Abstract

Purpose

As a follow-up for the validity study of Community Health Surveys (CHSs), the purpose of this study was to evaluate the factors affecting the accuracy of CHSs by investigating subjects' characteristics.

Materials and Methods

We used data from 11,217 participants (aged 19 years or older) who had participated in the CHS, conducted by a local government in 2008 and analyzed the variables affecting the sensitivity and specificity of hospitalization and outpatient visit.

Results

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that, factors related with the sensitivity of hospitalization and outpatient visit questions were gender, age, marital status, chronic diseases, medical checkup, the subjective health status and necessary medical services. Factors related with the specificity were gender, marital status, educational background, chronic diseases, medical checkup, alcohol consumption, necessary medical services and sadness.

Conclusion

This study revealed the subject-related factors associated with the validity of the CHS. Efforts to improve the sensitivity and the specificity from self-report questionnaires should consider how the characteristics of subjects may affect their responses.

Keywords: Validity, self-reported, healthcare utilization, community health survey

INTRODUCTION

Self-administered questionnaires are among the approaches used to examine the current status of public health, including health behaviors, healthcare utilization, disease prevalence, and so on. Despite the ease with which this method acquires data, especially in situations in which more objective records are inaccessible or unavailable,1 this approach is limited by its dependence on the subjectivity of responses, which may detract from the accuracy of information collected. Indeed, the accuracy of data obtained via self-report questionnaires is relatively low compared with that gathered from either medical records or insurance claims.2-4

Community health surveys (CHSs) have been conducted in Korea since 2008. They have illuminated the current status of public health in 253 local jurisdictions by querying 220,000 citizens and by consuming more than 12 billion won every year. Now, CHSs' scale such as subjects, and cost etc. is bigger than the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). In order that the results of CHSs are used as evidence for establishing and evaluating diverse local public health projects, it is necessary for CHSs to achieve a certain level of accuracy and to identify what factors affect the validity.

To-date, the only study of the validity of CHSs was performed by Rim, et al.5 Though this research revealed that CHSs have a certain level of sensitivity and specificity for healthcare utilization, such as rates of hospitalization and outpatient visits, it didn't show what factors are related with the sensitivity and the specificity. The sensitivity and specificity of questionnaires on healthcare utilization depend on subjects' knowledge and understanding of the relevant information, their ability to recall this information, and their willingness to report it.6 As a follow-up for the validity study of CHSs with the same data, we evaluated the factors affecting the accuracy of CHSs by investigating subjects' characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study data and subjects

This study included 11,217 Korean citizens. Of an initial sample consisting of the 12,449 respondents (aged 19 or older) who had participated in the CHS conducted by a local government in 2008, we excluded 1,206 individuals who refused to allow inclusion of their data in the relevant national statistics (e.g., health insurance, mortality data, etc.) maintained by other organizations and 26 individuals with problems with resident registration numbers who did allow their data to be used for these purposes. The 2008 CHS was conducted from August to October.

Methods

Reconfiguration of data for evaluation of accuracy

Responses to two questions on the CHS, regarding hospitalization and outpatient visits, were selected for analysis, because they were easy to compare with actual values. Respondents were asked to answer either "yes" or "no" to the following questions: "Have you been hospitalized during the past year?" and "Have you visited a hospital during the past 2 weeks?". The actual rates of the behaviors in question were based on whether the insurance benefits database of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) included the reported contacts. When citizens visit a healthcare institution in Korea, the healthcare institution sends claims for insurance benefits to HIRA, unless the patient is covered by workers' compensation or car insurance or is not insured. Next, using the patient's resident registration number, the CHS data are merged with those related to the insurance claim submitted to HIRA.

Establishment of variables

Definition of dependent variables

We defined the information contained in the claim for insurance benefits submitted to HIRA as the true rates of healthcare-services utilization. In terms of dependent variables, it was assumed that healthcare services were utilized when a respondent had been hospitalized within the last year or visited a healthcare institution as outpatient within 2 weeks of completing the questionnaire. We defined the sensitivity of each question as the rate at which individuals with insurance claims self-reported utilization of CHS services. The specificity of each question was defined as the rate at which those who claimed not to utilize healthcare services did not use such services according to the HIRA data.

Definition of independent variables

Validity-related variables included personal demographic characteristics, chronic diseases, health behaviors, and subjective health assessments. Personal characteristics included gender, age, educational background, marital status, and type of insurance. Educational background was divided into four categories according to duration of education. Marital status was categorized as "single", "living with spouse after marriage", and "living without spouse after marriage". Insurance was divided into "health insurance" and "public medical aid". Chronic disease, the actual presence of which was identified by a doctor's diagnosis, included hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke, and (osteo- or rhematoid) arthritis. Health behavior was categorized as getting a "medical checkup" within 2 years of the date of the survey, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Subjective health assessments were based on the following three questions: 1) "What do you think of your usual health? (Subjective health status)". Responses included (very) good, fair, and (very) poor. 2) "During the past year, have you ever been unable to obtain medical services when you needed them? (Necessary medical services)". Respondents provided yes/no answers to this question. 3) "Have you ever experienced a sad or depressed mood that was serious enough to cause problems in your daily routine that lasted more than 2 consecutive weeks during the past year? (Sadness)". This question was also answered "yes" or "no".

Data analysis

SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), was used to analyze the data, and significance was set at a value of p<0.05. We performed a frequency analysis to ascertain the relationship between dependent and independent variables. Next, the initial logistic regression model comprised all variables which showed a p value at least <0.20 in the chi-square test, so that all possibly significantly contributing variables will not be missed. The results yielded the odds ratios (ORs) of variables associated with sensitivity and specificity at the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Konkuk University Hospital (approval number: KUH1230005). We received informed consents from all the participants in the interview survey.

RESULTS

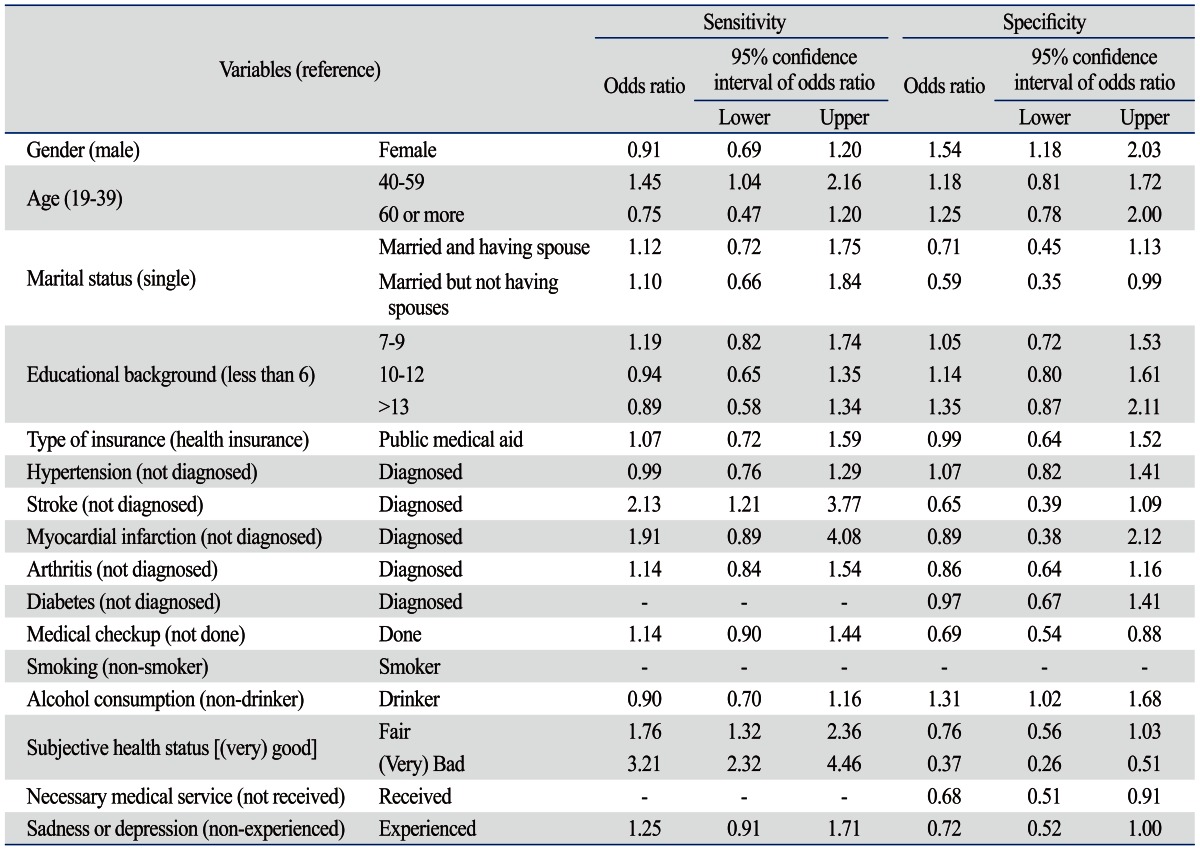

Factors related to the sensitivity and specificity of the hospitalization

The sensitivity and specificity of the hospitalization and the factors related to the sensitivity and the specificity of the hospitalization are shown in Table 1. The sensitivity and specificity were 54.8% and 96.4%, respectively. In the univariate analysis on the factors related to the sensitivity of the hospitalization, age group, marital status, educational background, type of insurance, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, arthritis, medical checkup, alcoholic consumption, subjective health status, and sadness had the statistical significance with p values <0.20. And in the univariate analysis on the factors related to the specificity of the hospitalization, age group, marital status, educational background, type of insurance, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, arthritis, diabetes, medical checkup, alcoholic consumption, subjective health status, necessary medical service and sadness had the statistical significance with p values <0.20.

Table 1.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Hospitalization by Variables

According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the OR for the sensitivity of the hospitalization in 40-59 years of age, compared to 19-39 years of age, was 1.45 (95% CI, 1.04-2.16). The OR for respondents who had suffered a stroke, compared to those who had not, was 2.13 (95% CI, 1.21-3.77). Compared to those who rated their health as (very) good, respondents who rated their health as fair or (very) bad showed an OR for the sensitivity of the hospitalization of 1.76 (95% CI, 1.32-2.36) or 3.21 (95% CI, 2.32-4.46) (Table 2). The OR for the specificity of the hospitalization in females compared to males was 1.54 (95% CI, 1.18-2.03), and the OR of those living without their spouse to single respondents was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-0.99). Additionally, the OR of those who had received a medical checkup to those who had not was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.54-0.88) and the OR for the specificity of the hospitalization in those who consumed alcohol compared to those who did not was 1.31 (95% CI, 1.02-1.68). Furthermore, the OR of those who had received necessary medical services to those who had not was 0.68 (95% CI, 0.51-0.91).

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis on Sensitivity and Specificity for Hospitalization

Factors related to the sensitivity and specificity of the outpatient visit

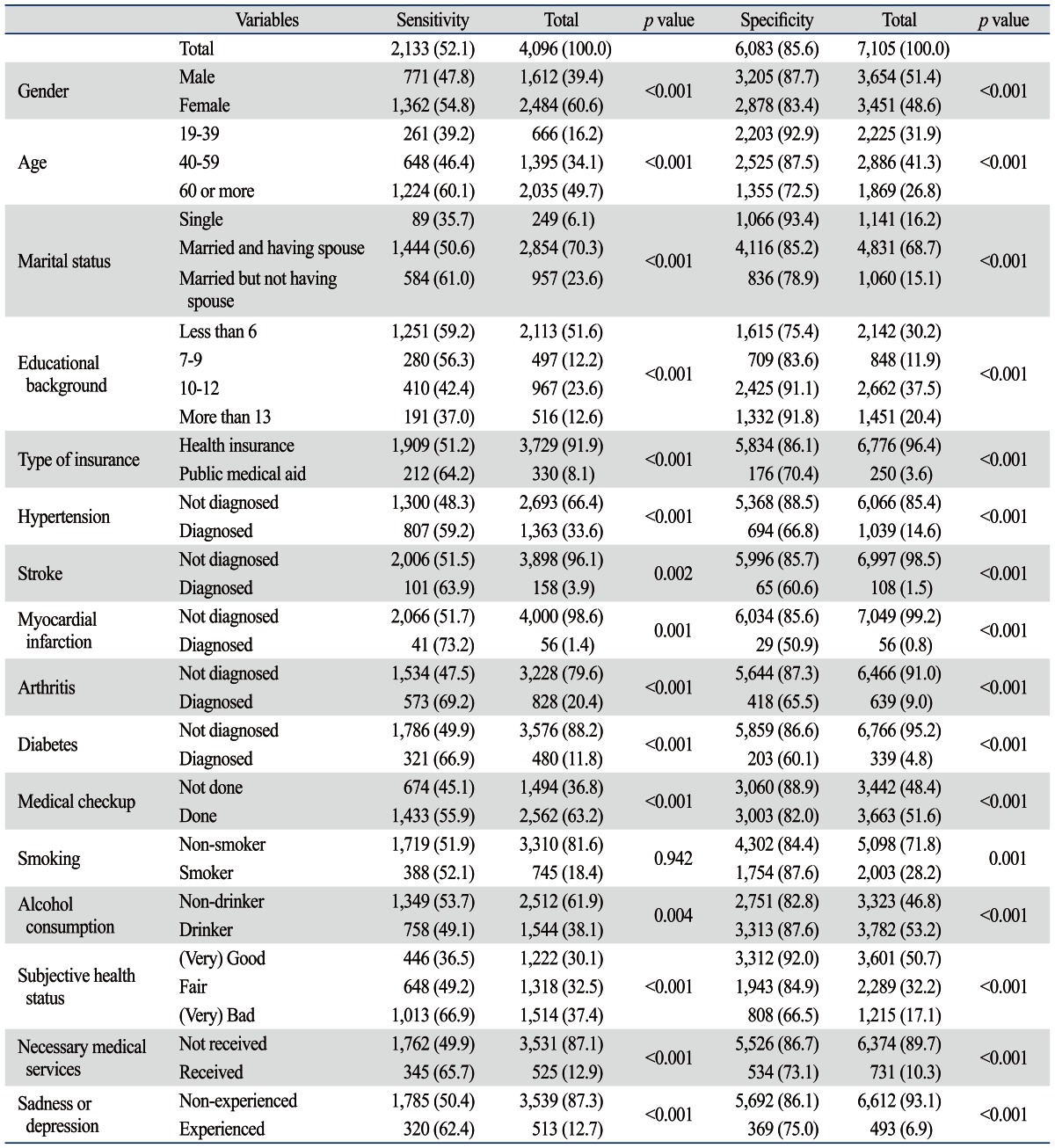

The sensitivity and specificity of the outpatient visit and the factors related to the sensitivity and the specificity of the outpatient visit are shown in Table 3. The sensitivity and specificity were 52.1% and 85.6%, respectively. In the univariate analysis on the factors related to the sensitivity of the outpatient visit, gender, age group, marital status, educational background, type of insurance, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, arthritis, diabetes, medical checkup, alcoholic consumption, subjective health status, necessary medical service and sadness had the statistical significance with p values <0.20. And in the univariate analysis on the factors related to the specificity of the outpatient visit, gender, age group, marital status, educational background, type of insurance, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, arthritis, diabetes, medical checkup, smoking, alcoholic consumption, subjective health status, necessary medical service and sadness had the statistical significance with p values <0.20.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Outpatient Visit by Variables

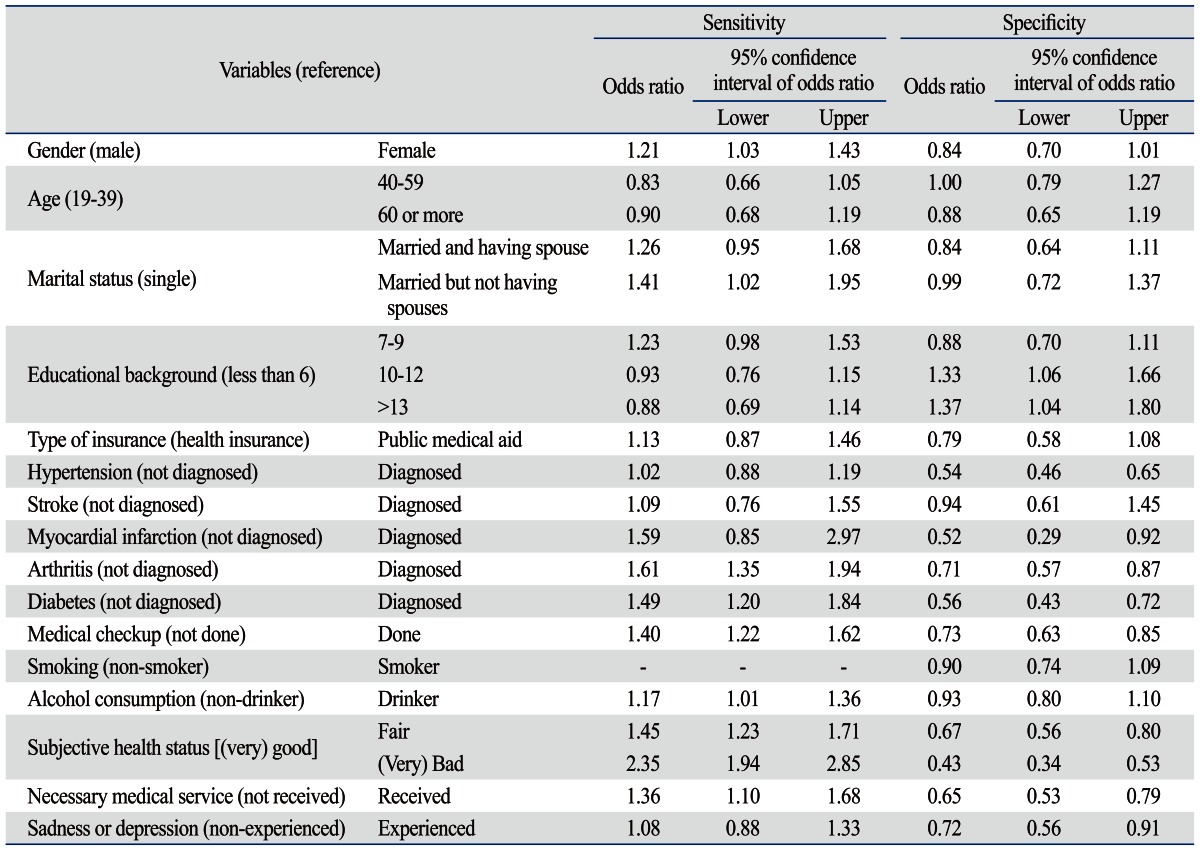

According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the OR for the sensitivity of outpatient visits in females compared to males was 1.21 (95% CI, 1.03-1.43) and the OR of those living without their spouse to single respondents was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.02-1.95). The OR for respondents who had suffered arthritis or diabetes compared to those who had not was 1.61 (95% CI, 1.35-1.94) or 1.49 (95% CI, 1.20-1.84). The OR of those who had received a medical checkup to those who had not was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.22-1.62) and the OR for the specificity of the outpatient visits in those who consumed alcohol compared to those who did not was 1.17 (95% CI, 1.01-1.36). Compared to those who rated their health as (very) good, respondents who rated their health as fair or (very) bad showed an OR for the sensitivity of the outpatient visit of 1.45 (95% CI, 1.23-1.71) or 2.35 (95% CI, 1.94-2.85). The OR of those who did not obtain necessary medical services compared to those who did was 1.36 (95% CI, 1.10-1.68) (Table 4). The OR for the specificity of outpatient visits for education with 10-12 years or more than 13 ones compared to that with less than 6 years was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.06-1.66). The OR for respondents who had suffered hypertension, myocardial infarction, arthritis, or diabetes compared to those who had not was 0.54 (95% CI, 0.46-0.65), 0.52 (95% CI, 0.29-0.92), 0.71 (95% CI: 0.57-0.87), or 0.56 (95% CI: 0.43-0.72), respectively. The OR of those who had received a medical checkup to those who had not was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.63-0.85). Compared to those who rated their health as (very) good, respondents who rated their health as fair and (very) bad showed an OR for the specificity of the outpatient visit of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.56-0.80) or 0.43 (95% CI, 0.34-0.53). The OR of those who did not obtain necessary medical services compared to those who did was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.53-0.79) and the OR of those who did not experience sadness compared to those who did was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.91).

Table 4.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis on Sensitivity and Specificity for Outpatient Visit

DISCUSSION

The CHS that addresses demographic characteristics, rates of disease and healthcare utilization, vaccination and health behavior, quality of life, and socio-physical environment is now becoming the main data source on the health of 253 jurisdictions of public health center. This point is the distinctive advantage of CHSs compared with KNHANES which has only national health indices. As a result, information obtained by the CHS from respondents and data on time-series changes can be used to establish agendas for public health programs or to evaluate the results of such programs. However, none of the questions, with the exception of those about rates of diseases and healthcare utilization, produces information that can be compared with objective data. Although rates of disease and healthcare utilization can be examined by reference to data (e.g., insurance claims, medical records, etc.) that are relatively more objective than those obtained via self-report surveys, these issues have been investigated via questionnaires due to the easier access to data, efficiency, and lower cost associated with this method. Thus, research on the degree to which data obtained via self-report surveys are accurate and on the factors associated with accuracy will enhance the usefulness of information regarding rates of diseases and healthcare utilization gathered by such methods.

This study that is the follow-up study for the validity of CHS was to identify subject characteristics related to sensitivity and specificity for purposes of evaluating the validity of the CHS. In this study, the sensitivity of hospitalization and outpatient visit questions was highest among married individuals living without their spouse, those with chronic diseases, those with poor health behavior, those who recently received medical checkups, and those with less favorable assessments of their health status. In contrast, specificity was highest in single individuals, those with more education, those without chronic diseases, those who had not received a medical checkup recently, and those with a more favorable assessment of their health status. In other words, those with poor health, whether judged objectively or subjectively, have higher sensitivity and lower specificity. Conversely, those with good health, judged either objectively or subjectively, have lower sensitivity and higher specificity.

This study tried to identify factors related to validity of some variables, but existing relevant literature suggests that kappa values represent the extent of the fit between obtained and true values and have presented findings concerning reliability in terms of comparisons with objective data. That is, kappa is an index of reproducibility or reliability, and can exclude the degree of agreement of two data by chance. If kappa is more than 0.75, then reliability between two data is interpreted as excellent; if kappa is more than 0.40 and under 0.75, it is fair or good; and if kappa is under 0.40, then it is poor.7 One of them showed the concordance between subjective and objective reports on healthcare utilization (hospitalization, outpatient visits), and was higher among those with frequent healthcare utilization than among those with infrequent utilization.8 Some studies suggest that age, gender, educational background, and ethnicity are associated with the accuracy of self-reports.9,10 In this study, specificity was higher in single individuals and in those with more education, whereas sensitivity was higher among married individuals living without their spouse. Additionally, some studies have reported that older age is the only demographic factor significantly associated with inaccurate and under-reported healthcare utilization.11,12 Indeed, other studies have reported that the accuracy of self-reports was not related to demographic factors such as education, gender, health status, socioeconomic status, and so on.3,13

Moreover, we found that sensitivity and specificity differed as a function of whether subjects had been diagnosed with chronic diseases. Sensitivity for both hospitalization and outpatient visits was higher in those with chronic diseases, whereas specificity was higher in those without chronic diseases. According to a comparative study reviewing self-reports and doctors' claim records for hypertension, the kappa value reflecting the concordance rate in those with diabetes was 0.42, which was significantly lower than that (0.56) among those without diabetes.14 In this study, however, the kappa value reflecting agreement between self-report and insurance claims data was higher in those with hypertension (0.58) than in those without this condition (0.55) with respect to hospitalization, and higher in those without hypertension (0.50) than in those with hypertension (0.25) in terms of outpatient visits. This difference between the concordance rates for hospitalization and outpatient visits can be explained as follows. Because hospitalization does not occur often, those with hypertension who were highly interested in health would be expected to remember with greater accuracy whether they had been hospitalized. On the other hand, because outpatient visits are common among those who suffer from hypertension, it is possible that patients with this condition would provide inaccurate information about their visits to healthcare institutions during the past 2 weeks, due to failure to remember if their last visit occurred within that time frame. In fact, specificity for outpatient visits was high among those without hypertension (88.5%), whereas it was low among those with high blood pressure (66.8%).

Studies comparing medical records and self-reports with respect to eye examinations and diabetes found the following kappa values for different levels of subjective assessments of health status: 0.15 among those rating their health as very good, 0.23 among those rating it as good, 0.25 among those rating it as fair, 0.25 among those rating it as bad, and 0.24 as those rating it as very bad, confirming that self-rated assessments were not related to objective evaluations of health status.15 This study found that sensitivity for hospitalization and outpatient visits was higher among those who assessed their health to be poor than among those who assessed it to be good. On the other hand, specificity was higher among those who evaluated their health to be good than among those who assessed their health to be poor. The kappa values for the concordance rates for hospitalization by subjective ratings of health were 0.46 for those rating their health as very good or good, 0.55 for those rating their health as fair, and 0.60 for those rating their health as very bad or bad, whereas those for outpatient visits were 0.33, 0.36, and 0.33, respectively. Among those who did not receive necessary medical services and those experiencing depression or sadness, sensitivity was high, whereas the specificity was low with respect to outpatient visits.

However, this study has the following limitations: first, we did not examine factors other than demographic characteristics of respondents that may influence validity. In particular, because more than 70 interviewers in 13 areas participated in this survey, it is possible that some of the results were due to differences in interviewing dynamics. In addition, we didn't fully consider respondents' medical condition. We only used major chronic diseases, not severe disease such as severe cardiac insufficiency, severe chronic kidney disease (mainly end stage renal disease), peripheral artery disease, cancer and so on. It was because this study used the secondary data. So, these issues should be evaluated in future research. Second, because the criteria for validity were limited to comparisons with health insurance data, it could be classified into 'those without healthcare utilization' in this study, which may in turn decrease specificity even though other types of insurance such as workers' compensation and car insurance are available. This kind of problem can be overcome by using other comparison data as the true values. Third, because data from only rural areas (13 public health centers) were used, the results of this study may not be generalized to large cities such as Seoul. Moreover, because the questions used for the validity assessment were limited to those on hospitalization and outpatient visits, the results are not applicable to the utilization patterns of other healthcare services, such as visits to emergency medical centers or dentists. This problem could be overcome by examining factors associated with the sensitivity and specificity of the entire CHS or by increasing the number of comparison variables.

In summary, this study revealed the subject-related factors associated with the validity of the CHS. Efforts to improve the sensitivity and the specificity from self-reported questionnaires should consider how the characteristics of subjects may affect their responses. One of them is to educate interviewers about how to elicit more accurate answers to questions about healthcare utilization before they begin to conduct CHSs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Konkuk University in 2012.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lerner DJ, Lee J. Measuring Health-Related Work Productivity with Self-Reports. In: Kessler RC, Stang PE, editors. Health and Work Productivity: Making the Business Case for Quality Health Care. Chicaco, IL: University of Chicaco Press; 2006. pp. 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans C, Crawford B. Patient self-reports in pharmacoeconomic studies. Their use and impact on study validity. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:241–256. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199915030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, Lorig KR. Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrou S, Murray L, Cooper P, Davidson LL. The accuracy of self-reported healthcare resource utilization in health economic studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;18:705–710. doi: 10.1017/s026646230200051x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rim H, Kim H, Lee K, Chang S, Hovell MF, Kim YT, et al. Validity of self-reported healthcare utilization data in the Community Health Survey in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1409–1414. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.11.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman N, Lin IF, Weinstein M, Lin YH. Evaluating the quality of self-reports of hypertension and diabetes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn Y, Yoo K, Park B. Manual for medical statistics. Seoul, Korea: Press of Seoul National University; 2005. pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raebel MA, Malone DC, Conner DA, Xu S, Porter JA, Lanty FA. Health services use and health care costs of obese and nonobese individuals. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2135–2140. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:217–235. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Short ME, Goetzel RZ, Pei X, Tabrizi MJ, Ozminkowski RJ, Gibson TB, et al. How accurate are self-reports? Analysis of self-reported health care utilization and absence when compared with administrative data. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:786–796. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a86671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallihan DB, Stump TE, Callahan CM. Accuracy of self-reported health services use and patterns of care among urban older adults. Med Care. 1999;37:662–670. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raina P, Torrance-Rynard V, Wong M, Woodward C. Agreement between self-reported and routinely collected health-care utilization data among seniors. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:751–774. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall SF, Deapen D, Allen M, Anton-Culver H, Bernstein L, Horn-Ross PL, et al. Validating California teachers study self-reports of recent hospitalization: comparison with California hospital discharge data. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1012–1020. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muhajarine N, Mustard C, Roos LL, Young TK, Gelskey DE. Comparison of survey and physician claims data for detecting hypertension. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:711–718. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckles GL, Williamson DF, Brown AF, Gregg EW, Karter AJ, Kim C, et al. Agreement between self-reports and medical records was only fair in a cross-sectional study of performance of annual eye examinations among adults with diabetes in managed care. Med Care. 2007;45:876–883. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca95fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]