Abstract

Background

Particulate air pollution, including from motor vehicles, is associated with cardiovascular disease.

Objectives

To describe lessons learned from installing air filtration units in public housing apartments next to a major highway.

Methods

We reviewed experience with recruitment, retention and acceptance of the air filtration units.

Results

Recruitment and retention have been challenging, but similar to other studies in public housing. Equipment noise and overheated apartments during hot weather have been notable complaints from participants. In addition, we found that families with members with Alzheimer’s or mental disability were less able to tolerate the equipment.

Conclusions

For this research the primary lesson is that working closely with each participant is important. A future public health program would need to address issues of noise and heat to make the intervention more acceptable to residents.

Keywords: Particulate matter, CBPR, community-based participatory research, public housing, air filtration, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Airborne particulate matter (PM) is extremely toxic and has been estimated to cause more health and economic harm than all other environmental pollutants regulated by the US EPA combined.1–3 Combustion sources, including motor vehicles, produce PM. Studies have shown that the tiniest particles, called ultrafine particles (UFP; <0.1 µm), are elevated next to highways and heavily traveled roads.4 Further, studies have also found associations between living near heavily-trafficked roadways and cardiovascular disease5, including blood markers of inflammation6–8, coronary atherosclerosis9 and mortality from coronary heart disease.10

Installation of High Efficiency Particulate Arrestance (HEPA) filters can reduce PM levels in buildings.11–13 It appears that in-home HEPA filtration can be used to improve asthma in children.14–15 Studies have begun to test whether reducing PM affects biomarkers of cardiovascular disease.16–18 Two studies found improvements, one in microvascular function and the other in endothelial function and inflammation.17–18

Our objective was to describe lessons learned from installing air filtration units in public housing apartments next to a major highway. Social acceptability can undermine application of a theoretically viable intervention. Studies of in-home environmental interventions in low-income populations have often struggled with recruitment and retention, a possible sign that real-world application could be challenging.19–22

Ours is a 3-year community-based participatory research (CBPR) project with participation of the community partners in all aspects of the science, including developing the proposal, leading the study, collecting, analyzing, interpreting the data and publishing results. The partners are the City of Somerville Housing Division, Somerville Housing Authority; the Somerville Transportation Equity Partnership (STEP); and Tufts University Schools of Engineering and Medicine.

The project Steering Committee, which consists of all partners, meets bi-weekly to discuss all aspects of the study, with contributions from everyone present. Particular partners tend to focus on specific areas of the work. The grant is to the city and a representative of the Housing Division manages it and oversees the steering committee agenda. The university plays a leading role with the HEPA and monitoring and with analysis of the health data. STEP has helped to lead the field work and regularly contributes updates from the scientific literature.

This study grew out of a larger observational CBPR study, the Community Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health (CAFEH) study.23 The in-home filtration intervention was a direct response to community interest in reducing exposure to highway pollution. Earlier recruitment efforts by the CAFEH study probably deepened awareness of traffic pollution in the target community.

Recruitment was conducted at the Mystic Housing Development in Somerville, a public housing development located immediately adjacent to Interstate-93 (I-93) and state Route 38. This is an area where we have previously reported elevated levels of UFP.24 Participants had to be at least 40 years old, non-smoking and not allow smoking in their homes. Study materials were available in English, Haitian Creole, Portuguese and Spanish.

Methods

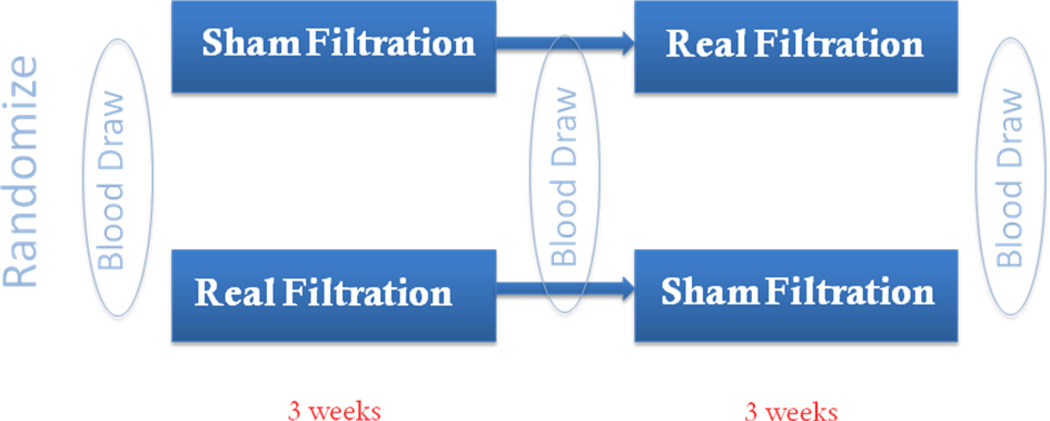

The design was a crossover study of the health benefits of in-home HEPA filtration in 20 homes. Two homes were enrolled at a time and each home received either real or sham filters for a three-week period and then each was switched and followed for a second three-week period (Figure 1). We chose 3-weeks because biomarkers of inflammation appear to change in response to UFP in that time.25–26 Participants were blinded as to the filtration type. The main pollutant monitored was particle number concentration (PNC) which is a reasonable surrogate for UFP since ultrafine particles typically comprise >80% of the PNC. In our study particles were measured continuously, in contrast to other in-home HEPA interventions that have only measured PM for limited periods.11–13

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the randomized cross-over study design.

The apartments were 2–4 bedrooms with a ceiling height of 2.4 m. Dimensions ranged from 3.1 m – 3.8 m × 4.1 m – 5.1 m. The size of the apartment may have affected the efficiency of filtration. The HEPA unit was designed for a room of about 1000 ft3 or 3.4 m × 3.4 m with a 2.4 meter ceiling. The number of occupants in the apartments ranged from 2–5. It is worth noting that distinguishing between people who live in these apartments and those who spend considerable time there was difficult.

We obtained names and contact information for apartments from the Somerville Housing Authority. We were interested in apartments within 200 meters of the highway that had a bedroom window facing the highway. We created a ranking system based on proximity to the highway, availability of a bedroom window facing the highway and whether there was another building obstructing the highway. Priority was given to apartments within 100 meters where PNC is highest. We identified 203 units, 106 of which were within 100 meters.

HEPA air filtration units (HEPAiRx) were loaned by Air Innovations, Inc. (www.airinnovations.com; Syracuse, NY). These units have been shown to reduce PM levels in indoor air and evidence suggests benefits for asthmatic children.14 The units were installed in a living room window because bedrooms proved too small for all the equipment (Figure 2). The HEPA filters were maintained by the project team as trained by Air Innovations staff. We provided one new filter per home and compensated participants $100 for the estimated cost of electricity use.

Figure 2.

Typical arrangement of the HEPA filter (top right) and condensation particle counter (bottom right) shown on an apartment floor plan.

To maximize particle removal, HEPA filters were set to recirculate indoor air and we asked that windows be kept shut as much as possible. The HEPA filters operated at 49 decibels, about the same noise level as window-mounted air conditioners. Water-based condensation particle counters (CPC; Model 3783, TSI, Minneapolis, MN) were installed in the living room (Figure 2) to enumerate PNC in the 7–3000 nm size range.

Portuguese and Spanish surveyors were recruited from the housing development and we also employed two surveyors from the larger CAFEH study. A veteran surveyor and the field manager from STEP conducted training for the new surveyors. We had difficulty recruiting Haitian Creole speaking surveyors initially, but eventually found a Somerville resident, a college student, who was bilingual.

Recruitment efforts included two community meetings. Flyers were dropped at all eligible apartments for the first meeting and all eligible Haitian Creole speakers for the 2nd meeting. The first meeting was attended by about 12 residents and several agreed to participate in the study. No residents attended the second meeting. We also participated in an annual summer picnic at the housing development and attended two resident association meetings to promote interest in the study.

Trained recruiters went door-to-door to engage participants. For interested residents, an appointment was arranged to explain the study in detail. If the resident agreed to participate they signed a consent form and completed a questionnaire about demographics, residential history, time activity, window opening, air conditioner use, exposure to combustion sources, diet, physical activity, stress, health conditions, medications and perception of risk.

Each participant’s height, weight and blood lipids were measured at the beginning of the intervention. Blood samples were collected and blood pressure measured three times each: immediately prior to turning on the HEPA filters, just prior to the switch over from sham to real filtration (or vice versa) and just prior to turning off the filters at the end of the intervention period (Figure 1). Blood from a finger stick was analyzed for lipid profile at the first appointment using a portable device. Nurses from the Visiting Nurses Association of Eastern MA, who spoke Haitian Creole and Spanish and were familiar with the housing development, performed the blood draws. Stored samples will be assayed for inflammatory markers at the end of the study.23 We provided $25 gift cards at the first interview and at each blood draw, the same amount we used in prior studies in the same population. Availability and expense of equipment plus the intensive effort required to manage each participant limited us to a pilot study of limited size. The study was approved by the Tufts IRB.

From the first visit to each home we tried to build an effective working relationship with each participant. We tried to learn a little about each participant while allowing them to know us. We also tried to build a relationship with family members. Every time we went to their homes we asked how everything was during the last week and if they had any questions/concerns regarding the study. At the end of each visit, we explained to them what to expect during the next visit. We were careful to position the equipment in homes and to schedule appointment to minimize inconvenience for the participants.

Results

Recruitment

Our goal is for residents from 20 apartments to complete the study. Recruitment has been slow and challenging. We report here on the first 10 homes completed (Table 1). Many people were not at home or did not answer the door. We had hoped to recruit some of the numerous white English speaking residents; however, most of them smoked or allowed smoking in the home, which disqualified them. Also, we encountered people who did not speak the languages for which we were prepared, including Chinese and Vietnamese. In addition, although we had documents in Haitian Creole and there were many Haitians in the development who appeared to be eligible, we initially had difficulty hiring culturally and linguistically matched field staff.

Table 1.

Numbers of study recruits and completions.

| Number | Percent recruited/retained |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total number of apartments we identified with at least one family member 40 years or older based on records kept by the city. | 203 | -- |

| Apartments approached by end of 2011 that had residents eligible for the study | 27 | -- |

| Apartments in which one or more participants signed consent forms by end of 2011 | 16 | 59%* |

| Apartments that completed the 6-week intervention by end of 2011 | 10 | 63%** |

Relative to apartments approached that had eligible residents.

Relative to those who started the intervention study.

Preliminary advice to us from a resident was to avoid first-floor apartments because of risk of vandalism to the HEPA units sticking out of windows. With limited options we expanded to first floors and with no vandalism. On three occasions we spoke to residents who appeared to agree to participate, only to return and have them tell us that they were no longer interested. This experience led us to avoid encouraging potential participants who seemed hesitant.

Retention

Retention was important as we were installing equipment and following people for 6 weeks. To date, six participants have dropped out while 10 completed the study (Table 2). Each drop out was a loss of invested time and effort and affected the overall scheduling of the interventions. Despite our efforts to insure that people we approached would be in their home for the 6-week period, we had two instances in which participants surprised us by announcing changed plans. One left the country after the fourth week; the other relocated to another state. We were unable to determine whether we had communicated poorly or their plans had simply changed.

Table 2.

Participants who left the study and their reasons for leaving.

| Home 1 | We removed the participant from the study since they were not going to be at home for the 6 weeks. The person was moving out of state. |

| Home 2 | Participant removed himself from the study due to trust issues. He felt we were taking advantage of him. He thought we would not pay him what we owned him for his involvement in the study. He wanted cash instead of gift cards. |

| Home 3 | Participants (2) left the study because the apartment was too hot. One of the participants complaint about the noise although they stated that this was not the issue that made them quit the study. |

| Home 4 | Participant left the study because the HEPA unit and CPC pump were too loud. She could not tolerate the noise. |

| Home 5 | Participant left the study because his wife could not tolerate the noise of the equipment. |

| Home 6 | Participant left the study because her son (mental disability) could not tolerate the noise of the equipment. |

In two instances participants removed themselves from the study because a family member was unhappy with the equipment noise. In one case the participant had an adult child with emotional disabilities who became agitated. In general, family members with Alzheimer’s or mental disability and households that were chaotic were challenging to recruit and retain. We subsequently modified our approach to include consultation with or about family members who might be adversely impacted by the study.

During the summer we had one participant drop out because their apartment was too hot. The HEPA unit cools, but in this case, because of extremely hot weather; the cooling capacity of the unit was insufficient. Providing a fan did not resolve the issue. Another participant complained about heat, but completed the intervention while using a fan for additional cooling.

One resident’s complaints were about stipends and electricity remuneration. They told us that he received food stamps so a gift card for groceries was not helpful and he preferred cash. We considered providing cash, however, the university would not issue cash without obtaining a social security number and the participant did not want his personal information recorded. The participant left the study in the 5th week.

Equipment

We put the CPC pump in an insulated box to reduce noise, but there was nothing we could do to reduce noise from the HEPA units (which were louder). Some participants suggested that the noise from our equipment was more bothersome than air conditioners or highway traffic because it interfered with watching television and making telephone calls. Thus, placing the HEPA units in the living room where these activities take place may have contributed to the problem. Placing the equipment in the living room was sometimes challenging since the CPC pump was in a large box (80×60×45 cm). Due to furniture we could not always position the CPC in our preferred location, across the room, facing the HEPA unit.

Early in the study, we had technical issues with the CPCs requiring us to visit homes more than once each week. Participants did not seem troubled by our presence in their homes, but some expressed frustration with scheduling appointments. The logistics of scheduling appointments was also challenging for the team, which consisted of the nurse, the field manager, the person performing consents and surveys, and the person responsible for the HEPA and CPCs. Because of the precise timing necessary for taking blood samples relative to installing, switching or removing HEPA units, a missed appointment adversely affected the whole team.

We can compare our experience with the HEPA intervention to the CAFEH study.23 CAFEH involved door-to-door recruiting for a survey and attending up to 2 clinic visits. In CAFEH, participants spent ~3 hours over 1–3 days. The response rate for CAFEH in Somerville was about 58%. The recruitment rate for the HEPA intervention is 59% (Table 1). The main difference in eligibility compared to CAFEH is that we excluded smokers for the HEPA study. In addition, recruitment was restricted to a smaller set of homes, those Mystic Housing Development residents who lived within 200 meters of the highway. Still, recruitment was comparable between the two studies. The success rates of both were also similar to other recruitment in public housing in nearby Boston.27–28

If we define retention in CAFEH as completing a subsequent visit, in the Somerville study area we had success about 69% of the time. A sub-study of CAFEH installed CPC monitors without filtration units in 18 homes. There were no dropouts among these homes, but the time was only 1–2 weeks. There were also complaints about CPC noise in these CAFEH homes. Completion of the in-home air filtration intervention was 63% of those who started. Thus, retention was similar between the larger, less intensive, involvement in CAFEH and the more intensive engagement with the filtration intervention. But in the filtration study each lost participant had a larger impact on the project because far more resources went into installing the equipment and collecting environmental and human data.

Discussion

There were numerous strengths to our approach including 1) having community/city partners that helped us recruit residents, 2) providing an intervention that residents saw as potentially helping them if it could be proven to be effective, 3) being open to learning from experience and adjusting as we went along, and 4) having team members who could interact well with the residents and establish mutual trust. These conclusions are broadly consistent with classic CBPR theory and practice29–30 as well as with reports of CBPR conducted specifically with public housing residents,31 particularly as they relate to building trust, a core principle of such partnerships. These sources also all point to the value of sustainability, something we are beginning to address across our research areas.

We feel that our partnership between community-based organizations (CBO), the city and the university was important to our efforts to recruit, retain and complete interventions in homes. Our city partner was in the Housing Department and well positioned to help the study obtain needed information. Our primary CBO (STEP) led the field operation and proved adept at facilitating recruitment and coordinating complex logistics.

During the planning stage of the study, the Mystic Housing Tenants Association participated in the study. However, the association had difficulties maintaining its own leadership and activities organizing the residents so their participation in the study became infrequent. Close to the end of the implementation phase of our project, when there was no longer any association participation, voluntary participation of individual residents partially compensated for the absence of the association. The Mystic Housing residents that we hired onto the field team and our bilingual/bicultural post doc and nurse contributed substantially to recruitment, retention and data collection.

It is important to consider how these lessons inform sustainability of in-home HEPA interventions. As noted earlier, other studies have found similar interventions challenging.19–22 One could imagine public housing authorities installing HEPA units in apartments near heavy traffic as a public health measure. From our experience if such a program were to be successful it would need to address the technical and social factors that we have encountered. These included noise from HEPA units, inability of the units to handle the hottest temperatures, smoking households and adverse responses by residents with mental or behavioral health problems. Other factors that we faced around recruitment and retention would appear to be limited to the research phase.

One option we intend to consider that might address some of these problems is to explore different HEPA units, possibly one that could be used in the bedroom, and that would function within existing heating and cooling systems, or ones that do not provide heating and cooling and are therefore quieter to operate.

In conclusion, this intervention study, was challenging because we were working in homes of low-income people many of whom were dealing with issues related to family dynamics, adjusting to a new culture and finances. It was important to have partners with credibility and trust, to have an intervention that addressed a community concern, and to have a responsive team that was able to quickly address problems. Ultimately, being responsive to the needs and concerns of participants, and being able to adapt to unanticipated problems that arose were critical. The level of resources and time needed to recruit and retain participants should not be underestimated.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank our field team members Doreen Jenkins, Maria Pontes, Migdalia Tracy, Tali Ruskin, Jozy Cantave, Yolande Louis and Kevin Stone. We are grateful to the Visiting Nurses Association of Eastern MA,, Patricia Calioro, for scheduling the clinical appointments, the nurses, Yslande Claude and Betsy Rodman, for the clinical visits and Jose Filho for being our liaison with the Somerville Housing Authority. We also thank the volunteers for their participation in the study. The study is funded by HUD (MALHH0194-09 to the City of Somerville). Brugge, Reisner, and Durant were also supported by NIEHS (ES015462 to Tufts University). Air Innovations provided the HEPA units, John Spengler provided the 3781 CPCs. Students that helped install/uninstall the equipment were Alex Bob, Daniel Chen, Brianna Cilley, Kyle Donahue, Dana Harada, Ashton Imlay, Piers MacNaughton, Allison Patton, Jessica Perkins, Andrew Shapero and Eric Wilburn.

References

- 1.US EPA. Quantitative Health Risk Assessment for Particulate Matter, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Health and Environmental Impacts Division. North Carolina: Research Triangle Park; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US EPA. The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act from 1990 to 2020, Final report, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Health and Environmental Impacts Division. North Carolina: Research Triangle Park; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US OMB. Executive office of the President of the United States. Washington, DC: 2011. 2011 report to congress on the benefits and costs of federal regulations and unfunded mandates on state, local, and tribal entities. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karner AA, Eisinger DS, Niemeier DA. Near-Roadway Air Quality: Synthesizing the Findings from Real-World Data. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(14):5334–5344. doi: 10.1021/es100008x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugge D, Durant JL, Rioux C. Near-highway pollutants in motor vehicle exhaust: A review of epidemiologic evidence of cardiac and pulmonary health risks. Environ Health. 2007;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rioux CL, Tucker KL, Mwamburi M, Gute DM, Cohen SA, Brugge D. Residential traffic exposure, pulse pressure, and C-reactive protein: consistency and contrast among exposure characterization methods. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:803–811. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams LA, Ulrich CM, Larson T, Wener MH, Wood B, Campbell P, Potter J, McTiernan A, De Roos A. Proximity to traffic, inflammation, and immune function among women in the Seattle, Washington, area. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(3):374–378. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Dragano N, Stang A, Möhlenkamp S, Schmermund A, Memmesheirmer M, Brocker-Preuss M, Mann K, Erbel R, Jockel K. Chronic residential exposure to particulate matter air pollution and systemic inflammatory markers. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1302–1308. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Möhlenkamp S, Stang A, Lehmann N, Dragano N, Schmermund A, Memmesheimer M, Mann K, Erbel R, Jöckel K. Residential exposure to traffic is associated with coronary atherosclerosis. Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigative Group. 2007;116:489–496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gan WQ, Tamburic L, Davies HW, Demers PA, Koehoorn M, Brauer M. Changes in residential proximity to road traffic and the risk of death from coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2010;21:642–649. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89f19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batterman S, Godwin C, Jia C. Long duration tests of room air filters in cigarette smokers’ homes. Environ Sci and Tech. 2005;39(18):7260–7268. doi: 10.1021/es048951q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batterman S, Du L, Mentz G, Mukherjee B, Parker E, Godwin C, et al. Particulate Matter Concentrations in Residences: An Intervention Study Evaluating Stand-Alone Filters and Air Conditioners. Indoor Air. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2011.00761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du L, Batterman S, Parker E, Godwin C, Chin J-Y, O’Toole A, et al. Particle concentrations and effectiveness of free-standing air filters in bedrooms of children with asthma in Detroit, Michigan. Build Environ. 2011;46(11):2303–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, Raja S, Ferro AF, Jaques PA, Hopke PK, Gressani C, et al. Effectiveness of heating, ventilation and air conditioning system with HEPA filter unit on indoor air quality and asthmatic children’s health. Build Environ. 2010;45(2):330–337. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanphear BP, Hornung RW, Khoury J, Yolton K, Lierl M, Kalkbrenner A. Effects of HEPA Air Cleaners on Unscheduled Asthma Visits and Asthma Symptoms for Children Exposed to Secondhand Tobacco Smoke. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):93–101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bräuner EV, Møller P, Barregard L, Dragsted LO, Glasius M, Wåhlin P, et al. Exposure to ambient concentrations of particulate air pollution does not influence vascular function or inflammatory pathways in young healthy individuals. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008a;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bräuner EV, Forchhammer L, Møller P, Barregard L, Gunnarsen L, Afshari A, Wåhlin P, et al. Indoor particles affect vascular function in the aged: an air filtration-based intervention study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008b;177(4):419–425. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-632OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen RW, Carlsten C, Karlen B, Leckie S, van Eeden S, Vedal S, et al. An air filter intervention study of endotelial function among healthy adults in a woodsmoke-impacted community. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(9):1222–1230. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1572OC. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scammell MK, Duro L, Litonjua E, Berry L, Reid M. Meeting People Where They Are: Engaging Public Housing Residents for Integrated Pest Management. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5:177–182. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rorie JA, Smith A, Evans T, Horsburgh CR, Jr, Brooks DR, Goodman R, et al. Using resident health advocates to improve public health screening and follow-up among public housing residents, Boston, 2007–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(1):A15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy JI, Brugge D, Peters JL, Clougherty JE, Saddler SS. A community-based participatory research study of multifaceted in-home environmental interventions for pediatric asthmatics in public housing. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2191–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krieger J, Takaro TK, Allen C, Song L, Weaver M, Chai S, et al. The Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project: Implementation of a comprehensive approach to improving indoor environmental quality for low-income children with asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:311–322. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemphill Fuller C, Reisner E, Meglio D, Brugge D. Challenges of using community-based participatory research to research and solve environmental problems. In: Harter LM, Hamel-Lambert J, Millesen J, editors. Participatory partnerships for social action and research. 2011. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durant JL, Ash CA, Wood EC, Herndon SC, Jayne JT, Knighton WB. Short-term variation in near-highway air pollutant gradients on a winter morning. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:8341–8352. doi: 10.5194/acpd-10-5599-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hertel S, Viehmann A, Moebus S, Mann K, Bröcker-Preuss M, Mohlenkamp S, et al. Influence of short-term exposure to ultrafine and fine particles on systemic inflammation. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(8):581–592. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Polidori A, Arhami M, Gillen DL. Circulating Biomarkers of Inflammation, Antioxidant Activity, and Platelet Activation Are Associated with Primary Combustion Aerosols in Subjects with Coronary Artery Disease . Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(7):898–906. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brugge D, Melly S, Finkelman A, Russell M, Bradeen L, Perez R, et al. A community-based participatory survey of public housing conditions and associations between renovations and possible building-related symptoms. Appl Environ Sci Public Health. 2003;1:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brugge D, Kapunan P, Babcock-Dunning L, Matloff R, Cagua-Koo D, Okoroh E, et al. Developing methods to compare low-education community-based and university-based survey teams. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(5):645–653. doi: 10.1177/1524839908329120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker AB, Israel BA, Allen AJ., III . Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. In: Isreal BA, et al., editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owens JS, Andrews N, Collins J, Griffeth JC, Mahoney MA. Finding common ground: University research guided by community needs for elementary school-aged youth. In: Harter LM, Hamel-Lambert J, Millesen JL, editors. Participatory partnerships for social action and research. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews JO, Tingen MS, Jarriel SC, Caleb M, Simmons A, Brunson J, Meuller M, Ahluwalia JS, Newman SD, Cox MJ, Magwood G, Hurman C. Application of a CBPR framework to inform a multi-level tobacco cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods. Am J Commun Psychol. 2012;50:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]