Abstract

Background

There is currently a need to develop and test in vitro systems for predicting the toxicity of nanoparticles. One challenge is to determine the actual cellular dose of nanoparticles after exposure.

Methods

In this study, human epithelial lung cells (A549) were exposed to airborne Cu particles at the air–liquid interface (ALI). The cellular dose was determined for two different particle sizes at different deposition conditions, including constant and pulsed Cu aerosol flow.

Results

Airborne polydisperse particles with a geometric mean diameter (GMD) of 180 nm [geometric standard deviation (GSD) 1.5, concentration 105 particles/mL] deposited at the ALI yielded a cellular dose of 0.4–2.6 μg/cm2 at pulsed flow and 1.6–7.6 μg/cm2 at constant flow. Smaller polydisperse particles in the nanoregime (GMD 80 nm, GSD 1.5, concentration 107 particles/mL) resulted in a lower cellular dose of 0.01–0.05 μg/cm2 at pulsed flow, whereas no deposition was observed at constant flow. Exposure experiments with and without cells showed that the Cu particles were partly dissolved upon deposition on cells and in contact with medium.

Conclusions

Different cellular doses were obtained for the different Cu particle sizes (generated with different methods). Furthermore, the cellular doses were affected by the flow conditions in the cell exposure system and the solubility of Cu. The cellular doses of Cu presented here are the amount of Cu that remained on the cells after completion of an experiment. As Cu particles were partly dissolved, Cu (a nonnegligible contribution) was, in addition, present and analyzed in the nourishing medium present beneath the cells. This study presents cellular doses induced by Cu particles and demonstrates difficulties with deposition of nanoparticles at the ALI and of partially soluble particles.

Key words: in vitro exposure system, air–liquid interface, copper particles, nanoparticle deposition, nanoparticle dissolution, cellular doses, nanotoxicology

Introduction

The lung is constantly exposed to airborne particles. On a daily basis, a person can inhale 20 m3 of air, resulting in deposition of airborne particles on the epithelial surface of the lung. Effects related to particle exposure are increased risk for cardiopulmonary diseases and lung cancer, as well as exacerbation of asthma and development of allergy in the early years of life.(1,2) Air pollutants are estimated to account for 800,000 premature deaths every year.(3) In recent years, special awareness has been drawn to potential health effects induced by particles in the size range of approximately 1–100 nm, often referred to as ultrafine particles or nanoparticles. Several studies on cells have shown a wide range of toxic effects, including DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell death after nanoparticle exposure.(4–7) Such studies on toxic effects have often been performed in submerged cultures and the toxicity commonly observed at doses around 10–100 μg/mL, thus at relatively high doses considering doses likely in the lung. With an increased use and manufacture of products containing nanoparticles, there is an urgent need to investigate potentially adverse effects on human health due to exposure to these nanomaterials.

When addressing toxicity following inhalation, there is a need of a system that resembles the lung. Such an approach is also beneficial in order to evaluate the effects of drugs to be delivered to the respiratory tract. In in vitro exposure studies, cells are often exposed to particles in a liquid suspension. In an attempt to more closely resemble the exposure situation in the lung, systems have been developed where cells at the air–liquid interface (ALI) are exposed to airborne particles. Such an approach has been used to study the health effects of diesel exhaust,(8) cigarette smoke,(9) fly ash particles,(10) and ultrafine carbon particles,(11) and also effects of iron, gold, and silver nanoparticles.(12)

Different methods have been applied to determine the deposition efficiency of particles at the ALI of in vitro exposure systems. Calculations based on known particle deposition in a stagnation-point aerosol flow of a designed exposure system have been used to determine the amount of deposited particles.(11,13) These studies concluded that 2% of the total number of particles were deposited on the cells in the ALI. One of these studies also verified the calculated results by quantitative analysis of particles from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images.(13) Similar studies have been conducted on fine and ultrafine fly ash particles(10) with a deposition efficiency of 2.3% determined in separate runs with deposition and subsequent analysis of ultrafine sodium fluorescein particles on transwell inserts without cells. An on-line method to determine the mass of deposited particles in the ALI in a cell exposure system has been reported in which one of the transwell inserts was replaced with a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) to enable direct monitoring of the deposited particle mass.(14) This study showed 1.2–1.4 times higher deposition rates compared with results obtained with fluorescein sodium dosimetry. All deposition efficiency assessments described above were performed without cells, i.e., none of the studies accounted for particle solubility.

The particle solubility is strongly material-dependent and is also influenced by surface characteristics. As the particle size decreases, the presence of heterogeneities and defects in the material will have an increased effect on the dissolution properties.(15,16) As a consequence, the surface reactivity of a massive sheet is totally different compared with both micrometer- and nano-sized particles. As Cu nanoparticles in earlier studies have been shown to be highly reactive and soluble to a large extent in cell test media,(17) this process has likely influenced the cellular doses determined here.

The aim of this study was to determine the cellular dose of well-characterized partly soluble Cu particles in the ALI at different exposure conditions. The cellular dose is defined here as the remaining mass of Cu present on (or in) the cells after completion of an exposure experiment. The particle-size distribution and particle concentration were determined prior to deposition with a differential mobility particle sizer (DMPS). The cellular dose of total Cu metal was analyzed with atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), determined for exposures at constant and pulsed particle aerosol flow and for differently sized Cu particles generated with a furnace and a rotation brush generator (RBG), respectively. Initial tests of the cell viability were performed for the 180-nm Cu aerosol in comparison with a stream of filtered aerosol (without particles) with the same gas composition.

Materials and Methods

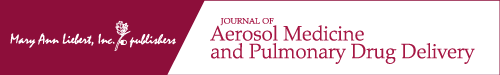

A generated aerosol of Cu particles (with a furnace or an RBG) was alternatively directed on-line to a DMPS for size characterization, or to the cell exposure system (Cultex, Vitrocell Systems GmbH, Waldkirch, Germany). For depositional and cell viability studies, see Figure 1. The particle generator was connected to the particle sizer and the cell exposure system with stainless steel tubing to minimize particle deposition on the tube walls.

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the experimental setup including particle generation with a furnace (or alternatively with an RBG), particle characterization with a DMPS, and particle exposure to cells in a cell exposure system (Cultex) at the ALI. A filter was placed prior to the inlet to the cell exposure system to obtain control exposures.

Particle generation

A high-temperature furnace was used to generate an aerosol of Cu nanoparticles. Cu metal (Sigma–Aldrich, product no. 326445, purity 99.999%) was positioned in a container inside a furnace tube (both made of alumina) set at a temperature of 1,620°C to create a vapor pressure of 133 Pa (P=1 Torr).(18) Water-cooled stainless steel ends were attached to the alumina furnace tube. Particles were formed by cooling the Cu vapor at the furnace exit. The particle aerosol was transported to the next unit of the system using a flow of nitrogen gas (99.996 vol%, 600 mL/min) in stainless steel tubing.

Alternatively, an RBG was used for Cu particle aerosol generation. Cu nanopowder (Sigma–Aldrich, product no. 634220, 99.8%) was fed at a speed of 9 mm/hr in the RBG, and the rotation brush was set at maximum speed (1,200 rpm). Pressurized air (250 kPa) was used to aerosolize the nanopowder. Aggregates larger than 0.6 μm were removed by an impactor prior to the DMPS characterization or contact with the cell exposure system.

On-line particle characterization

The airborne particles were transported to a DMPS for measurement of the particle-size distribution of the aerosol in the size range of 10–800 nm (detection interval). Particles were charged by using a bipolar charger prior to the entrance of the DMPS. The DMPS included a differential mobility analyzer (DMA) and a condensation particle counter (CPC; model 3022, TSI GmbH, Aachen, Germany). The DMA measures the electrical mobility particle diameter, which is defined as the diameter of a sphere with the same charge that has the same speed of migration in a unit electrical field. For agglomerates, the electrical mobility diameter may be larger than the volume equivalent diameter. The total particle number that entered the DMPS (or alternatively the in vitro cell exposure system) was corrected for particle losses due to the particle-charge distribution, as described in another study.(19) Multiply charged particles were also corrected for, but not the diffusion and impaction losses of particles in the DMA. A closed loop of sheath air was used for the DMA, including a filter for particle removal. The sheath air was pumped with an external pump (3 L/min) and cooled by passage through wound stainless steel tubing. The sample-to-sheath flow ratio was 1:10. An outlet prior to the DMPS passed excess aerosol to the exhaust ventilation. Particle-size distributions of airborne particles were monitored before and after deposition on cultured cells. As the length of the stainless steel tubes from the particle generators to the DMPS was the same as that from the generators to the cell exposure system, the size and concentration of the particles entering the exposure system with the cell cultures were approximately equal to the particle size and concentration measured with the DMPS. The geometric mean diameter (GMD), the geometric standard deviation (GSD), and the number concentration of the particle-size distribution are presented.

Particle deposition

After completion of the particle characterization with the DMPS, the airborne Cu particles from the furnace (or the RBG) were redirected to the cell exposure system (Cultex) exposing human lung cells (A549) at the air–cell interface. Cells were grown on membranes (4.2 cm2, 0.4-μm pore size) in transwell cups. Three transwells with cells were exposed simultaneously. The cells were nourished with medium [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 22320-022, supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin] from the bottom via the membranes, i.e., no medium covered the cells. The medium contained HEPES for its buffering capacity. A peristaltic pump exchanged the medium underneath the transwells with fresh medium at a flow of 0.1 mL/min. The temperature of the cell exposure system was kept constant (37°C) by using circulating water. An aerosol flow of 20 mL/min (controlled with three mass flow meters and a pump after the cell exposure system) passed through each of the three transwells. A bypass flow of 0.5 L/min was used during all deposition experiments. A constant or a pulsed aerosol flow allowed particles to enter the transwells. Automatic valves were used before and after the cell exposure system to control the pulse frequency during pulsed aerosol flows: 1 min open/2.5 min closed, or alternatively 10 sec open/10 sec closed. The Cu particle/nitrogen aerosol from the furnace was mixed with oxygen and carbon dioxide to reach a gas composition of 75:20:5 vol% of N2:O2:CO2. The particle/air aerosol from the RBG was mixed with 5 vol% CO2, prior to entrance into the cell exposure system to equal the gas mixture in normal cell cultivation. The particle exposure experiments lasted 4 hr. This exposure time was considered suitable because rather acute toxic effects had been observed in earlier Cu nanoparticle exposure experiments with submerged cell cultures.(17) A filter removed all particles prior to one of the cell cultures in the exposure system to obtain control exposures.

Off-line particle characterization

The cellular dose of Cu was analyzed with AAS. The cellular dose includes Cu remaining on/in the cells after completion of an exposure experiment, without taking into consideration any dissolved copper entering the nourishing medium beneath the cells. The medium is continuously exchanged, and the dissolved fraction is therefore removed from the exposure system. A few analyses were performed to determine the presence of Cu in the medium beneath the cells. This medium was collected directly in plastic cups (Nalgene® PMP) for consecutive analyses of Cu.

Measurements of total concentrations of Cu were determined using either graphite furnace AAS for sub–parts-per-billion to parts-per-billion (micrograms per liter) concentrations or a flame AAS for parts-per-billion to parts-per-million (milligrams per liter) concentrations. The Cu concentration was determined for all three transwells of the cell exposure system and for three repeated experiments. To enable analysis of the cellular dose of Cu, the membrane (including the cells and deposited particles) of each transwell was removed with a scalpel and placed in a plastic cup (Nalgene PMP, 50 mL) with 10 mL of nitric acid (50/50 vol/vol of 65% HNO3 suprapure and ultrapure deionized water). After 10 min of sonication (ultrasonic bath), the membrane was removed and the Cu concentration determined by means of AAS.

Analysis of Cu concentrations with AAS was performed under standard operational conditions and was based on three replicate readings of each sample. Analyses of blanks (membranes without deposited particles as well as pure medium) were performed to monitor background concentrations of Cu in the experimental setup. Calibration curves were verified consecutively during analysis, and quality controls using standard solutions were run every tenth sample. The detection limits of Cu were 1 μg/L (graphite furnace) and 6 μg/L (flame), which correspond to Cu cellular doses of 0.002 and 0.01 μg/cm2, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples were prepared to enable elemental and visual analyses of deposited particles on cells. After exposure, the cells (in transwells) were removed from the cell exposure system and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a six-well plate and stored in a refrigerator. The membranes with the cells were cut into thin slices, transferred to Eppendorf tubes, and rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The membranes were then postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4°C for 2 hr, dehydrated in ethanol followed by acetone, and finally embedded in LX-112 (Ladd Research Industries, Burlington, VT). The samples were contrasted with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate and thereafter visualized using TEM (Tecnai 12 Spirit Bio TWIN, 100 kV; Fei Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). A TEM (JEM 2100, 120 kV, LaB6 filament; Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS; Jeol) was used for visualization and elemental analyses. Noncontrasted samples were examined by means of SEM (JSM7401 F, 15 kV) with a scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) detector. Particle size and shape were also examined by means of TEM (Tecnai F30 ST, 300 kV; Fei Company) under dry conditions, i.e., no cells were cultured on the transwell membranes and no nourishing medium was placed beneath the membranes. Under dry conditions, particles were deposited directly onto carbon-covered Cu TEM grids, positioned directly on the transwell membranes in the cell exposure system.

The deposition efficiency was determined by comparing the total mass of Cu remaining on/in the cells after completion of a cell exposure experiment (analyzed with AAS) with the total mass of Cu particles passing the cell exposure system during a 4-hr-exposure experiment. Dissolved Cu in the media was not taken into account when determining the deposition efficiency. Therefore, the total deposition efficiencies (including particles and dissolved fraction of Cu) were in most cases larger than the values presented here. Dissolved Cu has previously been shown to be more toxic than particulate Cu.(17) Furthermore, the dissolved fraction was not considered to essentially contribute to the toxicity of Cu, because the medium containing the dissolved fraction was continuously exchanged and removed from the exposure system. The total mass of Cu passing the cell exposure system was assessed from the particle number size distribution (measured with DMPS) and the density of Cu. By using the size distribution (and not the mean size), the sizes of all particles were taken into account. However, as the particles were not spherical but agglomerated, the mass of each particle as well as the total mass of Cu passing the exposure system may be overestimated, and furthermore the deposition efficiencies of Cu underestimated. At constant flow, the total mass of Cu was calculated for the total volume of Cu aerosol passing the cell exposure system. At pulsed flow, the total mass of Cu available for deposition was calculated in two ways, depending on the different deposition conditions for furnace- and RBG-generated Cu aerosols. As furnace-generated particles were deposited more or less only under stationary conditions, these calculations of the total mass of Cu available for deposition onto the cells were based on the aerosol volume (3 mL of aerosol per pulse and per transwell excluding the aerosol inlet) present in the Cultex system under these conditions. RBG-generated particles were deposited under both flowing and stationary conditions during the pulsed-flow exposure experiments. In this case, the mass of Cu passing the transwells during flow conditions was added to the mass of Cu present in the transwells during stationary conditions to calculate the total mass of Cu available for deposition.

Cell cultivation

Human lung cells (A549 type II epithelial cell line; from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultivated in cell culture flasks using DMEM (41965-039) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. One day prior to the exposure experiments, 0.4 million cells were seeded at each transwell (2 mL with 0.2 million cells/mL) and placed in six-well plates with 3 mL of DMEM beneath the transwell membranes. The cells grew and reached a close-to-confluent cell layer at the day of exposure. At the time of exposure, the cell medium was removed and the cells attached on the semipermeable membrane of the transwell washed with 1 mL of PBS before the transwells were transferred to the cell exposure system.

Analysis of cell viability

Cell viability was measured using trypan blue staining. Cells with compromised cell membranes were stained by trypan blue, whereas viable cells with intact cell membrane were not stained. After exposure, the transwells were removed from the cell exposure system and the cells were washed two times with 500 μL of PBS and trypsinated with 100 μL of trypsin for 5 min in a humidified atmosphere (37°C, 5% CO2). DMEM (500 μL) was added to inactivate the trypsin. The removed PBS and the cell suspension were collected and centrifuged (1 min at 6,000 rpm). All but 200 μL of the supernatant was removed, and 40 μL of the remaining cell suspension was mixed with 40 μL of trypan blue. After incubation (3 min), the percentage of nonstained cells was counted in a Bürker chamber as a measure of cell viability.

Results

Particle-size distribution

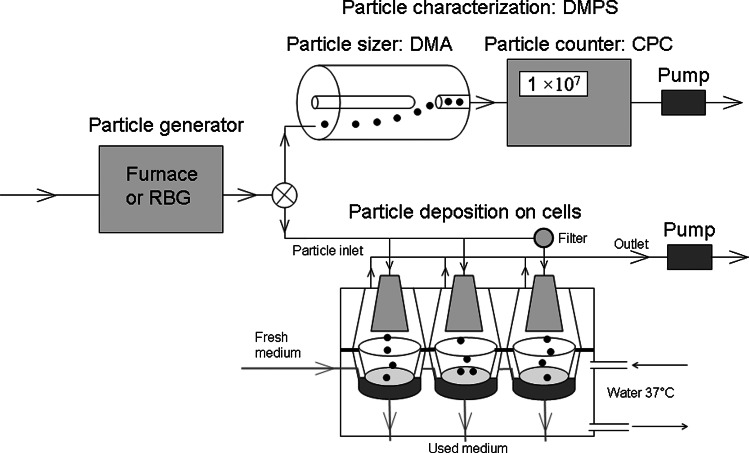

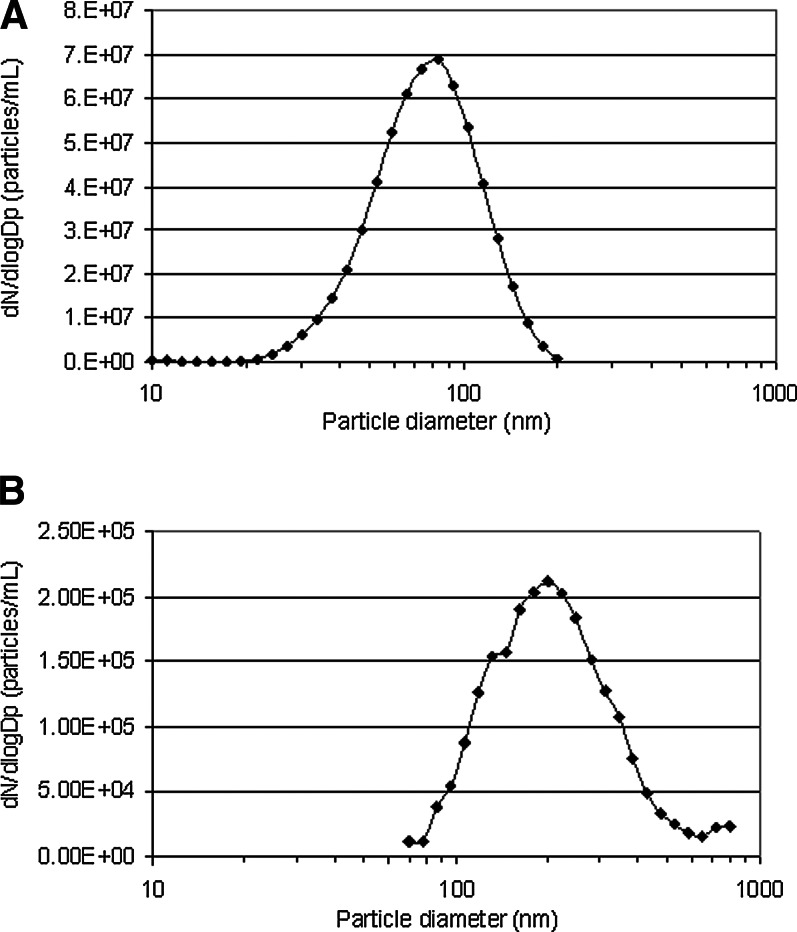

Generation of airborne polydisperse Cu particles by aerosolization of Cu nanopowder with an RBG mainly resulted in particles between 100 and 300 nm, with a GMD of 180 nm and a GSD of 1.5 (Fig. 2B). These particles were, in fact, agglomerates of smaller particles, sized less than 100 nm according to TEM observations (Fig. 3C; particles deposited directly on TEM grids without cells), and also in agreement with the supplier specification of the Cu nanopowder. The concentration of these airborne so-called 180-nm-sized Cu particles was determined to be 105 particles/mL, which was possible to deposit at the ALI under both pulsed- and constant-flow conditions.

FIG. 2.

The particle-size distribution of airborne Cu particles generated by (A) evaporation of Cu metal in a high-temperature furnace (107 particles/mL, GMD 80 nm, GSD 1.5) and (B) aerosolization of Cu nanopowder in an RBG (105 particles/mL, GMD 180 nm, GSD 1.5).

FIG. 3.

TEM micrographs show (A, B) 80-nm furnace-generated Cu particles (pulsed flow/dry conditions) and (C) 180-nm RBG-generated Cu particles (constant flow/dry conditions) deposited on TEM grids put on transwell membranes without cells in the exposure system.

Freshly generated airborne polydisperse Cu particle aerosols with the high-temperature furnace mainly resulted in particles between 50 and 120 nm, with a GMD of 80 nm and a GSD of 1.5 (Fig. 2A), and a concentration of 107 particles/mL. Furnace-generated Cu particles deposited under pulsed-flow conditions as individual particles or agglomerates, in a few cases with primary particle sizes as large as 200 nm, but often below 100 nm (Fig. 3A; particles deposited directly on TEM grids without cells). The TEM investigation furthermore revealed attachment of particles with primary particle sizes less than 5 nm onto the larger-sized particles (Fig. 3B). None, or possibly few, of the so-called 80-nm-sized particles deposited at the ALI under constant-flow conditions.

Cellular dose

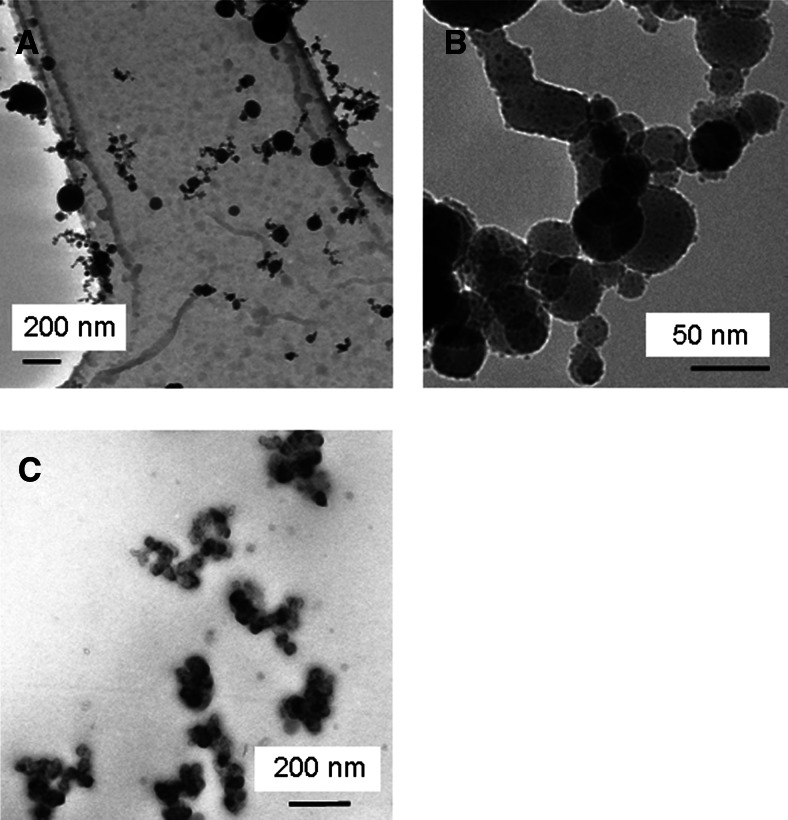

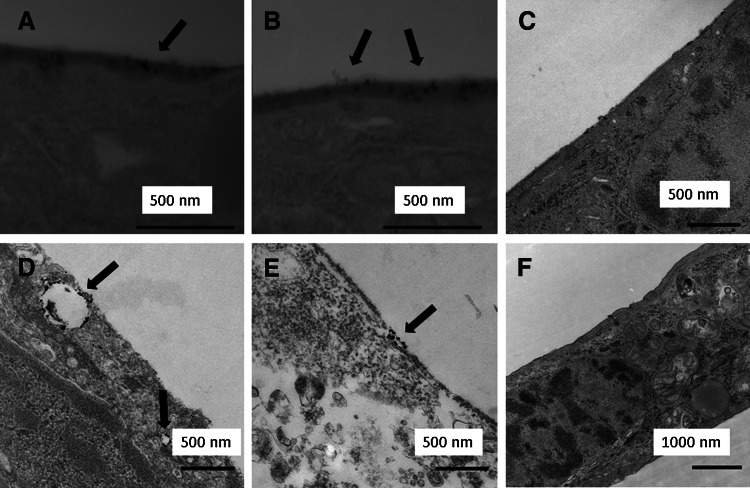

The cellular doses of Cu that remained on/in the cells after a 4-hr experiment are shown in Table 1 for the different exposure conditions. No, or very few, 80-nm-sized particles deposited on the cells at a constant Cu aerosol flow, yielding a cellular dose of Cu similar to the level of the controls (0–0.01 μg/cm2). Pulsed aerosol flows slightly increased the cellular dose of the same particles to 0.01–0.05 μg/cm2. The two different sets of pulsed flow (frequencies: 10 sec/10 sec or 1 min/2.5 min) yielded about the same cellular dose of Cu irrespective of pulse frequency. The observed cellular dose corresponds to a deposition efficiency of up to 0.05% of the total amount of Cu present in the aerosol in each transwell under stationary (i.e., no flow) conditions during a pulsed-flow experiment. Deposition of Cu particles onto the cells under these conditions was verified by means of TEM (Fig. 4A and B). No deposition occurred at the surface of the control (Fig. 4C).

Table 1.

Cellular Doses

| GMD (nm) | Flow condition | Cellular dose (μg/cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | Constant | 0.01 |

| 80 | Pulsed (1 min/2.5 min) | 0.01–0.05 |

| 80 | Pulsed (10 sec/10 sec) | 0.01–0.05 |

| 180 | Constant | 1.6–7.6 (4.1) |

| 180 | Pulsed (1 min/2.5 min) | 0.4–2.1 (1.3) |

| 180 | Pulsed (10 sec/10 sec) | 0.3–2.6 (1.2) |

Cellular doses of Cu particles generated with a high-temperature furnace (GMD 80 nm, 107 particles/mL) and an RBG (GMD 180 nm, 105 particles/mL) at constant or pulsed aerosol flows (1 min/2.5 min or 10 sec/10 sec open/closed) are presented. Cellular doses in parentheses represent mean values. The level of the controls was 0.01 μg/cm2.

FIG. 4.

Images of human lung cells exposed to (A, B) a pulsed flow of 80-nm Cu particles from the furnace visualized using STEM and (D, E) a constant flow of 180-nm Cu particles from the RBG visualized using TEM. The arrows in D and E indicate the locations of Cu particles. (C, F) TEM images of control cells exposed to the filtered aerosol in experiments using the furnace and the RBG, respectively. The Cu content of the particles in A, B, D, and E was confirmed with EDS.

A significantly larger cellular dose of Cu was observed for the larger-sized (180 nm) Cu aerosol, although the total mass of airborne Cu particles entering the transwells was approximately seven times higher for the 80-nm Cu aerosol due to the 100-fold higher concentration of these particles. RBG-generated particles (180 nm) deposited under both constant- and pulsed-flow conditions. Constant-flow conditions resulted in a cellular dose of 1.6–7.6 μg/cm2 (corresponding to a deposition efficiency of 1.1% on average), whereas with pulsed flows (10 sec/10 sec and 1 min/2.5 min), the cellular dose of Cu was lower, between 0.3 and 2.6 μg/cm2. Similar to findings for the 80-nm-sized Cu aerosol, the cellular dose was independent of the applied pulse frequency. The deposition efficiency of the 180-nm Cu particles was up to 1.1% of the total calculated amount of Cu present in the aerosol in each transwell under stationary (no flow) and flowing conditions during a 4-hr pulsed-flow experiment. TEM/EDS analysis of cells exposed to these particles under constant-flow conditions revealed particles at the cell surface (Fig. 4D and E). No particles were observed at the surface of control cells (Fig. 4F).

Particle dissolution

Partial dissolution occurred upon deposition of Cu particles on the cell membranes and in contact with the cell medium. This process was observed via random measurements of the Cu concentration in the cell medium during the 180-nm Cu particle exposure experiments. After 4 hr of exposure, the measured Cu concentrations in the medium were approximately 20 μg/L and 90 μg/L under pulsed and constant Cu aerosol flow conditions, respectively. However, no measurable concentrations of Cu were observed in the medium beneath the cells in any of the experiments with 80-nm particles. The measured basal level of Cu was 4 μg/L in the nourishing medium. No particles could dissolve during exposure experiments performed under dry conditions (i.e., when using transwell membranes without cultured cells and nourishing medium). At a constant flow of 80-nm Cu particles, the amount of Cu deposited on the dry membrane was still at the level of the controls (0.01 μg/cm2). This suggests that the Cu nanoparticles did not deposit at any time at constant flow during cell exposure. The deposition of 80-nm Cu particles was improved, however, by using a pulsed flow (1 min/2.5 min) with a deposited amount of particles on the dry membrane varying between 0.2 and 0.6 μg/cm2.

Particle toxicity

The viability of the control cells after a 4-hr exposure in the cell exposure system with filtered aerosols (i.e., without particles) was 87±5% (n=6). Cells exposed to a constant flow of 180-nm Cu particles (cellular dose 1.6–7.6 μg/cm2) for 4 hr showed a cell viability of 44±7% (n=4). No decrease in the fraction of viable cells [88±4% (n=8)] was observed for cellular doses lower than 0.05 μg/cm2 for the 80-nm Cu particles.

Discussion

The RBG enables particle aerosol generation of non–freshly-generated powders, which means that the particle surfaces already are naturally aged and oxidized to different extents. Exposure to such particles, however, is of increasing importance today, because there is increased production, handling, and use of engineered nanopowders and particulate products. Nano-sized airborne particles were not easily created via the RBG dispersal of nanopowders. The GMD of airborne particles was 180 nm, and only a small fraction of the airborne particles were smaller than 100 nm (Fig. 2B). However, these airborne particles were all aggregates of smaller nano-sized particles. Several grams of Cu nanopowder were used during 4 hr of continuous dispersal by using the RBG. A high flow of pressurized air (P=250 kPa) aerosolized the nanopowder, but only a small fraction of the aerosol (a few milligrams) was diverted to the cell exposure system because a high flow of air would harm the cells. The main part of the nanopowder mass was therefore wasted and never transferred to the cell exposure system.

The furnace, on the other hand, easily generated fresh nano-sized Cu particles (GMD 80 nm) at a high concentration (107 particles/mL) by evaporating only a few tenths of a gram of Cu during 4 hr. Hence, the cells in the laboratory setup can be exposed to particles with characteristics similar to those of airborne particles formed in industrial processes (e.g., at melting, grinding, and welding).(20)

The cellular doses of Cu at the ALI varied depending on the different deposition conditions (Table 1). The greatest difference in cellular doses was observed between experiments depositing either 80- or 180-nm Cu particles. A significantly higher cellular dose was observed for 180-nm Cu particles compared with the 80-nm particles. The cellular dose at constant flow (1.6–7.6 μg/cm2), furthermore, was three to 13 times higher compared with the maximum dose yielded with the smaller particles, even though the total amount of Cu available for deposition entering the cell exposure system was about seven times higher for the 80-nm Cu particles (2.1 μg/cm3) compared with the 180-nm Cu particles (0.3 μg/cm3).

Different aerosol flow conditions (constant and pulsed flow at two different frequencies) influenced the observed cellular dose of Cu (Table 1). Airborne 180-nm Cu particles were deposited at the ALI at both constant and pulsed flows, whereas a pulsed flow was required to allow deposition of 80-nm Cu particles. As practically no 80-nm particles from the furnace deposited at constant flow, a pulsed flow was applied to allow a longer time for diffusion in the vicinity of the cells, and hence increase the deposition of small particles in the exposure system (although a pulsed flow also resulted in a lower total amount of Cu that passed through each transwell during 4 hr). A similar approach has been applied when exposing cells in a Cultex system to puffs of freshly generated cigarette smoke.(9) This approach allowed particles to deposit on the cells by sedimentation and furthermore enabled efficient exposure of both vapor and particles in spite of their different diffusion efficiencies. Other studies, including studies on carbon nanoparticles generated by spark discharging,(13) diesel exhaust generated by a diesel generator,(21) and gold, silver, and iron nanoparticles generated by spark ablation,(12) have succeeded in depositing freshly made nanoparticles at constant flow at the ALI.

In this study, a pulsed flow enabled deposition of 80-nm Cu particles as visualized with TEM imaging (Fig. 4A and B). The use of different pulse frequencies (1 min/2.5 min and 10 sec/10 sec constant flow/no flow) did not change the deposition efficiency. Both pulse frequencies yielded the same cellular doses.

For RGB-generated 180-nm Cu particles, the flow conditions also affected the cellular dose. The highest cellular dose was obtained using a constant aerosol flow in the cell exposure system. In contrast to observations with the 80-nm Cu particles, a lower cellular dose was obtained at pulsed flows. A constant aerosol flow allowed a higher total amount of particles to enter the cell exposure system during 4 hr compared with a pulsed flow, because no new particles entered when the flow was turned off. As the larger-sized Cu particles did deposit at a constant flow, the pulsed flow did not increase the cellular dose. Both pulse frequencies (1 min/2.5 min and 10 sec/10 sec constant flow/no flow) yielded similar cellular doses for the 180-nm Cu particles.

Total or partial dissolution of particles also influenced the cellular dose of Cu, i.e., the amount of Cu remaining on/in the cells after completion of an exposure experiment. This effect was not taken into account when determining the cellular dose, which in this study did not include the dissolved fraction. As the Cu particles in previous studies have been shown to be highly soluble,(17,22) the total amount of deposited Cu is considered underestimated. Dissolved Cu was shown in separate measurements to end up in the medium beneath the cells/the transwell membranes. A non-100% confluent layer of cells and semipermeable transwell membranes allowed dissolved Cu to enter into the medium, an effect confirmed by the analysis of Cu in the medium collected during exposure experiments with 180-nm Cu particles. Indeed, a better control of the confluency using, for example, transepithelial electric resistance in future studies may be preferred. In agreement with an observed higher cellular dose of 180-nm Cu particles at a constant flow compared with pulsed flow, the concentration of dissolved Cu in the medium was higher under constant-flow conditions.

Nonmeasurable concentrations of Cu could be determined in the medium beneath the cells during exposure to 80-nm Cu particles. However, as a relatively large volume of the freshly renewed medium was collected during the exposure, the Cu concentration did not rise above the basal level in the medium. The total mass of 80-nm Cu particles was therefore analyzed under dry conditions, i.e., on transwell membranes without cultured cells and nourishing medium beneath the membrane. A pulsed flow of 80-nm particles (1 min/2.5 min) yielded Cu mass concentrations between 0.2 and 0.6 μg/cm2 on the dry membrane. These concentrations are higher than the observed cellular dose of Cu using the same exposure conditions, which indicate that the 80-nm Cu particles also partly dissolve in contact with the cells. The results are in agreement with recent findings showing a considerable dissolution of Cu nanoparticles submerged in cell culture medium (DMEM) after 4 hr in cell exposure experiments.(17,22) At a constant flow, the amount of Cu on the dry membrane was similar to the observed cellular dose and the level of the controls (0.01 μg/cm2). These results indicate that practically no 80-nm Cu particles deposit at a constant aerosol flow in the cell exposure system.

The goal is to develop in vitro systems that are more and more sensitive, which makes it possible to evaluate doses that are relevant to realistic nanoparticle flux delivered to the lung. The deposition at the ALI is a step in the right direction concerning this question, but further effort is needed to get a system that even better matches the lung and also allows investigations of the effects of very low doses of particles and other substances. Actually, the doses applied in the present study are much more realistic than those most often used in publications to date. A dose of 0.01 μg/cm2 in our study is equal to a dose flux of 0.0025 μg/cm2/hr. This is actually lower than a workplace dose flux, because the dose flux to the lungs may be double that in a workplace, i.e., 0.005 μg/cm2/hr.(23) Furthermore, a cellular dose of 4.1 μg/cm2 in our study is equal to 1.025 μg/cm2/hr. That means that after 1 hr the cells are exposed to a dose that could be obtained after approximately 8 days.(23) In all, this means that the doses used in our study are not extreme when considering workplace exposure.

In this study, deposition efficiencies of Cu particles were estimated by measuring the total mass of Cu on/in the actual cells that remained after an exposure experiment compared with the total particle mass that entered the cell exposure system in the aerosol. The calculated deposition efficiency of Cu particles ranged from 0.05 to 1.1%. These findings are lower or in the same range as those in other reported investigations of particle deposition at the ALI. The lower values reported in this study actually reflect the fact that Cu particles dissolve to a large extent during experiments, and consequently do not contribute to the presented cellular dose. Furthermore, the total mass of Cu entering the cell exposure system may be overestimated, because the generated particles are not exactly spherical, and therefore also contribute to underestimated deposition efficiencies. If dissolution and particle-shape factors were taken into account, the deposition efficiency of particles would be higher. Further studies are necessary to quantify this effect.

Other studies have used different techniques to measure the deposition efficiency. Computed deposition efficiencies have been presented for ultrafine diesel particles at the ALI in a cell exposure system; they range from 0.20 to 7.25%, depending on different particle and flow characteristics.(24) Reported deposition efficiencies varied with particle diameter and increased at higher material densities for 200- and 500-nm-sized particles and for lower flow velocities. The highest deposition efficiency (about 7%) was observed for particle sizes of 10 nm and 1 μm, and the lowest for particles of 200 nm (0.65%) and of 100 and 300 nm (0.95%) (ρ=1.2 g/cm3). Other studies present calculated deposition efficiencies of particles at the ALI in cell exposure systems. Ultrafine carbon particles (concentration 2×106 particles/mL, GMD 95 nm) deposited in a scaled-up version of a Minucell perfusion unit resulted in a calculated deposition efficiency of 2%.(11) The amount of particles deposited on the cells was concluded to vary between 0.044 and 0.230 μg/cm2 in 6-hr experiments. Another study exposed fly ash particles with a concentration of 3.6×104 particles/mL and a GMD of 165 nm to cells at the ALI in a Cultex system by using powder dispersion with a rotating brush.(10) The reported deposition efficiency (2.3%) was determined in separate runs with deposition and subsequent analysis of ultrafine sodium fluorescein particles on transwell inserts without cells. Fluorescent-model particles have also been used to estimate particulate deposition of diesel exhaust.(20) Ultrafine carbon (D=90 nm, 3×106 particles/mL) and fine polystyrene particles (D=196 nm, 1.6×104 particles/mL) were deposited at the ALI in a Minucell perfusion cell.(13) A deposition efficiency of 2% was reported by comparing the calculated number of deposited particles and the total number of particles passing the cells during the time of exposure. Particle deposition measurements with QCM have also been presented where the deposited amount was based on the deposition of particles on the microbalance without cells or alternatively on aluminum foils.(14,25) A deposition efficiency of up to 7.2% was reported for a deposition area corresponding to two standard plates with six-transwell inserts.(25) The particle deposition efficiencies for the above-mentioned studies were, in many cases, determined by calculations or assessed by using alternative poorly soluble particles. This means that the deposition of the particles actually studied was not assessed, but rather that of particles of similar sizes and shapes that may or may not deposit to the same extent. Furthermore, all of the studies assessed the deposition efficiency without cells and cell culture medium, i.e., none of the studies accounted for particle solubility. In the present study, Cu particles were found to dissolve under the experimental conditions, and therefore influence the deposition efficiency as assessed from the cellular dose.

No toxic effects were observed for 80-nm particle cellular doses of 0.01–0.05 μg/cm2, although deposition under dry conditions indicated that the totally deposited dose of these particles was higher. If the same particle deposition efficiency at the dry membrane surface and at the ALI is assumed, the total dose of 80-nm particles to which the cells would be exposed would be 0.2–0.6 μg/cm2 (corresponding to a total deposition efficiency of 0.6% on a dry membrane). The total dose including particles and dissolved fraction of 80-nm particles, however, was too low to yield any toxic effects. Note that the cellular dose was not present on the cells during the whole experiment, but increased with time to reach the final dose after 4 hr. The lack of toxicity could also be due to (a) the continuous removal of medium, which decreased the time of exposure to the dissolved fraction, and (b) the fact that particles and ions may have different toxic effects. We recently showed in a study where cells were exposed to Cu nanoparticles that cell death occurs mainly due to the Cu particles and only to a minor extent due to the dissolved Cu. More than 90% of the cells died when exposed to Cu nanoparticles, whereas the cell death was 12% for the corresponding dissolved Cu fraction.(17) This effect has also been observed for other particles, such as cobalt, cobalt oxide, and manganese oxide nanoparticles.(26,27) It is therefore possible that the cellular dose of Cu particles in cell exposure experiments presented here mainly affected the cell viability and that the dissolved Cu had only a minor influence. Regarding 180-nm particles, cellular doses of 1.6–7.6 μg/cm2 showed toxic effects. The presence of Cu in the medium indicates that the total dose exposing the cells was even higher.

The most common in vitro particle exposure method uses cells submerged in a liquid suspension of particles. The amount of nanoparticles used in these experiments is often between 1 and 100 μg/mL. These amounts may appear higher compared with the cellular doses of Cu in the cell exposure system of this study. However, the cellular dose is rarely measured in submerged cultures, although the delivery of particles from the particle suspension to the adherent cells may differ substantially between different particle composition and sizes.(28) In a recent study, the cellular dose of Cu was determined after exposure and subsequent removal of the Cu nanoparticle suspension, in submerged cell experiments.(22) It was concluded that approximately 15% of the initial amount of Cu added ended up in the cells after 4 hr. Assuming this figure to be relevant for the present study at the ALI, the average cellular dose (4.1 μg/cm2) of 180-nm Cu particles at a constant flow would correspond to approximately 27 μg/cm2 in the submerged cell experiment. The cellular dose is thus in the same range as doses used in some submerged cell experiments.(21) This study and the submerged cell experiment(22) reveal that Cu particles induce cell death at the given exposure conditions. These findings are in line with other in vitro as well as in vivo studies showing toxic effects induced by Cu nanoparticles.(17,29–31)

Concluding remarks

Cellular doses of airborne Cu particles on cell cultures in an in vitro lung cell exposure system under different exposure conditions have been investigated for accurate assessment in subsequent particle toxicity testing. The cellular dose was defined as the remaining amount of Cu (as particles or dissolved) present on or in the cells after completion of an exposure experiment without taking into account any dissolved Cu fraction entering the nourishing medium beneath the cells. The study shows that it is essential to take particle dissolution into account when assessing the cellular dose, a process that occurs to a different extent for soluble and poorly soluble particles in contact with the cells/medium. The study also shows that particles of different sizes (generated with different methods) were deposited to different extents and that different flow conditions largely influenced the cellular dose in the cell exposure system. The 180-nm-sized Cu particles deposited in a significantly higher dose compared with 80-nm-sized Cu particles under both constant and pulsed flows. A pulsed flow that allowed a longer time for diffusion was required to enable deposition of the 80-nm Cu particles in the cell exposure system. The two aerosol-generation methods used—evaporation/condensation of metal by using a furnace and aerosolization of nanopowder by using an RBG—have different advantages and can therefore be recommended in different situations. The furnace can be recommended if a high concentration of fresh airborne nanoparticles (agglomerates) is desirable. The RBG commonly generates lower concentrations than the furnace, and larger airborne particle agglomerates, because it is difficult to disperse the nanopowder into its primary particles. However, in combination with the cell exposure system, the highest cellular doses were obtained for the RBG-generated particles. Therefore, the RGB seems to be a better alternative to use in combination with cell exposure systems based on diffusion.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are members of the Stockholm Particle Group (SPG), an operative network between three universities in Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University, Karolinska Institutet, and the Royal Institute of Technology. Grants from the Swedish Research Council (VR), Ångpanneföreningen's Foundation for Research and Development (ÅForsk), and Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (FORMAS) are gratefully acknowledged. We also acknowledge Kjell Jansson at Stockholm University for the SEM and TEM analyses.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Health aspects of air pollution with particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide. World Health Organization; Bonn, Germany: 2003. Report on a WHO Working Group, EUR/03/5042688. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordling E. Berglind N. Melén E. Emenius G. Hallberg J. Nyberg F. Pershagen G. Svartengren M. Wickman M. Bellander T. Traffic-related air pollution and childhood respiratory symptoms, function and allergies. Epidemiology. 2008;19:401–408. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a1ce3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. The World Health Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlsson HL. Cronholm P. Gustafsson J. Möller L. Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: a comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1726–1732. doi: 10.1021/tx800064j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhabra G. Sood A. Fisher B. Cartwright L. Saunders M. Evans WH. Surprenant A. Lopez-Castejon G. Mann S. Davis SA. Hails LA. Ingham E. Verkade P. Lane J. Heesom K. Newson R. Case CP. Nanoparticles can cause DNA damage across a cellular barrier. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:876–883. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Y. Leifert A. Ruau D. Neuss S. Bornemann J. Schmid G. Brandau W. Simon U. Jahnen-Dechent W. Gold nanoparticles of diameter 1.4 nm trigger necrosis by oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage. Small. 2009;5:2067–2076. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AshaRani PV. Low Kah Mun G. Prakash Hande M. Valiyaveettil S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano. 2009;3:279–290. doi: 10.1021/nn800596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knebel JW. Ritter D. Aufderheide M. Exposure of human lung cells to native diesel motor exhaust—development of an optimized in vitro test strategy. Toxicol In Vitro. 2002;16:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(01)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukano Y. Ogura M. Eguchi K. Shibagaki M. Suzuki M. Modified procedure of a direct in vitro exposure system for mammalian cells to whole cigarette smoke. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2004;55:317–323. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diabaté S. Mülhopt S. Paur HR. Krug HF. The response of a co-culture lung model to fine and ultrafine particles of incinerator fly ash at the air–liquid interface. Altern Lab Anim. 2008;36:285–298. doi: 10.1177/026119290803600306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bitterle E. Karg E. Schroeppel A. Kreyling WG. Tippe A. Ferron GA. Schmid O. Heyder J. Maier KL. Hofer T. Dose-controlled exposure of A549 epithelial cells at the air–liquid interface to airborne ultrafine carbonaceous particles. Chemosphere. 2006;65:1784–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigg J. Tellabati A. Rhead S. Almeida GM. Higgins JA. Bowman KJ. Jones GD. Howes PB. DNA damage of macrophages at an air–tissue interface induced by metal nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2009;3:348–354. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tippe A. Heinzmann U. Roth C. Deposition of fine and ultrafine aerosol particles during exposure at the air/cell interface. J Aerosol Sci. 2002;33:207–218. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mülhopt S. Diabaté S. Krebs T. Weiss C. Paur HR. Lung toxicity determination by in vitro exposure at the air liquid interface with an integrated online dose measurement. J Phys Conf Ser. 2009;170:012008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Midander K. Pan J. Odnevall Wallinder I. Leygraf C. Metal release from stainless steel particles in vitro–influence of particle size. J Environ Monit. 2007;9:74–81. doi: 10.1039/b613919a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Midander K. de Frutos A. Hedberg Y. Darrie G. Odnevall Wallinder I. Bioaccessibility studies of ferro-chromium alloy particles for a simulated inhalation scenario: a comparative study with the pure metals and stainless steel. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2010;6:441–455. doi: 10.1002/ieam.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Midander K. Cronholm P. Karlsson HL. Elihn K. Möller L. Leygraf C. Odnevall Wallinder I. Surface characteristics, copper release and toxicity of nano- and micrometer-sized copper and copper(II) oxide particles: a cross-disciplinary study. Small. 2009;5:389–399. doi: 10.1002/smll.200801220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lide DR, editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry Physics. 90th. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; Boca Raton, FL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiedensohler A. An approximation of the bipolar charge distribution for particles in the submicron size range. J Aerosol Sci. 1988;19:387–389. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elihn K. Berg P. Ultrafine particle characteristics in seven industrial plants. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009;53:475–484. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mep033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seagrave J. Dunaway S. McDonald JD. Mauderly JL. Hayden P. Stidley C. Responses of differentiated primary human lung epithelial cells to exposure to diesel exhaust at an air–liquid interface. Exp Lung Res. 2007;33:27–51. doi: 10.1080/01902140601113088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cronholm P. Midander K. Karlsson H. Elihn K. Odnevall Wallinder I. Möller L. Effect of sonication and serum proteins on copper release from copper nanoparticles and the toxicity towards lung epithelial cells. Nanotoxicology. 2011;5:269–281. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.536268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paur HR. Cassee FR. Teeguarden J. Fissan H. Diabaté S. Aufderheide M. Kreyling WG. Hänninen O. Kasper G. Riediker M. Rothen-Rutishauser B. Schmid O. In vitro cell exposure studies for the assessment of nanoparticle toxicity in the lung: a dialog between aerosol science and biology. J Aerosol Sci. 2011;42:668–692. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desantes JM. Margot X. Gil A. Fuentes E. Computational study on the deposition of ultrafine particles from diesel exhaust aerosol. J Aerosol Sci. 2006;37:1750–1769. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenz AG. Karg E. Lentner B. Dittrich V. Brandenberger C. Rothen-Rutishauser B. Schulz H. Ferron GA. Schmid O. A dose-controlled system for air–liquid interface cell exposure and application to zinc oxide nanoparticles. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2009;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colognato R. Bonelli A. Ponti J. Farina M. Bergamaschi E. Sabbioni E. Migliore L. Comparative genotoxicity of cobalt nanoparticles and ions on human peripheral leukocytes in vitro. Mutagenesis. 2008;23:377–382. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gen024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limbach LK. Wick P. Manser P. Grass RN. Bruinink A. Stark WJ. Exposure of engineered nanoparticles to human lung epithelial cells: influence of chemical composition and catalytic activity on oxidative stress. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:4158–4163. doi: 10.1021/es062629t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teeguarden JG. Hinderliter PM. Orr G. Thrall BD. Pounds JG. Particokinetics in vitro: dosimetry considerations for in vitro nanoparticle toxicity assessments. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:300–312. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z. Meng H. Xing G. Chen C. Zhao Y. Jia G. Wang T. Yuan H. Ye C. Zhao F. Chai Z. Zhu C. Fang X. Ma B. Wan L. Acute toxicological effects of copper nanoparticles in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 2006;163:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng H. Chen Z. Xing G. Yuan H. Chen C. Zhao F. Zhang C. Zhao Y. Ultrahigh reactivity provokes nanotoxicity: explanation of oral toxicity of nano-copper particles. Toxicol Lett. 2007;175:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prabhu B. Ali SF. Murdock RC. Hussain SM. Srivatsan M. Copper nanoparticles exert size and concentration dependent toxicity on somatosensory neurons of rat. Nanotoxicology. 2010;4:150–160. doi: 10.3109/17435390903337693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]