This comprehensive literature review was conducted to better understand and discuss issues related to therapeutic recommendations that are particular to older patients with head and neck cancer (HNC). It was found that older patients with HNC do not have worse survival rates but may experience higher treatment-related toxicities than their younger peers, specifically as the intensity of treatment increases, with comorbidities and functional age being better predictors of treatment tolerance and development of toxicities compared with chronological age.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Geriatric oncology, Multimodality therapy, Aged

Learning Objectives

Compare survival and toxicity outcomes of older patients with head and neck cancer with those of their younger cohorts.

Describe the role played by comorbidity, quality of life, and supportive care in the treatment decision and treatment process of older patients with head and neck cancer.

Abstract

The incidence of head and neck cancer (HNC) in the elderly is increasing. The treatment of HNC often includes multimodality therapy that can be quite morbid. Older patients (herein, defined as ≥65 years) with HNC often have significant comorbidity and impaired functional status that may hinder their ability to receive and tolerate combined modality therapy. They have often been excluded from clinical trials that have defined standards of care. Therefore, tailoring cancer therapy for older patients with HNC can be quite challenging. In this paper, we performed a comprehensive literature review to better understand and discuss issues related to therapeutic recommendations that are particular to patients 65 years and older. Evidence suggests that older patients have similar survival outcomes compared with their younger peers; however, they may experience worse toxicity, especially with treatment intensification. Similarly, older patients may require more supportive care throughout the treatment process. Future studies incorporating geriatric tools for predictive and interventional purposes will potentially allow for improved patient selection and tolerance to intensive treatment.

Implications for Practice:

Tailoring therapy for older patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) is challenging. This review article provides physicians with evidence on how older patients may differ from their younger peers. In addition, we offer clinical recommendations to guide oncologists on treatment recommendations and management of older HNC patients.

Introduction

Head and neck cancers (HNC) occur within the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. In 2012, there were an estimated 52,610 new cases of HNC and 11,500 related deaths in the U.S. [1]. Despite the increasing trend of cancer related to human papillomavirus, which primarily affects younger patients [2, 3], HNC remains primarily a cancer of an older population. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, approximately 47% of all patients diagnosed with HNC in the U.S. between 1973 and 2008 were ≥65 [4]. In addition, the incidence of newly diagnosed HNC cases among the elderly is expected to increase by more than 60% by the year 2030 [5].

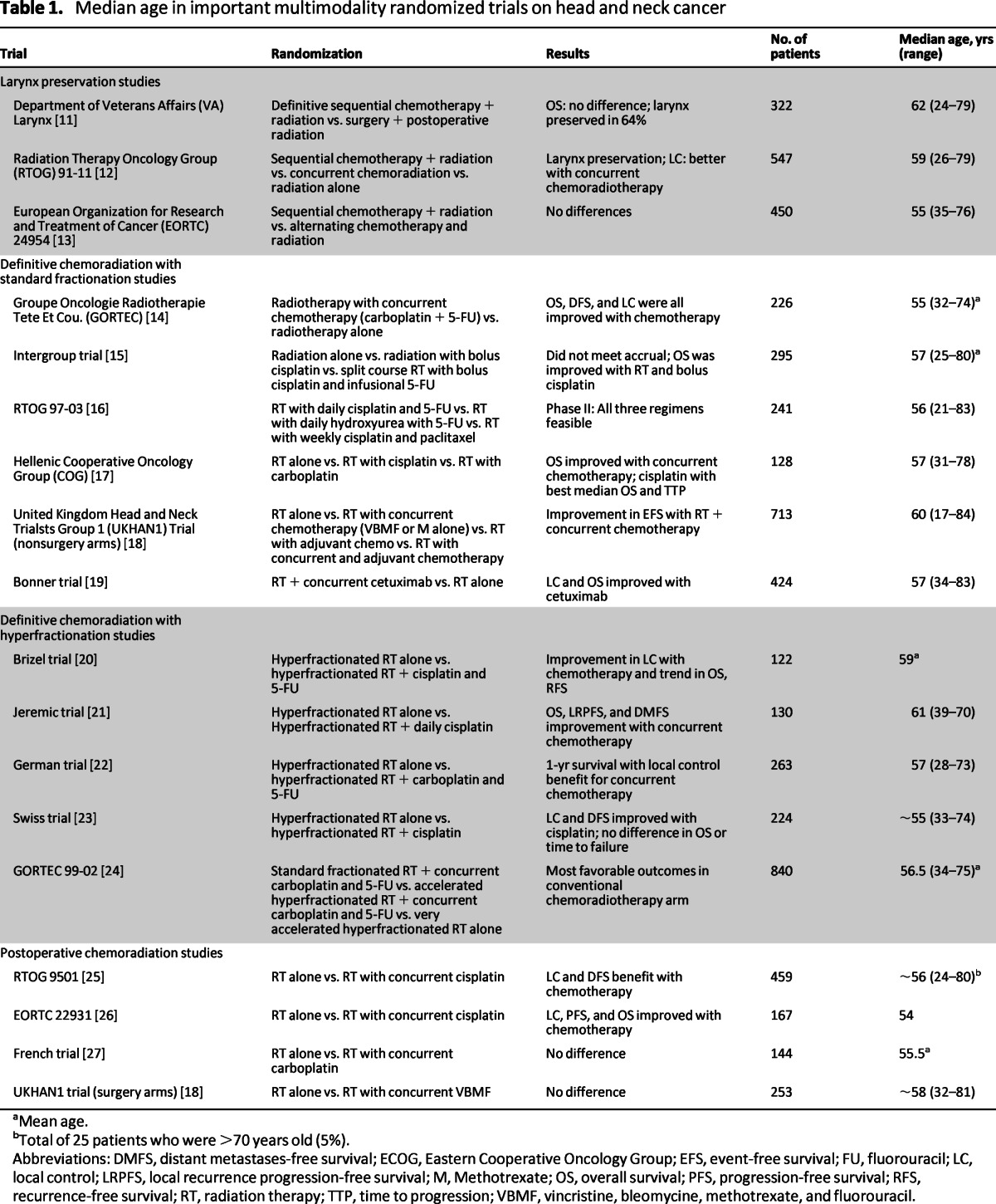

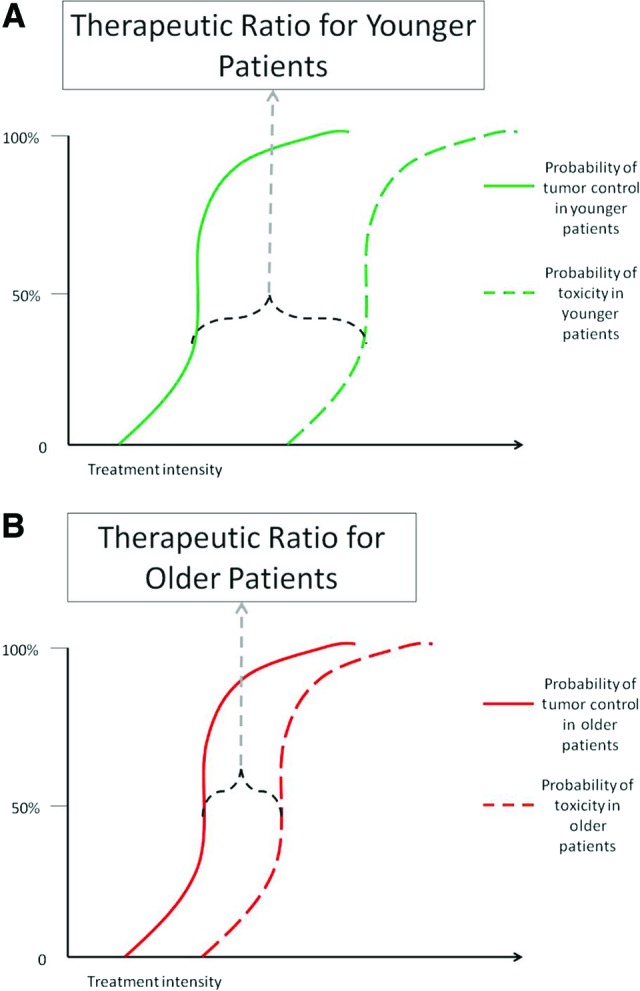

Treatment paradigms for older patients with HNC are not well defined. The majority of patients with HNC will present with advanced (stage III and IV) disease requiring multimodality therapy [6]. Combined surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy cause significant acute toxicity and long-term morbidity, thus reducing compliance to therapy, quality of life, and life expectancy. These morbidities can be profound in older patients, secondary to comorbid medical conditions and impaired functional status. Hence, older patients are often considered poor candidates for multimodality treatment and are subsequently less likely to receive standard of care therapy compared with younger patients [7, 8]. This bias against optimal treatment may jeopardize their chance of cure. In addition, older patients are often ineligible for the large prospective randomized trials on which treatment paradigms are based (Table 1) [9–27]. For example, in a recent meta-analysis of 93 clinical trials, only 692 of 17,346 patients (4%) were >70 years of age [28]. Thus, the outcomes of these trials may not be applicable to older patients. Despite recommendations not to include age limits in large prospective trials, many ongoing trials continue to have upper age limits in their inclusion criteria. For these reasons, many are concerned that older patients with HNC have a smaller therapeutic benefit with treatment intensification compared with their younger peers (Fig. 1) [29].

Table 1.

Median age in important multimodality randomized trials on head and neck cancer

aMean age.

bTotal of 25 patients who were >70 years old (5%).

Abbreviations: DMFS, distant metastases-free survival; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EFS, event-free survival; FU, fluorouracil; LC, local control; LRPFS, local recurrence progression-free survival; M, Methotrexate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RT, radiation therapy; TTP, time to progression; VBMF, vincristine, bleomycine, methotrexate, and fluorouracil.

Figure 1.

Theoretical therapeutic ratio for head and neck cancer treatment. (A): Younger patients. (B): Older patients.

The purpose of this paper is to review the published literature to attempt to answer the following questions with regard to HNC, with an objective to better equip oncologists to manage older patients with HNC:

Do older patients have worse survival rates?

Do older patients experience worse toxicities?

Should comorbidity influence treatment recommendations?

Do older patients have worse quality of life after treatment?

Do older patients require more supportive care during treatment?

Methods

For each subsection of this review, we performed a PubMed search using the terms “head and neck cancer,” “older” or “elderly,” and the topic of each subsection. Relevant prospective and retrospective studies published from 1980 to 2012 were included. Studies published in languages other than English or not involving human subjects were not reviewed. There was no definitive age cutoff used for defining older patients.

Results

Survival Rates

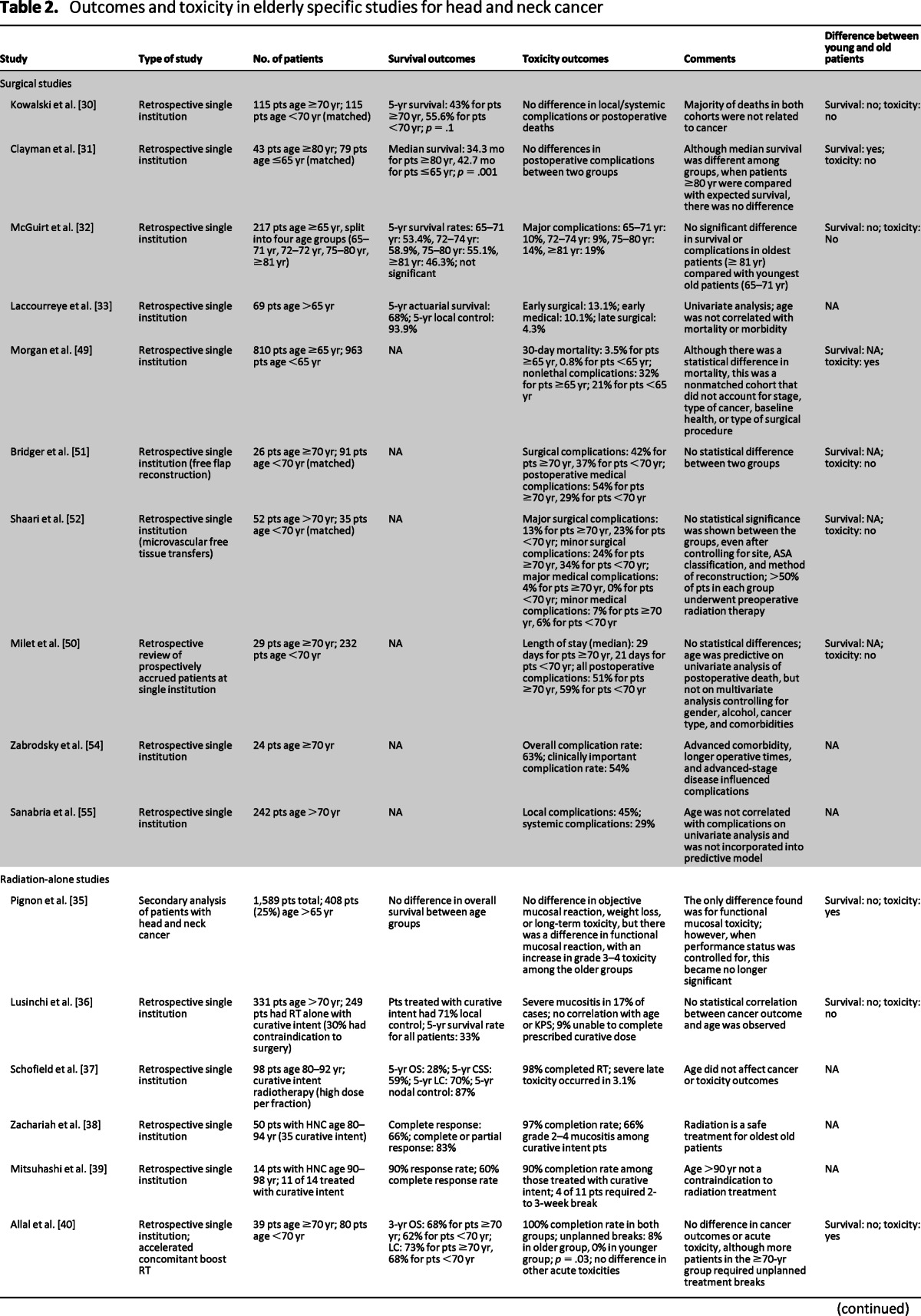

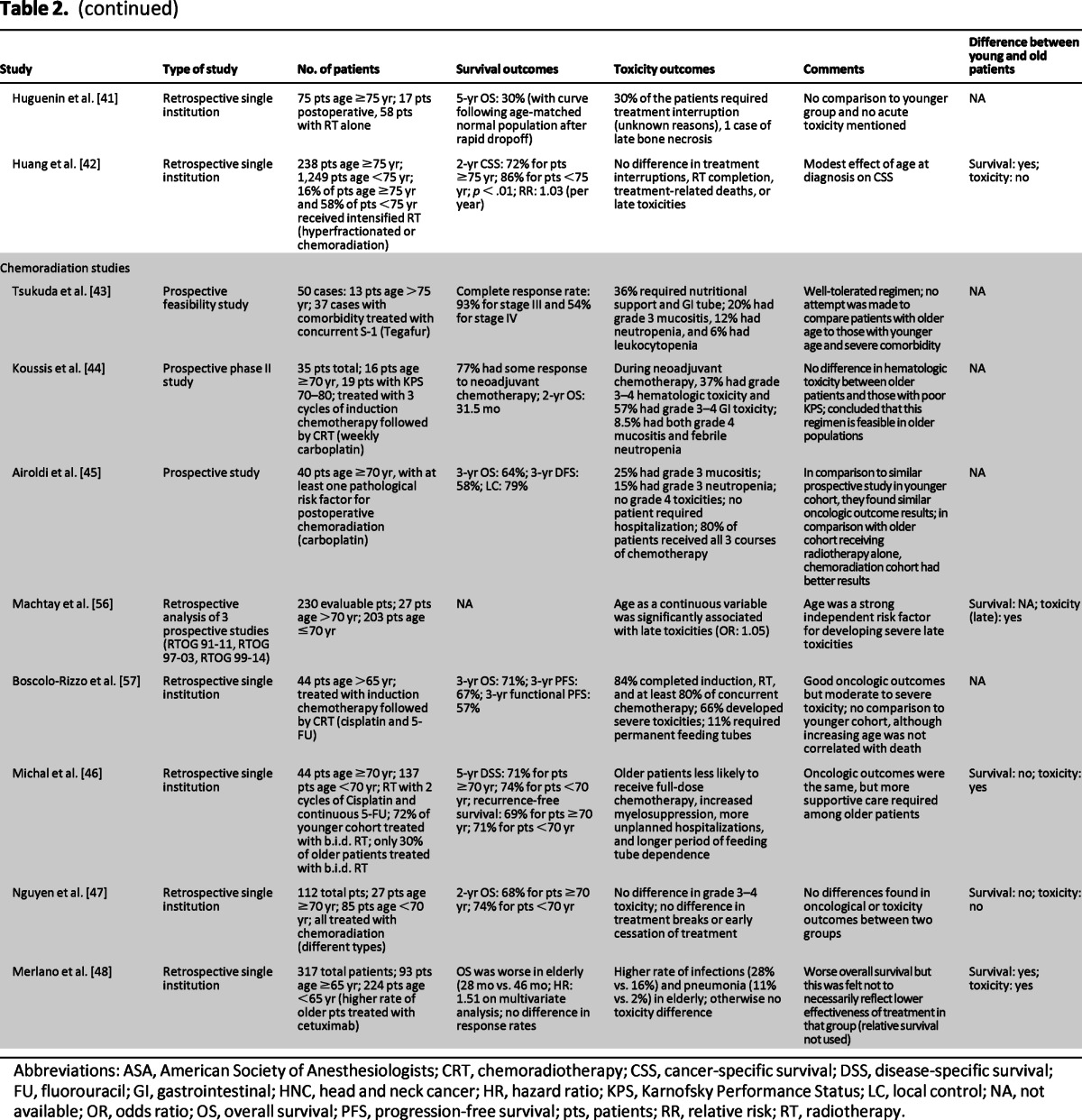

In the majority of studies comparing treatment modalities between older and younger cohorts with HNC, older patients did not appear to have worse survival than their younger peers. The data are summarized in Table 2 by modality and are discussed below.

Table 2.

Outcomes and toxicity in elderly specific studies for head and neck cancer

Table 2.

(continued)

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; CSS, cancer-specific survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; FU, fluorouracil; GI, gastrointestinal; HNC, head and neck cancer; HR, hazard ratio; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; LC, local control; NA, not available; OR, odds ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; pts, patients; RR, relative risk; RT, radiotherapy.

Surgery

Limited data suggest that selected older patients have survival outcomes similar to younger patients when treated primarily with surgery. In particular, a number of retrospective studies have matched older patients to a younger cohort and have shown no difference in survival outcome [30–32]. Kowalski et al. matched 115 patients who were ≥70 years of age by tumor type and stage to 115 patients <70 years of age and found no difference in 5-year survival rate [30]. In addition, multiple nonmatched retrospective studies have shown similar results [33, 34].

Radiation

Multiple retrospective single-institution studies all indicate that the oncologic outcomes among older patients receiving radiotherapy alone are similar to their younger cohorts [35–41]. However, only three studies directly compared outcomes among different age groups [35, 40, 42]. The first, a secondary analysis of four prospective European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer HNC trials, found no difference in overall survival among four different age groups, including patients >75 years [35]. The second study performed a comparison of 39 patients ≥70 years receiving accelerated concomitant boost radiation with 80 patients <70 years receiving the same radiation regimen [40]. There was no observed difference in 3-year overall survival or local control between the two groups. The third study showed that age, as a continuous variable, had a statistically significant detriment to cause specific survival; however, the effect was modest (relative risk: 1.03) [42].

Chemoradiation

Evidence suggests that older patients may not have a survival benefit from the addition of chemotherapy to radiation. In a meta-analysis of 93 clinical trials, Pignon et al. demonstrated that although there appeared to be an overall survival benefit of 4.5% at 5 years with the addition of chemotherapy, this benefit was not evident among older patients [28]. Specifically, patients age 71 and older had no statistical benefit in 5-year survival rates with the addition of chemotherapy. The authors suggest that this may be due to the increased rate of noncancer deaths among this cohort of older patients, but it may also be due to the small number of evaluable patients [28].

We identified three prospective studies that treated older patients with chemoradiotherapy to identify the tolerability of different chemoradiation regimens [43–45]. Although these studies showed relatively good short-term survival results, they did not study their regimens in younger cohorts and thus do not answer our question. Two retrospective studies directly compared older cohorts with their younger peers and suggested no difference in overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival, or recurrence-free survival among patients ≥70 years [46, 47]. However, an additional retrospective study suggests a statistically significant decrease in OS among patients ≥65 years [48]. It is important to note that it is difficult to compare outcomes among different studies because many of these studies used different chemotherapy regimens even within the same study. For example, Merlano et al. had a higher percentage of the older patients receiving cetuximab and radiation with a higher percentage of younger patients receiving platinum-based chemoradiation [48]. Therefore, although the existing data supports that older patients have oncologic outcomes to chemoradiation similar to younger patients, the quality of the data limits the confidence of this assertion.

Conclusion

Surgery, radiation, and chemoradiation appear to be equally efficacious in older and younger patients. Treatment recommendations should not be influenced by a perception that one modality may not be efficacious in older patients.

Toxicity

It stands to reason that patients with medical comorbidities and poorer functional reserve (common issues in older patients with HNC) would experience more and/or worse treatment-related toxicity. Treatment modality-specific toxicity is reviewed and summarized in Table 2. The results of these studies appear to be mixed in their conclusions.

Surgery

Two surgical retrospective series suggested an increased risk of postoperative mortality in older patients [49, 50]. Morgan et al. [49] observed an increase in 30-day mortality in older patients (3.5% mortality) as compared with that in a younger cohort (0.8%). This study did not match the cohorts by tumor, stage, comorbidity, or any other risk factors. The authors concluded that, given the relatively low rate of perioperative mortality, age alone should not be a contraindication to aggressive surgery. Milet et al. observed age to be associated with postoperative mortality on univariate but not multivariate analysis [50]. However, an additional six retrospective matched cohort reviews [30–32, 51–53] and three unmatched retrospective reviews [33, 54, 55] show no correlation between age alone and postoperative complications (Table 2).

Radiation

Two retrospective studies that compare older patients with younger patients suggest an increase in mucositis [35] and/or unplanned treatment breaks [40] among the older cohorts. However, other comparative studies appear to show no difference in acute toxicities or treatment interruptions [36, 42]. In their retrospective study comparing 238 patients ≥75 years to 1,249 patients <75 years, Huang et al. demonstrated no difference in treatment interruptions, radiotherapy completion, treatment-related deaths, or late toxicities [42]. In addition, three additional studies retrospectively analyzed their outcomes in their oldest patients (≥80 years) and demonstrated acceptable rates of toxicities [37–39].

Chemoradiation

As treatment intensity increases, the potential for greater toxicity also increases. In a retrospective analysis of three prospective Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) studies, Machtay et al. demonstrated that age as a continuous variable was significantly associated with developing severe late toxicities (odds ratio: 1.05, p = .001) [56]. Two retrospective studies that directly compared toxicity outcomes among older cohorts with those of younger cohorts demonstrated worse tolerability and toxicity to treatment. Specifically, they identified worse compliance with chemotherapy, more unplanned hospitalizations, increased myelosuppresion, increased infections/pneumonia rates, and longer periods of feeding tube dependence among the older cohorts [46, 48]. Additional noncomparative retrospective studies demonstrated high rates of severe toxicities among older cohorts [57].

Unfortunately, the three prospective trials that analyzed feasibility of multimodality treatment regimens in older patient populations do not directly answer our question of whether older patients experience worse toxicity. Although they all report relatively similar toxicity profiles to the larger randomized trials, including younger cohorts [43–45], they include highly selected patient populations and do not report all relevant toxicities. In particular, one study only reported toxicities during the induction portion of the treatment regimen [44].

Cisplatin is the standard chemotherapy to give concurrently with radiation. It is common practice to substitute cetuximab with cisplatin in older patients because of perceived lower toxicity profile as observed in the Bonner trial [19]. However, there are now multiple published retrospective studies that demonstrate either similar or increased rates of mucositis in patients who receive cetuximab compared with those who receive cisplatin concurrent with radiation [58, 59]. Additionally, a randomized trial undertaken by the Gruppo di Studio sui Tumori della Testa (GSTTC) Italian Study Group compared concurrent cetuximab radiation with concurrent cisplatin radiation with or without induction in a 2 × 2 design [60]. Preliminary toxicity results demonstrated similar rates of mucositis (76% with cetuximab vs. 78% with cisplatin; p = .63). More patients were able to complete concurrent cisplatin compared with cetuximab (93% vs. 81%; p < .01) without dose modifications (75% vs. 50%; p < .01). Furthermore, median duration of concurrent radiation was 1 week longer in the cetuximab arm (7 weeks cisplatin versus 8 weeks cetuximab; p < .01). Thus, concurrent cetuximab may not result in less acute toxicity [60].

Locally recurrent disease in the setting of previous radiation is a challenge in the older patient with HNC. Currently, adjuvant chemotherapy alone is considered standard of care [61]. Older patients in this setting have worse toxicity from platinum-based chemotherapy compared with their younger peers [62]. Prospective clinical trials have shown that reirradiation with chemotherapy in carefully selected patients results in poor survival rates and high rates of major toxicities. The RTOG has conducted two phase II trials evaluating the efficacy of reirradiation and chemotherapy: RTOG 9610 [63] and 9911 [64]. The median age of patients in these trials were 62 and 60 years. In RTOG 9610, the incidence of severe acute toxicity was 17.7% (grade 4) and 7.6% (grade 5) [63]. The 2-year overall survival estimate was 15.2% and the cumulative incidence of grade 3–4 late toxicity was 9.4% [63]. The follow-up phase II study RTOG 9911 (60 Gy with concurrent cisplatin and paclitaxel) had higher 2-year overall survival rate (25.9%) but comparable acute grade 4 or worse (28%) and grade 5 (8%) toxicities [64]. Late toxicities were also significant (34% grade 3–4, 4% grade 5) [64]. Local regional recurrences after radiotherapy can sometimes be salvaged with surgery. The efficacy of reirradiation with chemotherapy after salvage surgery has been evaluated in a randomized trial from France [65]. The median age of patients in this study was not reported. Patients were randomized to either salvage surgery alone versus salvage surgery and postoperative chemoradiotherapy. The addition of reirradiation with chemotherapy after salvage surgery improved disease-free survival but not overall survival rates. Furthermore, 39% of patients in the chemoradiation arm experienced grade 3–4 late toxicity (compared with 10% in the surgery-alone arm) [65]. In the above trials, highly selected patients (i.e., excellent performance status, minimal comorbidities) were enrolled; despite careful selection, outcomes were poor and severe toxicities were excessive. In older patients with HNC, it is likely that toxicities will be worse. Our practice is to avoid reirradiation whenever possible and advocate salvage surgery alone. Reirradiation is only attempted in the most carefully selected patients.

Conclusion

Older patients experience greater acute and late toxicity as the intensity of treatment increases. Specifically, the addition of chemotherapy to radiation increases toxicity and reduces tolerance to therapy. The belief that cetuximab (when given concurrently with radiation) is less toxic than cisplatin may not be true. Re-irradiation with/without concurrent chemotherapy in the recurrent/previously irradiated setting should be avoided.

Comorbidities and Treatment Recommendations

Patients with HNC often have a history of tobacco and alcohol use and multiple other chronic illnesses related to these habits. In a study of patients with laryngeal cancer, 65% of patients had some form of comorbid illness and 25% had multiple comorbidities [66]. In patients >70 years old, the incidence of comorbidities was as high as 75% [67]. There are multiple indices that measure comorbidity and attempt to grade the burden of particular comorbidities. Two of the most well-known indices are the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27 [68] and the Charlson Comorbidity Index [69].

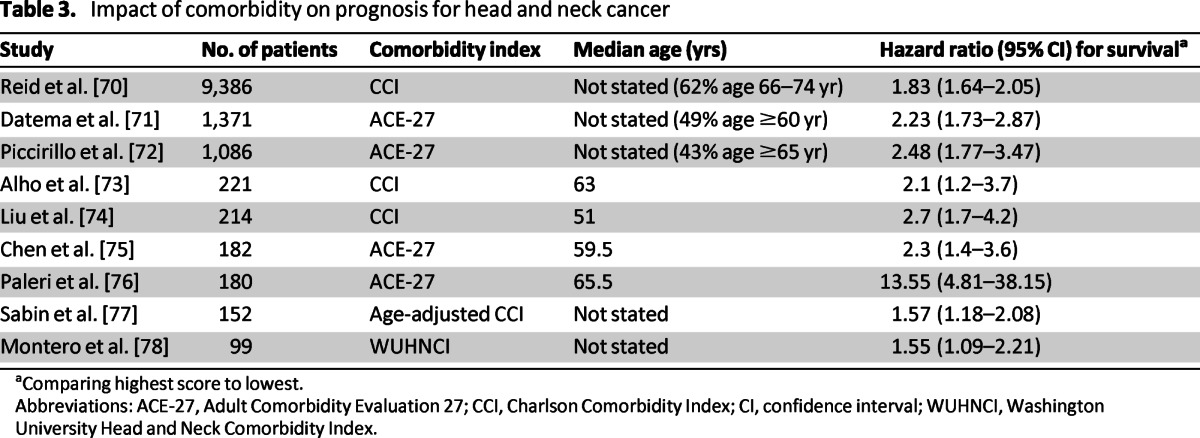

There are multiple articles establishing the relationship between comorbidity and prognosis for older patients with HNC (Table 3) [70–78]. The association between comorbidity and overall survival found in all of these articles is understandable. The greater the severity of the comorbidity, the more likely a patient is to die of disease unrelated to cancer. However, multiple studies have also demonstrated worse disease-specific survival rates or higher odds of disease recurrence among patients with worse comorbidity [72, 76, 79]. It is possible that deaths unrelated to cancer are being misattributed to cancer. Alternatively, patients with more comorbidities may receive less intensive treatment (i.e., physician recommendation or patient preference), leading to worse disease-related outcomes, or they may receive more intensive therapy then they can tolerate, leading to treatment alterations that result in less effective treatment. This may explain the results of the Pignon et al. [28] meta-analysis, which observed less benefit from intensive treatment in the elderly.

Table 3.

Impact of comorbidity on prognosis for head and neck cancer

aComparing highest score to lowest.

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; WUHNCI, Washington University Head and Neck Comorbidity Index.

Conclusion

Older patients with more comorbidities experience more treatment-related toxicity and poorer outcomes. Intensification of treatment (i.e., adding chemotherapy to radiation) should only be in carefully selected patients and done when absolutely necessary.

Quality of Life

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept that includes evaluation of positive and negative aspects of life [80]. Quality of life refers to “a patient's appraisal of and satisfaction with their current level of functioning compared with what they perceive to be possible or ideal” [81]. The subjective evaluation of patients' perceptions of their quality of life (as measured by validated questionnaires) may be especially challenging in older patients.

Limited data exists on the quality of life of older patients with any cancer. Many believe that older patients suffer more side effects and toxicities from treatment and therefore have more difficulty adjusting to their cancer diagnosis. However, at least one study has shown that physicians tend to overestimate the problems of their older patients with cancers.

Limited data exists on the quality of life of older patients with any cancer. Many believe that older patients suffer more side effects and toxicities from treatment and therefore have more difficulty adjusting to their cancer diagnosis. However, at least one study has shown that physicians tend to overestimate the problems of their older patients with cancers [82]. The same study indicated that it was younger patients who reported more quality-of-life difficulties through treatment. In a prospective study on 78 older patients and 105 younger patients with HNC undergoing surgery, Derks et al. demonstrated that although older patients had worse physical functioning prior to treatment, the difference remained constant throughout treatment, indicating that the older patients did not have a higher relative decrease in physical functioning compared with younger patients. In addition, they found that younger patients reported more pain at 6 months than older patients [83]. In a retrospective study of 638 patients, Laraway et al. demonstrated that patients older than 65 had better physical and emotional functioning 1 year after surgery than younger patients [84].

These findings may suggest that older patients experience less quality-of-life difficulties than their younger peers. Alternatively, they may suggest that older patients are less likely to report changes in quality of life due to differences in perceived expectations. A 45-year-old patient who missed a month of work due to posttreatment pain may score changes in quality of life worse than a retired 70-year-old patient with the same pain. Although the current data suggests that older patients do not have worse quality of life following treatment, the subjective nature of quality-of-life endpoints makes it difficult for clinicians to interpret this data for their individual older patients.

Conclusion

The available data suggest that patient-reported quality of life is not significantly reduced after treatment in older patients with HNC. However, we do not recommend using these data to inform patient counseling and treatment decisions.

Supportive Care During Treatment

HNC and its therapy are associated with marked symptom burden and functional impairment [85]. Supportive care is crucial to enable patients to complete their prescribed treatment course without breaks in treatment and to recover safely from toxicities. Although the term “palliative care” is often used interchangeably with “supportive care,” we use the term “supportive care” to mean care that helps patients and their families cope with cancer and its treatment [86].

A myriad of symptoms such as constipation, nausea/vomiting, pain, mucositis, and xerostomia affect those undergoing treatment for HNC. Each symptom can have a unique presentation and treatment in the older patient. There is sparse literature specific to the supportive care needs of older patients undergoing chemoradiation. Michal et al. [46] compared toxicities in patients older and younger than 70 years who were receiving concurrent chemoradiation. Patients older than 70 years required more supportive care, with 89% requiring feeding tube placement, as compared with 69% in the younger cohort. In a secondary analysis of five cross-sectional studies of patients with HNC, a statistical correlation between age and overall symptom burden and nutritional dysfunction during therapy was reported [85]. Although not specific to patients with HNC, in a prospective multicenter study, 53% of older adults experienced at least one grade 3–5 toxicity [88]. The authors correctly pointed out that even grade 2 toxicities, which were not looked at in this study, can dramatically affect the older patient. Grade 2 diarrhea, for example, could be enough to compromise an older patient's volume and electrolyte status, whereas the younger patient could more easily compensate.

The use of prophylactic feeding tubes for patients with HNC is controversial. Many argue that prophylactic placements helps avoid significant weight loss and dehydration compared with placement of tubes if/when needed (therapeutic feeding tubes). Others argue that early placement of feeding tubes leads to atrophy of the swallowing mechanism and slower regain of swallowing function after treatment. The data are insufficient to draw definitive conclusions [89]. However, it has been the authors' clinical experience that when older patients require therapeutic feeding tubes, they are often not able to get them in enough time to avoid treatment delay, hospitalizations, or significant weight loss. Therefore, it has been the practice of the authors to place prophylactic feeding tubes in older patients receiving intensive curative chemoradiation.

The clinician must also be astute to physiologic changes that influence the older person's presentation of pain. Pain perception declines with age, is influenced by comorbidities and polypharmacy, and is altered with cognitive impairment or age-related impairments, such as hearing loss [90]. Particularly for the cognitively impaired, more time for evaluation is needed to facilitate adequate evaluation of symptoms.

Conclusion

Older patients with HNC require more supportive care. We recommend prophylactic feeding tubes. We also recommend coordinating care with the patient's other general practitioners and specialists. Specifically, we recommend increased interval of follow-up with patients' other physicians during cancer treatment. Efforts should be made by the oncologist to communicate regularly with other providers.

Discussion

Older patients with HNC may be different from their younger peers. It is generally accepted that age is a poor prognostic factor in the development of HNC [91]. One theory that partially explains the increasing incidence of cancer in the elderly is the prolonged exposure to environmental factors such as tobacco or alcohol in the setting of immunosenescence [92]. This differential in exposures and immunosenescence may lead to biological differences in the solid tumors that develop in older patients compared with their younger peers [93]. These biological differences could lead to differences in the way tumors respond to antineoplastic therapy, possibly leading to worse survival [94]. However, in our comprehensive review of the literature, we found no definitive indication that older patients have worse survival.

The retrospective nature of many of the studies reviewed makes it to difficult to interpret and integrate the findings of these studies. For example, the radiation studies differ from the surgical series in their patient populations. The radiation series included both older [39] and less healthy patients [36]; therefore, the survival outcomes cannot be directly compared with the surgical series. The radiation studies are also hard to compare because they include different patient ages, different tumor sites, and different radiation and chemotherapy regimens. For example, in one study, as many as 16% of the older patients received hyperfractionated (twice a day) treatment [42]. Our review of the literature on toxicity among older patients was also mixed. Many studies had different definitions of acute toxicity or may not have recorded toxicity well. We also have no indication if older patients required increased supportive care during their treatment compared with younger patients. This increased supportive care, if received, may be what allowed older patients to tolerate this often-morbid treatment.

With current treatment modalities, older patients with HNC do not have worse survival rates but may experience higher treatment-related toxicities than their younger peers, specifically as the intensity of treatment increases. Furthermore, comorbidities and functional age are better predictors of treatment tolerance and development of toxicities compared with chronological age.

To balance the risks and benefits of more effective or toxic treatment among older patients with comorbidities, we require better tools to help predict which patients will tolerate aggressive therapy. There is great interest among geriatric oncologists in the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) as a tool to assess functional age and health of older patients. The CGA is a series of tools and questionnaires used by clinicians to evaluate an older person's functional status, comorbidities, cognition, psychological status, social functioning and support, nutritional status, and medications [95]. Decreases in functional status based on poor scores in activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living on CGAs have been shown to predict for increased toxicities to both chemotherapy [88] and surgery [96] and predict for changes in planned treatment regimen [97]. To our knowledge, there are no published prospective studies on the use of the CGA for patients with HNC or patients receiving radiation therapy. However, studies have suggested that the CGA can be used as a tool to help choose appropriate therapy for individual patients [91, 98].

Better data are needed to answer the question of whether the benefits of intensive therapy truly outweigh the potential risks in selected older patients with HNC. Further, older patients are heterogeneous both in their disease and in their physiologic ability to tolerate therapy. Thus, prospective studies of older patients are needed to define which older patients are likely to tolerate intensive chemoradiotherapy. Pending better data, physicians should counsel older patients, incorporating prognosis of disease and the risks of treatment.

Future research should be directed at developing specific programs for supporting older patients throughout their treatment. These programs should be aimed at decreasing hospitalizations and emergency room visits, reducing treatment breaks or incomplete treatments, and providing better symptom management and satisfaction with treatment. These include assessing how objective measures of independence (e.g., activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living) or social support requirements change over different treatments.

Conclusions

Choosing therapy and caring for older patients with HNC is challenging. It is common practice to extrapolate results from clinical trials with few older patients to guide treatment. Evidence suggests that the therapeutic index may shrink as treatment intensity increases. With current treatment modalities, older patients with HNC do not have worse survival rates but may experience higher treatment-related toxicities than their younger peers, specifically as the intensity of treatment increases. Furthermore, comorbidities and functional age are better predictors of treatment tolerance and development of toxicities compared with chronological age. Older patients require careful multidisciplinary assessment for the need for supportive care (e.g., prophylactic feeding tubes) to ensure successful completion of treatment. Ongoing studies exploring the value of geriatric assessments in older patients with HNC may allow clinicians to better choose treatment regimens and address toxicities during treatment. These tools may allow clinicians to better triage older patients with HNC for intensive multimodality treatment.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hyman Muss and the entire Geriatric Oncology Working Group at the University of North Carolina.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Noam A. VanderWalde, Mary E. Fleming, Jared Weiss, Bhishamjit S. Chera

Provision of study material or patients: Noam A. VanderWalde, Mary E. Fleming, Bhishamjit S. Chera

Collection and/or assembly of data: Noam A. VanderWalde, Mary E. Fleming, Bhishamjit S. Chera

Data analysis and interpretation: Noam A. VanderWalde, Mary E. Fleming, Jared Weiss, Bhishamjit S. Chera

Manuscript writing: Noam A. VanderWalde, Mary E. Fleming, Jared Weiss, Bhishamjit S. Chera

Final approval of manuscript: Noam A. VanderWalde, Mary E. Fleming, Jared Weiss, Bhishamjit S. Chera

Disclosures

Jared Weiss: Celgene (C/A); GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Astellas, Acceleron (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section editors: Arti Hurria: GTX, Seattle Genetics (C/A); Celgene (previously Abraxis Bioscience), GSK (RF); Matti Aapro: Sanofi (C/A)

Reviewer “A”: None

Reviewer “B”: None

C/A: Consulting/advisory relationship; RF: Research funding; E: Employment; H: Honoraria received; OI: Ownership interests; IP: Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; SAB: scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SC, Carpenter WR, Tyree S, et al. Increasing incidence of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in young white women, age 18 to 44 years. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1488–1494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. [Accessed April 30, 2011]. Available at http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 5.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argiris A, Eng C. Epidemiology, staging, and screening of head and neck cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2003;114:15–60. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48060-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Rijke JM, Schouten LJ, Schouten HC, et al. Age-specific differences in the diagnostics and treatment of cancer patients aged 50 years and older in the province of Limburg, The Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:677–685. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fentiman IS, Tirelli U, Monfardini S, et al. Cancer in the elderly: Why so badly treated? Lancet. 1990;335:1020–1022. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91075-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: A 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4626–4631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefebvre JL, Rolland F, Tesselaar M, et al. Phase 3 randomized trial on larynx preservation comparing sequential vs alternating chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:142–152. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:2081–2086. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.24.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:92–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garden AS, Harris J, Vokes EE, et al. Preliminary results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 97–03: A randomized phase ii trial of concurrent radiation and chemotherapy for advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2856–2864. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountzilas G, Ciuleanu E, Dafni U, et al. Concomitant radiochemotherapy vs radiotherapy alone in patients with head and neck cancer: A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group Phase III Study. Med Oncol. 2004;21:95–107. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:2:095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobias JS, Monson K, Gupta N, et al. Chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer: 10-year follow-up of the UK Head and Neck (UKHAN1) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:66–74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70306-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, et al. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1798–1804. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806183382503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Milicic B, et al. Hyperfractionated radiation therapy with or without concurrent low-dose daily cisplatin in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1458–1464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staar S, Rudat V, Stuetzer H, et al. Intensified hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy limits the additional benefit of simultaneous chemotherapy: Results of a multicentric randomized German trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huguenin P, Beer KT, Allal A, et al. Concomitant cisplatin significantly improves locoregional control in advanced head and neck cancers treated with hyperfractionated radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4665–4673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourhis J, Sire C, Graff P, et al. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy versus acceleration of radiotherapy with or without concomitant chemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck carcinoma (GORTEC 99–02): An open-label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:145–153. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Racadot S, Mercier M, Dussart S, et al. Randomized clinical trial of post-operative radiotherapy versus concomitant carboplatin and radiotherapy for head and neck cancers with lymph node involvement. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pignon JP, le Maitre A, Maillard E, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): An update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanderWalde N, Meyer AM, Tyree SD, et al. Patterns of care in elderly patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A SEER-Medicare analysis. ASCO meeting abstracts. J Clin Oncol. 2012 May 30;(suppl) abstr 5539) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kowalski LP, Alcantara PS, Magrin J, et al. A case-control study on complications and survival in elderly patients undergoing major head and neck surgery. Am J Surg. 1994;168:485–490. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayman GL, Eicher SA, Sicard MW, et al. Surgical outcomes in head and neck cancer patients 80 years of age and older. Head Neck. 1998;20:216–223. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199805)20:3<216::aid-hed6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGuirt WF, Davis SP., 3rd Demographic portrayal and outcome analysis of head and neck cancer surgery in the elderly. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:150–154. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890020014004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laccourreye O, Brasnu D, Perie S, et al. Supracricoid partial laryngectomies in the elderly: Mortality, complications, and functional outcome. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:237–242. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199802000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barzan L, Veronesi A, Caruso G, et al. Head and neck cancer and ageing: A retrospective study in 438 patients. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:634–640. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100113453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pignon T, Horiot JC, Van den Bogaert W, et al. No age limit for radical radiotherapy in head and neck tumours. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2075–2081. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lusinchi A, Bourhis J, Wibault P, et al. Radiation therapy for head and neck cancers in the elderly. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;18:819–823. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90403-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schofield CP, Sykes AJ, Slevin NJ, et al. Radiotherapy for head and neck cancer in elderly patients. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(03)00249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zachariah B, Balducci L, Venkattaramanabalaji GV, et al. Radiotherapy for cancer patients aged 80 and older: A study of effectiveness and side effects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:1125–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitsuhashi N, Hayakawa K, Yamakawa M, et al. Cancer in patients aged 90 years or older: Radiation therapy. Radiology. 1999;211:829–833. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.3.r99jn21829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allal AS, Maire D, Becker M, et al. Feasibility and early results of accelerated radiotherapy for head and neck carcinoma in the elderly. Cancer. 2000;88:648–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huguenin P, Sauer M, Glanzmann C, et al. Radiotherapy for carcinomas of the head and neck in elderly patients. Strahlenther Onkol. 1996;172:485–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang SH, O'Sullivan B, Waldron J, et al. Patterns of care in elderly head-and-neck cancer radiation oncology patients: A single-center cohort study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsukuda M, Ishitoya J, Mikami Y, et al. Analysis of feasibility and toxicity of concurrent chemoradiotherapy with S-1 for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in elderly cases and/or cases with comorbidity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:945–952. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0946-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koussis H, Scola A, Bergamo F, et al. Neoadjuvant carboplatin and vinorelbine followed by chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck or oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A phase II study in elderly patients or patients with poor performance status. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1383–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Airoldi M, Cortesina G, Giordano C, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in older patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michal SA, Adelstein DJ, Rybicki LA, et al. Multi-agent concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer in the elderly. Head Neck. 2012;34:1147–1152. doi: 10.1002/hed.21891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen NP, Vock J, Chi A, et al. Impact of intensity-modulated and image-guided radiotherapy on elderly patients undergoing chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merlano MC, Monteverde M, Colantonio I, et al. Impact of age on acute toxicity induced by bio- or chemo-radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan RF, Hirata RM, Jaques DA, et al. Head and neck surgery in the aged. Am J Surg. 1982;144:449–451. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milet PR, Mallet Y, El Bedoui S, et al. Head and neck cancer surgery in the elderly–Does age influence the postoperative course? Oral Oncol. 2010;46:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bridger AG, O'Brien CJ, Lee KK. Advanced patient age should not preclude the use of free-flap reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Am J Surg. 1994;168:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaari CM, Buchbinder D, Costantino PD, et al. Complications of microvascular head and neck surgery in the elderly. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:407–411. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sesterhenn AM, Schotte TL, Bauhofer A, et al. Head and neck cancer surgery in the elderly: Outcome evaluation with the McPeek score. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:110–115. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zabrodsky M, Calabrese L, Tosoni A, et al. Major surgery in elderly head and neck cancer patients: Immediate and long-term surgical results and complication rates. Surg Oncol. 2004;13:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanabria A, Carvalho AL, Melo RL, et al. Predictive factors for complications in elderly patients who underwent head and neck oncologic surgery. Head Neck. 2008;30:170–177. doi: 10.1002/hed.20671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A, et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: An RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3582–3589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Muzzi E, Trabalzini F, et al. Functional organ preservation after chemoradiotherapy in elderly patients with loco-regionally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:1349–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1489-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koutcher L, Sherman E, Fury M, et al. Concurrent cisplatin and radiation versus cetuximab and radiation for locally advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:915–922. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh L, Gillham C, Dunne M, et al. Toxicity of cetuximab versus cisplatin concurrent with radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer (LAHNSCC) Radiother Oncol. 2011;98:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghi MG, Paccagnella A, Ferrari D, et al. Cetuximab/radiotherapy (CET+RT) versus concomitant chemoradiotherapy (cCHT+RT) with or without induction docetaxel/cisplatin/5-fluorouracil (TPF) in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LASCCHN): Preliminary results on toxicity of a randomized, 2x2 factorial, phase II-III study ( NCT01086826) J Clin Oncol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong SJ, Machtay M, Li Y. Locally recurrent, previously irradiated head and neck cancer: Concurrent re-irradiation and chemotherapy, or chemotherapy alone? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2653–2658. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Argiris A, Li Y, Murphy BA, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:262–268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spencer SA, Harris J, Wheeler RH, et al. Final report of RTOG 9610, a multi-institutional trial of reirradiation and chemotherapy for unresectable recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2008;30:281–288. doi: 10.1002/hed.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langer CJ, Harris J, Horwitz EM, et al. Phase II study of low-dose paclitaxel and cisplatin in combination with split-course concomitant twice-daily reirradiation in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 9911. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4800–4805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janot F, de Raucourt D, Benhamou E, et al. Randomized trial of postoperative reirradiation combined with chemotherapy after salvage surgery compared with salvage surgery alone in head and neck carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5518–5523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paleri V, Narayan R, Wight RG. Descriptive study of the type and severity of decompensation caused by comorbidity in a population of patients with laryngeal squamous cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:517–521. doi: 10.1258/0022215041615281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanabria A, Carvalho AL, Vartanian JG, et al. Comorbidity is a prognostic factor in elderly patients with head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1449–1457. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27. Piccirillo JF, Costas I, Claybour P, et al. The measurement of comorbidity by cancer registries. J Registry Manage. 2003;30:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Charlson Comorbidity Index. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reid BC, Alberg AJ, Klassen AC, et al. Comorbidity and survival of elderly head and neck carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2001;92:2109–2116. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2109::aid-cncr1552>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Datema FR, Ferrier MB, van der Schroeff MP, Baatenburg de Jong RJ. Impact of comorbidity on short-term mortality and overall survival of head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2010;32:728–736. doi: 10.1002/hed.21245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, et al. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alho OP, Hannula K, Luokkala A, et al. Differential prognostic impact of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2007;29:913–918. doi: 10.1002/hed.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu CT, Chiu TJ, Huang TL, et al. Impact of comorbidity on survival for locally advanced head and neck cancer patients treated by radiotherapy or radiotherapy plus chemotherapy. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen AY, Matson LK, Roberts D, et al. The significance of comorbidity in advanced laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2001;23:566–572. doi: 10.1002/hed.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paleri V, Wight RG, Davies GR. Impact of comorbidity on the outcome of laryngeal squamous cancer. Head Neck. 2003;25:1019–1026. doi: 10.1002/hed.10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sabin SL, Rosenfeld RM, Sundaram K, et al. The impact of comorbidity and age on survival with laryngeal cancer. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:578, 581–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Montero EH, Trufero JM, Romeo JA, et al. Comorbidity and prognosis in advanced hypopharyngeal-laryngeal cancer under combined therapy. Tumori. 2008;94:24–29. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paleri V, Wight RG, Silver CE, et al. Comorbidity in head and neck cancer: A critical appraisal and recommendations for practice. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cella DF, Cherin EA. Quality of life during and after cancer treatment. Compr Ther. 1988;14:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kahn SB, Houts PS, Harding SP. Quality of life and patients with cancer: A comparative study of patient versus physician perceptions and its implications for cancer education. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7:241–249. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Derks W, de Leeuw RJ, Hordijk GJ, et al. Quality of life in elderly patients with head and neck cancer one year after diagnosis. Head Neck. 2004;26:1045–1052. doi: 10.1002/hed.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laraway DC, Lakshmiah R, Lowe D, et al. Quality of life in older people with oral cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murphy BA. Advances in quality of life and symptom management for head and neck cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:242–247. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32832a230c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferrell B, Paice J, Koczywas M. New standards and implications for improving the quality of supportive oncology practice. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3824–3831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bond SM, Dietrich MS, Murphy BA. Association of age and symptom burden in patients with head and neck cancer. ORL Head Neck Nurs. 2011;29:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Orphanidou C, Biggs K, Johnston ME, et al. Prophylactic feeding tubes for patients with locally advanced head-and-neck cancer undergoing combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy-systematic review and recommendations for clinical practice. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:e191–e201. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Balducci L, Carreca I. Supportive care of the older cancer patient. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48:S65–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Syrigos KN, Karachalios D, Karapanagiotou EM, et al. Head and neck cancer in the elderly: An overview on the treatment modalities. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Balducci L, Lyman GH, Ershler WB, et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Oncology. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Piantanelli L. Cancer and aging: From the kinetics of biological parameters to the kinetics of cancer incidence and mortality. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;521:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb35268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zbar AP, Gravitz A, Audisio RA. Principles of surgical oncology in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:51–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: Recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Audisio RA, Pope D, Ramesh HS, et al. Shall we operate? Preoperative assessment in elderly cancer patients (PACE) can help. A SIOG surgical task force prospective study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Caillet P, Canoui-Poitrine F, Vouriot J, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in the decision-making process in elderly patients with cancer: ELCAPA study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3636–3642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ortholan C, Benezery K, Dassonville O, et al. A specific approach for elderly patients with head and neck cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22:647–655. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328344282a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]