Abstract

To date, the utility of single genetic markers to improve disease risk assessment still explains only a small proportion of genetic variance for many complex diseases. This missing heritability may be explained by additional variants with weak effects. To discover and incorporate these additional genetic factors, statistical and computational methods must be evaluated and developed. We develop a multi-locus genetic risk score (GRS) based approach to analyze genes in NADPH oxidase complex which may result in susceptibility to development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We find the complex is highly associated with IBD (P = 7.86 × 10−14) using the GRS-based association method. Similar results are also shown in permutation analysis (P = 6.65 × 10−11). Likelihood ratio test shows that the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the complex without nominal signals have significant contribution to the overall genetic effect within the complex (P = 0.015). Our results show that the multi-locus GRS association model can improve the genetic risk assessment on IBD by taking into account both confirmed and as yet unconfirmed disease susceptibility variants.

Keywords: genetic risk score, inflammatory bowel disease, permutation analysis, association analysis

Background

In the past few years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been widely used to identify genetic risk factors for complex diseases. This analysis paradigm has made significant progress in many genetic studies. For example, many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been discovered thus far to be associated with several common diseases, such as type 2 diabetes.1,2 However, single genetic markers still explain only a small proportion of the genetic variance for many complex diseases. It is expected that this missing heritability may be explained by additional rare variants with strong effects and/or common variants with weak effects.3 To discover and combine these additional genetic factors, statistical methods for the detection of associations of common variants have been extensively developed and successively applied to numerous studies of complex traits. For example, the use of a multi-locus genetic risk score (GRS) has been proposed to evaluate risk of breast cancer and its subtypes4 and prostate cancer.5 Pathway-based analysis strategy has also been used to search for related genes and SNPs contributing to basal cell carcinoma of the skin6 by joint effect analysis of the genes or SNPs in a given pathway. Some recent studies5,7 have been developed to integrate these two analysis strategies. However, Tintle et al7 show that when aggregation methods (one type of GRS-based approaches) are applied to analyze variants from sequencing data at the pathway level, a common problem is that there is a high Inflated type I error rate. Therefore, the inflated type I error in the framework of GRS-based pathway association analysis, a joint strategy of GRS-based associated analysis, and pathway-based association analysis should be evaluated in detail.

Genetic association studies have identified innate immunity as a critical component in the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).8–12 However, these studies have identified only 23% of the susceptibility determinants for Crohn’s disease (CD) and 16% for ulcerative colitis (UC).10–12

A recent study has provided insight into the role of NADPH oxidase complex in the development of IBD.13 It has shown that genetic mutations in genes encoding components of the complex result in both X-linked and autosomal recessive forms of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). Patients with CGD often develop intestinal inflammation that is histologically similar to Crohn’s colitis, suggesting a common etiology for both diseases. Here we undertake a candidate gene study to determine if components of the NADPH oxidase complex are associated with IBD. We report associations of NADPH oxidase autosomal genes CYBA, NCF2, NCF4, and RAC2 with IBD.14 To this end, we use a multi-locus GRS-based approach to evaluate the joint effect of the genetic components of the NADPH oxidase complex on IBD. We apply a permutation test to assess inflated type I error of GRS-based complex association analysis model.

Materials and Methods

Data set

Tag SNPs are selected based on Caucasian (CEU) phase II data Release 23a of International HapMap project (http://www.hapmap.org). A total of 60 tag SNPs (r2 > 0.8) are chosen which span the NADPH oxidase complex genes RAC2 (19 SNPs), CYBA (5 SNPs), NCF2 (15 SNPs), and NCF4 (21 SNPs). Genotyping of samples are performed using the Illumina® Goldengate Custom Chip genotyping system at The Centre for Applied Genomics, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

The data set includes a total of 2049 individuals of European descent. 1200 of these have IBD (656 with CD and 544 with UC) while the other 849 are healthy controls (HC) (Table 1). Our IBD patients are recruited from the Hospital for Sick Children (22%) and Mount Sinai Hospital (78%) in Toronto, as well as locally and from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Study subject phenotypic information and DNA samples were obtained with institutional review ethics board approval for IBD genetic studies at the Hospital for Sick Children and Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. These individuals are those who passed quality control in the Muise et al study.14

Table 1.

Number of samples in IBD, its subtypes CD and UC and healthy controls.

| Diseases | Number of samples | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Cases | Healthy controls | |

| IBD | ||

| All samples | 1200 | 849 |

| Female samples | 606 | 538 |

| Male samples | 594 | 311 |

| CD | ||

| All samples | 656 | 849 |

| Female samples | 312 | 538 |

| Male samples | 344 | 311 |

| UC | ||

| All samples | 544 | 849 |

| Female samples | 294 | 538 |

| Male samples | 250 | 311 |

Univariate SNP association analysis

Univariate SNP analysis is performed to detect the associations of the SNPs in the four genes involved in the NADPH oxidase complex (RAC2, CYBA, NCF2, and NCF4) between IBD and HC. For each individual i, i = 1, …, 2049, we define disease status as outcome:

| (1) |

Each SNP is coded as 0, 1, or 2 corresponding to genotypes containing 0, 1, or 2 minor alleles, respectively. We perform logistic regression analysis to test association between IBD and HC as follows:

| (2) |

where Gi = 0, 1, or 2 minor alleles for a given genotype and Genderi for an individual i. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are estimated for each SNP j. The association analysis is also performed for IBD’s subtypes CD and UC, respectively. We also performed subgroup analysis without adjusting gender for male samples only and female samples only, separately. The analyses are performed using PLINK version 1.0615 and SAS 9.2.

Weighted genetic risk score based association analysis

We calculated GRS for each individual as a weighted sum of risk alleles for each SNP in the NADPH oxidase complex.4 The weight is the estimated effect size (OR) of each SNP j. These scores are summed into a multi-locus GRS for each individual i. Specifically, the individual specific GRS for the complex is given as:

| (3) |

where i = 1, …, n individuals and j = 1, …, k SNPs in a given complex. Gi = 0, 1, or 2 minor alleles for a given genotype as defined in Formula 2, ORj is estimated from Formula 2 and equals to exp (βcirc;); sign(ORj) is 1 if ORj > 1, and −1 otherwise. We applied logistic regression model to evaluate the genetic association between the GRS of the complex and IBD as follows:

| (4) |

The GRS-based association analysis is also performed for IBD’s subtypes CD and UC, respectively. We also performed subgroup analysis without adjusting gender for only male and female samples, separately.

Permutation analysis

Since the multi-locus GRS in our model is constructed using the linear combination of the genetic risk alleles, weighted by their genetic effects that are estimated from the univariate models, similar to the multivariate regression model using multiple predictors, the linear combination of such effects may over fit the data and cause inflated type I error.

To avoid such inflated type I error, an honest estimation of the null distribution of the GRS test statistics is critical. We used the permutation test to estimate the null distribution of the test statistics from our GRS model.16 Because the data sets are permuted, the SNP genotypes are independent to the permuted disease status. Using large number of permuted data sets, the empirical distribution of the test statistics of the GRS model on the permuted data sets is used as the empirical null distribution of the test statistics of the GRS model.

More specifically, we randomly permuted IBD and HC sample labels 1000 times. For each permutated data set, we recalculated the GRS and performed association analysis as described in Section of weighted genetic risk score based association analysis. Since the test statistic (on βGRS) of the permuted data set is under the null hypothesis of no association, it follows an asymptotically normally distribution (P > 0.05 based on one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

The empirical null distribution of test statistics in the GRS-based association analysis was then estimated based on the 1000 permutation results. The test statistic of the real data was then compared to such empirical null distribution to estimate the empirical P-values.

Likelihood ratio test

Since some of the SNPs used in the complex analysis show nominal signals (P < 0.05) at univariate SNP association analysis, to evaluate the additional genetic effect due to SNPs without association, a likelihood ratio test was applied to compare the logistic regression-based association model on genetic risk score constructed using all the SNPs (full model) and the model on genetic risk score using only SNPs with nominal signals (reduced model).17 Since these two models are nested, the likelihood ratio test was performed to assess if the non-nominal SNPs contribute to the overall genetic effect within the complex.

Results

Univariate SNP association analysis

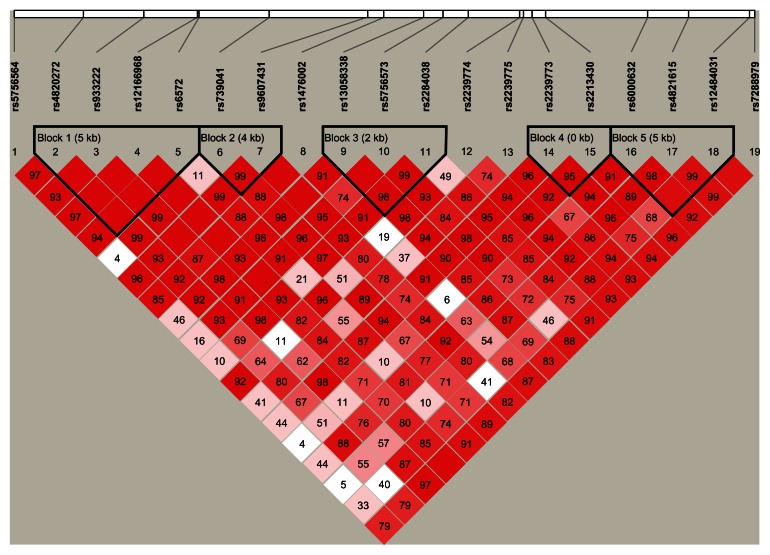

56 of the 60 tag SNPs pass the quality control (QC). They have minor allele frequency (MAF) larger than 1%, call rate larger than 95%, and P-value of Hardy- Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) test larger than 1 × 10−5 in control. The 2049 subjects used in the study have a genotype call rate larger than 95%. We examined the association of the 56 genotyped SNPs with IBD and its subtypes (CD and UC) as compared to the control group, respectively. There were 16, 14, and 10 of the 56 SNPs with nominal P-value smaller than 0.05 for IBD and its subtypes (CD and UC), respectively. Among these, 5, 8, and 1 of the 16, 14, and 10 SNPs are statistically significant after Bonferroni correction (unadjusted P-value at 8.6 × 10−4 level) for IBD and its subtypes (CD and UC), respectively (Table 2). Majority of these significant SNPs are in gene RAC2 region. The remaining SNPs are not significantly associated with the disease status. The association results for all 56 SNPs are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–3. We obtained linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns of all 19 tag SNPs in the gene RAC2 using Haploview (Fig. 1).18 As shown in Figure 1, the significant SNPs are located in different LD blocks. We also performed the association analyses for female samples only and male samples only, respectively.

Table 2.

SNPs show significant association with IBD and its subtypes CD and UC.

| Chr | SNP | Base pair | All samples | Female samples | Male samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| OR (95% CI)* | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| IBD | ||||||||

| 16 | rs2066845 | 49314041 | 2.34 (1.56–3.56) | 4.87E-05 | 2.91 (1.65–5.12) | 0.0002 | 1.80 (0.99–3.28) | 0.054 |

| 22 | rs6572 | 35951391 | 1.31 (1.15–1.49) | 4.90E-05 | 1.30 (1.10–1.54) | 0.0022 | 1.31 (1.07–1.60) | 0.008 |

| 22 | rs9607431 | 35959884 | 1.48 (1.22–1.79) | 5.39E-05 | 1.37 (1.07–1.77) | 0.013 | 1.63 (1.22–2.19) | 0.001 |

| 22 | rs2239773 | 35968235 | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | 0.00039 | 0.73 (0.60–0.90) | 0.0028 | 0.79 (0.63–1.00) | 0.049 |

| 22 | rs2239774 | 35967599 | 1.35 (1.14–1.61) | 0.00064 | 1.35 (1.07–1.70) | 0.010 | 1.35 (1.04–1.76) | 0.025 |

| CD | ||||||||

| 16 | rs2066845 | 49314041 | 3.51 (2.27–5.42) | 1.48E-08 | 4.47 (2.46–8.12) | 9E-07 | 2.63 (1.42–4.87) | 0.002 |

| 2 | rs10210302 | 233823578 | 0.72 (0.62–0.84) | 1.82E-05 | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) | 0.018 | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | 0.0002 |

| 22 | rs9607431 | 35959884 | 1.59 (1.29–1.97) | 2.00E-05 | 1.49 (1.12–2.00) | 0.0067 | 1.72 (1.25–2.36) | 0.0009 |

| 2 | rs2241880 | 233848107 | 0.72 (0.62–0.84) | 2.15E-05 | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) | 0.018 | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | 0.0002 |

| 22 | rs2239774 | 35967599 | 1.49 (1.22–1.81) | 6.91E-05 | 1.49 (1.14–1.95) | 0.0034 | 1.48 (1.11–1.97) | 0.007 |

| 22 | rs6572 | 35951391 | 1.34 (1.16–1.56) | 0.00011 | 1.34 (1.09–1.64) | 0.0053 | 1.36 (1.09–1.69) | 0.007 |

| 16 | rs2066844 | 49303427 | 1.73 (1.30–2.31) | 0.00019 | 1.63 (1.11–2.40) | 0.012 | 1.87 (1.20–2.90) | 0.005 |

| 22 | rs2239773 | 35968235 | 0.74 (0.61–0.88) | 0.00083 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | 0.0035 | 0.79 (0.61–1.03) | 0.076 |

| UC | ||||||||

| 22 | rs746713 | 35589305 | 0.73 (0.61–0.86) | 0.00030 | 0.72 (0.58–0.91) | 0.0054 | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) | 0.021 |

Notes: The table includes results of association analysis between genotypes and IBD as well as its subtypes CD and UC based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. These SNPs are significant at Bonferroni corrected P-value 0.05 level (Unadjusted P-value at 8.6E-04) for the results based on all samples. In the association analysis, we also adjust gender.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

LD plot of the 19 SNPs in RAC2 gene.

Notes: LD plot showing LD patterns among the 19 SNPs in RAC2 gene genotyped in the 2049 samples. The LD between the SNPs is measured as r2 and shown (×100) in the diamond at the intersection of the diagonals from each SNP. r2 = 0 is shown as white, 0 < r2 < 1 is shown in pink and r2 = 1 is shown in red. The analysis track at the top shows the SNPs according to chromosomal location. Five haplotype blocks (outlined in bold black line) indicating markers that are in high LD are shown.

We observe there is only 1 significant SNP (rs2066845) associated with IBD and its subtype CD in female samples, and 2 SNPs (rs10210302 and rs2241880) associated with CD in male samples (Table 2 and Supplementary Tables 1–3).

A multi-locus GRS-based association analysis

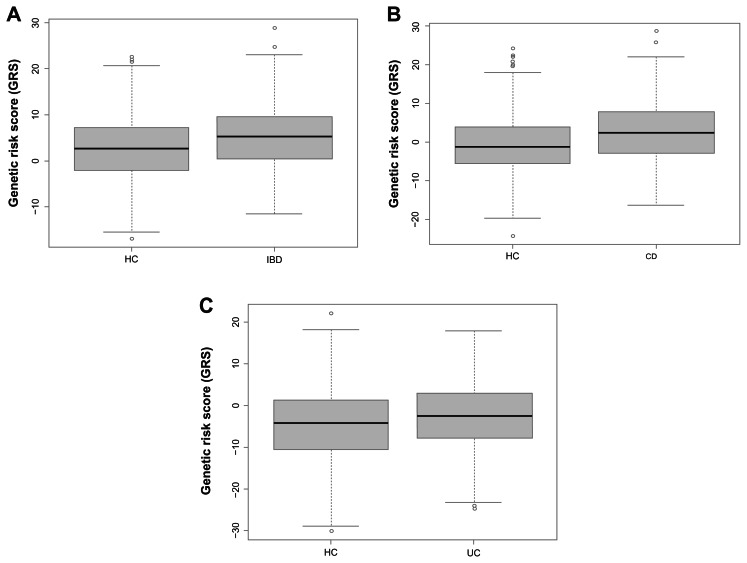

We next examined the role of all genotyped SNPs in NADPH oxidase complex in the pathogenesis of IBD and its subtypes CD and UC using the GRS analysis. All 56 genotyped RAC2, CYBA, NCF2, and NCF4 SNPs are used. We found a significant association between GRS and IBD and its subtypes CD and UC (Table 3), respectively. Gender is also significantly associated with IBD and its subtypes CD and UC (Table 3), separately. Furthermore, we performed the analysis for male and female samples independently, as shown in Table 3. GRS still has significant association with IBD and its subtypes CD and UC, respectively, although the P value is slightly larger. The boxplots of the GRS estimated from IBD versus HC, and its subtypes CD versus HC, and UC versus HC, are shown in Figure 2 (all sample case). It is clear that the IBD group have a larger genetic risk than HC group as patients with IBD have a mean weighted GRS of 5.11 (standard error (SE): 0.19) while controls have a mean GRS of 2.75 (SE: 0.24). Patients with IBD’s subtype CD have a mean weighted GRS of 2.59 (SE: 0.30) while controls have a mean GRS of −0.70 (SE: 0.25). Similarly, patients with IBD’s subtype UC have a mean weighted GRS of −0.24 (SE: 0.34) while controls have a mean GRS of −4.57 (SE: 0.29). The P-values of t-test (two-sided) to evaluate the mean differences between diseases (IBD, and its subtypes CD and UC) and HC are P = 2.67 × 10−14, P < 2.2 × 10−16, P = 0.001, respectively.

Table 3.

Association analysis between GRS and IBD and its subtype CD and UC.

| Diseases | GRS | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR | P value | |

| IBD | ||||

| All samples | 1.66 (1.46–1.90) | 7.86E-14 | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | 1.31E-08 |

| Female samples | 1.43 (1.25–1.64) | 2.08E-07 | – | – |

| Male samples | 2.08 (1.68–2.60) | 4.57E-11 | – | – |

| CD | ||||

| All samples | 1.82 (1.57–2.11) | 7.85E-16 | 0.53 (0.43–0.65) | 4.07E-09 |

| Female samples | 1.68 (1.41–2.00) | 8.15E-09 | – | – |

| Male samples | 2.04 (1.67–2.51) | 9.86E-12 | – | – |

| UC | ||||

| All samples | 1.37 (1.20–1.57) | 2.74E-06 | 0.68 (0.55–0.85) | 6.1E-4 |

| Female samples | 1.51 (1.26–1.81) | 9.76E-06 | – | – |

| Male samples | 1.66 (1.32–2.11) | 1.63E-05 | – | – |

Figure 2.

Boxplots of genetic risk score analysis. Boxplots of IBD versus HC (A), CD versus HC (B), and UC versus HC (C).

Notes: GRS analysis is performed using 56 SNPs in RAC1/2, CYBA, NCF2, and NCF4 genes. SNPs are weighted based on the effect size (OR) from the univariate SNP association analysis by adjusting on gender.

We applied a permutation test on the genetic risk score for the complex analysis to adjust for inflated type I error. 1000 permutations were performed by randomly assigning the case and control status (IBD versus HC, CD versus HC, and UC versus HC) (all sample case as defined in Table 3). The estimated empirical P-values for IBD versus HC, CD versus HC, and UC versus HC are P = 6.65 × 10−11, P = 8.22 × 10−13, P = 9.22 × 10−4, respectively. The P-values are calculated as follows (taking IBD versus HC as an example): First we applied our GRS model to each of the permuted data set. The test statistics of the permuted GRS models were used to estimate the null distribution. We estimated mean and standard deviation (sd) of the test statistic values in the permutated data, 0.051 and 1.21, respectively, then performed one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to evaluate the null hypothesis that the true distribution of the test statistic values is not less than or not greater than the hypothesized normal distribution N (0.051, 1.21). Our result shows the P-value is not significant, therefore the null distribution follows normal distribution. This is also indicated by the skewness of 0.05 and the kurtosis of 2.84. Therefore, The estimated empirical P-value of the observed test statistic value from the standard logistic regression analysis were calculated based on the hypothesized normal distribution N (0.051, 1.21) when comparing IBD with HC.

Although some SNPs used in the complex analysis showed nominal signals (P < 0.05), we evaluated the additional genetic effect due to SNPs without association. The likelihood ratio test was performed to compare the model of genetic risk score constructed using all genotyped SNPs and the model of genetic risk score using only SNPs with nominal signals. Our analysis shows these two models are significantly different, suggesting the SNPs without nominal signals have a significant additional contribution to the overall genetic effect within the complex when IBD versus HC and its subtypes CD versus HC, and UC versus HC (P = 0.015, P = 0.003, and P = 0.023, respectively) are compared. This analysis demonstrates that focusing on genetic complexes as opposed to individual SNPs is important and critical for understanding the genetic heritability in IBD.

Discussion and Conclusions

A key problem in genetic and genomic research is to identify genes and complexes that are involved in diseases and other biological processes. Many statistical and computational methods have been developed for identifying genes in a regression framework. The identified genes are often linked to known biological complexes. However, most of the procedures for identifying the biologically relevant genes do not utilize the known complex information. Here we focus on the genes in a candidate complex (NADPH oxidase complex) which are shown to play a key role in the development of IBD. When compared to univariate SNP-based association analysis, the multi-locus GRS-based complex association model is very successful at evaluating the association between IBD and its candidate complex by taking into account both confirmed and as yet unconfirmed disease susceptibility variants. Our GRS-based complex results show that the complex has quite significant association with IBD and its subtypes CD and UC. The significant association of the complex with IBD and its subtypes are also observed (P < 0.05) when we use an unweighted multi-locus GRS strategy, in which the identity weight is applied for each marker (results not shown).

We applied GRS framework weighted on the OR estimated from the univariate analysis. The advantages of this approach are that ORs have clearer clinical meaning and are more straightforward for interpretation than other weighting strategies. For example, weighting can be based on regression coefficient4 or identical weight.19 We also applied other weighting strategies, such as using the regression coefficients as weights or identical weights to our data. These different weighting strategies provide consistent significant signals (results not shown).

In the genetic association analysis, the statistical significance is driven by both effect size and sample size. If work on the genetic markers is done one by one, some of the genetic markers with moderate genetic effects may not be powerful enough to show nominal signals. However, such moderate effects can be accumulated at the complex level analysis. Therefore, the GRS-pathway approach can potentially improve statistical power.

Recent studies (eg, Tintle et al7) show when aggregation methods (a type of GRS-based approaches) are applied to analyze variants from sequencing data at pathway level, a common problem is that there is a high Inflated type I error rate. In our study, we applied the permutation approach to potentially correct this error as permutation procedures can generate an empirical null distribution and estimate the empirical P-value. This approach has desirable properties including its ability to relax assumptions about normality of continuous phenotypes and Hardy- Weinberg equilibrium, dealing with rare alleles and small sample sizes.

It must be admitted that our current findings are based on a single study and further investigation is still warranted to generalize the conclusions by applying the approaches to other studies and to validate whether the findings can be replicated. Although our GRS-based complex association approach can be applied to either a single or multiple pre-defined complexes, there is a limitation to apply it to a large complex with many SNPs or a complex with a few significant SNPs but many NULL SNPs. In this case, we suggest including only SNPs with suggestive association, as done by Reeves et al,4 in which only 14 disease associated SNPs are included in estimating GRS.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Table 1: Univariate association analysis results on IBD.

The table includes association analysis results on IBD based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. For the results based on all samples, gender has been adjusted as covariate.

Supplementary Table 2: Univariate association analysis results on CD.

The table includes association analysis results on CD based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. For the results based on all samples, gender has been adjusted as covariate.

Supplementary Table 3: Univariate association analysis results on UC.

The table includes association analysis results on UC based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. For the results based on all samples, gender has been adjusted as covariate.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: WX, PH, AMM, JHB, MSS. Analyzed the data: PH, WX, XX. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: PH, WX. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: PH, WX, AMM. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: WX, PH, AMM, XX, JHB, MSS. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

All authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

Funding

PH is supported by Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute. AMM is supported by an Early Researcher Award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation. JHB. is the recipient of an Investigators of Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. This work was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to AMM (MOP119457) and JHB (MOP97756). Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01DK062423. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the NIDDK IBD Genetics Consortium for providing control samples. They also acknowledge the work of Joanne Stempak at Mount Sinai.

References

- 1.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):638–45. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42(7):579–89. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu P, Xu W, Chen L, Xing X, Paterson AD. Pathway-based joint effects analysis of rare genetic variants using Genetic Analysis Workshop 17 exon sequence data. BMC Proc. 2011;5(Suppl 9):S45. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S9-S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeves GK, Travis RC, Green J, et al. Incidence of breast cancer and its subtypes in relation to individual and multiple low-penetrance genetic susceptibility loci. JAMA. 2010;304(4):426–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro RJT, Monteiro CPD, Azevedo ASM, Cunha VFM, Ramanakumar AV, et al. Performance of an adipokine pathway-based multilocus genetic risk score for prostate cancer risk prediction. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M, Liang L, Xu M, Qureshi AA, Han J. Pathway analysis for genome-wide association study of basal cell carcinoma of the skin. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tintle N, Aschard H, Hu I, Nock N, Wang H, Pugh E. Inflated type I error rates when using aggregation methods to analyze rare variants in the 1000 Genomes Project exon sequencing data in unrelated individuals: summary results from Group 7 at Genetic Analysis Workshop 17. Genet epidemiol. 2011;35(Suppl 1):S56–60. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith AM, Rahman FZ, Hayee B, et al. Disordered macrophage cytokine secretion underlies impaired acute inflammation and bacterial clearance in Crohn’s disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1883–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstiel P, et al. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet. 2007;39(2):207–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):596–604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villani AC, Lemire M, Fortin G, et al. Common variants in the NLRP3 region contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):71–6. doi: 10.1038/ng285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):830–2. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meissner F, Seger RA, Moshous D, Fischer A, Reichenbach J, Zychlinsky A. Inflammasome activation in NADPH oxidase defective mononuclear phagocytes from patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Blood. 2010;116(9):1570–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muise AM, Xu W, Guo CH, et al. NADPH oxidase complex and IBD candidate gene studies: identification of a rare variant in NCF2 that results in reduced binding to RAC2. Gut. 2012;61(7):1028–35. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good P. Permutation Tests. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilks SS. The large-sample distribution of the likelihood ratio for testing composite hypotheses. Ann Math Statist. 1938;9(1):60–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Jatkoe T, Zhang Y, et al. Gene expression profiles and molecular markers to predict recurrence of Dukes’ B colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1564–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Univariate association analysis results on IBD.

The table includes association analysis results on IBD based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. For the results based on all samples, gender has been adjusted as covariate.

Supplementary Table 2: Univariate association analysis results on CD.

The table includes association analysis results on CD based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. For the results based on all samples, gender has been adjusted as covariate.

Supplementary Table 3: Univariate association analysis results on UC.

The table includes association analysis results on UC based on all samples, female samples only and male samples only, respectively. For the results based on all samples, gender has been adjusted as covariate.