Background: The FGF receptors (FGFRs) regulate pleiotropic (diverse) cellular responses.

Results: Serine 779 phosphorylation of FGFR1 and 2 by PKCϵ promotes maximal Ras/MAPK signaling and neuronal differentiation.

Conclusion: The FGFRs quantitatively control signal transduction via receptor serine phosphorylation.

Significance: Receptor tyrosine kinases couple to specific downstream signaling pathways via phosphoserine docking sites to control pleiotropic cellular responses.

Keywords: Differentiation, ERK, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR), Protein Kinase C (PKC), Serine Phosphorylation

Abstract

The FGF receptors (FGFRs) control a multitude of cellular processes both during development and in the adult through the initiation of signaling cascades that regulate proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Although FGFR tyrosine phosphorylation and the recruitment of Src homology 2 domain proteins have been widely described, we have previously shown that FGFR is also phosphorylated on Ser779 in response to ligand and binds the 14-3-3 family of phosphoserine/threonine-binding adaptor/scaffold proteins. However, whether this receptor phosphoserine mode of signaling is able to regulate specific signaling pathways and biological responses is unclear. Using PC12 pheochromocytoma cells and primary mouse bone marrow stromal cells as models for growth factor-regulated neuronal differentiation, we show that Ser779 in the cytoplasmic domains of FGFR1 and FGFR2 is required for the sustained activation of Ras and ERK but not for other FGFR phosphotyrosine pathways. The regulation of Ras and ERK signaling by Ser779 was critical not only for neuronal differentiation but also for cell survival under limiting growth factor concentrations. PKCϵ can phosphorylate Ser779 in vitro, whereas overexpression of PKCϵ results in constitutive Ser779 phosphorylation and enhanced PC12 cell differentiation. Furthermore, siRNA knockdown of PKCϵ reduces both growth factor-induced Ser779 phosphorylation and neuronal differentiation. Our findings show that in addition to FGFR tyrosine phosphorylation, the phosphorylation of a conserved serine residue, Ser779, can quantitatively control Ras/MAPK signaling to promote specific cellular responses.

Introduction

The FGF family of growth factors plays diverse physiological roles during development (e.g., gastrulation, organogenesis, and neurogenesis) and in the adult (e.g., angiogenesis and wound healing) through their ability to regulate pleiotropic cellular responses that include cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation (1, 2). The FGFs exert such pleiotropic activities through the binding and activation of structurally related FGF receptors (FGFR1–4)4 that initiate downstream intracellular signaling cascades (1, 2). FGF binding results in receptor dimerization/oligomerization and the activation of intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, which in turn phosphorylates tyrosine residues in the receptor cytoplasmic tail, as well as associated signaling proteins (1, 2). The binding of Src homology 2 domain proteins to phosphotyrosine docking sites and then serves to physically couple activated FGFRs to downstream signaling pathways including the Ras/MAPK, PI3K, and phospholipase C γ (PLCγ) pathways (1, 2). Additionally, the molecular scaffold protein FRS2α, which is constitutively associated with the juxtamembrane domains of FGFR1 and FGFR2, is tyrosine-phosphorylated following receptor activation and recruits signaling proteins, regulating the PI3K and Ras/MAPK pathways (3).

However, whereas FGFR phosphotyrosine pathways are clearly pivotal for regulating the activities of the FGFs, precisely how they initiate specific intracellular signaling events that lead to distinct biological responses has remained unclear. Of the seven tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic tails of FGFR1 and FGFR2 known to be phosphorylated, two (Tyr653 and Tyr654) act as allosteric regulators of FGFR tyrosine kinase activity and are therefore essential for all biological responses, whereas the remaining 5 (Tyr463, Tyr583, Tyr585, Tyr766, and Tyr730) are thought to provide docking sites for Src homology 2 domain proteins (4, 5). The PC12 pheochromocytoma cell line has provided an important model system for dissecting the molecular mechanisms by which growth factor receptors control intracellular signaling leading to differentiation and neurite outgrowth (6–10). For example, Tyr766 in the C-terminal tail of FGFR1 has been shown to be essential for PLCγ binding and the generation of inositol phosphates. However, blocking these signaling events through mutation of Tyr766 does not impact on the FGF-mediated differentiation and neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells (11, 12). In other studies using chimeric receptors composed of the extracellular domain of the PDGF receptor and the cytoplasmic domain of the FGFR1, Foehr et al. (9) performed tyrosine-scanning mutations to identify specific tyrosines regulating PC12 differentiation and neurite outgrowth. Apart from the known allosteric regulators of FGFR1 tyrosine kinase activity (Tyr653 and Tyr654) and two tyrosines thought to be important for protein folding (Tyr677 and Tyr701), no specific phosphotyrosine docking sites were functionally linked to the ability of growth factor to promote PC12 differentiation (9). Thus, the mechanism by which the FGFRs regulate specific biological responses such as differentiation remains unknown.

In addition to tyrosine phosphorylation, growth factor receptors can also be phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues to provide docking sites for the 14-3-3 family of phosphoserine/threonine-binding proteins. For example, the cytoplasmic tails of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor, EGF receptor, prolactin receptor, and β integrins are known to bind 14-3-3 proteins in a phosphoserine-dependent manner (13–16). Although little is known regarding the roles of 14-3-3 recruitment to activated cell surface receptors, such a mode of signaling would have the potential to trigger biochemically distinct intracellular signals compared with those initiated by receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, providing at least one mechanism by which specificity in signaling and biological outcomes could be achieved. For example, we have shown that the βc subunit of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin 3 receptors is phosphorylated on Ser585 and binds the 14-3-3 proteins to regulate PI3K signaling and hemopoietic cell survival (17). More recently, we have shown that FGFR2 is phosphorylated on Ser779 in response to FGF2 and binds the 14-3-3 proteins (18). However, whether Ser779, which is conserved between FGFR1 and FGFR2, is important for regulating specific intracellular signaling pathways or biological responses such as differentiation has remained unclear.

In these studies, we sought to examine the potential roles of Ser779 signaling in mediating the ability of the FGFs to promote the neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells and primary mouse bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). We show that growth factor stimulation of either PC12 cells or BMSCs triggers the phosphorylation of Ser779 in the cytoplasmic tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2, which is essential for sustained ERK signaling together with neurite outgrowth and differentiation. We further demonstrate that the novel PKC (nPKC) isoform, PKCϵ, is responsible for Ser779 phosphorylation leading to Ras and ERK activation and neuronal differentiation. These findings demonstrate that, in addition to phosphotyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic tails of FGFR1 and FGFR2, the phosphorylation of Ser779 can also initiate intracellular signaling to control specific cellular responses such as neuronal differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

PFR1, which is composed of the hPDGFR-β extracellular domain fused to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of rFGFR1 (kindly provided by Ralph Bradshaw, University of California, San Francisco) (9), was subjected to site-directed mutagenesis as previously described to generate PFR1-S779G, PFR1-Y766F, and PFR1-Y766F/S779G (19). Wild type and mutant hFGFR2 constructs have been described previously (18). PC12 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Hyclone; Invitrogen) and 5% horse serum (HS) (Invitrogen). PC12 cell lines were generated by transfecting with the PFR1, PFR1-Y766F, PFR1-S779G, PFR1-Y766F/S779G, or wt-FGFR2, FGFR2-Y776F, FGFR2-S779G, and FGFR2-Y776F/S779G constructs using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen), and stable pools were isolated by selection in 8 μg/ml blasticidin or 0.5 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). Primary mouse BMSCs were isolated from 6–12-week-old CD1 or C57BL/6 mice and cultured in DMEM with 20% FCS, and adherent cells were passaged when less than 80% confluent, as previously described by Yang et al. (20).

Differentiation Assays

PC12 cells were plated onto collagen-coated (Invitrogen or Sigma) coverslips or 24-well plates at 1.6 × 104 cells/ml in 0.3% HS and stimulated with 8 ng/ml FGF9 (Sigma), 30 ng/ml PDGF-BB (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml FGF2 (R&D Systems), 20 ng/ml EGF (R&D Systems), 50 ng/ml NGF (Alomone Labs), and/or 0.5 ng/ml heparin (R&D Systems) with fresh growth factor addition every 2 days and neurite extension analysis after 3–6 days. Cells demonstrating neurite extensions of at least two cell body lengths were scored by phase contrast microscopy as differentiated. Primary mouse BMSCs were plated at 6 × 105 cells/ml on collagen-coated coverslips and treated with 10 ng/ml FGF2 or 30 ng/ml PDGF-BB for up to 6 days with fresh growth factor addition after 2 days. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, washed, and then permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. The cells were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% normal goat serum (Millipore) for 1 h (h) and then stained with 1:250 of anti-Neurofilament (clone NN18) (Millipore) overnight at 4 °C followed by 1:200 dilution of either a Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 2 h with a Hoechst 33342 counterstain. Differentiation was quantified by fluorescence and phase contrast microscopy with at least 20 fields of view containing >30 cells from duplicate slides. BMSCs that were neurofilament-positive, demonstrating neurite extensions of at least two cell body lengths, were scored as differentiated. For drug treatments, the cells were treated with the SU5402 FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Calbiochem), the PKC inhibitors GF109203X (Tocris Bioscience), Gö6976 (Calbiochem), or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma). PC12 or BMSC transfection of siRNAs (Invitrogen) targeting PKCα (5′-UGAAUUUGUGGUCUUUCACCUCAUG-3′), PKCϵ (5′-UGAAUUUGUGGUCUUUCACCUCAUG-3′), or PKCδ (5′-AAUUGAAGGAGAUGCGAACGA-3′) (100 nm) together with a BLOCK-iT fluorescent tracker oligonucleotide was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) as previously described (21). After 24–48 h, the cells were treated with growth factor, and differentiation was assessed after 2–4 days. Knockdown was confirmed by Western blotting or RT-PCR on purified (TRIzol) total RNA using PKC isoform-specific primers (PKCα, 5′-GTGCAAGGAACACATGATGG-3′ and 5′-CCCACCAGTCCACAGACTTT-3′; PKCϵ 5′-TCGTGAAGCAGATCAACCAG-3′ and 5′-ACCCTCCTTGCAGTGAGCTA-3′; and PKCδ 5′-ATCTGCGGACTGCAGTTTCT-3′ and 5′-CATCCCGAAGTCAGCAATCT-3′).

Modeling of a Complex between FGFR1 and 14-3-3ζ

The crystal structure of c-RAF peptide complexed to human 14-3-3ζ (Protein Data Bank code 4FJ3) together with the crystal structure of human FGFR1 in complex with rat PLCγ (Protein Data Bank code 3GQI) were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (22, 23). The c-RAF phosphopeptide was changed to the FGFR1 sequence, 776YSPpSFPDT783, in PyMOL. The crystal structure of FGFR1 was manually positioned adjacent to the “mutated” c-RAF structure and the missing amino acids, 771MPLDQ775, were constructed in Sybylx2.0 and attached to the FGFR tail. The whole complex was then minimized sequentially (first hydrogens, then side chains, and finally all atoms) in Sybylx2.0 under the Tripos force field for 10,000 iterations.

Cell Viability Assays

The cells were stained with 200 nm tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (Invitrogen) for 30 min as previously described (18). Cells with intact mitochondria retain the tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester stain and were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Morphogen Assay

PC12 cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/ml in DMEM with 10% FCS. After 24 h, the medium was removed, and cells were overlaid with 0.375% agar containing DMEM with 0.15% HS and 500 ng/ml heparan sulfate. A growth factor gradient was then established by placing a PDGF-agarose “plug” (consisting of 400 ng/ml PDGF made up in 1% agarose/DMEM that was allowed to set as a 40-μl plug) on the agar. After 48 h, the cells were fixed in situ using 8% paraformaldehyde/PBS containing Hoescht 33342. Differential counts were determined for (i) condensed or blebbing of nuclei (dead cells with hallmarks of apoptosis), (ii) intact nuclei in PC12 cells not bearing neurites (cell survival alone), and (iii) intact nuclei associated with PC12 cells bearing neurite extensions (cell survival together with differentiation). The cells were counted in >10 fields of view at increasing distances (mm) from the PDGF plug. The “survival zone” is defined as a spatially distinct region within the PDGF gradient where PC12 cells survive but do not differentiate. This region is arbitrarily defined as the region in which differentiation was observed in <10% of PC12 cells and survival was >50% of the maximum.

Immunoprecipitation/Pulldowns/Western Blots

PC12 cells or BMSCs were plated in DMEM with 0.3% HS overnight, following which they were stimulated with 8 ng/ml FGF9, 30 ng/ml PDGF-BB, 10 ng/ml FGF2, 20 ng/ml EGF, 50 ng/ml NGF, and/or 0.5 ng/ml heparin. Following stimulation, the cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer, and specific proteins were immunoprecipitated and subjected to Western blot analysis essentially as previously described (18, 19). Immunoprecipitations (2 × 107 cells) were performed for 2 h at 4 °C using 1 μg of either the anti-FGFR2 C17 pAb (Santa Cruz), the anti-9E10 mAb, or the anti-FRS2 pAb (Cell Signaling) adsorbed to protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). Immunoblots were then performed using 1 μg/ml 4G10 anti-phosphotyrosine mAb (Cell Signaling), 1:200 anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR phospho-specific pAb (18), 1:200 anti-FGFR2 C17 pAb (Santa Cruz), or 1:200 anti-FRS2 pAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). In addition, the activation of Ras was assessed by performing pulldowns from cell lysates using either GST or GST Ras-binding domain (RBD) of c-Raf (GST-RBD) bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin (Millipore) as previously described (19). Active GTP-loaded Ras was precipitated using GST-RBD and detected using 1:500 anti-Ras pAb (BD Transduction Laboratories). Immunoblots were also performed using anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Thr204), anti-phospho-JNK (Thr183/Thr185), anti-phospho-MSK1 (Thr581), anti-phospho-ATF2 (Thr71) (Cell Signaling), anti-ERK, anti-actin (Chemicon), anti-PKCϵ, and PKCδ pAbs (Santa Cruz).

In Vitro Kinase Assays

A peptide encompassing Ser779 of FGFR2 (KEQYSPSYPDTRC) (Chemicon) was incubated with 100 ng of PKCϵ (Millipore) in kinase buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 3 mm MgCl2, 3 mm MnCl2, 3 μm NaVO4, 1 mm DTT, 165 mm CaCl2) with 3 μl of phosphatidyl serine lipid activator (Millipore) and 100 mm ATP in the presence or absence of GF109203X. For inhibitor-treated samples, the peptides were preincubated with inhibitor for 20 min at 4 °C prior to addition of ATP and incubation for 40 min at 30 °C. Kinase reactions were then spotted onto nitrocellulose and immunoblotted with phospho-specific anti-Ser(P)779 pAb. In vitro PI3K assays were performed on anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10) immunoprecipitations using [γ-32P]ATP and phosphatidyl inositol phosphates as previously described (17).

ERK Immunofluorescence

PC12 cells were plated onto collagen-coated coverslips and cultured overnight in DMEM with 0.3% HS. The cells were then stimulated with 8 ng/ml FGF9 for 30 min and then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS, washed, and permeabilized 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS followed by blocking in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were probed with 1/500 anti-ERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C, washed, and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). The slides were analyzed by confocal microscopy (Nikon C1) using EZ-C1 software (Nikon).

RESULTS

Ser779 in the Cytoplasmic Tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2 Is Required for Growth Factor-regulated PC12 Survival and Differentiation

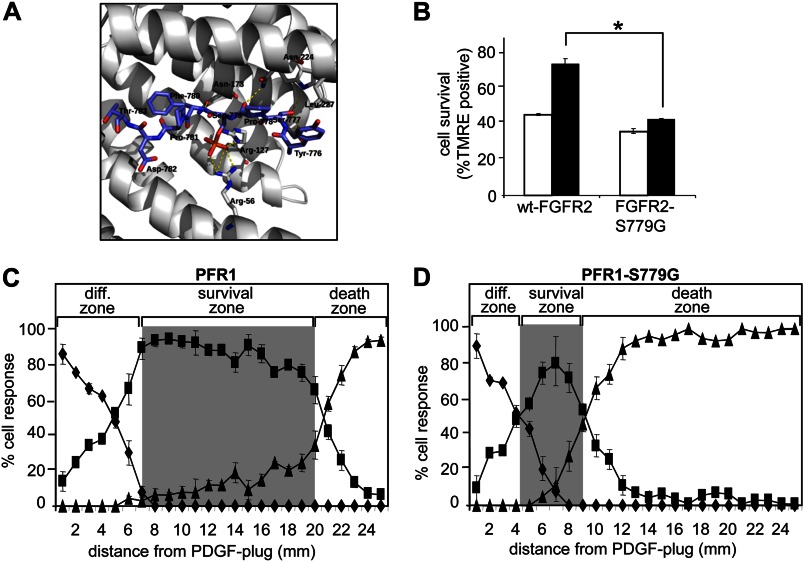

We have previously identified a conserved motif, 775QYSPSYP781, in the C-terminal tail of FGFR2 in which Ser779 (underlined) is phosphorylated following FGF2 stimulation and initiates intracellular signaling via the binding of the 14-3-3 family of adaptor or scaffold proteins (18). This is supported by computational modeling of a FGFR1 peptide containing Ser(P)779 into the crystal structure of 14-3-3ζ and showed that the peptide exhibited numerous interactions within the 14-3-3 binding cleft (Fig. 1A). Namely, Ser777 of FGFR1 displays hydrogen bonds between its side chain and the side chains of Trp228 and Glu180 of 14-3-3. There were also polar interactions seen between the side chain of the phosphorylated Ser779 and the side chains of Arg56 and Arg127 from 14-3-3. There were also polar interactions between the backbone of FGFR1 and Asn173 and Asn224. Additionally, there were numerous van der Waals interactions, including between Tyr776 of FGFR1 and Leu227 of 14-3-3. These interactions fit with the known critical binding motif for phosphoserine-containing peptides, including the binding of c-Raf to 14-3-3 (24). However, the precise role of Ser779 phosphorylation and its interaction with 14-3-3 in regulating downstream signaling pathways and specific cellular responses remains unclear.

FIGURE 1.

Ser779 in the cytoplasmic tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2 is required for growth factor-regulated PC12 cell survival. A, model constructed for the binding of 14-3-3ζ to Ser(P)779 of FGFR1 based on 14-3-3ζ and FGFR1 crystal structures. Multiple interactions are depicted including potential hydrogen bonds (yellow dashed lines) between the FGFR1 peptide (sticks with purple carbons) and 14-3-3 (shown in ribbon style with gray carbons and key interacting residues as sticks). B, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G were plated in the absence (open bars) or presence (black bars) of 8 ng/ml FGF9. Cell viability was determined by tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) staining and flow cytometry after 96 h. *, p < 0.05. C and D, PC12 cells expressing PFR1 (C) or PFR1-S779G (D) were plated and allowed to adhere for 24 h. The cells were then overlaid with agar/medium, and a PDGF-agarose plug was placed on the agar at one end of the dish. After 48 h, the cells were stained in situ with Hoechst 33342, and fluorescent/light microscopy was used to determine (i) cell differentiation and survival (diamonds), (ii) cell survival but no differentiation (squares), or (iii) cell death (triangles) at the indicated distances from the plug. The differentiation zone (diff. zone), survival zone (gray shading), and death zone are indicated. The error bars represent standard deviations, and the results are typical of at least two independent experiments.

The PC12 pheochromocytoma cell line has been widely used as a model system for examining the mechanisms by which growth factors such as the FGFs are able to independently regulate cellular responses such as survival and neuronal differentiation (6–10). PC12 cells express FGFR1, FGFR3, and FGFR4, whereas FGFR2 expression is undetectable (8). Thus, because FGF9 preferentially activates the IIIc isoform of FGFR2, the roles of specific FGFR2 residues in regulating PC12 cellular responses can be examined following expression of FGFR2 mutants and stimulation with FGF9 (25, 26). To determine whether Ser779 signaling was functionally linked to specific cellular responses, we first compared the ability of FGF9 to promote cell viability in PC12 cells expressing either wt-FGFR2 or the FGFR2-S779G mutant that fails to bind 14-3-3 using low serum conditions where growth factor stimulation promotes cell survival in the absence of differentiation. Although FGF9 was able to promote the survival of PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2, this response was significantly reduced in cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant (Fig. 1B).

To further investigate the role of Ser779 in FGFR-mediated responses, we also employed a chimeric receptor system composed of the extracellular domain of the PDGFRβ fused to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of FGFR1 (PFR1). Stimulation of cells expressing the PFR1 with PDGF allows the analysis of FGFR1 signaling and biological functions in the absence of activated endogenous FGFRs (8, 9, 27, 28). Using this system, we assessed the role of Ser779 in an in vitro morphogen assay in which PC12 cell survival and differentiation were quantitated across a transient gradient of growth factor established in semisolid agar medium. PC12 cells expressing either PFR1 or the PFR1-S779G mutant chimeric receptor were overlaid with agar, following which a PDGF plug was placed on the agar. As shown in Fig. 1C, diffusion of PDGF from the plug established a growth factor gradient whereby PC12 cells expressing PFR1 in close proximity to the plug underwent differentiation (diamonds; labeled diff. zone), cells further from the plug were able to survive in response to growth factor but did not differentiate (squares; survival zone, gray), and cells more distant from the plug neither differentiated nor survived and underwent cell death (triangles; death zone) (Fig. 1C). Although the differentiation zones extended to similar distances in cells expressing PFR1 and the PFR1-S779G mutant, the survival zone was clearly contracted (Fig. 1, C and D, compare gray zones), indicating that Ser779 can regulate the survival of PC12 cells.

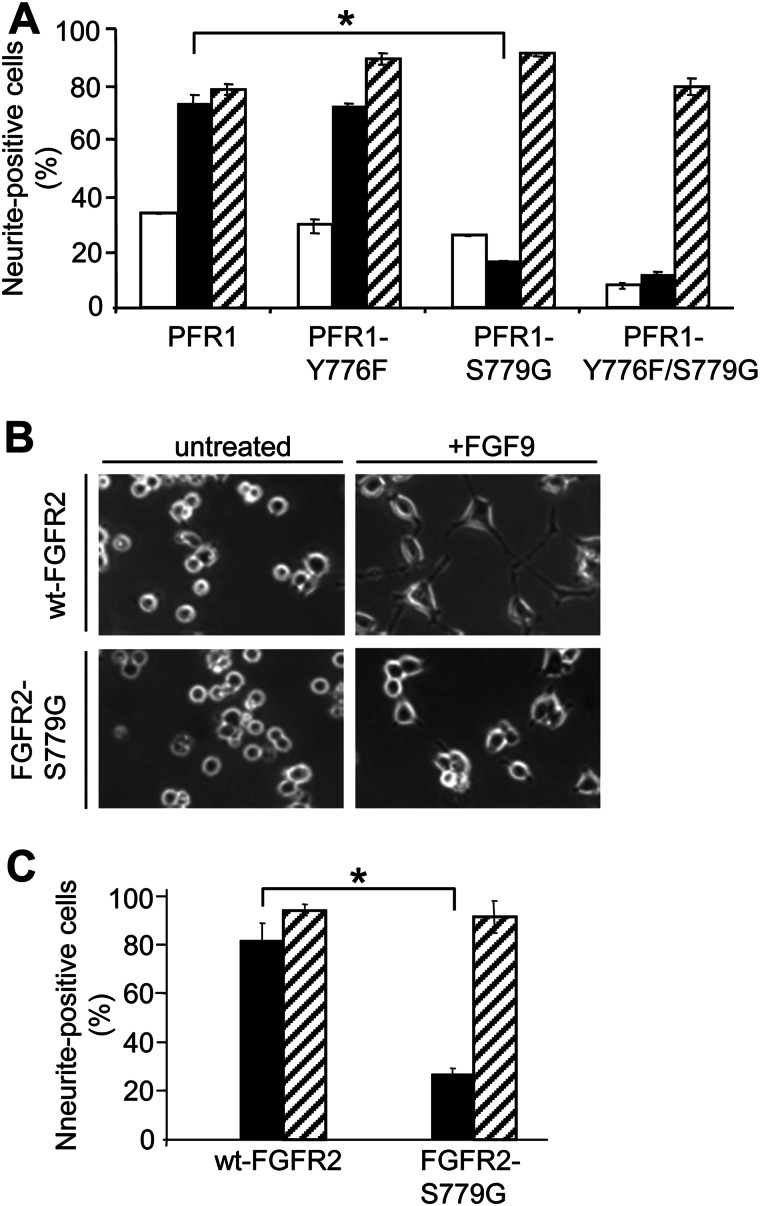

The differentiation observed in the in vitro morphogen assay was transient and reversible and most likely reflects the transient nature of the growth factor gradient established in semisolid agar. We therefore further examined the potential role of Ser779 in a conventional PC12 differentiation assay. For these assays, we also included a Y766F mutant (PFR1-Y766F), which has previously been shown to be defective in the recruitment and activation of PLCγ (11), as well as a PFR1-Y766F/S779G double mutant. Consistent with previous reports, cells expressing the PFR1-Y766F chimeric mutant demonstrated no defect in their ability to differentiate in response to PDGF (Fig. 2A) (11). However, a significant reduction in PDGF-mediated differentiation was observed for cells expressing the PFR1-S779G mutant when compared with cells expressing PFR1 (Fig. 2A, bracketed black bars). The inability of the PFR1-S779G mutant to promote differentiation was not due to a cell intrinsic defect because NGF (positive control) was able to promote differentiation to levels similar to that observed in cells expressing PFR1 (Fig. 2A, hatched bars). Cells expressing the PFR1-Y766F/S779G double mutant were defective in their response to PDGF to a similar extent as cells expressing PFR1-S779G, indicating that Ser779 is primarily responsible for transducing signals necessary for PC12 differentiation. In line with the results obtained with the PFR1-S779G chimeric receptor, PC12 cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant were also defective in their ability to differentiate in response to FGF9, confirming that Ser779 is critical for initiating signals that promote the differentiation of PC12 cells (Fig. 2, B and C).

FIGURE 2.

Ser779 in the cytoplasmic tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2 is required for growth factor-regulated PC12 cell differentiation. A, PC12 cells expressing PFR1, PFR1-Y766F, PFR1-S779G, and PFR1-Y766F/S779G were either not stimulated (open bars) or stimulated with 30 ng/ml PDGF-BB (black bars) or 50 ng/ml NGF (positive control, hatched bars) for 6 days with growth factor addition on days 0, 2, and 4. Cell differentiation, as determined by neurite extension, was quantified on day 6. B, phase microscopy of PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G following no stimulation (untreated) or FGF9 stimulation (8 ng/ml) for 4 days. C, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G were either not stimulated (open bars not visible as there was 0% differentiation) or stimulated with 8 ng/ml FGF9 (black bars) or 50 ng/ml NGF (hatched bars) for 4 days. Quantification of cell differentiation was determined by neurite extension. The error bars represent standard deviations, and the results are typical of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

Ser779 in the Cytoplasmic Tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2 Is Required for Maximal ERK Activation

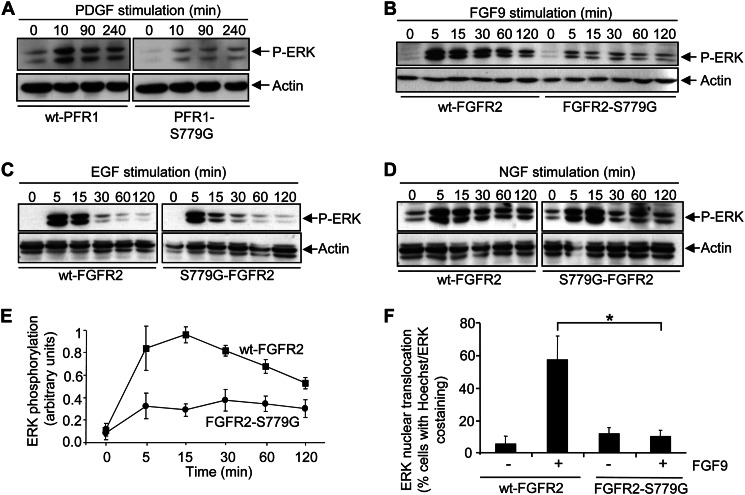

Previous studies have proposed that differences in the strength or duration of signaling in PC12 cells may account for the ability of pleiotropic growth factors to promote different cellular outcomes (6). For example, growth factors that promote PC12 differentiation such as FGF and NGF induce sustained activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway, whereas growth factors that promote PC12 proliferation such as EGF induce transient Ras/MAPK activation (6). We therefore examined the role of Ser779 in the activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway. As shown in Fig. 3A, growth factor stimulation of PC12 cells expressing PFR1 resulted in sustained ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas in cells expressing the PFR1-S779G mutant, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was reduced. Similarly, stimulation of cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant with FGF9 resulted in decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation compared with cells expressing the wt-FGFR2 (Fig. 3B). As has been reported by others, we observed the expected transient kinetics of ERK1/2 phosphorylation following EGF stimulation and sustained kinetics following NGF stimulation, which indicated that there was no cell intrinsic defect in Ras/MAPK signaling (Fig. 3, C and D). Importantly, although the amplitude of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant, the signaling kinetics did not appear to be affected with elevated ERK1/2 phosphorylation clearly detectable up to 2 h following FGF9 stimulation (Fig. 3, B and E).

FIGURE 3.

Ser779 in the cytoplasmic tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2 is required for maximal ERK activation. A–D, PC12 cells expressing PFR1 or PFR1-S779G (A) or wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G (B–D) were stimulated with PDGF-BB (A), FGF9 (B), EGF (C), or NGF (D) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-ERK and anti-actin pAb. E, quantitation of the phospho-ERK signals following FGF9 stimulation of PC12 cells expressing either wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G from three independent experiments. F, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G were either not stimulated (−) or stimulated (+) with FGF9 for 2 h, following which the cells were fixed and stained with anti-ERK pAb, Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit secondary antibody, and Hoechst 33342. ERK nuclear translocation, as determined by the co-localization of ERK (Alexa Fluor 488) and nuclei (Hoechst 33342), was quantified by fluorescence microscopy. The error bars represent standard deviations, and the results are typical of at least two independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

ERK activation is accompanied by its translocation to the nucleus where it is important for the regulation of gene expression programs necessary for mediating cellular responses. We therefore also assessed the nuclear translocation of ERK following FGF9 simulation of PC12 cells. ERK co-localized with Hoechst nuclear staining following FGF9 stimulation of cells expressing wt-FGFR2 but remained in the cytoplasm of cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant (data not shown). Quantification of these results demonstrated that ERK translocation to the nucleus was significantly reduced in cells expressing FGFR2-S779G when compared with cells expressing FGFR2 (Fig. 3F).

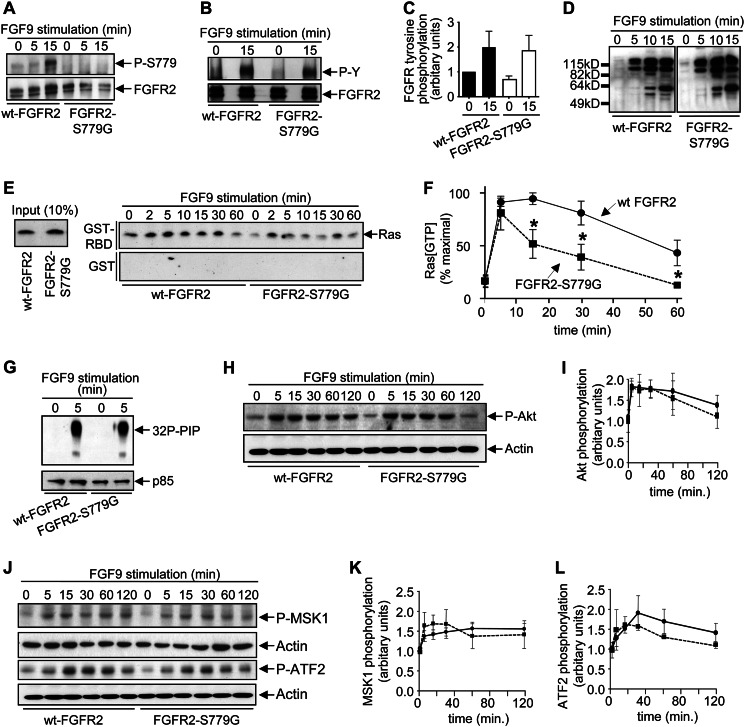

To further understand the molecular mechanisms by which Ser779 might promote ERK signaling, we first examined the receptor-proximal signaling events regulated by FGFR2. FGF9 stimulation clearly induced Ser779 phosphorylation of wt-FGFR2, whereas no such phosphorylation was detected in the FGFR2-S779G mutant (Fig. 4A). Tyrosine phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tail of FGFR2 as well as the associated scaffold protein, FRS2α, has been shown to be important for initiating intracellular signaling including the activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway (1–3). Compared with cells expressing wt-FGFR2, there was no detectable defect in the tyrosine phosphorylation of either the mutant FGFR2-S779G receptor (Fig. 4, B and C) or FRS2α (data not shown) following FGF9 stimulation. Furthermore, FGF9 stimulation induced a similar panel of phosphotyrosine proteins in cells expressing wt-FGFR2 and FGFR2-S779G (Fig. 4D). Ras, MEK, and ERK constitute a signaling cassette in which Ras has been widely shown to be an upstream regulator of ERK. FGF9 stimulation resulted in the induction of Ras activity in both wt-FGFR2 and FGFR2-S779G PC12 cells. However, the kinetics were significantly more transient in FGFR2-S779G cells compared with wt-FGFR2 cells (Fig. 4, E and F). On the other hand, no defect was observed in the ability of the FGFR2-S779G mutant to induce the lipid kinase activity of PI3K (Fig. 4G) or phosphorylation of the downstream PI3K target, Akt (Fig. 4, H and I). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the phosphorylation of other FGFR downstream targets, MSK1 and ATF2 (Fig. 4, J–L). Collectively, these results indicate that the phosphorylation of Ser779 is selectively required for the full activation of Ras/MAPK signaling but is not required for the regulation of other pathways downstream of FGFRs.

FIGURE 4.

Ser779 of FGFR2 is required for sustained Ras activation but not for the regulation of FGFR2 tyrosine phosphorylation pathways or PI3K signaling. A and B, PC12 cells expressing either wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G were stimulated with 8 ng/ml FGF9 and lysed, and FGFR2 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with the anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR phosphospecific antibodies (A) or 4G10 anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (B). C, FGFR2 tyrosine phosphorylation from two independent experiments were quantified by laser densitometry. D, PC12 cells were stimulated as in A, and whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with 4G10 anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. E, PC12 cells were stimulated as in A, following which lysates were subjected to pulldowns using either GST-Sepharose (control) or GST-RBD-Sepharose (which binds GTP-bound active Ras but not GDP-bound inactive Ras). Pulldowns were then immunoblotted with anti-Ras antibodies. Increased Ras precipitation by GST-RBD following FGF9 stimulation indicates the presence of increased levels of GTP-loaded active Ras within cells. Input lysates (10% of that used for the pulldowns) are indicated on the left. F, quantitation of four independent Ras pulldown experiments by laser densitometry. *, p < 0.05. G, PC12 cells were stimulated as in A, following which cells were lysed, and 4G10 immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro lipid kinase assays using [γ-32P]ATP and phosphatidylinositol phosphates as substrates. Phosphorylated lipids (32P-PIP) were then extracted and subjected to thin layer chromatography with the signals being detected by autoradiography (upper panel). The p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K was detected by immunoblot analysis (lower panel). H, PC12 cells were stimulated as in A and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-Akt antibodies. I, phospho-Akt signals from three independent experiments were quantified by laser densitometry. J, PC12 cells were stimulated as in A, following which cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. K and L, phospho-MSK1 signals (K) and phospho-ATF2 signals (L) from two independent experiments were quantified by laser densitometry.

FGFR2-regulated PC12 Neuronal Differentiation Occurs via PKCϵ

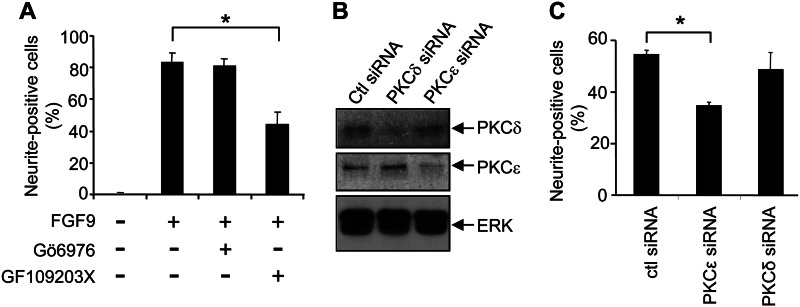

Although tyrosine phosphorylation of growth factor receptors is critical for initiating signaling via the Ras/MAPK pathway in diverse cellular settings, our findings indicated that FGFR serine phosphorylation could also regulate Ras/MAPK signaling. The PKC family of serine/threonine kinases has been shown to be an important regulator of Ras/MAPK signaling initiated by growth factor receptors (29, 30). We therefore considered the possibility that Ser779 of FGFR may signal via PKC to promote the sustained and full activation of Ras and ERK necessary for PC12 differentiation. Previous studies have shown that growth factor stimulation of PC12 cells results in the activation of the conventional PKC (cPKC) isoforms, PKCα and PKCβ, as well as nPKC isoforms, PKCδ and PKCϵ (31). Inhibition of both cPKC and nPKC with the pan-PKC inhibitor GF109203X significantly reduced PC12 differentiation in response to FGF9, whereas the cPKC-selective inhibitor, Gö6976 (32), failed to reduce PC12 differentiation, suggesting a role for nPKC isoenzymes in these responses (Fig. 5A). We therefore examined the ability of FGF9 to promote PC12 differentiation following the siRNA-mediated knockdown of the nPKCs, PKCϵ and PKCδ (Fig. 5B). Although knockdown of PKCδ had no effect on FGF9-mediated differentiation of PC12 cells, there was a significant reduction following PKCϵ knockdown (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the role of PKCϵ in transducing FGFR2 signals was specifically required for PC12 differentiation because cell survival in response to FGF9 following PKCϵ knockdown was unaffected (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of the nPKC isoform, PKCϵ, impairs FGF9-induced differentiation of PC12 cells. A, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 were stimulated with 8 ng/ml FGF9 either in the presence (+) or absence (−) of the PKC inhibitors 5 μm Gö6976 and/or 5 μm GF109203X, and differentiation was quantified after 4 days. B, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 were transfected with either 100 nm control siRNA or siRNA targeting PKCϵ or PKCδ, and protein expression was determined by Western blot after 48 h. C, PC12 cells were transfected with 100 nm of the indicated siRNAs and after 24 h were stimulated with FGF9, and differentiation was quantified after 48 h. The error bars represent standard deviations, and the results are typical of at least two independent experiments. *, p < 0.05. Ctl, control.

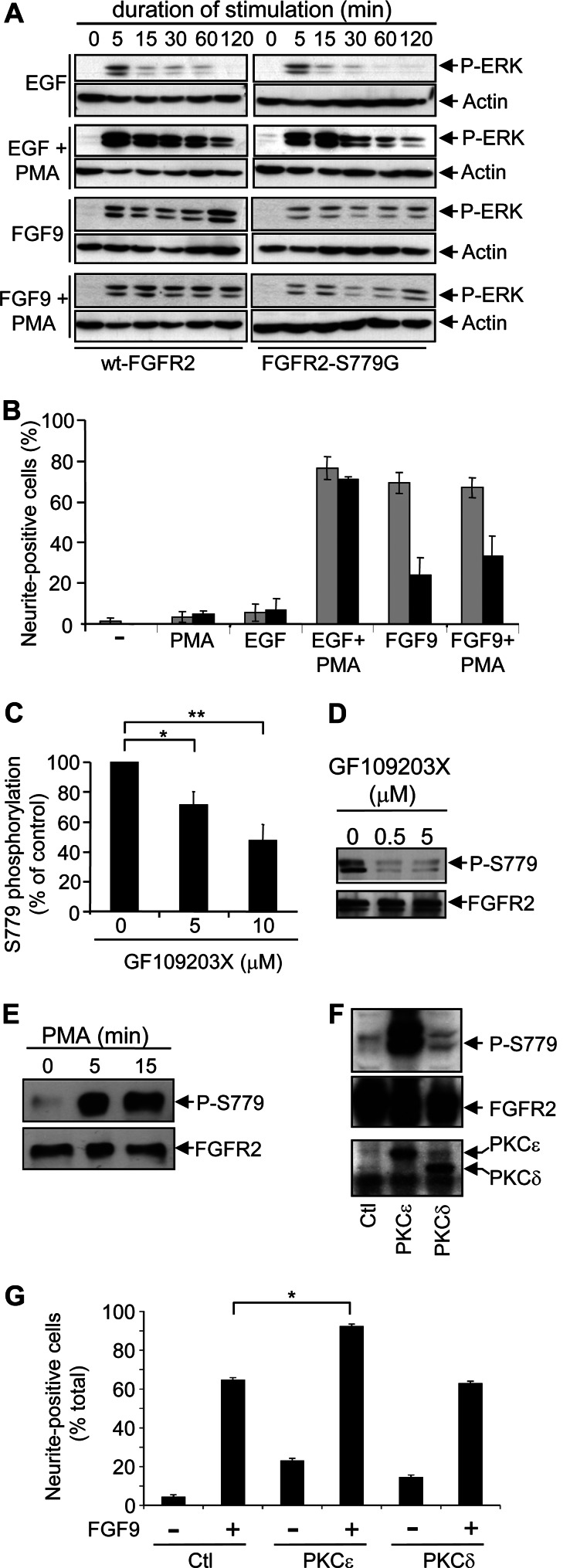

If Ser779 signaling is responsible for the downstream activation of PKC leading to sustained ERK activation, enforced PKC activation in FGFR2-S779G cells may complement the defect in ERK signaling and rescue the differentiation response. For example, it is known that although EGF stimulation of PC12 cells results in transient ERK phosphorylation and proliferation, co-stimulation with EGF and the PKC activator, PMA, results in sustained ERK phosphorylation and PC12 differentiation (33). However, in contrast to the ability of EGF/PMA co-stimulation to augment ERK signaling and promote PC12 differentiation (Fig. 6, A and B), FGF9/PMA co-stimulation of FGFR2-S779G cells failed to restore ERK signaling or differentiation to levels observed in wt-FGFR2 cells (Fig. 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

PKCϵ phosphorylates Ser779 of FGFR2. A, PC12 cells expressing either wt-FGFR2 or FGFR2-S779G were stimulated with 20 ng/ml EGF, 8 ng/ml FGF9, and/or 100 nm PMA for up to 2 h, following which cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. B, PC12 cells expressing either wt-FGFR2 (gray bars) or FGFR2-S779G (black bars) were stimulated as in A with EGF, FGF9, and/or PMA, and differentiation, as determined by neurite extension, was quantified after 48 h. C, in vitro kinase assays were performed using a peptide encompassing Ser779 of FGFR2 and purified recombinant PKCϵ either in the presence or absence of GF109203X. The reactions were spotted onto nitrocellulose filters, and the phosphorylation of the Ser779 peptide was determined by immunoblot analysis using the anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR2 phospho-specific antibodies. *, p = 0.04; **, p = 0.01. D, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 were pretreated with GF109203X for 30 min followed by stimulation with 8 ng/ml FGF9 for 10 min. FGFR2 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with the anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR2 phospho-specific antibodies. E, PC12 cells expressing wt-FGFR2 were stimulated with PMA, following which FGFR2 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoblotted with the anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR2 phospho-specific antibodies. F, PC12 cells were transfected with constructs for the expression of PKCϵ, PKCδ, or an empty vector (Ctl). After 48 h, cells were lysed, and FGFR2 immunoprecipitates were blotted with anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR2 phospho-specific antibodies or anti-FGFR2 antibodies. Cell lysates were also sequentially immunoblotted with anti-PKCϵ and anti-PKCδ antibodies. G, PC12 cells transfected with the indicated expression constructs were subjected to a differentiation assay in the presence (+) or absence (−) of FGF9, and neurite-positive cells were counted after 48 h. The error bars represent standard errors, and the results are typical of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

One possible explanation for these results is that PKC lies upstream of Ser779. Our previous studies using the Predikin structure-based modeling algorithm for identifying substrate-kinase interactions identified PKC as a potential kinase phosphorylating Ser779 of FGFR2 (18). As shown in Fig. 6C, purified recombinant PKCϵ was able to phosphorylate a peptide encompassing Ser779 of FGFR2 in vitro, and this activity was significantly reduced by the PKC inhibitor, GF109203X. Consistent with the ability of PKC to phosphorylate Ser779 in vitro, treatment of PC12 cells with GF109203X resulted in a decrease in Ser779 phosphorylation following FGF9 stimulation, whereas PMA stimulation resulted in increased in Ser779 phosphorylation in the absence of growth factor (Fig. 6, D and E). Furthermore, overexpression of PKCϵ but not PKCδ increased Ser779 phosphorylation in PC12 cells in the absence of FGF9 and enhanced FGF9-mediated differentiation (Fig. 6, F and G). Thus, our results show that at least one role for PKCϵ in promoting PC12 differentiation is via its ability to phosphorylate Ser779 of FGFR2 and initiate downstream signaling.

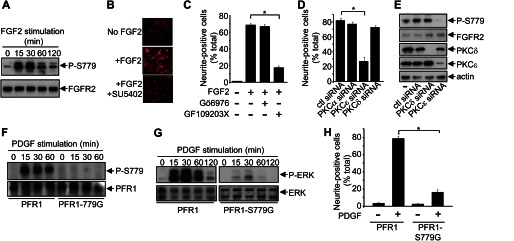

PKCϵ-mediated Phosphorylation of Ser779 in FGFR2 Regulates Sustained ERK Phosphorylation and Neuronal Differentiation of BMSCs

In addition to the ability of the FGFs to promote neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells, stimulation of primary mouse BMSCs with FGF2 is also able to promote neuronal differentiation characterized by the appearance of neurite extensions and the expression of the neuronal marker, neurofilament (20). Using this model system, we show that FGF2 stimulation results in increased Ser779 phosphorylation of endogenous FGFR2, the projection of neurite extensions, and the up-regulation of neurofilament (Fig. 7, A and B). Consistent with the findings in PC12 cells, GF109203X significantly inhibited BMSC neuronal differentiation in response to FGF2, whereas Gö6976 had no effect, suggesting a role for nPKC isoforms (Fig. 7C). In line with such a proposal, siRNA knockdown of the nPKC PKCϵ, but not the related nPKC member PKCδ or the cPKC isoform PKCα, significantly reduced BMSC differentiation following FGF2 stimulation (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, siRNA-mediated knockdown of PKCϵ, but not PKCδ, resulted in a decrease of growth factor-induced Ser779 phosphorylation of the endogenous FGFR2 (Fig. 7E). These results indicate that PKCϵ is required for Ser779 phosphorylation of FGFR2.

FIGURE 7.

PKCϵ-mediated phosphorylation of Ser779 in FGFR2 regulates sustained ERK phosphorylation and neuronal differentiation of BMSCs. A, primary mouse BMSCs were stimulated with FGF2 for the indicated times, following which cells were lysed, and FGFR2 immunoprecipitates were blotted with the anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR phospho-specific antibodies or FGFR2 antibodies. B, primary mouse BMSCs were plated onto collagen-coated coverslips and either not stimulated (No FGF2), stimulated with FGF2 (+FGF2), or stimulated with FGF2 in the presence of the FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU5402 (+FGF2 +SU5402) for 4 days with fresh growth factor and drug added after 2 days. The cells were then fixed and stained with 1:250 of anti-Neurofilament (clone NN18) overnight at 4 °C and then counterstained with Hoechst 33342. C, primary mouse BMSCs were stimulated with FGF2 either in the presence (+) or absence (−) of the PKC inhibitors 5 μm Gö6976 and/or 5 μm GF109203X, and differentiation was quantified after 4 days. D and E, primary mouse BMSCs were either nontransfected (−) or transfected with 100 nm control siRNA (ctl) or siRNA targeting specific PKC isoforms. After 24 h, either the cells were stimulated with FGF2, and differentiation was quantified after 48 h (D), or the cells were lysed and the indicated immunoblots were performed (E). F, primary BMSCs expressing either PFR1 or PFR1-S779G were stimulated with PDGF-BB for the indicated times, following which PFR1 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Ser(P)779-FGFR phospho-specific antibodies or 9E10 mAbs. G, primary BMSCs expressing either PFR1 or PFR1-S779G were stimulated with PDGF-BB for the indicated times, following which cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-ERK antibodies or anti-ERK antibodies. H, primary BMSCs expressing PFR1 or PFR1-S779G were stimulated (+) with PDGF-BB for 6 days with growth factor addition every 2 days. Cell differentiation was quantified on day 6. The error bars represent standard errors, and the results are typical of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

We then further examined the role of Ser779 in regulating ERK signaling and BMSC neuronal differentiation using the PFR1 chimeric receptors. Growth factor stimulation of BMSCs expressing PFR1 resulted in increased Ser779 phosphorylation, which was not detected in cells expressing the PFR1-S779G mutant (Fig. 7F). Importantly, whereas BMSCs expressing the PFR1 demonstrated sustained ERK phosphorylation and differentiation following growth factor stimulation, both of these responses were reduced in cells expressing the PFR1-S779G mutant (Fig. 6, G and H). Thus, our results show that PKCϵ-mediated phosphorylation of Ser779 in FGFR2 is critical for regulating the intracellular signaling events necessary for maximal Ras/MAPK signaling and neuronal differentiation.

DISCUSSION

Although the ability of growth factor receptor tyrosine phosphorylation to control diverse cellular responses represents a central paradigm in cell biology, the functional roles of receptor serine phosphorylation are less well understood. We now show that Ser779 in the cytoplasmic tail of FGFR1 and FGFR2 is essential for transducing specific intracellular signals and biological responses in both PC12 cells and primary BMSCs. Using an FGFR2-S779G mutant as well as a PFR1-S779G chimeric mutant, we have shown that Ser779 signaling is required for the survival of PC12 cells under conditions where growth factor concentrations are limiting (Fig. 1). In addition, Ser779 signaling is required for the neuronal differentiation of both PC12 cells and primary mouse BMSCs (Figs. 2 and 7). Sustained activation of ERK is known to be an important requirement for the ability of growth factors such as the FGFs to promote PC12 differentiation, whereas transient activation of ERK by factors such as EGF promote PC12 proliferation (6). We show that although both the FGFR2-S779G and PFR1-S779G mutants were able to induce Ras activation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, the kinetics of Ras activation was shorter, and the magnitude of ERK phosphorylation was reduced (Figs. 3, 4, and 7).

Importantly, no detectable defect in FGFR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation pathways were observed in cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant, suggesting that the reduction in Ras and ERK signaling was not due to an overall defect in receptor signaling (Fig. 4). Similarly, no defect in PI3K activation or Akt phosphorylation was observed in cells expressing the FGFR2-S779G mutant (Fig. 4). Furthermore, there was no significant defect in the phosphorylation of two known nuclear targets of FGFR signaling, MSK1 and ATF2 (Fig. 4). Thus, our findings demonstrate that Ser779 in the cytoplasmic tails of FGFR1 and FGFR2 selectively couples the activated receptor to the Ras/MAPK pathway to promote differentiation.

Multiple PKC isoforms have been identified as downstream targets of growth factor receptors where they play important roles in regulating the Ras/MAPK pathway. For example, PKC has been shown to increase Ras activity in B cells via its ability to phosphorylate the guanine nucleotide exchange factor RASGRP3 and promote Ras GTP loading (34). In addition, PKCϵ has been identified together with B-Raf and S6K2 in multimeric complexes where it can potentially phosphorylate Raf and promote FGF2-mediated survival (35, 36). However, although these and other studies clearly show that PKC provides signaling inputs to multiple downstream targets within the Ras/MAPK cassette, our current findings identify an additional upstream receptor-proximal role for PKC. We show that PKCϵ can directly phosphorylate Ser779 in vitro, whereas PKC activation (PMA) or PKCϵ overexpression increases Ser779 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). Furthermore, PKC inhibition (GF109203X) or PKCϵ siRNA-mediated knockdown blocks Ser779 phosphorylation (Figs. 6 and 7). Importantly, the phosphorylation of Ser779 by PKCϵ is required for the maximal activation of Ras/MAPK signaling and neuronal differentiation of PC12 and BMSCs in response to growth factor (Figs. 6 and 7). Others have shown that PKCϵ overexpression enhances PC12 differentiation in response to NGF and EGF (37), whereas our previous studies identified conserved putative phosphoserine 14-3-3 binding sites in the C-terminal tails of members of the NGF and EGF receptor families (18), raising the possibility that PKC may phosphorylate other growth factor receptors to promote Ras/MAPK signaling.

Gene knock-out studies in mice have shown that FGF2 is important for neurogenesis of the neocortex during development, as well as the differentiation of neuroprogenitor cells following injury (38, 39). PKCϵ has also been proposed to play key roles in neurogenesis through the regulation of Ras/MAPK signaling in both Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian cells (40, 41). Furthermore, pharmacological activation of PKC using bryostatin is neuroprotective in a rat model of ischemic stroke (42). Thus, PKCϵ may play important roles in neural regeneration, not only through its ability to regulate canonical downstream Ras/MAPK targets but also through its ability to phosphorylate growth factor receptors such as FGFR and promote neuronal survival and differentiation. In fact, PKCϵ signaling has been shown in a number of studies to have pro-survival outcomes, suggesting that it might be a therapeutic target for enhancing neural regeneration after injury (43).

Phosphotyrosine signaling pathways are clearly important for regulating FGFR-mediated cellular responses. Others have shown that an FGFR1 mutant that is defective in tyrosine kinase activity (FGFR-Y653/654F) is unable to promote differentiation when expressed in PC12 cells (9). Inversely, an FGFR mutant in which Tyr653 and Tyr654 remain intact while the remaining 13 tyrosine residues were mutated also resulted in defective PC12 differentiation (9). Although mutation of Ser779 does not affect FGFR2 tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 4), inhibition of FGFR tyrosine phosphorylation with SU5402 blocks Ser779 phosphorylation and the differentiation of both PC12 (data now shown) and BMSCs (Fig. 7B), indicating that the ability of Ser779 to promote PC12 differentiation requires FGFR tyrosine kinase activity. It is possible that the C2 phosphotyrosine-binding domain of PKCϵ might be important for its recruitment to phosphotyrosine docking sites either on FGFR or associated proteins leading to ERK1/2 signaling (44). Furthermore, PKCϵ activation is regulated in a diacylglycerol-dependent but calcium-independent manner. Thus, the production of diacylglycerol by PLCγ following FGFR tyrosine phosphorylation could also provide a necessary step in PKCϵ activation and Ser779 phosphorylation. Future work examining how phosphoserine and phosphotyrosine signaling events intersect at the level of FGFRs will be important for understanding how multiple pathways are integrated to allow specificity in signaling and cellular responses.

There are greater than 200 type I growth factor and cytokine receptors described, with many demonstrating distinct and sometimes opposing biological activities (45). However, despite their functional diversity, many growth factor and cytokine receptors appear to activate a limited repertoire of overlapping pathways (45). The duration or strength of signals generated downstream of cell surface receptors has been proposed to explain how independent and distinct cellular responses can arise from the activation of common (or redundant) downstream pathways. Through either negative or positive feedback loops, the Raf-1-MEK-ERK module is wired in such a way that it can generate signaling outputs across a range of amplitudes and kinetics depending on the specific signaling inputs from upstream receptors (33). In addition to the prototypic example of sustained versus transient ERK activation regulating distinct and independent outcomes in PC12 cells (6), many other examples in which quantitative differences in ERK signaling lead to qualitative differences in cellular responses have been reported and include thymocyte positive and negative selection, as well as yeast mating pathways (46, 47). Thus, growth factor receptors can provide instructive signals that determine whether downstream signaling is sustained or transient, thereby dictating cellular outcomes. The ability to provide such instructive signals would imply that at least some growth factor receptors may have unique intrinsic features that allow them to generate specific signals and biological responses. In some cases such as the c-Kit and Met receptors, specific phosphotyrosine motifs have been functionally linked to distinct cellular responses and provide one such mechanism by which pleiotropic responses can be controlled (48, 49). However, for other receptors including the FGFRs, significant redundancy in phosphotyrosine signaling has been observed, and it has been difficult to functionally link individual receptor tyrosine residues to the regulation of different cellular responses (9, 50, 51). Our findings now demonstrate that growth factor receptor serine phosphorylation can also provide specificity in signaling to control pleiotropic biological responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Bradshaw (University of California, San Francisco), Dr. Bagheri-Fam (Prince Henry's Institute), and Dr. Suzuki (Yokohama, Japan) for reagents. We thank Gafar Sarvestani and Emma Barry for expert technical assistance and Quenten Schwarz and Angel Lopez (South Australia (SA) Pathology) for helpful advice.

This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and by funds from the Victorian Government Operational Infrastructure Support Scheme to St. Vincent's Institute.

- FGFR

- FGF receptor

- BMSC

- bone marrow stromal cell

- PLCγ

- phospholipase Cγ

- pAb

- polyclonal antibody

- RBD

- Ras-binding domain

- nPKC

- novel PKC

- HS

- horse serum

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- cPKC

- conventional PKC.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eswarakumar V. P., Lax I., Schlessinger J. (2005) Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dailey L., Ambrosetti D., Mansukhani A., Basilico C. (2005) Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 233–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ong S. H., Hadari Y. R., Gotoh N., Guy G. R., Schlessinger J., Lax I. (2001) Stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by fibroblast growth factor receptors is mediated by coordinated recruitment of multiple docking proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6074–6079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mohammadi M., Dikic I., Sorokin A., Burgess W. H., Jaye M., Schlessinger J. (1996) Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 977–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Furdui C. M., Lew E. D., Schlessinger J., Anderson K. S. (2006) Autophosphorylation of FGFR1 kinase is mediated by a sequential and precisely ordered reaction. Mol. Cell 21, 711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall C. J. (1995) Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell 80, 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaudry D., Stork P. J., Lazarovici P., Eiden L. E. (2002) Signaling pathways for PC12 cell differentiation. Making the right connections. Science 296, 1648–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raffioni S., Thomas D., Foehr E. D., Thompson L. M., Bradshaw R. A. (1999) Comparison of the intracellular signaling responses by three chimeric fibroblast growth factor receptors in PC12 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7178–7183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Foehr E. D., Raffioni S., Murray-Rust J., Bradshaw R. A. (2001) The role of tyrosine residues in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signaling in PC12 cells. Systematic site-directed mutagenesis in the endodomain. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37529–37536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin H. Y., Xu J., Ischenko I., Ornitz D. M., Halegoua S., Hayman M. J. (1998) Identification of the cytoplasmic regions of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 1 which play important roles in induction of neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by FGF-1. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 3762–3770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mohammadi M., Dionne C. A., Li W., Li N., Spivak T., Honegger A. M., Jaye M., Schlessinger J. (1992) Point mutation in FGF receptor eliminates phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis without affecting mitogenesis. Nature 358, 681–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spivak-Kroizman T., Mohammadi M., Hu P., Jaye M., Schlessinger J., Lax I. (1994) Point mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor eliminates phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis without affecting neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14419–14423 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peruzzi F., Prisco M., Dews M., Salomoni P., Grassilli E., Romano G., Calabretta B., Baserga R. (1999) Multiple signaling pathways of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in protection from apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 7203–7215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oksvold M. P., Huitfeldt H. S., Langdon W. Y. (2004) Identification of 14-3-3ζ as an EGF receptor interacting protein. FEBS Lett. 569, 207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olayioye M. A., Guthridge M. A., Stomski F. C., Lopez A. F., Visvader J. E., Lindeman G. J. (2003) Threonine 391 phosphorylation of the human prolactin receptor mediates a novel interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32929–32935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takala H., Nurminen E., Nurmi S. M., Aatonen M., Strandin T., Takatalo M., Kiema T., Gahmberg C. G., Ylanne J., Fagerholm S. C. (2008) β2 integrin phosphorylation on Thr758 acts as a molecular switch to regulate 14-3-3 and filamin binding. Blood 112, 1853–1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guthridge M. A., Stomski F. C., Barry E. F., Winnall W., Woodcock J. M., McClure B. J., Dottore M., Berndt M. C., Lopez A. F. (2000) Site-specific serine phosphorylation of the IL-3 receptor is required for hemopoietic cell survival. Mol. Cell 6, 99–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lonic A., Barry E. F., Quach C., Kobe B., Saunders N., Guthridge M. A. (2008) Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 phosphorylation on serine 779 couples to 14-3-3 and regulates cell survival and proliferation. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 3372–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guthridge M. A., Barry E. F., Felquer F. A., McClure B. J., Stomski F. C., Ramshaw H., Lopez A. F. (2004) The phosphoserine-585-dependent pathway of the GM-CSF/IL-3/IL-5 receptors mediates hematopoietic cell survival through activation of NF-κB and induction of Bcl-2. Blood 103, 820–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang H., Xia Y., Lu S. Q., Soong T. W., Feng Z. W. (2008) Basic fibroblast growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation of mouse bone marrow stromal cells requires FGFR-1, MAPK/ERK, and transcription factor AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5287–5295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Powell J. A., Thomas D., Barry E. F., Kok C. H., McClure B. J., Tsykin A., To L. B., Brown A., Lewis I. D., Herbert K., Goodall G. J., Speed T. P., Asou N., Jacob B., Osato M., Haylock D. N., Nilsson S. K., D'Andrea R. J., Lopez A. F., Guthridge M. A. (2009) Expression profiling of a hemopoietic cell survival transcriptome implicates osteopontin as a functional prognostic factor in AML. Blood 114, 4859–4870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Molzan M., Ottmann C. (2012) Synergistic binding of the phosphorylated S233- and S259-binding sites of C-RAF to one 14-3-3ζ dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 423, 486–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bae J. H., Lew E. D., Yuzawa S., Tomé F., Lax I., Schlessinger J. (2009) The selectivity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling is controlled by a secondary SH2 domain binding site. Cell 138, 514–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muslin A. J., Tanner J. W., Allen P. M., Shaw A. S. (1996) Interaction of 14-3-3 with signaling proteins is mediated by the recognition of phosphoserine. Cell 84, 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang X., Ibrahimi O. A., Olsen S. K., Umemori H., Mohammadi M., Ornitz D. M. (2006) Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15694–15700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schüller A. C., Ahmed Z., Ladbury J. E. (2008) Extracellular point mutations in FGFR2 result in elevated ERK1/2 activation and perturbation of neuronal differentiation. Biochem. J. 410, 205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cross M. J., Lu L., Magnusson P., Nyqvist D., Holmqvist K., Welsh M., Claesson-Welsh L. (2002) The Shb adaptor protein binds to tyrosine 766 in the FGFR-1 and regulates the Ras/MEK/MAPK pathway via FRS2 phosphorylation in endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2881–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsson H., Klint P., Landgren E., Claesson-Welsh L. (1999) Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1-mediated endothelial cell proliferation is dependent on the Src homology (SH) 2/SH3 domain-containing adaptor protein Crk. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25726–25734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schönwasser D. C., Marais R. M., Marshall C. J., Parker P. J. (1998) Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 790–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corbit K. C., Foster D. A., Rosner M. R. (1999) Protein kinase Cδ mediates neurogenic but not mitogenic activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in neuronal cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 4209–4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wooten M. W., Zhou G., Seibenhener M. L., Coleman E. S. (1994) A role for ζ protein kinase C in nerve growth factor-induced differentiation of PC12 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 5, 395–403 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martiny-Baron G., Kazanietz M. G., Mischak H., Blumberg P. M., Kochs G., Hug H., Marmé D., Schächtele C. (1993) Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Gö 6976. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9194–9197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Santos S. D., Verveer P. J., Bastiaens P. I. (2007) Growth factor-induced MAPK network topology shapes Erk response determining PC-12 cell fate. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zheng Y., Liu H., Coughlin J., Zheng J., Li L., Stone J. C. (2005) Phosphorylation of RasGRP3 on threonine 133 provides a mechanistic link between PKC and Ras signaling systems in B cells. Blood 105, 3648–3654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pardo O. E., Wellbrock C., Khanzada U. K., Aubert M., Arozarena I., Davidson S., Bowen F., Parker P. J., Filonenko V. V., Gout I. T., Sebire N., Marais R., Downward J., Seckl M. J. (2006) FGF-2 protects small cell lung cancer cells from apoptosis through a complex involving PKCϵ, B-Raf and S6K2. EMBO J. 25, 3078–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kolch W., Heidecker G., Kochs G., Hummel R., Vahidi H., Mischak H., Finkenzeller G., Marmé D., Rapp U. R. (1993) Protein kinase Cα activates RAF-1 by direct phosphorylation. Nature 364, 249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brodie C., Bogi K., Acs P., Lazarovici P., Petrovics G., Anderson W. B., Blumberg P. M. (1999) Protein kinase Cϵ plays a role in neurite outgrowth in response to epidermal growth factor and nerve growth factor in PC12 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 10, 183–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ortega S., Ittmann M., Tsang S. H., Ehrlich M., Basilico C. (1998) Neuronal defects and delayed wound healing in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5672–5677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yoshimura S., Takagi Y., Harada J., Teramoto T., Thomas S. S., Waeber C., Bakowska J. C., Breakefield X. O., Moskowitz M. A. (2001) FGF-2 regulation of neurogenesis in adult hippocampus after brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5874–5879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shirai Y., Adachi N., Saito N. (2008) Protein kinase Cϵ. Function in neurons. FEBS Journal 275, 3988–3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hyde R., Corkins M. E., Somers G. A., Hart A. C. (2011) PKC-1 acts with the ERK MAPK signaling pathway to regulate Caenorhabditis elegans mechanosensory response. Genes Brain Behav. 10, 286–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sun M. K., Hongpaisan J., Alkon D. L. (2009) Postischemic PKC activation rescues retrograde and anterograde long-term memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14676–14680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nelson T. J., Alkon D. L. (2009) Neuroprotective versus tumorigenic protein kinase C activators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Benes C. H., Wu N., Elia A. E., Dharia T., Cantley L. C., Soltoff S. P. (2005) The C2 domain of PKCδ is a phosphotyrosine binding domain. Cell 121, 271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guthridge M. A., Lopez A. F. (2007) Phosphotyrosine/phosphoserine binary switches. A new paradigm for the regulation of PI3K signalling and growth factor pleiotropy? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 250–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McNeil L. K., Starr T. K., Hogquist K. A. (2005) A requirement for sustained ERK signaling during thymocyte positive selection in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13574–13579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sabbagh W., Jr., Flatauer L. J., Bardwell A. J., Bardwell L. (2001) Specificity of MAP kinase signaling in yeast differentiation involves transient versus sustained MAPK activation. Mol. Cell 8, 683–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kissel H., Timokhina I., Hardy M. P., Rothschild G., Tajima Y., Soares V., Angeles M., Whitlow S. R., Manova K., Besmer P. (2000) Point mutation in kit receptor tyrosine kinase reveals essential roles for kit signaling in spermatogenesis and oogenesis without affecting other kit responses. EMBO J. 19, 1312–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maina F., Panté G., Helmbacher F., Andres R., Porthin A., Davies A. M., Ponzetto C., Klein R. (2001) Coupling Met to specific pathways results in distinct developmental outcomes. Mol. Cell 7, 1293–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fambrough D., McClure K., Kazlauskas A., Lander E. S. (1999) Diverse signaling pathways activated by growth factor receptors induce broadly overlapping, rather than independent, sets of genes. Cell 97, 727–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guthridge M. A., Seldin M., Basilico C. (1996) Induction of expression of growth-related genes by FGF-4 in mouse fibroblasts. Oncogene 12, 1267–1278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]