Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To identify generalizable ways that comorbidity affects older adults’ experiences in a health service program directed toward an index condition and to develop a framework to assist clinicians in approaching comorbidity in the design, delivery, and evaluation of such interventions.

DESIGN

A qualitative data content analysis of interview transcripts to identify themes related to comorbidity.

SETTING

An outpatient low-vision rehabilitation program for macular disease.

PARTICIPANTS

In 2007/08, 98 individuals undergoing low-vision rehabilitation and their companions provided 624 semistructured interviews that elicited perceptions about barriers and facilitators of successful program participation.

RESULTS

The interviews revealed five broad themes about comorbidity: (i) “good days, bad days,” reflecting participants’ fluctuating health status during the program because of concurrent medical problems; (ii) “communication barriers.” which were sometimes due to participant impairments and sometimes situational; (iii) “overwhelmed,” which encompassed pragmatic and emotional concerns of participants and caregivers; (iv) “delays,” which referred to the tendency of comorbidities to delay progress in the program and to confer added inconvenience during lengthy appointments; and (v) value of companion involvement in overcoming some barriers imposed by comorbid conditions.

CONCLUSION

This study provides a taxonomy and conceptual framework for understanding consequences of comorbidity in the experience of individuals receiving a health service. If confirmed in individuals receiving interventions for other index diseases, the framework suggests actionable items to improve care and facilitate research involving older adults.

Keywords: health services research, clinical medicine, aging, patient-centered, multicomponent intervention

In patient care, clinicians typically use therapies intended to treat a single disease, but approximately two-thirds of older Americans have two or more chronic conditions,1 and 23% have five or more.2 People with more than one chronic disease are frequent users of the healthcare system, accounting for 96% of Medicare expenditures.1 Although medical complexity is becoming the norm rather than the exception in an aging society, many prevailing treatment paradigms do not account for comorbidity.3–5 Although clinicians may recognize the need to adjust care plans for some concurrent conditions, the National Institute of Aging Taskforce on Comorbidity concluded that one impediment to improving overall practice is the considerable knowledge gap about how comorbidity affects the efficacy and tolerance of many treatments.6 Despite an increasing emphasis on patient-centered care,7 there exists no in-depth description and analysis of patient and caregiver perspectives about the consequences of comorbidity within a multicomponent health service directed toward a particular disease.

Older adults frequently receive treatment through multicomponent interventions, which usually involve assessment and expertise from more than one provider, as well as education-based components.8,9 Multicomponent interventions have been shown to improve outcomes in people with many index conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, arthritis, congestive heart failure, cardiac disease, macular disease, and cancer.10–15 Progressive models of primary care, such as the Patient-Centered Medical Home or Guided Care, coordinate multidisciplinary services to educate and support people in self-management of particular chronic conditions.16–18 Because this type of intervention requires a level of participation and engagement from the individual that goes beyond taking a pill or receiving a device, many opportunities may arise for coexisting conditions to interfere with adherence and treatment success.

Nevertheless, these health services also have the capacity to be adaptive and individualized and thus may be well suited to accommodate the heterogeneous problem of comorbidity.19 Efforts to deliver interventions that serve the broadest spectrum of individuals depend, in part, on anticipating the nature of interference from any number of concurrent health problems. Unfortunately, practitioners lack a set of guiding principles to help them categorize common ways that comorbidity affects people’s experiences in multicomponent interventions.

With the goal of increasing understanding of how comorbidity influences perceived treatment success and patient experience in a multicomponent health service program, transcripts from in-depth interviews that had been conducted with 98 individuals with macular disease undergoing low-vision rehabilitation and their companions were analyzed. The participant sample is illustrative of an aging population, and low-vision rehabilitation represents a targeted health service that addresses a specific problem yet is often delivered to people who have an array of additional health conditions. The objective was to develop a generalizable framework to assist researchers in addressing comorbidity in the development and implementation of multicomponent interventions and to offer clinicians practical steps to help their medically complicated patients navigate these complex health services.

METHODS

Design, Participants, Setting

The data were obtained during a prospective, observational, mixed-methods study to understand barriers to and facilitators of treatment success in older adults receiving low-vision rehabilitation for macular disease. Eligible individuals were those aged 65 and older with macular disease and treated in the Duke Eye Center outpatient low-vision rehabilitation program between September 2007 and March 2008. Low-vision rehabilitation is a specialized health service that incorporates optometry, occupational therapy, and device training, with a goal of preserving functional ability for people with irreversible vision loss.20 For each enrolled participant, the study sought to enroll one companion—a friend or relative with whom the participant had at least weekly contact. The only exclusion criterion was language barrier that prohibited participation in interviews.

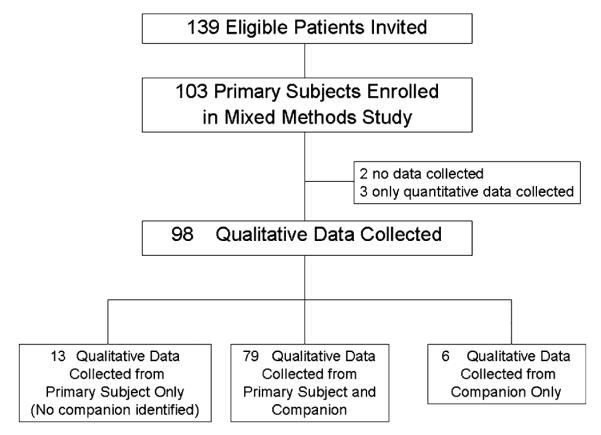

In addition to quantitative data from primary participants,21 interviews were conducted with primary participants and companions. The content analysis presented here made use of the extensive qualitative data available at the conclusion of these interviews. Although purposive sampling would have been favored for purely qualitative research,22 this mixed-methods study aimed to establish a cohort that was comprehensive and representative of the referral population. During each week of the enrollment period, all eligible individuals were invited to participate until the weekly recruitment goal was met. Of 139 individuals approached, 103 (74.1%) gave consent. Those who declined did not differ significantly from study participants according to sex, race, or age. Of 103 enrolled participants, 85 named a companion who participated; qualitative data from the participant and companion were collected on 98 participants (Figure 1). The Duke University Medical Center institutional review board approved the study, and participants provided informed consent.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Data Collection

Two experienced interviewers conducted semistructured, audiotaped interviews with primary participants and companions; companions and participants were always interviewed separately from one another, in private rooms or over the telephone. Open-ended questions about factors that were “helpful” or “key to success,” as well as “challenges” and “disappointments” while receiving the health service guided the interviews (Appendix A). Interviewers used probing techniques to elucidate details and clarify meaning. Respondents were encouraged to provide illustrative examples and vignettes when possible. As is standard in qualitative methodology, data collection and analysis occurred concurrently in an iterative process.23 Guided by investigators’ periodic reflection and discussion, interviewers began to probe about emergent themes, including comorbidity.

To capture evolution of thought and include two different perspectives about the participant’s experience in the longitudinal program, interviewers attempted to contact each primary participant and each companion at four time points separated by at least 30 days, yielding a maximum of eight interviews per participant (four interviews with primary participant and four with companion). In all, 333 participant interviews and 291 companion interviews were available. For 86 of the 98 participants, an interview was available with the participant, the companion, or both at all four time points. Interviewers explored viewpoints as exhaustively as possible while avoiding interview fatigue; interviews varied in length from 5 minutes to 1 hour. Two independent professional transcriptionists transcribed all audiotapes verbatim.

Analysis

ATLAS.ti software version 5.2 (Scientific Software, Berlin, Germany) was used for qualitative data management. Each primary document consisted of interview transcripts from a primary participant and his or her companion, compiled in chronological order. A coding scheme was developed using an iterative process. Two coders representing different disciplines (HEW, NA) applied a limited set of codes to the first three primary documents. The coders compared their results to sharpen or redefine the meaning of each code and to identify themes that required additional codes. As insights emerged related to participant experience in the intervention, new codes were added. A third investigator (KS) periodically reviewed the evolving coding scheme to assess breadth and logic. By reviewing and recoding three to five cases at a time, the coders achieved acceptable consistency and developed a final coding scheme with 71 specific codes.

Using the final coding scheme, the two coders completed the remaining transcripts independently. Double coding was used to increase comprehensiveness of code application; the use of theme review and decision rules also produced highly consistent coding. At completion, the two coders agreed that theoretical saturation was achieved in the interviews.24 One coder (NA) merged and cleaned the coded files using ATLAS.ti software.

The code “comorbidity” was applied to 273 quotations in the transcripts. One investigator (HEW) abstracted these quotations and compiled a description of the types and consequences of specific comorbid conditions mentioned. The 273 quotations were then reviewed for concurrent coding patterns and unique and recurrent sentiments related to comorbidity. Supporting quotations were identified to exemplify emergent themes, and decision rules produced consistent guidelines for underlying attributes that pertained to the themes in conceptually distinct ways. Members of the research team (HEW, HJC, KS) reviewed and discussed the themes and supporting quotations until consensus was reached regarding a taxonomy for the effect of comorbidity on participant experience.

Quantitative Data

The primary participants’ demographic data were determined according to self-report at baseline. Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale,25 and cognitive status was assessed using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, modified version (TICS-m).26,27 Fourteen comorbid conditions were assessed according to self-report of physician diagnosis: coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, arthritis, pulmonary disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, liver disease, kidney disease, cancer, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, hip fracture, and ulcer. Descriptive statistics were determined using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 1 describes characteristics of the 98 primary participants. The mean age was 80.4, and approximately two-thirds were women. Ninety-four participants were white, with age-related macular degeneration being the most common index disease. Depression and cognitive impairment were detected in 27.6% and 19.4%, respectively. Most participants reported at least two of the 14 diagnoses assessed in the baseline interview.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Primary Participants (N = 98)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 80.4 (7.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 66 (67) |

| White, n (%) | 94 (96) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 35 (36) |

| Any college | 45 (46) |

| Beyond college | 18 (18) |

| Married, n (%) | 42 (43) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale score≥5, n (%)25 | 27 (28) |

| Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, modified score≤27, n (%)27 |

19 (19) |

| Number of 14 comorbid diagnoses reported, mean ± SD | 2.7 (1.6) |

| Primary type of macular disease, n (%) | |

| Wet AMD | 54 (55) |

| Dry AMD | 23 (24) |

| Diabetic macular edema | 1 (1) |

| Epiretinal membrane | 2 (2) |

| Other | 18 (18) |

SD = standard deviation; AMD = age-related macular degeneration.

The code “comorbidity” was applied to at least one quotation in 72 of 98 (73.5%) cases. The most frequently mentioned comorbid conditions were hearing impairment (mentioned in 21 cases) and cognitive impairment (mentioned in 25 cases). Other conditions discussed in the interviews included depression or anxiety, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary conditions, falls or balance impairment, and arthritis. Companions were more likely to comment on cognitive impairment, depression, and balance problems or falls, whereas participants more often mentioned pain and arthritis.

A Taxonomy for the Effect of Comorbidity

Participants’ comments were organized into five recurrent themes related to comorbidity. Each theme has underlying attributes that further describe its meaning (Table 2).

Table 2.

Taxonomy of Themes Related to Comorbidity

| Themes | Underlying Attributes | Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Good days, bad days |

Physical health | Fluctuations in severity of chronic conditions, acute health events (falls, infections), waxing and waning symptoms |

| Mental readiness | Inconsistent level of diligence and energy for intervention, shifting priorities | |

| Communication barriers |

Impairment-specific | Hearing impairments, cognitive deficits, visual impairment |

| Non-conducive situations | Fast-paced encounter, distracting setting, generational gap | |

| Overwhelmed | Pragmatic concerns | Keeping appointments, competing health objectives, coordination with many providers, executing many instructions and recommendations |

| Emotional concerns | Giving up or loss of hope, diminished enthusiasm, worry, doubt, uncertainty | |

| Delays | Set backs in intervention |

Comorbid conditions delay or stall progress, unexpected events, hospitalizations |

| Lengthy appointments | Added inconvenience and risk during long waits, require planning to meet other health needs (e.g., diabetic snacks, medication doses, oxygen requirement) |

|

| Value of companion | Advocate | Bridging communication barriers, champion for unmet needs, providing morale support in an intimidating environment |

| Information support | Reminders, reinforcement, taking notes and asking questions | |

| Functional assistance | Transportation, help with technology, mobility assistance |

A complete list of quotations exemplifying each theme is available upon request.

Theme 1: Good Days, Bad Days

The theme good days, bad days reflects the fluctuating health status of people who have significant comorbidity and encompassed two attributes: physical and mental. For example, when a scheduled appointment fell on a bad day, physical symptoms related to concurrent health problems limited how much the individual gained from the intervention. One participant reported that it was difficult to “make it through” appointments when she was in pain, yet she was “not very with it” for the educational portions of the intervention when she used prophylactic pain medication. Other participants described having to cancel appointments on short notice when chronic symptoms flared:

“I have a problem with shortness of breath, and that day, it was just so bad I couldn’t make it.”

Similarly, respondents indicated that fluctuating health status produced inconsistency in their mental readiness for the intervention. When other health concerns eclipsed problems associated with low vision, participants’ energy and motivation waned. One companion explained that her husband had initially benefited from the intervention but then experienced an unrelated hospitalization that had “worn him down.” She hoped the success of low-vision rehabilitation would resume as he became “stronger mentally” and re-engaged.

Theme 2: Communication Barriers

A second theme was communication barriers, which were particularly problematic during the intervention’s educational components. Respondents framed communication barriers as specific to a participant’s impairment or related to nonconducive communication situations. Participants and companions described barriers due to hearing impairment. One companion articulated communication challenges associated with her mother’s cognitive impairment and her anticipation that clinicians would react negatively to this barrier:

“It’s going to be a challenge—she can understand, but things have to be repeated. … She can get it, but it’s just going to have to be on a level that it may be frustrating for whoever’s trying to help her do this.”

Some respondents attributed communication problems to the clinic environment or a provider’s delivery style. In these nonconducive situations, participants reported problems keeping up with rapid speech from providers and the “fast pace” of encounters. They described loud rooms crowded with people and devices, which could be distracting. Some communication barriers were attributed to a generation gap between patients and providers. One participant enjoyed the “good, energetic young people” on staff but noted that they spoke too softly and she wished they were more attentive to an “age barrier,” noting that, with age, “our processing time slows down.” One daughter described multifaceted communication and social barriers that diminished her mother’s experience:

“There are a lot of people involved. A lot of people talking at once. She couldn’t keep up. She wasn’t hearing everybody. Jokes were being made, and she wasn’t following, so she was sitting at her own appointment but feeling like she was an outsider …”

Theme 3: Overwhelmed

Participants indicated that their sense of being overwhelmed by comorbidity had two distinct attributes: pragmatic and emotional. Several participants gave concrete examples to illustrate the pragmatic challenges of participation in an intense, multicomponent intervention while balancing competing health demands.

“There are a lot of appointments sometimes that we have to get to, and I’m having a little bit of a problem getting time from work. It’s not just eye appointments—she has multiple appointments because she has multiple health problems. … I’m her only caregiver.”

When they felt emotionally overwhelmed by multiple health issues, respondents described “giving up.” One companion stated that her mother, who struggled with Sjogren’s disease and hearing loss, could not “get excited” about anything in the low-vision center because she felt overwhelmed by “everything” being affected, “her eyes, her hearing, her dry mouth.” The emotional attribute of “overwhelmed” was sometimes characterized by a sense of doubt about whether an intervention aimed at one problem would be beneficial when the individual’s limitations were multifactorial. For example, one participant noted that the low-vision clinic’s occupational therapist had proposed to help her sew again (a once-cherished hobby), but she felt doubtful:

“I would like to do that if I could, but I don’t know with my arthritis. I don’t think I could do that. Arthritis and vision both.”

Theme 4: Delays

The theme delays had two attributes related to comorbidity: (i) setbacks in the intervention due to unrelated medical problems and (ii) postponing attention to other medical problems because of intervention participation. The first attribute arose when acute and chronic health problems stalled progress of the longitudinal intervention. For example, fall-related injuries or unexpected hospitalizations created delays in executing recommendations from the low-vision clinic. In 13 cases, comorbid cataracts were a source of delay because cataracts are a potentially modifiable contributor to vision loss. When their macular disease specialist or general ophthalmologist referred individuals with cataracts, the rehabilitation team was forced to defer components of their intervention (e.g., prescriptions for new lenses, training on specific devices) until after a decision could be obtained about cataract removal.

In the second attribute, the lengthy clinical encounters and waiting times that often occurred in this multicomponent intervention were especially inconvenient for participants when they delayed attention to competing health needs, particularly time-sensitive needs, such as mealtimes for individuals with diabetes mellitus. Participants indicated that extra planning was required to accommodate their other health problems while receiving an intense health service intervention. For example, one participant noted, “next time, we’ll know to bring over lots more oxygen than just four hours’ worth.”

Theme 5: Value of Companion

Interviews suggested three companion roles that were potentially valuable for individuals with comorbidity: advocate, information support, and functional assistant. Some companions described themselves in an advocate role for individuals who had health conditions that limited their ability to gain full benefit from the intervention. For example, one companion reported,

“If I hadn’t been with her to remind people to please speak up and slow down or to look at her to talk to her, she may have missed more.”

Other companions indicated that participants depended on them to reconstruct important elements of the intervention later (information support). As such, the companions took notes or asked questions during the encounter and reinforced recommendations, particularly for individuals with comorbid memory deficit. In the words of one companion,

“I find myself reminding her, ‘Mom, please put your glasses on’; ‘Mom, where are your sun-glasses?’”

Companions also assisted with day-to-day functional needs related to the intervention, including transportation to clinic and setting up technological devices in the home. Although many participants expressed appreciation or gratitude for a companion’s presence at appointments, there were no vignettes from participants detailing specific benefits of companion involvement.

DISCUSSION

Mounting evidence suggests that the traditional, single-disease approach to health care—without sufficient attention to comorbidity—may fail to provide coordinated, cost-effective, or highest-quality care to the growing population of people with multiple conditions.3–5,28–30 Previous literature has focused on developing summary measures of comorbidity burden,31,32 quantifying the risks of comorbidity,28,33 accounting for comorbidity in medical decision-making34,35 and provision of primary care,16,36 or accommodating specific comorbid conditions such as depression.37 To the knowledge of the authors of the present study, this is the first study to employ a qualitative approach to categorize ways that coexisting conditions reduce the effectiveness of a targeted health service. Five general themes, drawn from participant and companion experiences, that provide a framework for accommodating comorbidity in a multicomponent intervention were identified (Table 3).

Table 3.

Implications of Comorbidity for Clinical Care and Comparative Effectiveness Research Involving Multi-component Interventions

| Theme and Representative Quote | Implications for Clinical Care | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Good Days, Bad Days “I said ‘Heavens, this is a bad day because I don’t ever take pain pills, and I thought I needed one today to sort of make it through.’ I said ‘I’m not very with it today.’” |

Flexibility in scheduling Same-day options Take-home materials or Web-based components Routine assessment of health status at each encounter plus appropriately individualized delivery |

Adaptive design Protocol to defer delivery of intervention components on “bad days” Protocol to defer assessing main outcomes on “bad days” Collect health status data at multiple time points |

| Communication Barriers “There are a lot of people involved. A lot of people talking at once. She couldn’t keep up. She wasn’t hearing everybody. Jokes were being made, and she wasn’t following, so she was sitting at her own appointment but feeling like she was an outsider I think somewhat.” |

Quiet rooms Minimal distraction Provider training in communication techniques Portable amplifiers Multiple modalities (graphic, video, audio, oral) |

Emphasis on communication barriers that may affect the consenting process |

| Overwhelmed “There are a lot of appointments sometimes that we have to get to, and I’m having a little bit of a problem getting time from work. But it’s not just eye appointments—she has multiple appointments because she has multiple health problems.” |

Synchronization with other health services Home visits Transportation services Protocols to acknowledge and elicit information about problems posed by comorbid conditions Support groups |

Appropriate incentives for participants and caregivers Minimize research-specific intrusions Coordination with medical services |

| Delays “I haven’t been able to go because I had a bad fall. I’ve been laid up. I haven’t been able to go get the new glasses.” |

Flexibility Screening referrals for common conditions that cause predictable delays Informing patient and caregiver in advance of expected arrival and departure times Accommodating comorbidity during long wait times (e.g., snacks for individuals with diabetes mellitus) |

Pilot studies to help anticipate patterns of delays and set appropriate exclusion criteria Outcome assessment at intervention completion rather than prespecified time intervals Power calculations that anticipate some individuals will not complete intervention during study period Supplemental analyses to estimate effectiveness among completers |

| Value of Companion “I find myself reminding her, ‘Mom, please put your glasses on’; ‘Mom, where are your sunglasses?’; ‘Mom, did you bring those magnifiers with you to help you?’” |

Protocols to engage companions Sessions and materials for companions |

Development of theory-driven strategies to maximize and evaluate the potential benefit of companion involvement Data collection on support network |

In these interviews, older adults and their companions discussed comorbidity—often without prompting—in nearly three-quarters of cases. Although the participants received a particular intervention (low-vision rehabilitation), the themes surrounding comorbidity are potentially applicable to other health service interventions, whether coordinated through subspecialty clinics or integrative primary care models. The themes suggest some items that clinicians and researchers interested in minimizing the effect of comorbidity on treatment success can act on. Higher comorbidity has been associated with worse self-reported satisfaction,38–40 and the framework presented here may offer a novel, systematic approach for improving satisfaction or measures of quality and benefit.

For example, providers might routinely ask a patient, “Health-wise, is this a good day or a bad day for you?” If the patient reports that health is worse than usual, it may be appropriate to postpone or shorten a planned intervention. Same-day scheduling may allow participants to receive more intervention on “good days.” To address common communication barriers, clinics may provide quiet settings, minimize distractions, or invest in portable amplifiers. Multimodal communication techniques such as written instructions, images, and audio messages may reduce barriers for some individuals. Features that maximize convenience, such as in-home visits, synchronization with other health services, or transportation, may benefit overwhelmed patients or caregivers. By screening referrals for treatable comorbidities that commonly interfere with an intervention, clinics may reduce avoidable delays. Subspecialty clinics may accommodate some coexisting conditions (such as offering snacks for people with diabetes mellitus) and provide accurate estimates of departure times so that individuals can properly plan for their other health needs during long appointments.

Finally, programs might consider protocols to actively identify and engage willing companions. Comments from companions were consistent with a previous finding that Medicare beneficiaries accompanied by an actively engaged companion were more satisfied with the clinical encounter, a relationship that was strongest in beneficiaries with the highest morbidity burden.41 The lack of corroboratory comments from participants in the current study may suggest that those who benefited most from companion support were less capable of recognizing or articulating their need. If so, it may be especially important to recruit companions for participants with particular comorbid conditions (e.g., cognitive impairment or affective disorders). Alternatively, participants may be less likely to perceive value if the companion provides support in a manner that the participant dislikes or resents. This explanation would be consistent with a previous finding that discrepancy in participant expectations and companion intentions largely explained participant dissatisfaction with companion involvement.42 Research is needed to develop strategies that maximize the potential benefit of companion involvement.

Several limitations may affect interpretation of these findings. First, participants who were receiving a specific intervention for a particular condition (macular disease), which primarily affects Caucasians, were interviewed. The generalizability of these participants’ experiences to other health services is uncertain. For example, cognitive impairment and hearing impairment may have a particularly detrimental effect on communication in this population because of synergistic effects with vision impairment. Second, the analysis included two perspectives (participant and companion), but qualitative data were not collected from providers or corroborated with medical records.

Nonetheless, these findings provide a foundation for future study concerning the effect of comorbidity within various health services. Interviews with older adults and companions revealed unmet needs and opportunities for better care. Although the findings highlight the pervasiveness and heterogeneity of comorbidity, the emergence of five themes implies that the diverse array of coexisting conditions affects patient experiences in ways that can be categorized. This study presents a novel framework that suggests practical steps for researchers and clinicians interested in addressing the complicated but critical problem of comorbidity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the participants and companions who shared their time, experiences, and opinions with investigators. We thank Gerald Mansell and Fay J. Tripp, who performed their roles as part of their regular duties and were not additionally compensated. We thank Dr. Eugene Oddone and Dr. Kenneth Schmader, who read earlier drafts of this manuscript and provided helpful insight.

Appendix A.

Semistructured Interview Guide.

| Participant | Interviewer Guide |

|---|---|

| Primary participant |

You have been participating in a low-vision rehabilitation program. You may have worked with a therapist or received some special devices to help with your vision problems. We are trying to understand ways that this program helps people and ways that it might be improved. |

| I’d like to ask you some questions about this and record your answers so that I can review them carefully later. May I record this next portion of our interview? |

|

| Start Recorder | |

| First, please tell me about any ways that this program helped you. Prompt for specifics, examples. | |

| Were there any challenges that you encountered during the rehab program? | |

| For each challenge named, prompt with, What might have helped with that? How could that have been made easier? | |

| Please tell me about any aspects of the rehab experience that were really helpful. Were there any things that were especially key to success? Prompt for specifics, examples. |

|

| In thinking about your experience in the low-vision rehabilitation clinic, were there any disappointments? | |

| For each disappointment named, prompt with What might have helped with that? | |

| Companion | Your (relationship to participant) has participated in a low-vision rehabilitation program. He/she may have worked with a therapist or received some special devices to help people with vision problems. We are trying to understand ways that this program helps people and ways that it might be improved. |

| I’d like to ask you some questions about this and record your answers so that I can review them carefully later. May I record this next portion of our interview? |

|

| Start Recorder | |

| First, please tell me about any ways that this program helped __ (participant’s name) ______. Prompt for specifics, examples. |

|

| Were there any challenges that he/she encountered during the rehab program? | |

| For each challenge named, prompt with, What might have helped with that? How could that have been made easier? | |

| Please tell me about any aspects of the rehab experience that were really key to helping __ (participant’s name) ______. Prompt for specifics, examples. |

|

| Were there any disappointments during __ (participant’s name) ______’s experience in low-vision rehab? | |

| For each disappointment named, prompt with What might have helped with that? |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper. The research was funded by National Institute on Aging Grants 5P30AG028716 and 5K23AG032867, and the John A. Hartford Foundation.

Author Contributions: HEW, HJC, SWC, DW: Study concept and design. HEW, DA, SWC, DW: Acquisition of participants or data. HEW, NA, LLS, SWC, KS, DW, HJC: Analysis and interpretation of data. HEW, KS, NA, SWC, DW, DA, LLS, HJC: Preparation of the manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: None of the sponsors participated in the design, methods, participant recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson GHJ. Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. September 2004 update. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Partnership for Solutions; Princeton, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson GF. Medicare and chronic conditions. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:305–309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb044133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parekh AK, Barton MB. The challenge of multiple comorbidity for the US health care system. JAMA. 2010;303:1303–1304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yancik R, Ershler W, Satariano W, et al. Report of the National Institute on Aging task force on comorbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62A:275–280. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:80–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:725–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1883–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stelmack JA, Tang XC, Reda DJ, et al. Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial (LOVIT) Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:608–617. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callahan LF. Physical activity programs for chronic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:177–182. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328324f8a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S97–S104. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, et al. Guided care for multimorbid older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:697–704. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: Will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009;301:2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stott DJ, Langhorne P, Knight PV. Multidisciplinary care for elderly people in the community. Lancet. 2008;371:699–700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owsley C, McGwin G, Jr., Lee PP, et al. Characteristics of low-vision rehabilitation services in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:681–689. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitson HE, Ansah D, Whitaker D, et al. Prevalence and patterns of comorbid cognitive impairment in low vision rehabilitation for macular disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010 Mar-Apr;50(2):209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.03.010. Epub 2009 May 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenhalgh T, Taylor R. Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) BMJ. 1997;315:740–743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holloway I. Basic Concepts for Qualitative Research. Blackwell Science, Ltd; Oxford: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt JSM, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neurosychiatr Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welsh K, Breitner JCS, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of dementia in the elderly using telephone screening of cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behavioral Neurol. 1993;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr., Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2870–2874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leff B, Reider L, Frick KD, et al. Guided care and the cost of complex healthcare: A preliminary report. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, et al. How to measure comorbidity. A critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:221–229. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00585-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: Prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, et al. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1839–1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Fried TR, et al. Health outcome priorities among competing cardiovascular, fall injury, and medication-related symptom outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1409–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyd CM, Reider L, Frey K, et al. The effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fung CH, Setodji CM, Kung FY, et al. The relationship between multimorbidity and patients’ ratings of communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:788–793. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0602-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Brick GW, et al. Clinical correlates of patient satisfaction after laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1155–1160. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kane RL, Maciejewski M, Finch M. The relationship of patient satisfaction with care and clinical outcomes. Med Care. 1997;35:714–730. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199707000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, et al. Patients’ perceptions of visit companions’ helpfulness during Japanese geriatric medical visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]