Abstract

Background

Evidence for superior outcome by adhering to therapy guidelines is imperative to their acceptance and adaptation for the optimal management of disease variants.

Objective

Comparative study of prospective outcomes in simultaneous consideration of independent variables in groups of 150 patients of plaque psoriasis either treated adhering to or in digression of standard guidelines.

Methods

The psoriasis area severity index (PASI) and the dermatology life quality index (DLQI), prior to and after three months of uninterrupted therapy were examined in treatment groups among 150 patients. Recovery rates of 75% or more in PASI were compared. Independent variables were also examined for their bearing on the outcome.

Results

The vast majority was early onset disease phenotype. All three treatment regimens when administered in adherence to the guidelines yielded significantly superior rates of defined recovery both in PASI and DLQI. Compromise of the therapeutic outcome appeared in high stress profiles, obesity, female sex and alcohol, tobacco or smoking habit.

Conclusion

Conventional drug therapy of plaque psoriasis yields superior outcome by adhering to the consensus guidelines. Psychiatric address to stress must be integral and special considerations for phenotypic/syndromic variants is emphasized for effective therapy of psoriasis.

Keywords: Comparative effectiveness study, DLQI, PASI, Psoriasis, Therapeutic guidelines

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacoepidemiologic investigation of therapy effectiveness can provide pharmacogenomic clues. Potential predictors of response to therapy may be indicated from such studies, which is vital to conceiving individualized approaches to treatment1. Prospective recording of the objective response to treatment in suitably defined patient subsets administered similar treatment and assessment is a prudent approach to advancing the pharmacogenomic understanding of psoriasis2. Factors capable of aggravating autoimmunity are abnormally expressed in psoriasis, and there is variant susceptibility both of the major histocompatibility complex and T lymphocyte responses3. Psoriasis diagnosis relies on clinical criteria due to the non-availability of any valid markers. Clinical manifestations, disease course and response to therapies are very heterogenous in patients of psoriasis, possibly indicative of differences in molecular mechanisms. The association of specific co-morbidities is also increasingly appreciated. Interaction of complex genetic and environmental factor networks is believed to cause overt disease. Foreign antigen dependent mechanisms activating keratinocytes or misdirecting the immune response to dermal autoantigens, is considered trigger the pathogenesis. Non-immune contribution to immune processes also adds complexity to understanding. The altered expression of over 1,300 genes is detected in psoriatic lesions, programming for inflammation and phenotypic change in keratinocytes4. Epigenetic mechanisms altering biomolecules and influencing environmental triggers of pathogenesis are also said to be significant in chronic disease and neoplasia.

Individual health and trait, pharmacotoxicologic profiles of drugs and above all pathogenic mechanisms, are fundamental to comprehend for rational therapeutic address. Uncertainty of success, sustainability and failures of conventional psoriasis therapies reveals an oversimplified rationale, largely palliative intent and continued scope for improvement. Newer biological therapies attempt to intervene at specific steps of understood pathophysiology. The current interest is more on treatment that will be very effective in a particular disease profile, instead of those for all psoriasis cases with inconsistent outcomes and toxicity5. Consensus therapy guidelines incorporate opinions from numerous experts into simple generalizations toward standard care delivery in global perspective. Psoriasis with variegated pathology, merits continued re-examination of effectiveness regarding consensus guidelines in diverse patient populations, toward their refinement and evolution. New scientific knowledge may be incorporated through such very endeavors.

The present study focuses on the most prevalent and relatively stable form, plaque psoriasis. Strata of 150 patients based on the extent of body surface afflicted were studied for response to therapy. Therapeutic outcome was measured by the reduction of the psoriasis area severity index (PASI)6. Reference was made to consensus guidelines for psoriasis therapy7,8. After three months of uninterrupted treatment (without reasons to stop), outcomes were compared in patient groups where the therapeutic decision matched the directives of consensus guidelines with that in patients treated in digression from the guidelines. The responses to therapy were also preliminarily analyzed for the influence of independent traits regarding age, sex, body mass index (BMI), etc. An attempt is made to critically appraise therapeutic needs for specific apparent sets of patients toward optimal outcomes from inferences of observations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred ninty-two patients with plaque psoriasis of either sex and any age attending the Dermatology outpatient clinic, Sir Sunderlal Hospital Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India, were enrolled in the three month observational study. This study is duly approved by institutional review board and the approval number is dean/2008-09/38.

Forty-two of the enrolled patients were excluded through the course of study on notice of frequent noncompliance to therapeutic instructions and/or failure to report in a timely manner for review. The diagnosis of plaque psoriasis was made clinically by the dermatologist. Clinical criteria for diagnosis were the presence of erythematous papular lesions with adherent silvery white scales. Auspitz's sign was demonstrated in all the cases9. Relevant personal, disease related and health related history was sought in all cases. Demographic information was also collected.

Direct interaction with patients was adopted for assessment of disease and monitoring of prescribed drug therapy. Cases of plaque psoriasis who had not received any treatment in the past 4 weeks were included in study. The nature of study and its objective were explained and written consent was obtained from the patients, with assurance of not revealing identity. Severity of the presenting disease was determined by calculating the percentage of the involved body surface area (BSA)10,11. Location of the lesions was recorded and PASI score calculations were done6.

The 'Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)'12 was also elicited to evaluate the overall disease impact on quality of life.

Patients receiving no other treatment except for psoriasis were included in the study. The prescribed treatment regimen was analyzed for consistence or otherwise with prescription guidance for the given severity as per Callen et al.7 After three months of therapy the patient's condition was reassessed in a follow up session. The PASI score and DLQI score were again determined to calculate therapeutic outcomes for both clinical and in regard to quality of life regarding each drug regimen. A 75% improvement in the PASI score was considered as good response13 at the 3 month follow up.

The cases were categorized into two groups, i.e. those prescribed according to the guideline and others who were not prescribed as per the guideline. The rates of achievers of 75% improvement in the PASI score were used for comparison.

The terms mild, moderate and severe psoriasis are used subsequent to employed treatment regimens-

Less than 5% of body surface area involvement is considered as mild disease.

5~10% of body surface area involvement is considered as moderate disease.

More than 10% of body surface area involvement is considered as severe disease.

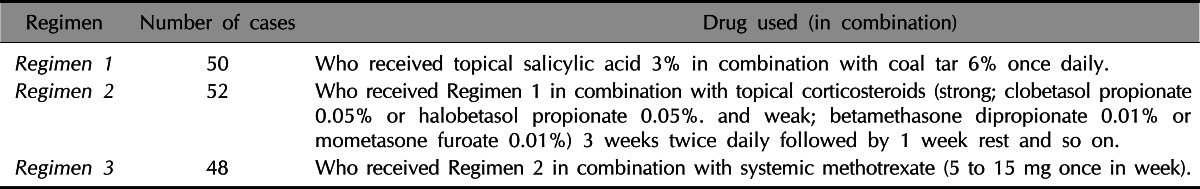

Mild, moderate and severe categories were considered treated as per the guidelines when the following regimens 1, 2 and 3 were prescribed, respectively:

Statistical analysis of differences between individual treatment groups was done for good and bad responder rates using moods median test and Fisher's exact-test for actual values. A difference was considered as statistically significant with p<0.05. For easy perception, percentage of cases achieving 75% or more recovery in PASI in respective groups, are presented in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Regimens prescribed in psoriasis cases

RESULTS

Among patients enrolled as per the inclusion criteria, 98 were males and 52 were females roughly giving a proportion of 2:1. Peak incidence in males was in the 31 to 40 year range, while in females it was 11 to 30 years. Mild and moderate disease involved extremities and scalp most often, while a further increase of severity led to involvement of the trunk. Other areas were less frequently involved.

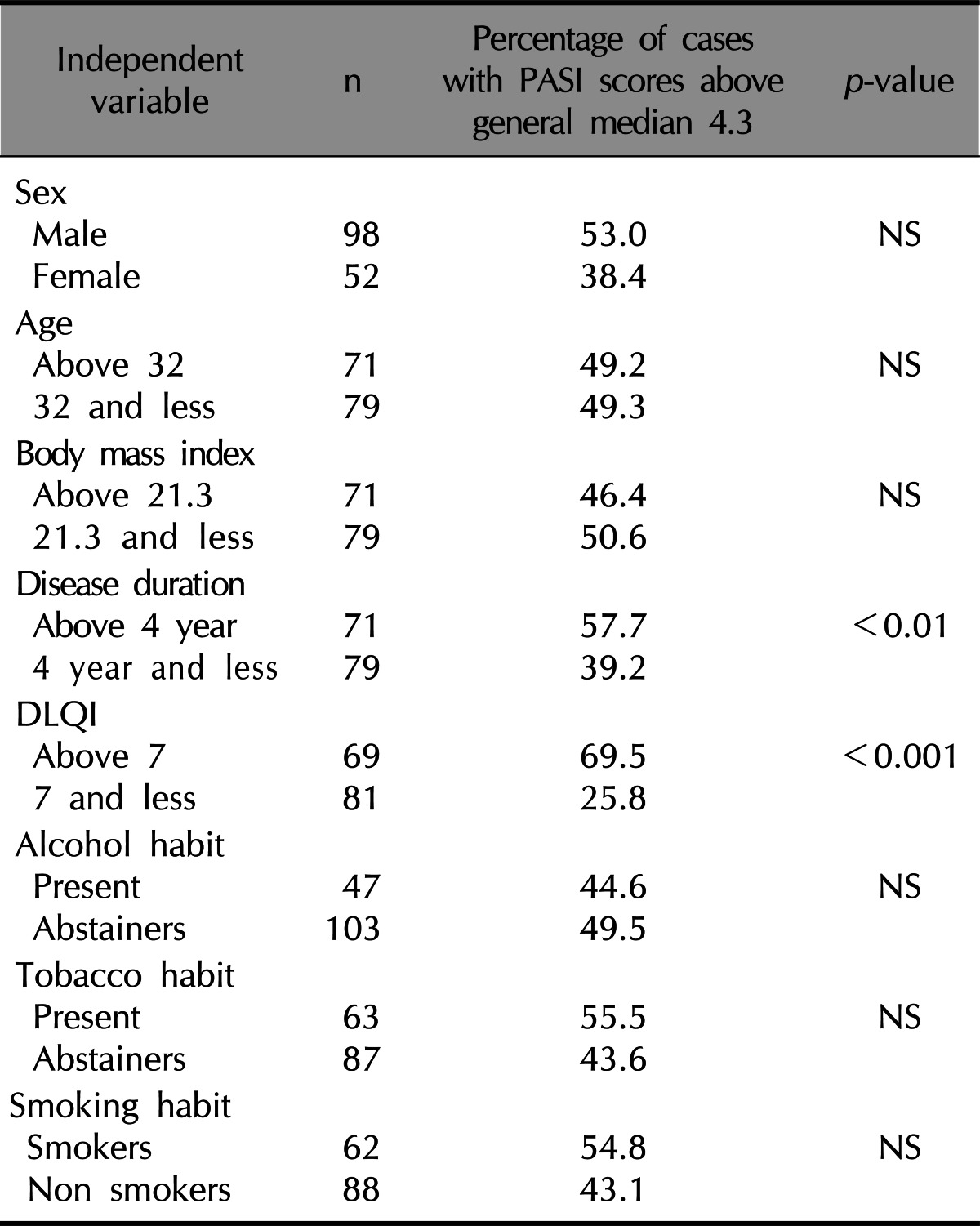

Independent variables sex, age, BMI or alcohol, tobacco and smoking habits were not associated with significantly higher baseline PASI score. The longer duration of disease and worse quality of life show significant association with high PASI scores at presentation in patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of independent variables to baseline PASI severity of plaque psoriasis

PASI: psoriasis area severity index, DLQI: dermatology life quality index, NS: non significant.

The following digressions from guidelines were encountered:

Use of regimen 1 even in cases exceeding 5% BSA involvement-constituting undertreatment

Use of regimen 2 even in cases not exceeding 5% BSA involvement-constituting overtreatment

Use of regimen 3 even in cases not exceeding 10% BSA involvement-constituting overtreatment

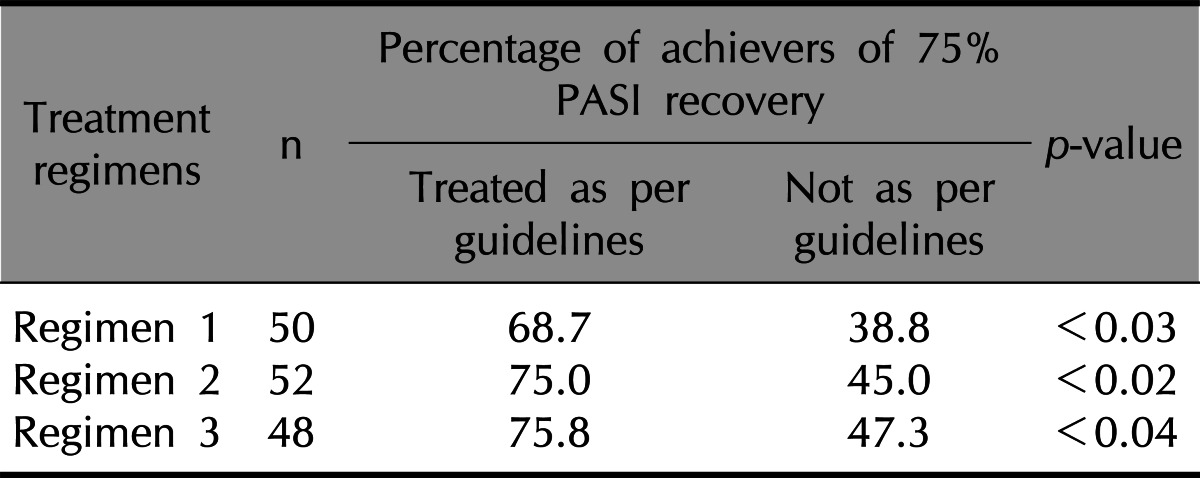

Adherence to guidelines significantly increased clinical outcome irrespective of baseline PASI scores, digression of guidelines resulted in a significantly greater reduction of outcome in patients with high PASI scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of cases attaining 75% or higher recovery in PASI in those treated adhering or digressing guidelines under different regimens

PASI: psoriasis area severity index.

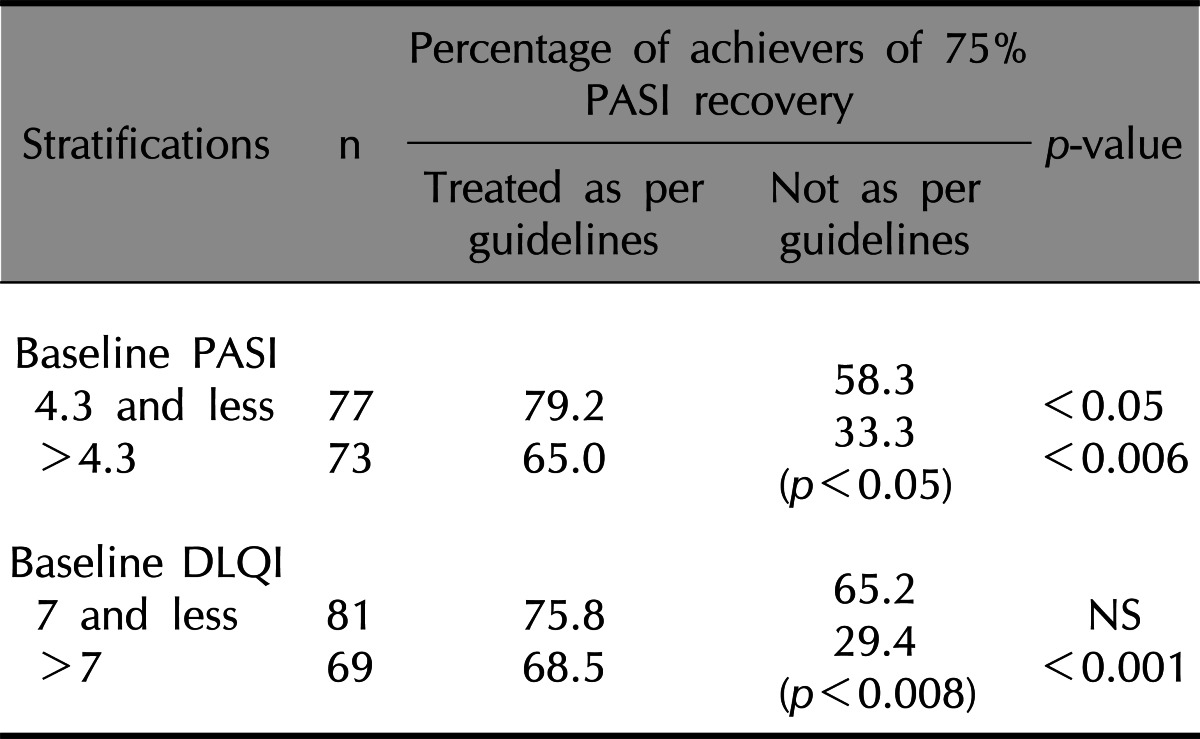

In patients with less deterioration in quality of life no significant differences occurred in outcome whether adhering to or digressing from treatment guidelines. Adherence to guidelines significantly improved treatment outcomes in patients bearing greater degradation in quality of life. Similarly, guideline adherence was also significantly more influential for high therapeutic outcome in more severe physical diseases (PASI) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Stratifications of Baseline Disease Severity as higher or lower than medians of PASI (4.3) and DLQI (7), and overall percentage of cases achieving 75% or more recovery in PASI when treated adhering or digressing guidelines

PASI: psoriasis area severity index, DLQI: dermatology life quality index, NS: non significant.

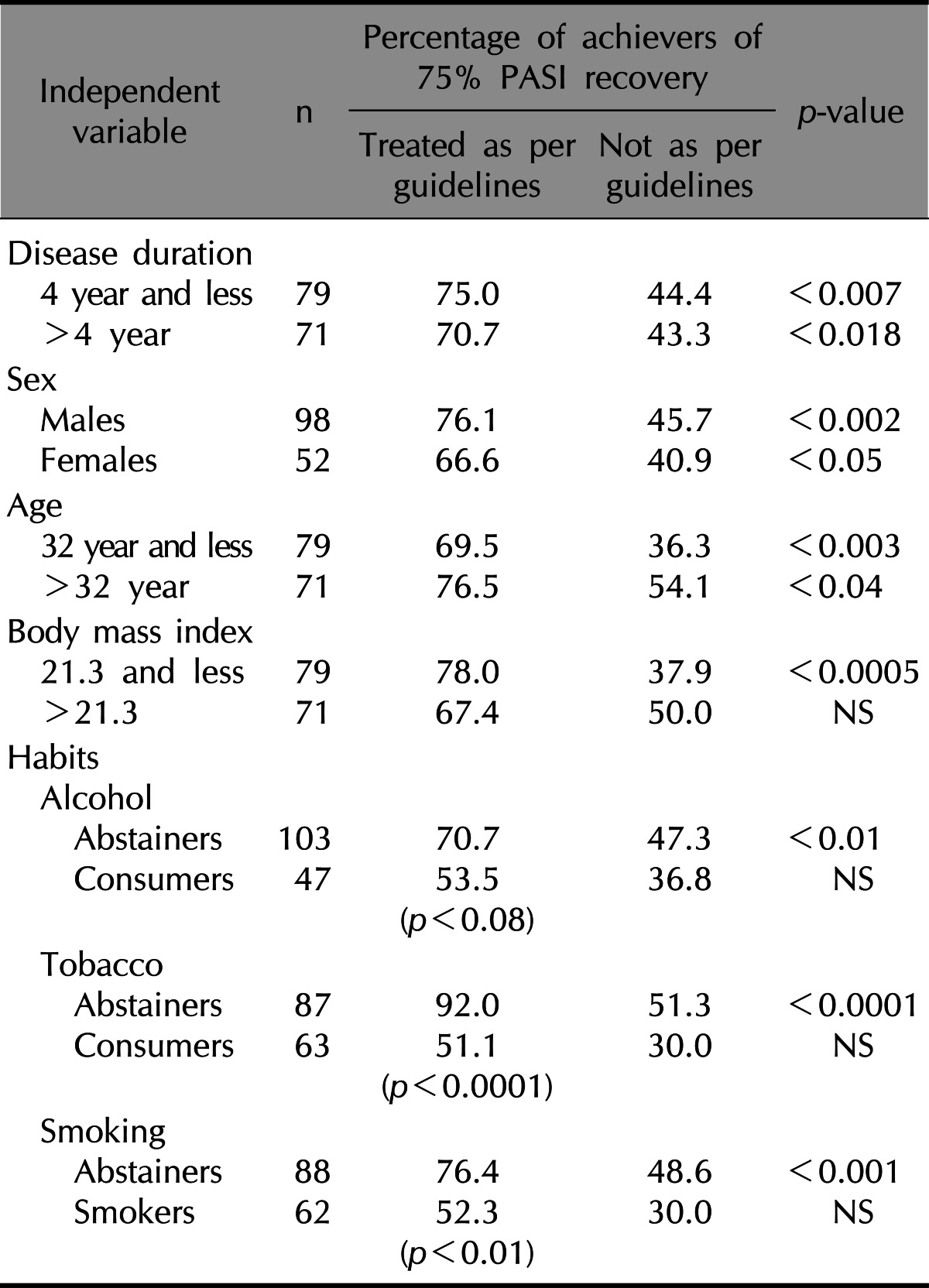

Therapy adhering to guidelines yielded significantly superior recovery irrespective of sex, age or disease duration. Patients with higher body mass indices did not respond differently to therapy adhering to or digressing from guidelines. Alcohol, tobacco or smoking habit very significantly compromised therapeutic responses and thus overtly eclipsed any manifestation of differential outcomes with therapy adhering to or digressing from guidelines (Table 5).

Table 5.

Percentage of cases attaining 75% or higher recovery in PASI in those treated adhering or digressing guidelines with regard to differences of independent variables

PASI: psoriasis area severity index, NS: non significant.

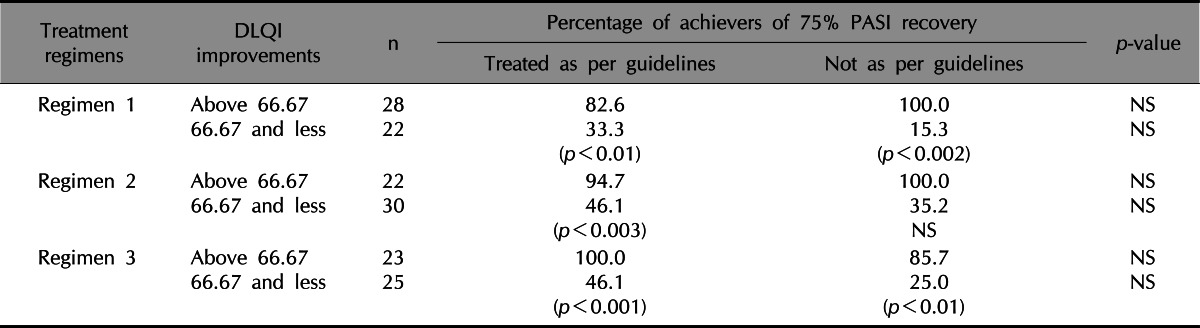

Higher improvement of DLQI was a strong predictor of high rates of PASI recovery disregarding adherence or digression of therapeutic guidelines in all treatment regimens (Table 6).

Table 6.

Percentage of cases attaining 75% or higher recovery in PASI concurrent to DLQI improvement above or below median 66.67 when treated by different regimens either adhering or digressing guidelines

PASI: psoriasis area severity index, DLQI: dermatology life quality index, NS: non significant.

DISCUSSION

Preponderance of males in plaque psoriasis seen in our study is in agreement to earlier reports14-16. The occurrence of peak prevalence in females earlier in age compared to males is also consistent with reports17. The highest prevalence inclusive of both sexes was under 40 years of age, which matches to the reported onset of psoriasis under 20 years of age in one third of all psoriasis cases in the region18. This is also close to that reported by Sharma and Sapaha (1984)19. A vast majority of cases in this study therefore constitute early onset, type-1 psoriasis that frequently associates with some human leucocyte antigen types and is destined to be more severe20. A European survey of 400 psoriasis patients in contrast, concluded an equal prevalence of early and late onset disease16. The pattern of the afflicted site is in agreement with a well-known preponderance of extremities, scalp and trunk.

The severity of disease in terms of PASI scores increased with disease duration indicating the progressive profile of disease which is known for the early onset disease phenotype as indicated in the majority of cases in the study. Degraded dermatologic quality of life exhibited a proportional association with physical severity of disease thus indicating an intimate mutual bearing which may be the cause or effect or both.

The outcomes were compromised with the treatment was either less or in excess of that recommended in therapeutic guidelines. This suggests the need for adequate treatment and the possibility of unresponsiveness to treatment respectively in the mild and severe disease spectra. Location considerations also guide treatment decision, and the results support the need for a more than ordinary address to disease on resistant sites and lesions on intertriginous sites.

Under treatment may fail to control inflammation while over treatment may adversely affect the physiological integrity of skin with the inability to control keratinocyte dysregulation, typical of the disease4. Conventional drugs employed in psoriasis therapy are reported to adversely influence dermal lipids, particularly ceramides21,22. Lipid disturbances are as such implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis23-25. A report of the elevated homocysteine profile in psoriasis26, characterizes a mode of aggravation of inflammation. Certain antipsoriatic medications may further endorse this27-29 which is potentially compromising for the therapeutic outcome.

It is noteworthy that cases wherein deterioration in quality of life is less, it was not necessary to adhere to therapeutic guidelines for a higher outcome. However, it was important in cases with greater deterioration in quality of life. It may be pertinent to understand whether an over treatment contributes to worsening quality of life and whether the same is subject to monitor. Further, good improvement of quality of life was associated also with good recovery in terms of PASI score, independently of the guidelines. It indicates the significance of stress determinants playing more of a causal role in physical disease. Stress, the singularly most important basis for degradation of quality of life is understood to aggravate immune dysfunction30 and worsen the inflammatory process31. There are reports that stress may be an important pathogenic element in the active form of psoriasis30. Therapeutic digression may be apt to worsen endogenous mechanisms that resist consequences of stress on the physical disease process.

Superior therapeutic outcomes by adherence to guidelines were consistent for different ages and disease duration. Thus benefits of adhering guidelines occur through mechanisms sustained in disease irrespective of age and duration. Less disturbance of skin physiology seems to match such possibility. Greater significance of adhering guidelines in more severe disease may indicate the need for an optimal therapeutic address to progressive pathogenic events. The latter include vascular abnormalities, activities of polymorphonuclear leucocytes and T cells, release of proinflammatory cytokines, keratinocyte hyperproliferation and altered epidermal differentiation resulting in scaling32. The approach of guidelines possibly makes a balanced address to interactive pathogenic mechanisms while digression results in some kind of disarray. Only marginally less responsiveness in females is in agreement to relatively heightened autoimmune phenomena in females33, relevant to the pathogenesis of psoriasis, of the early onset variety.

No significant differences in presenting severity of disease were seen in patients with relatively lower and higher body mass indices. However, adherence to therapeutic guidelines failed to provide a superior therapeutic outcome in patients with higher body mass indices. Obviously, there is need to understand the psoriasis phenotype in overweight patients. As such co-morbid association of psoriasis with overweight related diseases like diabetes and coronary disease has been recognized34,35. This may represent a syndromic variant, which is inadequately considered for address in current guidelines of psoriasis therapy.

Alcohol, tobacco and smoking habits markedly hamper response to conventional psoriasis therapy as per the study observation. These are known to worsen inflammation, cause lipid disturbances, and may be indicative of the heightened susceptibility to stress36-38. These may also indicate potential threats to therapeutic compliance. Emphasis on addressing such habits in patients is mandated in standard guidelines, particularly elaborating upon their prevalence in the psoriasis population at large.

Treatment of plaque psoriasis at our centre entirely relied on conventional older drug therapy. Resorting to alternatives like vitamin D3 analogues, newer retinoids or immunosuppressant cyclosporine was not made in any of the cases. Apparently, traditional conversance with such drugs while catering to patients largely from low and middle socioeconomic classes is the reason. Findings for some poor responding patient categories make a strong case for trying such alternatives instead of digressing guidelines resorting to over treatment or under treatment with traditional drugs. Vitamin D3 analogues are reported to be as effective as steroids and yield a synergistic benefit in psoriasis, reducing required mutual doses39. Tazarotene, the newer retinoid is especially inhibitory to the dermal infiltration of inflammatory cells40. Cyclosporine is a possible alternative to methotrexate without risk of inflicting hyperhomocysteinemia.

Obesity, female sex and other poorly responding cases of severe disease may well constitute indications for newer biological therapies. The promise of blocking tumor necrosis factor tumor necrosis factor α41, and monoclonal antibody against interleukin (IL) 12/IL 2342 deserve consideration for clinical use and better conversance. Most neglected is the therapeutic perspective of stress. The measure of deterioration for quality of life is emphasized as integral to patient assessment and a psychiatric reference in deserving cases would constitute an essential component of psoriasis therapy. Revised guidelines may effectively emphasize this aspect. Adverse habits like alcohol, smoking or tobacco use, known to contribute to proinflammatory and disturbed metabolic states may also indicate subclinical psychiatric morbidity. Weaning of the patients from such habits is a clear imperative for psoriasis management. In the long term, such habits may imply complications that merit consideration of biological therapies.

Consensus guidelines incorporate wide based wisdom and expertise. The empirical basis inherent in the guidelines is subject to scientific validation among varied phenotypes of psoriasis, an extremely immunogenetically heterogeneous disease43,44.

References

- 1.Woolf RT, Smith CH. How genetic variation affects patient response and outcome to therapy for psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:957–966. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan C, Menter A, Warren RB. The latest advances in pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics in the treatment of psoriasis. Mol Diagn Ther. 2010;14:81–93. doi: 10.1007/BF03256357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman P, Elder JT. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii37–ii39. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.030775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou X, Krueger JG, Kao MC, Lee E, Du F, Menter A, et al. Novel mechanisms of T-cell and dendritic cell activation revealed by profiling of psoriasis on the 63,100-element oligonucleotide array. Physiol Genomics. 2003;13:69–78. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00157.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubertret L. Recent progress in psoriasis treatment. Eur Dermatol Rev. 2006:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louden BA, Pearce DJ, Lang W, Feldman SR. A Simplified Psoriasis Area Severity Index (SPASI) for rating psoriasis severity in clinic patients. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callen JP, Krueger GG, Lebwohl M, McBurney EI, Mease P, Menter A, et al. AAD. AAD consensus statement on psoriasis therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:897–899. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)01870-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger GG, Feldman SR, Camisa C, Duvic M, Elder JT, Gottlieb AB, et al. Two considerations for patients with psoriasis and their clinicians: what defines mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis? What constitutes a clinically significant improvement when treating psoriasis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:281–285. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.106374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis--oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157:238–244. doi: 10.1159/000250839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jose RM, Roy DK, Vidyadharan R, Erdmann M. Burns area estimation-an error perpetuated. Burns. 2004;30:481–482. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay B, Lawrence CM. Measurement of involved surface area in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:565–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb04952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reich K, Mrowietz U. Treatment goals in psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:566–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta TK, Shah RN, Marquis L. A study of 300 cases of psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1978;44:242–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur I, Kumar B, Sharma KV, Kaur S. Epidemiology of psoriasis in a clinic from North India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1986;52:208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallbris L, Larsson P, Bergqvist S, Vingård E, Granath F, Ståhle M. Psoriasis phenotype at disease onset: clinical characterization of 400 adult cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:499–504. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:233–239. doi: 10.1002/art.24172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dogra S, Kaur I. Childhood psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:357–365. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.66580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma TP, Sapaha GC. Psoriasis a clinical study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1984;30:191–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henseler T, Christophers E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: characterization of two types of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:450–456. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao JS, Fluhr JW, Man MQ, Fowler AJ, Hachem JP, Crumrine D, et al. Short-term glucocorticoid treatment compromises both permeability barrier homeostasis and stratum corneum integrity: inhibition of epidermal lipid synthesis accounts for functional abnormalities. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coderch L, López O, de la Maza A, Parra JL. Ceramides and skin function. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:107–129. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horrobin DF. Essential fatty acids in clinical dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wertz PW, Swartzendruber DC, Abraham W, Madison KC, Downing DT. Essential fatty acids and epidermal integrity. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1381–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton JL. Dietary fatty acids and inflammatory skin disease. Lancet. 1989;1:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malerba M, Gisondi P, Radaeli A, Sala R, Calzavara Pinton PG, Girolomoni G. Plasma homocysteine and folate levels in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1165–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Libetta C, Sepe V, Zucchi M, Pisacco P, Portalupi V, Adamo G, et al. Influence of methylprednisolone on plasma homocysteine levels in cadaveric renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2893–2894. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd AS, Menter A. Erythrodermic psoriasis. Precipitating factors, course, and prognosis in 50 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:985–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baiqiu W, Songbin F, Guiyin Z, Pu L. Study of the relationship between psoriasis and the polymorphic site C677T of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Chin Med Sci J. 2000;15:119–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weigl BA. The significance of stress hormones (glucocorticoids, catecholamines) for eruptions and spontaneous remission phases in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:678–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid-Ott G, Jaeger B, Adamek C, Koch H, Lamprecht F, Kapp A, et al. Levels of circulating CD8(+) T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and eosinophils increase upon acute psychosocial stress in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:171–177. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stern RS. Psoriasis. Lancet. 1997;350:349–353. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ackerman LS. Sex hormones and the genesis of autoimmunity. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:371–376. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lander ES, Schork NJ. Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science. 1994;265:2037–2048. doi: 10.1126/science.8091226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risch N, Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science. 1996;273:1516–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins E. Alcohol, smoking and psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:107–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naldi L, Parazzini F, Brevi A, Peserico A, Veller Fornasa C, Grosso G, et al. Family history, smoking habits, alcohol consumption and risk of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:212–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Mediators of pruritus in psoriasis. Mediators Inflamm. 2007;2007:64727. doi: 10.1155/2007/64727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamba S, Lebwohl M. Combination therapy with vitamin D analogues. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(Suppl 58):27–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.144s58027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandraratna RA. Tazarotene--first of a new generation of receptor-selective retinoids. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(Suppl 49):18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb15662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gottlieb AB, Chamian F, Masud S, Cardinale I, Abello MV, Lowes MA, et al. TNF inhibition rapidly down-regulates multiple proinflammatory pathways in psoriasis plaques. J Immunol. 2005;175:2721–2729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, Yeilding N, Guzzo C, Wang Y, et al. PHOENIX 1 study investigators. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1) Lancet. 2008;371:1665–1674. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60725-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ståhle M, Sánchez F. The immunogenetics of psoriasis. ASHI Q. 2006;19:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhalerao J, Bowcock AM. The genetics of psoriasis: a complex disorder of the skin and immune system. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1537–1545. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]