Abstract

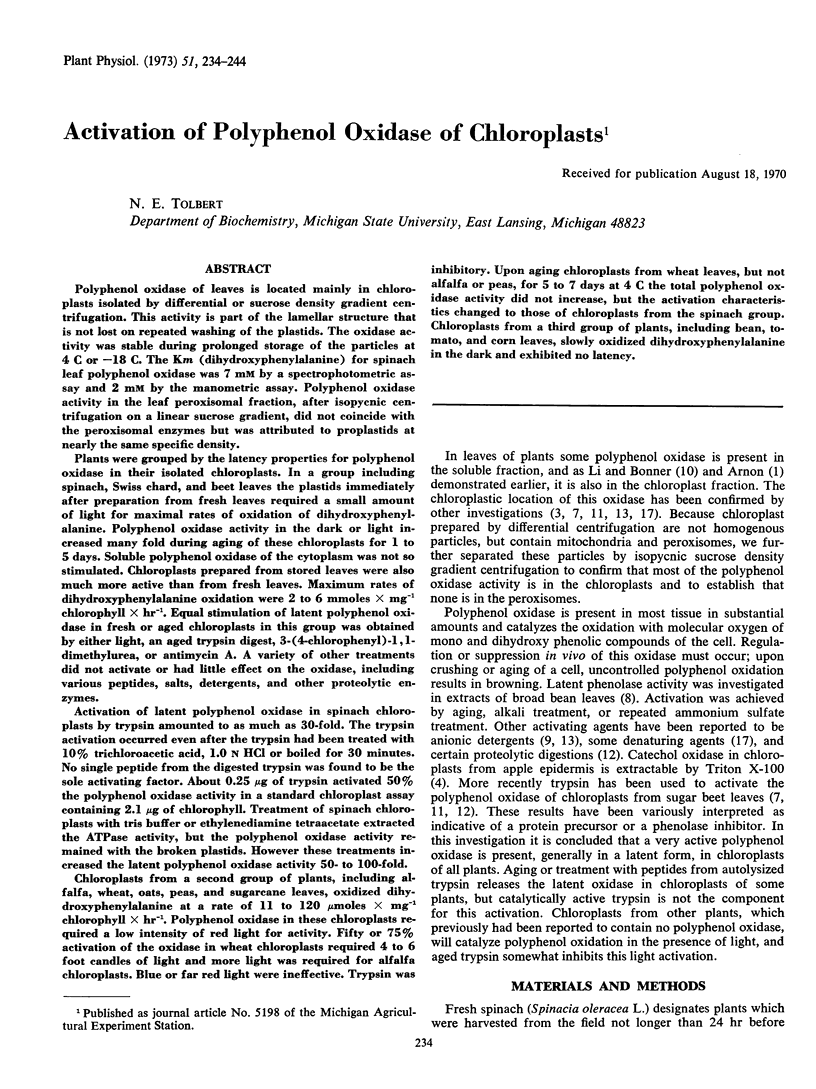

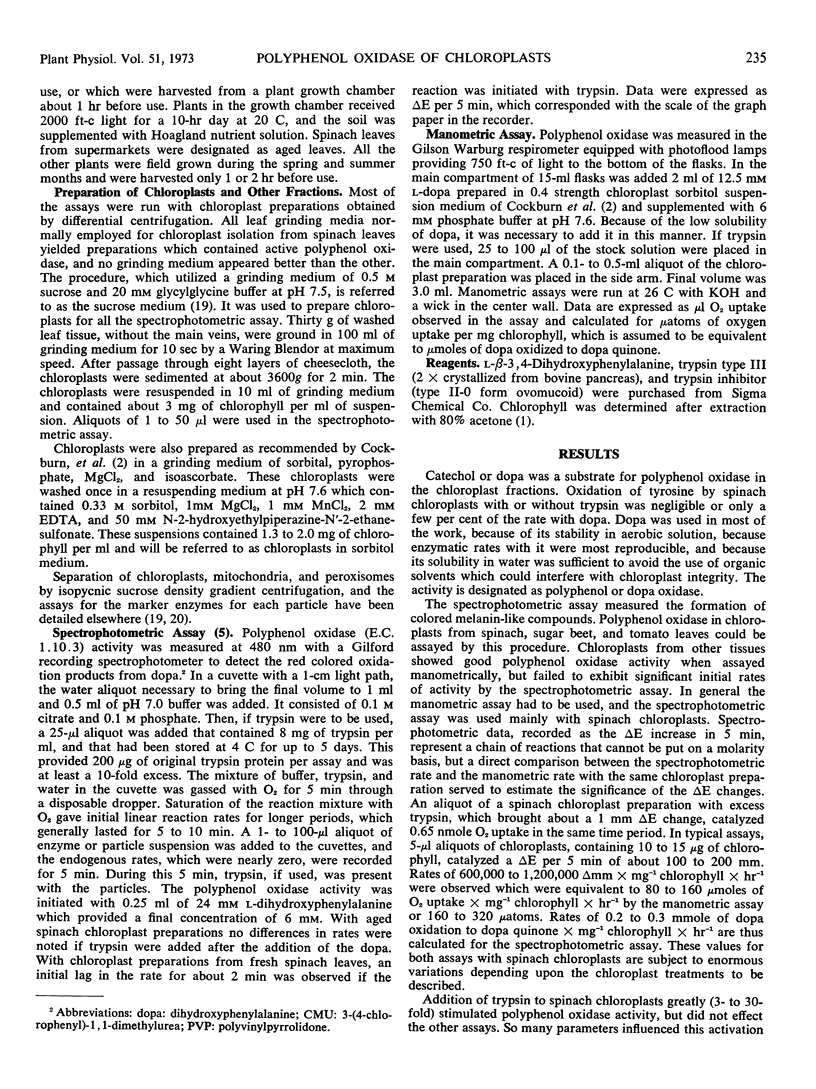

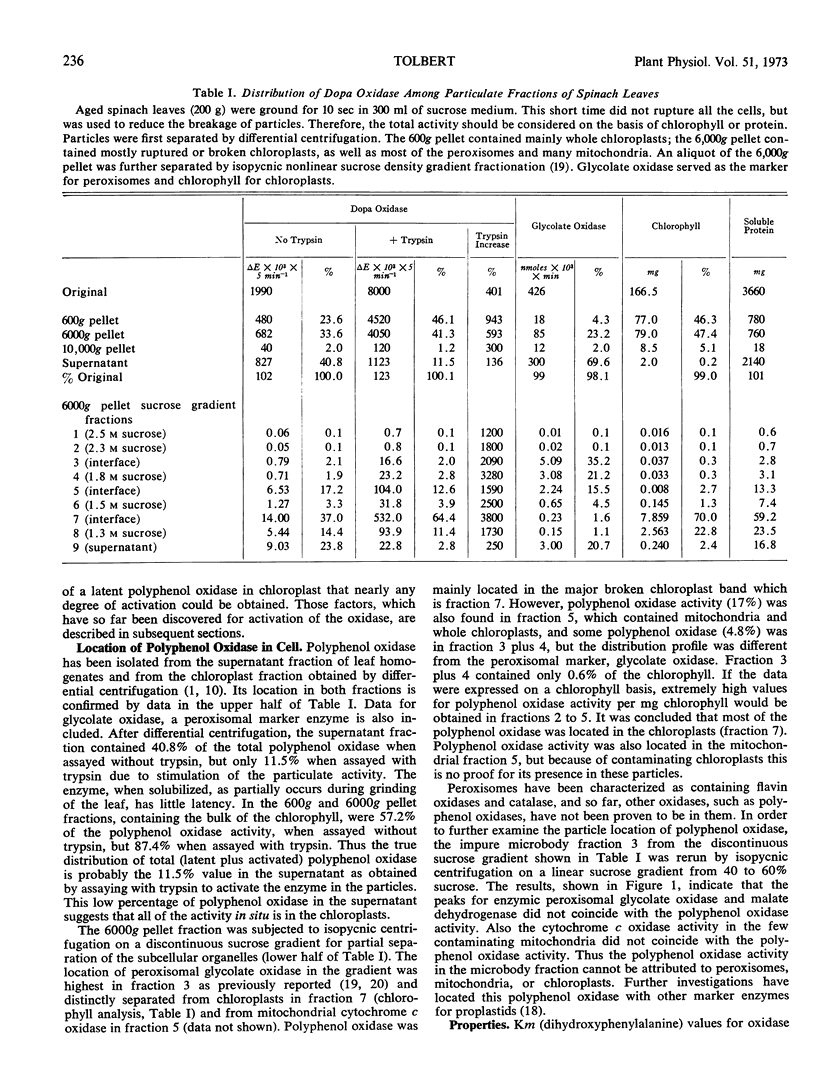

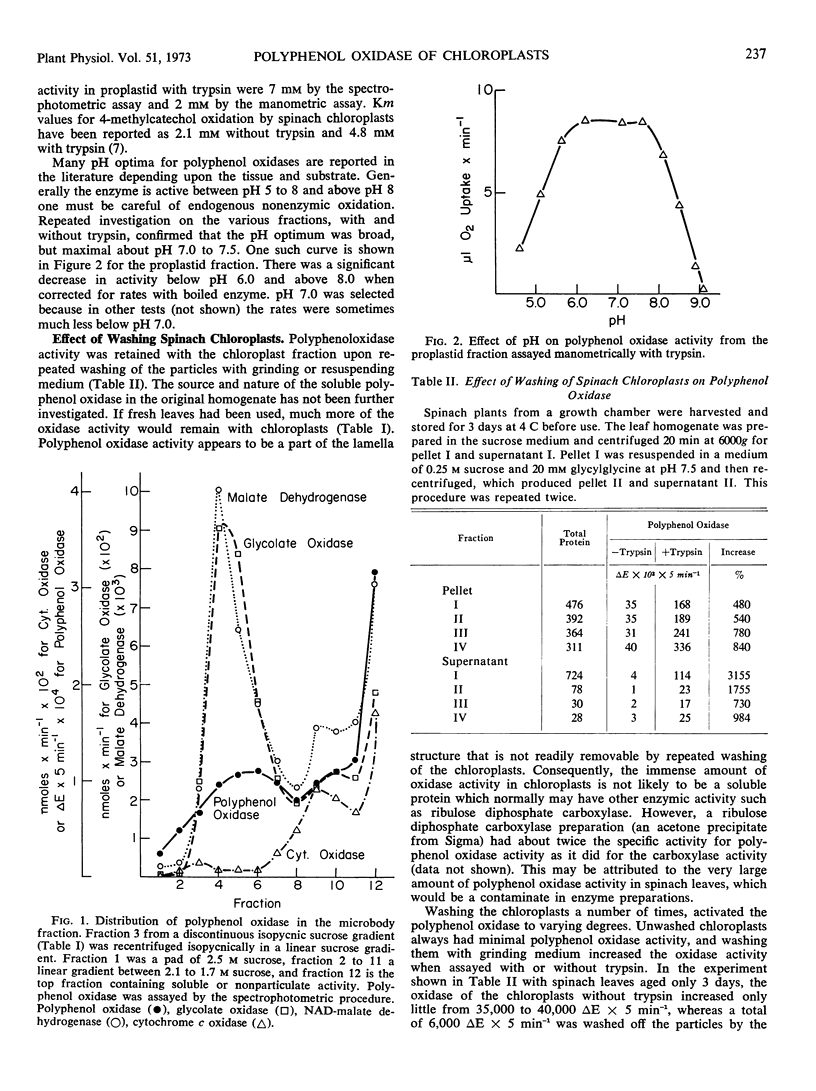

Polyphenol oxidase of leaves is located mainly in chloroplasts isolated by differential or sucrose density gradient centrifugation. This activity is part of the lamellar structure that is not lost on repeated washing of the plastids. The oxidase activity was stable during prolonged storage of the particles at 4 C or —18 C. The Km (dihydroxyphenylalanine) for spinach leaf polyphenol oxidase was 7 mm by a spectrophotometric assay and 2 mm by the manometric assay. Polyphenol oxidase activity in the leaf peroxisomal fraction, after isopycnic centrifugation on a linear sucrose gradient, did not coincide with the peroxisomal enzymes but was attributed to proplastids at nearly the same specific density.

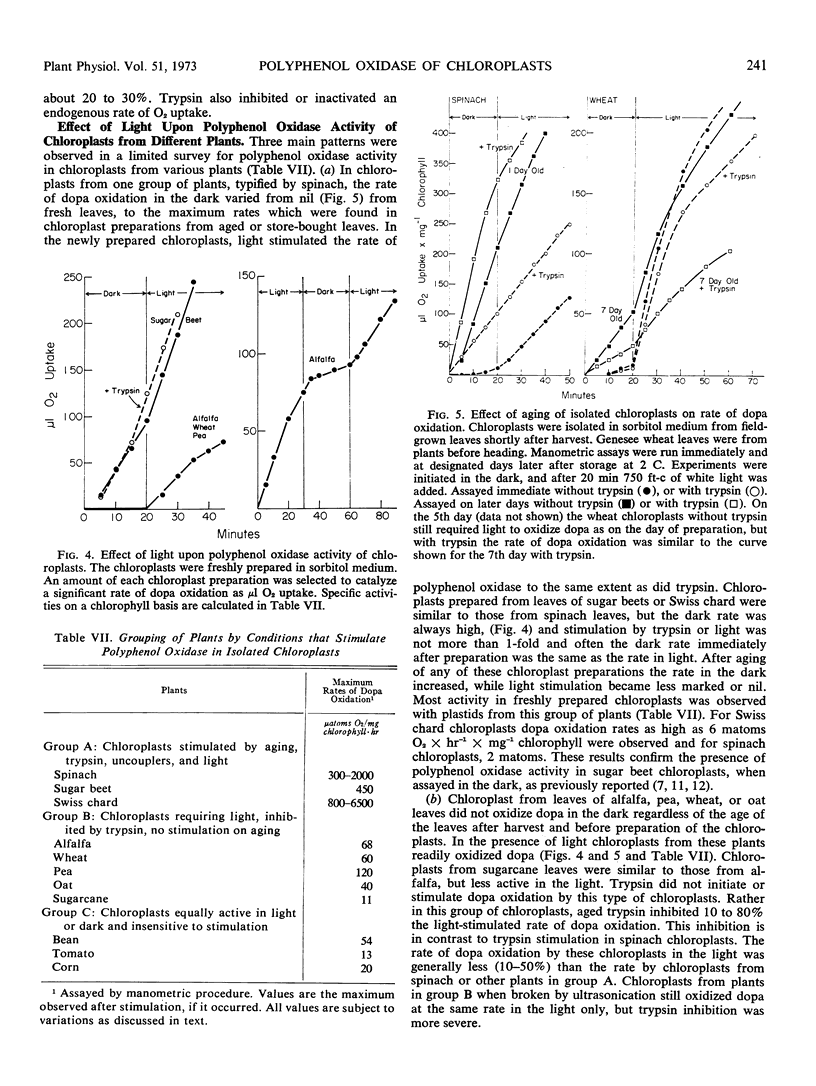

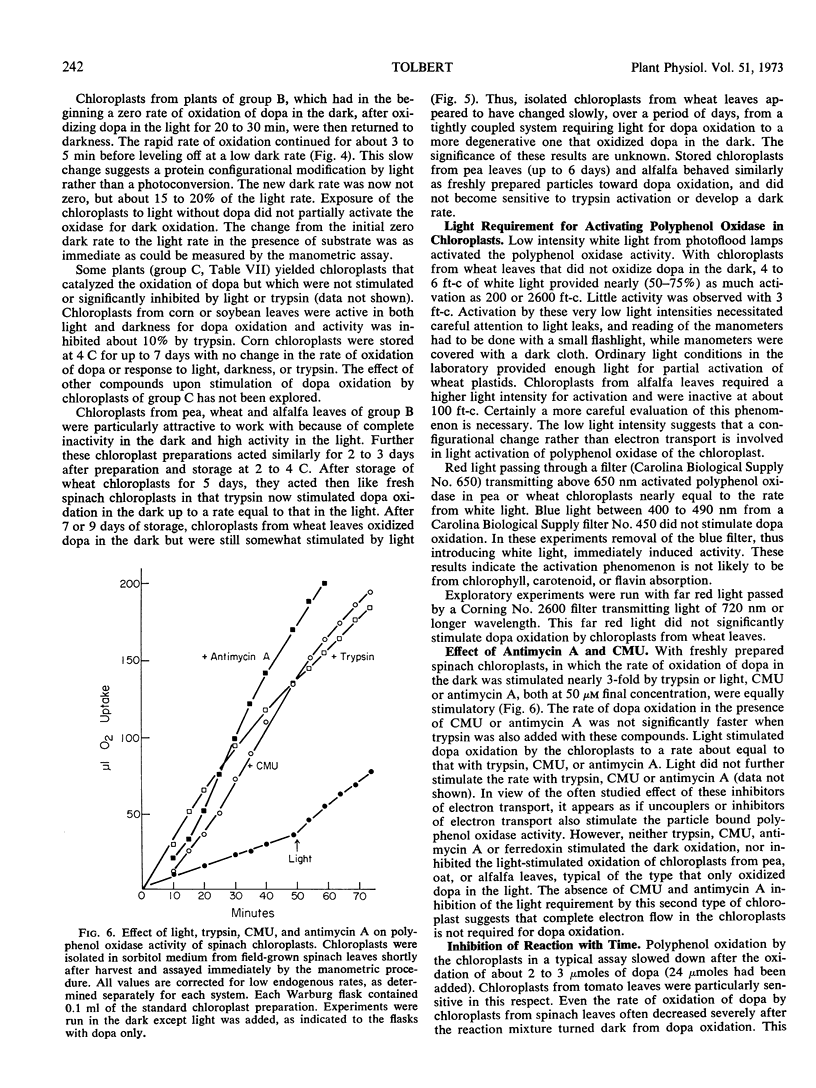

Plants were grouped by the latency properties for polyphenol oxidase in their isolated chloroplasts. In a group including spinach, Swiss chard, and beet leaves the plastids immediately after preparation from fresh leaves required a small amount of light for maximal rates of oxidation of dihydroxyphenylalanine. Polyphenol oxidase activity in the dark or light increased many fold during aging of these chloroplasts for 1 to 5 days. Soluble polyphenol oxidase of the cytoplasm was not so stimulated. Chloroplasts prepared from stored leaves were also much more active than from fresh leaves. Maximum rates of dihydroxyphenylalanine oxidation were 2 to 6 mmoles × mg−1 chlorophyll × hr−1. Equal stimulation of latent polyphenol oxidase in fresh or aged chloroplasts in this group was obtained by either light, an aged trypsin digest, 3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1, 1-dimethylurea, or antimycin A. A variety of other treatments did not activate or had little effect on the oxidase, including various peptides, salts, detergents, and other proteolytic enzymes.

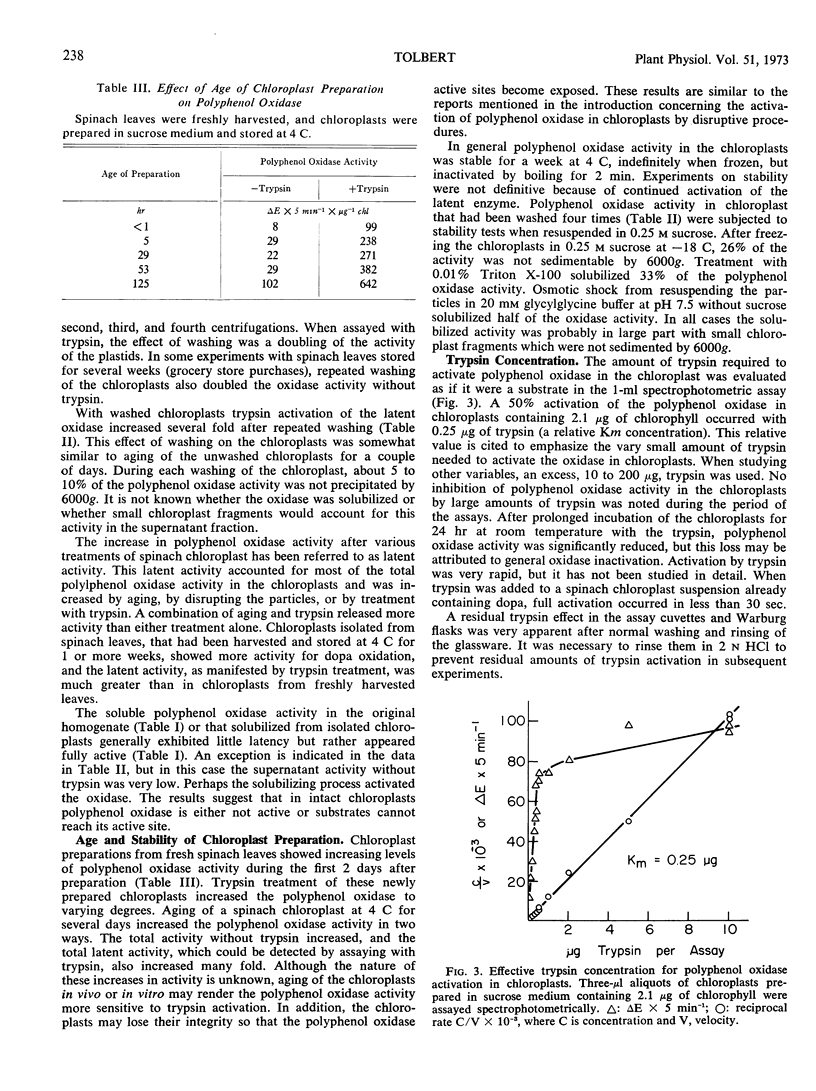

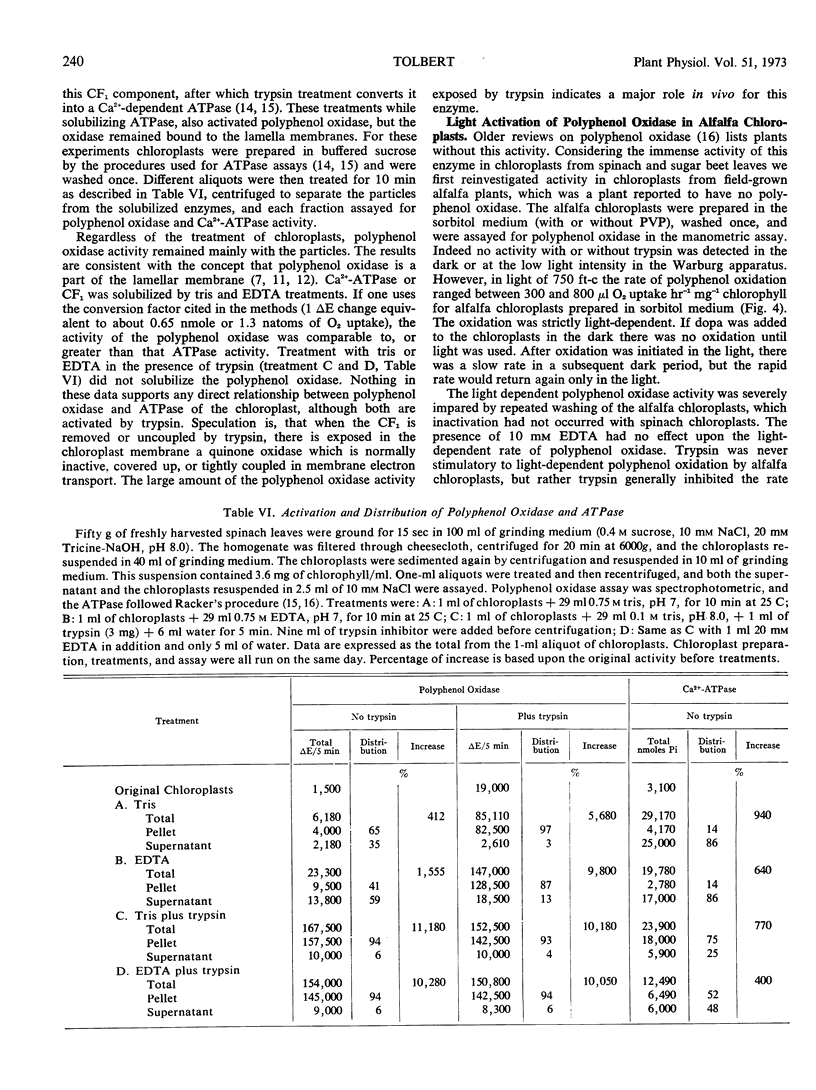

Activation of latent polyphenol oxidase in spinach chloroplasts by trypsin amounted to as much as 30-fold. The trypsin activation occurred even after the trypsin had been treated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, 1.0 n HCl or boiled for 30 minutes. No single peptide from the digested trypsin was found to be the sole activating factor. About 0.25 μg of trypsin activated 50% the polyphenol oxidase activity in a standard chloroplast assay containing 2.1 μg of chlorophyll. Treatment of spinach chloroplasts with tris buffer or ethylenediamine tetraacetate extracted the ATPase activity, but the polyphenol oxidase activity remained with the broken plastids. However these treatments increased the latent polyphenol oxidase activity 50- to 100-fold.

Chloroplasts from a second group of plants, including alfalfa, wheat, oats, peas, and sugarcane leaves, oxidized dihydroxyphenylalanine at a rate of 11 to 120 μmoles × mg−1 chlorophyll × hr−1. Polyphenol oxidase in these chloroplasts required a low intensity of red light for activity. Fifty or 75% activation of the oxidase in wheat chloroplasts required 4 to 6 foot candles of light and more light was required for alfalfa chloroplasts. Blue or far red light were ineffective. Trypsin was inhibitory. Upon aging chloroplasts from wheat leaves, but not alfalfa or peas, for 5 to 7 days at 4 C the total polyphenol oxidase activity did not increase, but the activation characteristics changed to those of chloroplasts from the spinach group. Chloroplasts from a third group of plants, including bean, tomato, and corn leaves, slowly oxidized dihydroxyphenylalanine in the dark and exhibited no latency.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arnon D. I. COPPER ENZYMES IN ISOLATED CHLOROPLASTS. POLYPHENOLOXIDASE IN BETA VULGARIS. Plant Physiol. 1949 Jan;24(1):1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn W., Walker D. A., Baldry C. W. The isolation of spinach chloroplasts in pyrophosphate media. Plant Physiol. 1968 Sep;43(9):1415–1418. doi: 10.1104/pp.43.9.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOROWITZ N. H., SHEN S. C. Neurospora tyrosinase. J Biol Chem. 1952 May;197(2):513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATOH S., SUGA I., SHIRATORI I., TAKAMIYA A. Distribution of plastocyanin in plants, with special reference to its localization in chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961 Jul;94:136–141. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENTEN R. H. Latent phenolase in extracts of broad-bean (Vicia faba L.) leaves. I. Activation by acid and alkali. Biochem J. 1957 Oct;67(2):300–307. doi: 10.1042/bj0670300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty R. E., Racker E. Effect of a coupling factor and its antiserum on photophosphorylation and hydrogen ion transport. Brookhaven Symp Biol. 1966;19:202–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty R. E., Racker E. Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing photophosphorylation. 3. Activation of adenosine triphosphatase and 32P-labeled orthophosphate -adeno-sine triphosphate exchange in chloroplasts. J Biol Chem. 1968 Jan 10;243(1):129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnarrenberger C., Oeser A., Tolbert N. E. Isolation of Plastids from Sunflower Cotyledons during Germination. Plant Physiol. 1972 Jul;50(1):55–59. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert N. E., Oeser A., Kisaki T., Hageman R. H., Yamazaki R. K. Peroxisomes from spinach leaves containing enzymes related to glycolate metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1968 Oct 10;243(19):5179–5184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]