This retrospective institutional experience from the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center reports the overall response rate, R0 resection rate, progression-free survival, and safety/toxicity of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiation in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. FOLFIRINOX demonstrated substantial activity in patients with LAPC, although recurrences after resection and toxicities raise important questions about how to best treat these patients.

Keywords: FOLFIRINOX, Locally advanced pancreatic cancer, Neoadjuvant, R0 resection, Chemoradiation

Abstract

The objective of our retrospective institutional experience is to report the overall response rate, R0 resection rate, progression-free survival, and safety/toxicity of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil [5-FU], oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and leucovorin) and chemoradiation in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC). Patients with LAPC treated with FOLFIRINOX were identified via the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center pharmacy database. Demographic information, clinical characteristics, and safety/tolerability data were compiled. Formal radiographic review was performed to determine overall response rates (ORRs). Twenty-two patients with LAPC began treatment with FOLFIRINOX between July 2010 and February 2012. The ORR was 27.3%, and the median progression-free survival was 11.7 months. Five of 22 patients were able to undergo R0 resections following neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiation. Three of the five patients have experienced distant recurrence within 5 months. Thirty-two percent of patients required at least one emergency department visit or hospitalization while being treated with FOLFIRINOX. FOLFIRINOX possesses substantial activity in patients with LAPC. The use of FOLFIRINOX was associated with conversion to resectability in >20% of patients. However, the recurrences following R0 resection in three of five patients and the toxicities observed with the use of this regimen raise important questions about how to best treat patients with LAPC.

Implications for Practice:

The prognosis for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer, who constitute about almost a third of patients presenting with a new diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, is quite poor, with a median survival of approximately 1 year. The ideal treatment paradigm for these patients is unclear, but based on the experience with FOLFIRINOX in the metastatic setting, multiple institutions have begun to treat with FOLFIRINOX for patients with locally advanced disease. In this paper, we describe our institutional experience with FOLFIRINOX followed by chemoradiation in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. We provide evidence for substantial activity, with conversion to surgical resectability in more than 20% of patients. We believe that further study is warranted on this promising treatment approach for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is estimated to have affected over 43,000 patients and to have caused 37,000 deaths in the United States in 2012 [1]. Only 10%–20% of patients present with surgically resectable disease, and for patients who undergo surgical resection, the 5-year overall survival rate is 15–20%. Approximately 30% of patients presenting with a new diagnosis of pancreatic cancer lack evidence of systemic metastases and present with locally advanced disease [2, 3], for which median overall survival is approximately 1 year.

The optimal treatment paradigm and the role for chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer is unclear, with no definitive guidance from studies to date on the superiority of chemotherapy versus chemoradiation approaches. With regard to gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine-based chemoradiation, two recent randomized controlled studies reached different conclusions. The Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive and Societe Francophone de Radiotherapie Oncologique trial demonstrated improved overall survival with gemcitabine alone compared with induction chemoradiation followed by gemcitabine chemoradiation employing 5-FU/cisplatin [4]. In contrast, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 4201 trial compared gemcitabine alone with gemcitabine-based chemoradiation, with improved overall survival with the chemoradiation arm (one-sided p = .017), which was accompanied by substantial increases in grade 4/5 toxicities [5]. Both studies did not accrue to planned patient enrollment, hampering the interpretation of results. There have been no randomized trials to assess the potential benefit of initial chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation, although retrospective data support this approach [6, 7]. In addition, some patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer will be rendered resectable by virtue of having an excellent response to therapy [8–10].

The landscape for systemic therapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer has changed significantly with the use of FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil [5-FU], oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and leucovorin). In a randomized phase III study comparing FOLFIRINOX with gemcitabine in 342 chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, FOLFIRINOX was associated with an improved survival, progression-free survival, and response rate. [11]. Based on the data supporting the use of FOLFIRINOX in the metastatic setting, there is great interest in assessing the activity of FOLFIRINOX for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Two important unanswered questions are (a) will the benefit in response rate and overall survival in the metastatic setting translate to patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer? and (b) are curative-intent resections possible in patients who respond to treatment? In this report, we present our institutional experience in patients with exclusively locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with FOLFIRINOX.

Methods

All patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) who began treatment with FOLFIRINOX at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center between July 2010 and February 2012 were identified by searching the cancer center pharmacy database under a minimal risk study approved by the institutional review board. MGH is a National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-designated institution and follows the NCCN definition of unresectable, which includes those with distant metastases, metastases to lymph nodes beyond the resection field, and then varies according to disease location in the head, body, or tail of the pancreas, but including >180 degree encasement of the superior mesenteric artery, unreconstructable superior mesenteric vein or portal vein occlusion, aortic invasion, or celiac encasement [12].

For those patients receiving full-dose FOLFIRINOX, dosing was as per the phase III trial of FOLFIRINOX [11], with 5-FU administered as a bolus of 400 mg/m2, bolus leucovorin 400 mg/m2, followed by continuous infusion at 1200 mg/m2 per day for 46 hours, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, and irinotecan 180 mg/m2. Prophylactic pegfilgrastim was administered to all patients 24 hours after the 46-hour infusion in all cycles containing 5-FU, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan. Although based on clinical status and organ function at the time of starting FOLFIRINOX, choices regarding dosing modifications were determined by the individual treating oncologist. If one of these three drugs was omitted, pegfilgrastim was administered at the discretion of the treating physician. The approach for all patients included neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by chemoradiation. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisted of four cycles of FOLFIRINOX, followed by repeat computed tomography (CT) imaging. If stable disease or better was observed compared with baseline, an additional four cycles of FOLFIRINOX was planned. If repeat CT imaging again revealed stable disease or better, all patients were recommended to undergo chemoradiation. For all patients, treatment was continued until disease progression, patient preference, or limiting toxicities. For patients receiving chemoradiation following neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX, a radiosensitizing chemotherapy, such as continuous infusion 5-FU or capecitabine, was employed along with intensity-modulated radiation therapy delivered to 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions. Multidisciplinary review with radiology, surgery, radiation oncology, and medical oncology was performed for baseline scans and for scans following completion of chemoradiation treatment.

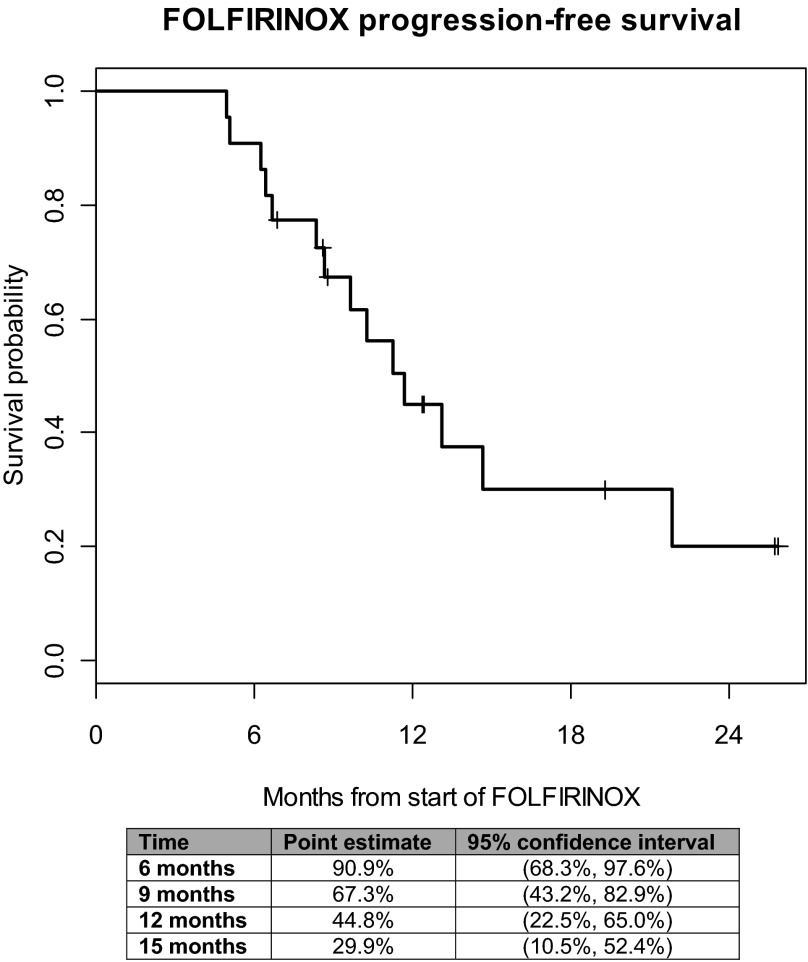

Demographic information, clinical characteristics, safety/tolerability as measured by gradable toxicities, and emergency department visits (or hospitalizations) were tabulated. Formal radiographic review was retrospectively performed to determine overall response rates (ORRs). Patients were assessed for tumor response according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guidelines (RECIST, version 1.1) [13]. The images were consensus-read by two radiologists, with 6 and 15 years experience. We compared measurable target lesions (TLs), which are defined as soft-tissue lesions that could be accurately measured in at least one dimension, with the largest diameter being at least 1 cm or at least 1.5 cm in the short axis for lymph nodes. Progressive disease (PD) was considered when there was at least a 20% increase in the sum of the total size of TLs or the presence of a new unequivocal metastatic disease, partial response (PR) when there was at least a 30% decrease in the total size of TLs, and stable disease (SD) when there was any percent change between +19% and −29% in the sum of the total size of TLs. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of FOLFIRINOX to the earliest of the following: date of radiographic progression (local or metastatic), appearance of metastatic disease at surgical exploration, or death. Patients without radiographic progression were censored at the time of last radiographs. PFS estimates were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method, and Greenwood's formula was used to obtain two-sided 95% confidence intervals. All patients receiving FOLFIRINOX were eligible for toxicity analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize data from the above analyses.

Results

Twenty-two patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer received FOLFIRINOX at the MGH Cancer Center in the 20-month period spanning July 2010 to February 2012. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age of patients was 63 years (range: 49–78 years), including 13 men and 9 women. All patients except one were chemotherapy näive. Fifty-eight percent of patients had pancreatic head/uncinate lesions and 42% had body/tail lesions. Ten of the 22 patients had a biliary stent in place at the start of FOLFIRINOX. All patients with a recorded status in clinic notes had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1. Median follow-up for patients was 19.3 months.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics (n = 22)

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; CA 19–9, carbohydrate antigen 19–9; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

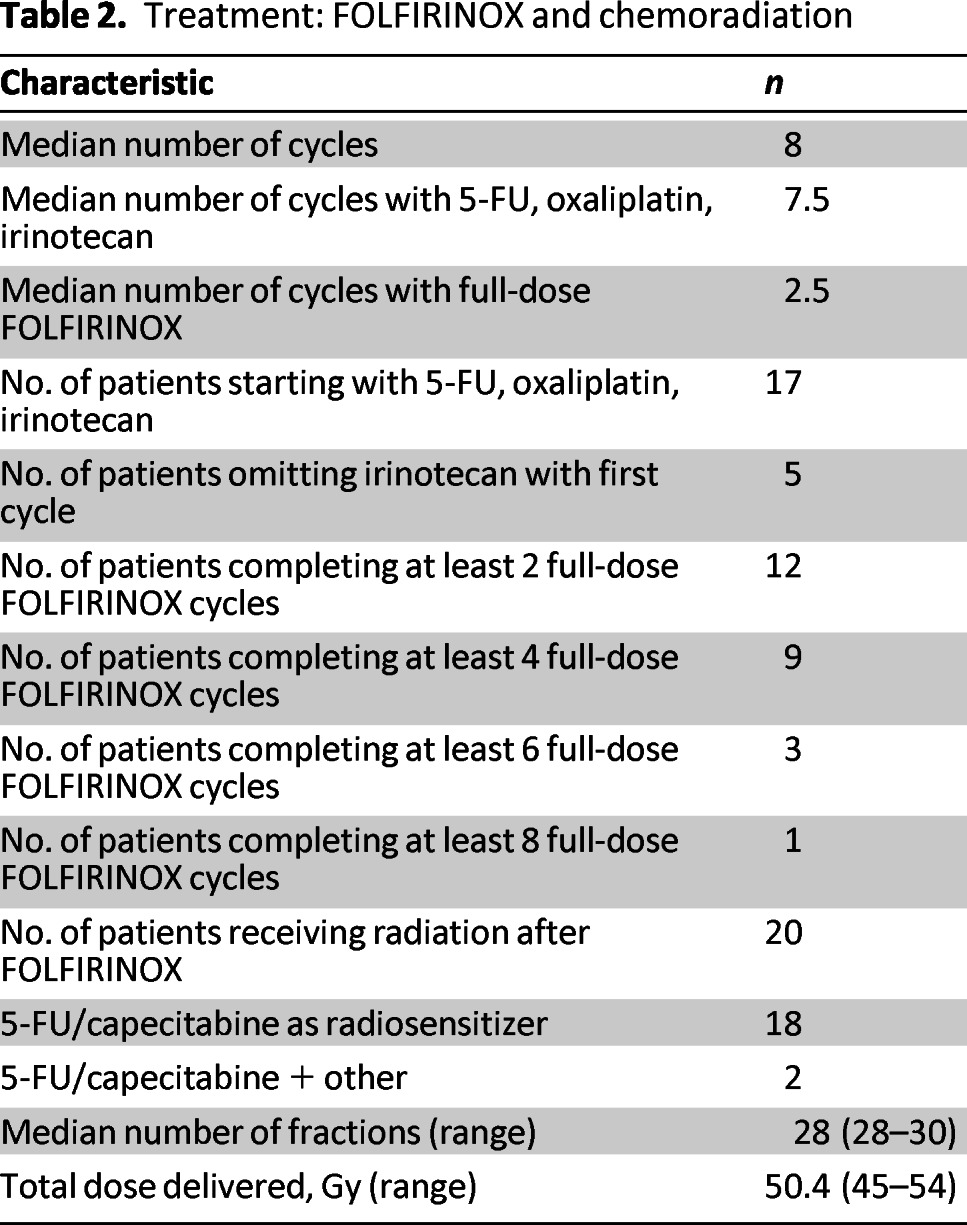

A total of 178 cycles of chemotherapy were given to the 22 patients, of which 156 cycles contained all three active drugs (5-FU, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin). Sixty-six cycles were with full doses of FOLFIRINOX. Five patients were started on FOLFOX during the initial cycle(s) of chemotherapy, with addition of irinotecan to later cycles. An additional five patients were started on FOLFIRINOX, with eventual discontinuation of oxaliplatin or irinotecan. Patients received a median of 8 cycles of FOLFIRINOX, and 7.5 cycles in which all three active drugs were included (Table 2). Patients received a median of 2.5 full-dose FOLFIRINOX cycles. Of the 17 patients who received 5-FU, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin on the first cycle, 13 received full doses of each drug, including the 5-FU bolus of 400mg/m2. Following FOLFIRINOX, all but two patients received fluoropyrimidine-based chemoradiation (Table 2). In the five patients undergoing surgical resections, a median of 8 cycles of FOLFIRINOX were delivered (range 6–8), with a median of 4 full-dose cycles of FOLFIRINOX (range 3–8).

Table 2.

Treatment: FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiation

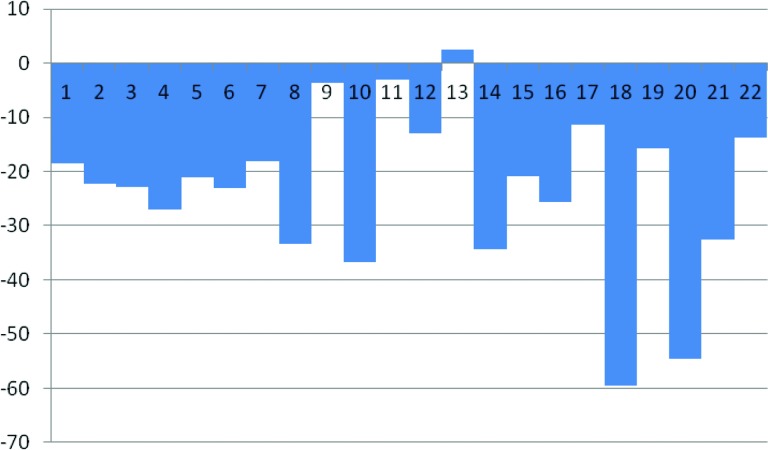

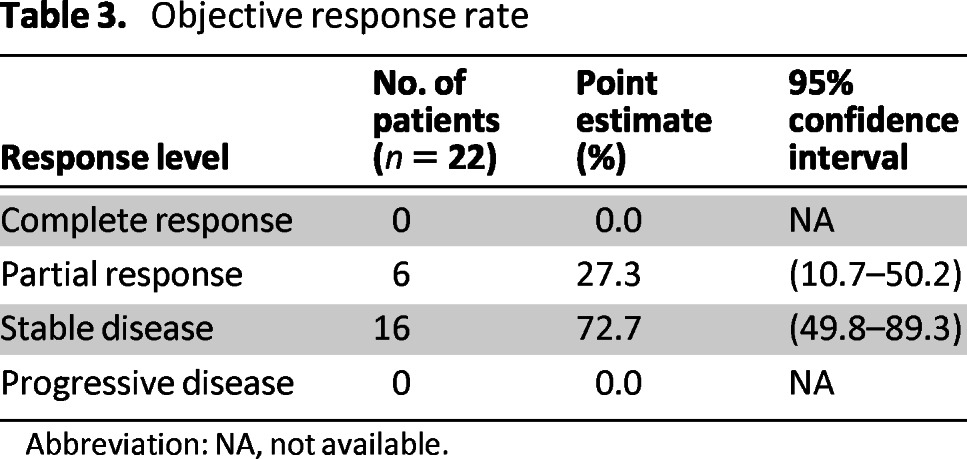

Overall, six nonconfirmed partial responses (PR) were observed in 22 evaluable patients (ORR 27.3%) while on FOLFIRINOX (Table 3). One additional patient had a nonconfirmed partial response following chemoradiation, and another had a nonconfirmed partial response following chemoradiation and intraoperative IORT, for a total of 8 of 22 evaluable patients (ORR 36.4%). In all, 19 of 22 patients had decreases in CA19–9 by 30% or more, and 17 of the 22 had decreases of 50% or more from baseline CA19–9 prior to starting FOLFIRINOX. A total of 13 of 22 patients had ≥20% reductions in target lesion measurements as indicated by the waterfall plot in Figure 1. Following neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX, 12 patients were taken to the operating room for exploration. Five patients underwent R0 resections (Fig. 2), of whom one patient had no remaining evidence of tumor. Seven patients had surgically unresectable disease and six of these patients had intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) administered, with or without palliative hepaticojejunostomy and/or gastrojejunostomy; of the six undergoing IORT, only one patient has experienced progressive disease. Our decision to proceed with IORT was based on the experience of Willett et al. [14], in which the retrospective experience with IORT for unresectable pancreatic cancer at MGH was characterized. The 3-year survival was 7%, with five patients surviving more than 5 years.

Table 3.

Objective response rate

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival.

Figure 2.

Waterfall plot of maximum percent change from baseline scans during FOLFIRINOX treatment.

One patient did not receive IORT due to the discovery of peritoneal and omental implants. Of the five patients who had R0 resections, three have experienced distant recurrence, at a median of 81 days (range: 74–144 days). One patient is now more than 500 days since resection and has no evidence of recurrence. Median progression-free survival for the entire cohort was 11.7 months (95% confidence interval: 8.3–21.8 months; Fig. 2), with 14 of the 22 patients demonstrating local or distant progression thus far. Overall survival was not calculated because only five patients have died since starting FOLFIRINOX.

With regard to tolerability, only events that could be captured and appropriately graded from the medical record were included (Table 4). A total of 7 of the 22 (32%) required hospitalization or emergency department visits during FOLFIRINOX, >50% of which were for non-neutropenic fevers or dehydration/diarrhea. Because three patients were admitted multiple times, there were 12 hospitalization events. Although there were four patients who developed grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, there were no cases of febrile neutropenia. Only two patients discontinued FOLFIRINOX for toxicities related to treatment. In the five patients who underwent R0 resections, the median length of stay was 7 days (range 5–35). Two of the five patients had no postsurgical complications. Two patients had postoperative infections. One patient was readmitted 10 days after discharge with fevers and leukocytosis, although cultures and workup was negative. One of the patients who had a postoperative infection also had to undergo permanent transhepatic drain placement due to multiple biliary strictures after neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiation (transhepatic drains placed during Whipple surgery).

Table 4.

Hospitalization and selected toxicities

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ED, emergency department.

Discussion

This is the largest published series of patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with FOLFIRINOX. Recently, the activity of FOLFIRINOX in patients with borderline or locally advanced pancreatic cancer was reported [15], which included a total of 18 patients, of whom 14 had locally advanced disease. In these 14 patients, four patients proceeded directly to surgery after 3–12 cycles of FOLFIRINOX, and two of these 14 had an R0 resection. An additional three patients underwent R0 resections after completing chemoradiation treatment. Thus, the R0 resection rate in this case series, excluding the patients with borderline resectable disease, was 36% (5 of 14 patients). Our R0 resection rate of 23% (5 of 22 patients) is in the range reported by Hosein et al. [15] and may reflect a new era of converting locally advanced pancreatic cancer into resectable pancreatic cancer with the use of FOLFIRINOX.

Given the superior activity of FOLFIRINOX in comparison with gemcitabine, it is extremely important to establish the activity and toxicity of FOLFIRINOX in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Our experience raises at least four important issues. The first major issue involves the subjective definition of locally advanced and borderline pancreatic cancer. The R0 resection rates range from 8%–64% in 510 patients from 13 studies employing various neoadjuvant chemoradiation protocols for unresectable pancreatic cancer [16]. Despite the large discrepancy in R0 resection rates, overall survival is similar between the studies, suggesting that the extreme heterogeneity in resection rates observed in this meta-analysis is due more to the subjective definition of borderline and locally advanced disease. Our series is restricted to patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer as determined by an experienced pancreatic surgery group. It is critical that future studies separate patients with locally advanced and borderline resectable disease. In addition to evaluating these two categories separately, establishing formal consensus criteria for locally advanced and borderline disease is of critical importance. At present, one institution's locally advanced pancreatic cancer may be considered a borderline resectable patient in another institution. The uneven definition and application of criteria used to assign categories to the radiographic presentation of patients with pancreatic cancer probably introduces the greatest amount of variability in the percentage of patients who can undergo a potential curative resection. There are criteria to define locally advanced and borderline pancreatic cancer, which are defined by NCCN guidelines specifically by location in the pancreatic head, body, or tail [12]. As of yet, however, there has not been complete acceptance of and adoption of these criteria. At MGH, we have a multidisciplinary meeting with radiology, surgery, radiation oncology, and medical oncology, during which the imaging, consisting of a pancreatic-protocol CT, is reviewed in detail to assign a stage based on NCCN criteria. A major criticism of the current study is the lack of an independent review board assessing our adherence to these criteria.

A second important issue involves the contribution and sequencing of chemoradiation following neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX. In our study, with the exception of one patient with progressive disease and another who declined chemoradiation, all patients proceeded to chemoradiation after FOLFIRINOX. In the Hosein et al. study [15], a subset of patients were brought directly to the operating room for attempted resection following maximal response to FOLFIRINOX; interestingly, only half of these patients (two of four patients) were able to have R0 resections. Although chemoradiation may ultimately prove essential for R0 resections, critics argue that this window of time could allow for micrometastatic disease, previously controlled via FOLFIRINOX, to develop. Importantly, our experience suggests that this is an uncommon event. The timing and sequencing of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation is an active debate at all cooperative group meetings.

Third, it is critical to assess the tolerability of FOLFIRINOX specifically in patients with locally advanced disease who often have compromised biliary drainage prior to embarking on a multi-institutional study. With more than 30% of patients requiring an emergency department visit or admission during FOLFIRINOX treatment, this regimen is quite toxic in a patient population that is considered technically incurable. Although a third of these hospitalizations were brief admissions for diarrhea/dehydration, there were two admissions for non-neutropenic bacteremia. Reassuringly, with the use of prophylactic growth factor with all cycles of FOLFIRINOX in this series, there were no cases of febrile neutropenia. Given our experience, upfront dose modification of the FOLFIRINOX regimen might be necessary, particularly in less well-selected populations of patients. Currently, the impact on dose reductions, such as elimination of the 5-FU bolus, is unknown, both in terms of efficacy and toxicity. The reason for the large discrepancy in full-dose FOLFIRINOX cycles in our study (37% of cycles) and the Hosein et al. study (83% of cycles) [15] is unknown, but it may relate to differences in patient selection, including age and performance status. In addition, approximately one-third of patients had borderline disease in the Hosein et al. study, whereas all patients in our study had locally advanced disease. A limitation of this retrospective analysis is that we cannot accurately grade subjective complaints such as peripheral neuropathy, fatigue, and diarrhea from the medical record. Retrospective data on subjective toxicities is inherently incomplete and unreliable and, thus, was not included. Although of clear importance to a discussion of tolerability of a newer chemotherapy regimen such as FOLFIRINOX, an accurate assessment of the frequency and severity of these side effects must be assessed prospectively.

A final and more basic question is whether a patient with initially unresectable disease who achieves an R0 resection after neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX is really curable. Would palliative systemic chemotherapy and/or chemoradiation achieve the same outcome, avoiding the known morbidity and potential mortality of surgical resection? In our series, three of the five patients with an R0 resection developed distance recurrence at a median of 81 days after surgery. Although we share the enthusiasm that neoadjuvant therapy may permit resection for patients with initially unresectable disease, these early results remind us that the vast majority of patients with pancreatic cancer have systemic disease.

Investigation of biomarkers that may allow for prediction of local versus systemic recurrence could prove helpful in decisions regarding chemoradiation for these patients. For example, an autopsy series found a strong association between local recurrence and an intact DPC4 gene [17]. If this finding is corroborated in other larger studies, chemoradiation could be reserved for patients with intact DPC4. Searching for additional biomarkers that might allow for prediction of response to and toxicity from FOLFIRINOX, as well as benefit from chemoradiation, would be helpful in personalizing therapies with ample potential to both improve response and reduce harm.

Our institutional experience with FOLFIRINOX should serve as a template for future clinical trials designed to definitively address the utility of FOLFIRINOX for patients with both locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Currently, we have separate protocols at our institution for patients with clearly resectable disease, borderline resectable disease, and locally advanced disease. The issues regarding integration of FOLFIRINOX into these different stages of disease are critically important in the pancreatic cancer community.

Conclusion

For patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer, FOLFIRINOX possesses substantial activity, and its use was associated with conversion to resectable status in more than 20% of patients. However, recurrent disease was discovered in three of the five patients. There was a significant toxicity signal, with nearly a third of patients requiring at least one emergency department visit or hospitalization. The optimal strategy for treating patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer requires further study.

Acknowledgments

These data were presented in part at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancer Symposium 2012, San Francisco, California.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the accompanying commentary on pages 487–489 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Jason Faris, Theodore Hong, Lawrence Blaszkowsky, Jeffrey Clark, David Ryan

Provision of study materials or patients: Theodore Hong

Collection and/or assembly of data: Jason Faris, Shaunagh McDermott, Alex Guimaraes, Mai Anh Huynh, David Ryan, Theodore Hong

Data analysis and interpretation: Jason Faris, Shaunagh McDermott, Alexander Guimaraes, Jackie Szymonifka, Mai Anh Huyng, Theodore Hong, David Ryan, Lawrence Blaszkowsky

Manuscript writing: Jason Faris, Lawrence Blaszkowsky, Shaunagh McDermott, Alexander Guimaraes, Jackie Szymonifka, Mai Anh Huynh, Cristina Ferrone, Jennifer Wargo, Jill Allen, Lauren Dias, Eunice Kwak, Keith Lillemoe, Sarah Thayer, Janet Murphy, Andrew Zhu, Dushyant Sahani, Jennifer Wo, Jeffrey W. Clark, Carlos Fernandez-Del Castillo, David Ryan, Theodore Hong

Final approval of manuscript: Jason Faris, Lawrence Blaszkowsky, Shaunagh McDermott, Alexander Guimaraes, Jackie Szymonifka, Mai Anh Huynh, Cristina Ferrone, Jennifer Wargo, Jill Allen, Lauren Dias, Eunice Kwak, Keith Lillemoe, Sarah Thayer, Janet Murphy, Andrew Zhu, Dushyant Sahani, Jennifer Wo, Jeffrey W. Clark, Carlos Fernandez-Del Castillo, David Ryan, Theodore Hong

Disclosures

Jason Faris: N-of-One (C/A); Roche (RF); Alexander Guimaraes: Siemens Medical (C/A); Andrew Zhu: Sanofi Aventis, Eisai, Exelixia, Daiichi Sankyo (C/A); Bayer Onyx, Lilly (RF); Theodore Hong: Illumina (C/A); Novartis (RF). The other authors reported no financial relationships.

C/A: Consulting/advisory relationship; RF: Research funding; E: Employment; H: Honoraria received; OI: Ownership interests; IP: Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; SAB: scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philip PA. Locally advanced pancreatic cancer: Where should we go from here? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4066–4068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:607–620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chauffert B, Mornex F, Bonnetain F, et al. Phase III trial comparing intensive induction chemoradiotherapy (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Definitive results of the 2000–01 FFCD/SFRO study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1592–1599. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loehrer PJ, Sr., Feng Y, Cardenes H, et al. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4105–4112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huguet F, Andre T, Hammel P, et al. Impact of chemoradiotherapy after disease control with chemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma in GERCOR phase II and III studies. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:326–331. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan S, Rana V, Janjan NA, et al. Induction chemotherapy selects patients with locally advanced, unresectable pancreatic cancer for optimal benefit from consolidative chemoradiation therapy. Cancer. 2007;110:47–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huguet F, Girard N, Guerche CS, et al. Chemoradiotherapy in the management of locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma: A qualitative systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2269–2277. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arvold ND, Ryan DP, Niemierko A, et al. Long-term outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy before chemoradiation for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:3026–3035. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habermehl D, Kessel K, Welzel T, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation with gemcitabine for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Rad Oncol. 2012;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology; version 2.2012. [Accessed April 16, 2013]. Available at http://www.nccn.org//professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf.

- 13.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willett CG, Del Castillo CF, Shih HA, et al. Long-term results of intraoperative electron beam irradiation (IOERT) for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;241:295–299. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000152016.40331.bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosein PJ, Macintyre J, Kawamura C, et al. A retrospective study of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX in unresectable or borderline-resectable locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morganti AG, Massaccesi M, La Torre G, et al. A systematic review of resectability and survival after concurrent chemoradiation in primarily unresectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:194–205. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1806–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]