Hybrid transvaginal endoscopic surgery can be facilitated with additional instruments, techniques, and a flexible endoscope. Magnets are an aid to exposure using a laparoscopic rein.

Keywords: Magnets, Culdolaparoscopy, Liver, Laparoscopy, NOTES

Abstract

Introduction:

A novel technique was used to remove a large liver cyst via culdolaparoscopy.

Case Description:

We used laparoscopic instruments, a gastroscope, a laparoscopic rein, and magnets. The magnets consist of an external magnet and a specially modified tethered neodymium internal magnet, safe for use in transvaginal endoscopic surgery.

Discussion:

These technologies offer some advantages when they are used together: magnets and the rein to aid in exposure, traction–retraction, and triangulation. Previous reports have been published on the removal of benign liver lesions transvaginally, but none to date has involved the use of magnets. This article reports on the role of magnets and reins in an incision reduction approach to the removal of a liver cyst.

INTRODUCTION

A transvaginal approach with assisted minilaparoscopy in the removal of benign liver lesions has previously been reported in the surgical literature. In one case, culdolaparoscopy with a liver biopsy was an incidental finding1; the other 2 cases reported2 and the case here presented were programmed liver cyst interventions. We used laparoscopy reins and a magnetic grasper in single-port laparoscopy surgery and in transvaginal cholecystectomies.3,4 The transvaginal approach is a safe method with better aesthetic results than prior laparoscopic procedures we had performed, resulting in less patient discomfort and potential risk for abdominal incision site hernias. The initial findings of this approach in the removal of hepatic benign lesions look promising.

CASE REPORT

The surgery was performed in May 2008 at Hospital Regional, Poza Rica, SESVER in Veracruz, Mexico after being approved by the Institutional Review Board for Minilaparoscopy Assisted Natural Orifice Surgery (MANOS) and Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) using rigid, flexible, and magnetic technologies, with Dr. Fausto Davila as the principal investigator.5 A 32-y-old multiparous female with a body mass index of 35 presented with right upper-quadrant abdominal pain and jaundice. Additional sonogram and computed tomography scan findings showed a simple liver cyst measuring 12.2cm by 12.3cm. Preoperative laboratory results showed a total bilirubin of 9.29 mg/dL (normal, 0.3 to 1.9) a direct bilirubin of 6.86 mg/dL (normal, 0 to 0.3), an alanine transaminase (ALT; serum glutamic pyruvate transaminase [SGPT]) of 116 IU/L (normal, 7 to 56), and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST; serum glutamic oxalacetic transaminase [SGOT]) of 85 IU/L (normal, 5 to 40). The elevated bilirubin was due to pressure from a large simple cyst over the biliary tract. The patient was given a dedicated informed consent for this procedure and was scheduled for surgery after risk and benefits were carefully explained, as was done in previous operations.6 She received intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis with metronidazole and cephalosporins and had undergone bowel preparation starting the night before the procedure. The procedure was done with the patient under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. The patient was placed in the European position for laparoscopy. In the operating room, one monitor was placed by the patient's right shoulder, the other by her left foot. The vagina was cleansed with 10% povidone iodine; pelvic examination was done while the patient was anesthetized to assess the pelvis for mobility and potential for obstruction of the posterior cul-desac. After placing a Foley catheter in the urinary bladder, a uterine manipulator (ZUMI-4.5; Circon Cabot, Racine, WI) was inserted, and a weighted vaginal speculum was used to allow proper exposure of the posterior fornix. Pneumoperitoneum was induced with a Verses needle inserted in the umbilical area. The 5-mm umbilical port was placed and a 5-mm laparoscope with camera was inserted. The posterior cul-desac was visualized with the laparoscope. A plastic, 12-mm diameter, 15-cm long armed trocar was placed against the posterior fornix. The weighted speculum was removed and the uterine manipulators together with the trocar were pushed upward and anteriorly. The point of pressure was identified with the laparoscope, and under laparoscopic surveillance, the trocar was inserted into the posterior cul-desac. The armed trocar was removed and the external cannula remained as a vaginal port.7 A set of magnets was used that consisted of a larger external magnet and a smaller intraabdominal magnet, which was an 11 mm in diameter neodymium magnet with an alligator grasper in tandem and an alligator clip applier (IMANLAP, Buenos Aires, Argentina). This intraabdominal magnet was modified with a tether of 0 polypropylene suture, 75cm long. The intraabdominal magnet was introduced via the vaginal port with a Maryland grasper. The free end of the tether remained outside the vaginal port and was held with a Kelly clamp. The external magnet was placed inside a sterilized Ziploc bag. The bagged magnet was introduced into a sterilized tubular stockinet. The stockinet was closed at both ends with knots. The external magnet was used to attract the intraabdominal magnet to the anterior peritoneum in the pelvis. The surgeon then moved the internal magnet by sliding the external magnet along the patient's abdomen (Figure 1). The magnet was brought to the designated area of the anterior abdominal wall near the cyst and was kept in place.4 A gastroscope (Excera GIF-160 Olympus, Center Valley, PA) was introduced into the abdominal cavity for visualization through the vaginal port with the patient in the Trendelenburg position. The gastroscope was brought to the umbilical line, approximately 10cm away from the liver, and the patient's position was changed into a reverse Trendelenburg for better visualization. The umbilical port was used to place a 5-mm laparoscope and instruments, e.g., laparoscopic scissors, needle holder, and aspiration needle, as well as a rein. The rein consisted of a straight, 6-cm, cutting-edge needle, 2-0 polypropylene (Prolene, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) 75cm in length with a stoppage at the end made of silastic, measuring 3 × 2x1mm.7

Figure 1.

The external magnet inside a tubular stockinet.

While viewing the cyst from the vaginal port with a gastroscope, an aspiration needle was placed via the umbilical port for drainage. After the collapse of the cyst wall, an alligator clip applier was used to grasp the back of the alligator clamp attached to the internal neodymium magnet, opening its jaws and grasping the cyst. The internal magnet and the external magnet were then coupled and moved to the desired location by sliding the external magnet along the skin. This technique allowed for retraction of the cyst wall while keeping it under tension (Figure 2). With this exposure, the roof of the cyst was removed using a 5-mm laparoscopy scissor placed in the umbilical port. The rein was introduced into the abdomen via a 5-mm umbilical port. Once the abdomen was accessed, the needle was passed through the cyst wall at the strategic point with relation to the internal magnet to provide better exposure and triangulation. The rein was held as a marionette or at the skin level to anchor the cyst with a Kelly clamp. The rein needle was cut and disposed of safely (Figure 3).7 The removed portion of the cyst was brought to the pelvic area by using the magnets for mobilization. The laparoscopy rein held the specimen as a marionette while allowing traveling from the upper abdomen to the pelvis. A 5-mm laparoscope was placed in the umbilical port. A 10-mm laparoscopic clamp was placed via the vaginal port to grab the specimen. The external magnet was removed. The Kelly clamps holding the end of the tether and the end of the rein were released and in a coordinated manner, the specimen, the magnet, the rein, and the vaginal port were removed together vaginally (Figure 4). The vaginal port was reintroduced to place a catheter for drainage in the right upper flank. The colpotomy incision was closed with 2-0 chromic sutures placed vaginally. Two hours after surgery the patient was sitting, eating, and with pain of 2cm as measured on her visual analogue scale. Thirty-six hours after surgery, her jaundice began to clear, the total bilirubin was 3.2 mg/dL, the direct bilirubin was 2.1 mg/dL, the ALT (SGPT) was 59 IU/L, the AST (SGOT) was 24 IU/L and the vaginal drainage was removed. She was discharged 2 d after surgery, which is customary in this hospital for laparoscopic cholecystectomies. She resumed sexual activities 40 d after surgery without dyspareunia. She was followed for 1 wk and 3 mo after surgery she had no complications.

Figure 2.

Tethered magnet holding the cyst wall.

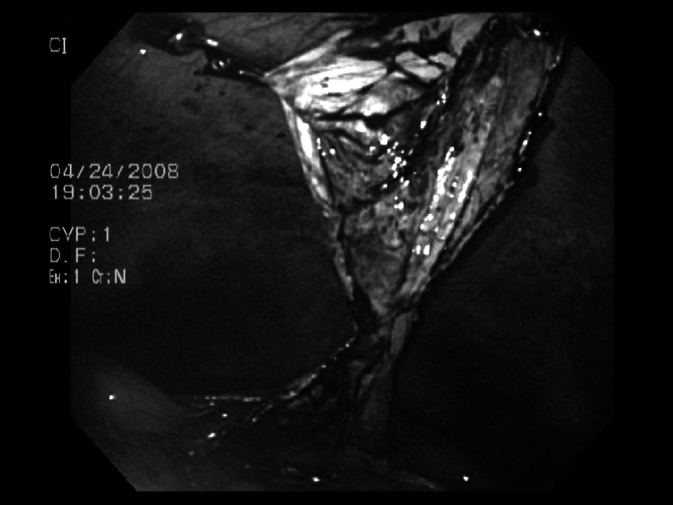

Figure 3.

A magnet, rein exposure.

Figure 4.

Transvaginal magnet and cyst wall extraction.

DISCUSSION

Hybrid transvaginal endoscopic surgery can be facilitated with additional instruments, techniques, and a flexible video endoscope. Retraction and exposure are done with magnets and a laparoscopic rein, instead of using additional abdominal ports, which lead to added patient discomfort and unnecessary scaring.7 Magnets have been investigated for their use in the transvaginal approach.3,8,9 The magnets are used through a natural orifice to retract tissues by aligning them with external magnets to avoid additional trocar placement.10 The function of the tether is to localize an out-of-sight or dislodged intraabdominal magnet. The tether should not be used indiscriminately, because pulling may cause injury to adjacent tissues.3 Although the rein can move the target in one direction, the magnet has the option in most cases to move freely via the anterior peritoneum, and the ability to reposition the graspers offers a range of movements beyond the rein. Secured independent tools (SIT) not used in this case are different from the rein; the SIT provides more range of movement without target perforation but has less mobility than the magnets.11 The use of 2 magnets creates a risk of collision of the internal or external magnets; we avoid this event in our approach by combining one set of magnets with a rein.

CONCLUSION

We modified an internal laparoscopic magnet grasper by adding a 75-cm tether. This change was originally recommended for transvaginal cholecystectomies as a way to secure or retrieve the internal magnet in case of misplacement during natural orifice surgery. The tether is left inside the vaginal port, held externally, and removed with the magnet at the end of the procedure. Furthermore, the use of the laparoscopy rein in combination with magnets avoids the risk of collision when more than one internal or external set of magnets is used. The cumulative experience in culdolaparoscopy, a hybrid transvaginal endoscopic surgery, suggests benefits with less pain, fewer hernias, and definitely better cosmetics results. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the use of magnets for the transvaginal treatment of a liver cyst in humans. This concept has the potential to change the way we approach minimally invasive surgery in the abdomen by using different instruments or techniques and combining them with the use of magnets.

Contributor Information

Daniel Alberto Tsin, The Mount Sinai Hospital of Queens. Long Island City, NY, USA..

Guillermo Dominguez, Fundación Hospitalaria, Buenos Aires, Argentina..

Fausto Davila, Sesver Regional Hospital, Poza Rica City, Veracruz, Mexico..

Juan Manuel Alonso-Rivera, Sesver Regional Hospital, Poza Rica City, Veracruz, Mexico..

Brad Safro, The Mount Sinai Hospital of Queens. Long Island City, NY, USA..

Andrea Tinelli, Vito Fazzi General Hospital, Lecce, Italy..

References:

- 1. Tsin DA, Bumaschny E, Helman M, et al. Culdolaparoscopic oophorectomy with vaginal hysterectomy: an optional minimal-access surgical technique. J Laparoendoscope Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12:269–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castro-Pérez R, Dopico-Reyes E, Acosta-González LR. Minilaparoscopic-assisted transvaginal approach in benign liver lesions. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102(6):357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsin DA, Dominguez G, Jesus R, Aguilar S, Davila F. Transvaginal cholecystectomy using magnetic graspers. Paper presented at: 37th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists; October 28-November 1, 2008; Las Vegas, NV [Google Scholar]

- 4. Padilla BE, Dominguez G, Millan C, Martinez-Ferro M. The use of magnets with single-site umbilical laparoscopic surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2011;20(4):224–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davila FJ, Tsin DA, Gutierrez LS, Lemus J, Jesus R, Davila MR, Torres-Morales J. Transvaginal single port cholecystectomy surgical laparoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(3):203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsin DA, Tinelli A, Malvasi A, Davila F, Jesus R, Castro-Perez R. Laparoscopy and natural orifice surgery: first entry safety surveillance step. JSLS. 2011;15(2):133–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsin DA, Davila F, Dominguez G, Tinelli A. Laparoscopy rein and a backward needle entrance. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21(6):521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park S, Bergs RA, Eberhart R, Baker L, Fernandez R, Cadeddu JA. Trocar-less instrumentation for laparoscopy: magnetic positioning of intra-abdominal camera and retractor. Ann Surg. 2007;245:379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho YB, Park CM, Chun HK, et al. Transvaginal endoscopic cholecystectomy using a simple magnetic traction system. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2011;20(3):174–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott DJ, Tang S, Fernandez R, et al. Completely transvaginal NOTES cholecystectomy using magnetically anchored instruments. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2308–2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsin DA, Davila F, Dominguez G, Manolas P. Secured independent tools in peritoneoscopy. JSLS. 2010;14:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]