Abstract

Background:

Studies show that patients are significantly less satisfied with torso scars than scars elsewhere. Though not an uncommon practice, it is unknown if application of adhesive tapes following dermatological surgery help improve cosmesis.

Objective:

To determine the effect of taping sutured torso wounds on overall scar appearance, scar width and patient satisfaction with the scar.

Patients/Methods:

Participants having elliptical torso skin excisions in a primary care setting in regional Australia were randomized in a single-blinded, controlled trial to 12 weeks taping (intervention) or usual care (control) following deep and subcuticular suturing. A blinded assessor reviewed scars at three and six months.

Results:

Of 195 participants recruited, 136 (63 taped, 73 controls) completed six months of follow-up. Independent blinded assessment of overall scar appearance was significantly better in taped participants (p= 0.004). Taping reduced median scar width by 1 mm (p=0.02) and when stratified by gender, by 3.0 mm in males (p=0.04) and 1.0 mm in females (p=0.2). High participant scar satisfaction was not further improved by taping.

Conclusion:

Taping elliptical torso wounds for 12 weeks after dermatologic surgery improved scar appearance at six months.

Keywords: taping, trunk, torso, scars, dermatologic surgery

Introduction

Dermal postoperative repair produces scar tissue that can cause significant psychological and physical consequences [1,2]. With an estimated 55 million elective operations occurring each year in the developed world alone [3] and confirmation that most patients (irrespective of age, gender and ethnicity) believe that even a small improvement in scarring is worthwhile [4], any research that may help improve scar outcome is meaningful.

Research has confirmed a positive correlation between tension and increased scar tissue formation [5,6]. The great range of movement afforded by the spine renders scars on the trunk particularly vulnerable to tension and subsequent disfigurement. It may therefore not be surprising that patients are significantly more dissatisfied with torso scars than other scars [7–9]. Dermatologic surgery on the trunk is common worldwide, and in Australia 27% of all basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), 8% of all squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), 25% of all invasive melanoma in men and 11% of all invasive melanoma in women are excised from the torso [10,11].

Evidence shows that prolonged use of adhesive tapes applied along a scar following surgery may reduce scar volume and improve cosmetic outcome [12,13]. Though short-term taping following dermatological surgery may be standard protocol for many practices, the optimal duration and mechanism of action of this intervention remains unclear [12,14].

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of 12 weeks of tape application perpendicular to sutured torso wounds on overall aesthetic appearance and width of the scars, as well as patient scar satisfaction at six months following surgery.

Materials and methods

This was a randomized controlled assessor blinded trial involving patients having elliptical skin excisions on the torso in a primary health care setting. The study was approved by the University of Queensland ethics committee (approval number #2008000535 April 2008). All patients gave written informed consent.

Setting & participants

Consecutive eligible patients were recruited by two general practitioners (including the principal researcher, HR), at a primary health skin cancer clinic in Townsville, North Queensland, Australia from June 2008 to January 2010.

Baseline demographic data, relevant medical history, degree of torso movement anticipated during the study period and lesion histology were documented (Table 1). Excision sites were recorded on body maps. The principal researcher trained staff to ensure consistency of data collection and standardization of management.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment group

| Characteristic | Control Group n=103 | Intervention group n=92 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years—mean (SD) | 52.6 | (15.4%) | 51.4 | (15.1%) | 0.59 |

| Women | 50 | (48.5%) | 56 | (60.9%) | 0.10 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) – mean (SD) | 27.0 | (4.1%) | 26.7 | (4.5%) | 0.61 |

| Diagnoses of diabetes | 8 | (7.8%) | 7 | (7.6%) | 0.97 |

| Prescribed aspirin, clopidogrel and/or inhaled steroids | 16 | (15.5%) | 9 | (9.8%) | 0.23 |

| Smoking status | 0.28 | ||||

| Ex-smoker | 33 | (32.0%) | 27 | (29.3%) | |

| Current smoker | 9 | (8.7%) | 15 | (16.3%) | |

| Level of activity at work | 0.28 | ||||

| Not working | 43 | (41.7%) | 32 | (34.8%) | |

| Sedentary occupation | 39 | (37.9%) | 30 | (32.6%) | |

| Moderate bending/ lifting | 12 | (11.7%) | 16 | (17.4%) | |

| Strenuous bending/ lifting | 9 | (8.7%) | 14 | (15.2%) | |

| Histology of skin lesion | 0.12 | ||||

| Basal cell carcinoma | 42 | (40.8%) | 44 | (47.8%) | |

| Sqamous cell carcinoma | 5 | (4.9%) | 9 | (9.8%) | |

| Cutaneous melanoma | 11 | (11.3%) | 6 | (6.5%) | |

| Dysplastic naevus | 34 | (32.0%) | 27 | (29.3%) | |

| Other naevus | 3 | (3.0%) | 5 | (5.4%) | |

| Other lesion | 8 | (7.8%) | 1 | (1.1%) | |

| Torso site | 0.27 | ||||

| Upper back (above waist) | 67 | (65.0%) | 59 | (64.2%) | |

| Lower back/buttock | 10 | (9.7%) | 11 | (11.9%) | |

| Chest | 22 | (21.4%) | 21 | (22.8%) | |

| Abdomen | 4 | (3.9%) | 1 | (1.1%) | |

| Median post-excision length of scar before suturing [mm] (IQR) | 33 | (25, 37) | 33 | (28, 37.5) | 0.41 |

| Median post-excision width of scar before suturing [mm] (IQR) | 19 | (15, 22) | 19 | (15, 22.5) | 0.72 |

IQR= inter-quartile range; SD = standard deviation

Moderate bending/ lifting <15kg (e.g. bowls/ gardening);

Strenuous bending/ lifting >15kg (e.g. rowing/ weight training)

The study nurse phoned participants within five days of surgery and then fortnightly for 12 weeks to ascertain analgesia requirements, wound complications and intervention compliance. Wound assessment was encouraged at three and six months even if participants had not been fully compliant with the intervention protocol.

Every participant gave signed informed consent and received written postoperative wound care information.

Eligibility criteria

Patients aged 18 to 80 years requiring elliptical skin excisions on the torso were eligible for the study provided they could easily reach the wound or had someone available to help with taping. Exclusion criteria included known tendency to keloid scarring; allergy to the sutures or skin tapes; flap surgery; and prescribed immunosuppressive drugs. Participants requiring a second wider excision for residual tumor or melanoma were subsequently excluded from the study.

Surgical wound management protocol

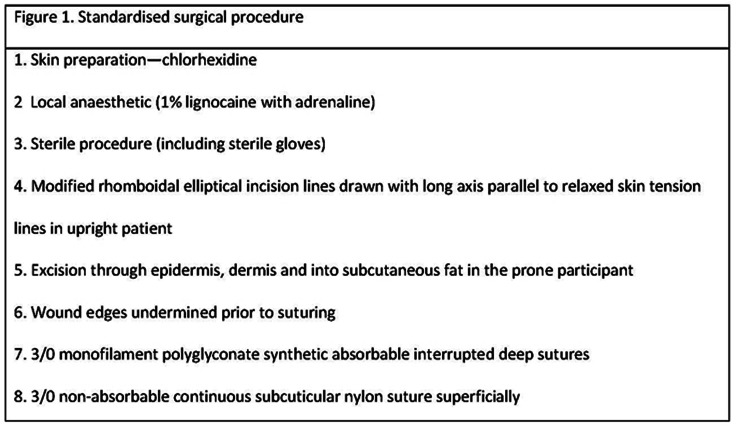

We used a standardized surgical procedure (Figure 1). In addition to deep and subcuticular sutures, an occasional superficial interrupted 3/0 nylon suture was used where necessary to improve wound edge apposition.

Figure 1.

Standardized surgical procedure. [Copyright: ©2013 Rosengren et al.]

Melolin dressings (Smith and Nephew Medical Ltd, Hull, UK), applied immediately after surgery, were changed after seven days (or sooner if soiled) and removed along with sutures 14 days postoperatively. A splash-proof dressing cover (Opsite Flexifix, Smith and Nephew Medical Ltd, Hull, UK) was used, making showering easier for participants. In the hotter more humid months (November to February inclusive), however, we used non-waterproof dressing covers (Fixomul Stretch, BSN Medical, Hamburg, Germany), allowing wounds to breathe better.

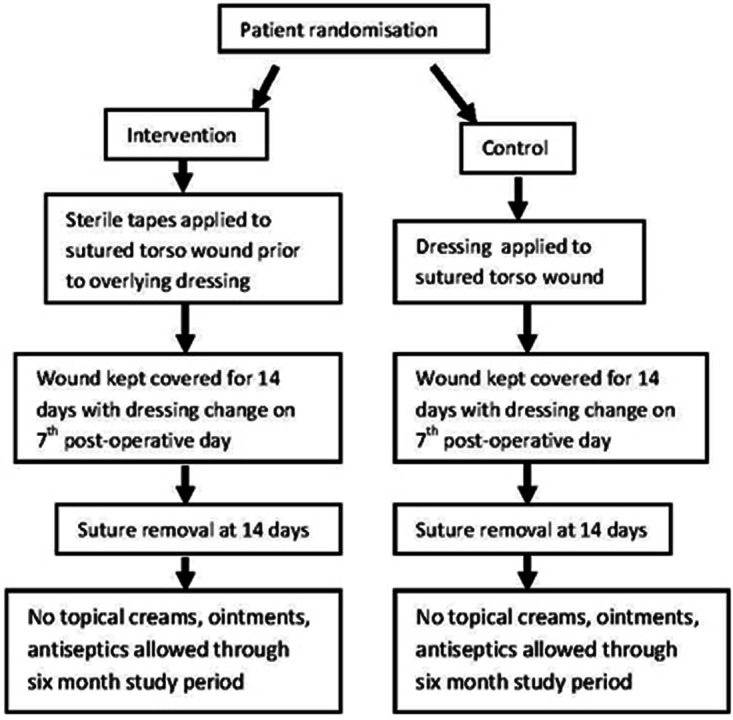

Intervention

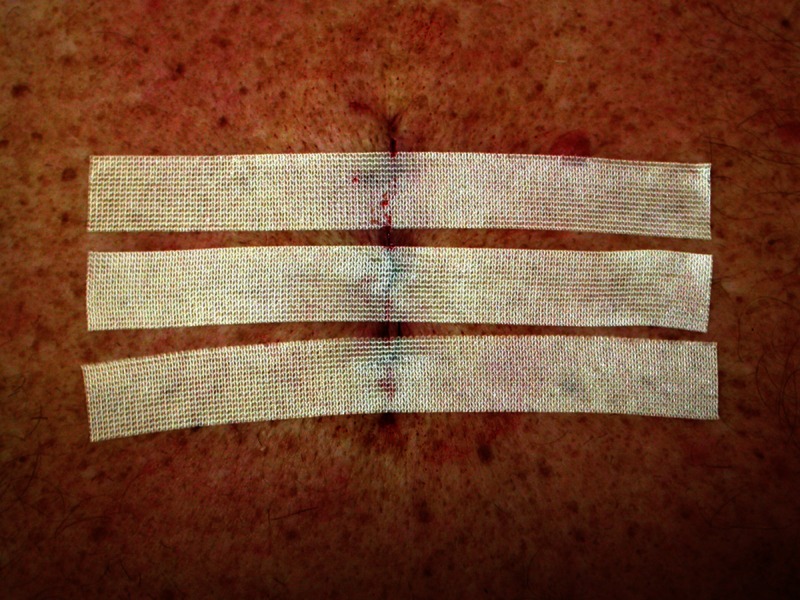

Adhesive tapes 100 mm long and 10 mm wide (Leukostrips, Smith and Nephew Medical Ltd, Hull, UK) were applied perpendicularly to the sutured wound, in parallel without overlapping, prior to the dressing (Figure 2). It has been shown that tapes adhere to skin for longer with this technique [15]. Participants and carers were shown how to apply and remove tapes as well as receiving written instructions and a descriptive photo of the taping technique (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Randomization protocol. [Copyright: ©2013 Rosengren et al.]

Figure 3.

Taped torso wound—a descriptive photo. [Copyright: ©2013 Rosengren et al.]

Instructions were given to change tapes on the same day each week for 12 consecutive weeks and to trim tape ends if they lifted. If no more than 4 cm extending either side of the scar, instructions were given to replace this tape and still change all tapes on the scheduled weekday.

Randomization and blinding

The allocation sequence was generated using a computerized randomization schedule at the Discipline of General Practice at The University of Queensland. Randomization was done in blocks of six to ensure roughly equal numbers in each study group. Sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes containing details of group allocation were only opened following wound closure to ensure blinding to randomization during the surgical procedure. Participants were asked not to reveal their group allocation to the blinded outcome assessor. Scars were assessed 10 to 14 days after completion of the 12-week intervention so that there was no residual tape adhesive that might inadvertently reveal group allocation. Outcome data entry was done at the University of Queensland by a research assistant not directly involved in the trial.

Clinical outcomes

Maximal scar width was recorded to the nearest millimeter. Overall scar appearance and participant satisfaction with their scar were both appraised using five-point categorical scales.

Outcome assessment was undertaken by an independent blinded research nurse three and six months postoperatively. Overall scar appearance was evaluated and documented along with presence of scar elevation, depression and dyschromia. Reference photographs taken and categorized by the principal investigator (HR) before commencement of the trial helped ensure consistency of this assessment.

Participants completed adapted questionnaires [16] at the assessment visits. Participant satisfaction with the scar was ascertained as well as how perceived cosmetic results compared to their expectation and whether they would use tapes for future torso scars if our study results proved favorable.

Sample size

It was hypothesized that a minimum mean difference of 2 mm in wound width between taped participants and controls would be clinically significant. To show this with statistical confidence (power in excess of 80%; significance level 0.05), 29 participants were required in each study group.

For overall scar appearance and patient scar satisfaction (both measured on categorical scales), it was hypothesized that a difference of at least one category between the two study groups would be clinically significant. To show this with statistical confidence (power in excess of 80%; significance level 0.05), 78 participants were required in each study group.

For all outcomes to be assessed and allowing for a 25% drop out rate, we planned to enroll 204 patients.

Statistical analysis

Participant data were analyzed according to allocated study group, irrespective of protocol violation or non-compliance. Success of randomization was ascertained by comparing baseline information between groups. This included age, gender, diabetes, smoking history, degree of torso movement at work and in leisure time, body mass index, histology of lesion, torso site and wound dimensions.

Numerical data were described using mean values and standard deviations when approximately normally distributed or median values and inter-quartile ranges when skewed. Chi-square tests, t-tests and non-parametric Wilcoxon tests were used for baseline comparisons between participants and non-participants and between the study groups. Wound assessments and patient satisfaction scores were compared using non-parametric Wilcoxon tests.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 18 (PASW; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline description of patients and skin lesions

Of 240 eligible patients, 195 opted to participate. Excisions were for skin cancer (44.1% BCCs, 7.2% SCCs) or suspicious pigmented lesions (48.7%) (Table 1).

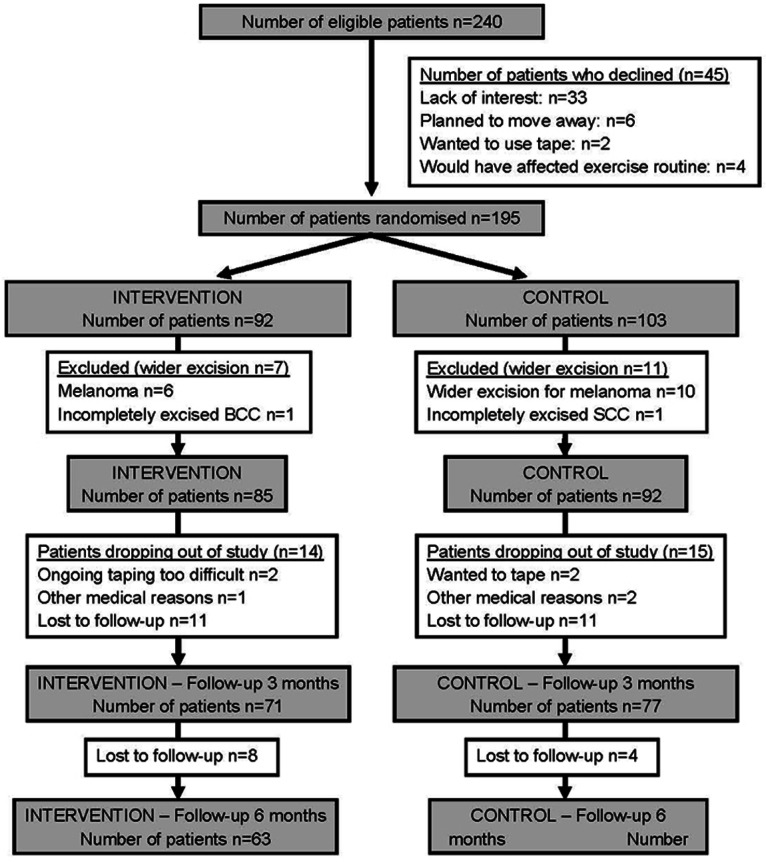

Those with lesions requiring a second wider excision (16 melanoma; two incompletely excised BCCs) were excluded from the study, leaving 177 participants (86 intervention; 91 control). One in-situ melanoma with adequate margins on primary excision remained in the study. Forty-one participants withdrew or were lost to follow-up, leaving 63 (73.3% of 86) in the intervention and 73 (80.2% of 91) in the control group at six months (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Randomization flow chart for participants. [Copyright: ©2013 Rosengren et al.]

At baseline there were no significant differences between study groups (Table 1) with the mean age being 52 years (SD 15.2, range 18 to 80 years) and 53.3% (104) being female. Other than gender there were no differences between the study groups at six months, with 38.4% (28) of controls and 58.7% (37) of intervention participants being female (p=0.013).

Treatment and complications

There was no difference between study groups in the number of deep sutures used (p=0.93; median number three; range from two to ten) or postoperative pain relief requirements (p=0.343). Analgesics used were paracetamol (38), paracetamol with 30 mg codeine phosphate (4) and ibuprofen (2), but 77.4% (151) patients required no pain relief.

One participant developed allergy to the adhesive tapes and subsequently stopped taping. Surgical complications (1 hematoma, 2 infection, 1 dehiscence, 2 stitch abscesses) were as infrequent in both study groups (p=0.804).

Characteristics of non-participants

Forty-five patients declined participation, mainly due to a lack of interest (73.3%). Participants were more likely to be female (p=0.005), less likely to take anticoagulants or inhaled steroids (p=0.049) and reported more exercise in their leisure time (p=0.042) than non-participants. Those who enrolled in but did not complete the study (41) were more likely to be younger (p<0.001), female (p=0.01) and more physically active at work (p=0.036).

Main outcome measures

The overall scar rating given by the blinded assessor at six months was significantly better in the intervention group (p=0.004) (Table 2) both for males (p=0.045) and females (p=0.045). Wounds were rated as good or very good in 64.4% of taped participants and 38.4% controls, whereas they were rated as poor or very poor in 14.6% taped participants and 39.8% controls. Median scar width at six months was 1 mm less in taped participants than controls (p=0.015). When stratified by gender, there was no significant difference in scar width for females (p=0.155), but for men there was a 3.0 mm difference in median width between the control (5.0 mm, IQR = 2.0, 10.0) and intervention groups (2.0 mm, IQR = 1.0, 5.5) (p=0.036) (Table 2). There was no significant difference between study groups in the number of participants with at least some scar depression, elevation or dyschromia.

TABLE 2.

Independent blinded scar assessment at six months

| Control N=73 | Taped N=63 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall rating of scar appearance | 0.004 | ||

| Very good | 11 (15.1%) | 10 (16.1%) | |

| Good | 17 (23.3%) | 29 (46.8%) | |

| Okay | 16 (21.9%) | 13 (21.0%) | |

| Poor | 25 (34.2%) | 10 (16.1%) | |

| Very poor | 4 (5.5%) | 0 | |

| Median width of scar (IQR) [mm] | 4.0 (2.0, 7.5) | 3.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 0.015 |

| Median length of scar (IQR) [mm] | 36.0 (29.0,42.5) | 35.0 (28.0,41.0) | 0.39 |

| Scar elevation | 8 (11.0%) | 4 (6.5%) | 0.55 |

| Scar depression | 26 (35.6%) | 22 (35. 5%) | 0.99 |

| Discolouring | 69 (94.5%) | 57 (91.9%) | 0.73 |

IQR- interquartile range

The intervention was well tolerated with just one of 85 participants initially randomized to the intervention developing an allergy to the tapes. No other problems arose as a result of taping.

Subjective scar assessment at six months was the same in both study groups (p=0.649) even when stratified by gender (Table 3). Only one participant (control) reported the cosmetic outcome to be worse than expected; 98.6% (71) controls and 93.2% (55) of the intervention group would have opted to have the surgery done again (p=0.174) (Table 2). The majority of participants (85.2% intervention group; 71.8% controls; p=0.148) even when stratified by gender (70.4% males; 81.5% females; p=0.221) indicated they would use tapes for a future scar if our results proved favorable (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Participant questionnaire outcome measures at 6 month follow-up

| Control (n=73) | Taped (n=63) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with how your scar looks? | Not answered by 1 | Not answered by 7 | 0.65 |

| Very satisfied | 33 (45.8%) | 25 (43.1%) | |

| Satisfied | 26 (36.1%) | 21 (36.2%) | |

| Neutral | 13 (18.1%) | 11 (19%) | |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Very dissatisfied | 0 | 0 | |

| How does the scar compare with what you expected? | Not answered by 1 | Not answered by 8 | 0.52 |

| My scar is invisible to me | 23 (31.9%) | 18 (31.6%) | |

| My scar is better than I expected | 28 (38.9%) | 16 (28.1%) | |

| My scar is about what I expected | 20 (27.8%) | 23 (40.4%) | |

| My scar is worse than I expected | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | |

| Given the scarring result would you make the same decision to have surgery? | Not answered by 1 | Not answered by 4 | 0.17 |

| Yes | 71 (98.6%) | 55 (93.2%) | |

| If we find that taping does make a difference to the scar would you tape a future torso scar after surgery? | Not answered by 2 | Not answered by 2 | 0.15 |

| Yes | 51 (71.8%) | 52 (85.2%) | |

| No | 4 (5.6%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Don’t know | 16 (22.5%) | 6 (9.8%) |

Though trends suggested that median scar width and overall scar appearance was better in the intervention group three months postoperatively, this did not reach statistical significance. Median scar width was 1 mm less in taped participants (3.0 mm, IQR = 2.0, 5.0) than controls (4.0 mm, IQR = 2.5,6.0) (p=0.064), while overall scar appearance rated good/very good in 53% taped participants compared to 43% controls (p=0.259) at three months following surgery.

Discussion

Twelve weeks of taping torso scars postoperatively significantly improved independent assessment of overall scar appearance at six months. There was no significant difference in the number of participants with at least some scar depression, elevation or dyschromia in the two study groups. Since degree of these three variables was not evaluated, however, these observations may have little clinical relevance.

Taping reduced median scar width by a modest 1 mm, which, though statistically significant, was thought not to be clinically relevant. When stratified by gender, however, the observed 3 mm reduction in scar width in taped males may be of clinical as well as statistical significance. In non-taped controls, scars were significantly wider in males than females, possibly because men subject the torso to more tension and stretch. This could explain why taping, which may help support the healing wound, had a greater impact on scar width in males.

Participant satisfaction was high in our study and not further improved by taping. A major limitation of this study, however, is that we did not have adequate power to show with statistical confidence whether taping affected patient satisfaction levels. Due to time restrictions and a higher than predicted dropout rate, only 136, rather than the required 156 participants, attended for six-month assessment. Furthermore there may have been under-reporting of dissatisfaction, as many participants were well known to their primary health care surgeon and may have wished not to offend. Additionally, almost two-thirds of the excisions were on the upper back, resulting in scars that would have been difficult for some participants to clearly visualize possibly leading to inappropriately high satisfaction scores.

Blinding the doctor to group allocation before wound closure helped ensure a uniform surgical technique for all participants. Fortnightly phone calls may have helped improve compliance in taped participants. Bias in reported satisfaction was prevented by contacting controls with equal regularity. Bias in scar assessment was eliminated by blinding the independent assessor, who used a visual aid to help categorize scars and improve uniformity in scar rating.

Similar to other studies [17,18], we found that the independent assessor was less satisfied with the scar than the participants themselves. Participant satisfaction with torso scars was much higher in our study than in other studies, however [7–9]. Reasons for this may include altered participant expectation and employment of a different suture technique in our study. On recruitment we informed participants that the study was being conducted because torso scars tend to look worse than scars elsewhere. Preoperative expectations are known to be an important determinant of patient satisfaction [8]. Only one participant reported a worse than expected outcome at six months.

Though there has not been sufficient research on the use of absorbable sutures [19], there is evidence that their use in high tension areas results in better scar cosmesis [20]. Furthermore, the use of subcuticular surface sutures avoids additional scars associated with stretched interrupted epithelial suture marks. The two-layered (deep absorbable and subcuticular non-absorbable suture) closure we used may simply have given superior scar aesthetics (increasing participant scar satisfaction) compared to the simple interrupted suture closure used in other studies.

Few studies were found that assessed the cosmetic effect of taping scars. In a randomized prospective study of 39 caesarean section cases, Atkinson et al were able to demonstrate a significant reduction of scar volume where paper tape was applied for 12 weeks along the scar postoperatively [12]. The odds of developing hypertrophic scars were 13.6 times greater in non-taped wounds. In a descriptive paper, Reiffel presented two cases with photographic evidence showing significant improvement in scarring following surgical scar revision and use of paper tapes along the scar for at least two months [13].

It has been postulated that the following three interventions help prevent excessive scar formation: supporting the healing wound to reduce tension (which results in increased collagen synthesis); covering the wound to improve hydration and hasten scar maturity (by down regulating collagen and fibroblast production); and applying pressure to the wound (causing local hypoxia and subsequent fibroblast and collagen degradation) [12,14,19]. In our study long tapes applied close together perpendicular to the wound edges is likely to have reduced wound tension and provided at least intermittent wound pressure (with torso movement). Though the tapes we employed were only partially occlusive, this may also have played a role in improving scar hydration.

Though the trend in our study suggested that taping torso wounds was beneficial at three months, statistical significance was only seen at six months. Any intervention for torso scars might therefore be best followed up for at least six months before discounting its effectiveness. A longer term observational study mapping the natural progress of torso scars is needed to establish just how long they are vulnerable to stretch, as it may well be much longer than six months.

The 12-week period of taping in our study was an arbitrary decision. Perhaps a shorter period of taping is equally effective, or conversely, more prolonged taping gives a superior result. We have outlined several potential reasons for patient satisfaction being high and in particular being equally high in both study groups. Despite this, 82.4% taped participants specified they would tape a future scar if our results proved favorable, indicating that many patients are motivated to improve scar appearance and that 12 weeks of taping is not too onerous.

Conclusion

This study has shown that 12 weeks taping of sutured torso scars is a safe, effective and well-tolerated intervention that may significantly improve scar appearance at six months.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the two recruiting Townsville primary health skin cancer clinics, Skin Alert and Skin Repair, for funding a research nurse and the tapes used in this study. We would like to convey our appreciation to PHCRED for the research grant awarded to Dr. Helena Rosengren. We would also like to thank Sylvia Scully for her invaluable assistance with data entry at Department of General Practice, University of Queensland.

Footnotes

Funding: Helena Rosengren received a research grant through the University of Queensland by an Australian Commonwealth Government initiative, Primary Health Care Research and Evaluation and Development (PHCRED). Funding for the research nurse and assistant and for purchase of skin tapes came from the recruiting skin cancer clinics, Skin Alert and Skin Repair. Otherwise authors had no financial support for the submitted work. The submitted work was not influenced in any way by funding bodies.

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the University of Queensland ethics committee (approval number #2008000535 April 2008). All patients gave written informed consent.

Trial registration: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN126080004963 May 2008)

References

- 1.Brown BC, McKenna SP, Solomon M, Wilburn J, McGrouther DA, Bayat A. The patient-reported impact of scars measure: development and validation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(5):1439–49. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d4fd89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durani P, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. The Patient Scar Assessment Questionnaire: a reliable and valid patient-reported outcomes measure for linear scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(5):1481–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a205de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayat A, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Skin scarring. BMJ. 2003;326(7380):88–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7380.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young V, Hutchison J. Insights into patient and clinician con-cerns about scar appearance: semiquantitative structured surveys. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):256–65. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su CW, Alizadeh K, Boddie A, Lee RC. The problem scar. Clin Plast Surg. 1998;25(3):451–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ladin DA, Garner WL, Smith DJ., Jr Excessive scarring as a consequence of healing. Wound Repair Regen. 1995;3(1):6–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1995.30106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Dixon JB. Prospective study of long-term patient perceptions of their skin cancer surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(3):445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearney CR, Holme SA, Burden AD, McHenry P. Long-term patient satisfaction with cosmetic outcome of minor cutaneous surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42(2):102–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe T, Paoloni R. Sutured wounds: factors associated with patient-rated cosmetic scores. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18(3):259–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staples M, Elwood M, Burton RC, Williams JL, Marks R, Giles GG. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Australia: the 2002 national survey and trends since 1985. Med J Aust. 2006;184(1):6–10. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buettner PG, MacLennan R. Geographical variation of incidence of cutaneous melanoma in Queensland. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16(5):269–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkinson JA, McKenna KT, Barnett AG, McGrath DJ, Rudd M. A randomized, controlled trial to determine the efficacy of paper tape in preventing hypertrophic scar formation in surgical incisions that traverse Langer’s skin tension lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(6):1648–56. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000187147.73963.a5. discussion 1657–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiffel RS. Prevention of hypertrophic scars by long-term paper tape application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(7):1715–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199512000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustoe TA. A randomized, controlled trial to determine the efficacy of paper tape in preventing hypertrophic scar formation in surgical incisions that traverse Langer’s skin tension lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(6) doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000187147.73963.a5. discussion 1657–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz KH, Desciak EB, Maloney ME. The optimal application of surgical adhesive tape strips. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(9):686–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.99084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer AJ, Arora B, Dagum A, Valentine S, Hollander JE. Development and validation of a novel scar evaluation scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(7):1892–7. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287275.15511.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeller U, Kuhimey A, Bajrovic A, et al. Cosmesis from the patient’s and the doctor’s view. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(2):345–54. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rissin Y, Fodor L, Ishach H, Oded R, Ramon Y, Ullmann Y. Patient satisfaction after removal of skin lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(7):951–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tziotzios C, Profyris C, Sterling J. Cutaneous scarring: pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms and scar reduction therapeutics Part II. Strategies to reduce scar formation after dermatologic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durkaya S, Kaptanoglu M, Nadir A, Yilmaz S, Cinar Z, Dogan K. Do absorbable sutures exacerbate presternal scarring? Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32(4):544–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webster DJ, Davis PW. Closure of abdominal wounds by adhesive strips: a clinical trial. Br Med J. 1975;3(5985):696–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5985.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taube M, Porter RJ, Lord PH. A combination of subcuticular suture and sterile Micropore tape compared with conventional interrupted sutures for skin closure. A controlled trial. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1983;65(3):164–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]