Abstract

Background:

The definition of health for people with cancer is not focused solely on the physiology of illness and the length of life remaining, but is also concerned with improving the well-being and the quality of the life (QOL) remaining to be lived. This study aimed to identify the constructs most associated with QOL in people with advanced cancer.

Methods:

Two hundred three persons with recent diagnoses of different advanced cancers were evaluated with 65 variables representing individual and environmental factors, biological factors, symptoms, function, general health perceptions and overall QOL at diagnosis. Three independent stepwise multiple linear regressions identified the most important contributors to overall QOL. R2 ranking and effect sizes were estimated and averaged by construct.

Results:

The most important contributor of overall QOL for people recently diagnosed with advanced cancer was social support. It was followed by general health perceptions, energy, social function, psychological function and physical function.

Conclusions:

We used effect sizes to summarise multiple multivariate linear regressions for a more manageable and clinically interpretable picture. The findings emphasise the importance of incorporating the assessment and treatment of relevant symptoms, functions and social support in people recently diagnosed with advanced cancer as part of their clinical care.

Keywords: quality of life, regression, effect size

Cancer will develop in 45% of men and 40% of women during their lifetime, and about 1 in 4 will die of the disease (Marrett et al, 2008). The survival rates for most tumours are, however, continually improving owing to earlier detection, continued improvement in treatment therapies and better general medical management (Marrett et al, 2008). Owing to its improved survival, cancer is now considered a chronic disease (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, 2010), and as a result, concerns about the well-being and the quality of life (QOL) of people with cancer has become paramount in clinical research (Food and Drug Administration, 2006). Health-care professionals are also becoming increasingly exposed to the benefits of assessing QOL in daily clinical practice. But the understanding of the scientific basis underlying QOL assessment still needs to be established (Osoba, 2007).

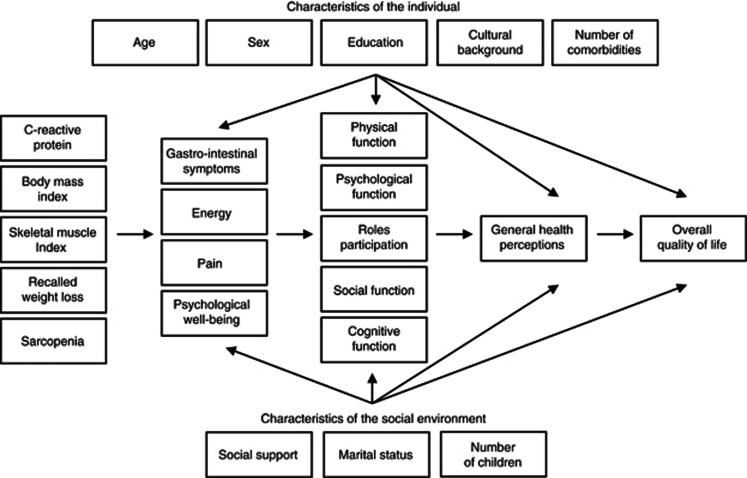

A comprehensive model of health-related QOL (HRQL) was developed by Wilson and Cleary (1995). This conceptual model suggests causal links among biological and physiological factors, symptoms, functional levels, general health perceptions and overall QOL. Individual and environmental characteristics also influence each of the components of the model (Wilson and Cleary, 1995). The Wilson and Cleary Model of HRQL for people with cancer can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Wilson and Cleary model of health-related quality of life in people with advanced cancer.

The Wilson and Cleary model was partly assessed for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding (Sousa and Williamson, 2003), Parkinson's disease (Straits-Troster et al, 2000; Chrischilles et al, 2002), heart disease (Bennett et al, 2001; Heo et al, 2005; Lee et al, 2005a; Mathisen et al, 2007), HIV/AIDS (Wilson and Cleary, 1996, 1997; Sousa et al, 1999; Cosby et al, 2000; Hays et al, 2000; Sousa and Chen, 2002; Cunningham et al, 2005; Sousa and Kwok, 2006), renal disease (Molzahn et al, 1996). It was minimally examined in people with cancer, as only one study examined the model with survivors with Hodgkin's lymphoma (Wettergren et al, 2004).

The purpose of this study was therefore to estimate, for people with a newly diagnosed advanced cancer, the extent to which biological and physiological factors, symptoms, function and general health perceptions predict overall QOL, as hypothesised by the Wilson and Cleary Model of HRQL.

Material and methods

Participants

Adults were recruited if they have had a recent diagnosis of advanced cancer and had been referred to the McGill University Health Center or the Jewish General Hospital oncology clinics, in Montreal, Canada. Advanced cancer was defined as unresectable stage 3A, 3B or 4 non-small-cell lung cancer; stage 3 or 4 upper gastrointestinal cancer; stage 4 colorectal, hepatobilliary or head and neck cancers; breast and prostate cancers with visceral metastases; and all stages of pancreatic cancers. The inclusion criterion included an estimated life expectancy of 3 months or more and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Score of 0 to 3 to represent varying degrees of disabilities but sufficient function to complete the assessments (Oken et al, 1982). Patients were not eligible if they were unable to comply with study instructors or if they had symptomatic brain metastases.

Procedure

The study was approved by the hospitals' Institutional Review Board. The eligibility of patients was verified by a member of their primary oncology team who also obtained verbal consent to be approached by study personnel. If patients consented to participate, an appointment was made for the assessment. At their first assessment, participants were assessed using patient-reported outcomes and direct measures representing the domains of the Wilson and Cleary conceptual model of HRQL. If patients refused to participate, sociodemographic information such as their age, their primary tumour origin and their gender were collected, as were their self-perceived health from 0 to 10. This was done to estimate whether there was a sampling bias between participants and non-participants.

Measurement

The measurement strategy included characterising the sample and selecting relevant items and domains from widely used health outcomes measures in cancer.

The outcome of interest in this study was the construct of overall QOL. One subscale and two single items were used to represent overall QOL: the existential domain of the McGill Quality Of Life Questionnaire (MQOL-existential), the single-item scale of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL-SIS) and the QOL item of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (first version) (ESAS-QOL).

Fifty-seven explanatory variables and eight potential confounder variables were included in the analyses. The variables were chosen to represent the different domains of the Wilson and Cleary model. The measures used and their psychometric properties are fully described in the Appendices A and B (Table A1 and A2), recognising that the individual items and subscales were the elements used in the analyses.

Table A1. Description and Psychometric Properties of the Measures.

| Measure | Description of measure | Psychometric properties |

|---|---|---|

| McGill QOL Questionnaire (MQOL) |

The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL) was designed to measure QOL at

all stages of a life-threatening illness, from diagnosis to cure or death (Cohen

et al, 1995, 1996b, 1997, 2001; Cohen and Mount, 2000). It comprises 16

self-report items that are rated on a scale of 0 (the worst) to 10 (the best) and

based on a two-day time frame. Five domains (physical symptoms, psychological

symptoms, existential well-being, physical well-being and support) are computed from

the score or the mean scores of 1 to 6 items. In addition, the MQOL includes a

single-item scale (MQOL-SIS), also scored from 0 to 10, and constructed to measure

overall QOL. |

Good levels of reliability and validity in people with cancer (Cohen et

al, 1995; 1996b, 1997, 2001; Cohen and Mount, 2000). Construct validity and

internal consistency reliability of the domains was demonstrated in other palliative

populations as well (Cohen et al, 1996a, 1997). |

| Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS) |

The ESAS is a 10-item symptom visual analogue scale (VAS) developed for use in

symptom assessment of palliative care patients (Richardson and Jones, 2009). The

patients rate the severity of the following nine symptoms: pain, fatigue, nausea,

depression, anxiety, drowsiness, lack of appetite, itching and shortness of breath

on a 10-cm line. The severity for each symptom is rated from 0 to 10, 0 being an

absent symptom and 10 being of the worst possible severity. There is an additional

VAS assessing quality of life. |

An acceptable level of validity and reliability of the measure has been

reported (Chang et al, 2000; Nekolaichuk et al, 2008; Richardson

and Jones, 2009). |

| Preference-based cancer index (PBCI) |

The Preference-based cancer index is an adaptation from the preference-based

stroke index, a collection of items intended to supplement the EQ-5D index (Poissant

et al, 2003). It includes 10 items with a three-point Likert-type

response scale assessing walking, climbing stairs, physical activities/sports,

recreational activities, work, driving, speech, memory, coping and self-esteem. A

cumulative score can be obtained from these preference weights (Poissant et

al, 2003). |

Content validity and construct validity of the measure has been demonstrated

(Poissant et al, 2003). |

| Functional assessment of anorexia/cachexia therapy (FAACT) |

The FAACT consists of 27 Likert-type items of the symptoms associated with

cancer and its treatments, scored from 0 to 4 anchored with ‘not at all'

to ‘very much', with total quality of life score ranging from 0 to 108.

The FAACT includes the FACT-G, with an additional 12 items of ‘additional

concerns' that refer to problems related to cachexia or anorexia (Ribaudo

et al, 2000). In our assessment, we only included the 12 items relating

to the cachexia/anorexia symptoms. |

Reliability and validity of the FACT and the FAACT measurement system have been

recognised (Ribaudo et al, 2000). |

| RAND short form 36-item health survey (RAND-36)—version 1 |

The RAND-36 is a generic health-related quality of life measure that assesses 8

health concepts: physical and social function, usual roles activities, pain,

vitality, mental health, and perception of health in general. Each item is scored on

a dichotomous, three or five-point categorical scale; subscale scores range from 0

to 100. Physical and mental summary scores can also be constructed (Hays et

al, 1993). |

Reliability, validity and responsiveness have been largely demonstrated in

patients with a variety of acute and chronic conditions (Hays et al, 1993;

Wood-Dauphinee et al, 1998). |

| EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) |

The EQ-5D comprises two sections, the EQ-5Dindex and the EQ-5DVAS. The

EQ-5Dindex is a 5-item standardized generic measure of HRQL measuring mobility,

self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression with a

three-point response scale. The EQ-5DVAS is a 0–100 thermometer scale that

assesses self-perceived health status. |

It has been widely used in studies of people with cancer (Norum, 1996) and it

yields comparable results to other well-known measures (de Haan et al,

1993; Goodyear and Fraumeni, 1996; Norum, 1996). |

| Taste and smell indicators (TSI) |

The taste and smell indicators (TSI) consist of two single-item indicators

asking for disturbances in smell and in taste, with a three-point Likert-type

response scales associated with the anchors ‘no disturbances',

‘moderate disturbances' and ‘severe disturbances or cannot

smell/taste at all'. |

It yields comparable results to other well-known measures (de Haan et

al, 1993; Goodyear and Fraumeni, 1996; Norum, 1996). |

| Word and digit recall questions (WDR) |

To assess visual memory, we derived the word recall question from the delayed

word recall test, a test originally developed to facilitate the early diagnosis of

Alzheimer's disease (O'Carroll et al, 1997). The digit sequence

learning test is a test of attention, short-term memory, and associative learning

(Benton et al, 1983). Subjects are asked to repeat a string of digits

immediately after hearing them, first in direct and then in reverse order. The total

number of correctly repeated digit string sequences was tallied. |

|

| Multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) |

The Multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) is a 20-item self-report measure

of fatigue with five dimensions: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue,

reduced motivation and reduced activity, and 4 items per dimension, each scored from

1 to 5. The total score ranges from 4 to 20, a higher score indicating more

fatigue. |

The measure was evaluated with cancer patients receiving radiotherapy and was

found to have good internal consistency, construct validity and convergent validity

(Smets et al, 1995; Schneider, 1998; Meek et al, 2000; Fillion

et al, 2003). |

| Modified ‘community healthy activities model program for seniors physical

activity measure' (modified CHAMPS) |

The CHAMPS is a self-report measure of physical activity, comprising 40

activities evaluated according to the total number of hours of activity done in the

past week. We used a modified version of the CHAMPS resulting in the physical

activities done in the past week in total hours. The numbers of hours and the type

of category was then transformed into a respective mean metabolic equivalent (MET)

intensity level (Ainsworth et al, 2000). |

The measure has been shown to be reliable, valid and responsive in the elderly

in the community (Stewart et al, 2001a, 2001b). |

| Six minute walk test (6MWT) |

The 6 min walk test (6MWT) is a submaximal functional test of walking

endurance (Solway et al, 2001). The distance walked was recorded both at

the first 2 min and for the full duration of the test at 6 min. The

data included here are for the test at 2 min to maximise the data obtained,

as some fragile patients could not complete the six minutes of the test. |

The 6MWT has been evaluated in several different populations and is a valid and

reliable measure (Solway et al, 2001). |

| Timed ‘up and go' (TUG) |

The timed up and go is a quick and practical test of basic mobility skills

suitable for frail elderly persons. The score, is the time, in seconds, taken to

stand up from a chair, walk 3 m back-and-forth, and sit down. Higher scores

indicate greater impairment of mobility. |

Concurrent validity (Podsiadlo and Richardson, 1991; Venturini et al,

1995) has been demonstrated with correlations with gait speed, walking speed

r=0.71–0.96), the Berg balance scale, and the Barthel index

(r=−0.51). |

| Walking speed | Gait speed is a physical characteristic derived from directly measuring the parameters of distance and time. It has been associated with strength of the affected lower extremity, cadence and stride length, balance, degree of lower extremity motor recovery, and functional mobility (Holden et al, 1986). Standardized instructions are to walk at a ‘comfortable' or ‘maximum' speed along a walkway typically ranging from 2 to 20 m (Fransen et al, 1997). In this study, we instructed patients to walk at a comfortable pace speed over a distance of 10 m, and the time taken to complete the middle 5 m distance was recorded. | Gait speed is considered a valid measure of walking ability as it correlates with functional mobility, degree of independence in walking, and many different gait parameters (Holden et al, 1986; Nakamura et al, 1988; Fransen et al, 1997). |

Table A2. Classification of Variables and Constructs Measured.

| Outcome variables | Construct measured | Measurement scale | Units/properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| MQOL-SIS—stand alone item |

Quality of life |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, higher is better |

| MQOL-existential domain |

Quality of life |

Continuous |

Mean score of 6 items, scale 0–10, higher is better |

| ESAS-QOL item |

Quality of life |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

|

Exposure variables

|

Construct measured

|

Measurement scale

|

Original units/properties*

|

|

Biological variables

| |||

| Body mass index |

Muscle wasting |

Continuous |

kgm−2 |

| Skeletal muscle index (skeletal muscle mass/total mass x

100%) |

Muscle wasting |

Continuous |

% |

| Sarcopenia |

Muscle wasting |

Continuous |

No; yes |

| C-reactive protein |

Systemic inflammation |

Continuous |

mgl−1 |

| Recalled weight loss |

Recent weight loss |

Categorical |

None; 2–5% >5% |

|

Symptoms

| |||

|

Gastrointestinal symptoms

| |||

| Faact o2 |

Vomiting |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–4 scale, higher is worse |

| ESAS nausea |

Nausea |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

| ESAS appetite |

Appetite |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

| Faact c6 |

Appetite |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–4 scale, higher is better |

| Faact act6 |

Interest in food |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–4 scale, higher is worse |

| Faact act7 |

Difficulty eating rich food |

Categorical—ordinal l |

0–4 scale, higher is worse |

| Faact act10 |

Getting full easily |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–4 scale, higher is worse |

|

Taste and smell

| |||

| Taste item |

Taste |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| Smell item |

Smell |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| Faact act 3 |

Taste |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–4 scale, higher is worse |

|

Pain

| |||

| ESAS pain |

General pain |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

| EQ-5D pain |

General pain |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| Faact act 11 |

Stomach pain |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–4 scale, higher is worse |

| RAND-36—pain subscale |

General pain |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

|

Fatigue

| |||

| ESAS fatigue |

Fatigue |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

| MFI—general fatigue subscale |

Fatigue |

Continuous |

4–20 subscale, higher is worse |

| RAND-36—vitality subscale |

Energy |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

|

Psychological symptoms

| |||

| MQOL—psychological domain |

Nervousness, being afraid, depressed, sad |

Continuous |

Mean score of 4 items, 0–10, higher is better |

| ESAS depression |

Depression |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

| ESAS anxiety |

Anxiety |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS scale, lower is better |

| EQ-5D depression/anxiety |

Depression/anxiety |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| RAND-36—mental health subscale (MHI) |

Nervousness, being calm, depressed, ‘blue', happy |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

|

Cognition and concentration

| |||

| Word recall |

Memory |

Continuous |

0–5, higher is better |

| Mental reversal |

Concentration |

Continuous |

0–5, higher is better |

| Delayed recall |

Memory |

Continuous |

0–5, higher is better |

| Digit series repeats forward |

Memory/concentration |

Continuous |

0–16, higher is better |

| Digit series repeats backwards |

Memory/concentration |

Continuous |

0–16, higher is better |

| PBCI memory |

Memory |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| MFI—mental fatigue |

Concentration |

Continuous |

4–20 subscale, higher is worse |

|

FUNCTION

| |||

|

Physical function

| |||

| EQ-5D mobility |

Mobility |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| EQ-5D self-care |

Self-care |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| EQ-5D usual activities |

Usual activities |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| MFI—physical fatigue |

Physical function |

Continuous |

4–20 subscale, higher is worse |

| RAND-36—physical function subscale |

Physical function |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

| MFI—reduced activity |

Physical activities |

Continuous |

4–20 subscale, higher is worse |

| PBCI—Function Subscale (mean score of 5 items) |

Walking, stairs, participating in demanding activities, work, driving |

Continuous |

0–2 subscale, higher is worse |

| 2 MWT distance |

Functional walking capacity |

Continuous |

Metres |

| TUG |

Basic mobility |

Continuous |

Seconds |

| Comfortable gait speed |

Walking ability |

Continuous |

Metres/seconds |

| Average METS per week |

Average weekly activity level |

Continuous |

METS |

|

Psychological function

| |||

| PBCI coping |

Coping |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| PBCI self-esteem |

Self-esteem |

Categorical—ordinal |

0–2 scale, higher is worse |

| MFI—reduced motivation subscale |

Desire to engage in activities |

Continuous |

4–20 subscale, higher is worse |

|

Social function

| |||

| RAND-36—social subscale |

Social function |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

|

Role function

| |||

| RAND-36—role emotional subscale |

Role function |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

| RAND-36—role physical subscale |

Role function |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

|

General health perception

| |||

| EQ-5D VAS |

GHP |

Continuous |

0–100 VAS, higher is better |

| RAND-36—GHP Subscale |

GHP |

Continuous |

0–100 scale, higher is better |

| MQOL—physical well-being |

Physical health perception |

Continuous |

0–10 VAS, higher is better |

|

Potential confounding variables

|

Construct measured

|

Measurement scale

|

Units/properties

|

|

Individual characteristics

| |||

| Sex |

Sex |

Binary |

0=female |

| |

|

|

1=male |

| Age |

Age |

Continuous |

Years |

| Number of comorbidities |

Comorbidities |

Considered continuous |

1–7, Higher number indicates more |

|

Individual characteristics (continued)

| |||

| Cancer type |

Primary tumour site |

Categorical—ordinal |

Eight main tumour sites |

| Educational level |

Proxy to Socio-economical status |

Categorical—ordinal |

Eight levels corresponding to highest degree obtained |

| Nationality |

Cultural influence |

Categorical—nominal |

Country of birth |

|

Social support characteristics

| |||

| Marital status |

Social support |

Categorical—nominal |

Six marital statuses |

| Number of children |

Social support |

Continuous |

Number of children |

| Someone they can trust and confide in |

Social support |

Binary |

No; yes |

| Someone who would be able to provide help as long as they would need it |

Social support |

Binary |

No; yes |

| MQOL-support domain | Social support | Continuous | Mean score of two items, 0–10, higher is better |

Abbreviations: ESAS=edmonton symptom assessment system (original version); EQ-5D=EuroQoL-5D; Faact=functional assessment of anorexia/cachexia therapy; MFI=multidimensional fatigue inventory; MQOL=McGill quality of life questionnaire; PBCI=preference-based cancer index; RAND-36=RAND short form 36-item health survey (RAND-36)—version 1; VAS=visual analogue scales.

Some of the items of the Facct and the MFI, as well as all items of the ESAS, the EQ-5Dindex, the PBCI, and the taste and smell items were rescored so that a higher score indicates better health status.

Rescoring for some variables took place after the examination of the frequencies to account for categories with no or little observations.

Biological and physiological indicators were also collected. These included C-reactive protein serum concentration levels, recent recalled weight loss at the time of diagnosis, the body mass index, the skeletal muscle index and the presence of sarcopenia.

In addition, personal factors such as age, sex, the site of the original tumour, the number of comorbidities, the highest level of education completed and the country of birth were recorded on the day of testing. Social environmental characteristics were also collected, such as the marital status and the number of children.

Statistical methods

Three different subscale/items (MQOL-existential, MQOL-SIS and ESAS-QOL) represented the outcome construct, overall QOL. Consequently, three independent analyses were performed to determine the most important contributors of overall QOL.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the participants and the distribution of variables. Mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables, as well as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, summarised patients' characteristics. Age, sex, primary tumour site, years of education, cultural origin, number of comorbidities, number of children and marital status were examined for their potential for confounding.

Univariate linear regressions were used to screen the associations between the 57 potential contributors to each representation of overall QOL. Variables that were associated with one of the QOL measures at P-value below or equal the 0.1 level were retained for the further analyses.

Bivariate correlations between the retained variables and the outcomes were examined using Pearson, polychoric and polyserial correlation coefficients. All assumptions of linear regression were examined, and there were no serious violations.

Three independent forward stepwise multiple linear regressions were performed to predict overall QOL. The 10 variables explaining the most variability per outcome were ranked by partial R2 order. Effect sizes were also estimated for these variables using t-values (Cohen, 1988; Liang et al, 1990), which is a quantitative similar to Cohen's d. In the context of linear regression, the t-value corresponds to the difference in least-squares estimators divided by the standard error of the least-squares estimators. In an attempt to identify constructs with more consistent associations with overall QOL, the partial R2 rankings and effect sizes of the identified contributing variables were averaged per construct and across all three outcomes of overall QOL.

Stepwise multiple linear regression is an analytical approach that has the capacity to select a statistical model ‘when there is a large number of potential explanatory variables and no underlying theory on which to base the model selection' (Pace, 2008). This automatism of the procedure has been previously described as its limitation. However, in this study, the Wilson and Cleary theoretical model of HQOL directed the selection of the variables included in the analyses. Also, this statistical approach has the advantage of preventing bias imposed by the investigators upon the selection of final model.

All statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Analysis Systems version 9.2.

Results

Description of the sample

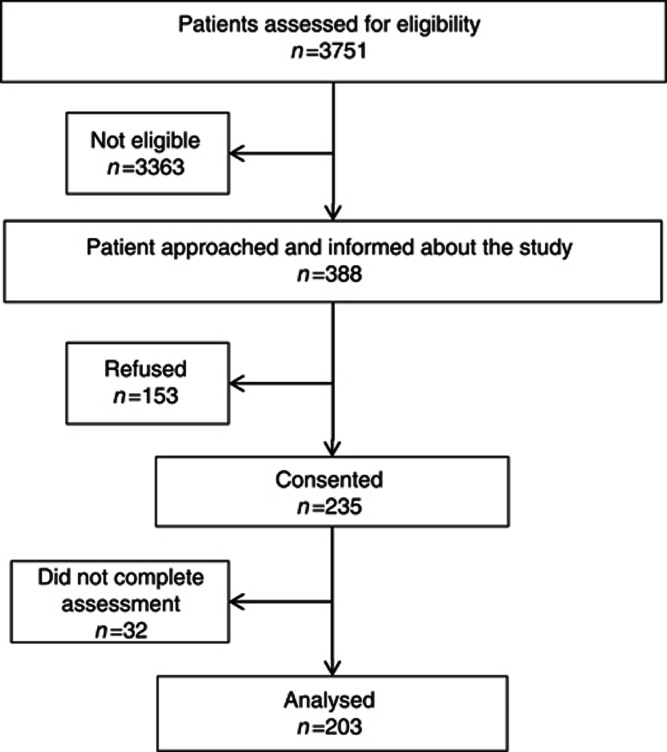

Three thousand seven hundred fifty one patients were screened for eligibility. Of the 388 eligible patients, 203 patients (52.3%) consented to participate and completed the initial evaluation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart.

The average age was 63 years (±13) and 59.3% of participants were men. The most common primary tumour origins were the pancreas (22.6%), followed by lung (16.7%), and the colorectal tract (12.3%). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristic | Participants ( n =203), (%) |

|---|---|

|

Age (years) categories (mean: 63.3, s.d. 12.9)

| |

| <35 | 7 (3.3) |

| 36–50 | 23 (11.3) |

| 51–64 | 72 (35.3) |

| ⩾65 |

101 (49.8) |

|

Sex

| |

| ♂/♀ | 120/83 |

| % |

59.9/40.9 |

|

Primary tumour site

| |

| Pancreatic | 46 (22.6) |

| Lung | 34 (16.7) |

| Colorectal | 25 (12.3) |

| Upper GI | 23 (11.3) |

| ENT | 23 (11.3) |

| Breast | 20 (9.8) |

| Hepatobilliary | 17 (8.3) |

| Prostate | 7 (3.4) |

| Urological | 3 (1.5) |

| Unconfirmed primary origin | 2 (1.0) |

| Ovarian | 1 (0.5) |

| Retroperitoneal | 1 (0.5) |

| Skin—basal cell |

1 (0.5) |

|

Number of comorbidities (mean 2.4, s.d. 1.5)

| |

| 0 (Cancer only) | 74 (36.5) |

| 1 | 51 (25.1) |

| ⩾2 | 78 (38.4) |

Abbreviations: GI=gastrointestinal; s.d.=standard deviation

Sociodemographic information was collected from 157 patients who refused to participate. The age and gender distribution was similar in both the participants and the non-participants: the average age was of 67 years (±11.6) and 56.1% were men. The most common primary tumours sites in these patients were the lung (18.5%), followed by the pancreas (14.7%) and head or neck (14.0%). Participants and non-participants were similar (P-value=0.80) on perceived health rated on a scale of 0 to 10: 6.8 (±2.1) and 6.0 (±2.1), respectively.

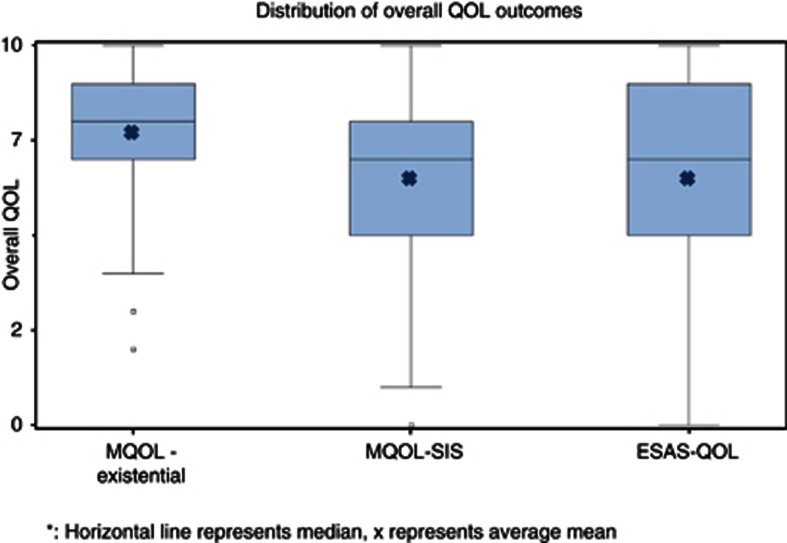

The distributions of the three outcomes of overall QOL are presented in Figure 3. MQOL-Existential, MQOL-SIS and ESAS-QOL (rescored) all ranged from 0–10, 10 indicating best quality of life and 0 the worst. Participants rated their QOL similarly with all measures of overall QOL. The medians were 7.9 for MQOL-Existential and 7.0 for MQOL-SIS and ESAS-QOL. The interquartile ranges spanned 2 units for MQOL-Existential, 3 for MQOL-SIS and 4 for ESAS-QOL. Of the three outcomes of overall QOL, MQOL-Existential had a smaller distribution, not unexpected with a multi-item index.

Figure 3.

Distribution of overall QOL outcomes.

Univariate associations

The screening of the associations between the 57 potential explanatory variables and each measure of overall QOL by simple linear regression led to the elimination of between 7 and 17 variables per outcome variable. Of the retained variables, 34 had statistically significant associations with all three outcomes of overall QOL, 7 with two outcomes and only 3 were associated with only one outcome of overall QOL.

The univariate correlation coefficients were consistent with expectations. The correlation coefficients between the contributor variables and the outcomes varied from 0.01 to 0.59.

Stepwise multiple linear regression analyses

Table 2 summarises the rankings in partial R2, from 1 (the most important) to 10 (the least important), of the first 10 variables identified by the three independent stepwise regressions, using the ranking for MQOL-Existential for the ordering of variables. Also presented are the effect sizes as measured by the t-test value.

Table 2. Relative ranking and effect sizes of items measuring symptoms, function and general health perception for QOL using adjusted R 2-stepwise regression.

| QOL outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MQOL-existential (total

R

2

=0.66)

|

MQOL-SIS (total

R

2

=0.69)

|

ESAS-QOL (total

R

2

=0.68)

|

|

|||||

| Partial R 2 rank | Effect size ( t -value) | Partial R 2 rank | Effect size ( t -value) | Partial R 2 rank | Effect size ( t -value) | Average R 2 ranks a | Average effect sizesa (t-value) | |

|

Contributor constructs

| ||||||||

| General health perception |

1 (R2=0.32) |

4.9 |

1, 9b

(R2=0.50) |

8.6, 3.5b |

|

|

3.0 |

5.5 |

| Psychological distress |

2 |

6.5 |

2 |

3.3 |

7 |

2.3 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

| Social support |

3 |

7.1 |

|

|

3 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

5.6 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | ||||||||

| Smell | 4 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 3.0 | ||||

| Lack of appetite | 5 | 2.8 | 3, 7, 10 b | 3.9,2.9, 2.0b | 10 | 2.5 | ||

| Taste | 9 | 3.6 | 6 | 2.1 | ||||

| Vomiting | 4 | 2.6 | ||||||

| Stomach pain | 8 | 2.0 | ||||||

| Interest in food |

|

|

|

|

9 |

2.2 |

|

|

| Fatigue |

6, 7b |

3.8, 4.3b |

4 |

3.2 |

2 |

5.2 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

| Social function |

8 |

4.0 |

|

|

|

|

8.0 |

4.0 |

| Pain |

|

|

6 |

2.3 |

5 |

2.2 |

5.5 |

2.3 |

| Physical function | 10 | 4.2 | 5, 8b | 3.5, 4.2b | 1 (R2=0.39) | 3.1 | 5.8 | 3.7 |

Average R2 rank: lower is first; Average effect sizes: higher is first.

By individual item contribution. Also represented is the Partial R2 of the 1st ranked item.

When overall QOL was represented by MQOL-Existential, the variable with the highest partial R2 was general health perception (GHP) from the RAND-36, followed by the psychological domain of the MQOL (rank 2) and social support domain (rank 3). When overall QOL was represented by MQOL-SIS, GHP (from MQOL) retained the first rank, followed by the psychological domain of the MQOL (rank 2), and an item of the Faact measuring appetite (rank 3).

When overall QOL was represented by ESAS-QOL, a subscale measuring physical function in the MFI held the first rank; an item measuring fatigue from the ESAS was ranked second, followed by the social support domain of the MQOL (rank 3).

The last two columns of Table 2 present the averages of the R2 rankings and of the effect sizes. Using R2, the most important constructs contributing to overall QOL was social support and GHP (both with an average R2 ranking of 3.0), followed by psychological distress, and relatively closely by fatigue. Using effect sizes, the same general order of the most important contributors remained. However, the effect sizes identified social function as much an important contributor. Both R2 and effect sizes ranked physical function and symptoms profile in the same order. The two methods of average ranking produced statistically similar hierarchies when compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P=0.58).

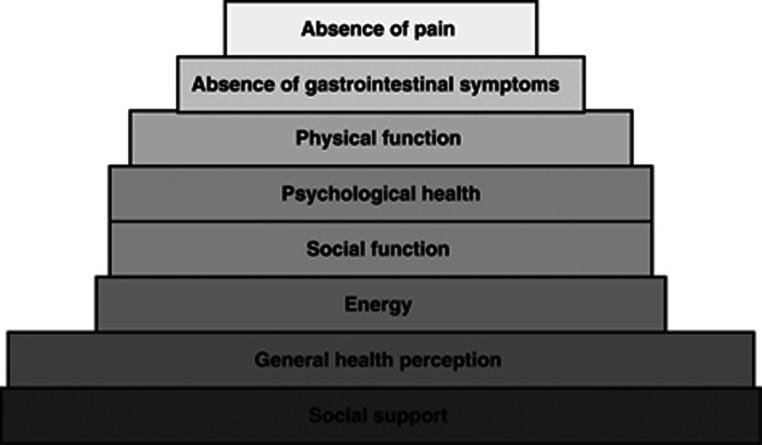

We represented the hierarchy of contributors of the overall QOL in people with advanced cancer as a pyramid analogous to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1948) (Figure 4). As the pyramid identified needs, some constructs were modified to convey a positive meaning (‘fatigue' was for instance modified to ‘energy').

Figure 4.

The hierarchy of contributors to QOL in people with advanced cancer.

Discussion

Using multiple stepwise linear regression models, a large number of potential contributors to overall QOL were reduced to a manageable and interpretable clinical picture. Similar and sometimes different contributors were identified according to how the latent construct of overall QOL was represented.

Apart from random error, differences in the importance rankings by outcome undoubtedly arise from differences in the QOL outcomes themselves. Two outcomes were single items (MQOL-SIS and ESAS-QOL) and one was a subscale with a total score derived from averaging scores on 6 items (MQOL-Existential).

In the MQOL-SIS, the patient is asked to contemplate all aspects of his or her life (physical, emotional, social, spiritual and financial) (Cohen et al, 1997) and provide a value between 0 and 10. MQOL-Existential includes concerns regarding death, freedom, isolation and the meaning of life, as existential concerns have been demonstrated to be of great importance to people with a life-threatening illness and is under-represented in many measures assessing QOL (O'Connor et al, 1990; Fryback, 1993).

In contrast, ESAS-QOL is 1 of 10 visual analogue scales (VAS) describing how a person would best describe their health in the last 24 h. The health states include QOL and a variety of physical symptoms, usually of negative connotation such as fatigue, nausea, depression or pain (Bruera et al, 1991). It is therefore possible that although patients are asked to rate their general QOL, the context in which the item is asked is likely to influence the rating. Our study found that the contributing variables to the ESAS-QOL single-item were almost inversely ordered in terms of importance with respect to MQOL-Existential and MQOL-SIS.

We translated the findings from combining the results from the different the regression analyses into a ‘pyramid of needs' mimicking Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1948) to emphasise that these are key areas of everyday life and function that people with threatened health need in order to continue to view life as worth living (World Health Organisation, 2001).

Social support was found to be the most important contributor to overall QOL meaning that, on average, people with advanced cancer who that reported being supported by their social surrounding also reported higher levels of overall QOL. By the term ‘social support', we refer mainly to the resources provided by other persons (Cohen and Syme, 1985). It has also been defined as the cognitive appraisal of being ‘reliably connected to significant others in a given social environment (Mathisen et al, 2007). Interestingly, it also fits with another identified contributor to overall QOL, social function. Social function can be defined as the actions and tasks required for basic and complex interactions with people in a contextually and socially appropriate manner (Cao et al, 2012). Therefore, the two concepts are closely related, as a socially functional individual will likely have a strong social support system in place that could be used as a coping mechanism and vice-versa.

Social support is becoming recognised as an important contributor of overall QOL in people with cancer. In a study on the prevalence and contributors to the unmet needs and their association with QOL, 296 men with advanced cancer were evaluated. Social support scores significantly predicted total overall QOL scores, to the same extent that psychological or physical symptoms did (Hwang et al, 2004). Recently, several studies have been recommending measuring social support as part of the assessment of people with cancer as they are key elements of their well-being (Gallagher and Vella-Brodrick, 2008; Hahn et al, 2010; McCabe and Cronin, 2011). The role of social support at end-of-life is recognised and is one of the key roles played by volunteers in hospice system (Pesut et al, 2012).

Other important contributors to overall QOL were fatigue, psychological distress, pain and physical function. This is consistent with the published literature. Pain, depression and fatigue are highly prevalent in cancer patients, and they often coexist. Laird et al (2011) recently identified that pain, depression and fatigue was an identifiable symptom cluster in a cohort of advanced cancer patients and is associated with reduced physical functioning. Similarly, a study on 1630 stage 3 and 4 Danish cancer patients identified the most prevalent symptoms contributing to a deterioration of QOL (Johnsen et al, 2009) as being fatigue (57% severe 22%) followed by reduced role function, insomnia and pain (Johnsen et al, 2009). The importance of the prevalence of these symptoms is such that in 2003, the National Institute of Health convened a State-of-the-Science Conference on pain, depression and fatigue symptom management in people with cancer in order to identify directions for future research (Patrick et al, 2003).

The self-reported overall QOL found in our study was strikingly similar to other studies with comparable populations. Lowe et al (2009) evaluated 50 adult advanced cancer patients with estimated life expectancies of 3 to 12 months from outpatient palliative care clinic and home care. Patients obtained a mean QOL score of 7.4±1.4 on the MQOL-Existential and 6.1±2.0 on ESAS-QOL (scale reversed from the original score of 3.9±2.0) (Lowe et al, 2009). Similarly, 38 patients with advanced cancer were evaluated using MQOL-Existential and obtained a mean score of 7.9±1.2 (Sherman et al, 2006). The same can be observed for reports of the MQOL-SIS: Jones et al (2010) obtained a mean MQOL-SIS score of 6.1±1.4 when assessing 211 cancer patients admitted to an acute palliative care unit in a comprehensive cancer center.

This study included only patients with advanced disease, so the results may not be generalise to patients at the early stages of the disease. Regression approaches identify only those variables that, in the presence of all others, make a unique and direct contribution to the outcome, here overall QOL. A limitation is that variables which impact indirectly through other variables are not identified; nevertheless this approach provides a minimum portfolio of variables, which would be a starting in developing a more complex model requiring structural equation modelling (SEM). Another limitation of this approach is that the latent construct of overall QOL had to be modelled as different variables; SEM would allow the different representations of overall QOL to contribute statistically to a latent variable.

We demonstrated a novel way of using multivariate linear regressions to make sense of a large amount of information to a more manageable and clinically interpretable picture. However, the variation in the contributors to QOL has relevant implications for the clinical management of patients with advanced cancer. Depending on the instrument used, the focus of the interventions by the various health professionals would be different. Also, in the research setting, the choice of the instrument will greatly influence the ‘measured' change in QOL secondary to the intervention(s) under study.

Social support is identified as the most important contributor to overall QOL in people with a recent diagnosis of advanced cancer. For health-care practitioners, this translates into assessing or asking patients recently diagnosed with cancer about their social networks and support and to arrange access for support when it is absent. The results also suggest paying particular attention to assessing and controlling physical function, fatigue, psychological distress, pain and gastrointestinal symptoms from the time of diagnosis. This would indicate that a team approach to measurement and care through the involvement of health-care professionals whose expertise lie in these domains (physical and occupational therapists, psychologists, social workers, nutritionists and palliative care physicians) would complement usual oncology care.

An interdisciplinary team approach, with a particular focus on physical function and fatigue, was found to be associated with improvement in overall QOL for patients with head and neck cancer (Eades et al, 2013). A recent clinical trial on the effect of early involvement of palliative care physicians and nurses in the care of patients with advanced lung cancer reported a significant improvement in overall QOL for the intervention group compared with patients receiving usual care (Temel et al, 2010). As the outcome for this study included items measuring physical function and fatigue, the effect may have been larger if the team had included health-care professionals with specialized expertise in those domains.

The involvement of health-care professionals with specific expertise in the management of cancer-related symptoms, psychological distress and loss of physical and social functions, supported by the integrated involvement of volunteers (Pesut et al, 2012), should be considered the new standard of care for patients with advanced cancer with decreased overall QOL. This is particularly important as fewer than 10% of oncology patients have been reported to receive psychosocial therapy (Lee et al, 2005b).

Modern health-care emphasises patient-centered care defined by a focus on outcomes that people notice and care about including, not only survival, but also function, symptoms and modifiable aspects of QOL (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Insitute, 2013). Thus, the measurement and optimisation of the contributors to QOL, such as those identified in this study, would be necessary components of a patient-centered oncology program.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Terry Fox Research Institute. B Gagnon is a recipient of ‘Chercheur-clinicien Boursier' award from Fonds de recherche Santé Québec. We also thank Dr Neil MacDonald, Dr Lorenzo Ferri, Dr Peter Metrakos, Dr Linda O'Faria, Dr Catalin Mihalcioiu, Dr Victor Cohen, Dr Carmela Pepe, Dr David Small, Dr Chaudhury and Dr Prosanto, for their input or help in recruiting participants. We finally with to thank the participants and their families who gave their valuable time to participate in the study.

Appendix A

Reference List

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O'Brien WL, Bassett DR, Jr, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS (2000) Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32 (9 Suppl): S498–S504

Benton AL, Hamsher KS, Varney NR, Spreen O (1983) Serial Digit Learning. In: Neuropsychological Assessment: A Clinical Manual Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA.

Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M (2000) Validation of the edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer 88 (9): 2164–2171

Cohen SR, Boston P, Mount BM, Porterfield P (2001) Changes in quality of life following admission to palliative care units. Palliat Med 15 (5): 363–371

Cohen SR, Hassan SA, Lapointe BJ, Mount BM (1996a) Quality of life in HIV disease as measured by the McGill quality of life questionnaire. AIDS 10 (12): 1421–1427

Cohen SR, Mount BM (2000) Living with cancer: ‘good' days and ‘bad' days--what produces them? Can the McGill quality of life questionnaire distinguish between them? Cancer 89 (8): 1854–1865

Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, Tong K (1997) Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliative Med 11 (1): 3–20

Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F (1995) The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med 9 (3): 207–219

Cohen SR, Mount BM, Tomas JJ, Mount LF (1996b) Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer 77 (3): 576–586

de Haan R, Aaronson N, Limburg M, Hewer RL, van Crevel H (1993) Measuring quality of life in stroke. Stroke 24 (2): 320–327

Fillion L, Gelinas C, Simard S, Savard J, Gagnon P (2003) Validation evidence for the French Canadian adaptation of the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory as a measure of cancer-related fatigue. Cancer Nurs 26 (2): 143–154

Fransen M, Crosbie J, Edmonds J (1997) Reliability of gait measurements in people with osteoarthritis of the knee. PHYS Ther 77 (9): 944–953

Goodyear MDE, Fraumeni MA (1996) Incorporation Quality of Life Assessment into Clinical Cancer Trials. In Spilker B (ed) pp Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Care, 1003–1013. Lippincott-Raven Publishers: Pennsylvania, PA, USA

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM (1993) The RAND-36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ 2 (3): 217–227

Holden MK, Gill KM, Magliozzi MR (1986) Gait Assessment for Neurologically Impaired Patients: Standards for Outcome Assessment. Phys Ther 66 (10): 1530–1539

Meek PM, Nail LM, Barsevick A, Schwartz AL, Stephen S, Whitmer K, Beck SL, Jones LS, Walker BL (2000) Psychometric testing of fatigue instruments for use with cancer patients. Nursing Res 49 (4): 181–190

Nakamura R, Handa T, Watanabe S, Morohashi I (1988) Walking cycle after stroke. Tohoku J Exp Med 154 (3): 241–244

Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C (2008) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: a 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991–2006) Palliat Med 22 (2): 111–122

Norum J (1996) Quality of life (QoL) measurement in economical analysis in cancer: A comparison of the EuroQol questionnaire, a simple QoL-scale and the global QoL measure of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Oncol Rep 3 787–791

O'Carroll RE, Conway S, Ryman A, Prentice N (1997) Performance on the delayed word recall test (DWR) fails to differentiate clearly between depression and Alzheimer's disease in the elderly. Psychol Med 27 (4): 967–971

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S (1991) The timed up and go—a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39 (2): 142–148

Poissant L, Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Clarke AE (2003) The development and preliminary validation of a preference-based stroke index (PBSI) Health Qual Life Outcomes 1 43, doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-43 [doi]1477-7525-1-43 [pii]

Ribaudo JM, Cella D, Hahn EA, Lloyd SR, Tchekmedyian NS, Von RJ, Leslie WT (2000) Re-validation and shortening of the functional assessment of anorexia/cachexia therapy (FAACT) questionnaire. Qual Life Res 9 (10): 1137–1146

Richardson LA, Jones GW (2009) A review of the reliability and validity of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Curr Oncol 16 (1): 55

Schneider RA (1998) Reliability and validity of the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI-20) and the Rhoten fatigue scale among rural cancer outpatients. Cancer Nursing 21 (5): 370-373

Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, de Haes JC (1995) The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 39 (3): 315–325

Solway S, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, Thomas S (2001) A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 119 (1): 256–270

Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL (2001a) CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exercise 33 (7): 1126–1141

Stewart AL, Verboncoeur CJ, McLellan BY, Gillis DE, Rush S, Mills KM, King AC, Ritter P, Brown BW, Jr., Bortz WM (2001b) Physical activity outcomes of CHAMPS II: a physical activity promotion program for older adults. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 56 (8): M465–M470

Venturini, A, Wilford, C, Finch, L, Spetsieris, P, and Rubinoff, S 1995. The Timed Up and Go: Reliability and Validity in an Acute Neurological Population. World Congress of Physiotherapy (Abstract).

Wood-Dauphinee, S, Mayo, N, Jung, H, and Shen, N. Does the SF-36 reflect changes in the health of people with stroke? 5th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research: 15–17 November 1998, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Abstract]. Quality Life Res. 7[7], 561–682. 1998.

Appendix B

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

- Bennett SJ, Perkins SM, Lane KA, Deer M, Brater DC, Murray MD. Social support and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure patients. Qual Life Res. 2001;10 (8:671–682. doi: 10.1023/a:1013815825500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7 (2:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2010Transforming Care for Canadians with Chronic Health Conditions: Put People First, Expect the Best, Manage for Results, Ottawa.

- Cao MD, Sitter B, Bathen TF, Bofin A, Lonning PE, Lundgren S, Gribbestad IS. Predicting long-term survival and treatment response in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy by MR metabolic profiling. NMR Biomed. 2012;25 (2:369–378. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrischilles EA, Rubenstein LM, Voelker MD, Wallace RB, Rodnitzky RL. Linking clinical variables to health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8 (3:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Syme SL.1985Issues in the study and application of social supportIn Cohen S, Syme SL (eds)Social Support and Health 3–41.Academic Press Inc.: Orlando, FL, USA [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, Tong K. Validity of the McGill quality of life questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliative Med. 1997;11 (1:3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosby C, Holzemer WL, Henry SB, Portillo CJ. Hematological complications and quality of life in hospitalized AIDS patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14 (5:269–279. doi: 10.1089/108729100317731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham WE, Crystal S, Bozzette S, Hays RD. The association of health-related quality of life with survival among persons with HIV infection in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20 (1:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eades M, Murphy J, Carney S, Amdouni S, Lemoignan J, Jelowicki M, Nadler M, Chasen M, Gagnon B. Effect of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation program on quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer: review of clinical experience. Head Neck. 2013;35 (3:343–349. doi: 10.1002/hed.22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryback PB. Health for people with a terminal diagnosis. Nurs Sci Q. 1993;6 (3:147–149. doi: 10.1177/089431849300600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher EN, Vella-Brodrick DA. Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Person Individual Differences. 2008;44 (7:1551–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EA, Devellis RF, Bode RK, Garcia SF, Castel LD, Eisen SV, Bosworth HB, Heinemann AW, Rothrock N, Cella D. Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): item bank development and testing. Qual Life Res. 2010;19 (7:1035–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9654-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Cunningham WE, Sherbourne CD, Wilson IB, Wu AW, Cleary PD, McCaffrey DF, Fleishman JA, Crystal S, Collins R, Eggan F, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA. Health-related quality of life in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Am J Med. 2000;108 (9:714–722. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo S, Moser DK, Riegel B, Hall LA, Christman N.2005Testing a published model of health-related quality of life in heart failure J Card Fail 11(5372–379.[pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SS, Chang VT, Cogswell J, Alejandro Y, Osenenko P, Morales E, Srinivas S, Kasimis B. Study of unmet needs in symptomatic veterans with advanced cancer: incidence, independent predictors and unmet needs outcome model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28 (5:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Groenvold M. Symptoms and problems in a nationally representative sample of advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2009;23 (6:491–501. doi: 10.1177/0269216309105400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Cohen SR, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Quality of life and symptom burden in cancer patients admitted to an acute palliative care unit. J Palliat Care. 2010;26 (2:94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird BJ, Scott AC, Colvin LA, McKeon AL, Murray GD, Fearon KC, Fallon MT. Pain, depression, and fatigue as a symptom cluster in advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42 (1:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.10.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DT, Yu DS, Woo J, Thompson DR. Health-related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005a;7 (3:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Loberiza FR, Antin JH, Kirkpatrick T, Prokop L, Alyea EP, Cutler C, Ho VT, Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Fisher DC, Logan B, Soiffer RJ. Routine screening for psychosocial distress following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005b;35 (1:77–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang MH, Fossel AH, Larson MG. Comparisons of five health status instruments for orthopedic evaluation. Med Care. 1990;28 (7:632–642. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SS, Watanabe SM, Baracos VE, Courneya KS. Associations between physical activity and quality of life in cancer patients receiving palliative care: a pilot survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38 (5:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrett LD, De P, Airia P, Dryer D. Cancer in Canada in 2008. CMAJ. 2008;179 (11:1163–1170. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Higher and lower needs. J Psychol. 1948;25:433–436. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1948.9917386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen L, Andersen MH, Veenstra M, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Fosse E. Quality of life can both influence and be an outcome of general health perceptions after heart surgery. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe C, Cronin P. Issues for researchers to consider when using health-related quality of life outcomes in cancer research. Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20 (5:563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molzahn AE, Northcott HC, Hayduk L. Quality of life of patients with end stage renal disease: a structural equation model. Qual Life Res. 1996;5 (4:426–432. doi: 10.1007/BF00449917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor AP, Wicker CA, Germino BB. Understanding the cancer patient's search for meaning. Cancer Nurs. 1990;13 (3:167–175. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982. pp. 649–655. [PubMed]

- Osoba D. Translating the science of patient-reported outcomes assessment into clinical practice. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007. pp. 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pace NL. Independent predictors from stepwise logistic regression may be nothing more than publishable P values. Anesth Analg. 2008;107 (6:1775–1778. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818c1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Insitute 2013 ) http://www.pcori.org/about/mission-and-vision/ .

- Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, Harris JJ, Hendricks CB, Levin B, Link MP, Lustig C, McLaughlin J, Ried LD, Turrisi AT, III, Unutzer J, Vernon SW. National institutes of health state-of-the-science conference statement: symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue, 15–17 July, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95 (15:1110–1117. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesut B, Hooper B, Lehbauer S, Dalhuisen M.2012Promoting volunteer capacity in hospice palliative care: a narrative review Am J Hospice Palliative Mede-pub ahead of print 31 December 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sherman DW, Ye XY, McSherry C, Parkas V, Calabrese M, Gatto M. Quality of life of patients with advanced cancer and acquired immune deficiency syndrome and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2006;9 (4:948–963. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa KH, Chen FF. A theoretical approach to measuring quality of life. J Nurs Meas. 2002;10 (1:47–58. doi: 10.1891/jnum.10.1.47.52545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa KH, Holzemer WL, Henry SB, Slaughter R. Dimensions of health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV disease. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29 (1:178–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa KH, Kwok OM. Putting Wilson and Cleary to the test: analysis of a HRQOL conceptual model using structural equation modeling. Qual Life Res. 2006;15 (4:725–737. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-3975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa KH, Williamson A. Symptom status and health-related quality of life: clinical relevance. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42 (6:571–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straits-Troster K, Fields JA, Wilkinson SB, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Koller WC, Troster AI. Health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease after pallidotomy and deep brain stimulation. Brain Cogn. 2000;42 (3:399–416. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363 (8:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettergren L, Bjorkholm M, Axdorph U, Langius-Eklof A. Determinants of health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Qual Life Res. 2004;13 (8:1369–1379. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040790.43372.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273 (1:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Clinical predictors of functioning in persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Care. 1996;34 (6:610–623. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Clinical predictors of declines in physical functioning in persons with AIDS: results of a longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;16 (5:343–349. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199712150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: ICF. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 2001. [Google Scholar]