Abstract

Objective

The objective was to test the hypothesis that heart failure (HF) patients treated with sertraline will have lower depression scores and fewer cardiovascular events compared to placebo.

Background

Depression is common among HF patients. It is associated with increased hospitalization and mortality.

Methods

SADHART-CHF was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline 50 to 200 mg/day versus matching placebo for 12 weeks. All participants also received nurse facilitated support. Eligible patients were age ≥45 years with HF (LVEF ≤45%, NYHA class II-IV) and clinical depression (DSM-IV criteria for current major depressive disorder). Significant cognitive impairment, psychosis, recent alcohol or drug dependence, bipolar or severe personality disorder, active suicidal ideation, and current antipsychotic or antidepressant medications were exclusions. Primary endpoints were change in depression severity (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS] total score) and composite cardiovascular status at12-weeks.

Results

469 patients were randomized (N=234 sertraline, N=235 placebo). The mean ± SE change from baseline to 12-weeks in the HDRS total score was -7.1 ± 0.5 (sertraline) and -6.8 ± 0.5 (placebo) (P<.001 from baseline, P=.89 between groups, mean change between groups -0.4, 95% CI -1.7, 0.92). The proportion whose composite cardiovascular score worsened, improved, or was unchanged was 29.9%, 40.6%, and 29.5% in the sertraline group and 31.1%, 43.8%, and 25.1% in the placebo group (P=0.78).

Discussion

Sertraline was safe in patients with significant HF. However, treatment with sertraline compared with placebo did not provide greater reduction in depression or improved cardiovascular status among patients with HF and depression.

Keywords: heart failure, depression

Introduction

Heart failure is prevalent in both the United States and Europe. An estimated 5.7 million Americans have heart failure (1), and there are at least 15 million patients with heart failure in the 51 countries represented by the European Society of Cardiology (2). Heart failure is a major cause of death and disability. Despite extensive therapeutic advances in pharmacologic and device therapies for heart failure, morbidity and mortality remain high in this population (3).

Depression is common in heart failure, with a reported prevalence of 21.5% (4), and it is one of many factors that contribute to poor outcome in heart failure patients (5-8). Depression has been independently associated with a poor quality of life, limited functional status, and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in this population (4;9-13).

Small studies have demonstrated improvements in depressive symptoms and quality of life, and reductions in heart rate and plasma norepinephrine for heart failure patients treated with antidepressants (14;15). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to inhibit platelet function, promote endothelial stabilization, and possess anti-inflammatory properties, although the clinical relevance of these properties have yet to be established (16-24). These pharmacologic properties have led to the hypothesis that SSRIs may be associated with cardiovascular benefits beyond their antidepressant effects. SSRIs have been shown to improve depression scores without adverse cardiovascular effects in several studies conducted in patients with acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or stable coronary artery disease (25;26). These data suggested the safety profile of sertraline was adequate to permit testing in the heart failure population. The objective of the SADHART-CHF (Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in CHF) study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of sertraline in patients with depression and heart failure.

Methods

The SADHART-CHF trial was a randomized, double-blind trial of sertraline or placebo in 469 participants with heart failure and clinical depression. The study was conducted at 3 centers in the United States between 8/13/2003 and 3/3/2008. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review board for each center. All participants provided written, voluntary informed consent.

Eligibility Criteria

A complete description of the trial methodology has been published (27). Briefly, patients ≥45 years of age with LVEF ≤45% (within the previous 6 months), NYHA class II-IV heart failure symptoms, and major depressive disorder (as determined by DSM-IV criteria) were eligible for participation. Heart failure was confirmed at the time of presentation by clinical heart failure specialist cardiologists. The main exclusion criteria included significant cognitive impairment, alcohol or drug dependence within the previous year, psychoses, bipolar disorder, severe personality disorder, active suicidal ideation, life-threatening comorbidity (estimated 50% mortality within 1 year), and current use of antipsychotic or antidepressant medications.

Study Design

SADHART-CHF tested the hypothesis that sertraline would improve symptoms of depression and reduce cardiac events and morbidity/mortality in heart failure patients with clinical depression to a greater extent than placebo. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to sertraline or matching placebo for the 12-week treatment period. The initial dose was 50 mg/day, and was increased in 50 mg/day increments based on the results of the BDI total score and the clinical opinion of the examining investigator to a maximum of 200 mg/day. For patients who were unable to tolerate higher doses, the dose could be decreased. The minimum dose was 50 mg/day. Participants were categorized as completers if they completed 12-weeks of study drug and assessment at the end of the 12-week intervention, and non-completers if they discontinued study drug prior to 12-weeks. All participants, regardless of whether or not they completed the 12-week treatment period were included in all analyses as described in the statistical analysis section.

All participants also received nurse facilitated support, designed to build rapport and trust with the study participants, ascertain compliance with the study protocol, re-evaluate depression status, monitor suicidal ideation, and consult with study physicians on appropriate patient management. Support was provided by nurses and other study personnel with prior experience or training in clinical psychiatry, and they conducted interviews with the study participants by telephone at 2, 4, 8, and 10 weeks and during in-clinic or home visits at 6 and 12 weeks. Participants were also screened for suicidal ideation. The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was completed at baseline and at 2 week intervals during the 12-week treatment phase.

All participants were referred to their primary care physician or a psychiatrist for follow-up as indicated after the initial 12-week period. All participants were followed via phone or mail to ascertain clinical events and vital status every 2 weeks during the 12 week treatment phase and at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter until the last participant completed at least 6-months of follow-up. The national death index was used to ascertain vital status of participants who could not be reached via phone or mail.

Primary Endpoints

The primary endpoints of the study were change across time in the severity of depression (measured by the HDRS total score) and composite cardiovascular status (Table 1), both assessed at the end of the 12-week treatment period. Cardiovascular events and survival during the short-term treatment phase and long-term follow-up were also assessed.

Table 1. Composite Cardiovascular Score.

| Status | Definition |

|---|---|

| Worsened | Any of the following conditions occur after randomization

|

| Improved | The criteria for “worsened” has not been previously met AND at least one of the following conditions occurred at the last assessment completed during the post-randomization period:

|

| Unchanged | Participant is neither improved or worsened |

Adjudication of Cardiovascular Events

All cardiovascular events were adjudicated by three cardiologists with a heart failure sub-specialty who were blinded to treatment assignment. All cardiovascular events resulting in a procedure or hospitalization were adjudicated according to a pre-defined set of criteria. Each event was reviewed by committee members separately and discussed during face-to-face meetings. Discrepancies among reviewers were presented and discussed to achieve consensus for all events.

Statistical Analysis

The study was designed to have at least 80% power to detect true between group differences at the end of the 12-week treatment phase. A target enrollment of 500 was proposed during the design stages based on estimates of: (a) 3-month cardiovascular mortality and re-admission rates and (b) 3-month treatment response rate for depression. Based on published findings, we predicted that the composite cardiovascular worsening rate would be 35% in the sertraline group and 50% in the placebo group. Power calculations indicated that a sample size of 440 (220 per treatment arm) would yield 80% power to detect a treatment difference for the expected rates of the primary cardiovascular endpoint when applying a two-sided, continuity-corrected chi-square test with the level of significance set at 0.05. The depression literature suggested a response rate of 70-75% for sertraline and a placebo response rate as high as 50%. A sample size of 200 (100 per treatment arm) would yield at least 80% power to detect a treatment difference for expected response rates of 70% and 50% when using a two-sided, continuity-corrected chi-square test with the level of significance set at 0.05. The primary depression outcome was the continuous HDRS total scores collected over time rather than a dichotomized response score. The primary analysis of this measure was a longitudinal analysis using a random coefficients regression model. During the design stages, sufficient data were not available to estimate the treatment-by-time effects for heart failure patients, so the sample size was based on estimated response rate. It should be noted that continuous measures and longitudinal analysis methods often provide greater power than chi-square analyses designed to test for differences in binary outcomes. Thus, we concluded that a sample size of 440 would provide 80% or greater power for two primary outcomes. The target enrollment was increased to 500 to adjust for early termination.

Statistical analyses were performed by statistical personnel within Duke University Medical Center, using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Incorporated, Cary, NC). The primary analysis was conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle. Although some participants did not complete 12-weeks of treatment, all participants, regardless of whether or not they completed 12-weeks of treatment, were included in all analyses. The complete analytic methods have previously been described (27). Briefly, linear random coefficients regression models adjusting for the effects of clinical site were used as a longitudinal data analysis method to examine the trajectory of change in HDRS total scores over the acute 12 week treatment period between the two treatment arms. This methodology allows all participants with data for at least one time point to be included (n=469) and eliminates the issue of dealing with missing data. This hierarchical mixed model included the fixed effects of treatment, the natural log of time and natural log of time squared, their interactions with treatment, and site, as well as the random effects of patient, patient-by-time, and square of patient-by-time. Tests for differences of proportions were used to examine the composite cardiovascular status outcome at the end of acute treatment. Chi-square tests were used to test for overall treatment differences, with a Mantel-Haenszel test performed to examine treatment differences when controlling for clinical site. The primary analyses were conducted on the tri-level cardiovascular status outcome.

A per-protocol analysis was also performed. This analysis included only those participants who completed 12-weeks of treatment (n=290), and it was conducted on the change in HDRS over the 12 week period and on the composite cardiovascular status. The analyses were similar to those conducted on the intention-to-treat sample.

Role of the Funding Source

The SADHART-CHF study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Bethesda, Maryland. The NIMH did not participate in study development, conduct, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the study report. The NIMH was given an opportunity to review the manuscript prior to submission, but they did not participate in the decision to submit for publication. Sertraline was supplied by Pfizer, Inc., New York, New York. Pfizer had no other role in any aspect of the study.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 469 participants were enrolled, and their flow through the trial is shown in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population by treatment group are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. Participant Flow Through the Trial.

Completers were participants who completed 12-weeks of study drug and assessment at the end of the 12-week intervention. Non-completers were participants who discontinued study drug prior to 12-weeks. Participants were considered non-compliant if they did not take the study medication for ≥14 consecutive days.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics.

| Sertraline N=234 |

Placebo N=235 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.9 (10.5) | 61.4 (11.1) |

| Women, No. (%) | 101 (43.2) | 89 (37.9) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 131 (56) | 136 (57.9) |

| African American | 92 (39.3) | 82 (34.9) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 2 (0.9) |

| Heart Failure Characteristics | ||

| NYHA Class, No. (%) | ||

| I | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| II | 71 (30.3) | 61 (26) |

| III | 109 (46.6) | 114 (48.5) |

| IV | 54 (23.1) | 60 (25.5) |

| LVEF, mean (SD) | 31.3 (9.5) | 29.5 (10.1) |

| Ischemic etiology, No. (%) | 163 (69.7) | 163 (69.4) |

| ≥1 heart failure hospitalization in previous 12 months, No. (%)* | 134 (57.3) | 158 (67.2) |

| Depression Characteristics | ||

| BDI Total Score, mean (SD) | 19.9 (7.2) | 18.4 (6.6) |

| HDRS Total Score, mean (SD) | 18.3 (5.5) | 18.3 (5.4) |

| Depression History | ||

| Antidepressant Use at Recruitment, No. (%) | 19 (8.1) | 15 (6.4) |

| Major depression, No. (%) | 39 (16.7) | 25 (20.6) |

| Cardiovascular History | ||

| Coronary artery disease, No. (%) | 172 (73.5) | 159 (67.7) |

| Myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 122 (52.1) | 105 (44.7) |

| Arrhythmia, No. (%) | 94 (40.2) | 106 (45.1) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 212 (90.6) | 200 (85.1) |

| Hyperlipidemia, No. (%) | 180 (76.9) | 183 (77.9) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 126 (53.8) | 108 (46) |

| Renal disease, No. (%) | 81 (34.6) | 87 (37) |

| PCI/Stent, No. (%) | 83 (35.5) | 88 (37.4) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, No. (%) | 82 (35) | 78 (33.2) |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, No. (%) | 45 (19.2) | 45 (19.1) |

| Permanent pacemaker, No. (%) | 17 (7.3) | 12 (5.1) |

| Cardiovascular Medications | ||

| ACE-inhibitor, No. (%) | 165 (71.4) | 165 (70.2) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, No. (%) | 22 (9.4) | 17 (7.2) |

| Beta blocker, No. (%) | 202 (86.3) | 194 (82.6) |

| Loop diuretic, No. (%) | 144 (61.5) | 147 (62.6) |

| Digoxin, No. (%) | 36 (15.4) | 44 (18.7) |

| Statin, No. (%) | 168 (71.8) | 158 (67.2) |

| Aspirin, No. (%) | 197 (84.2) | 194 (82.6) |

P=.03

Study Drug Treatment and Discontinuation

A total of 234 participants were randomized to sertraline. Of these, 138 were classified as completers. The mean ± SD number of days treated was 86.1 ± 5.7. The remaining 96 participants (non-completers) received study drug for a mean ± SD of 36.7 ± 26.2 days. The mean last dose of sertraline was 65 ± 29 mg/day achieved in those completing 12-weeks of treatment, and 63 ± 29 mg/day in those who did not. In the placebo group, 152 participants of the 235 randomized completed the 12-week treatment period and received study drug for 86.2 ± 5.3 days (mean ± SD). The remaining 83 participants were non-completers and stopped study drug after 34.7 ± 26.1 days of treatment. The mean dose of matching placebo was 92 ± 52 mg/day achieved in those completing 12-weeks of treatment, and 67 ± 35 mg/day in those who were non-completers. The reasons for study drug withdrawal are given in Figure 1.

12-Week Acute Phase Endpoint

HDRS Total Score

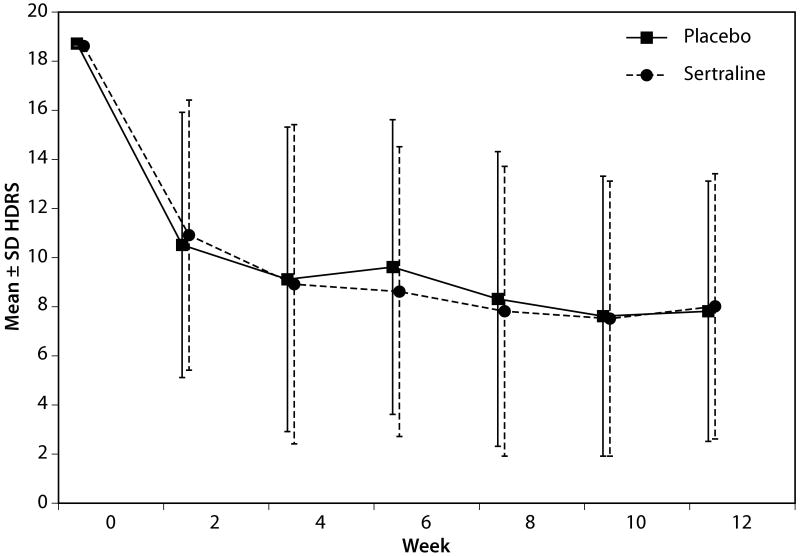

The mean ± SD HDRS total score at baseline was 18.3 ± 5.5 in the sertraline group and 18.3 ± 5.4 in the placebo group. Figure 2 displays the trajectory of improvement in the raw total scores of HDRS across the treatment phase. Both groups exhibited a significant reduction in the HDRS total score (time P<.001; time squared P<.001), but this reduction in HDRS total score was not significantly different between groups (mean change -0.4, 95% CI -1.7-0.9, treatment-by-time interaction, P=.89; treatment-by-time squared interaction P=0.76). The mean ± SE change from baseline to 12-weeks was -7.1 ± 0.5 and -6.8 ± 0.5 in the sertraline and placebo groups, respectively.

Figure 2. Change in HDRS from Baseline to Week 12.

Based on raw HDRS scores. This plot displays the change in HDRS total scores by week in the study. The primary analysis was conducted based on the natural log of days, with a P=.89.

A total of 8.8% of patients were titrated up to 200mg/day, 9.0% to 150mg/day, 20.6% to 100mg/day, and 61.7% were maintained at 50mg/day. The HDRS scores at baseline vs. 12-weeks for all the completers among these four groups were as follows: 21.0 vs. 15.6 (200 mg/day); 20.2 vs. 9.9 (150 mg/day); 18.2 vs. 7.6 (100 mg/day); and 17.6 vs. 4.4 (50 mg/day). There was no treatment assignment by dose interaction, p=0.281.

A longitudinal analysis of HDRS was performed in the subgroup of 64 participants with a history of depression and a HDRS score >17 at baseline. The results were similar to the intention-to-treat analysis. The mean change in HDRS from baseline to 12-weeks was -6.2 (P=0.002) in the sertraline group and -5 (P=0.001) in the placebo group. There was no difference in change scores between groups (1.3, 95% CI -3.5, 6.1; P=0.59). Again, there was no treatment by dose interaction.

Composite Cardiovascular Status

In the sertraline group, the composite cardiovascular status worsened in 29.9% (70/234), improved in 40.6% (95/234), and remained unchanged in 29.5% (69/234). In the placebo group, 31.1% (73/235) worsened, 43.8% (103/235) improved, and 25.1% (59/235) were unchanged. The proportion of participants classified as worsened, improved, or unchanged did not differ significantly between groups (P=.78).

The 12-week mortality rate was 7% in the overall population. No differences were observed between groups in individual components of the composite score, including all cause mortality, cardiovascular death, non-fatal cardiovascular events, heart failure hospitalization, or combinations of these outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3. Fatal and Non-Fatal Events Through 12-Weeks.

| Event | Sertraline N=234 |

Placebo N=235 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause mortality, No. (%) | 18 (7.7) | 15 (6.8) | .58 | |

| Cardiovascular death, No. (%) | 16 (6.8) | 10 (4.3) | .59 | |

| Non-fatal cardiovascular event, No. (%) | 47 (20.1) | 55 (23) | .39 | |

| Acute myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | .31 | |

| Arrhythmia, No. (%) | 4 (1.7) | 6 (2.6) | .53 | |

| Cardiac syncope, No., (%) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | .32 | |

| Cerebrovascular accident, No. (%) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | .56 | |

| Exacerbation of heart failure, No. (%) | 19 (8.1) | 30 (12.8) | .1 | |

| Unstable angina, No. (%) | 7 (3) | 5 (2.1) | .55 | |

| Other non-fatal cardiovascular event, No. (%) | 14 (6) | 12 (5.1) | .68 | |

| All cause mortality or non-fatal cardiovascular event, No. (%) | 65 (29.4) | 70 (29.8) | .63 | |

| Heart failure hospitalization or death, No. (%) | 37 (15.8) | 45 (19.2) | .34 | |

The total number of days alive during the 12-week acute phase was similar in both groups, 86.1 ± 15.7 in the sertraline group, and 86.2 ± 15.4 in the placebo group (P=.61). The distribution of change in NYHA class was also similar among groups. NYHA class worsened in 61 (34.9%) of the sertraline group and 73 (41%) of the placebo group, and it was unchanged or improved in 114 (65.1%) of the sertraline group and 105 (59%) of the placebo group.

An as per-protocol analysis (including only those participants who completed 12-weeks of treatment) was also performed. The results for change in HDRS and composite cardiovascular score were similar to the findings of the intention-to-treat analysis.

Tolerability and Safety

A significantly higher proportion of participants in the sertraline arm withdrew from the treatment phase because of side effects that were believed to be study drug related (N=27/234; 11.5%) as compared to the placebo group (N=14/235; 6.0%) (P=.03). Nausea (9/41 [21.9%] vs. 1/41 [2.4%]) and dizziness (4/41 [9.8%] vs. 2/41 [4.9%]) were the most common side effects reported with a higher frequency in the sertraline arm. Serious adverse events were not statistically different between the groups (Table 4). Two participants in the placebo group developed significant suicidal ideations during the acute treatment phase. There were no suicide attempts or completed suicides.

Table 4. Serious Adverse Events by Treatment Group at 12 weeks.

| SAE Type (N=194) |

Sertraline N=98 |

Placebo N=96 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular, No. (%) | 69 (35.6)* | 72 (37.1)* | .79 |

| Psychiatric† | 0 (0)* | 2 (1)* | .16 |

| Non-CV and Non-psychiatric | 29 (14.9)* | 22 (11.3)* | .30 |

Percentages are calculated from the total SAEs (using N=194 as the denominator)

No attempted or completed suicide

Long-term Follow-up Endpoints

Participants were followed for 798 ± 493 days (mean ± SD) during the long-term follow-up phase (sertraline group 788 ± 480 days, placebo group 808 ± 506 days, P=.68). All cause mortality was not different between groups. A total of 68 participants (29.1%) in the sertraline group died compared to 61 (26%) in the placebo group. In the Cox model adjusted for site, the hazard ratio for survival was not significantly different between the two treatment groups (HR 1.3, 95% CI 0.66-2.58; P=.45). Non-fatal cardiovascular events were also similar (Table 5).

Table 5. Non-Fatal Cardiovascular Events During Long-term Follow-up.

| Sertraline N=234 |

Placebo N=235 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 10 (4.3) | 8 (3.4) | .63 |

| Arrhythmia, No. (%) | 17 (7.3) | 20 (8.5) | .61 |

| Cardiac syncope, No., (%) | 6 (2.6) | 6 (2.6) | .99 |

| Cerebrovascular accident, No. (%) | 10 (4.3) | 4 (1.7) | .1 |

| Exacerbation of heart failure, No. (%) | 64 (27.4) | 68 (28.9) | .7 |

| Unstable angina, No. (%) | 23 (9.8) | 19 (8.1) | .51 |

| *Other cardiovascular event, No. (%) | 50 (21.4) | 59 (25.1) | .34 |

Includes: wound infection, peripheral vascular disease, acute renal failure, drainage drive line, hypertensive urgency, presyncope, accelerated hypotension, hypotension, deep vein thrombosis, prerenal azotemia, graft thrombosis, non-unstable angina chest pain.

Discussion

All participants in SADHART-CHF demonstrated improvements in depression scores from baseline. Multiple reasons may be responsible for the lack of an observed additive benefit with sertraline. Placebo effects are common in anti-depressant trials. One analysis of 75 anti-depressant trials found a 30% placebo response rate, defined as the number of placebo treated patients who had a ≥50% reduction in the HDRS score (28). The placebo response in this study may have been enhanced by the nursing support provided to all participants. An additive benefit for sertraline on depression scores was not detected. It is possible that the close cardiovascular follow-up coupled with the nursing staff interactions improved mood disorders to a degree sufficient to blunt any sertraline effect. It is also possible that the mechanism of depression and mood disorders differs in the heart failure population, such that their response to traditional anti-depressant pharmacotherapy is inadequate.

The level of depression in our study may not have been severe enough to respond to sertraline therapy. A recent meta-analysis suggests that antidepressants may have minimal effect among patients with HDRS scores <23; the baseline HDRS scores in SADHART-CHF were 19.9 and 18.4 in the sertraline and placebo groups, respectively (29).

The mean doses of sertraline achieved in SADHART-CHF may have been insufficient to demonstrate efficacy. Additionally, the pharmacokinetics of many drugs may be altered in the setting of acute decompensation; it is possible that higher doses of sertraline may be needed in patients with a recent episode of acute decompensated heart failure to overcome the lower absorption that can occur in states of significant volume overload or reduced cardiac output (and decreased gastrointestinal perfusion) states. There are no data evaluating the extent to which sertraline pharmacokinetics may be altered in acute heart failure, but this hypothesis may be worth exploring in future studies.

Similarly, in the SADHART trial of sertraline in patients with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina, sertraline's overall effect size on the depression endpoint was small and only significant in the subset of patients with recurrent depression (25). These findings may reflect a true lack of efficacy for sertraline in these populations whose depression may not be severe enough to benefit from sertraline or other antidepressants (29). The pathophysiology of depression in patients with heart failure or acute myocardial infarction/unstable angina patients may have unique characteristics that may be less responsive to antidepressant therapy.

These data indicate that heart failure patients with evidence of depression may benefit from psychosocial supportive care delivered by clinically experienced personnel. Based on the findings of SADHART-CHF, there is no conclusive evidence that antidepressants provide additional benefit to supportive care in these patients. The use of antidepressant agents should likely be reserved for patients who do not respond to supportive care.

The SADHART-CHF study confirmed that patients with depression and heart failure remain at high risk of adverse outcome, with a mortality rate of 7% at 12 weeks. This high event rate is not an isolated finding; we have previously reported a 13% mortality rate at 12-weeks in a cohort of heart failure patients with major depression (30). This mortality rate is higher than would be expected based on the population's heart failure characteristics alone, considering the annual mortality rate reported in a similar outpatient heart failure population with primarily NYHA class II and III symptoms was 8.1-8.8% (31). The SADHART-CHF mortality rate is similar to the 60-90 day post-discharge mortality rate of 8.6% reported in patients hospitalized for heart failure in the OPTIMIZE-HF registry (32). This elevated short-term mortality rate may be due to the presence of depression, and it reinforces the need to find more effective treatment and management approaches for depression in patients with heart failure.

Sertraline did not influence short or long-term cardiovascular events or survival in this study as compared to the placebo. The proportion of participants whose cardiovascular status worsened, improved, or was unchanged was similar among treatment groups. Fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events were also similar between groups. Thus, the ancillary properties of SSRIs (16-24) did not translate into cardiovascular benefit, at least in this short-term study.

A large, ongoing trial will provide further evidence to guide the management of patients with heart failure and depression (18). The Morbidity, Mortality and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure patients (MOOD-HF) study plans to randomize 700 patients to escitalopram 10-20 mg/day or placebo for 12-24 months. The primary endpoint is the time to first death or hospitalization (18). The results are expected in fourth quarter 2010 (source: http://isrctn.org, registry number 33128015).

The SADHART-CHF results should be evaluated in the context of several limitations. Nurse support may have contributed to the placebo response and improvement in depression scores, limiting the ability to detect a difference between groups. The non-completer rate was approximately twice the rate assumed in the sample size calculations. However, even a larger sample would be unlikely to affect the results, given the small observed differences between groups. Finally, a short-term duration of therapy may have been insufficient to fully demonstrate the potential effects of sertraline on cardiovascular outcomes.

In conclusion, depression in patients with heart failure is associated with substantial mortality. Sertraline did not adversely affect cardiovascular outcomes in this population, and it may be an appropriate therapeutic strategy in patients who remain depressed despite non-pharmacologic interventions and who otherwise have an indication for sertraline. Many patients with depression and heart failure who have coronary heart disease may be candidates for depression treatment on the basis of their coronary heart disease alone (33). Further research is needed to determine the optimal combination of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment of depression in patients with heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The SADHART-CHF study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Bethesda, Maryland. Sertraline was supplied by Pfizer, Inc., New York, New York. Pfizer had no other role in any aspect of the study.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- HDRS

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- HR

hazard ratio

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MOOD-HF

Morbidity, Mortality and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure patients

- NIMH

National Institutes of Mental Health

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- SADHART – CHF

Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in CHF

- SSRI

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Footnotes

- Dr. Jiang received salary support through the NIMH research grant, and she has received funding from Pfizer, Inc. to study non-pharmacologic intervention on depression improvement and the effects of Pregabalin on the autonomic nervous system of patients with diabetes.

- Dr. O'Connor has received grants or research funding from Pfizer, Inc, and he received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Silva receives honoraria from Pfizer, Inc. related to work as a DSMB member, providing DSMB oversight of 4 pediatric mental health trials that do not involve sertraline, the medication studied in SADHART-CHF. Dr. Silva also received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Kuchibhatla received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Cuffe is a consultant to Novartis and GSK, and he receives honoraria from Novartis and GSK. He also received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Callwood (Callwood Cardiology) received received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Zakhary: Nothing to disclose

- Dr. Stough: Nothing to disclose

- Ms. Arias received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Rivelli received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

- Dr. Krishnan is a consultant to Amgen, Bristol-Myer Squibb, CeNeRx, Corcept, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Organon, Pfizer, Sepracor, Wyeth, and he received salary support through the NIMH research grant.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: NCT00078286 (clinicaltrials.gov)

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2009 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388–442. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–e235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy WC, Linker DT. Prediction of mortality in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2008;10:198–205. doi: 10.1007/s11886-008-0034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan MD, Levy WC, Crane BA, Russo JE, Spertus JA. Usefulness of depression to predict time to combined end point of transplant or death for outpatients with advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1577–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Clary GL, et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson P, Dahlstrom U, Alehagen U. Depressive symptoms and six-year cardiovascular mortality in elderly patients with and without heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2007;41:299–307. doi: 10.1080/14017430701534829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller-Tasch T, Peters-Klimm F, Schellberg D, et al. Depression is a major determinant of quality of life in patients with chronic systolic heart failure in general practice. J Card Fail. 2007;13:818–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Antidepressant use, depression, and survival in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2232–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottlieb SS, Kop WJ, Ellis SJ, et al. Relation of depression to severity of illness in heart failure (from Heart Failure And a Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training [HF-ACTION]) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1285–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottlieb SS, Kop WJ, Thomas SA, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of controlled-release paroxetine on depression and quality of life in chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;153:868–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Laliberte MA, et al. An open-label study of nefazodone treatment of major depression in patients with congestive heart failure. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:695–701. doi: 10.1177/070674370304801009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, et al. Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: the Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet Substudy. Circulation. 2003;108:939–44. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085163.21752.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziegelstein RC, Meuchel J, Kim TJ, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use by patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Med. 2007;120:525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Stork S, et al. Rationale and design of a randomised, controlled, multicenter trial investigating the effects of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibition on morbidity, mortality and mood in depressed heart failure patients (MOOD-HF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:1212–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurbel PA, Gattis WA, Fuzaylov SF, et al. Evaluation of platelets in heart failure: is platelet activity related to etiology, functional class, or clinical outcomes? Am Heart J. 2002;143:1068–75. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.121261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair GV, Gurbel PA, O'Connor CM, Gattis WA, Murugesan SR, Serebruany VL. Depression, coronary events, platelet inhibition, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:321–3. A8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serebruany VL, Murugesan SR, Pothula A, et al. Increased soluble platelet/endothelial cellular adhesion molecule-1 and osteonectin levels in patients with severe congestive heart failure. Independence of disease etiology, and antecedent aspirin therapy. Eur J Heart Fail. 1999;1:243–9. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(99)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serebruany VL, O'Connor CM, Gurbel PA. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelets in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:1398–400. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serebruany VL, Gurbel PA, O'Connor CM. Platelet inhibition by sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline: a possible missing link between depression, coronary events, and mortality benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:453–62. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors yield additional antiplatelet protection in patients with congestive heart failure treated with antecedent aspirin. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:517–21. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Koszycki D, et al. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. JAMA. 2007;297:367–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang W, O'Connor C, Silva SG, et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with CHF (SADHART-CHF): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline for major depression with congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2008;156:437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M. Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA. 2002;287:1840–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, et al. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet. 2003;362:759–66. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Influence of a performance-improvement initiative on quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: results of the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1493–502. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Jr, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]