Abstract

This study describes the applications of a naturally occurring small heat shock protein (Hsp) that forms a cage-like structure to act as a drug carrier. Mutant Hsp cages (HspG41C) were expressed in Escherichia coli by substituting glycine 41 located inside the cage with a cysteine residue to allow conjugation with a fluorophore or a drug. The HspG41C cages were taken up by various cancer cell lines, mainly through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The cages were detected in acidic organelles (endosomes/lysosomes) for at least 48 hours, but none were detected in the mitochondria or nuclei. To generate HspG41C cages carrying doxorubicin (DOX), an anticancer agent, the HspG41C cages and DOX were conjugated using acid-labile hydrazone linkers. The release of DOX from HspG41C cages was accelerated at pH 5.0, but was negligible at pH 7.2. The cytotoxic effects of HspG41C–DOX against Suit-2 and HepG2 cells were slightly weaker than those of free DOX, but the effects were almost identical in Huh-7 cells. Considering the relatively low release of DOX from HspG41C–DOX, HspG41C–DOX exhibited comparable activity towards HepG2 and Suit-2 cells and slightly stronger cytotoxicity towards Huh-7 cells than free DOX. Hsp cages offer good biocompatibility, are easy to prepare, and are easy to modify; these properties facilitate their use as nanoplatforms in drug delivery systems and in other biomedical applications.

Keywords: anticancer activity, biomedical application, doxorubicin, drug delivery system, protein nanocapsules, small heat shock protein

Introduction

Many types of drug delivery systems, including liposomes,1 emulsions,2 polymers,3,4 and proteins,5 have been proposed to enhance the therapeutic effects and reduce the side effects of drugs. In particular, macromolecular prodrugs based on polymer–drug6–10 and protein–drug conjugates11,12 have received considerable attention. Unlike liposomes and polymeric micelles from which encapsulated drugs tend to be released in the bloodstream before accumulating at their target site through dissociation of thermodynamically self-assembled structures,13,14 drug–carrier conjugates can be kept in a stable conformation if appropriate linkers are used. Although the conjugates have relatively stable characteristics, the drugs can be released from the conjugates through sensing unique cellular and subcellular environmental factors, including pH,6–11 redox potential,9,15 and enzyme activity,3,12,16 and can then promote cell death. In the context of pH-sensitive prodrug systems, numerous acid-cleavable linkers, including imine,17 acetal,18 oxime,19 and hydrazine,6–11 have been reported. These linkers were generally stable at physiological conditions (pH ~7) but were hydrolyzed in the acidic environments of endosomes (pH 5–6) and lysosomes (pH 4.7).20

As a drug carrier, this study has focused on the naturally occurring small heat shock protein 16.5 (Hsp), which originated from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Hsp forms a cage-like structure with an outer diameter of 12 nm and an inner diameter of 6.5 nm through self-assembly of 24 individual monomeric proteins.21 This Hsp cage has a monodispersed size, a well-defined structure, and can be expressed in Escherichia coli in a highly reproducible manner unlike other polymeric prodrugs that often require multistep reactions. In addition, the Hsp cage has eight pores with a diameter of 3 nm that allow transfer from the external to internal environment of the cage of various molecules, including fluorophores, drugs, and metal ions.21 Therefore, Hsp cages can be fabricated with functional molecules localized on the interior and exterior of Hsp cages. Hsp cages have also been used for biomedical applications due to their advantageous biocompatibility, biodegradability, and easy fabrication through chemical/genetic strategies.22–25 Although Hsp cages have several favorable characteristics making them suitable as drug carriers, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, only a few reports have examined this possibility.11

In this study, an Hsp cage-based prodrug was developed. Doxorubicin (DOX) was used as a model drug because it has been clinically used to treat many cancers for more than four decades.26,27 The interior of the native Hsp cages was first mutated to introduce cysteine residues (HspG41C), which form a complex with molecules such as fluorophores and drugs possessing maleimide groups following modification by simple thiol-maleimide chemistry. Using fluorophore (Alexa Fluor® 488)-labeled HspG41C cages (HspG41C–Alx), cellular uptake, endocytic pathways involved, and subcellular localization of HspG41C–Alx in various cancer cell lines were determined. To assess the potential applicability of Hsp cages as drug carriers, DOX was linked to Hsp cages through an acid-labile hydrazone linker by a single chemical reaction between cysteine residues inside the HspG41C cage and a maleimide group of a DOX derivative, DOX–N-(ɛ-maleimidocaproic acid) hydrazide, trifluoroacetic acid salt (EMCH), yielding HspG41C–DOX. The cytotoxic effects of HspG41C–DOX were then evaluated using three cancer cell lines.

Material and methods

Expression and purification of HspG41C cages

The pET21a(+) vector-encoded HspG41C mutant, in which the glycine residue at position 41 of wild-type Hsp was substituted with a cysteine residue, was prepared by polymerase chain reaction-mediated mutagenesis with appropriate primers. The success of mutagenesis was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The HspG41C mutant protein was obtained from E. coli, and was purified by anion exchange chromatography and size exclusion chromatography. The BL21-Gold (DE3) strain of E. coli (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for HspG41C expression.

E. coli containing the pET21a(+) plasmid vector were grown in 2 × YT medium containing 100 μg/mL of ampicillin at 37°C. When the culture medium’s optical density at 600 nm reached 0.5–0.6, the expression of the recombinant protein was induced by 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) for 4 hours at 37°C. After collecting the cells by centrifugation, the cells were suspended in 25 mM monopotassium phosphate solution (containing 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 2 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.0) and stored at −80°C until purification. The cell suspensions were then sonicated to disrupt the cell membrane. The resulting cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. Proteins were purified using a HiLoad™ 26/10 Q Sepharose™ High Performance anion exchange column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and a size exclusion chromatography column (TSKgel® G3000SW; Tosoh Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The success of purification was confirmed by 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Synthesis of HspG41C–Alx

To generate HspG41C complexes with fluorophores located inside the HspG41C cages, HspG41C (2.5 mg, 152 nmol cysteine residues) was reacted with Alexa Fluor 488 C5-maleimide (0.13 mg, 182 nmol; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 hours at room temperature. The reactant was further incubated for 20 hours at 4°C. Unreacted Alexa Fluor 488 C5-maleimide was removed by ultrafiltration using Amicon® Ultra Centrifugal Filters with a molecular weight cut-off of 100,000 (Merck).

Synthesis of maleimide hydrazone derivatives of DOX (DOX–EMCH)

DOX–EMCH was synthesized as previously reported.9 Briefly, DOX (25 mg, 43 μmol; Wako) and EMCH (44 mg, 129 μmol; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were dissolved in 12 mL methanol, and then two drops of trifluoroacetic acid were added using a Pasteur pipette. The reaction solution was stirred overnight at room temperature in the dark. The reaction solution was then concentrated to 1 mL by evaporation and precipitated to ethyl acetate three times. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation and dried under a vacuum.

Hydrogen-1 (1H) nuclear magnetic resonance (dimethyl sulfoxide-d6, 298 K, 500 MHz), δ (ppm from tetramethylsilane): 10.29 (1H, s, –N-NH-CO–), 7.93 (1H, br, Ar), 7.80 (1H, br, Ar), 7.67 (1H, br, Ar), 6.97 (2H, s, double bond of maleimide group), 4.97 (1H, m, –CH2-CH(–O–)2 of sugar ring), 4.17 (2H, m, –CH– of sugar ring), 4.04 (3H, s, CH3O-Ar), 3.36 (2H, t, –CH2–CH2-N=), 2.63–3.23 (3H, m, –CH2– of aliphatic ring, –CH– of sugar ring), 2.10–2.36 (6H, m, –CH2– of sugar ring and aliphatic ring), 1.29–1.68 (6H, m, –CH2-(CH2)3-CH2–), 1.17 (3H, m, CH3-CH of sugar ring).

Synthesis of DOX–EMCH-modified HspG41C (HspG41C–DOX)

HspG41C (3.2 mg, 0.19 μmol, 0.19 μmol of cysteine residue) was dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (20 mM, pH 7.2) followed by the addition of DOX–EMCH (0.6 mg, 0.78 μmol). After stirring for 2 hours, the solution was incubated for 22 hours at 4°C. Unreacted DOX–EMCH was removed by ultrafiltration as described above, which was repeated until the filtrate turned from red to clear.

Measurement of DOX release from HspG41C–DOX

HspG41C–DOX was dissolved with 0.2 M of phosphate–citrate buffer (pH 5.0) or 0.2 M of phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) to adjust the final concentration of DOX to 52 μM and final volume to 100 μL. After these HspG41C–DOX solutions were incubated at 37°C for 1, 2, or 3 days, released DOX was removed by ultracentrifugation using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters with a molecular weight cut-off of 100,000 (Merck). The final volume of remaining HspG41C–DOX solution was adjusted to 100 μL by each buffer described above and then absorbance of diluted HspG41C–DOX solution was measured using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (V-560; JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). The percentage of released DOX from HspG41C–DOX was calculated using the following equation: percentage of DOX released = ([ADOX, 0 − ADOX, X]/ADOX, 0) × 100, where ADOX, 0 and ADOX, X were the absorbance of DOX at 495 nm at Day 0 and Day X after incubation, respectively.

Cell culture

Huh-7 cells (human hepatoma), HepG2 cells (human hepatoma), HeLa cells (human cervical carcinoma), and Suit-2 cells (human pancreatic cancer) were obtained from Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan), and Hep3B cells (human hepatoma) and U87-MG cells (human glioblastoma) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All cells were cultured in an appropriate medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin-B (all from Life Technologies) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air at 37°C. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium was used for cultivation of Huh-7, HepG2, and U87-MG cells; Eagle’s minimal essential medium containing nonessential amino acids was used for Hep3B and HeLa cells; and Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 was used for Suit-2 cells (all growth media were from Wako).

Fluorescence microscopic observation of HspG41C–Alx uptake

Cells were seeded on 96-well culture plates at an initial cell density of 10,000/well and were cultured for 1 day in 100 μL of the specified medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The final concentration of HspG41C–Alx was adjusted to 40 nM (1 μM of subunit protein) using Opti-MEM® (Life Technologies) and 100 μL of the diluted HspG41C–Alx was added to each well. After incubation for 24 hours, the medium was replaced with fresh Opti-MEM. Hoechst 33342 (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was used to stain the nuclei. Fluorescence images were obtained using a BZ-9000 fluorescence microscope (Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan).

Identification of the pathway for HspG41C–Alx uptake

Suit-2 cells were harvested on poly-L-lysine-coated 48-well plates at an initial density of 50,000 cells/well and were grown overnight. Cells were treated with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing chlorpromazine (28 μM), amiloride (500 μM), and/or filipin III (15 μM) for 1 hour (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Then, 84 nM of HspG41C–Alx solution containing the same concentrations of these inhibitors was added to the cells. Two hours after transfection, the cells were rinsed three times with phosphate buffered saline and lysed in lysis buffer (pH 7.5, 20 mM tris[hydroxymethyl]aminomethane hydrochloride, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.05% Triton X-100). The cells lysates were transferred to black-bottomed 96-well plates and the fluorescence intensity of each sample was measured using a microplate reader (ARVO MX 1420; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Fluorescence microscopic observation of the subcellular localization of HspG41C–Alx cages and distribution of DOX

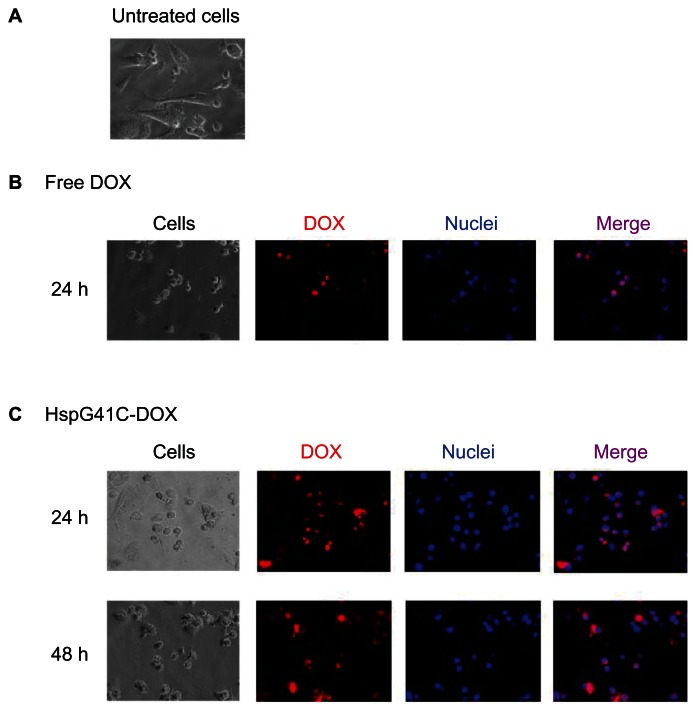

Suit-2 cells were harvested on 48-well plates at an initial density of 10,000 cells/well and were grown overnight. Then, 40 nM of HspG41C–Alx was added to the cells and the cells were cultured for 24 or 48 hours. Acidic organelles and mitochondria were stained using LysoTracker® Red DND-99 and MitoTracker® Red (Life Technologies), respectively. To assess the distribution of DOX, Suit-2 cells were harvested on 48-well plates at an initial density of 50,000 cells/well and were grown overnight. HspG41C–DOX containing 20 μM of DOX or the same concentration of free DOX was added to the cells, which were incubated for 24 or 48 hours. Fluorescence images were obtained using the BZ-9000 fluorescence microscope.

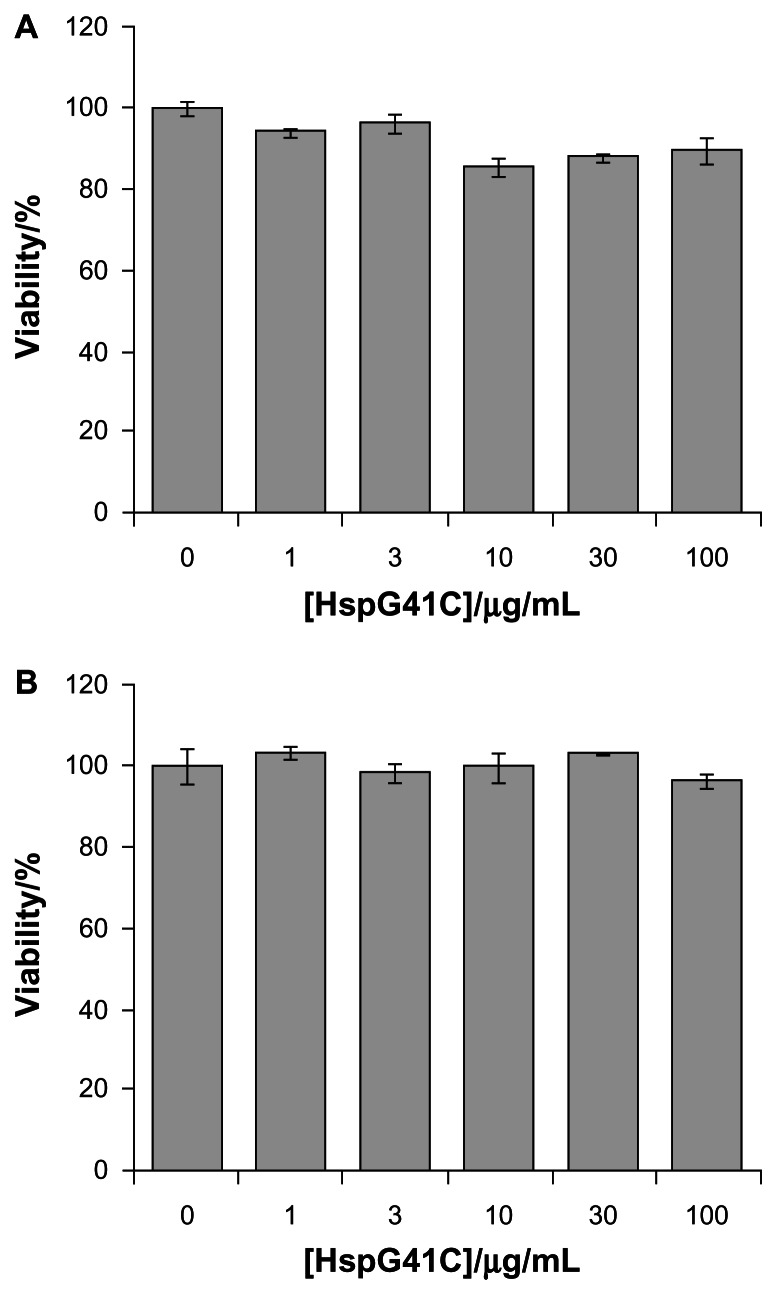

Evaluation of HspG41C cytotoxicity

Cells were harvested on white-bottomed 96-well plates at an initial cell density of 10,000 cells/well and were grown overnight. Then, 100 μL of HspG41C dissolved in Opti-MEM (1–100 μg/mL) was added to the cells, which were then incubated for 24 hours. Cell viability was measured using a CellTiter-Glo® luminescent cell viability assay kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Luminescence intensity was measured using the ARVO MX 1420 microplate reader.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity of HspG41C–DOX to cells

The cells were harvested on white-bottomed 96-well plates at an initial cell density of 10,000 cells/well and were grown overnight. Then, 100 μL of HspG41C–DOX dissolved in Opti-MEM (containing 0.3–30 μM of DOX) was added to the cells. After incubation for 24, 48, or 72 hours, cell viability was measured as described above. Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) factors were calculated using Prism® sigmoidal dose response software (GraphPad Prism 6; GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results and discussion

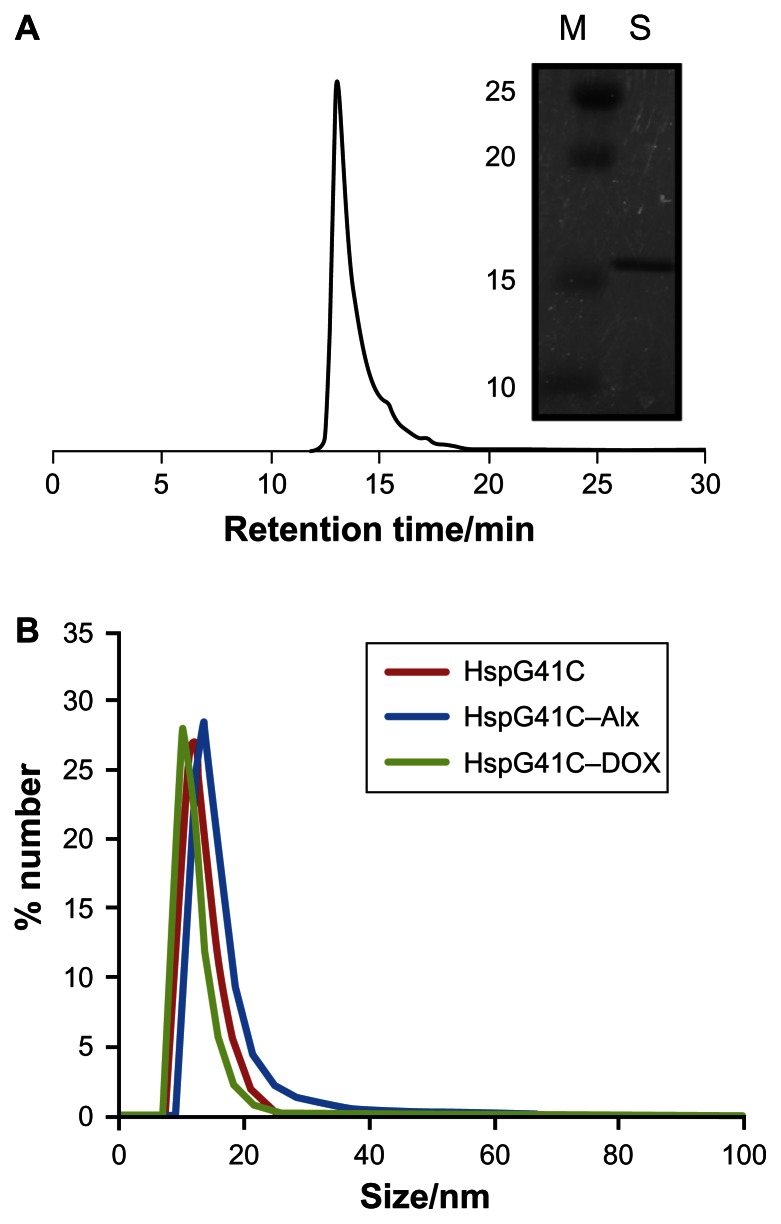

Characterization of HspG41C

Hsp is a naturally occurring protein that forms a cage structure with an external diameter of 12 nm and an internal diameter of 6.5 nm through self-assembly of 24 individual monomeric proteins.21 To introduce the conjugation sites of chemical agents such as fluorophores and drugs, a mutant Hsp cage (HspG41C) was developed by genetically substituting glycine 41, within the interior of the Hsp cage, with cysteine. HspG41C cages were obtained from E. coli, and were purified by anion exchange chromatography and size exclusion chromatography. The resulting size exclusion chromatography profile and sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis revealed that HspG41C was successfully obtained (Figure 1A). Dynamic light scattering measurements confirmed that the resulting HspG41C had a diameter of ~12 nm, which is consistent with previous results (Figure 1B).21 In addition, HspG41C at concentrations of 1–100 μg/mL showed no cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells or Suit-2 cells (Figure 2), indicating that HspG41C is a biocompatible protein with favorable characteristics and is useful as a drug delivery system and in other biomedical applications.

Figure 1.

(A) Size exclusion chromatography profile of HspG41C. The picture to the right shows a typical sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis blot of HspG41C purified by ion exchange chromatography and size exclusion chromatography. (B) Size distribution of HspG41C, HspG41C–Alx, and HspG41C–DOX in phosphate buffered saline.

Abbreviations: HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–Alx, fluorophore (Alexa Fluor® 488)-labeled HspG41C cage; HspG41C–DOX, HspG41C–cage carrying doxorubicin; M, marker; S, monomeric HspG41C.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity assay of HspG41C against (A) Suit-2 cells (human pancreatic cancer cells) and (B) HepG2 cells (human hepatocellular carcinoma cells).

Note: Data represents mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Abbreviation: HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage.

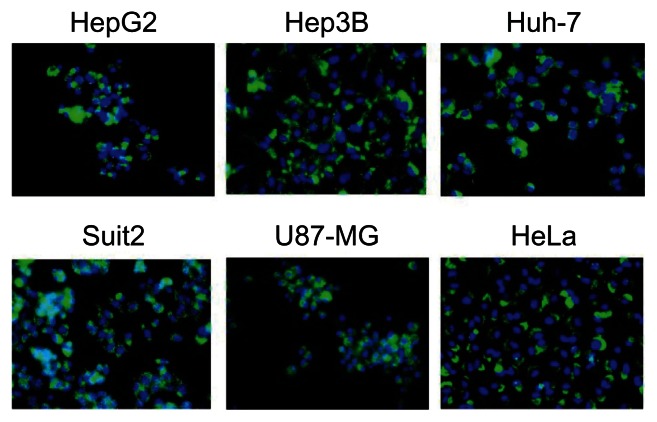

Cellular uptake of HspG41C by various cell lines

To examine whether the HspG41C cages could be taken up by the cells, HspG41C–Alx were prepared by Michael addition reaction between Alexa Fluor 488 maleimide and the unique cysteine residue of HspG41C. The resulting HspG41C–Alx had a comparable size distribution to that of unmodified HspG41C (Figure 1B). HspG41C–Alx was added to cultures of HepG2, Hep3B, Huh-7, Suit-2, U87-MG, and HeLa cells. HspG41C–Alx uptake was observed by fluorescence microscopy 24 hours later. Green fluorescence corresponding to HspG41C–Alx was detected in each of the cell lines (Figure 3), confirming that HspG41C-Alx could be taken up by various cell types.

Figure 3.

Uptake of HspG41C–Alx cages by cancer cell lines.

Notes: Cells were incubated with 40 nM of HspG41C (1 μM of protein monomer unit) for 24 hours and observed by fluorescence microscopy. Green indicates HspG41C–Alx cages; blue indicates the nuclei.

Abbreviations: HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–Alx, fluorophore (Alexa Fluor® 488)-labeled HspG41C cage.

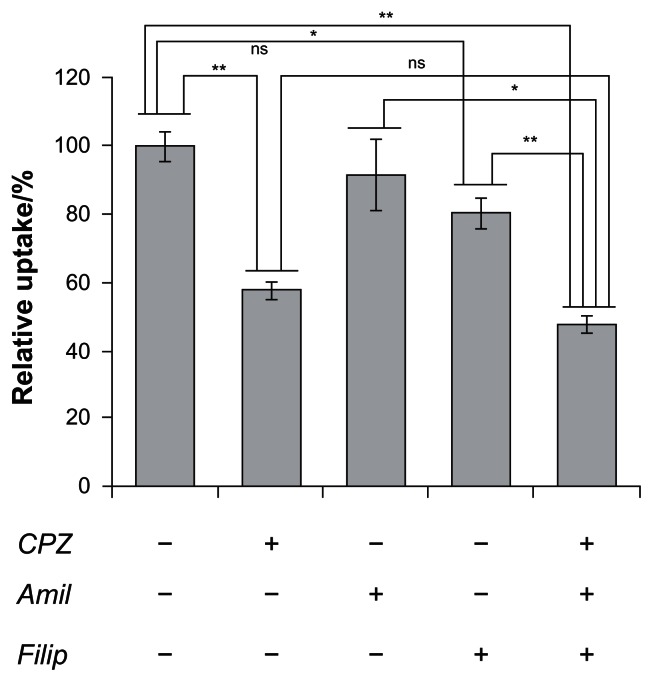

Endocytic mechanism and subcellular localization of HspG41C cages

The HspG41C nanoparticles were mostly internalized by endocytosis. The endocytic pathways are broadly classified into four groups, namely clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae-mediated endocytosis, macropinocytosis, and clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocyotosis.28 Therefore, to determine the endocytic pathway involved in HspG41C internalization, the following compounds that inhibit specific endocytic pathways were used (Figure 4): chlorpromazine, which inhibits clathrin-mediated endocytosis;29 amiloride, which inhibits macropinocytosis;30 and filipin III, which inhibits caveolae-mediated endocytosis.31 Pretreatment of Suit-2 cells with amiloride and filipin III decreased the cellular uptake of HspG41C by 8% and 19%, respectively, compared with untreated cells. On the other hand, pretreatment with chlorpromazine elicited a much greater decrease (42%) in the uptake of HspG41C. Pretreatment with all three compounds simultaneously elicited a similar decrease (52%) in the uptake of HspG41C to that of chlorpromazine alone. These results indicate that main uptake pathway of HspG41C was clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of cellular uptake of HspG41C–Alx cages by three types of endocytosis inhibitors.

Notes: Uptake of HspG41C–Alx cages was measured as the fluorescence intensity after incubation with HspG41C–Alx cages for 2 hours. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; data represents mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Abbreviations: Amil, amiloride; CPZ, chlorpromazine; Filip, filipin III; HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–Alx, fluorophore (Alexa Fluor® 488)-labeled HspG41C cage; ns, not significant.

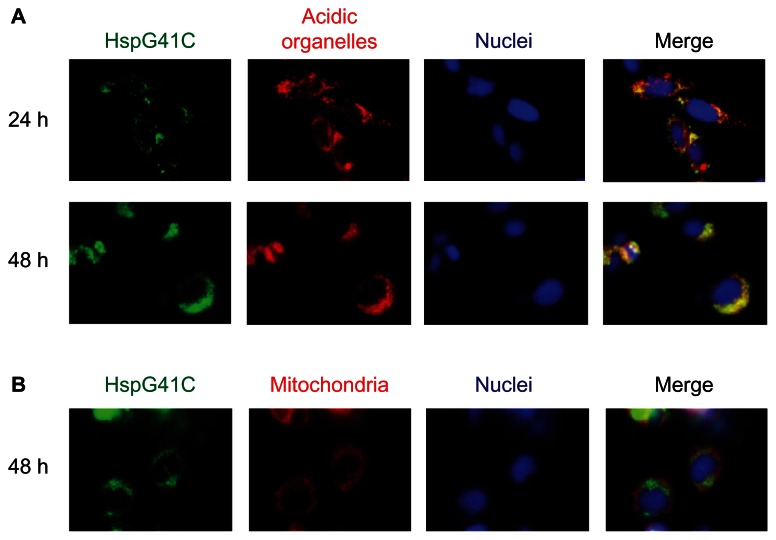

Nanoparticles that are taken up by clathrin-mediated endocytosis usually enter endosomal vesicles and are then translocated to lysosomes with more acid pH (5.0–6.5) compared with the cytosol (pH 7.2).20,28 Some nanoparticles escape these acidic organelles and accumulate in the mitochondria and nuclei. Therefore, to determine the subcellular localization of HspG41C, Suit-2 cells were incubated with HspG41C–Alx for 24 or 48 hours and the colocalization of HspG41C–Alx with specific organelles (acidic organelles, mitochondria, and nuclei) was observed by fluorescence microscopy. The fluorescence images showed that HspG41C–Alx was mainly localized in the endosomes and/or lysosomes at 24 hours based on the merged fluorescence of HspG41C–Alx and LysoTracker (shown in yellow; Figure 5A). After 48 hours, most of the HspG41C–Alx remained in the endosomes/lysosomes. Very slight colocalization of HspG41C–Alx in mitochondria (stained with MitoTracker Red) was found at 48 hours because accumulation of HspG41C–Alx in mitochondria required endosomal escape (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence microscopic observation of the subcellular localization of HspG41C cages. Suit-2 cells were incubated with 40 nM of HspG41C–Alx for 24 or 48 hours and observed by fluorescence microscopy. (A) Acidic organelles (endosomes/lysosomes) and (B) mitochondria were stained with LysoTracker® Red and MitoTracker® Red, respectively (both are shown in red). Nuclei (blue) were stained by Hoechst 33342.

Abbreviations: HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–Alx, fluorophore (Alexa Fluor® 488)-labeled HspG41C cage.

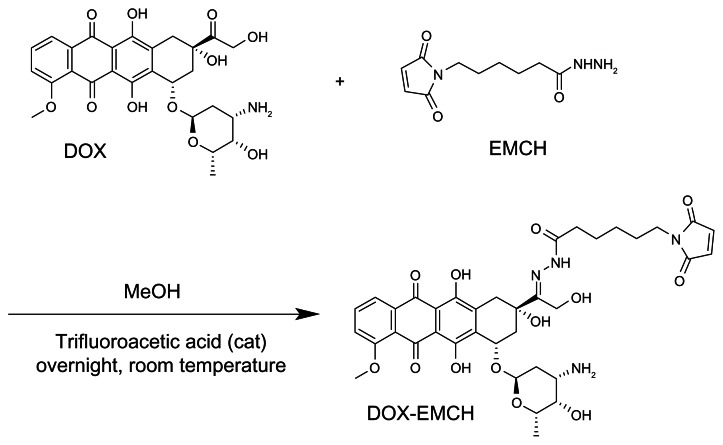

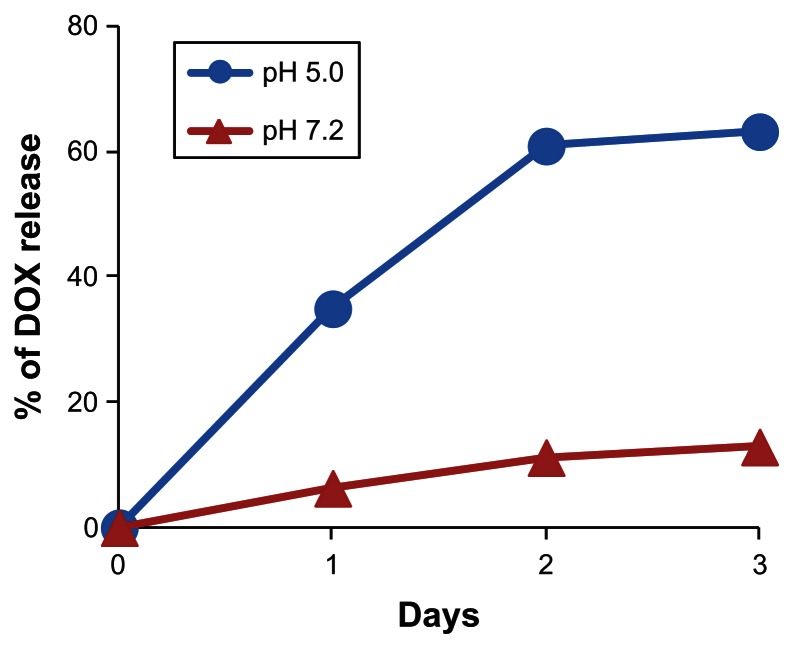

Synthesis of HspG41C–DOX and DOX release

Next, HspG41C–DOX was prepared as a drug delivery system by covalently binding a DOX derivative (DOX–EMCH; Figure 6) by acid-labile hydrazone binding in the interior of HspG41C cages. This was achieved by simple Michael addition reactions between a maleimide group of DOX–EMCH and the unique cysteine residue of HspG41C. After conjugation, 20 molecules of DOX–EMCH were covalently bound to one HspG41C–DOX cage based on the absorbance of DOX–EMCH (ɛ495 = 8030 M−1 cm−1). No obvious change in size distribution of HspG41C–DOX was detected when compared with unmodified HspG41C (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 7, approximately 60% of conjugated DOX was released from HspG41C–DOX 2 days after incubating at pH 5.0 and the amount of DOX released was almost comparable between samples incubated for 2 days and 3 days. By contrast, a much smaller amount of DOX (~10%) was released after incubating at pH 7.2 for 3 days. These results indicate that the release of DOX from HspG41C is accelerated in acidic environments, as in endosomes/lysosomes.

Figure 6.

Synthetic scheme of DOX–EMCH.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; EMCH, N-(ɛ-maleimidocaproic acid) hydrazide, trifluoroacetic acid salt; MeOH, methanol.

Figure 7.

Time course of DOX release from HspG41C–DOX at pH of 5.0 and 7.2.

Note: Data represents mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–DOX, HspG41C cage carrying doxorubicin.

Evaluation of HspG41C–DOX cytotoxicity

Cytotoxic assays of HspG41C-DOX against Suit-2, HepG2, and Huh-7 cancer cell lines were then performed. HspG41C–DOX and free DOX at concentrations of 0.3–30 μM were added to the cells and the number of viable cells was measured using a CellTiter-Glo kit at the specified times (24–72 hours) (Figure S1). The IC50 values of HspG41C–DOX and free DOX were then determined (Table 1). The morphology of Suit-2 cells changed from a “sharp” appearance (Figure 8A) to a “round” appearance at 24 hours after treatment with free DOX (Figure 8B) and HspG41C–DOX (Figure 8C), predominantly as a result of cell death. The IC50 values of HspG41C–DOX in Suit-2 and HepG2 cells were three to four times higher than those of free DOX. In Huh-7 cells, the IC50 values of both DOX formations were almost identical.

Table 1.

Half maximal inhibitory concentration values of a mutant heat shock protein cage (HspG41C) carrying doxorubicin and free doxorubicin

| Cells | Exposure time (hours) | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HspG41C–DOX | Free DOX | ||

| Huh-7 (hepatoma) | 24 | 16 | >30 |

| 48 | 5.5 | 10 | |

| 72 | 1.1 | 1.9 | |

| HepG2 (hepatoma) | 24 | 20 | 4.5 |

| 48 | 7.8 | 1.2 | |

| 72 | 4.8 | 1.2 | |

| Suit-2 (pancreatic cancer) | 24 | >30 | >30 |

| 48 | 4.5 | 1.6 | |

| 72 | 2.7 | 1.4 | |

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; HspG41C–DOX, mutant heat shock protein cage (HspG41C) carrying doxorubicin; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration.

Figure 8.

Fluorescence microscopic analysis of the subcellular localization of DOX in Suit-2 cells. (A) Untreated Suit-2 cells. Cellular distribution of (B) free DOX and (C) HspG41C–DOX.

Notes: Red indicates DOX; blue indicates the nuclei.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–DOX, HspG41C cage carrying doxorubicin.

It was hypothesized that the weaker cytotoxicity of HspG41C–DOX compared with free DOX was caused by differences in subcellular localization between both formations of DOX because DOX can induce cell death in various ways including inhibition of DNA topoisomerase II, DNA binding, DNA intercalation, and inhibition of DNA replication26,27 as well as mitochondrial malfunction through nonspecific oxidative damage towards mitochondrial inner and outer membranes and interactions with mitochondrial enzymes and DNA.26 As shown in Figure 8B and C, both formations of DOX were predominantly found in the cytoplasm and nuclei. It was then further investigated whether released DOX reached the mitochondria using MitoTracker Green, a commercially available staining reagent for mitochondria. Unfortunately, after treatment with HspG41C–DOX and DOX, mitochondria were difficult to stain maybe due to the death of cells (data not shown). Therefore, it was difficult to clarify the reason why HspG41C–DOX showed lower cytotoxicity than free DOX based on the differences in subcellular localization. Another possible reason for weaker cytotoxicity of HspG41C–DOX is considered to be the relatively low amount of DOX released from HspG41C–DOX. As shown in Figure 7, ~60% of DOX was released from HspG41C–DOX at 3 days after incubation in buffered solution with pH 5.0 (simulating pH of the late endosome), while only ~10% of DOX was released when incubated in buffered solution with pH 7.2 (simulating pH of the cytoplasm). These results showed that most of DOX can be released from HspG41C–DOX in acidic organelles but not in cytoplasm, and DOX cannot be completely released at 3 days after incubation at pH 5.0. Therefore, to increase the cytotoxicity of HspG41C–DOX, the hydrazone linkers should be replaced with more effective acid-cleavable linkers to increase the amount of DOX released from HspG41C–DOX. In a previous report, poly(L-lactic acid)-poly(ethylene glycol) diblock copolymers linked with DOX using a cis-aconityl linker enabled quicker release of DOX at pH 5 compared with the use of a hydrazone linker, whereas the cis-acotinyl bond was almost completely stable at pH 7.10 Therefore, substitution of a hydrazone linker with a cis-acotinyl linker may be a promising approach to enhance the cytotoxicity effect of the HspG41C–DOX cage used in this study.

Many types of DOX conjugates connecting through hydrazone linkers (eg, polymer, polyamino acid, and protein conjugates) were reported and these typically showed dozens of times lower cytotoxicity than that of free DOX in vitro.32,33 Therefore, the HspG41C–DOX conjugate was a slightly superior system in vitro compared with others. Interestingly, in contrast to in vitro experiments, DOX conjugates exhibited greater inhibition of tumor growth without severe side effects in healthy tissue when applied to tumor-xenografted animal models.32,33 Therefore, to fully assess the therapeutic effect and side effects, additional in vivo experiments using HspG41C–DOX are required.

Future plans

As described above, a major drawback of the present HspG41C–DOX was lower cytotoxicity than free DOX possibly due to slow release of DOX from HspG41C–DOX. Therefore, an attempt to overcome this problem through exchanging the hydrazone linkers to more effective acid cleavable linkers (eg, cis-aconityl linkers) will be made. Also, for in vivo application, specific drug delivery to target cells was very important in order to avoid any undesirable side effects. An advantage of Hsp cages is that the peptide ligand can be modified by the chemical/genetic method,22,23 enabling the delivery of cytotoxic reagents to specific cells. It was previously reported that Hsp cages could specifically target human hepatoma cells after binding human hepatoma binding peptides (SP94 peptides) to the surface of the Hsp cages using poly(ethylene glycol) linkers. The resulting HspSP94 cage was specifically taken up by human hepatoma cells but not by normal liver cells.22 Accordingly, an attempt will be made to modify the peptide to Hsp cages and changing the linker between Hsp and DOX to a more acid-responsive linker, which will enhance the usefulness of Hsp cages in a drug delivery system.

Conclusion

It has been shown that genetically engineered HspG41C cages provide a useful drug delivery system of DOX to various cancer cell lines. The HspG41C cages were taken up by various cell lines, mainly through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, without cytotoxic effects, and were localized in acidic organelles for at least 48 hours. Cysteine residues inside the HspG41C cages can be chemically modified to bind to various drugs and fluorophores. As a model drug delivery system, HspG41C–DOX cages were taken up by cells and DOX was released from HspG41C–DOX following cleavage of the hydrazone bonds between HspG41C and DOX in acidic organelles, leading to cell death. Taking into account the low release rate of DOX from HspG41C, HspG41C–DOX exhibited comparable activity towards HepG2 and Suit-2 cells and slightly stronger cytotoxicity towards Huh-7 cells than free DOX. Hsp cages offer good biocompatibility, are easy to prepare, and are easy to modify; these properties facilitate their use as nanoplatforms for drug delivery systems and in other biomedical applications. Further refinements of HspG41C–DOX are still required, including changing the linker between DOX and the Hsp cages, and improving cell specificity.

Supplementary figure

Cytotoxicity of (A, C and E) HspG41C–DOX and (B, D and F) free DOX.

Notes: One to three days after adding HspG41C–DOX and free DOX (concentrations of DOX were 0.3–30 μM) to (A and B) Huh-7 cells, (C and D) HepG2 cells, (E and F) and Suit-2 cells, cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo® kit. Data represents mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–DOX, HspG41C cage carrying doxorubicin.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by a Health Labor Sciences Research Grant (Research on Publicly Essential Drugs and Medical Devices) from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan, and the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology of Japan (SCF funding program “Innovation Center for Medical Redox Navigation”), and a Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (number 23800045) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ceh B, Wintherhalter M, Frederik PM, Vallner JJ, Lasic DD. Stealth® liposomes: from theory to product. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;24(2–3):165–177. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tahara Y, Kaneko T, Toita R, et al. A novel double-coating carrier produced by solid-in-oil and solid-in-water nanodispersion technology for delivery of genes and proteins in cells. J Control Release. 2012;161(3):713–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toita R, Kang JH, Tomiyama T, et al. Gene carrier showing all-or-none response to cancer cell signaling. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(37):15410–15417. doi: 10.1021/ja305437n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cover NF, Lai-Yuen S, Parsons AK, Kumar A. Synergetic effects of doxycycline-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for improving drug delivery and efficacy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:2411–2419. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S27328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsadek B, Kratz F. Impact of albumin on drug delivery – new applications on the horizon. J Control Release. 2012;157(1):4–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du JZ, Du XJ, Mao CQ, Wang J. Tailor-made dual pH-sensitive polymer–doxorubicin nanoparticles for efficient anticancer drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(44):17560–17563. doi: 10.1021/ja207150n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L, Cheng R, Tao H, et al. Endosomal pH-activatable poly(ethylene oxide)-graft-doxorubicin prodrugs: synthesis, drug release, and biodistribution in tumor-bearing mice. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(5):1460–1467. doi: 10.1021/bm101340u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae Y, Fukushima S, Harada A, Kataoka K. Design of environment-sensitive supramolecular assemblies for intracellular drug delivery: polymeric micelles that are responsive to intracellular pH change. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42(38):4640–4643. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia Z, Wong L, Davis TP, Bulmus V. One-pot conversion of RAFT-generated multifunctional block copolymers of HPMA to doxorubicin conjugated acid- and reductant-sensitive crosslinked micelles. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(11):3106–3113. doi: 10.1021/bm800657e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo HS, Lee EA, Park TG. Doxorubicin-conjugated biodegradable polymeric micelles having acid-cleavable linkages. J Control Release. 2002;82(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flenniken ML, Liepold LO, Crowley BE, Willits DA, Young MJ, Douglas T. Selective attachment and release of a chemotherapeutic agent from the interior of a protein cage architecture. Chem Commun (Camb) 2005;(4):447–449. doi: 10.1039/b413435d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansour AM, Drevs J, Esser N, et al. A new approach for the treatment of malignant melanoma: enhanced antitumor efficacy of an albumin-binding doxorubicin prodrug that is cleaved by matrix metalloproteinase 2. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):4062–4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H, Kim S, He W, et al. Fast release of lipophilic agents from circulating PEG-PDLLA micelles revealed by in vivo Forster resonance energy transfer imaging. Langmuir. 2008;24(10):5213–5217. doi: 10.1021/la703570m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiwpanich S, Ryu JH, Bickerton S, Thayumanavan S. Noncovalent encapsulation stabilities in supramolecular nanoassemblies. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(31):10683–10685. doi: 10.1021/ja105059g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santra S, Kaittanis C, Santiesteban OJ, Perez JM. Cell-specific, activatable, and theranostic prodrug for dual-targeted cancer imaging and therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(41):16680–16688. doi: 10.1021/ja207463b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denmeade SR, Nagy A, Gao J, Lilja H, Schally AV, Isaacs JT. Enzymatic activation of a doxorubicin-peptide prodrug by prostate-specific antigen. Cancer Res. 1998;58(12):2537–2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillies ER, Frechet JM. pH-responsive copolymer assemblies for controlled release of doxorubicin. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(2):361–368. doi: 10.1021/bc049851c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillies ER, Frechet JM. A new approach towards acid sensitive copolymer micelles for drug delivery. Chem Commun (Camb) 2003;14:1640–1641. doi: 10.1039/b304251k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin Y, Song L, Su Y, et al. Oxime linkage: a robust tool for the design of pH-sensitive polymeric drug carriers. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(10):3460–3468. doi: 10.1021/bm200956u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(1):50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KK, Kim R, Kim SH. Crystal structure of a small heat-shock protein. Nature. 1998;394(6693):595–599. doi: 10.1038/29106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toita R, Murata M, Tabata S, et al. Development of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell-targeted protein cages. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23(7):1494–1501. doi: 10.1021/bc300015f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murata M, Narahara S, Umezaki K, et al. Liver cell specific targeting by the preS1 domain of hepatitis B virus surface antigen displayed on protein nanocages. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:4353–4362. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S31365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sao K, Murata M, Umezaki K, et al. Molecular design of protein-based nanocapsules for stimulus-responsive characteristics. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sao K, Murata M, Fujisaki Y, et al. A novel protease activity assay using a protease-responsive chaperone protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383(3):293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung K, Reszka R. Mitochondria as subcellular targets for clinically useful anthracyclines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;49(1–2):87–105. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kizek R, Adam V, Hrabeta J, et al. Anthracyclines and ellipticines as DNA-damaging anticancer drugs: recent advances. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133(1):26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahay G, Alakhova DY, Kabanov AV. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J Control Release. 2010;145(3):182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang LH, Rothberg KG, Anderson RG. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J Cell Biol. 1993;123(5):1107–1117. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hewlett LJ, Prescott AR, Watts C. The coated pit and macropinocytic pathways serve distinct endosome populations. J Cell Biol. 1994;124(5):689–703. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamaze C, Schmid SL. The emergence of clathrin-independent pinocytic pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7(4):573–580. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae Y, Nishiyama N, Fukushima S, Koyama H, Matsumura Y, Kataoka K. Preparation and biological characterization of polymeric micelle drug carriers with intracellular pH-triggered drug release property: tumor permeability, controlled subcellular drug distribution, and enhanced in vivo antitumor efficacy. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(1):122–130. doi: 10.1021/bc0498166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kratz F, Warnecke A, Scheuermann K, et al. Probing the cystein-34 position of endogenous serum albumin with thiol-binding doxorubicin derivatives. Improved efficacy of an acid-sensitive doxorubicin derivative with specific albumin-binding properties compared to that of the parent compound. J Med Chem. 2002;45(25):5523–5533. doi: 10.1021/jm020276c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cytotoxicity of (A, C and E) HspG41C–DOX and (B, D and F) free DOX.

Notes: One to three days after adding HspG41C–DOX and free DOX (concentrations of DOX were 0.3–30 μM) to (A and B) Huh-7 cells, (C and D) HepG2 cells, (E and F) and Suit-2 cells, cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo® kit. Data represents mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; HspG41C, mutant heat shock protein cage; HspG41C–DOX, HspG41C cage carrying doxorubicin.