INTRODUCTION

In response to a request for proposal from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), our group was charged with developing non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic guidelines for treatments in gout that are safe and effective, i.e., with acceptable risk-benefit ratio. These guidelines for the management and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute attacks of gouty arthritis complements our manuscript on guidelines to treat hyperuricemia in patients with evidence of gout (or gouty arthritis) (1).

Gout is the most common cause of inflammatory arthritis in adults in the USA. Clinical manifestations in joints and bursa are superimposed on top of local deposition of monosodium urate crystals. Acute gout characteristically presents as self-limited, attack of synovitis (also called “gout flares”). Acute gout attacks account for a major component of the reported decreased health-related quality of life in patients with gout (2, 3). Acute gout attacks can be debilitating and are associated with decreased work productivity (4, 5).

Urate lowering therapy (ULT) is a cornerstone in the management of gout, and, when effective in lowering serum urate (SUA), is associated with decreased risk of acute gouty attacks (6). However, during the initial phase of ULT, there is an early increase in acute gout attacks, which has been hypothesized due to remodeling of articular urate crystal deposits as a result of rapid and substantial lowering of ambient urate concentrations (7). Acute gout attacks attributable to the initiation of ULT may contribute to non-adherence in long-term gout treatment, as reported in recent studies (8).

In order to systematically evaluate a broad spectrum of acute gouty arthritis, we generated multifaceted case scenarios to elucidate decision making based primarily on clinical and laboratory test-based data that can be obtained in a gout patient by both non-specialist and specialist health care providers in an office practice setting. This effort was not intended to create a novel classification system of gout, or new gout diagnostic criteria, as such endeavors are beyond the scope of this work.

Prior gout recommendations and guidelines, at the independent (i.e, non pharmaceutical industry-sponsored) national or multinational rheumatology society level, have been published by EULAR (9, 10), the Dutch College of General Practitioners (11), and the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR)(12). The ACR requested new guidelines, in view of the increasing prevalence of gout (13), the clinical complexity of management of gouty arthritis imposed by co-morbidities common in gout patients (14), and increasing numbers of treatment options via clinical development of agents(15–17). The ACR charged us to develop these guidelines to be useful for both rheumatologists and other health care providers on an international level. As such, this process and resultant recommendations, involved a diverse and international panel of experts.

In this manuscript, we concentrate on 2 of the 4 gout domains that the ACR requested for evaluation of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic management approaches: (i) analgesic and anti-inflammatory management of acute attacks of gouty arthritis, and (ii) pharmacologic anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute attacks of gouty arthritis. Part I of the guidelines focused on systematic non-pharmacologic measures (patient education, diet and lifestyle choices, identification and management of co-morbidities) that impact on hyperuricemia, and made recommendations on pharmacologic ULT in a broad range of case scenarios of patients with disease activity manifested by acute and chronic forms of gouty arthritis, including chronic tophaceous gouty arthropathy(1). Each individual and specific statement is designated as a “recommendation”, in order to reflect the non-prescriptive nature of decision making for the hypothetical clinical scenarios.

So that the voting panel could focus on gout treatment decisions, a number of key assumptions were made, as described in Part I of the guidelines (1). Importantly, each proposed recommendation assumed that correct diagnoses of gout and acute gouty arthritis attacks had been made for the voting scenario in question. For treatment purposes, it was also assumed that treating clinicians were competent, and considered underlying medical comorbidities (including diabetes, gastrointestinal disease, hypertension, and hepatic, cardiac, and renal disease), and potential drug toxicities and drug-drug interactions, when making both treatment choicesand dosing decisions on chosen pharmacologic interventions. The RAND/UCLA methodology used here emphasizes level of evidence, safety, and quality of therapy, and excludes analyses of societal cost of health care. As such, the ACR gout guidelines are designed to reflect best practice, supported either by level of evidence or consensus-based decision-making. These guidelines cannot substitute for individualized, direct assessment of the patient, coupled with clinical decision making by a competent health care practitioner. The motivation, financial circumstances, and preferences of the gout patient also need to be considered in clinical practice, and it is incumbent on the treating clinician to weigh the issues not addressed by this methodology, such as treatment costs, when making management decisions. Last, the guidelines for gout management presented herein were not designed to determine eligibility for health care cost coverage by third party payers.

METHODS

Utilizing the RAND/UCLA methodology (18), we conducted a systematic review, generated case scenarios, developed recommendations, and graded the evidence.

Design: RAND/ UCLA Appropriateness Method overview

The RAND/UCLA method of group consensus was developed in the 1980s, incorporates both Delphi and nominal group methods (18), and has been successfully used to develop other guidelines commissioned by the ACR. The purpose of this methodology is to reach a consensus among experts, with an understanding that published literature may not be adequate to provide sufficient evidence for day-to-day clinical decision-making. The RAND/UCLA method requires 2 groups of experts—a core expert panel (CEP) that provides input into case scenario development, and a task force panel (TFP) that votes on the case scenarios (1) Systematic review of pertinent literature was performed concurrently, and a scientific evidence report was generated. This evidence report was then given to the TFP, in conjunction with clinical scenarios representing each question of interest.

The diverse TFP, totaling11 people, consisted of rheumatologists in community private practice (C King), HMO practice (G Levy), and VA practice (G Kerr), a rheumatology physician-scientist inflammation researcher(B Roessler), a rheumatologist with expertise in clinical pharmacology(D Furst), a rheumatologist gout expert that is an Internal Medicine Residency Director (NL Edwards), a rheumatologist gout expert that is a Chair of Internal Medicine (B Mandell), 2 primary care internal medicine physicians (D Jones, S Yarows), a nephrologist (V Niyyar), and a patient representative (S Kaplan)(1). There were 2 rounds of ratings, the first, anonymously, with the members of the TFP instructed to rank each potential element of the guidelines on a risk-benefit Likert scale ranging from 1 to 9, followed by a face-to-face group discussion with re-voting. A vote of 1–3 on the Likert scale was scored as Inappropriate where risks clearly outweigh the benefits. A vote of 4–6 on the Likert scale was scored Uncertain(“lack of consensus”) where the risk-benefit ratio is uncertain. A vote of 7–9 on the Likert scale was scored as Appropriate where benefits clearly outweigh the risks. Case scenarios were translated into recommendations where the median voting scores were 7–9 on the Likert scale (“appropriate”), and if there was no significant disagreement, defined as no more than 1/3 of the TFP voting below the Likert scale level of 7 in the question. The final rating was done anonymously in a 2-day face-to-face meeting led by an experienced internal medicine physician moderator (NWenger).

Systematic review

PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched to find all articles on gout with help of an experienced librarian (RO). PubMed is a database of medical literature from the 1950s to the present. CENTRAL includes references from PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Review Groups’ specialized registers of controlled trials and hand search results. We used search terminology (hedge) based on the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials. The hedge was expanded to include articles discussing research design, cohort, case control and cross sectional studies. Limits added to the hedge include English Language and the exclusion of “animal only” studies. The searches for all 4 domains were conducted simultaneously and therefore included terms for hyperuricemia and other gout-related issues. Conducted on 9/25/10, the search retrieved 5,380 articles from PubMed and CENTRAL. The review was divided into three stages: titles, abstracts from manuscripts, and the entire manuscripts. At each stage, each title, abstract or manuscript was included or excluded using pre-specified rules, as described (1). Of the 5,830 titles, 192 duplicate titles and 82 non-English titles were excluded, with an additional 3,729 titles excluded based on exclusion criteria – leaving 1,827 titles of which another 1,699 were excluded in the abstract phase. A total of 128 manuscripts remained that were further categorized into pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic studies (1). Subsequently, we updated our systematic review by repeating the search with the same criteria, to include any articles that were published between 9/25/10-3/31/11, and we hand searched recent meeting abstracts from the American College of Rheumatology and EULAR for any randomized controlled trials that were yet to be published. The supplemental search resulted in 4 additional manuscripts, and 5 meeting abstracts on pharmacologic agents, some of which were subsequently published and then re-evaluated for evidence grade. Finally, there were 41 manuscripts on non-pharmacologic modalities (such as diet, alcohol, exercise, etc.) that included both retrospective and prospective studies, but all were excluded, since none were randomized, controlled studies on interventions in gout patients. There were 87 manuscripts on pharmacologic agents for the treatment of patients with gout. Of these 47 were randomized controlled trials and included in the evidence report; whereas the remaining 40 uncontrolled trials were excluded. A total of 21 manuscripts on ULT were separately addressed (1). For this paper (Part II of the Guidelines), a total of 30 manuscripts and 5 meeting abstracts were assessed, with 26 manuscripts and 2 meeting abstracts on acute gout, and 4 manuscripts and 3 meeting abstracts on prophylaxis included in the evidence report and evaluated by the TFP.

Case Scenarios

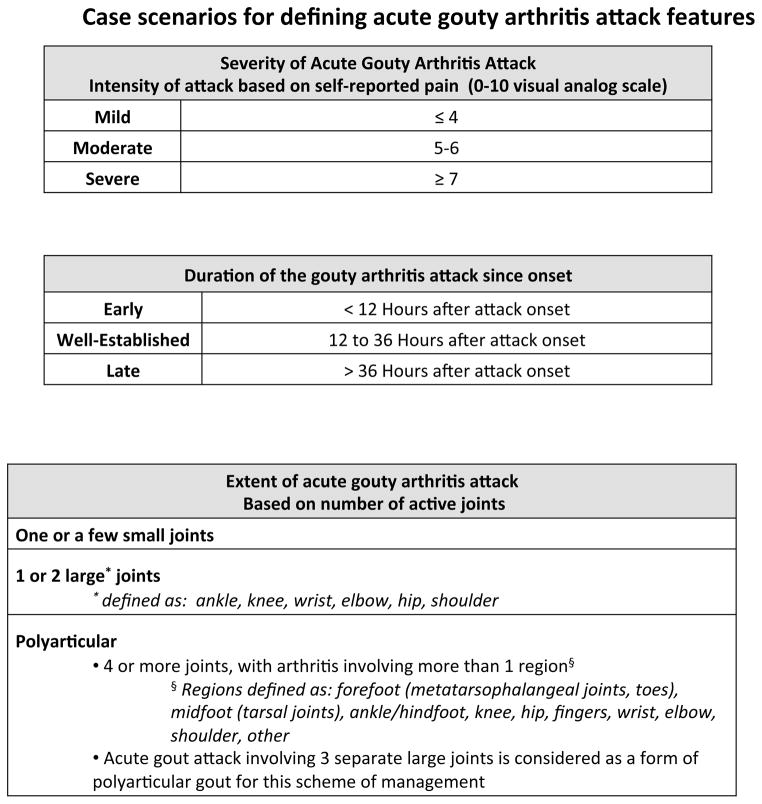

Through an interactive, interactive process the CEP developed unique case scenarios of acute gouty attacks with varied treatment options, and type of attack by severity, duration and extent of attack. The objective was to represent a broad spectrum of attacks that a clinician might see in a busy practice. For the case scenarios, severity of acute gout differed varied based on self-reported worst pain on a 0–10 visual analog scale(19, 20). Pain ≤ 4 was considered mild, 5–6 was considered moderate, and ≥ 7 was considered severe(19, 20). Case scenarios also varied by duration of the acute gout attack; divided this into early (< 12 hours), well established (12–36 hours), and late (> 36 hours). Case scenarios also varied in the number of active joints involved—one or 2–3 small joints, one or two large joints (ankle, knee, wrist, elbow, hip, or shoulder), and polyarticular involvement (defined as either (a) acute arthritis involving 3 separate large joints, or (b) acute arthritis of 4 or more joints, with arthritis involving more than 1 “region” of joints). Joint “regions” were defined as: forefoot (metatarsal joints and toes), midfoot (tarsal joints), ankle/hindfoot, knee, hip, fingers, wrist, elbow, shoulder, other (Figure 1). The management strategies presented were developed for case scenarios involving gouty arthritis, but the intent was that acute bursal inflammation due to gout (e.g., in the prepatellar or olecranon bursa) and small joint involvement would have comparable recommendations for overall management strategies.

Figure 1. Case scenarios for defining acute gouty arthritis attack features.

These case scenarios were generated by the CEP, and therapeutic decision making options for these scenarios were voted on by the TFP.

Developing recommendations from votes by the TFP, and grading the evidence

A priori, recommendations were derived from only positive results (median Likert score ≥ 7). In the following results section, all recommendations derived from TFP votes are denoted by an accompanying evidence grade. In addition to TFP vote results, the panel provided some statements based on discussion (not votes). Such statements are specifically described as discussion items (rather than TFP-voted recommendations) in the results section. We also comment on specific circumstances where the TFP did not votea particularly important clinical decision making item as appropriate (i.e. median Likert score was ≤ 6, or wide dispersion of votes despite a median score of ≥ 7). Samples of voting scenarios and results are presented in Supplemental Figure 1.

The level of evidence supporting each recommendation was ranked based on previous methods used by the American College of Cardiology (21) and applied to other recent ACR recommendations (22, 23): Level A grading was assigned to recommendations supported by more than one randomized clinical trials, or one or more meta-analyses; Level B grading was assigned to the recommendations derived from a single randomized trial, or nonrandomized studies; Level C grading was assigned to consensus opinion of experts, case studies, or standard-of-care.

Managing perceived potential conflict of interest (COI)

Potential COI was managed in a prospective and structured manner (1). All participants intellectually involved in the project, whether authors or not, were required to fully disclose their relationships with any of the companies with a material interest in gout, listed in the appendix. Disclosures were identified as the start of the project and updated every 6 months. A summary listing of all perceived potential COI is available in the supplemental material.

Based on the policies of the ACR, no more than 49% of project participants were permitted to have COI at any given time, and a majority of the TFP was required to have no perceived potential COI. It was further required that the project PI (JFitzgerald) remain without perceived potential COI during the guideline development process, and for an additional 12 months afterwards.

RESULTS

General principles for treatment of the acute attack of gouty arthritis (“acute gout” management)

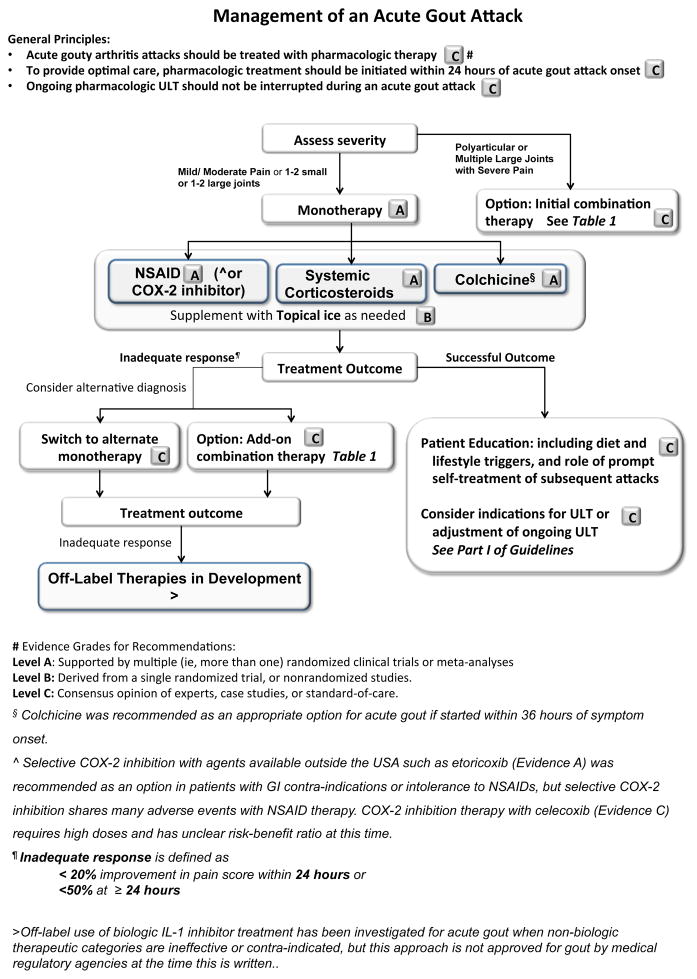

Figure 2 summarizes the overall recommendations on treatment of an acute gouty arthritis attack. The TFP recommended that an acute gouty arthritis attack should be treated with pharmacologic therapy (Evidence C), and that treatment should be preferentially initiated within 24 hours of onset of an acute gout attack (Evidence C). The latter recommendation was based on consensus that early treatment lead to better patient reported outcomes. The TFP also recommended to continue established pharmacologic ULT without interruption, during an acute attack of gout (Evidence C); ie, do not stop ULT therapy during an acute attack. The TFP also recommended patient education, not simply on dietary and other triggers of acute gout attacks, but also providing the patients with instruction so that they can initiate treatment upon signs and symptoms of an acute gout attack, without need to consult their health care practitioner for each attack (Evidence C).

Figure 2. Overview of management of an acute gout attack.

This algorithm summarizes the recommendations by the TFP on the overall approach to management of an acute attack of gouty arthritis, with further details, as expanded in other figures and tables, referenced in the figure, and discussed in the text.

Initial pharmacologic treatment of the acute attack of gouty arthritis

The TFP recommended that choice of pharmacologic agent should be based upon severity of pain and the number of joints involved (Figure 2). For attacks of mild/moderate gout severity (≤ 6/10 on a 0–10 pain VAS) involving 1–3 small joints or 1–2 large joints, the TFP recommended that initiating monotherapy was appropriate, with recommended options being oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), systemic corticosteroids, or oral colchicine (24–27) (Figure 2) (Evidence A for all therapeutic categories). The TFP also voted that combination therapy was appropriate when the acute gout attack was characterized by severe pain in a polyarticular attack (Evidence C). The TFP did not rank one therapeutic class over another. Therefore, it is at the discretion of the prescribing physicians to choose the most appropriate monotherapy based on the patient’s preference, prior response to pharmacologic therapy for an acute gout attack, and associated comorbidities. Recommendations for appropriate combination therapy options are highlighted in Table 1, and discussed below. The TFP did not vote on case scenarios for specific renal or hepatic function impairment-adjusted dosing and individual contraindications, or drug-drug interactions, with pharmacologic therapies (28–30).

Table 1.

TFP recommendations for combination therapy approach to acute gouty arthritis

|

NSAIDs

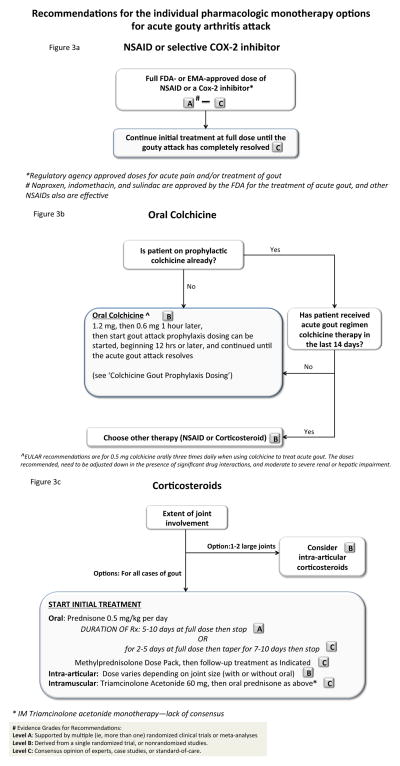

For NSAIDs, the TFP recommended full dosing at either the Food and Drug Administration or the European Medical Agency approved anti-inflammatory/analgesic doses used for the treatment of acute pain and/or treatment of acute gout (Evidence A–C) (26, 27, 31–33) (Figure 3a). The FDA has approved naproxen (Evidence A) (33, 34), indomethacin (Evidence A) (26, 27, 31, 32), and sulindac (Evidence B) (35) for the treatment of acute gout. However, analgesic and anti-inflammatory doses of other NSAIDs may be as effective (Evidence B–C). For COX-2 inhibitors, as an option in patients with GI contra-indications or intolerance to NSAIDs, published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support efficacy of etoricoxib (Evidence A), and lumiracoxib (Evidence B), (24, 36, 37), but these agents are not available in the USA, and lumiracoxib has been withdrawn from use in several countries due to hepatotoxicity. A single comparison celecoxib vs. indomethacin RCTpreviously presented in abstract form at the ACRhas not yet been published, but suggested effectiveness of a high dose celecoxib regimen (800 mg once, followed by 400 mg on day 1, then 400 mg twice daily for a week) in acute gout. The TFP recommended this celecoxib regimen as an option for acute gout in carefully selected patients with contra-indications or intolerance to NSAIDs (Evidence C), keeping in mind that risk-benefit ratio is not yet clear for celecoxib in acute gout.

Figure 3. Recommendations for the individual pharmacologic monotherapy options for an acute gouty arthritis attack.

The Figure is separated into distinct parts that schematize use of the first line therapy options (NSAIDs, corticosteroids, colchicine), and specific recommendations by the TFP.

The TFP did not reach a consensus to preferentially recommend any one specific NSAID as first line treatment. The TFP did recommend continuing the initial NSAID inhibitor treatment regimen at full dose (if appropriate) until the acute gouty attack completely resolved (Evidence C). The option to taper the dose in patients with multiple comorbidities/ hepatic or renal impairment was reinforced by the TFP, without specific TFP voting or more prescriptive guidance. Last, there was no TFP consensus on the use of intramuscular ketorolac or topical NSAIDs for the treatment of acute gout.

Colchicine

The TFP recommended oral colchicine as one of the appropriate primary modality options to treat acute gout, but only for gout attacks where the onset was no greater than 36 hours prior to treatment initiation (Evidence C; Figure 3b). The TFP recommended that acute gout can be treated with a loading dose of 1.2 mg of colchicine followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later (10) (Evidence B), and this regimen can then followed by gout attack prophylaxis dosing 0.6 mg once or twice daily (unless dose adjustment is required) 12 hours later, until the gout attack resolves (Evidence C) (25). For countries where 1.0 mg or 0.5 mg rather than 0.6 mg tablets of colchicine are available, the TFP recommended, as appropriate, 1.0 mg colchicine as loading dose, followed by 0.5 mg 1 hour later, and then followed as needed, after 12 hours, by continued colchicine (up to 0.5 mg three times daily) until the acute attack resolves (Evidence C). In doing so, the TFP rationale was informed by pharmacokinetics of the low dose colchicine regimen, where the exposure to drug in plasma becomes markedly reduced ~12 hours after administration in normal, healthy volunteers (25). The TFP also evaluated prior EULAR recommendations on a colchicine dosing regimen for acute gout (0.5 mg three times daily), and the BSR-recommended maximum dosage for acute gout of 2 mg colchicine per day(10,12).

The algorithm in Figure 3b outlines recommendations for colchicine based on FDA labeling and TFP deliberations and votes, including specific recommendations for patients already on colchicine acute gout attack prophylaxis. For more specific prescriptive guidance, practitioners should consult the FDA-approved drug labeling, including recommended dosing reductionin moderate to severe CKD (38), and colchicine dose reduction (or avoidance of colchicine use) with drug interactions with moderate to high potency inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 and of P-glycoprotein; major colchicine drug interactions include those with clarithromycin, erythromycin, cyclosporine, and disulfiram (29,30). Last, the TFP did not vote on use of intravenous colchicine, since the formulation is no longer available in the USA, due to misuse and associated severe toxicity.

Systemic and intra-articular corticosteroids, and ACTH

When selecting corticosteroids as the initial therapeutic, the TFP recommended to first consider the number of joints with active arthritis. For involvement of 1–2 joints, the TFP recommended the use of oral corticosteroids (Evidence B); the TFP additionally recommended the option of intra-articular corticosteroids for acute gout of 1–2 large joints (Evidence B; Figure 3c) (39). For intra-articular corticosteroid therapy in acute gouty arthritis, it was recommended that dosing be based on the size of the involved joint(s), and that this modality could be used in combination (Table 1) with oral corticosteroids, NSAIDs, or colchicine (Evidence B) (39). Specific doses for intra-articular corticosteroid therapy in specific joints were not considered during TFP voting.

Where intra-articular joint injection is impractical (e g. polyarticular joint involvement, patient preference, or injection is not in the scope of provider’s usual practice) the TFP recommended oral corticosteroids, prednisone or prednisolone at a starting dose of at least 0.5 mg/kg per day for 5–10 days, followed by discontinuation (Evidence A) (27, 40); or alternately 2–5 days at full dose, followed by tapering for 7–10 days, and then discontinuation (Evidence C). Acknowledging current prevalence of usage, the TFP recommended, as an appropriate option according to provider and patient preference, the use of an oral methylprednisolone dose pack for initial treatment of an acute attack of gout (Evidence C).

The TFP also recommended as appropriate, in each case scenario, an alternative regimen of intramuscular single dose (60 mg) triamcinolone acetonide, followed by oral prednisone or prednisolone (Evidence C). However, there was no consensus by the TFP on the use of intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide as monotherapy. Last, the TFP vote also did not reach a consensus on use of ACTH (Evidence A)for acute gout in patients able to take medications orally, but did consider ACTH in separate voting, described below, for patients unable to take oral anti-inflammatory medications.

Initial combination therapy for acute gout

For patients with severe acute gout attack (≥ 7/10 on 0–10 pain VAS), and patients with an acute polyarthritis or involvement of more than one large joint, the TFP recommended, as an appropriate option, the initial simultaneous use, of full doses (or where appropriate, full dose of one agent and prophylaxis dosing of the other) of two of the pharmacologic modalities recommended above. Specifically, the TFP recommended the option to use combinations of colchicine and NSAIDs, oral corticosteroids and colchicine, or intra-articular steroids with any of the other modalities (Evidence C). The TFP was not asked by the CEP to vote on use of NSAIDs and systemic corticosteroids in combination, given CEP concerns about synergistic gastrointestinal tract toxicity of that drug combination.

Inadequate response of an acute gout attack to initial therapy

There is lack of a uniform definition of an inadequate response to the initial pharmacologic therapy for an acute attack of gouty arthritis (2, 25, 41). Clinical trials in acute gout have defined variable primary endpoints for therapeutic response, such as percentage improvement in pain on a Likert or visual analogue scale. To define inadequate response for scenarios in this section, the CEP asked the TFP to vote on various percent improvement definitions at time points such as 24, 48, or 72 hours. The TFP voted that the following criteria would define inadequate response of acute gout to pharmacologic therapy in case scenarios: either, < 20% improvement in pain score within 24 hours, or <50% improvement in pain score ≥ 24 hours after initiating pharmacologic therapy.

For the scenario of a patient with an acute attack of gouty arthritis not responding adequately to initial pharmacologic monotherapy, the TFP advised, without a specific vote, that alternative diagnoses to gout should be considered (Figure 2). For patients not responding to initial therapy, the TFP also recommended switching to another monotherapy recommended above (Evidence C) or adding a second recommended agent (Evidence C). Use of a biologic IL-1 inhibitor (anakinra 100 mg subcutaneously daily for 3 consecutive days (Evidence B)(41,42), or canakinumab 150 mg subcutaneously (43,44)as an option for severe attacks of acute gouty arthritis refractory to other agents was graded as Evidence A in the systematic review. Given lack of randomized studies for anakinra (41,42), and unclear risk-benefit ratio and lack of FDA approval for canakinumab (43,44)at the time this is written, the authors, independent of TFP discussion, assessed the role of IL-1 inhibitor therapy in acute gout as uncertain.

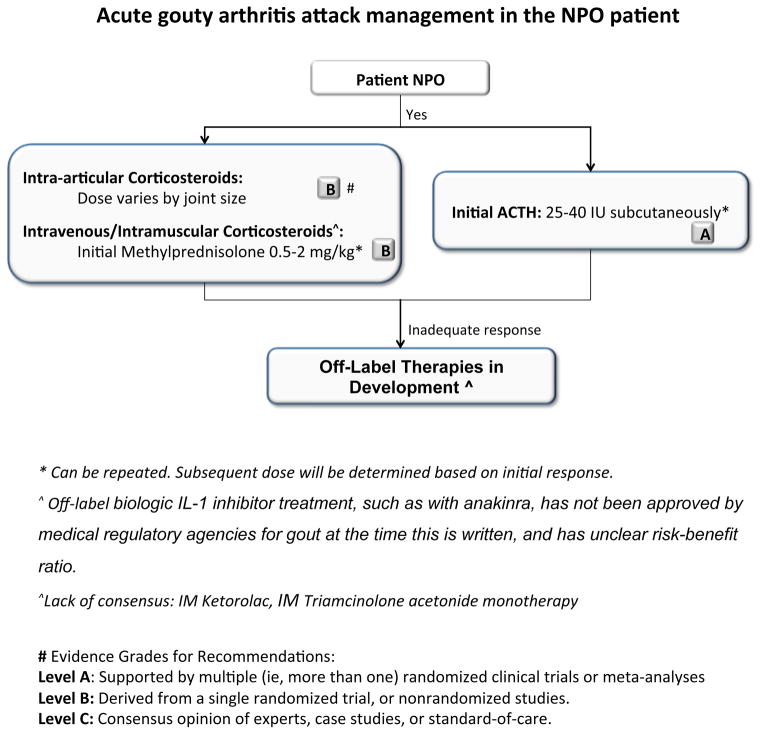

Case Scenarios for the NPO (nil per os [nothing by mouth]) Patient

Acute gout attacks are common in the in-hospital setting, where patients may be NPO due to different surgical and medical conditions. In such a scenario, the TFP recommended intra- articular injection of corticosteroids for involvement of 1–2 joints (with dose depending on the size of the joint; Evidence B; Figure 4)(39). The TFP also recommended, as appropriate options, intravenous or intramuscular methylprednisolone at an initial dose at 0.5–2.0 mg/kg (Evidence B) (45).

Figure 4. Acute gouty arthritis attack management in the nil per os (NPO) patient.

The Figure schematizes options for management of acute gout in the patient unable to take oral anti-inflammatory medications, and specific recommendations by the TFP on decision making in this setting.

The TFP also recommended, as an appropriate alternative for the NPO patient, subcutaneous synthetic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) at an initial dose of 25–40 IU (Evidence A) (46), with repeat doses as clinically indicated (for either ACTH or intravenous steroid regimens). There was no voting by the TFP on specific follow-up ACTH or intravenous steroid dosing regimen, given lack of evidence. In the scenario of the NPO patient with acute gout, there was no consensus on the use of intramuscular ketorolac or intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide monotherapy. Biologic IL-1 inhibition therapy remains an FDA unapproved modality for NPO patients, without specific past evaluation in this population.

Critical drug therapy adverse event considerations in acute gout

It was not possible to evaluate every permutation of gout treatment and comorbid disease given the constraints of the project. The treating clinician will need to carefully weigh the complexities of each unique patient. TFP discussions emphasized that potential drug toxicities due to co-morbidities and drug-drug interactions are considerable in treatment of acute gout (29,30). Some examples include underlying moderate and severe CKD (NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, colchicine), congestive heart failure (NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors), peptic ulcer disease (NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, corticosteroids), anticoagulation or anti-platelet aggregation therapy (NSAIDs), diabetes (corticosteroids), ongoing infection or high risk of infection (corticosteroids), and hepatic disease (NSAIDs. COX-2 inhibitors, colchicine) (29, 30).

Complementary therapies for acute gout attack

The TFP recommended topical ice application to be an appropriate adjunctive measure to one or more pharmacologic therapies for acute gouty arthritis (Evidence B) (47). The TFP voted, as inappropriate, the use of a variety of oral complementary agents for the treatment of an acute attack (cherry juice or extract, salicylate-rich willow-bark extract, ginger, flaxseed, charcoal, strawberries, black currant, burdock, sour cream, olive oil, horsetail, pears, or celery root).

RECOMMEDATIONS FOR PHARMACOLOGIC ANTI-INFLAMMATORY PROPHYLAXIS OF ATTACKS OF ACUTE GOUT

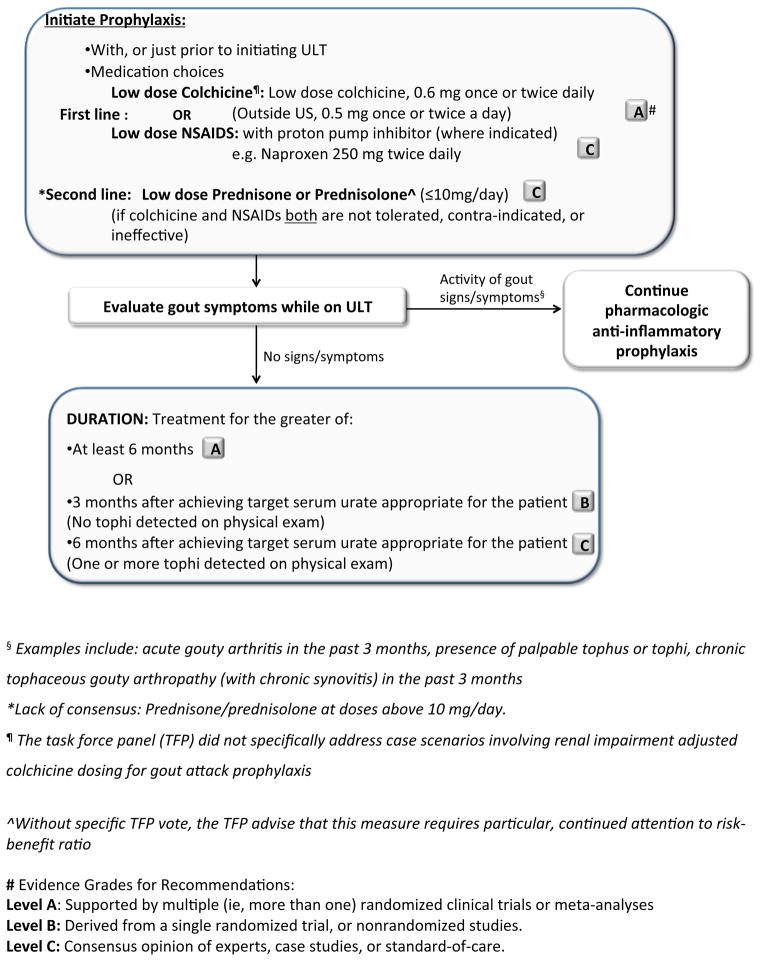

The TFP recommended pharmacologic anti-inflammatory prophylaxis for all case scenarios of gout where ULT was initiated, given high gout attack rate frequencies in early ULT (Evidence A; Figure 5) (48–51). For gout attack prophylaxis, the TFP recommended use, as a first line option, of oral colchicine (51,52) (Evidence A). The TFP also recommended, as a first line option (with a lower evidence grade than for colchicine, the use of low dose NSAIDs (such as naproxen 250 mg orally twice a day), with proton pump inhibitor therapy or other effective suppression therapy for peptic ulcer disease and its complications, where indicated (Evidence C) (51).

Figure 5. Pharmacologic anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of gout attacks, and its relationship to pharmacologic ULT.

The Figure provides an algorithm for use of anti-nflammatory prophylaxis agents to prevent acute gout attacks. The schematic highlights specific recommendations by the TFP on decision making on the initiation, options, and duration of prophylaxis relative to pharmacologic ULT therapy, relative to achievement of the treatment objectives of ULT.

In their evaluation of colchicine evidence in gout attack prophylaxis, the TFP specifically recommended low dose colchicine (0.5 mg or 0.6 mg orally once or twice a day, with dosing further adjusted downwards for moderate to severe renal function impairment and potential drug-drug interactions)(29) as appropriate for gout attack prophylaxis. The TFP did not vote on specific quantitative renal function impairment-adjusted dosing of oral colchicine. Since a pharmacokinetic analysis suggesting colchicine dose should be decreased by 50% below a creatinine clearance of 50 is unpublished at the time this is written, specific quantitative colchicine dose adjustment in CKD is the decision of the treating clinician.

The TFP, in discussion without a specific vote, recognized the evidence that colchicine and low dose NSAID prophylaxis fail to prevent all gout attacks in patient populations after initiation of ULT (48–51). As an alternative gout attack prophylaxis strategy in patients with intolerance or contra-indication or refractoriness to both colchicine and NSAIDs, the TFP recommended use of low dose prednisone or prednisolone (defined here as ≤10 mg/day) (Evidence C). Nevertheless, concerns were raised in discussion, amongst the TFP and by the other authors, regarding particularly sparse evidence for efficacy of this low dose strategy. Given the known risks of prolonged use of corticosteroids, the authors urge clinicians to be particularly attentive in reevaluating risk-benefit ratio of continued corticosteroid prophylaxis as the risk of acute gout attack decreases with time in conjunction with effective ULT. The TFP voted the use of high daily doses (i.e., above 10 mg daily) of prednisone or prednisolone for gout attack prophylaxisto be as inappropriate in most case scenarios, and there waslack of TFP consensus for more severe forms of chronic tophaceous gouty arthropathy. Last, there was a lack of TFP consensus on risk-benefit ratio for off-label use of biologic IL-1 inhibition (Evidence A) (53,54) for anti-inflammatory gout attack prophylaxis in patients who previously failed or had intolerance or contra-indications to low doses of colchicine, NSAIDs, and prednisone or prednisolone for gout attack prophylaxis.

Duration of anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gout attacks

The TFP recommended to continue pharmacologic gout attack prophylaxis if there is any clinical evidence of continuing gout disease activity (such as one or more tophi detected on physical exam, recent acute gout attacks, or chronic gouty arthritis), and/or the serum urate target has not yet been achieved (1). Specifically, the TFP voted to continue the prophylaxis for the greater of: (i) six months duration (Evidence A) (48,50,51); or (ii) three months after achieving target serum urate for the patient without tophi detected on physical exam, (Evidence B); or (iii) six months after achieving target serum urate, where there has been resolution of tophi previously detected on physical exam (Evidence C)(Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Acute attacks of gout have a detrimental impact on quality of life of the patient due to pain and dysfunction of affected joints, and acute gout can have a substantial economic and societal impact (55–57). Following a systematic review of the literature, and use of a formal group assessment process, we provide the first ACR guidelines for the therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gout attacks.

The TFP recommended multiple modalities (NSAIDs, corticosteroids by different routes, and oral colchicine) as appropriate initial therapeutic options for acute gout attacks. The TFP was informed in part by recent direct comparison studies suggesting rough equivalency of oral systemic corticosteroids with NSAIDs (27, 40). Essentially, the TFP concluded, without a specific vote, that selection of treatment choice is that of the prescribing clinician, and to be based upon factors including patient preference, the patient’s previous response to pharmacologic therapies, associated comorbidities, and, in the unique case of colchicine, the time since onset of the acute gout attack. The dosing adjustments and relative and absolute contra-indications for NSAIDs and colchicine due to associated comorbidities (such as renal and hepatic impairment) and drug interactions were not addressed in these guidelines. There is published literature addressing these issues (29,30), including quality indicators for safe use of NSAIDs (58–60), including ACR quality indicators for treatment of gout (61).

The TFP recommended a novel set of strict limitation on colchicine doses for acute gout, starting with no more than 1.8 mg over 1 hour in the first 12 hour period of treatment (Evidence B) (25), a paradigm shift from widespread prior use of this drug in clinical practice (10,12), but in accordance with FDA guidance. Prior EULAR and BSR recommendations on colchicine dosing for acute gout (10,12), and colchicine low dose regimen pharmacokinetics (25) informed the TFP recommendation of low dose colchicine (at a maximum of 0.6 mg twice daily) as a continuation option for an acute gout attack, if started at least 12 hours following the initial low dose regimen.

For patients with polyarticular joint involvement, and severe presentations of gout in 1–2 large joints, the TFP recommended, as appropriate, certain first-line combination therapy approaches. Although there is a lack of published RCT data to support these recommendations, a large survey of rheumatologists in USA has illustrated that combination therapy for acute gout is often employed (62).

With respect to anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gout attacks, low-dose colchicine, or low dose NSAIDs, were recommended as acceptable first line options by the TFP, with a higher evidence level for colchicine. The use of low-dose colchicine or an NSAID in gout attack prophylaxis is also recommended by the EULAR (10). To date, in small clinical trials, low dose daily oral colchicine was effective in preventing acute gout attacks (3,52), with supportive post hoc analyses in ULT trials (51). Efficacy of low dose NSAIDs for gout attack prophylaxis also was described in the febuxostat clinical trial program (51); however prophylaxis was not the primary focus of the trials. Importantly, recent clinical trials of ULT agents have shown substantial rates of acute gout attacks in the first few 6 months after the initiation of ULT, even when prophylaxis with colchicine 0.6 mg daily or low dose NSAID therapy is administered (48–51). It is noteworthy that the TFP recommended prednisone or prednisolone ≤10 mg daily as a second line option for acute gout prophylaxis, with the caveat that there is a lack of published robust data for use of low-dose oral prednisone for gout prophylaxis. More investigation is needed to improve management for this clinical problem. Assessment of modulation of cardiovascular event risks by colchicine prophylaxis or by NSAIDs (63) in gout patients would be particularly informative.

Limitations of the recommendations presented in this manuscript include that only ~30% were based on level A evidence, with approximately half based on level C evidence; this indicates the need for more studies in the aspects of gout management considered here. The process used here was limited by the current trial designs for assessment of acute gout therapies and prophylaxis of anti-inflammatory pharmacological agents in gout. For acute gout studies, most studies were on NSAIDs and involved an active comparator and non-inferiority trial design. However, the majority of these studies failed to provide a non-inferiority margin, which needs to be defined a priori to assess the validity of these trials. Although the majority of studies assessed pain as the primary outcome for the acute gout trials, there is a lack of a single uniform measure, which precludes meta-analysis. Furthermore, there is lack of consensus on what time period after initiation of therapy constitutes a primary response, since trials ranged from few hours to 10 days. With the exception of recent analyses of biologic IL-1 inhibitors (53,54), there was a lack of robust clinical trials of gout attack prophylaxis using anti-inflammatory pharmacologic agents. Also, the primary measure in these trials is the recurrence of self-reported acute gout attacks, an outcome that has not been validated using OMERACT criteria (64). Efforts are underway to precisely define acute gout attack in gout clinical trials (65). Last, the RAND/UCLA methodology did not address important societal and patient preference issues on treatment costs and cost-effectiveness comparisons between medication choices for acute gout and pharmacologic prophylaxis of acute gout attacks. This is already a pressing question with respect to use of agents including colchicine, COX-2 selective inhibitors, and ACTH, and would be expected to emerge as a larger issue if biologic IL-1 inhibitors, in late stage clinical development after phase III studies at the time this written, obtain regulatory approval for acute gout treatment and prophylaxis.

In summary, these guidelines, the first from the ACR for the management and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute attacks of gouty arthritis, have been developed to provide recommendations to clinicians treating patients with gout. The ACR plans to update these guidelines to capture future treatments or advances in the management and prophylaxis of acute gout, and as the risk-benefit ratios of emerging therapies are further investigated.

Addendum

Therapies that were approved after the original literature review are not included in these recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

An acute gouty arthritis attack should be treated with pharmacologic therapy, initiated within 24 hours of onset

Established pharmacologic ULT should be continued, without interruption, during an acute attack of gout

NSAIDs, corticosteroids, or oral colchicine are appropriate first line options for treatment of acute gout, and certain combinations can be employed for severe or refractory attacks

Pharmacologic anti-inflammatory prophylaxis is recommended for all gout patients when pharmacologic urate-lowering is initiated, and should be continued if there is any clinical evidence of continuing gout disease activity and/or the serum urate target has not yet been achieved

Oral colchicine is appropriate first-line gout attack prophylaxis therapy, including with appropriate dose adjustment in chronic kidney disease and for drug interactions, unless there is lack of tolerance or medical contra-indication

Low dose NSAID therapy is an appropriate choice for first-line gout attack prophylaxis, unless there is lack of tolerance or medical contra-indication

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Amy Miller and Ms. Regina Parker of the ACR for administrative support and guidance. Drs. Jennifer Grossman (UCLA), Michael Weinblatt (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School), Ken Saag (UAB) and Ted Ganiats (UCSD) provided valuable guidance on the objectives and process. Rikke Ogawa (UCLA) provided greatly appreciated service as medical research librarian.

FUNDING:

This project was entirely funded by a grant from the American College of Rheumatology.

Supported by a Grant from the American College of Rheumatology

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or reviewing or revising the intellectual content of the work, and all authors approved the final version of the paper submitted for publication. Drs. Dinesh and Puja Khanna, John FitzGerald, and Robert Terkeltaub each had full access to all of the data in the study and each take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Study conception and design. Dinesh Khanna, Puja Khanna, TuhinaNeogi, Michael Pillinger, Joan Merrill, Susan Lee, H. Ralph Schumacher, Mark Robbins, John FitzGerald, Robert Terkeltaub.

Acquisition of data. Dinesh Khanna, Puja Khanna, John FitzGerald, Robert Terkeltaub.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Dinesh Khanna, Puja Khanna, John FitzGerald, Robert Terkeltaub

Author conflict of interests are provided directly from the American College of Rheumatology and detailed separately.

Contributor Information

Dinesh Khanna, Email: Khannad@med.umich.edu.

Puja P. Khanna, Email: PKhanna@med.umich.edu.

John D. FitzGerald, Email: jfitzgerald@mednet.ucla.edu.

Manjit K. Singh, Email: manjitksingh@gmail.com.

Sangmee Bae, Email: sbae04@gmail.com.

Tuhina Neogi, Email: tneogi@bu.edu.

Michael H. Pillinger, Email: mhpillinger@gmail.com.

Joan Merill, Email: Joan-Merrill@omrf.org.

Susan Lee, Email: s2lee@ucsd.edu.

Shraddha Prakash, Email: SPrakash@mednet.ucla.edu.

Marian Kaldas, Email: MKaldas@mednet.ucla.edu.

Maneesh Gogia, Email: MGogia@mednet.ucla.edu.

Fernando Perez-Ruiz, Email: fperezruiz@telefonica.net.

Will Taylor, Email: william.taylor@otago.ac.nz.

Frédéric Lioté, Email: Frederic.liote@lrb.aphp.fr.

Hyon Choi, Email: hchoi@partners.org.

Jasvinder A. Singh, Email: jasvinder.md@gmail.com.

Nicola Dalbeth, Email: n.dalbeth@auckland.ac.nz.

Sanford Kaplan, Email: SK616@aol.com.

Vandana Niyyar, Email: vniyyar@emory.edu.

Danielle Jones, Email: danielle.jones@emory.edu.

Steven A. Yarows, Email: steven_yarows@ihacares.com.

Blake Roessler, Email: roessler@umich.edu.

Gail Kerr, Email: Gail.Kerr@va.gov.

Charles King, Email: cking@nmhs.net.

Gerald Levy, Email: gerald.d.levy@kp.org.

Daniel E. Furst, Email: DEFurst@mednet.ucla.edu.

N. Lawrence Edwards, Email: edwarnl@medicine.ufl.edu.

Brian Mandell, Email: MANDELB@ccf.org.

H. Ralph Schumacher, Email: schumacr@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Mark Robbins, Email: Mark_Robbins@vmed.org.

Neil Wenger, Email: nwenger@mednet.ucla.edu.

Robert Terkeltaub, Email: rterkeltaub@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Khanna D, FitzGerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh M, Neogi N, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for Management of Gout Part I: Systematic Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Therapeutic Approaches to Hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/acr.21772. (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, McCredie M, Brooks PM, Jones M. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med. 1987;17:301–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1987.tb01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, Klinenberg JR, Bluestone R. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout. A placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609–14. doi: 10.1002/art.1780170517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook RA, Forsythe A, Smeeding JE, Edwards NL. Chronic gout: epidemiology, disease progression, treatment and disease burden. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:2813–21. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.533647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards NL, Sundy JS, Forsythe A, Blume S, Pan F, Becker MA. Work productivity loss due to flares in patients with chronic gout refractory to conventional therapy. J Med Econ. 2011;14:10–5. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.540874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:321–5. doi: 10.1002/art.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker MA, MacDonald PA, Hunt BJ, Lademacher C, Joseph-Ridge N. Determinants of the clinical outcomes of gout during the first year of urate-lowering therapy. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27:585–91. doi: 10.1080/15257770802136032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:437–43. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, Bardin T, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: Diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1301–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1312–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romeijnders AC, Gorter KJ. Summary of the Dutch College of General Practitioners’ “Gout” Standard. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, Zhang W, Doherty M, Secki J, et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1372–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41. doi: 10.1002/art.30520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichikawa N, Taniguchi A, Urano W, Nakajima A, Yamanaka H, et al. Comorbidities in patients with gout. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30:1045–50. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.596499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richette P, Ottaviani S, Bardin T. New therapeutic options for gout. Presse Med. 2011;40:844–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terkeltaub R. Update on gout: new therapeutic strategies and options. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:30–8. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang LP. Oral colchicine (Colcrys): in the treatment and prophylaxis of gout. Drugs. 2010;70:1603–13. doi: 10.2165/11205470-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brook R. Methodology Perspectives, AHCPR 1994. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones KR, Vojir CP, Hutt E, Fink R. Determining mild, moderate, and severe pain equivalency across pain-intensity tools in nursing home residents. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:305–14. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.05.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, Hubbard R, Snabes M, Palmer SN, et al. Lessons learned from a multiple-dose post-operative analgesic trial. Pain. 2004;109:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–e235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman JM, Gordon R, Ranganath VK, Deal C, Caplan L, Chen W, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1515–26. doi: 10.1002/acr.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacher HR, Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, Mukhopadhyay S, Malmstrom K, Ng J, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ. 2002;324:1488–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7352.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW, et al. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060–8. doi: 10.1002/art.27327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alloway JA, Moriarty MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:111–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swarup A, Sachdeva N, Schumacher HR., Jr Dosing of Antirheumatic Drugs in Renal Disease and Dialysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2004;10:190–204. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000135555.83088.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Digiacinto JL, Kook KA, Davis MW. Novel evidence-based colchicine dose-reduction algorithm to predict and prevent colchicine toxicity in the presence of cytochrome P450 3A4/P-glycoprotein inhibitors. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2226–37. doi: 10.1002/art.30389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keenan RT, O’Brien WR, Lee KH, Crittenden DB, Fisher MC, Goldfarb DS, et al. Prevalence of contraindications and prescription of pharmacologic therapies for gout. Am J Med. 2011;124:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1422–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cattermole GN, Man CY, Cheng CH, Graham CA, Rainer TH. Oral prednisolone is more cost-effective than oral indomethacin for treating patients with acute gout-like arthritis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16:261–6. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32832a083f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maccagno A, Di Giorgio E, Romanowicz A. Effectiveness of etodolac (‘Lodine’) compared with naproxen in patients with acute gout. Curr Med Res Opin. 1991;12:423–9. doi: 10.1185/03007999109111513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sturge RA, Scott JT, Hamilton EB, Liyanage SP, Dixon AS, Davies J, Engler C. Multicentre trial of naproxen and phenylbutazone in acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 1977;36:80–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.36.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karachalios GN, Donas G. Sulindac in the treatment of acute gout arthritis. Int J Tissue React. 1982;4:297–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, Antigua J, Londono J, Pryhuber KG, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:598–606. doi: 10.1002/art.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willburger RE, Mysler E, Derbot J, Jung T, Thurston H, Kreiss A, et al. Lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily is comparable to indomethacin 50 mg three times daily for the treatment of acute flares of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1126–32. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.FDA prescribing information for COLCRYS. 2009 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022351lbl.pdf.

- 39.Fernandez C, Noguera R, Gonzalez JA, Pascual E. Treatment of acute attacks of gout with a small dose of intraarticular triamcinolone acetonide. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2285–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60799-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen K, Fields T, Mancuso CA, Bass AR, Vasanth L. Anakinra’s efficacy is variable in refractory gout: report of ten cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:210–4. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlesinger N, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A, Yucel AE, Richard D, Murphy V, et al. Canakinumab relieves symptoms of acute flares and improves health-related quality of life in patients with difficult-to-treat Gouty Arthritis by suppressing inflammation: results of a randomized, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R53. doi: 10.1186/ar3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.So A, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A, Yucel AE, Richard D, Murphy V, et al. Canakinumab for the treatment of acute flares in difficult-to-treat gouty arthritis: Results of a multicenter, phase II, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3064–76. doi: 10.1002/art.27600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groff GD, Franck WA, Raddatz DA. Systemic steroid therapy for acute gout: a clinical trial and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1990;19:329–36. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(90)90070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD005521. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005521.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlesinger N, Detry MA, Holland BK, Baker DG, Beutler AM, Rull M, et al. Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, Streit J, Joseph-Ridge N. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundy JS, Baraf HS, Yood RA, Edwards NL, Gutierrez-Urena SR, Treadwell EL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Espinoza LR, Wells AF, MacDonald P, Lloyd E, Lademacher C. The urate-lowering efficacy and safety of febuxostat in the treatment of the hyperuricemia of gout: the CONFIRMS trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R63. doi: 10.1186/ar2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Jackson RL. Effect of prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: analysis of data from three phase III trials. Clin Ther. 2010;32:2386–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, Scroogie DA, Harris MD, Alloway JA. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schumacher HR, Jr, Sundy JS, Terkeltaub R, Knapp HR, Mellis SJ, Stahl N, et al. Rilonacept (interleukin-1 trap) in the prevention of acute gout flares during initiation of urate-lowering therapy: results of a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:876–84. doi: 10.1002/art.33412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schlesinger N, Mysler E, Lin HY, De Meulemeester M, Rovensky J, Arulmani U, et al. Canakinumab reduces the risk of acute gouty arthritis flares during initiation of allopurinol treatment: results of a double-blind, randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1264–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brook RA, Kleinman NL, Patel PA, Melkonian AK, Brizee TJ, Smeeding JE, Joseph-Ridge N. The economic burden of gout on an employed population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1381–9. doi: 10.1185/030079906X112606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kleinman NL, Brook RA, Patel PA, Melkonian AK, Brizee TJ, Smeeding JE, Joseph-Ridge N. The impact of gout on work absence and productivity. Value Health. 2007;10:231–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khanna P, Khanna D. Health-related quality of life and outcome measures in gout. In: Terkeltaub R, editor. Gout and other crystal arthropathies. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2011. pp. 217–25. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saag KG, Olivieri JJ, Patino F, Mikuls TR, Allison JJ, MacLean CH. Measuring quality in arthritis care: the Arthritis Foundation’s quality indicator set for analgesics. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:337–49. doi: 10.1002/art.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fravel MA, Ernst ME. Management of gout in the older adult. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Risser A, Donovan D, Heintzman J, Page T. NSAID prescribing precautions. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:1371–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mikuls TR, MacLean CH, Olivieri J, Patino F, Allison JJ, Farrar JT, et al. Quality of care indicators for gout management. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:937–43. doi: 10.1002/art.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schlesinger N, Moore DF, Sun JD, Schumacher HR., Jr A survey of current evaluation and treatment of gout. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2050–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Gonzalez-Perez A, Bueno H, Hwa J. NSAID use selectively increases the risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction: a systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grainger R, Taylor WJ, Dalbeth N, Perez-Ruiz F, Singh JA, Waltrip RW, et al. Progress in measurement instruments for acute and chronic gout studies. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2346–55. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gaffo AL, Schumacher HR, Saag KG, Taylor WJ, Dinnella J, Outman R, et al. Developing a provisional definition of a flare in patients with established gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 doi: 10.1002/art.33483. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.