19 (Fig. 9D, H) revealed that cells were fully confluent on the Col/HA composites with only a small number of dead cells (whose nuclei are shown in orange fluorescence).

FIG. 9.

Green fluorescent images of live human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) cultured on fibronectin-coated (A–C) and uncoated (E–G) Col/HA composites at day 3; mineralization times are 24 h (A, E), 48 h (B, F), and 72 h (C, G), respectively. Fibronectin-coated 48-h composite shows fully confluent live cells in green (D) and the nuclei of few dead cells in orange (H) at day 19. Scale bar is 100 μm.

The enhancement of mechanical stability after mineralization was already apparent by day 3 as the nonmineralized collagen constructs exhibited significant shrinkage due to cell-mediated contraction (CMC). In contrast, minimal shrinkage was seen on the mineralized Col/HA composites (data not shown).

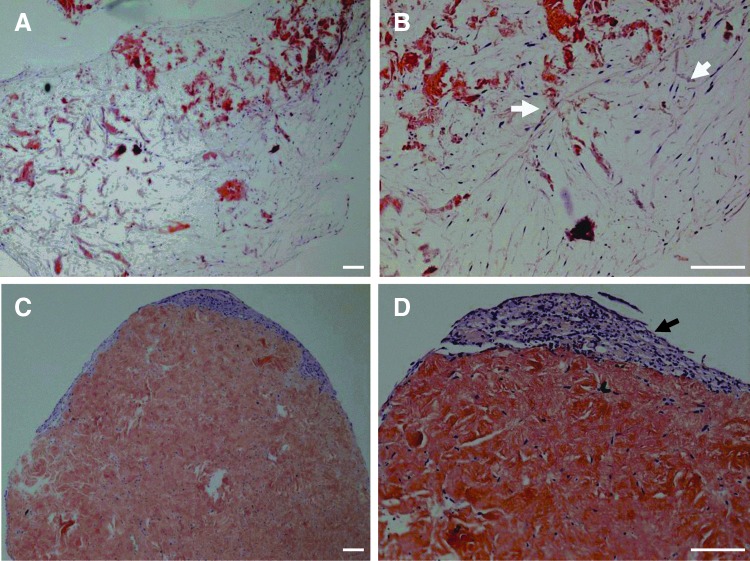

Figure 10 shows H&E-stained images of a nonmineralized collagen scaffold and a Col/HA composite mineralized for 48 h. Following 26 days in culture, uniform cell distribution was evident throughout the mineralized Col/HA composite with nearly a complete remodeling of the construct (Fig. 10A, B). Through this remodeling process, the Col/HA construct was replaced by an extensive layer of ECM that was deposited by the hMSCs. In contrast, due to the collapse of the nonmineralized collagen, only minimal cellular infiltration took place and as a result, cells were only seen on the periphery of the construct with very little cellularity or remodeling in the center of the construct (Fig. 10C, D).

FIG. 10.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained images of a 48-h mineralized Col/HA composite (A, B) and nonmineralized collagen scaffold (C, D) after 26 days of cell culture; magnifications are 40× (A, C) and 100× (B, D), respectively. White arrows in (B) show cellular infiltration with extensive construct remodeling; black arrow in (D) indicates cells at the periphery with minimal cellular infiltration. Scale bar is 250 μm for all figures.

Discussion and Conclusion

Conventional mineralization methods using a supersaturated calcium phosphate solution or synthetic HA nanoparticles to fabricate Col/HA composites for bone tissue engineering do not lead to a biomimetic bone-like nanostructure. These methods result in superficial and heterogeneous mineralization of collagen and, therefore, these composites do not provide an appropriate environment for cell and tissue growth. In contrast, the in vivo bone formation process occurs primarily through the intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen.

In this study, the PILP process was recapitulated by utilizing polyaspartic acid in a perfusion-flow system. The fluid flow replenished the influx of mineral ions and promoted the intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen, thereby mimicking the bone formation process. This dynamic mineralization resulted in a biomimetic Col/HA composite consisting of HA crystals that were embedded within the collagen fibers. This deposition technique facilitated a high degree of mineralization to the core of the scaffold within a short time frame. The dynamic mineralization approach proved more efficient than the static method, in which mineralization is limited by diffusion and, therefore, has a more limited depth of mineral penetration into the collagen scaffold. This aspect becomes particularly important when attempting to fabricate larger mineralized scaffolds that are intended for tissue engineering applications.

The effects of mineralization on the morphology of the collagen scaffold were examined by ESEM, helium pycnometry, and TEM images. The results confirmed that regardless of mineralization time, the Col/HA composites retained their interconnected porous structure and their overall porosity was only slightly decreased (2% decrease). It was also demonstrated that the mineralization process is controllable; an increase in mineralization time resulted in thicker collagen fiber bundles that are embedded with more HA crystals. To substantiate this, elemental analysis using EDS demonstrated that an increase in mineralization time-generated composites that possess a higher mineral content. Additionally, images obtained through TEM analysis verified that the HA crystals were primarily embedded within collagen fibers (i.e., intrafibrillar mineralization).

To examine the mineral content of the Col/HA composites and compare the static and dynamic mineralization methods, XRD, EDS, TGA, and mechanical tests were employed. XRD analysis verified that the mineral phase is indeed HA. Furthermore, the spectrum obtained from a dynamically mineralized Col/HA composite exhibited similar XRD spectra to that exhibited by human trabecular bone, thus illustrating their close resemblance. Mineral content analysis using EDS and TGA revealed much higher HA contents on composites that were mineralized via the dynamic process. Mechanical compression tests supported this data. A sixfold increase in modulus of elasticity was found for Col/HA composites that were dynamically mineralized compared to composites mineralized via the static process.

Finally, the Col/HA composites with intrafibrillar mineralization are biocompatible and have an excellent surface property for cell attachment and growth. Live/Dead fluorescence staining revealed that hMSCs readily proliferated on the Col/HA composites with little cell death. The fibronectin coating of the Col/HA discs had no apparent effect on initial cell attachment and spreading, which showed that the composition of the Col/HA discs alone is adequate to support hMSC culture. Histological staining using H&E demonstrated an extensive remodeling of the Col/HA composites by the hMSCs, with uniform cell distribution throughout the composite. In contrast, the nonmineralized collagen constructs exhibited significant shrinkage due to CMC of hMSC following 3 days in culture. The mechanical instability of the nonmineralized collagen scaffold resulted in its contraction and its eventual collapse, which prevented the cells from migrating and infiltrating into the collagen construct. As a result, the hMSCs were only seen at the periphery with little cellularity at the center of the construct. For tissue engineering applications, and particularly for bone tissue engineering, such a construct does not provide adequate physical support for cellular proliferation and tissue integration, and, as a result, could lead to failure during in vivo implantation. This fact exemplifies the importance of sufficient mechanical strength in a scaffold design.

In conclusion, the data presented in this study provide compelling evidence to demonstrate the value of perfusion-flow as a novel dynamic mineralization technique for bone tissue engineering applications. The utility of this perfusion-based technique can be further extended to other tissue engineering applications using different materials. For example, heparin can be dynamically incorporated into scaffolding materials as an anticoagulant coating agent for cardiovascular tissue engineering applications. In this study, the dynamic mineralization process facilitated the deposition of HA crystals within collagen fibers more effectively than the static mineralization technique. As a result, the Col/HA composites were similar to trabecular bone in both structure and composition. Additionally, cell culture studies confirmed that the Col/HA composite is highly biocompatible and can be remodeled into a cell-derived ECM and therefore easily integrated into native tissue. Future work will focus on utilizing this Col/HA composite as a three-dimensional scaffolding for both in vitro and in vivo cell culture studies. These studies will aim to develop a biomimetic bone marrow environment composed of an ECM-coated Col/HA composite to support the proliferation of hMSCs while retaining their stemness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: 1R21 HL102775-01.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Liu X. Ma P.X. Polymeric scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:477. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017544.36001.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma L. Gao C. Mao Z. Zhou J. Shen J. Biodegradability and cell-mediated contraction of porous collagen scaffolds: the effect of lysine as a novel crosslinking bridge. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71:334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harley B.A. Leung J.H. Silva E.C. Gibson L.J. Mechanical characterization of collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:463. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikada Y. Challenges in tissue engineering. J R Soc Interface. 2006;22:589. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleford M.R. Oh S. Oh N. Ong J.L. In vivo study on hydroxyapatite scaffolds with trabecular architecture for bone repair. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;89:1019. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karageorgiou V. Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glowacki J. Mizuno S. Collagen scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biopolymers. 2008;89:338. doi: 10.1002/bip.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl D.A. Czernuszka J.T. Collagen-hydroxyapatite composites for hard tissue repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2006;28:43. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v011a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:S131. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04151206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viguet-Carrin S. Garnero P. Delmas P.D. The role of collagen in bone strength. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:319. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du C. Cui F.Z. Zhang W. Feng Q.L. Zhu X.D. de Groot K. Formation of calcium phosphate/collagen composites through mineralization of collagen matrix. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:518. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000615)50:4<518::aid-jbm7>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamauchi K. Goda T. Takeuchi N. Einaga H. Tanabe T. Preparation of collagen/calcium phosphate multilayer sheet using enzymatic mineralization. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5481. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Z. Tian J. Yu B. Xu Y. Feng Q.A. Bone-like nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen loaded injectable scaffold. Biomed Mater. 2009;4:055005. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/4/5/055005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girija E.K. Yokogawa Y. Nagata F. Apatite formation on collagen fibrils in the presence of polyacrylic acid. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2004;15:593. doi: 10.1023/b:jmsm.0000026101.53272.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lickorish D. Ramshaw J.A. Werkmeister J.A. Glattauer V. Howlett C.R. Collagen-hydroxyapatite composite prepared by biomimetic process. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:19. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi M. Itoh S. Ichinose S. Shinomiya K. Tanaka J. Self-organization mechanism in a bone-like hydroxyapatite/collagen nanocomposite synthesized in vitro and its biological reaction in vivo. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1705. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prosecka E. Rampichova M. Vojtova L. Tvrdik D. Melcakova S. Juhasova J., et al. Optimized conditions for mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts on a collagen/hydroxyapatite matrix. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;99:307. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pek Y.S. Gao S. Arshad M.S. Leck K.J. Ying J.Y. Porous collagen-apatite nanocomposite foams as bone regeneration scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4300. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wahl D.A. Sachlos E. Liu C. Czernuszka J.T. Controlling the processing of collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:201. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0682-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J.C. Han D.W. Suh H. A bone replaceable artificial bone substitute: morphological and physiochemical characterizations. Yonsei Med J. 2000;41:468. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2000.41.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao S. Watari F. Uo M. Ohkawa S. Tamura K. Wang W., et al. The preparation and characteristics of a carbonated hydroxyapatite/collagen composite at room temperature. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;74:817. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akkouch A. Zhang Z. Rouabhia M. A novel collagen/hydroxyapatite/poly (lactide-co-ɛ caprolactone) biodegradable and bioactive 3D porous scaffold for bone regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;96:693. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh S. Kikuchi M. Koyama Y. Matumoto H.N. Takakuda K. Shinomiya K., et al. Development of a novel biomaterial, hydroxyapatite/collagen (HAp/Col) composite for medical use. Biomed Mater Eng. 2005;15:29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos M.H. Valerio P. Goes A.M. Leite M.F. Heneine L.G. Mansur H.S. Biocompatibility evaluation of hydroxyapatite/collagen nanocomposites doped with Zn+2. Biomed Mater. 2007;2:135. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/2/2/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eanes E.D. Hailer A.W. Anionic effects on the size and shape of apatite crystals grown from physiological solutions. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66:449. doi: 10.1007/s002230010090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stiehler M. Seib F.P. Rauh J. Goedecke A. Werner C. Bornhauser M., et al. Cancellous bone allograft seeded with human mesenchymal stromal cells: a potential good manufacturing practice-grade tool for the regeneration of bone defects. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:658. doi: 10.3109/14653241003774052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karperien M. Roelen B. Poelmann R. de Groot A.G. Hierck B. Deruiter M., et al. Morphogenesis, generation of tissue in the embryo. In: Van Blitterswijk C., editor. Tissue Engineering. San Diego: Elsevier, Inc.; 2008. pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lees S. Page E.A. A study of some properties of mineralized turkey leg tendon. Connect Tissue Res. 1992;28:263. doi: 10.3109/03008209209016820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu L. Kim Y.K. Liu Y. Ryou H. Wimmer C.E. Dai L., et al. Biomimetic analogs for collagen biomineralization. J Dent Res. 2011;90:82. doi: 10.1177/0022034510385241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hidehiro O. Kazuto H. Norio A. Current concepts of bone biomineralization. J Oral Biosci. 2008;50:1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshed M. McKee M.D. Molecular determinants of extracellular matrix mineralization in bone and blood vessels. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:359. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283393a2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillsley M.V. Frangos J.A. Bone tissue engineering: the role of interstitial fluid flow. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;43:573. doi: 10.1002/bit.260430706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gower L.B. Biomimetic model systems for investigating the amorphous precursor pathway and its role in biomineralization. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4551. doi: 10.1021/cr800443h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olszta M.J. Cheng X.G. Jee S.S. Kumar R. Kim Y.Y. Kaufman M.J., et al. Bone structure and formation: a new perspective. Materials Science & Engineering R-Reports. 2007;58:77. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cölfen H. Biomineraliztion a crystal-clear view. Nat Mater. 2010;9:960. doi: 10.1038/nmat2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thula T.T. Rodriguez D.E. Lee M.H. Pendi L. Podschun J. Gower L.B. In vitro mineralization of dense collagen substrates: a biomimetic approach toward the development of bone-graft materials. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:3158. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biswas K. Basu B. Suri A.K. Chattopadhyay K. A TEM study on TiB2-20%MoSi2 composite: microstructure development and densification mechanism. Scripta Mater. 2006;54:1363. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nudelman F. Pieterse K. George A. Bomans P.H.H. Friedrich J. Brylka L.J., et al. The role of collagen in bone apatite formation in the presence of hydroxyapatite nucleation inhibitors. Nat Mater. 2010;9:1004. doi: 10.1038/nmat2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]