Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To examine perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs regarding barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening, and to identify potential interventional strategies to promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i.

Design

Exploratory, qualitative.

Setting

Community-based settings in Hawai’i.

Sample

20 Filipino men, 40 years old or older

Methods

Focus group discussions were tape-recorded, transcribed, and content analysis performed for emergent themes.

Main Research Variables

Perceptions regarding prostate cancer, barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening, and culturally-relevant interventional strategies

Findings

Perceptions of prostate cancer included fatalism, hopelessness, and dread. Misconceptions regarding causes of prostate cancer, such as frequency of sexual activity, were identified. Barriers to prostate cancer screening included lack of awareness of the need for screening, reticence to seek healthcare when feeling well, fear of cancer diagnosis, financial issues, time constraints, and embarrassment. Presence of urinary symptoms, personal experience with family or friend who had cancer, and receiving recommendations from a healthcare provider regarding screening were facilitators for screening. Potential culturally-relevant interventional strategies to promote prostate cancer screening included screening recommendations from health professionals and cancer survivors; radio/television commercials and newspaper articles targeted to the Filipino community; informational brochures in Tagalog, Ilocano and/or English; and interactive, educational forums facilitated by Filipino multilingual, male healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

Culturally-relevant interventions are needed that address barriers to prostate cancer screening participation and misconceptions about causes of prostate cancer.

Implications for Nursing

Findings provide a foundation for future research regarding development of interventional strategies to promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino men.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in Hawai’i (American Cancer Society Hawai’i Pacific, 2003). Each year, approximately 700 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer, and over 100 men die from the disease in Hawai’i. Among Hawai’i residents, Filipino men are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage prostate cancer and to experience lower survival rates than all other racial and ethnic subgroups (American Cancer Society Hawai’i Pacific, 2003). With repeated use of current prostate cancer screening techniques (Prostate Specific Antigen blood test [PSA] and Digital Rectal Examination [DRE]), the majority of prostate cancers are detected at a clinically localized stage (Brawley, Ankerst & Thompson, 2009). Therefore, a high rate of advanced-stage prostate cancer among an ethnic minority group may be indicative of low levels of participation in prostate cancer screening by members of that group. A qualitative approach was employed to explore the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening among Filipino men residing in Hawai’i. Since Filipino Americans constitute the second largest and fastest growing subpopulation of Asians residing in United States (Ghosh, 2003), and since there is limited information regarding the perceptions of prostate cancer and the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening in this group, the information gained from this study will serve as a foundation for addressing an important disparity in health outcomes for this growing population.

Background

Stage at diagnosis is an important predictor of cancer survival. Nationally, the five-year relative survival for men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer approaches 100 percent (Jemal, Siegel, Ward, Hao, Xu, & Thun, 2009). In contrast, the five-year relative survival for men with metastatic prostate cancer is only 32 percent (Jemal et al., 2009). Among Hawai’i residents, Filipino men (24.3%) were most likely to be diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer, followed by native Hawaiians (21.9%), Japanese (17.6%), Caucasians (16.9%), and Chinese (15.9%) (American Cancer Society Hawai’i Pacific, 2003).

Early detection through screening is an important intervention to reducing ethnic disparity in morbidity and mortality from prostate cancer. Currently, the American Cancer Society recommends that healthcare providers should discuss the benefits and limitations of prostate cancer screening with men, age 50 years or older and who have a life expectancy of at least 10 years and who are at average risk of prostate cancer, and those men who indicate a preference for screening following this discussion should be offered an annual PSA test and DRE. Men at high risk, such as African-Americans and men with a first-degree relative diagnosed with prostate cancer before age 65 years, should have this discussion with their healthcare provider beginning at 45 years of age. Further, men with two or more first-degree relatives diagnosed with prostate cancer before age 65 years, should have this discussion at age 40 years (Smith, Cokkinides, & Brawley, 2009). Results of the 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) conducted in Hawai’i revealed that of all men interviewed age 40 years and older, Filipino males were least likely to report ever having a PSA test (28.2%) and DRE examination (51.6%) done as compared to other ethnic groups (Hawai’i State Department of Health, n.d.). This lack of participation in prostate cancer screening could provide a possible explanation as to why Filipino men are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer.

Reasons for the low participation in prostate cancer screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i are unclear. To date, after conducting a thorough computer search using PubMed, Cochrane, and CINAHL databases, there are no published studies that have specifically examined the barriers, attitudes, and beliefs of Filipino men about prostate cancer screening. In studies conducted among African-American men, barriers to participation in prostate cancer screening include “too many things going on in their lives”, limited knowledge about the disease, lack of access to screening services, embarrassment of DRE examination, fear of cancer diagnosis, and distrust of the government and medical professionals (Forrester-Anderson, 2005; McDougall, Adams, & Voelmeck, 2004; Meade, Calvo, Rivera, & Baer, 2003; & Odedina, Scrivens, Emanuel, LaRose-Pierre, Brown, & Nash, 2004). Whether these barriers are similar or different among Filipino men is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs of Filipino men in Hawai’i regarding barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening, and to identify potential interventional strategies to promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino men.

Methods

Given the limited information available regarding the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening among Filipino men, an exploratory qualitative design using focus groups was employed. The institutional review board at the University of Hawai’i approved all study procedures and patient contact materials. Written consent forms were available in both English and in Ilocano. Each participant was able to choose the consent form written in the language they preferred. All participants selected and signed the English version of the consent form.

Sample, Setting and Procedures

Filipino men aged 40 years and older, residing in Hawai’i, were recruited to participate in focus groups. Exclusion criterion was self-reported history or current diagnosis of prostate cancer. Potential participants were recruited from churches, community centers, and various Filipino social and professional organizations using IRB-approved flyers, word of mouth, community outreach workers, and community nurses on two Hawaiian islands (Oahu and Kauai) in order to provide a broad geographic representation of the state’s Filipino population.

A total of five focus groups were conducted with each focus group consisting of 3 to 6 Filipino men. Each focus group session had at least two research staff (a group leader and a recorder) present, and both bilingual research staff were fluent in Ilocano or Tagalog and English. Participants were given the option to select the language (Ilocano, Tagalog, or English) in which the focus group sessions were to be conducted. Because of the different Filipino dialects spoken by the group participants, participants chose English as the preferred language to use during all five focus group sessions.

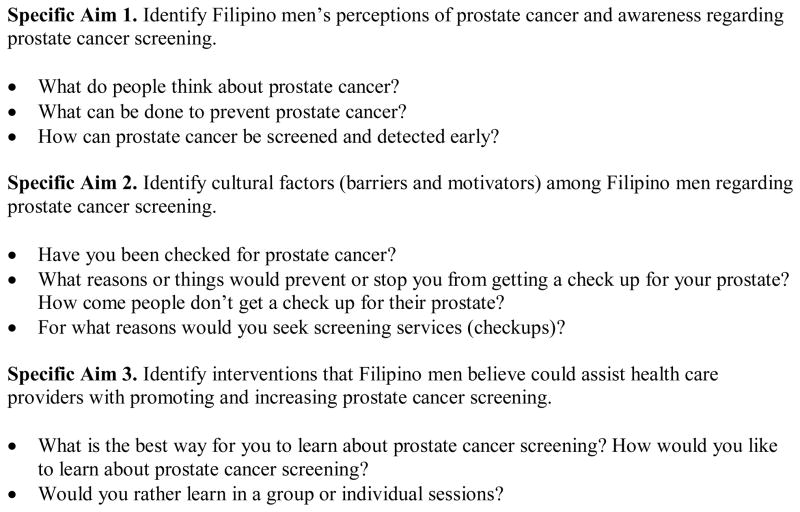

After explaining the study to the participants, written consent was obtained and a demographic questionnaire was completed by each participant. Participants were identified only by initials and code numbers in order to protect their confidentiality. The discussion in each focus group session was guided by a series of questions designed to elicit information regarding Filipino men’s perceptions of prostate cancer and their awareness of prostate cancer screening, to identify cultural factors that may represent barriers or facilitators to prostate cancer screening, and to identify potential interventions that will increase awareness and promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino residents of Hawai’i (see Figure 1). In addition, following each focus group session, participants had the opportunity to take part in a question and answer session regarding prostate cancer, in which the group leader provided factual information about prostate cancer screening, risk factors for prostate cancer, and health promotion strategies known to be associated with decreased risk of prostate cancer (e.g., lycopene in the diet and avoidance of obesity). Each session lasted between 1 and 2 hours. Each participant received $25 in compensation for their time. All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 1.

Focus Group Questions

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report participant characteristics. Content analysis was performed manually by each member of the research team. Transcripts were reviewed multiple times by five members of the research team and recurring phrases or concepts from the transcripts were identified and labeled with codes (topic coding). Similar concepts were then grouped into categories (analytic coding). The data were then analyzed for emerging themes using the identified concepts and categories (Richards & Morse, 2007). Results of the analysis were compared, as were the interpretations of the individual team members. In addition, data were periodically reviewed by the researchers and 5 of the 20 participants in an interactive process to assure accuracy of the analysis and provide a mutually agreed-upon final analysis.

Results

Participants (n = 20, mean age = 56 ± 8 years) were all Filipino males, age 40 or older, residing in Hawai’i, who had no history of prostate cancer. Demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 56 ± 8 | |

|

| ||

| Length of residency in United States (years) | 23 ± 11 | |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Filipino | 20 (100) | |

| Mixed | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

| Single, never married | 1 (5) | |

| Married | 18 (90) | |

| Living together/not married | 1 (5) | |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| High school degree | 1 (5) | |

| Some college/trade school | 2 (10) | |

| College degree | 14 (70) | |

| Graduate degree | 3 (15) | |

|

| ||

| Religious denomination | ||

| Catholic | 15 (75) | |

| Protestant | 3 (15) | |

| Jehovah’s Witness | 1 (5) | |

| Unknown | 1 (5) | |

|

| ||

| Medical insurance | ||

| Yes | 20 (100) | |

| No | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||

| Hawaiian island residency | ||

| Oahu | 14 (70) | |

| Kauai | 3 (15) | |

| Molokai | 2 (10) | |

| Maui | 1 (5) | |

Data were clustered into four topical areas for analysis (Perceptions of Prostate Cancer, Barriers to Prostate Cancer Screening, Facilitators to Prostate Cancer Screening, and Ideas for Interventions to Promote Prostate Cancer Screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i) based on the questions used to guide the focus group discussions (see Figure 1). Within each of these four topical areas, numerous concepts were identified. Related concepts were grouped into categories, assisting in the identification of emerging over-arching themes. The major themes and categories from each of the four topical areas are summarized below.

Perceptions of Prostate Cancer: “There’s no Cure”

Negative beliefs and attitudes regarding cancer: Fatalism, dread, hopelessness

When asked to share their thoughts regarding cancer in general, at least some participants in each group expressed a sense of fatalism (“Cancer is like a death sentence”); some also described fear or dread (“You dread it. It’s a debilitating disease”), and others described hopelessness (“It’s the deeper way the person thinks when he or she hears that ‘I have cancer’ …. For example, I just can’t live anymore because I have this”) and isolation (“They just isolate themselves and wait until death”). Some described medical treatment for cancer as too expensive and futile (“The medical expenses is so high and you die anyway so what’s the use”) and something to be feared (“Even if there are some treatment, even the treatment itself is kind of, people fear it, you know. Because it’s like you say those people been treated for cancer and because like they have them go through much pain and suffering”). Others expressed concern that people who have cancer, especially males who are heads of households, are a burden to their families (“The head of the family you’re supposed to be supporting the children; not them supporting you. So sometimes they say, ‘So be it, I’ll die’”). First-generation Filipinos were described as particularly likely to have a fatalistic attitude toward cancer (“If you’re the first generation or you just came from the Philippines, and you just arrive here and you get the cancer, your mentality will be, it’s depressing. There’s no cure; nothing.”), while second-generation Filipinos were described as more knowledgeable and aware of treatment and resources (“The next generation after that, the kids who are growing here, they have more knowledge of the insurance that the people just won’t give up…”), and were more likely to have believe that cancer is potentially curable (“Most of the cancer, used to be death sentence, but not any more because it can be cured. A lot of cancers can be cured because of the technologies”), particularly with early detection (“I also heard that there’s a cancer of the prostate and they said that it’s curable if detected early”).

Lack of knowledge regarding cancer

Lack of information regarding cancer was described as a particular problem for first-generation Filipinos (“Filipinos are we’re low in information because of education”) who may ignore information (“Yeah, and the first information about this kind of stuff…They just ignore it”) as a result of a fatalistic attitude associated with cancer (“they don’t want to talk about death”). Second generation Filipinos were described as having improved access to information, which is facilitated by access to computers (“Generations after that, it’s more advanced …Especially at this age that we can go to the Internet”).

Misinformation regarding causes of prostate cancer

Several participants expressed the belief that prostate cancer was caused by the frequency of sexual activity. Some thought that prostate cancer was due to excessive sex or promiscuous behavior (“Oversexed” “Prostate cancer, that’s what you get because you’re a playboy, yeah”), and may be considered by some as punishment (“It’s kind of a curse. Because … they are promiscuous”), while others voiced that prostate cancer may be related to lack of sex (“Too little or no sex at all, like how you get kidney stones when you don’t pee. If you don’t release, the fluid inside gets hard”). Other misinformation regarding the causes of prostate cancer included urinary retention (“You wanted to go pee but … maybe that’s one of the cause”), contamination (“when the thing is contaminated or something or become enlarged”), stress (“stress has some connection to that”), culture (“I think it may be cultural”), and heavy lifting (“some people say that that cause the enlargement you’re lifting too much stuff”). Some participants indicated that they had no knowledge regarding the etiology (“Honestly, I don’t know the causes of prostate cancer”).

Risk factors for prostate cancer

Risk factors for prostate cancer identified by participants included family history (“Some of the cancer is like it’s in the family. You can inherit.”), age (“I think as you age your body breaks down.”), diet (“I think it’s also in what you eat”), excessive alcohol (“drinking too much”) and being overweight (“One thing about cancer, overweight people get the most.”).

Beliefs about cancer prevention

Participants identified diet and exercise as playing an important role in cancer prevention (“Live a healthier life to prevent it”). Specific foods were identified as helping to prevent cancer, including tomatoes (identified by one participant as containing lycopene), fish, and vegetables. Participants also identified education (“I guess it’s just education of the public”) and regular check-ups (“I think that men have check up every year”) as important cancer prevention strategies.

Barriers to Prostate Cancer Screening: “There’s no Awareness”

Barriers to prostate cancer screening identified by participants included lack of awareness of the need for screening (“there’s no awareness of prostate disease”), reticence to seek health care when feeling well (“Filipinos are by nature like they don’t really go to see a doctor just for the sake of having a check up” “The only time when I go and see a doctor is when I really feel sick already”), postponing health care (“Even though the doctor tell them to go and have some kind of examination. Then they just … postpone and postpone until … Filipino mentality”), fear of being diagnosed with cancer/fear of death (“Because I’m scared to know” “You’re scared to die”), financial issues (“lack of money”), time constraints, both for the patient (“busy”) and the healthcare provider (“Because the doctor only see them for three seconds”), religious beliefs (“some kind of religious belief … that if that’s how God wants him to do then”), and embarrassment (“really embarrassing especially the assistant is a woman”). Some stated there was no reason not to be screened (“There’s no reason why to stop me. If I need to go, I would go”). Self-reported history of prostate cancer screening of the study participants is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant self-reported prostate cancer screening history

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ever screened for prostate cancer? | ||

| Yes | 10 | 50% |

| No | 8 | 40% |

| No response | 2 | 10% |

| Reason for screening | ||

| Healthcare provider recommendation | 2 | 20% |

| Symptoms | 1 | 10% |

| Family history | 1 | 10% |

| Patient requested screening | 1 | 10% |

| No reason given | 5 | 50% |

| Reason for not screening | ||

| Healthcare provided did not recommend | 2 | 25% |

| No reason given | 6 | 75% |

Facilitators to Prostate Cancer Screening: “My Doctor Advised Me To”

Facilitators to prostate cancer screening identified by participants included the presence of urinary symptoms, such as frequency, hesitancy, nocturia, and urinary retention (“They will see the doctor because they have something … they wanted to be checked. That’s more of a Filipino mentality”), concern regarding kidney failure (“sometimes you are thinking about kidney failure too”), having appropriate information (“You know what to ask”), having an established relationship with a healthcare provider (“I visit my doctor regularly … so just like we have a very open dialogue … we discuss”), having regular check-ups (“go to the doctor regularly and be tested”), and receiving recommendations from a healthcare professional regarding screening (“Most Filipinos are mind followers. If the doctor will say have to do it” “I go check my prostate every year. My doctor advise me to”).

Ideas for Interventions to Promote Prostate Cancer Screening: “Overcoming Barriers”

Participants shared several ideas regarding potential interventional strategies to promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i. Lack of awareness of the need for screening was identified as a significant barrier that could potentially be overcome using multiple strategies, including recommendations for screening by credible authorities, such as employers (“Because a lot of us work and so you know they should check. They should, hey, you guys have this test make sure you get it”), and health plans (“The insurance … you have to get this test and stuff. I think that would spread the word”), and the inclusion of information at Filipino community events and health fairs. Informational sessions with professional facilitators, similar to the focus group setting, were also suggested as potentially helpful in promoting screening (“Like set up some discussions like we have now”) and most participants voiced a preference for group meetings rather than one-on-one consultations (“It’s actually better in a group. Some people have different experiences. They can share”) preferably led by a Filipino male (“It’s a male part that a woman doesn’t have. So it’s better male”) healthcare professional fluent in various Filipino dialects (“Filipino that can speak our language”).

Participants also suggested development of simple brochures (“Just specific symptoms. Very simple”), television and radio commercials, and newspaper articles regarding prostate cancer screening targeted to the Filipino community and distributed over Filipino media, such as cable channels and newspapers. Suggestions for commercial messages included a prostate cancer survivor, possibly a celebrity (“Even this guy is famous but he caught cancer and he was cured”) or an everyday person (“A prostate cancer survivor … and they’re not ashamed”), a grandfather and grandson (“Maybe some people, oh, I’m already 65 and already 70, like I enjoyed life. So what if I died tomorrow. So maybe you can add something. Hey, think about your grandchildren. Have more time to enjoy with your grandchildren, yeah”), and a Filipino physician (“We all Filipinos … the doctor is Filipino not different nationality”). Participants voiced that the messages should be made available in Ilocano, Tagalog, and English (“You want to cater to more people, why not translate it to the different common languages”), possibly combining more than one language on a single brochure (“one side is English and one side is. Or one English and in the bottom Ilocano”).

Discussion

The current high rates of presentation of advanced-stage prostate cancer among Filipino men in Hawai’i underscore the importance of understanding the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening for this growing subpopulation. Several key items emerged as important considerations in planning potential interventions to improve adherence to prostate cancer screening among Filipinos in Hawai’i.

Factors that should be taken into consideration in planning and developing interventions to promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i include perceptions about prostate cancer (particularly the fatalistic beliefs held by most first-generation Filipinos), and the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening identified by the study participants. For example, participants identified that a recommendation from a healthcare provider was a powerful facilitator for prostate cancer screening. In a study of predictors of cancer screening among Filipino and Korean immigrants in the United States (Maxwell, Bastani, & Warda, 2000), ever having a medical check-up when no symptoms were present was identified as the strongest predictor of cancer screening, and this predictor was stronger among Filipino than Korean immigrants, suggesting that Filipinos are either more likely to get a recommendation for cancer screening at a health check-up and/or are more likely to follow through with recommended screening. Either conclusion supports the important role of the healthcare provider in facilitating cancer screening among Filipinos. Therefore, consideration should be given to developing interventions to increase awareness among healthcare professional regarding the importance of their role in facilitating prostate cancer screening among Filipino males in Hawai’i. Additionally, the other variable consistently associated with adherence to cancer screening in the Maxwell et al. (2000) study was percent of lifetime spent in the United States, with increased adherence associated with increased time spent in the United States, pointing to the potential need to develop differing interventional strategies for first- versus second-generation Filipinos.

Participants also identified the potential usefulness of community forums/group information sessions led by Filipino healthcare providers, and of the distribution of educational brochures written in Tagalog, Ilocano and/or English in increasing awareness of the need for prostate cancer screening among Filipino males in Hawai’i. The potential role of peer interaction fostered by community meetings and information sessions could be facilitated by community action groups, such as the Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research and Training (AANCART). Other potential interventional strategies include development of radio and television commercials featuring prostate cancer survivors who are Filipino celebrities or even “everyday” Filipino people who have survived prostate cancer.

Several barriers to prostate cancer screening that emerged from the data in this study, such as lack of awareness and knowledge, negative beliefs and fears, and seeking healthcare only when symptoms appear, are similar to those that have been identified in other ethnic and racial minority groups, such as African Americans and Hispanics (Forrester-Anderson, 2005; McFall, Hamm, & Volk, 2006; Meade et al., 2003). In addition, some of the potential interventional strategies, such as group discussions, television and radio advertising, newspaper articles, and involvement of employers in dissemination of information, have also been previously identified as potential strategies for other minority ethnic groups (McFall et al., 2006; Meade et al., 2003). However, several issues unique to the Hawai’i’s Filipino population were also identified, such as male heads of households with cancer being considered a burden to their families, and the tendency to postpone recommended healthcare, dubbed the “Filipino mentality.”

Study Limitations

Study participants consisted of a small convenience sample of Filipino men residing in Hawai’i drawn from churches, community centers, and various Filipino social and professional organizations, and may not be representative of the larger population of Filipino male residents of Hawai’i. In addition, those males volunteering to participate in a focus group regarding prostate health may be overly representative of those willing to talk about sensitive issues in a group situation and thus the data gathered may not reflect the full spectrum of barriers and facilitators to prostate screening present among Filipino men in Hawai’i. The range of potential interventions may also not be fully representative of those interventions most appropriate for the entire population of Filipino males living in Hawai’i. Strengths of the study include the inclusion of participants from 4 of the 7 inhabited Hawaiian islands, conduct of the focus groups in the participants’ preferred language, and confirmation of some emerging themes with studies in other ethnic/racial minority groups.

In summary, many of the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening identified in this study are similar to those that have been identified in other ethnic and racial minority groups. However, this study also contributes some novel information regarding the barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i. The results suggest several potential culturally-appropriate interventions to promote prostate cancer screening among Filipino men residing in Hawai’i, including targeted education for Filipino healthcare providers regarding the importance of their role in facilitating screening. It is important to note that while some findings presented here are consistent with those from other minority groups and others appear to represent newly identified knowledge, these results were drawn from a small sample and should be considered preliminary. Barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening may be different for other groups of Filipinos living in Hawai’i but not represented in the sample, and therefore further study is needed to confirm or extend these findings.

Nursing Implications.

Findings of this study contribute to nursing science by identifying new information regarding knowledge and perceptions of prostate cancer, and barriers and facilitators to prostate cancer screening among Filipino men residing in Hawai’i, thus providing a foundation for future research. Information elicited from this study may help nurses and other healthcare providers to design and develop effective, culturally-sensitive interventions that could promote awareness and participation in prostate cancer screening among Filipino men in Hawai’i, and which could also potentially contribute to the reduction in health disparities currently seen in this group.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH Research Grant P20 NR008360 funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research and the National Center for Minority and Health Disparities. No financial relationships to disclose. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Forum or the Oncology Nursing Society.

Contributor Information

Francisco A. Conde, Queen’s Cancer Center.

Wendy Landier, University of Hawai’i School of Nursing.

Dianne Ishida, University of Hawai’i School of Nursing.

Rose Bell, University of Hawai’i School of Nursing.

Charlene F. Cuaresma, Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research, and Training.

Jane Misola, University of Hawai’i School of Nursing.

References

- American Cancer Society Hawai’i Pacific. Hawai’i cancer facts & figures 2003–2004. Honolulu, HI: American Cancer Society Hawai’i Pacific, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brawley OW, Ankerst DP, Thompson IM. Screening for prostate cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59(4):264–273. doi: 10.3322/caac.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester-Anderson IT. Prostate cancer screening perceptions, knowledge and behaviors among African American men: focus group findings. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16(4 Suppl A):22–30. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh C. Healthy People 2010 and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders: defining a baseline of information. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(12):2093–2098. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawai’i State Department of Health. 2008 State of Hawaii behavioral risk factor surveillance system. n.d Retrieved August 17, 2009, from http://hawaii.gov/health/statistics/brfss/brfss2008/demo08.html.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Warda US. Demographic predictors of cancer screening among Filipino and Korean immigrants in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall GJ, Jr, Adams ML, Voelmeck WF. Barriers to planning and conducting a screening: prostate cancer. Geriatric Nursing. 2004;25:336–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall SL, Hamm RM, Volk RJ. Exploring beliefs about prostate cancer and early detection in men and women of three ethnic groups. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;61(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CD, Calvo A, Rivera MA, Baer RD. Focus groups in the design of prostate cancer screening information for Hispanic farmworkers and African American men. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30(6):967–975. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.967-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odedina FT, Scrivens J, Emanuel A, LaRose-Pierre M, Brown J, Nash R. A focus group study of factors influencing African-American men’s prostate cancer screening behavior. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96:780–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L, Morse JM. User’s guide to qualitative methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. Coding; pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2009: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59(1):27–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]