Abstract

The high mobility group A1 gene (HMGA1) has been previously implicated in breast carcinogenesis, and is considered an attractive target for therapeutic intervention because its expression is virtually absent in normal adult tissue. Other studies have shown that knockdown of HMGA1 reduces the tumorigenic potential of breast cancer cells in vitro. Therefore, we sought to determine if silencing HMGA1 can affect breast cancer development and metastatic progression in vivo. We silenced HMGA1 expression in the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 using an RNA interference vector, and observed a significant reduction in anchorage-independent growth and tumorsphere formation, which respectively indicate loss of tumorigenesis and self-renewal ability. Moreover, silencing HMGA1 significantly impaired xenograft growth in immunodeficient mice, and while control cells metastasized extensively to the lungs and lymph nodes, HMGA1-silenced cells generated only a few small metastases. Thus, our results show that interfering with HMGA1 expression reduces the tumorigenic and metastatic potential of breast cancer cells in vivo, and lend further support to investigations into targeting HMGA1 as a potential treatment for breast cancer.

Keywords: HMGA1, breast cancer, knockdown, xenograft, metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most frequent type of cancer and a leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide [1–3]. The proteins of the high mobility group A (HMGA) family have been previously implicated in breast carcinogenesis [4]. These are non-histone, DNA-binding proteins often referred to as architectural transcription factors. They contain basic A-T hook domains that mediate binding to the minor groove of AT-rich regions of chromosomal DNA. Upon binding to DNA, HMGA proteins regulate gene expression by organizing the transcriptional complex through protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions (reviewed in [5–7]). The HMGA family includes the products of the HMGA1 and HMGA2 genes. Of these, HMGA1 can generate three different protein isoforms through alternative splicing (HMGA1a, b and c). HMGA1a and HMGA1b are the most abundant isoforms, and differ by only 11 amino acids that are present in HMGA1a but not in HMGA1b [4]. HMGA1 is expressed almost exclusively during embryonic development [8], but has been found to be abnormally expressed in several types of cancer, including leukemia [9], pancreatic [10, 11], thyroid [12], colon [13], breast [14–16], lung [17], ovarian [18], endometrial [19], prostate [20], and head and neck cancer [21]. Several studies have also shown that overexpression of HMGA1 induces transformation both in vitro and in animal models (reviewed in [6, 7]).

The causal role of HMGA1 in breast cancer development and metastasis is supported by studies in cell lines [14, 22, 23] as well as by the analysis of clinical specimens [15, 16]. For example, elevated HMGA1 protein expression has been reported in breast carcinomas and hyperplastic lesions with cellular atypia, in contrast with normal breast tissue where HMGA1 was not detected [15, 16]. Similarly, HMGA1 overexpression has been observed in human breast cancer cell lines, with the highest levels in known metastatic lines, such as Hs578T and MDA-MB-231 [14, 22, 23]. Moreover, exogenous overexpression of HMGA1a was shown to induce transformation of the human non-tumorigenic mammary myoepithelial cell line Hs578Bst in vitro [14] and to increase the metastatic ability of MCF7 breast cancer cells in vivo [22].

Conversely, decreasing HMGA1 expression in Hs578T breast cancer cells was shown to cause a reduction in anchorage-independent growth, which is a typical feature of cancer cells [14]. HMGA1 is considered an attractive target for therapeutic intervention because its expression is virtually absent in normal adult tissue and knockdown of HMGA1 has been shown to interfere with the tumorigenic growth of multiple cancer cell lines [6, 7]. We therefore sought to determine if silencing HMGA1 can affect breast cancer development and metastatic progression in vivo using a human xenograft mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, transfections and proliferation assays

The MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection, and cultured in DMEM (Cellgro 10-013), supplemented with 10% FBS and 5 μg/ml gentamicin. Cells were propagated for two weeks, aliquoted in media supplemented with 5% DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen. Each aliquot was used for less than six months. MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Stable transfectants were selected by adding 50 μg/ml of blasticidin to the media, and propagated in media without blasticidin. Anchorage-independent growth was assessed on soft agar as previously described [17]. Tumorsphere formation from single cell suspensions was assessed using MammoCult media (STEMCELL Technologies) in ultralow adherence plates (Corning). Spheres were counted using an inverted microscope after seven days of growth. Secondary tumorspheres were generated from single cells suspensions obtained by enzymatic digestion of the primary tumorspheres using 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen). All kits and reagents were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

HMGA1 silencing construct

The HMGA1 silencing construct pHMGA1-394-EmGFP-miR was generated using the BLOCK-iT Pol II miR RNAi with EmGFP system (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Briefly, a silencing microRNA (miRNA) RNA interference (RNAi) oligonucleotide was designed based on the reference sequence NM_145899.1, using Invitrogen’s RNAi designer. The HMGA1 target sequence with the best rank score (5′-AGCGAAGTGCCAACACCTAAG) was incorporated into a pre-miRNA sequence and cloned into the pcDNA6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR vector using the reagents and competent E. coli supplied with the kit. Five E. coli clones were isolated and the constructs sequenced. One construct with verified miRNA sequence was selected for transfection. A vector harboring a non-targeting miRNA sequence provided with the kit was used as control.

Gene expression Analysis

RNA expression was assessed by quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) after reverse transcription. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) applying the on-column DNase treatment. The amount and quality of the RNA were verified by measuring the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. Reverse transcription was performed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, and duplex qPCR of the resulting cDNA was performed on a 7500 Real Time PCR System, using the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, and the Human RPLP0 Endogenous Control (Applied Biosystems). The TaqMan primers and probes for HMGA1 were previously described [19]. Reverse Transcriptase negative (RT−) samples were analyzed in parallel to verify the absence of contaminating genomic DNA. All qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate. Protein expression was assessed by western blot. Cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) with added cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Applied Science), and run on 4%–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris Gels using NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen). Gels were blotted on PVDF membranes and HMGA1 was detected using 0.3 μg/ml of a goat primary antibody (EB06959, Everest Biotech); Beta Actin (loading control) was detected using a 1:1000 dilution of rabbit primary antibody (4967, Cell Signaling Technology). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). All kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Animal experiments

NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J (NOD SCID) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, and maintained in Johns Hopkins AAALAC accredited facilities, with all procedures approved by the ACUC. All efforts were made to minimize suffering. Mice were injected subcutaneously at the inguinal mammary fat pad with 2 × 106 cells in 50 μl of serum-free media (one injection per mouse). Tumor growth was monitored for 10 weeks. Mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal Avertin overdose, followed by cardiac perfusion with heparinized PBS, then 10% neutral buffer formalin for fixation. Tissues were routinely processed for paraffin embedment, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

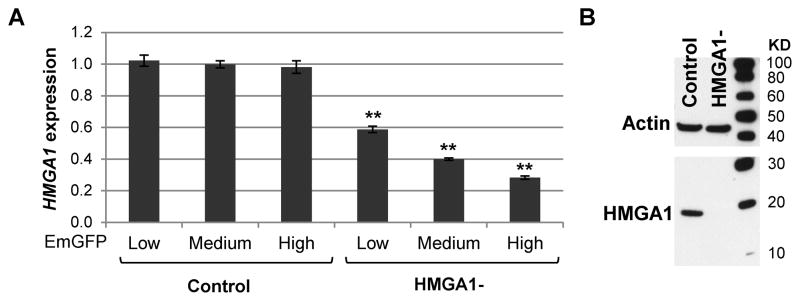

We generated an HMGA1-silencing construct that uses microRNA (miRNA) for RNA interference (RNAi), and co-expresses the fluorescent molecule EmGFP (co-cistronic) for easy detection of the transfected cells (pHMGA1-394-EmGFP-miR). We selected the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 because it was previously shown to overexpress HMGA1 [14], and it is tumorigenic in immunodeficient mice. Stable, polyclonal MDA-MB-231 transfectants were generated, and sorted by flow cytometry. We isolated three fractions with different degrees of EmGFP fluorescence, which were analyzed for HMGA1 expression by qRT-PCR. The analysis showed that knockdown of HMGA1 correlated with fluorescence intensity in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the silencing vector (Figure 1A), as it was expected since the sequences for the miRNA and EmGFP are co-cistronic. There was no decrease in HMGA1 mRNA in cells transfected with the control vector (Figure 1A). This allowed us to select a cell population with efficient knockdown of HMGA1 without isolating individual clones. The fractions with the highest fluorescence were expanded and further analyzed by western blot. HMGA1 was detected exclusively in the control cells (Figure 1B), confirming the efficient knockdown of HMGA1 by this silencing construct.

Figure 1. HMGA1 knockdown in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.

HMGA1 expression analysis by qRT-PCR (A), and western blot (B) in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the HMGA1 silencing vector (HMGA1-). Bars represent means ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates; **P<0.001 by Student’s t-test. Expression values are relative to the average of the control samples.

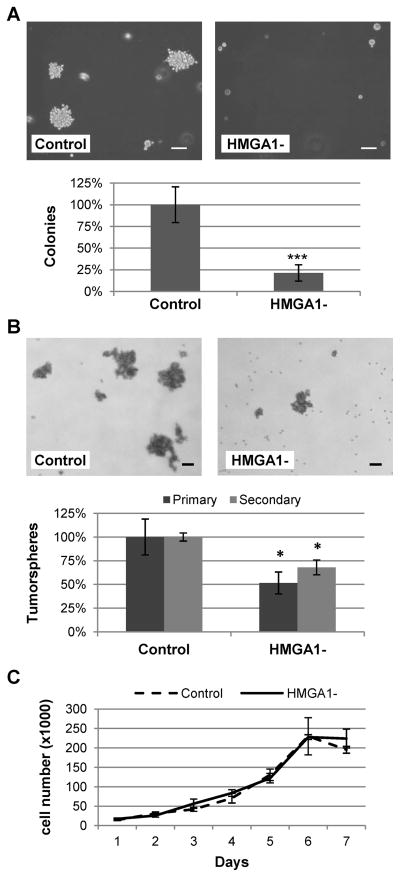

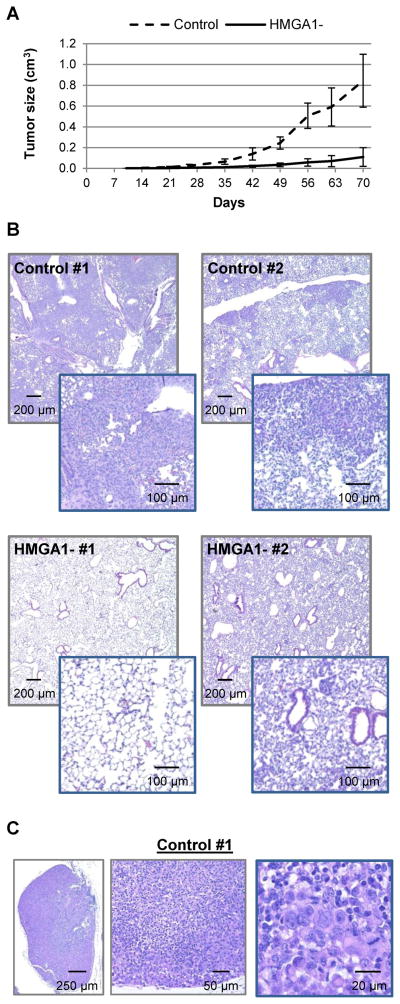

Decreasing HMGA1 expression has been shown to inhibit transformation in vitro in various established cancer cells lines [6, 7], including Hs578T breast cancer cells [14]. Thus, we tested our HMGA1-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells for anchorage-independent growth, which is indicative of the tumorigenic and metastatic potentials of cancer cells [24], and the ability to form tumorspheres, which reflects stem/progenitor cell properties [25, 26]. Knockdown of HMGA1 reduced colony formation on soft agar by 80%, (P<0.001; Figure 2A) and formation of primary tumorspheres by almost 50% (P=0.019, Figure 2B). The effect of HMGA1 knockdown on the formation of secondary tumorspheres was less pronounced but still significant (Figure 2B; P=0.047). Since we used a polyclonal cell population, the reduced response in the secondary tumorspheres may result from the selection of clones with less efficient HMGA1 knockdown during the formation of the primary tumorspheres. Cell growth in standard tissue culture conditions was not affected (Figure 2C), indicating that silencing HMGA1 does not cause a general inhibition of cell proliferation in this cell line but rather affects specific growth features associated with transformation, similarly to what was previously observed in Hs578T cells [14]. To investigate if knockdown of HMGA1 affects breast cancer development and metastatic progression in vivo, we injected HMGA1-silenced and control MDA-MB-231 cells subcutaneously at the inguinal mammary fat pads of NOD SCID immunodeficient mice. Each cohort consisted of 10 mice, injected at one single site with 2 × 106 cells. Control MDA-MB-231 cells generated large tumors as expected. In contrast, growth of HMGA1-silenced xenografts was significantly inhibited (p<0.0001; two-way anova) indicating that HMGA1 is necessary for in vivo tumorigenesis in this breast cancer cell line (Figure 3A). Tumor growth was monitored for 10 weeks. Post-mortem examination showed that the animals injected with control MDA-MB-231 cells had extensive necrosis of the primary tumors, numerous extensive lung metastases exceeding 1 mm in diameter (Figure 3B), and distant metastases exceeding 5 mm diameter in axillary and contralateral prefemoral (subiliac) lymph nodes (Figure 3C). Animals injected with HMGA1-silenced cells had less necrosis, far less lung metastases (Figure 3B) and only one lymph node metastasis less 2 mm in diameter was observed. This striking difference in metastasis may be the result of a general inhibition of tumorigenesis since the primary tumors generated by HMGA1-silenced cells are significantly smaller than those formed by control cells. However, HMGA1 overexpression is known to affect the transcription of many genes involved in metastatic progression [22, 27] and has recently been associated with repression of MTSS1, which encodes the metastasis suppressor protein 1 [28]. Thus, it is possible that knockdown of HMGA1 in our model is affecting metastatic potential through specific pathways and not only because of the reduced tumor growth.

Figure 2. Knock down of HMGA1 inhibits anchorage-independent growth and tumorspheres formation in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.

Colonies on soft agar (A), tumorspheres (B) and cell growth in standard tissue culture conditions (C) of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the HMGA1 silencing vector (HMGA1-) or the non-silencing vector (control). Size bar = 100 μm. Colonies larger than 100 μm and tumorspheres larger than 50 μm were counted. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated twice. Value shown are means ± SD; *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 by Student’s t-test.

Figure 3. Knockdown of HMGA1 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells impairs tumorigenesis and metastasis in immunodeficient mice.

A) Primary tumor size in immunodeficient mice injected with control or HMGA1-silenced (HMGA1-) MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells; values shown are means ± SD; n = 10. B) Histological analysis shows extensive metastases in the lungs of mice injected with control cells, and only small metastases or intravascular neoplastic emboli in the lungs of animals injected with HMGA1-silenced cells; two representative mice from each cohort, and two magnifications for each slide are shown. C) Representative lymph node from one mouse injected with control cells; the lymph node is expanded and largely effaced by neoplastic cells.

In summary, we show that interfering with HMGA1 expression reduces breast tumorigenesis in vivo. Taken together with the existing literature, our results indicate that HMGA1 could be a viable target for the development of new therapeutic strategies for breast cancer treatment.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Overexpression of HMGA1 has been previously implicated in breast carcinogenesis.

An RNAi-based HMGA1-silencing construct with co-expression of EmGFP was generated.

HMGA1-silenced MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were generated.

Knockdown of HMGA1 impairs anchorage-independent growth and tumorsphere formation.

Knockdown of HMGA1 impairs xenograft growth and metastasis in immunodeficient mice.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (062544_YCSA), and The National Institutes of Health (P30 CA006973). The funding sources had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase no 10 [internet] lyon, france: International agency for research on cancer; 2010. [accessed on 16 mar 2013]. available from: Http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2013. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JWW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peluso S, Chiappetta G. High-mobility group A (HMGA) proteins and breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2010;5:81–85. doi: 10.1159/000297717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves R, Beckerbauer L. HMGI/Y proteins: Flexible regulators of transcription and chromatin structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1519:13–29. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedele M, Fusco A. HMGA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resar LM. The high mobility group A1 gene: Transforming inflammatory signals into cancer? Cancer Res. 2010;70:436–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fusco A, Fedele M. Roles of HMGA proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:899–910. doi: 10.1038/nrc2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Y, Sumter TF, Bhattacharya R, Tesfaye A, Fuchs EJ, Wood LJ, Huso DL, Resar LM. The HMG-I oncogene causes highly penetrant, aggressive lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice and is overexpressed in human leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3371–3375. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe N, Watanabe T, Masaki T, Mori T, Sugiyama M, Uchimura H, Fujioka Y, Chiappetta G, Fusco A, Atomi Y. Pancreatic duct cell carcinomas express high levels of high mobility group I(Y) proteins. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3117–3122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hristov AC, Cope L, Di Cello F, Reyes MD, Singh M, Hillion JA, Belton A, Joseph B, Schuldenfrei A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Resar LM. HMGA1 correlates with advanced tumor grade and decreased survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:98–104. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiappetta G, Tallini G, De Biasio MC, Manfioletti G, Martinez-Tello FJ, Pentimalli F, de Nigris F, Mastro A, Botti G, Fedele M, Berger N, Santoro M, Giancotti V, Fusco A. Detection of high mobility group I HMGI(Y) protein in the diagnosis of thyroid tumors: HMGI(Y) expression represents a potential diagnostic indicator of carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4193–4198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiappetta G, Manfioletti G, Pentimalli F, Abe N, Di Bonito M, Vento MT, Giuliano A, Fedele M, Viglietto G, Santoro M, Watanabe T, Giancotti V, Fusco A. High mobility group HMGI(Y) protein expression in human colorectal hyperplastic and neoplastic diseases. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:147–151. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1033>3.3.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolde CE, Mukherjee M, Cho C, Resar LM. HMG-I/Y in human breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;71:181–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1014444114804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiappetta G, Botti G, Monaco M, Pasquinelli R, Pentimalli F, Di Bonito M, D’Aiuto G, Fedele M, Iuliano R, Palmieri EA, Pierantoni GM, Giancotti V, Fusco A. HMGA1 protein overexpression in human breast carcinomas: Correlation with ErbB2 expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7637–7644. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flohr AM, Rogalla P, Bonk U, Puettmann B, Buerger H, Gohla G, Packeisen J, Wosniok W, Loeschke S, Bullerdiek J. High mobility group protein HMGA1 expression in breast cancer reveals a positive correlation with tumour grade. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:999–1004. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillion J, Wood LJ, Mukherjee M, Bhattacharya R, Di Cello F, Kowalski J, Elbahloul O, Segal J, Poirier J, Rudin CM, Dhara S, Belton A, Joseph B, Zucker S, Resar LM. Upregulation of MMP-2 by HMGA1 promotes transformation in undifferentiated, large-cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1803–1812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masciullo V, Baldassarre G, Pentimalli F, Berlingieri MT, Boccia A, Chiappetta G, Palazzo J, Manfioletti G, Giancotti V, Viglietto G, Scambia G, Fusco A. HMGA1 protein over-expression is a frequent feature of epithelial ovarian carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1191–1198. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tesfaye A, Di Cello F, Hillion J, Ronnett BM, Elbahloul O, Ashfaq R, Dhara S, Prochownik E, Tworkoski K, Reeves R, Roden R, Ellenson LH, Huso DL, Resar LM. The high-mobility group A1 gene up-regulates cyclooxygenase 2 expression in uterine tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3998–4004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamimi Y, van der Poel HG, Denyn MM, Umbas R, Karthaus HF, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA. Increased expression of high mobility group protein I(Y) in high grade prostatic cancer determined by in situ hybridization. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5512–5516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rho YS, Lim YC, Park IS, Kim JH, Ahn HY, Cho SJ, Shin HS. High mobility group HMGI(Y) protein expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:76–81. doi: 10.1080/00016480600740571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeves R, Edberg DD, Li Y. Architectural transcription factor HMGI(Y) promotes tumor progression and mesenchymal transition of human epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:575–594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.575-594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WM, Guerra-Vladusic FK, Kurakata S, Lupu R, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. HMG-I(Y) recognizes base-unpairing regions of matrix attachment sequences and its increased expression is directly linked to metastatic breast cancer phenotype. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5695–5703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guadamillas MC, Cerezo A, Del Pozo MA. Overcoming anoikis--pathways to anchorage-independent growth in cancer. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3189–3197. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MS. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponti D, Costa A, Zaffaroni N, Pratesi G, Petrangolini G, Coradini D, Pilotti S, Pierotti MA, Daidone MG. Isolation and in vitro propagation of tumorigenic breast cancer cells with stem/progenitor cell properties. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5506–5511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans A, Lennard TW, Davies BR. High-mobility group protein 1(Y): Metastasis-associated or metastasis-inducing? J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:86–99. doi: 10.1002/jso.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuldenfrei A, Belton A, Kowalski J, Talbot CC, Jr, Di Cello F, Poh W, Tsai HL, Shah SN, Huso TH, Huso DL, Resar LM. HMGA1 drives stem cell, inflammatory pathway, and cell cycle progression genes during lymphoid tumorigenesis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:549. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]