Abstract

Climatic and environmental shifts have had profound impacts on faunal and floral assemblages globally since the end of the Miocene. We explore the regional expression of these fluctuations in southwestern Europe by constructing long-term records (from ∼11.1 to 0.8 Ma, late Miocene–middle Pleistocene) of carbon and oxygen isotope variations in tooth enamel of different large herbivorous mammals from Spain. Isotopic differences among taxa illuminate differences in ecological niches. The δ13C values (relative to VPDB, mean −10.3±1.1‰; range −13.0 to −7.4‰) are consistent with consumption of C3 vegetation; C4 plants did not contribute significantly to the diets of the selected taxa. When averaged by time interval to examine secular trends, δ13C values increase at ∼9.5 Ma (MN9–MN10), probably related to the Middle Vallesian Crisis when there was a replacement of vegetation adapted to more humid conditions by vegetation adapted to drier and more seasonal conditions, and resulting in the disappearance of forested mammalian fauna. The mean δ13C value drops significantly at ∼4.2−3.7 Ma (MN14–MN15) during the Pliocene Warm Period, which brought more humid conditions to Europe, and returns to higher δ13C values from ∼2.6 Ma onwards (MN16), most likely reflecting more arid conditions as a consequence of the onset of the Northern Hemisphere glaciation. The most notable feature in oxygen isotope records (and mean annual temperature reconstructed from these records) is a gradual drop between MN13 and the middle Pleistocene (∼6.3−0.8 Ma) most likely due to cooling associated with Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

Introduction

Profound paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic events in the late Cenozoic affected life on Earth and gave rise to modern climate regimes and biomes. Progressive cooling, which began in the middle Miocene (14-13.8 Ma), ultimately led to the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation ∼2.7 Ma [1]–[3]. This cooling was not monotonic, however. For example, reorganized ocean circulation, perhaps associated with initial restriction of circulation between the Pacific and Atlantic, contributed to the Pliocene Warm Period between ∼4.7 and 3.1 Ma [4]. Shifts in temperature and ocean circulation were associated with shifts in the global water budget, though impacts varied by region. Furthermore, terrestrial environments were transformed from the end of the Miocene to the beginning of the Pliocene (∼8-3 Ma) by the worldwide expansion of C4 plants [5]–[6]. C4 plants evolved repeatedly from C3 plants, most likely as a response to low atmospheric pCO2, higher temperatures and increasing water-stress [7].

In southern Europe, our focus here, tectonic closure of the Mediterranean Basin reduced circulation from the Atlantic, likely exascerbated by a drop in sea level associated with increased Antarctic ice volume, culminating with the formation of thick evaporite deposits (Messinian Salinity Crisis or MSC) between ∼6.0 and 5.3 Ma [8]–[9].

As one of the few locations in southern Europe with a relatively complete (albeit low resolution) late Cenozoic stratigraphic succession, a number of recent investigations have reconstructed regional paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental conditions on the Iberian Peninsula. Based on the bioclimatic analysis of Plio-Pleistocene fossil rodent assemblages, Hernández Fernández et al. [10] argued there was a cooling trend, from subtropical temperatures in the early Pliocene to temperate conditions for the rest of the studied period. Study of palynological records from different Iberian sections led Jiménez-Moreno et al. [11] to suggest that warm temperatures of the Early to Middle Miocene gave way to progressively cooler temperatures in the remainder of Miocene and Pliocene. By the end of the Pliocene and beginning of the Pleistocene, the Iberian palynological record showed the development of steppes, coincident with cooler and drier conditions at the start of glacial-interglacial cycles in the Northern Hemisphere. Van Dam [12] investigated precipitation rates in the Iberian Peninsula using micro-mammal community structure. The most striking features are a decrease of mean annual precipitation (MAP) in the beginning of the Late Miocene (∼11−8.5 Ma), an increase in MAP in the middle part of the Late Miocene (∼8.5−6.5 Ma) and a drop in MAP between the end of the Late Miocene and the Late Pliocene (∼6.5−3 Ma). Böhme et al. [13] reconstructed MAP using herpetological assemblages between the end of the Early Miocene and the Early Pliocene in the Calatayud-Daroca Basin. Their MAP record differed from that of van Dam [12], with an increase in MAP at the beginning of the Late Miocene (∼11−9.7 Ma), a sharp decrease at ∼ 9.7 Ma, a progressive increase in MAP up to the middle Late Miocene (∼8.3 Ma) and a gradual decrease until the beginning of the Pliocene (∼5.4 Ma).

Mammalian tooth enamel is a reliable source of isotopic data that can be used to explore past environmental and climatic changes. Here, the stable carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of fossil tooth enamel from different genera of herbivorous mammals spanning from late Miocene to middle Pleistocene (∼11.1-0.8 Ma) were analyzed. Our objectives are twofold: 1) to infer the paleoecology of the selected taxa over the study interval, and 2) to reconstruct paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic trends in Iberia from the late Miocene to the middle Pleistocene.

Materials and Methods

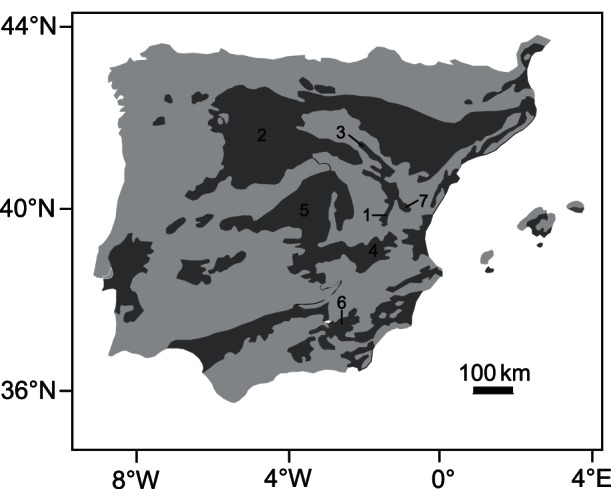

The Iberian Cenozoic basins (Fig. 1) were formed as a consequence of Alpine compression between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates [14]–[15]. Most of the basins are located on basement comprising Precambrian and Paleozoic metasediments or granitoids and Mesozoic detrital and carbonate rocks. These basins constitute 40% of the total surface area of the Iberian Peninsula and they offer a complete sedimentary record that spans most of the Cenozoic. Most fossil sites selected for this study (La Roma 2, Masía de la Roma 604B, Puente Minero, Los Mansuetos, Cerro de la Garita, El Arquillo 1, Las Casiones, Milagros, La Gloria 4) are in the Teruel Basin in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. The name, age and taxonomic composition for localities in the Teruel Basin and other Neogene and Quaternary sites are supplied in Table 1.

Figure 1. Situation of the studied fossil sites.

Cenozoic basins of the Iberian Peninsula (dark grey) and situation of the basins where the fossil sites are located. 1–Teruel Basin, 2–Duero Basin, 3–Calatayud-Daroca Basin, 4–Cabriel Basin, 5–Tajo Basin, 6–Guadix-Baza Basin, 7–Sarrión-Mijares Basin.

Table 1. Site, basin, MN, age (Ma) and taxa from this study.

| Site | Basin | MN | Age (Ma) | Equus stenonis | Mammuthus meridionalis | Elephas antiquus | Anancus arvernensis | Zygolophodon turicensis | Tetralophodon longirostris | Gomphotherium angustidens | Undetermined Gomphotheriidae | Gazella borbonica | aff. Gazella sp. nov. | Gallogoral meneghini | Gazellospira torticornis | cf. Hesperidoceras merlae | Protoryx sp. | Tragoportax amalthea | Tragoportax ventiensis | Tragoportax gaudryi | Tragoportax sp. | Hispanodorcas torrubiae | Undetermined Bovidae | Croizetoceros ramosus | Eucladoceros senezensis | Croizetoceros pyrenaicus | Pliocervus turolensis | Turiacemas concudensis | Palaeoplatyceros hispanicus | Undetermined Cervidae | Birgerbohlinia schaubi | Microstonyx major | |

| Huéscar 1 | Guadix-Baza | MP | 0.80 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| La Puebla de Valverde | Sarrión-Mijares | MN17 | 2.13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Huélago | Guadix-Baza | MN16 | 2.60 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Huéscar 3 | Guadix-Baza | MN15 | 3.70 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Layna | Tajo | MN15 | 3.91 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| La Gloria 4 | Teruel | MN14 | 4.19 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Venta del Moro | Cabriel | MN13 | 5.69 | 3 | 8 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Milagros | Teruel | MN13 | 5.69 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Las Casiones | Teruel | MN13 | 6.08 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| El Arquillo 1 | Teruel | MN13 | 6.32 | 1 | 3 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cerro de la Garita | Teruel | MN12 | 7.01 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Los Mansuetos | Teruel | MN12 | 7.01 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Puente Minero | Teruel | MN11 | 7.83 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Masía de la Roma 604B | Teruel | MN10 | 8.26 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| La Roma 2 | Teruel | MN10 | 8.79 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Los Valles de Fuentidueña | Duero | MN9 | 9.55 | 15 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nombrevilla 1 | Calatayud-Daroca | MN9 | 10.87 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cerro del Otero | Duero | MN7/8 | 11.13 | 3 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Numbers indicate the presence and number of specimens analyzed in each locality. MP is middle Pleistocene. Age from Domingo et al. ([16], unpublished data).

The stable carbon and oxygen isotope composition of tooth enamel was analyzed for proboscideans, suids, giraffids, cervids, bovids, and equids from 18 localities from the Iberian Peninsula spanning from 11.1 to 0.8 Ma (late Miocene-middle Pleistocene) (Table S1). Chronological ages of the studied localities are from Domingo et al. ([16] and unpublished data). Although ages are assigned for each fossil site, the MN (Mammal Neogene) biochronology is used in order to allow comparisons among localities [17]–[21]. Since all the basins studied here belong to the same biogeographic province [22], the use of the MN units to aggregate fossil sites is assumed to be an appropiate approach, despite the fact that the Mammal Neogene biochronological system has been challenged as a true biozonation at larger scales [22]–[24].

Tooth enamel was sampled using a rotary drill with a diamond-tipped dental burr. Fossil teeth for this study are housed in the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC (Madrid, Spain) and Fundación Conjunto Paleontológico de Teruel-Dinópolis (Teruel, Spain), after being recovered in excavations carried out with public funding. Sampling was performed with the permission of both institutions.

Measurement of δ13C values of fossil tooth enamel allows for characterization of the diet of extinct taxa, providing a means to reconstruct past landscapes and habitats [25]–[31]. For herbivorous mammals, the δ13C value of tooth enamel (δ13Cenamel) has a direct relationship to the δ13C value of the diet (δ13Cdiet), which varies depending on plant photosynthetic pathways (C3, C4, CAM), as well as ecological factors (aridity, canopy density, etc.) that affect fractionation during photosynthesis [32]–[33]. The δ18O values in the carbonate and phosphate fractions of mammalian tooth enamel record the δ18O value of body water (δ18Obw), which in turn is a reflection of oxygen uptake (inspired O2 and water vapor, drinking water, dietary water, oxygen in food dry matter) and loss (excreted water and solids, expired CO2, and water vapor) during tooth development [34]–[35]. Carbon and oxygen isotope results are reported in δ-notation δHXsample = [(Rsample–Rstandard)/Rstandard]×1000, where X is the element, H is the mass of the rare, heavy isotope, and R = 13C/12C or 18O/16O. Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) is the standard for δ13C values, and δ18O values are reported relative to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW).

Tooth enamel samples (n = 149) were analyzed for the carbon and oxygen isotope composition of carbonate in bioapatite (δ13C and δ18OCO3, respectively). Carbonate analyses were conducted at the stable isotope laboratories of the University of California Santa Cruz using a ThermoScientific MAT253 dual inlet isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled to a ThermoScientific Kiel IV carbonate device and of the University of Minnesota using a ThermoScientific MAT252 dual inlet isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled to a ThermoScientific Kiel II carbonate device. Approximately 5–6 mg of tooth enamel were sampled and treated with 30% H2O2 for 24 h. Samples were rinsed 5 times in deionized (DI) water and soaked for 24 h in 1 M acetic acid buffered to ∼pH 5 using Ca acetate solution. After 5 rinses with DI water, the resulting solid was freeze-dried at −40°C and at a pressure of 25×10−3 Mbar for 24 h. The standards used were Elephant Enamel Standard (EES, δ13C = −7.8‰ and δ18O = 1.6‰), Carrara Marble (CM, δ13C = 1.97‰ and δ18O = −1.61‰), NBS−18 (δ13C = −5.03‰ and δ18O = −23.01‰) and NBS-19 (δ13C = 1.95‰ and δ18O = −2.20‰). The standard deviations for repeated measurements of EES (n = 5), CM (n = 18), NBS-18 (n = 11) and NBS-19 (n = 6) were 0.06‰, 0.03‰, 0.04‰ and 0.08‰ for δ13C, respectively, and 0.19‰, 0.10‰, 0.05‰ and 0.08‰ for δ18O, respectively. Duplicate analyses were carried out for ∼10% of the samples (n = 15). The average absolute differences for δ13C and δ18OCO3 values were 0.04‰ and 0.38‰, respectively, and the standard deviations of these average differences were 0.15‰ and 0.29‰ for δ13C and δ18OCO3 values, respectively.

The δ18O values of phosphate in bioapatite (δ18OPO4) were measured on 149 enamel samples. Analyses were performed at the stable isotope laboratories of the University of California Santa Cruz using a ThermoFinnigan Delta plus XP IRMS coupled to a ThermoFinnigan High Temperature Conversion Elemental Analyzer (TCEA) and of the University of Kansas using a Thermo Finnigan MAT 253 IRMS coupled to a ThermoFinnigan TCEA. The chemical treatment is described in ÓNeil et al. [36] and Bassett et al. [37]. Between 1.5 and 2 mg of tooth enamel were recovered and dissolved in 100 µl of 0.5 M HNO3. 75 µl of 0.5 M KOH and 200 µl of 0.36 M KF were added to neutralize the solution and to precipitate CaF2 and other fluorides, respectively. Samples were then centrifuged and after removing the resulting solid, 250 µl of silver amine solution (0.2 M AgNO3, 0.35 M NH4NO3, 0.74 M NH4OH) was added and the samples were maintained at 50°C overnight to precipitate Ag3PO4. The resulting Ag3PO4 crystals were recovered by centrifugation and rinsing with DI water (5 times), after which vials were placed in an oven overnight at 50°C. The standards used were Fisher standard (δ18O = 8.4‰), Ellen Gray-UCSC High standard (δ18O = 19.0‰), Kodak standard (δ18O = 18.1‰) and NIST 120c (δ18O = 21.8‰). The standard deviations for repeated measurements of Fisher Standard (n = 48), Ellen Gray-UCSC High standard (n = 16), Kodak standard (n = 11) and NIST 120c (n = 15) were 0.5‰, 0.4‰, 0.7‰ and 0.4‰, respectively. Duplicate δ18OPO4 analyses were carried out on ∼ 30% of the samples. The average absolute difference for δ18OPO4 was 0.09‰ and the standard deviation of this average difference was 0.23‰.

To construct δ13C, δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 temporal trends, we have grouped our localities by MN and we calculated the weighted mean of isotopic values according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where XMN is the mean isotopic value (δ13C, δ18OCO3, δ18OPO4) for each MN, xa and xb are mean isotopic values for taxa a and b, and na and nb are the number of selected teeth for taxa a and b. We opted to use the weighted mean since the number of analyzed teeth differs among taxa and therefore, they do not contribute equally to the final average. The application of the weighted mean when constructing temporal trends allows to avoid biases due to differences in physiological and ecological traits among taxa.

MAP was estimated following the work of Kohn [38] after a modern equivalent of diet composition (δ13Cdiet, meq) had been calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where δ13Cleaf = δ13Ctooth –14.1‰ [39], δ13Cmodern atmCO2 is −8‰, and δ13Cancient atmCO2 is the mean δ13CatmCO2 values from Tipple et al. [40] considering the following time bins: late Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene (Table S2).

The δ18O value of the water (δ18Ow) ingested by fossil mammals was calculated using fossil mammal tooth enamel δ18OPO4 values and equations established for modern mammals (Table S3). Equations were selected according to the closest living relative of the fossil taxa assuming there were no significant differences in the δ18OPO4-δ18Ow fractionation between modern and fossil mammals.

Finally, we used a regression equation between MAT and weighted δ18Ow estimated using meteorological data included in Rozanski et al. [41]:

| (3) |

Equation 3 was selected because it uses data from meteorological stations worldwide, hence all existing climate regimes are represented. Tectonic reorganization including the closure and opening of sea gateways (e.g., closure of the Panama Isthmus and the passage between the Indian Ocean and the Tethys, opening of the Drake passage and Bering Strait), the uplift of mountain chains (e.g., Himalaya, Andes, Alps) along with shifts in the orbital cycles have exerted an important control on global ice volume and distribution as have perturbations in the atmospheric CO2 concentration and, by extension, in the carbon cycle. These factors have given rise to different climate regimes since the late Miocene and have culminated in modern climate configuration. In general, Cenozoic climates were globally warmer than at present as corroborated by different proxies [1], [42]–[44]. Warmer conditions have also been recorded in Western Europe during the Miocene and most of the Pliocene based on palynology, vertebrate fossils and General Circulation Models [11], [42], [45]–[46] with the definitive establishment of the Mediterranean climate regime at some point between 3.4 and 2.5 Ma [10]–[11]. Hernández Fernández et al. [10] and van Dam [12] highlighted the migration of the atmospheric cells, with the subtropical high pressure belt (between the Ferrel and Hadley cells) fluctuating since the late Miocene and profoundly affecting the distribution of Iberian ecosystems. Biome analyses carried out in the Iberian Peninsula between the Miocene and Pleistocene based on macro- and micro-mammals assemblages [10], [47]–[48] detected a shift in biomes from tropical deciduous woodland, savanna and subtropical desert during the Miocene and Early Pliocene, to nemoral broadleaf deciduous forest for the Late Pliocene, to the modern Mediterranean conditions characterized by schlerophyllous woodland-shrubland since the end of the Pliocene. Due to the different climate regimes and biomes that existed in the Iberian Peninsula during the period under study (late Miocene-middle Pleistocene), it is necessary to use a MAT-δ18Ow relationship that considers data from a wide range of climate regimes and biomes.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS PASW Statistics 18.0 software. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare linear regressions. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student-t tests were used to detect significant differences in isotopic data among taxa within MN intervals, whereas ANOVA and post-hoc Tukeýs analyses were used to analyze the variability of the isotopic record among MNs.

Results and Discussion

Diagenesis

The potential for diagenetic alteration should be assessed before accepting paleoecological or paleoenvironmental interpretations based on stable isotope results from fossil bioapatite. Here, only tooth enamel was analyzed, as it is the mineralized tissue least likely to experience isotopic alteration during diagenesis [49]. Phosphate oxygen is more resistant to inorganic isotopic exchange than carbonate oxygen, but carbonate oxygen is more resistant to microbially-mediated exchange [50].

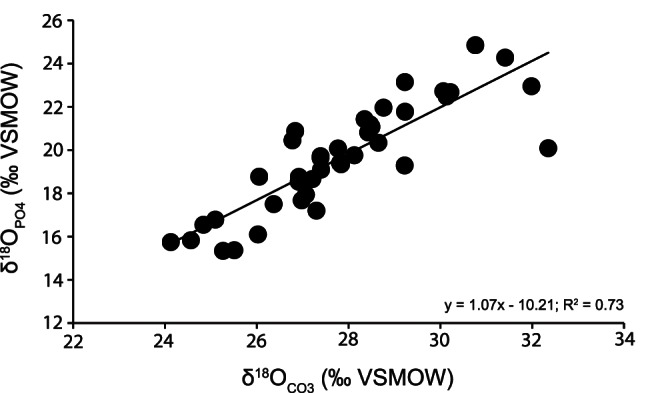

Modern, unaltered bioapatites exhibit a linear relationship between δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 with a consistent difference (δ18OCO3 - δ18OPO4 = ?18OCO3-PO4) of 8.6–9.1‰ for co-occurring CO3 −2 and PO4 −3 formed in isotopic equilibrium with body water at a constant temperature [51]–[53]. In this study, the mean ?18OCO3-PO4 was 8.2±1.3‰ (VSMOW), close to the expected value. Figure 2 shows the δ18OPO4-δ18OCO3 regression from this study. Zazzo et al. [50] suggested that the slope of the regression line between δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 is close to 1 in modern (unaltered) bioapatite. Slopes higher than unity suggest more extensive alteration of δ18OCO3 by inorganic mechanisms, whereas slopes lower than unity indicate a higher degree of microbially-mediated isotopic exchange of phosphate. Our slope is close to unity, but slightly higher (1.07). This slope is not as high as those observed by Zazzo et al. [50] in samples affected by intense diagenesis (see their Fig. 4) and no significant differences were detected by an ANCOVA test between our δ18OPO4-δ18OCO3 regression line and those proposed by Bryant et al. [52] and Iacumin et al. [53] (F = 0.473, p = 0.874).

Figure 2. Regression line for mean δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 (‰ VSMOW) values.

Each point represents mean isotopic value for each taxon per locality.

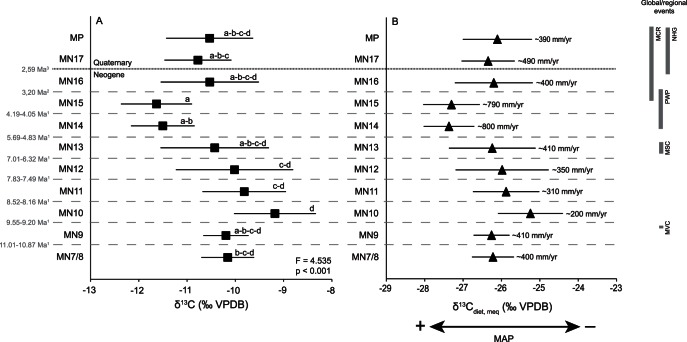

Figure 4. δ13C and δ13Cdiet, meq (‰ VPDB) values across time bins.

A) Mean and standard deviation δ13C (‰ VPDB) values in each MN. Letters indicate Tukeýs homogeneous groups. B) Mean and standard deviation δ13Cdiet, meq (‰ VPDB) in each MN with mean annual precipitation (after Kohn [38]). Chronology according to 1Domingo et al. ([16], unpublished data), 2Agustí et al. [89], 3the onset of the Quaternary according to the chronology confirmed in 2009 by the International Union of Geological Sciences. The ages of the global/regional events are not absolute, but approximate according to the MN chronology. MCR = Mediterranean Climate Regime, NHG = Northern Hemisphere glaciation, PWP = Pliocene Warm Period, MSC = Messinian Salinity Crisis, MVC = Middle Vallesian Crisis.

These results suggest that our samples have experienced minimal isotopic alteration of either phosphate or carbonate oxygen. There are no comparable tests for carbon isotopes, but the fact that species cluster in bivariate isotope space, and that the relative positions of these clusters are consistent for some taxa, suggest that animal paleobiology, and not diagenesis, is the main driver of isotopic variation.

Paleoecology of the Iberian Fossil Mammalian Taxa

In terrestrial settings, the dominant control on the δ13C value of plants is photosynthetic pathway [54]–[58]. Plants following the C3 or Calvin-Benson photosynthetic pathway (trees, shrubs, forbs and cool-season grasses) strongly discriminate against 13C during fixation of CO2, yielding tissues with δ13C values averaging −27‰ (VPDB) (ranging from −36 and −22‰). The most negative δ13C values of this range (−36 to −30‰) reflect closed-canopy conditions due to recycling of 13C-depleted CO2 and low irradiance. The highest values (−25 to −22‰) correspond to C3 plants from high light, arid, or water stressed environments. C4 plants (Hatch-Slack photosynthetic pathway) comprise grasses and sedges from areas with a warm growing season and some arid-adapted dicots. C4 plants discriminate less against 13C during carbon fixation, yielding mean δ13C value of −13‰ (ranging from −17‰ to −9‰). Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) is the least common pathway, occurring chiefly in succulent plants. CAM plants exhibit δ13C values that range between the values for C3 and C4 plants. Using the expected δ13C ranges for C3 and C4 plants and a typical diet-to-enamel fractionation of +14.1±0.5‰ [39], we can estimate the expected δ13C values for pure C3 feeders in different habitats (closed-canopy, −22 to −16‰; woodland-mesic C3 grassland, −16 to −11‰; open woodland-xeric C3 grassland, −11 to −8‰) and pure C4 feeders (−3‰ to +5‰). Enamel δ13C values between −8‰ and −3‰ represent mixed C3–C4 diets. When considering fossil taxa, however, it is necessary to account for shifts in the δ13C value of atmospheric CO2 (the source of plant carbon), including anthropogenic modification due to fossil fuel burning, which has decreased the δ13C value of atmospheric CO2 from −6.5 to −8‰ since onset of the Industrial Revolution [59]–[60]. Using isotopic data from marine foraminifera, Tipple et al. [40] reconstructed the δ13C value of the atmospheric CO2 since the Cretaceous. In order to calculate vegetation δ13C end-members, we considered the following time bins: late Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene. Table 2 shows a summary with δ13CatmCO2 and δ13C cut-off values for the transition between diets composed of different types of vegetation for the late Miocene, the Pliocene and the Pleistocene. The absolute cut-off δ13C value between woodland-mesic C3 grassland and open woodland-xeric C3 grassland is difficult to determine, but our threshold values are in agreement with previous studies. In this sense, Kohn et al. [61] suggested a threshold value of −9‰ between woodland and more open conditions when investigating a North American Pleistocene fossil site. Our C3 range also agrees well with Feranec et al. [62] who proposed a range of pure C3 δ13C values between −19.5‰ and −6.5‰, in a study focused on a Spanish Pleistocene fossil site. Matson et al. [63] compiled plant δ13C values from different types of modern ecosystems and our cut-off δ13C values for open woodland-xeric C3 grassland fit well with δ13C values for C3 trees, shrubs and grasses found mainly in Mediterranean forest, woodland and scrub, tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forest, and desert and xeric shrubland, therefore pointing to some degree of aridity for that range of δ13C values. Figure 3 presents biplot δ18OCO3- δ13C graphs for each MN. Table 3 shows mean isotopic values for each taxon and their inferred dietary behaviour according to previous studies based on tooth morphology, microwear and isotopes. The whole isotopic dataset and statistical analyses are shown in Tables S1 and S4, respectively.

Table 2. δ13C of atmospheric CO2 (δ13CatmCO2) and mammalian enamel δ13C (δ13Cenamel) cut-off values between different environments in the late Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene.

| Late Miocene | Pliocene | Pleistocene | |

| δ13CatmCO2 | −6.2 | −6.3 | −6.5 |

| δ13Cenamel closed canopy forest | < −14.2 | < −14.3 | < −14.5 |

| δ13Cenamel woodland to woodland-mesic C3 grassland | −14.2 to −9.2 | −14.3 to −9.3 | −14.5 to −9.5 |

| δ13Cenamel open woodland-xeric C3 grassland | −9.2 to −6.2 | −9.3 to −6.3 | −9.5 to −6.5 |

| δ13Cenamel mixed C3–C4 grassland | −6.2 to −1.2 | −6.3 to −1.3 | −6.5 to −1.5 |

| δ13Cenamel C4 grassland | > −1.2 | > −1.3 | > −1.5 |

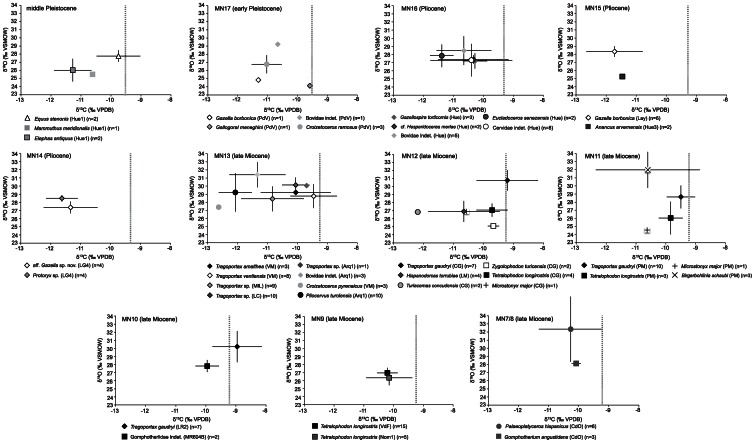

Figure 3. δ18OCO3 (‰ VSMOW) versus δ13C (‰ VPDB) for mammalian taxa in each MN and middle Pleistocene.

Mean and standard deviation values are provided. Dashed grey line indicates the cut-off δ13C value between woodland-mesic C3 grassland and open woodland-xeric C3 grassland. CdO = Cerro del Otero, Nom1 = Nombrevilla 1, VdF = Los Valles de Fuentidueña, LR2 = La Roma 2, MR604B = Masía de la Roma 604B, PM = Puente Minero, LM = Los Mansuetos, CG = Cerro de la Garita, Arq1 = El Arquillo 1, LC = Las Casiones, MIL = Milagros, VM = Venta del Moro, LG4 = La Gloria 4, Lay = Layna, Hue3 = Huéscar 3, Hue = Huélago, PdV = La Puebla de Valverde, Hue1 = Huéscar 1. n is the number of sampled teeth.

Table 3. Site, MN, age (Ma), family, taxa, mean ±1 SD δ13C (‰ VPDB), δ18OCO3 (‰ VSMOW) and δ18O PO4 (‰ VSMOW) values, inferred diet and references to other studies.

| Site | MN | Age (Ma) | Family | Taxa | δ13CCO3 (‰ VPDB) | δ18OCO3 (‰ VSMOW) | δ18OPO4 (‰ VSMOW) | Diet | References |

| Huéscar 1 | MP | 0.80 | Elephantidae | Mammuthus meridionalis | −10.6 | 25.5 | 15.4 | Mixed feeder-Grazer | [64], [78]–[80] |

| Huéscar 1 | MP | 0.80 | Elephantidae | Elephas antiquus | −11.3±0.6 | 26.0±1.4 | 16.1±1.4 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [76], [77] |

| Huéscar 1 | MP | 0.80 | Equidae | Equus stenonis | −9.8±0.7 | 27.8±0.7 | 20.1±0.1 | Grazer | [70] |

| La Puebla de Valverde | MN17 | 2.13 | Bovidae | Gazella borbonica | −11.3 | 24.8 | 16.5 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [67]–[68], [70], [73]–[74] |

| La Puebla de Valverde | MN17 | 2.13 | Bovidae | Gallogoral meneghini | −9.6 | 24.1 | 15.7 | Mixed feeder | [82] |

| La Puebla de Valverde | MN17 | 2.13 | Bovidae | Undetermined Bovidae | −10.7 | 29.2 | 21.8 | ||

| La Puebla de Valverde | MN17 | 2.13 | Cervidae | Croizetoceros ramosus | −11.0±0.5 | 26.8±1.1 | 20.5 | Browser | [64], [70] |

| Huélago | MN16 | 2.60 | Bovidae | Gazellospira torticornis | −10.3±0.4 | 27.2±1.0 | 18.7±1.4 | Mixed feeder | [70] |

| Huélago | MN16 | 2.60 | Bovidae | cf. Hesperidoceras merlae | −10.3±1.2 | 27.4±0.5 | 19.7±0.5 | Mixed feeder | J. Morales, pers. comm. |

| Huélago | MN16 | 2.60 | Bovidae | Undetermined Bovidae | −10.7±0.9 | 28.5±1.8 | 21.2±3.0 | ||

| Huélago | MN16 | 2.60 | Cervidae | Undetermined Cervidae | −10.4±1.4 | 27.3±2.0 | 17.2±2.1 | ||

| Huélago | MN16 | 2.60 | Cervidae | Eucladoceros senezensis | −11.4±0.4 | 27.8±1.4 | 19.4±2.4 | Oportunistic feeder | [75] |

| Huéscar 3 | MN15 | 3.70 | Gomphoteriidae | Anancus arvernensis | −11.5±0.02 | 25.3±0.1 | 15.3±0.3 | Browser | [64], [72] |

| Layna | MN15 | 3.91 | Bovidae | Gazella borbonica | −11.7±0.9 | 28.4±0.7 | 21.4±1.8 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [67]–[68], [70], [73]–[74] |

| La Gloria 4 | MN14 | 4.19 | Bovidae | aff. Gazella sp. nov. | −11.3±0.9 | 27.4±0.7 | 19.6±2.5 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [67]–[68], [70], [73]–[74] |

| La Gloria 4 | MN14 | 4.19 | Bovidae | Protoryx sp. | −11.6±0.5 | 28.5±0.4 | 21.1±0.7 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [67], [74] |

| Venta del Moro | MN13 | 5.69 | Bovidae | Tragoportax amalthea | −10.1±1.2 | 29.2±0.3 | 23.2±0.9 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| Venta del Moro | MN13 | 5.69 | Bovidae | Tragoportax ventiensis | −9.5±0.8 | 28.8±1.5 | 22.0±1.8 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| Venta del Moro | MN13 | 5.69 | Cervidae | Croizetoceros pyrenaicus | −12.6 | 27.4 | 19.1±0.8 | Browser | [64], [70] |

| Milagros | MN13 | 5.69 | Bovidae | Tragoportax sp. | −10.8±1.1 | 28.4±1.5 | 20.8±2.1 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| Las Casiones | MN13 | 6.08 | Bovidae | Tragoportax sp. | −10.1±0.5 | 30.1±0.9 | 22.5±0.9 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| El Arquillo 1 | MN13 | 6.32 | Bovidae | Tragoportax sp. | −9.7 | 30.1 | 22.7 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| El Arquillo 1 | MN13 | 6.32 | Bovidae | Undetermined Bovidae | −11.3±0.9 | 31.4±1.6 | 24.3±1.5 | ||

| El Arquillo 1 | MN13 | 6.32 | Cervidae | Pliocervus turolensis | −12.1±0.6 | 29.2±2.4 | 19.3±1.2 | Browser | [64] |

| Cerro de la Garita | MN12 | 7.01 | Bovidae | Tragoportax gaudryi | −9.2±1.0 | 30.8±1.3 | 24.9±0.6 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| Cerro de la Garita | MN12 | 7.01 | Mammutidae | Zygolophodon turicensis | −9.7±0.2 | 25.1±0.1 | 16.8±0.7 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [64] |

| Cerro de la Garita | MN12 | 7.01 | Gomphoteriidae | Tetralophodon longirostris | −9.7±0.5 | 27.1±0.8 | 17.9±0.4 | Browser | [64] |

| Cerro de la Garita | MN12 | 7.01 | Suidae | Microstonyx major | −10.6 | 26.9 | 18.8 | Omnivore | [64] |

| Cerro de la Garita | MN12 | 7.01 | Cervidae | Turiacemas concudensis | −12.2±0.1 | 26.8±0.2 | 20.9±0.9 | Browser | J. Morales, pers. comm. |

| Los Mansuetos | MN12 | 7.01 | Bovidae | Hispanodorcas torrubiae | −10.7±1.2 | 26.9±1.3 | 18.5±1.3 | Browser-Mixed feeder | [68] |

| Puente Minero | MN11 | 7.83 | Bovidae | Tragoportax gaudryi | −9.5±0.5 | 28.7±1.4 | 20.3±2.2 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| Puente Minero | MN11 | 7.83 | Gomphoteriidae | Tetralophodon longirostris | −9.8±0.4 | 26.1±2.0 | 18.8±1.3 | Browser | [64] |

| Puente Minero | MN11 | 7.83 | Suidae | Microstonyx major | −10.6 | 24.6 | 15.8 | Omnivore | [64] |

| Puente Minero | MN11 | 7.83 | Giraffidae | Birgerbohlinia schaubi | −10.6±1.7 | 32.0±2.2 | 23.0±1.8 | Browser | J. Morales, pers. comm. |

| Masía de la Roma 604B | MN10 | 8.26 | Gomphoteriidae | Undetermined Gomphotheriidae | −10.0±0.4 | 27.8±0.7 | 19.4±0.0 | Browser | |

| La Roma 2 | MN10 | 8.79 | Bovidae | Tragoportax gaudryi | −9.0±0.8 | 30.2±1.9 | 22.7±2.4 | Mixed feeder with strong grazing habits | [66], [67] |

| Los Valles de Fuentidueña | MN9 | 9.55 | Gomphoteriidae | Tetralophodon longirostris | −10.2±0.3 | 27.0±0.6 | 17.7±0.7 | Browser | [64] |

| Nombrevilla 1 | MN9 | 10.87 | Gomphoteriidae | Tetralophodon longirostris | −10.2±0.8 | 26.4±0.9 | 17.5±1.5 | Browser | [64] |

| Cerro del Otero | MN7/8 | 11.13 | Gomphoteriidae | Gomphotherium angustidens | −10.1±0.2 | 28.1±0.3 | 19.8±0.3 | Browser | [64] |

| Cerro del Otero | MN7/8 | 11.13 | Cervidae | Palaeoplatyceros hispanicus | −10.3±1.1 | 32.4±4.0 | 20.1±2.2 | Browser | [64] |

MP is middle Pleistocene. Age from Domingo et al. ([16], unpublished data).

Late Miocene (Cerro del Otero, MN7/8–Venta del Moro, MN13)

Among Miocene proboscideans, Gomphotherium angustidens had brachyo-bunodont dentition, suggesting a browsing behaviour, which is in agreement with δ13C values pointing to consumption of woodland or woodland/C3 grassland vegetation. The gomphothere Tetralophodon longirostris replaced Gomphotherium angustidens. Tetralophodon was larger and more hypsodont than Gomphotherium, but also probably a browser [64]. Its δ13C values shift from lower values similar to Gomphotherium in older localities (Nombrevilla and Los Valles de Fuentidueña, MN9) to ∼0.5‰ higher values in younger sites (Puente Minero, MN11 and Cerro de la Garita, MN12). The mammutid Zygolophodon turicensis from the Cerro de la Garita locality had a zygodont dentition with sharp, transverse ridges and δ13C values similar to those for the youngest Tetralophodon. Overall, the slight trend of increasing δ13C values toward the end of the Miocene in these proboscideans points to consumption of plants from increasingly open, drier habitats. Since proboscideans are obligate drinkers [34], [65], the difference in δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values likely reflects a change in the isotopic composition of ingested δ18Ow spatially or temporally. In this case, Z. turicensis has the lowest isotopic values, with intermediate values for T. longirostris and the highest values for G. angustidens. This might be indicating differences in the source of ingested water with G. angustidens drinking in more open settings (Fig. 3, Table 3).

In the case of Miocene bovids, the boselaphine Tragoportax is the best-represented genus. It had relatively long limbs suggesting cursorial adaptations and preference for open habitats [64]. Microwear studies performed on the teeth of this bovid suggest it was a mixed feeder with strong grazing habits [66]–[67]. This is consistent with its δ13C values, which are the highest for any taxon in all the MNs in which Tragoportax occurs (Fig. 3), and in most MNs are close to values expected for animals foraging in open woodlands or dry C3 grasslands. In the MN13 fossil sites, Tragoportax δ13C values were ∼1–2‰ lower, most likely due to a shift towards more humid conditions (see next section and Fig. 4). Using dental microwear, Merceron et al. [68] showed that a species of the bovid Hispanodorcas from the Neogene of northern Greece (H. orientalis) had strong similarities to extant browsers and mixed feeders; that reconstruction is also consistent with the δ13C values of H. torrubiae from Los Mansuetos (MN12; Fig. 3). According to Merceron et al. [69], Tragoportax was likely an obligate drinker based on a low inter-individual δ18O variability among species, and therefore its high δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values when compared to the rest of taxa (including the bovid H. torrubiae) in MN10–12 (Fig. 3, Table 3) are consistent with ingestion of evaporated water in open environments.

Cervids have the lowest δ13C values of the late Miocene mammalian assemblage (Fig. 3), consistent with membership in the browsing guild as indicated by tooth morphology and microwear analyses [64], [70] (Table 3). The very low values for the cervids in MN12 and MN13 (between −12 and −13‰) point to foraging in a denser woodland, but not a closed canopy forest. Cervid δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values yield different results with intermediate δ18OCO3 values (relative to other mammals), but consistently low δ18OPO4 values (Table 3). Cervids likely drank in the closed environments in which they foraged (which would yield low δ18O values). Therefore, the intermediate δ18OCO3 values point to some degree of alteration.

Like modern giraffes, although with a shorter neck, the giraffid Birgerbohlinia schaubi was likely a browser; this interpretation is supported by δ13C values indicative of woodland foraging. The very high δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values in B. schaubi relative to other mammals from the Puente Minero (MN11) locality (and most other late Miocene mammals) (Fig. 3, Table 3) may indicate that this sivatherine obtained much of its water from highly evaporated leave water as suggested by Cerling et al. [71] for the extinct Palaeotragus and Levin et al. [65] for modern giraffids.

Finally, the suid Microstonyx major has intermediate δ13C values in the Puente Minero (MN11) and Cerro de la Garita (MN12) fossil sites. Suids are more omnivorous and according to Agustí and Antón [64], M. major had a cranial morphology suggesting a strong and highly mobile muzzle disk (like in modern pigs) interpreted as an adaptation to digging roots and tubers, although other sources of dietary intake such as fruits, insects and even carrion cannot be discarded, the combination of which may have given rise to the observed intermediate δ13C values.

Pliocene (La Gloria 4, MN14–Huélago, MN16)

The gomphothere Anancus arvernensis has δ13C values indicative of browsing in a woodland to woodland-mesic C3 grassland (Fig. 3), which is consistent with observations by Agustí and Antón [64] and Tassy [72] who argued that its dentition was similar to that of other tetralophodont gomphotheres. Low δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values may relate to ingestion of water in closed areas or flowing water not subject to significant evaporation (Fig. 3, Table 3).

The Pliocene bovids Gazella and Protoryx were ubiquitous taxa as far as occupancy of different habitats is concerned and are considered browsers to mixed feeders [67]–[68], [70], [73]–[74]; the relatively low δ13C values for these taxa are more supportive of a browsing habitat (Fig. 3, Table 3). Rivals and Athanassiou [70] argued that the antelope Gazellospira torticornis was a mixed feeder that grazed on seasonal or regional basis. Although this antelope has ∼1 to 1.5‰ higher δ13C values than Gazella and Protoryx, these values are consistent with woodland browsing and do not point to a substantial proportion of grass in the diet. The bovid cf. Hesperidoceras merlae has similar δ13C values to G. torticornis (Fig. 3, Table 3), supporting also woodland browsing. Pliocene bovid δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values show a slight decrease towards younger sites related to a change in global conditions in the Pliocene (Table 3), but δ18O values agree well with the ingestion of non-evaporated waters.

The cervid Eucladoceros senezensis has the lowest δ13C value of the mammalian assemblage from the Huélago locality (MN16), although that value is still typical of a woodland and not of a closed canopy forest. Eucladoceros was a large-sized deer and, according to Croitor [75], it had an oportunistic feeding behaviour that allowed it to occupy more open environments as well as the more closed habitats typically used by cervids. Pliocene cervids from Huélago have similar δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values to bovids, indicating a similar source of ingested water.

Pleistocene (La Puebla de Valverde, MN17–Huéscar 1)

Filippi et al. [76] and Palombo et al. [77] studied microwear on Elephas antiquus of the Middle Pleistocene and suggested a browsing to mixed feeding behaviour; our δ13C data are consistent with woodland browsing but do not point to a substantial proportion of grass in the diet (Fig. 3). Mammuthus meridionalis has been considered to be a mixed feeder to grazer based on microwear and previous stable isotope analyses [78]–[80]. Our M. meridionalis δ13C value is more indicative of a mixed feeder occupying a woodland (Fig. 3).

The bovid, Gallogoral meneghini from La Puebla de Valverde (MN17) has higher δ13C values, close to those expected for an animal foraging in an open woodland (Fig. 3, Table 3). According to Guérin [81], Agustí and Antón [64] and Brugal and Croitor [82], G. meneghini was a mixed feeder with a robust skeleton and short limbs adapted to locomotion on mountainous uneven areas similar to modern gorals from Asia. Fakhar-i-Abbas et al. [83] studied the feeding preferences of the gray goral and found out that it relies mainly on grasses, although it can browse too; this is in agreement with our G. meneghini δ13C values situated towards the high cut-off for open woodland and mesic C3 grassland. Lower δ13C values in the case of Gazella borbonica are similar to those for this bovid in the Pliocene and again these values are consistent with woodland browsing and do not point to a substantial proportion of grass in the diet.

The cervid Croizetoceros ramosus also shows low δ13C values indicative of a woodland. The equid Equus stenonis has higher δ13C values near those expected for animals feeding in an open woodland (Fig. 3). This might be indicating ingestion of C3 grasses not subject to water stress. Slightly higher δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values for the equid E. stenonis and the cervid C. ramosus in comparison to the elephantids and bovids may suggest ingestion of water in more open areas (in the case of the equid) or consumption of more evaporated water in leaves (in the case of the cervid) (Fig. 3, Table 3).

Changes in δ13C Values

Figure 4 shows δ13C and modern equivalent δ13C values (δ13Cdiet, meq), which can be related to MAP (see material and methods section and Table S2) between MN7/8 and the middle Pleistocene.

A prominent faunal turnover event, known as the Middle Vallesian Crisis (ca. 9.6 Ma) [84] occurred in Western Europe between MN9 and MN10. This event is recognized by the replacement of humid-adapted taxa with taxa more adapted to drier conditions, and is associated with the replacement of evergreen subtropical woodlands by a seasonally adapted deciduous woodland as observed by Agustí and Moyà-Solà [85] and Agustí et al. [84] in the Vallès-Penedès Basin (North Eastern Iberian Peninsula). This event coincides with the Mi7 positive shift in benthic foraminifera δ18O values interpreted to reflect global cooling [86]–[87]. In Figure 4A, δ13C values of herbivorous mammals in the Iberian Peninsula increase between MN9 (Nombrevilla 1 and Los Valles de Fuentidueña) and MN10 (La Roma 2 and Masía de la Roma 604B), which may be related to a change towards drier conditions. δ13Cdiet, meq values mirror tooth enamel δ13C values, with an increase observed between these MNs (Fig. 4B). MAP values (estimated after Kohn, [38]) dropped from ∼410 mm/yr to ∼200 mm/yr between MN9 and MN10. Böhme et al., [13]), who used the ecophysiological structure of herpetofaunas in the Calatayud-Daroca Basin of Spain to estimate changes in MAP over the Miocene, also recognized a decrease in precipitation at 9.7–9.6 Ma. However, the decrease in the study of Böhme et al. [13] is greater than 1000 mm/yr in comparison with the ∼200 mm/yr decrease estimated here. The explanation for this large difference is unclear, but we note that the Kohn [38] method has relatively large error.

During MN13, the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC) in the Mediterranean Basin resulted from a sharp decrease in the marine water circulation from the Atlantic and culminated in the formation of thick evaporite deposits [8]. The lack of significant differences in mammal tooth enamel δ13C values between MN12 and MN13 (t = −1.285, p = 0.204) suggests that the MSC did not cause substantial modifications to terrestrial ecosystems, although a post-hoc Tukeýs test places the MN13 in groups a, b, c, and d (versus groups c and d for MN12) pointing to more humid conditions. However, and since we cannot unequivocally determine the synchrony between the chronology assigned to the MN13 localities considered in this study and the MSC, we regard this conclusion as preliminary pending more accurate datings. Ongoing paleomagnetic analyses in the MN13 Venta del Moro fossil site may modify the current chronology, which places this locality as contemporaneous to the MSC (J. Morales, pers. comm. 2013). Fauquette et al. [88] carried out an analysis of 20 pollen sequences in the Mediterranean realm and found no differences when comparing data before, during and after the MSC.

Mean tooth enamel δ13C values decrease sharply from MN13 to MN14, and the mean value in MN15 is lower still (Fig. 4A). The statistically significant drop in δ13C values during MN14 and MN15 may be related to the Pliocene Warm Period which began at ∼5 Ma and brought about more humid conditions in Europe [1], [64]. Figure 4B also shows a drop in δ13Cdiet, meq, which corresponds to an increase in MAP values of ∼400 mm/yr between MN13 (∼ 410 mm/yr) and MN14 and MN15 (∼ 800 mm/yr). The decrease in δ13C values in MN14 and MN15 is not biased by the type of taxa sampled, since in La Gloria 4 and Layna ubiquitous taxa such as Gazella and Protoryx were chosen and therefore, an isotopic change in these generalistic bovids [67]–[68], [70], [73]–[74] points towards real paleoenvironmental variations.

After MN15, δ13C values increase in MN16, MN17 and middle Pleistocene, but do not reach values as high as those observed in MN10, MN11 and MN12 (Fig. 4A). This increase in δ13C values corresponds to global and regional climatic changes and to faunal and environmental changes in Europe. The beginning of MN16 (∼3.2 Ma) [89] predates the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation [1], [90]. At that time, the modern Mediterranean climatic regime was established and aridity in Europe was enhanced, which led to changes in mammalian fossil assemblages in such a way that, according to Agustí et al. [89], the Villanyian mammal turnover occurred at this time with an increase in grazers, the appearance of morphological features associated with a highly cursorial lifestyle in some ungulates, and the diversification of pursuit carnivores. All of these changes point towards the development of prairies and grasslands in Europe [64], [89]. Fortelius et al. [91] estimated hypsodonty index in mammalian herbivores between the Late Miocene and the Pliocene in Eurasia and found out that browsing taxa in MN15 were replaced by grazers in MN16 and MN17. Another important event occurred at ∼2.6 Ma, when there was a replacement of forests by tundra-like vegetation in northern and central Europe, while in northwestern Africa, savanna biome shrunk in favour of desert biome [64]. The Iberian Peninsula also experienced a shift towards the development of more herbaceous vegetation, such as the well-documented increase of Artemisia [11], [92]. The increase in mammal tooth enamel δ13C values observed in MN16, MN17 and the middle Pleistocene may reflect this episode.

Temperature Record

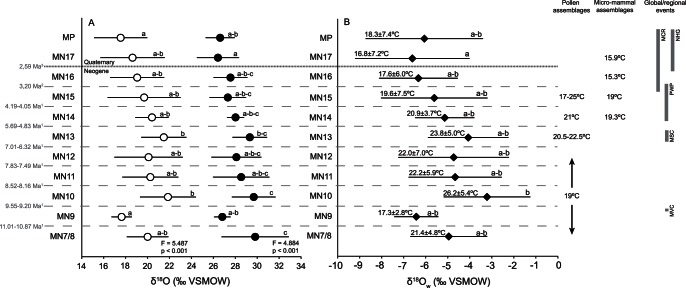

Figure 5 shows the variations in tooth enamel δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 values (Fig. 5A), and δ18Ow values and mean annual temperature (MAT) (Fig. 5B) estimated using the taxon-specific relationships (Table S3) and equation (3) from Rozanski et al. [41]. The Mi7 cooling event associated with the Middle Vallesian Crisis (between MN9 and MN10) is not evident in the tooth enamel δ18O values. Instead, δ18O values increase between MN9 and MN10, suggesting an increase in MAT (Fig. 5B). Based on pollen assemblages from the Iberian Peninsula, Jiménez-Moreno et al. [11] estimated that MAT during the Tortonian (MN7/8 to the middle of MN12) was 19°C. The mean MAT estimate from MN7/8 to MN12 in our study is slightly warmer, 21.8±3.2°C. Van Dam & Reichart [93] analyzed δ18OCO3 values on equid tooth enamel to estimate δ18Ow and MAT. They obtained a mean MAT of 15.4±2.1°C between MN9 and MN12, substantially lower than the values estimated here.

Figure 5. δ18OCO3 and δ18OPO4 (‰ VSMOW) values across time bins.

A) Mean and standard deviation δ18OCO3 (black circles) and δ18OPO4 (white circles) (‰ VSMOW) values. Letters indicate Tukeýs homogeneous groups. B) Mean and standard deviation δ18Ow (‰ VSMOW) and MAT (°C) values calculated by applying the equation (3) of Rozanski et al. [41]. MAT values based on pollen and micro-mammal data are from Fauquette et al. [88], [95], Hernández Fernández et al. [10] and Jiménez-Moreno et al. [11]. Chronology according to 1Domingo et al. ([16], unpublished data), 2Agustí et al. [89], 3the onset of the Quaternary according to the chronology confirmed in 2009 by the International Union of Geological Sciences. The ages of the global/regional events are not absolute, but approximate according to the MN chronology. MCR = Mediterranean Climate Regime, NHG = Northern Hemisphere glaciation, PWP = Pliocene Warm Period, MSC = Messinian Salinity Crisis, MVC = Middle Vallesian Crisis.

Jiménez-Moreno et al. [11] argued that during the Messinian, there were not major variations in climate before, during and after the MSC. The pollen assemblage from the Carmona section suggests a MAT between 20.5°C and 22.5°C during the Messinian in southwestern Spain. In our study, MN13 fossil sites that correspond to the Messinian suggest a warmer MAT of 23.8±5.0°C (Fig. 5B). Matson & Fox [94] estimated MAT using equid tooth enamel δ18OPO4 values and found an increase from 15.5°C for MN12 sites (Los Mansuetos and Concud) to 21.4°C for MN13 sites (Venta del Moro, Librilla, Molina de Segura and La Alberca). Van Dam & Reichart [93] obtained MAT values of 12.9°C for MN13, again much lower than other studies.

Fauquette et al. [88], [95] estimated MAT using pollen assemblages in the Mediterranean realm from the early Pliocene (∼MN14). Assemblages from the Andalucía G1 section indicate a MAT of 21°C. Tooth enamel δ18O values from MN14 localities in our study yield a comparable MAT of 20.9±3.7°C. Hernández Fernández et al. [10] used the bioclimatic analysis of Pliocene and Pleistocene rodent assemblages in the Iberian Peninsula and estimated a MAT of 19.3° during MN14, slightly lower than the estimates based on pollen assemblages and our data. The lowest MAT estimates for MN14 were from the isotopic studies by Matson & Fox [94] and van Dam & Reichart [93], who suggested MAT values of 16.1°C and 14.1°C, respectively.

Our estimate of MAT during MN15 is 19.6±7.5°C, in good agreement with that based on pollen from the Tarragona E2 section (17 to 25°C from 5.32 to 3 Ma) [11]. The estimates of Hernández Fernández et al. [10] based on rodent assemblages from MN15 (∼19°C) are also in good agreement.

After MN15, MAT values decrease, reflecting global cooling with the onset of the Northern Hemisphere glaciation at ∼2.7 Ma. Tooth enamel δ18O values from MN16 and MN17 in our study supplied MAT values of 17.6±6.0°C and 16.8±7.2°C respectively, slightly warmer than MAT values estimated by Hernández Fernández et al. [10] between MN16 (15.3°C) and MN17 (15.9°C). Once again, van Dam & Reichart [93] obtained the lowest MAT record for MN17 of 8.9°C. Nevertheless, the comparison of MAT values among studies that considered different fossil sites with ages younger than ∼2.7 Ma might be complicated by glacial-interglacial dynamics, which may have produced large shifts in temperature in relatively short periods of time.

Overall, the MAT values estimated here using mammalian tooth enamel are in good agreement with data from palynology and rodent assemblage analyses. Other isotopic studies on mammal tooth enamel from the Iberian Peninsula [93]–[94] showed consistently lower MAT values compared to those obtained here. This may be due to the use of different equations relating MAT and δ18Ow. We use the equation (3) of Rozanski et al. [41], whereas Matson & Fox [94] and van Dam & Reichart [93] applied MAT-δ18Ow equations from meteorological stations near the location of the fossil sites. As previously highlighted, during the span of time considered in this study (late Miocene-middle Pleistocene), climate regimes shifted, and the modern Mediterranean regime was established at some point between ∼3.4 and 2.5 Ma. Hence, a worldwide meteorological MAT-δ18Ow equation integrating data from a range of climate regimes may constitute a better basis for estimating MAT than equations integrating a narrower range of climate regimes derived from local meteorological MAT-δ18Ow data. However, the differences in reconstructed MAT based on δ18O values of mammalian bioapatite for the same intervals highlight the sensitiviy of these reconstructions to both sampling and the assumptions behind the reconstructions.

Absence of C4 Vegetation in Southwestern Europe

Our δ13C record offers no evidence of the high δ13C values typical of C4 consumers (Figs. 3 and 4, Table 2) and the calculation of the percentage of C4 vegetation points to a low C4 dietary intake (<20%) in most of the analyzed taxa. This percentage of C4 vegetation may reflect either an actual small fraction of C4 plants in mammal diets or it may be an artifact related to the ingestion of C3 plants from open areas subject to water stress (which therefore have higher δ13C values). The lack of a significant expansion of C4 plants in the Iberian Peninsula is intriguing. The expansion of C4 plants took place between 9 and 2 Ma in different regions [6]. C4 photosynthesis is favored under conditions of low atmospheric CO2, when growing seasons experience high temperature (i.e., summer rainfall), in arid regions, or in soils with high salinity. The combined effects of fires and herbivory may also lead to open environments where C4 grasses may thrive. Given the high temperatures suggested by our isotopic analyses (Fig. 5) and other proxy data, conditions in the late Miocene and early Pliocene would seem conducive to a regional C4 expansion if habitats were relatively open and there was adequate summer precipitation.

Palaeoclimatic studies of Iberian mammalian assemblages from late Miocene to middle Pleistocene (∼11.1 to 0.8 Ma) indicate that the most likely biomes at some of the fossil sites studied here (Puente Minero, Los Mansuetos, Cerro de La Garita, El Arquillo, Venta del Moro, La Gloria 4, Layna and Huéscar 1) were tropical deciduous woodland with perhaps occasional savanna and subtropical desert environments, prior to the development of the sclerophyllous woodland-shrubland at the start of the Pleistocene [10], [48]. By definition, a woodland supports woody cover of >40% and <80% with the remaining patches often dominated by grasses, either C3 or C4 [96]–[97]. In a study of the isotopic composition of individual pollen grains from ∼20 to 15 Ma in the Rubielos de Mora Basin, Urban et al. [98] showed that while the overall abundance of grass pollen was low and in the range expected for a woodland (10–15%), C4 grasses comprised 20–40% of the grains. Since there are no isotopic studies on pollen grains in the time interval selected for our study, we assume that C4 grasses were potentially present in the flora of the Iberian Peninsula since at least the Early Miocene.

While a detailed analysis of the ultimate cause/s for the low abundance of C4 plants in southwestern Europe after their expansion elsewhere is beyond the scope of this paper, there are several potential explanations. At middle latitudes, only regions with summer rainfall are suitable for C4 grasses. A seasonality of rainfall similar to the modern Mediterranean precipitation pattern, with precipitation occurring chiefly during the winter, would lead to very low abundance of C4 plants on the Iberian Peninsula. Several studies have questioned the age of 3.4 and 2.5 Ma for the onset of the Mediterranean climate and proposed that such a climate regime may have been present much earlier (e.g., [99]). For example, Axelrod [100] studied fossil leaves in the Mediterranean area and argued that sclerophyllous evergreen woodlands with chaparral undergrowth were present throughout the Miocene. Yet there is no way to determine if these species were dominant on the landscape, and Axelrod ([100]: p. 325) himself noted that sclerophyllous species might constitute part of the tropical-subtropical woodlands understory but that the “existence of chaparral and macchia over wide areas as climax vegetation in the Tertiary seems unlikely”.

Tzedakis [99] reviewed evidence for the onset of the Mediterranean climate regime and noted that seasonality similar to the summer-dry and winter-wet pattern may have appeared intermittently before the onset of the “true”-Mediterranean climate regime. The occasional occurrence of Mediteranean-like climate in the Iberian Peninsula in the early Pliocene has also been suggested by studies of rodent faunas and has been linked to the presence of bimodal precipitation regimes, which may produce a short summer dry season in addition to the winter dry season typical of tropical climates [10]. The prevalence of these short summer dry periods is probably not sufficient to explain the absence of C4-dominated landscapes.

An alternative is that C4 plants were somewhat more abundant, but that mammals selectively foraged on C3 plants, perhaps avoiding C4 plants because of their lower nutritional value [101]. Paleoecological studies from other regions suggest that this explanation is unlikely. In North America, South America, Asia and Africa (see a review in Strömberg [6]), when C4 plants became available (as determined by soil carbonates and other lines of evidence), they came to comprise a substantial part of the diet of at least some mammalian grazers. Indeed, once C4 grass became abundant, different taxa began to specialize on them. There is no reason to assume that some genera of Miocene mammals (e.g., Tragoportax, a mixed feeder with strong grazing habits) in the Mediterranean region would not have used a new dietary resource such as C4 grasses had they been abundant.

It seems that the most likely cause for a limited C4 vegetation development may be related to the biome configuration of the late Miocene-Pliocene in the Iberian region. Pollen records indicate low percentages (10–15%) of grasses, belonging to the Poaceae family, during the late Miocene and the Pliocene (Jiménez-Moreno, pers. comm. 2012). Pollen analyses are not able to distinguish between C3 and C4 grasses, but if we assume that the percentage of C4 plants estimated by Urban et al. [98] for the early Miocene Rubielos de Mora Basin (20–40%) was maintained in the late Miocene and Pliocene, the final percentage of C4 grasses may have not been enough as to be recorded on mammalian tooth enamel δ13C values.

Conclusions

Long stratigraphic sequences of isotopic data from mammalian tooth enamel are not frequently analyzed due to gaps in the terrestrial fossil record. Such studies are important since they can reveal modifications in paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic factors in terrestrial settings during critical intervals in Earth history. Here, we used stable isotope analysis of a succession of mammals from 18 localities in Spain ranging in age from 11.1 to 0.8 Ma to reconstruct environmental and climatic changes during the late Neogene and early Quaternary. In general, tooth enamel δ13C values indicate that analyzed taxa may have occupied woodland to mesic C3 grassland and in some cases, open woodland to xeric C3 grassland, with no evidence of significant C4 consumption in any of the genera we studied. An increase in δ13C values between MN9 and MN10 appears to correspond to the Middle Vallesian Crisis, a faunal turnover that led to the replacement of humid-adapted taxa by taxa more adapted to drier conditions. A significant decrease in δ13C values during MN14 and MN15 is probably linked to the Pliocene Warm Period (with an associated increase in moisture), whereas the higher δ13C values from MN16 onwards may have been a consequence of the increased aridity in Europe related to the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation. The MAT pattern estimated using tooth enamel δ18OPO4 values agrees well with the thermal trend based on palynological records, rodent assemblage structure, and other isotopic studies from the Iberian Peninsula, with a gradual drop in MAT from MN13 onwards in response to the progressive cooling observed since the Middle Miocene and culminating in the Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to L. Alcalá and E. Espílez (Fundación Conjunto Paleontológico de Teruel-Dinópolis, Teruel) and P. Pérez (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC, Madrid) for kindly providing access to the studied material. S. D. Matson (University of Minnesota, now at Boise State University), and D. Andreasen, J. Lehman and J. Karr (University of California Santa Cruz) are acknowledged for help with isotopic analyses. We are grateful to G. Jiménez-Moreno (Universidad de Granada) for valuable information about Iberian pollen records, and J. Morales (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC) for clarification about the diet of some taxa and valuable comments that helped to improve the manuscript. We also thank the editor R.J. Butler for manuscript management.

Supporting Information

Site, MN, age (Ma), signature, family, taxa, tooth, δ13CCO3 (‰ VPDB), δ18OCO3 (‰ VSMOW) and δ18OPO4 (‰ VSMOW) values for the whole set of fossil mammals from the Iberian Peninsula. Age from Domingo et al. [16, unpublished data]. In the “Tooth” column: M = molar, P = premolar, superscript = upper teeth, subscript = lower teeth.

(XLS)

δ13Cenamel (‰ VPDB) values of the whole set of Iberian mammalian fossil tooth enamel. 1δ13Cdiet (‰ VPDB) calculated by using the offset of 14,1‰ between δ13Cenamel and δ13Cdiet proposed by Cerling and Harris [39]. 2δ13CatmCO2 (‰ VPDB) is from Tipple et al. [40]. 3δ13Cdiet, meq (‰ VPDB) was calculated using equation (2) (see text) and using the modern δ13CatmCO2 (‰ VPDB) of -8‰.

(XLS)

Equations used to calculate δ18Ow values from mammalian tooth enamel δ18OPO4 values.

(XLS)

Statistical analyses comparing different mammalian taxa per MN. Student-t test was used for those MNs where we sampled two genera, whilst ANOVA test was used for those MNs with more than 2 genera. Significant differences are highlighted in bold.

(XLS)

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the UCM, Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Plan Nacional I+D project CGL2009-09000/BTE and Plan Nacional I+D and MNCN-CSIC project CGL2010-19116/BOS) and by a Personal Investigador de Apoyo contract (Comunidad de Madrid) to LD, postdoctoral fellowships (Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología-FECYT and Spanish Ministerio de Educación) to LD and MSD and a UCSC postdoctoral fellowship to LD. This work is a contribution from the research groups UCM-CAM 910161 “Geologic Record of Critical Periods: Paleoclimatic and Paleoenvironmental Factors” and UCM-CAM 910607 “Evolution of Cenozoic Mammals and Continental Palaeoenvironments”. Some sampled teeth were found in excavations conducted by L. Alcalá with the authorization of the Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural del Gobierno de Aragón and supported by the FOCONTUR Project (Research Group E-62, Gobierno de Aragón). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E, Billups K (2001) Trends, Rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292: 686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haug GH, Ganopolski A, Sigman DM, Rosell-Mele A, Swann GEA, et al. (2005) North Pacific seasonality and the glaciation of North America 2.7 million years ago. Nature 433: 821–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vizcaíno M, Rupper S, Chiang JCH (2010) Permanent El Niño and the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciations: Mechanism and comparison with other hypotheses, Paleoceanography. 25: PA2205. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haug GH, Tiedemann R, Zahn R, Ravelo AC (2001) Role of Panama uplift on oceanic freshwater balance. Geology 29: 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edwards EJ, Osborne CP, Strömberg CAE, Smith SA, C4 Grasses Consortium (2010) The origins of C4 grasslands: integrating evolutionary and ecosystem science. Science 328: 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strömberg CAE (2011) Evolution of Grasses and Grassland Ecosystems. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 39: 517–544. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ehleringer JR, Sage RF, Flanagan LB, Pearcy RW (1991) Climate change and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Trends Ecol Evol 6: 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krijgsman WJ, Hilgen FJ, Raffi I, Sierro FJ, Wilson DS (1999) Chronology, causes and progression of the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature 400: 652–655. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rouchy JM, Caruso A (2006) The Messinian salinity crisis in the Mediterranean basin: a reassessment of the data and an integrated scenario. Sediment Geol 188–189: 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hernández Fernández M, Álvarez Sierra MA, Peláez-Campomanes P (2007) Bioclimatic analysis of rodent palaeofaunas reveals severe climatic changes in Southwestern Europe during the Plio-Pleistocene. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 251: 500–526. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiménez-Moreno G, Fauquette S, Suc J-P (2010) Miocene to Pliocene vegetation reconstruction and climate estimates in the Iberian Peninsula from pollen data. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 162: 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Dam JA (2006) Geographic and temporal patterns in the late Neogene (12-3 Ma) aridification of Europe: The use of small mammals as paleoprecipitation proxies. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 238: 190–218. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Böhme M, Winklhofer M, Ilg A (2011) Miocene precipitation in Europe: Temporal trends and spatial gradients. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 304: 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz de Galdeano CM (1996) Tertiary tectonic framework of the Iberian Peninsula. In: Friend F, Dabrio CJ, editors. Tertiary Basins of Spain: The stratigraphic record of crustal kinematics. World and regional Geology 6. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.9–14.

- 15.Andeweg B (2002) Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Iberian Peninsula: causes and effects of changing stress fields. PhD Thesis. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. 178 p.

- 16. Domingo MS, Alberdi MT, Azanza B (2007) A new quantitative biochronological ordination for the Upper Neogene mammalian localities of Spain. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 255: 361–376. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mein P (1975) Résultats du groupe de travail des vertébrés: biozonation du Néogène méditerranéen à partir des mammifères. In: Senes J, editor. Report on Activity of the Regional Committee on Mediterranean Neogene Stratigraphy, Working Groups, Bratislava. pp.77–81.

- 18.Mein P (1979) Rapport d’Activité du Groupe de Travail vertebres. Mise a jour de la biostratigraphie du Neogene basée sur les mammifères. Ann. Géol. Pays Hellén. Tome hors série, fasc., vol. III, 1367–1372.

- 19.Mein P (1990) Updating of MN zones. In: Lindsay EH, Fahlbusch V, Mein P, editors. European Neogene Mammal Chronology. New York: Plenum Press. pp.73–90.

- 20.Mein P (1999) European Miocene mammal biochronology. In: Rössner GE, Heissig K, editors. The Miocene Land Mammals of Europe. Munich: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp.25–38.

- 21. de Bruijn H, Daams R, Daxner-Höck G, Fahlbusch V, Ginsburg L, et al. (1992) Report of the RCMNS working group on fossil mammals, Reisenburg 1990. Newsl Stratigr 26 (2/3): 65–118. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gómez Cano AR, Hernández Fernández M, Álvarez-Sierra MA (2011) Biogeographic provincialism in rodent faunas from the Iberoccitanian Region (southwestern Europe) generates severe diachrony within the Mammalian Neogene (MN) biochronologic scale during the Late Miocene. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 307: 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Dam J, Alcalá L, Alonso Zarza A, Calvo JP, Garcés M, et al. (2001) The Upper Miocene mammal record from the Teruel–Alfambra region (Spain). The MN system and continental stage/age concepts discussed. J Vertebr Paleontol 21: 367–385. [Google Scholar]

- 24. van der Meulen AJ, García-Paredes I, Álvarez-Sierra MA, van den Hoek Ostende LW, Hordijk K, et al. (2012) Updated Aragonian biostratigraphy: small mammal distribution and its implications for the Miocene European Chronology. Geol. Acta 10: 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee-Thorp JA, van der Merwe NJ (1987) Carbon isotope analysis of fossil bone apatite. S Afr J Sci 83: 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cerling TE, Wang Y, Quade J (1993) Expansion of C4 ecosystems as an indicator of global ecological change in the late Miocene. Nature 361: 344–345. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koch PL, Zachos J, Dettman D (1995) Stable isotope stratigraphy and paleoclimatology of the Paleogene Bighorn Basin (Wyoming, USA). Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 115: 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koch PL, Diffenbaugh NS, Hoppe KA (2004) The effects of late Quaternary climate and pCO2 change on C4 plant abundance in the south-central United States. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 207: 331–357. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Domingo L, Grimes ST, Domingo MS, Alberdi MT (2009) Paleoenvironmental conditions in the Spanish Miocene–Pliocene boundary: isotopic analyses of Hipparion dental enamel. Naturwissenschaften 96: 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Domingo L, Cuevas-González J, Grimes ST, Hernández Fernández M, López-Martínez N (2009) Multiproxy reconstruction of the paleoclimate and paleoenvironment of the Middle Miocene Somosaguas site (Madrid, Spain) using herbivore tooth enamel. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 272: 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Domingo L, Koch PL, Grimes ST, Morales J, López-Martínez N (2012) Isotopic paleoecology of mammals and the Middle Miocene Cooling event in the Madrid Basin (Spain). Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 339–341: 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koch PL (1998) Isotopic reconstruction of past continental environments. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 26: 573–613. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch PL (2007) Isotopic study of the biology of modern and fossil vertebrates. In: Michener R, Lajtha K, editors. Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science, 2nd Edition. Boston: Blackwell Publishing. 99–154.

- 34. Bryant JD, Froelich PN (1995) A model of oxygen isotope fractionation in body water of large mammals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 59: 4523–4537. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kohn MJ (1996) Predicting animal δ18O: accounting for diet and physiological adaptation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 60: 4811–4829. [Google Scholar]

- 36. O’Neil JR, Roe LJ, Reinhard E, Blake RE (1994) A rapid and precise method of oxygen isotope analysis of biogenic phosphate. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 43: 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bassett D, MacLeod KG, Miller JF, Ethington RL (2007) Oxygen isotopic composition of biogenic phosphate and the temperature of Early Ordovician seawater. Palaios 22: 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kohn MJ (2010) Carbon isotope compositions of terrestrial C3 plants as indicators of (paleo)ecology and (paleo)climate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 19691–19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cerling TE, Harris JM (1999) Carbon isotope fractionation between diet and bioapatite in ungulate mammals and implications for ecological and paleoecological studies. Oecologia 120: 347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tipple BJ, Meyers SR, Pagani M (2010) Carbon isotope ratio of Cenozoic CO2: A comparative evaluation of available geochemical proxies. Paleoceanography 25: PA3202. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rozanski K, Araguás-Araguás L, Gonfiantini R (1993) Isotopic patterns in modern global precipitation. In: Geophysical Monograph Swart PK, Lohmann KC, McKenzie J, Savin S, editors. Climate Change in continental isotopic records. 78: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haywood AM, Sellwood BW, Valdes PJ (2000) Regional warming: Pliocene (3 Ma) paleoclimate of Europe and the Mediterranean. Geology 28: 1063–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fauquette S, Suc J-P, Jiménez-Moreno G, Micheels A, Jost A, et al.. (2007) Latitudinal climatic gradients in the Western European and Mediterranean regions from the Mid-Miocene (c. 15 Ma) to the Mid-Pliocene (c. 3.5 Ma) as quantified from pollen data. In: Williams M, Haywood AM, Gregory FJ, Schmidt DN, editors. Deep–Time Perspectives on Climate Change: Marrying the Signal from Computer Models and Biological Proxies. The Micropalaeontological Society, Special Publications. London: The Geological Society. pp.481–502.

- 44. Micheels A, Bruch AA, Eronen J, Fortelius M, Harzhauser M, et al. (2011) Analysis of heat transport mechanisms from a Late Miocene model experiment with a fully-coupled atmosphere–ocean general circulation model. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 304: 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Böhme M (2003) The Miocene Climatic Optimum: evidence from ectothermic vertebrates of Central Europe. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 195: 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jiménez-Moreno G, Suc J-P (2007) Middle Miocene latitudinal climatic gradient in western Europe : evidence from pollen records. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 253: 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernández Fernández M, Salesa MJ, Sánchez IM, Morales J (2003) Paleoecología del género Anchitherium von Meyer, 1834 (Equidae, Perissodactyla, Mammalia) en España: evidencias a partir de las faunas de macromamíferos. Coloquios de Paleontología 1: 253–280 vol. ext.

- 48. Hernández Fernández M, Alberdi MT, Azanza B, Montoya P, Morales J, et al. (2006) Identification problems of arid environments in the Neogene-Quaternary mammal record of Spain. J Arid Environ 66: 585–608. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kohn MJ, Cerling TE (2002) Stable isotope compositions of biological apatite. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 48: 455–488. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zazzo A, Lécuyer C, Sheppard SMF, Grandjean P, Mariotti A (2004) Diagenesis and the reconstruction of paleoenvironments: A method to restore original δ18O values of carbonate and phosphate from fossil tooth enamel. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 68: 2245–2258. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Longinelli A, Nuti S (1973) Revised phosphate-water isotopic temperature scale. Earth Planet Sci Lett 19: 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bryant JD, Koch PL, Froelich PN, Showers WJ, Genna BJ (1996) Oxygen isotope partitioning between phosphate and carbonate in mammalian apatite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 60: 5145–5148. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Iacumin P, Bocherens H, Mariotti A, Longinelli A (1996) Oxygen isotope analyses of coexisting carbonate and phosphate in biogenic apatite: a way to monitor diagenetic alteration of bone phosphate? Earth Planet Sci Lett 142: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bender MM (1971) Variations in the 13C/12C ratios of plants in relation to the pathway of photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation. Phytochemistry 10: 1239–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 55. O’Leary MH (1988) Carbon isotopes in photosynthesis. BioScience 38: 328–336. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT (1989) Carbon isotopic discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 40: 503–537. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ehleringer JR, Monson RK (1993) Evolutionary and ecological aspects of photosynthetic pathway variation. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 24: 411–439. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hayes JM (2001) Fractionation of Carbon and Hydrogen Isotopes in Biosynthetic Processes. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 43: 225–277. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Friedli H, Lotscher H, Oeschger H, Siegenthaler U, Stauver B (1986) Ice core record of the 13C/12C ratio of atmospheric CO2 in the past two centuries. Nature 324: 237–238. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Marino BD, McElroy MB (1991) Isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2 inferred from carbon in C4 plant cellulose. Nature 349: 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kohn MJ, McKay MP, Knight JL (2005) Dining in the Pleistocene-Whós on the menu? Geology 33: 649–652. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Feranec R, García N, Díez JC, Arsuaga JL (2010) Understanding the ecology of mammalian carnivorans and herbivores from Valdegoba cave (Burgos, northern Spain) through stable isotope analysis. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 297: 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Matson SD, Rook L, Oms O, Fox DL (2012) Carbon isotopic record of terrestrial ecosystems spanning the Late Miocene extinction of Oreopithecus bambolii, Baccinello Basin (Tuscany, Italy). J Hum Evol 63: 127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agustí J, Antón M (2002) Mammoths, sabertooths and hominids. New York: Columbia University Press.

- 65. Levin NE, Cerling TE, Passey BH, Harris JM, Ehleringer JR (2006) A stable isotope aridity index for terrestrial environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 11201–11205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Merceron G, Blondel C, Brunet M, Sen S, Solounias N, et al. (2004) The late Miocene paleoenvironment of Afghanistan as inferred from dental microwear in artiodactyls. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 207: 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bibi F, Savas-Güleç E (2008) Bovidae (Mammalia: Artiodactyla) from the Late Miocene of Sivas, Turkey. J Vertebr Paleontol 28: 501–519. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Merceron G, de Bonis L, Viriot L, Blondel C (2005) Dental microwear of fossil bovids from northern Greece: paleoenvironmental conditions in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Messinian. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 217: 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Merceron G, Zazzo A, Spassov N, Geraads D, Kovachev D (2006) Bovid paleoecology and paleoenvironments from the Late Miocene of Bulgaria: Evidence from dental microwear and stable isotopes. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 241: 637–654. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rivals F, Athanassiou A (2008) Dietary adaptations in an ungulate community from the late Pliocene of Greece. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 265: 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cerling TE, Harris JM, MacFadden BJ, Leakey MG, Quade J, et al. (1997) Global vegetation change through the Miocene/Pliocene boundary. Nature 389: 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tassy P (1994) Les Proboscidiens (Mammalia) fossiles du rift occidental, Ouganda. In: Senut B, Pickford M, editors. Geology and Palaeobiology of the Albertine Rift Valley, Uganda-Zaïre, Vol. II. Palaeobiology. Orleáns: CIFEG Occasional Publications. pp.217–257.

- 73. Solounias N, Moelleken SMC, Plavcan JM (1995) Predicting the diet of extinct bovids using masseteric morphology. J Vertebr Paleontol 15: 795–805. [Google Scholar]