Abstract

The theory of self-authorship describes the developmental process students undergo in the transition away from dependence on authority figures for learning and identity. Self-authored individuals are also capable of self-directed learning, critical thinking, complex problem-solving, mature decision-making, and the development of collaborative relationships with diverse others. According to this theory, an individual’s transformation to self-authorship is not instantaneous but occurs over time, and that college experiences can be designed to promote development of self-authorship. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) encourages the use of innovative instructional methods that “enable students to transition from dependent to active, self-directed, lifelong learners.”1 The developmental theory of self-authorship is a theory of cognitive and affective growth that could help pharmacy educators better examine and define the role of academia in the holistic professional development of pharmacy students. The Learning Partnerships Model, which is based on the theory of self-authorship, describes a student-centered approach to pharmacy education that promotes self-authorship.

Keywords: self-authorship, learning partnerships model, critical thinking, professional identity

INTRODUCTION TO SELF-AUTHORSHIP

The 2011 revisions of the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards and Guidelines “focus on the development of students’ professional knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values, as well as sound and reasoned judgment and the highest level of ethical behavior.” The standard revisions place additional emphasis on the “importance of the development of the student as a professional and lifelong learner.”1 ACPE has a holistic view of the professional education of pharmacy students in that it must promote both cognitive (knowledge and skills) and affective (attitudes and values) growth. The theory of self-authorship, currently unexplored in pharmacy literature, could help pharmacy educators better investigate and define the role of academia in the holistic professional development of pharmacy students.

Much of ACPE’s description of a graduating pharmacy student or new practitioner can be explained by the developmental theory of self-authorship. The theory of self-authorship is essentially a theory of integrated intellectual and personal maturity, defined as “the ability to collect, interpret, and analyze information and reflect on one’s own beliefs in order to form judgments.”2 This definition of self-authorship is reminiscent of critical thinking, a cognitive exercise that questions assumptions and relies on observation and analytical reasoning. Thus, it is a theory of cognitive or intellectual maturity. Notably, the theory of self-authorship additionally addresses the affective domain of development — students’ attitudes, values, and motivations — their personal maturity.2,3 The affective domain of self-authorship allows students to develop their “own beliefs,” against which they judge the validity of new knowledge per the definition of self-authorship described above. Those internal beliefs also serve as the backdrop to new relationships with other individuals, who often have conflicting beliefs.

College education (and consequently pharmacy college or school) can be seen as a journey to self-authorship wherein, as students are challenged both personally and intellectually, they acquire and analyze knowledge, develop a personal identity, and learn to form complex, diverse relationships.4 The kinds of educational experiences that provoke a transformation to self-authorship in college students are described in the pedagogical Learning Partnerships Model5 as blending guidance with responsibility for learning, which creates a student-centered learning environment that empowers the learner. Beyond merely conveying knowledge of a subject, pharmacy educators can use the model to create challenging and provocative experiences that catalyze the development of self-authorship in pharmacy students, leading to their personal (affective) and intellectual (cognitive) development and preparing them for the personal and professional challenges of adult life.

THE TRANSFORMATION TO SELF-AUTHORSHIP

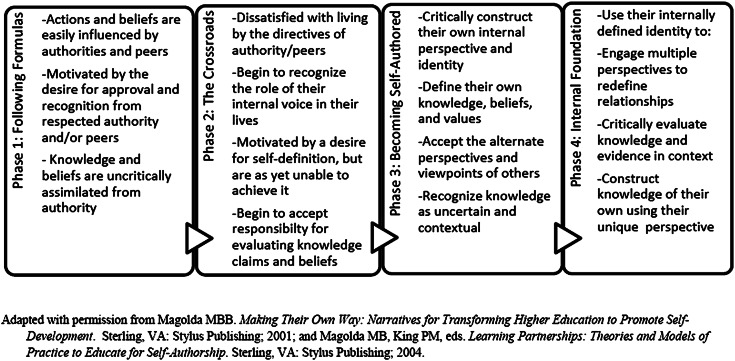

Self-authorship theory states that an individual’s transformation to self-authorship is not instantaneous but occurs over time in 4 sequential phases: (1) Following Formulas, (2) the Crossroads, (3) Becoming the Author of One’s Life, and (4) Internal Foundations (Figure 1).4 In the initial phase, Following Formulas, adolescents rely on external opinions for their values and beliefs. Their identity or “self” is externally defined and easily influenced by others, often their peers. They adopt externally defined “formulas for success” to not only guide their actions but also define their successes. Students often enter college in this phase, and have followed the advice of others (a formula for success) to get there. Because students in this phase lack the ability to critically evaluate new knowledge from other perspectives, they trust in authority figures to provide them with complete and accurate information. They view knowledge as certain and immutable and are not inspired to examine or question it. They rely on guidance from respected authority for affirmation, approval, and success.4

Figure 1.

Progression Through the 4 Phases of Self-Authorship Development. Students may be in different phases of development for each of the 3 domains of self-authorship2-4,6: knowledge, self, and others. Progression through the phases begins at different times and occurs at different rates for individuals. Transition through the phases is generally stimulated by provocative experiences that generate disequilibrium and force students to reevaluate their conceptions of themselves and how they know.

Students reach a developmental crossroads when they become dissatisfied with living by others’ definitions and knowledge and begin to question authority. When they reach The Crossroads, students have gained a greater awareness of their own independence and, feeling unsatisfied with living by others’ expectations, seek self-definition and envision directing their own lives. In the process of defining themselves, they reach the third phase in the transformation to self-authorship: becoming the author of one’s own life. Students begin to choose what they believe and value and develop a personal perspective they can defend against conflicting viewpoints. They shift away from accepting knowledge imparted by authority and start to take responsibility for evaluating that knowledge, accepting its biased, uncertain, and contextual nature.4

As students apply their newly self-defined identity and perspective to external events, they reach the final phase of self-authorship: internal foundations. In this phase, they use their internal perspective to evaluate and appreciate other diverse perspectives and use their beliefs and values to guide their actions and decision-making. Rather than assimilating knowledge from authority, self-authored students accept that knowledge is socially invented and, therefore, use their individual perspective to participate in active knowledge construction, often in collaboration with peers and mentors.4

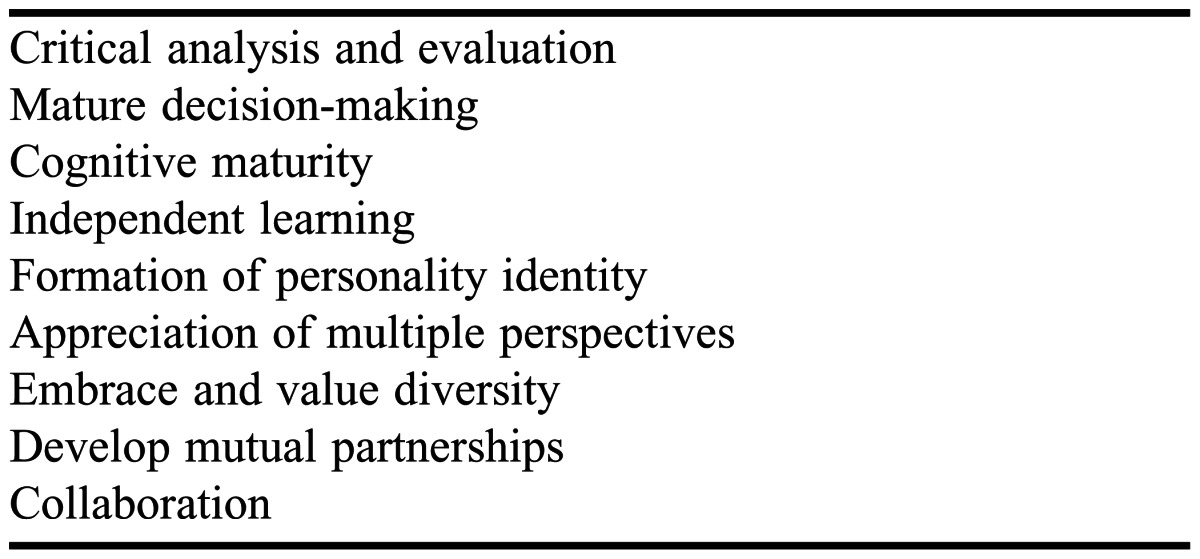

Each of these 4 phases marks a distinct point in a student’s transition away from reliance on authority and toward internal definition, becoming the author of his/her own life. The transition to self-authorship requires students to accept responsibility for defining their own beliefs, values, identity, and meaning; this internal authority then becomes their perspective on learning and relationships. A self-authored person is consciously building his/her identity as an individual and a professional by critically self-evaluating and reflecting on important life experiences. Self-authored individuals are also capable of critically evaluating knowledge, enabling critical thinking, complex problem-solving, and mature decision-making. A willingness to accept and appreciate multiple perspectives brought about through open-minded rationality and confidence in their internal identity allows students to develop complex relationships with diverse individuals (Table 1).2-4,6

Table 1.

Characteristics of Self-Authored Individuals2-4,6

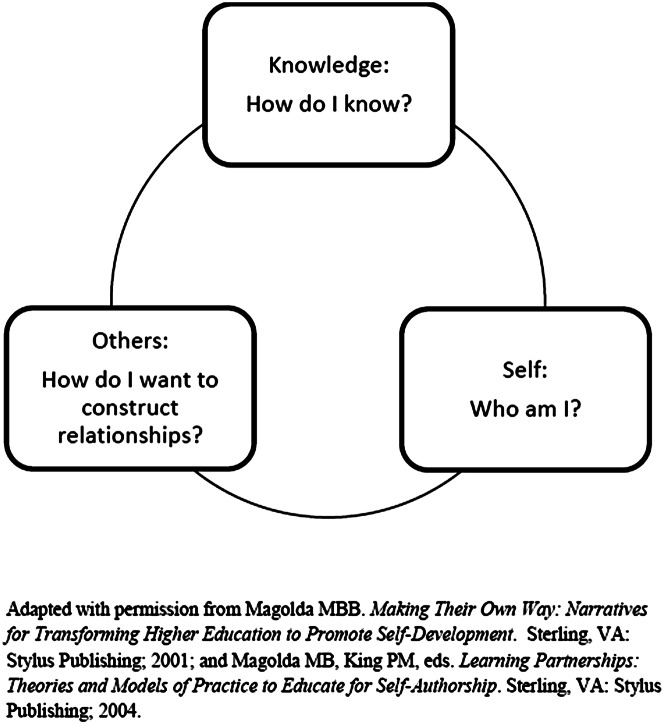

Thus, self-authorship affects multiple dimensions of thinking, including cognitive thought, which is the typical focus of academic instruction, as well as intrapersonal identity and interpersonal relationships, which are more affective domains.6 This thematic triad of knowledge, self, and others, which persists throughout self-authorship literature, allows a student to answer the questions “How do I know?” “Who am I?” and “How do I want to construct relationships with others?” (Figure 2)4 Self-authorship is more than a skill that can be taught; it requires a transformation in a students’ understanding of the contextual nature of knowledge, a confidence in themselves and their unique identity, and an appreciation of relative perspective.2-6

Figure 2.

Three Domains of Self-Authorship. The theory of self-authorship2-4 incorporates both cognitive and affective domains of student development (ie, knowledge [cognitive], self [affective] and others [affective]), each of which influences the other 2. For example, the development of a personal identity and perspective allows the self-authored student to use relative perspective to critically evaluate knowledge and relationships from alternate perspectives

DEVELOPING SELF-AUTHORSHIP IN COLLEGE

In 1986, Marcia Baxter Magolda initiated a qualitative, longitudinal study of 101 entering college freshman designed to evaluate their learning and intellectual development throughout college.3 Magolda continued to follow a smaller, longitudinal cohort of 39 participants beyond college and into their graduate work and professional careers, evaluating their progression to self-authorship through yearly telephone interviews. She documented students’ assumptions of the nature of knowledge, the role of the student in the learning process, and personal experiences that affected their assumptions of the certainty of knowledge.4 The students’ achievement of self-authorship was measured by assessing what Magolda referred to as their “ways of knowing.”3,4

Absolute knowing, according to Magolda, is the assumption that knowledge is certain and known to authorities. Absolute knowing was most prevalent type of knowing among students in their first 2 years of college.4 Transitional knowing, in which knowledge is somewhat certain and somewhat uncertain, was the predominant way of knowing among students in their last 3 years of a traditional 4-year undergraduate degree. Few students used independent knowing, which assumes knowledge is uncertain and influenced by individual bias, though independent knowing came to be much more common in the study cohort’s fifth-year interviews, shortly after graduation. The goal of self-authorship is contextual knowing, wherein self-authored individuals view knowledge in relative context, evaluate the validity of knowledge claims, and use informed judgment to determine what to believe.4

Magolda determined that only 2 of her original 101 students had achieved self-authorship by 1 year postgraduation. Many of the 39 students she followed well beyond college and into their late 20s and 30s did not began to exhibit signs of self-authorship until several years beyond college. Magolda argues that her research participants did not generally achieve self-authorship in undergraduate coursework because colleges too frequently supplied students with formulas for success rather than providing experiences that promote self-authorship.3,4,6

Her research noted that major progression through the phases of self-authorship was initiated by provocative experiences and situations that disrupted students’ equilibrium, challenged their dependence on knowledge from authority, and compelled them to consider and construct new conceptions of themselves and their knowledge. It was only by challenging students’ traditional ways of knowing that they could progress.4 Students had to move away from thinking there is always a single right answer that is known to the authority (ie, absolute knowing) and begin to see that knowledge requires analysis of relevant evidence in context and perspective (ie, contextual knowing). To progress, students had to either make decisions for which there were no formulas for success, or realize they were unhappy with following formulas outlined by others and commit to defining their own values, beliefs, and identities.4 Though study at the college level is intended to promote intellectual growth and development of knowledge, traditional study based on a predefined formula for success outlined by an authority may not be provocative enough to incite progression into the next phase of self-authorship.3,4

These provocative experiences are not necessarily part of the college curriculum; race, faith, gender, sexual orientation, or social class can all expose students to confrontational experiences that promote progression to later phases of self-authorship prior to and outside of college.7 Jane Pizzolato researched the development of self-authorship in 35 “high-risk” college students, whose academic backgrounds, prior performance, and personal characteristics placed them at high risk of academic failure or college withdrawal.8 Her research suggests that high-risk students achieve self-authorship earlier than low-risk students because they may be forced to overcome personal obstacles in the process of gaining admission to college. In communities where higher education is uncommon, students strongly desiring to attend college may have to act in ways that make them stand out from their peers, forcing them to develop self-authored ways (independence from authority and external influence) in their quest for college admission.7,8

Since Magolda’s initial investigation in 1998, self-authorship has emerged as a promising theory of college student development, supported by research in numerous other populations. A major limitation of the initial research was the inclusion of exclusively upper-middle-class Caucasian research subjects from Miami University, Ohio. Additional research has expanded the investigation into minority groups (eg, Latino students,9 lesbian students10) and alternate forms of higher education (eg, military academy11). These small, qualitative studies all corroborate Magolda’s findings: that provocative experiences in college promote self-authorship by forcing individuals to look inward for self-definition, rather than depending on others to define their knowledge, beliefs and values.

Privileged students similar to those in Magolda’s original cohort may not experience provocative situations related to their personal characteristics as many minority students do.4 Without exposure to situations that challenge them to develop an awareness of their own internal foundations, those privileged students may not as readily develop self-authorship skills that grant them independence from authority.4 If higher education’s goal is to develop self-authorship during college to prepare students for adult life, some students may require curricular learning experiences that challenge them to develop internal definition.

THE LEARNING PARTNERSHIPS MODEL

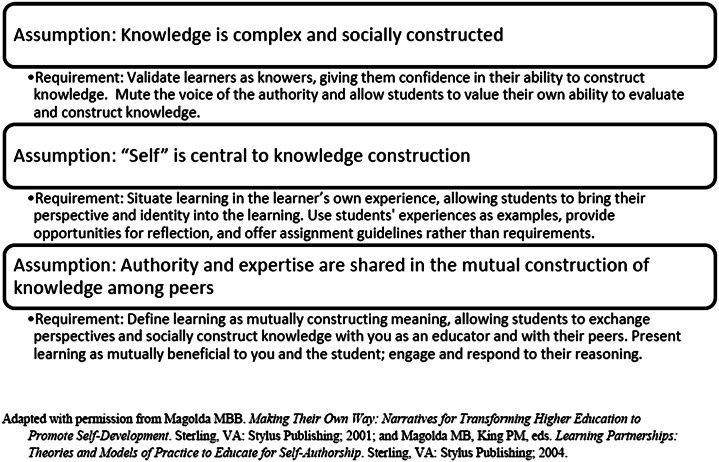

The provocative educational experiences that promote self-authorship are described in Magolda’s Learning Partnerships Model. The model is founded on 3 core assumptions: (1) knowledge is complex and socially constructed, (2) “self” is central to knowledge construction, and (3) authority and expertise are shared in the mutual construction of knowledge among peers. Under these assumptions, educational settings that promote self-authorship must: (1) validate learners as knowers, giving them confidence in their ability to construct knowledge; (2) situate learning in the learner’s own experience, allowing students to bring their perspective and identity into the learning; and (3) define learning as mutually constructing meaning, allowing students to exchange perspectives and socially construct knowledge (Figure 3).5

Figure 3.

The Learning Partnerships Model describes the pedagogy of self-authorship through assumptions about the three domains of self-authorship: knowledge, self, and others. Learning experiences that promote the development of self-authorship require educators to balance challenge and support, allowing students to explore their own voice and role in the social construction of knowledge. Engaging students in mutual learning supports their development and confidence of self.

The model portrays knowledge as the “complex result of experts determining what to believe” based on their collaborative perceptions of the evidence.5 By presenting knowledge as constructed, rather than passed down from authority, educators enable or empower learners to develop their own perspectives and engage in the mutual construction of knowledge with others. The 3 assumptions of the model match the 3 thematic domains of self-authorship: knowledge, identity, and relationships.2,5 This triad serves as the foundation for the entire self-authorship concept: students must believe in their own capacity to create contextual knowledge in cooperation with others. This concept leads back to Magolda’s original definition of self-authorship: “the ability to collect, interpret, and analyze information and reflect on one’s own beliefs in order to form judgments.”2

Some of the students in Magolda’s longitudinal research cohort entered graduate school following undergraduate education.4,12 During interviews with those students, Magolda noted that graduate schools tended to more actively promote self-authorship by, as suggested in the model, respecting students’ thinking, engaging students in exploring multiple perspectives, and conveying that students must construct their own perspectives by using the evidence of their discipline.12

Pharmacy college and school graduates are also expected to develop self-authorship during their education, as evidenced by ACPE’s goals of self-directed learning, development of a professional identity, and engagement in tolerant relationships that cross cultural boundaries.1 Though some aspects of modern pharmacy curricula use the pedagogy described in the model, a better understanding of self-authorship and use of the model in pharmacy education could help pharmacy educators better examine and define the role of academia in the holistic professional development of pharmacy students.

SELF-AUTHORSHIP IN PHARMACY EDUCATION

Experiential education, a necessary component of the pharmacy curriculum, fulfills many aspects of the Learning Partnerships Model by actively engaging students in discovering and evaluating new knowledge, allowing them to make informed recommendations regarding patient care, and encouraging their consideration of ethics in practice. During introductory and advanced pharmacy practice experiences, educators progressively relinquish authority over students’ learning experiences, encouraging questions from and sharing the role of the “drug information expert” with students. These experiences promote the development of skills and attitudes associated with self-authorship, including critical thinking, independent learning, and professional collaboration. Additionally, students develop their professional identity, against which they can consider the perspectives of others, allowing them to embrace and value diversity and build mature relationships with colleagues and patients.

The pedagogy of self-authorship, described in the model, balances challenge with support, and combines cognitive and affective development, providing a holistic approach to pharmacy education. Using this framework, pharmacy educators could develop or refine learning experiences to meet the criteria of the model and promote self-authorship.

According to the model, learning experiences that promote self-authorship must validate learners as knowers, giving them confidence in their ability to construct knowledge.5 Pharmacy educators often include students in their scholarly work. As they participate in research and scholarship, students explore the process of critical inquiry and build confidence in their ability to generate new knowledge. Service-learning, health fairs, and other public speaking or patient counseling experiences place students in the role of the expert or educator, which may also serve to build their confidence in their ability to learn.

Additionally, the LPM requires learning experiences to situate learning in the learner’s own experience, allowing students to bring their perspective and identity into the learning.5 Experiential training engages students in real-life situations, and reflection on those experiences may help students develop insights into how their experiences shape their perspective and identity, thus promoting self-authorship. Finally, the LPM defines learning as mutually constructing meaning, allowing students to work collaboratively to exchange perspectives and socially construct knowledge with their peers.5 Many colleges and schools of pharmacy have explored team-based learning and other group-learning strategies that allow students to direct their own learning experiences.

ACPE encourages the use of innovative instructional methods that “enable students to transition from dependent to active, self-directed, lifelong learners.”1 The theory of self-authorship adds a foundational understanding of the developmental process students undergo in the transition away from absolute knowing and dependence on knowledge passed from authority figures. The model, based on the theory of self-authorship, describes a student-centered approach to pharmacy education that promotes the development of self-authorship.

Self-authored students are capable of active knowledge construction, mature adult decision-making, interdependent relationships with others, and effective citizenship.2,7 By using the theory of self-authorship and the pedagogy of the LPM, pharmacy educators may be able to accelerate their achievement of ACPE’s broad educational goals of contextual knowledge, professional identity, and collaborative relationships.1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Dr. Elizabeth Yost Hammer of Xavier University of Louisiana, who introduced me to this topic and guided the development of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed August 17, 2012.

- 2.Magolda MBB. Three elements of self-authorship. J Coll Stud Dev. 2008;49(4):269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magolda MBB. Developing self-authorship in young adult life. J Coll Stud Dev. 1998;39(2):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magolda MBB. Making Their Own Way: Narratives for Transforming Higher Education to Promote Self-Development. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magolda MB, King PM, editors. Learning Partnerships: Theories and Models of Practice to Educate for Self-Authorship. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.King PM, Magolda MBB. A developmental model of intercultural maturity. J Coll Stud Dev. 2005;46(6):571–592. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meszaros PS, editor. Self-Authorship: Advancing Student’s Intellectual Growth: New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 109. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pizzolate JE. Developing self-authorship: exploring the experiences of high-risk college students. J Coll Stud Dev. 2003;44(6):797–812. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abes ES, Jones SR. Meaning-making capacity and the dynamics of lesbian college students’ multiple dimensions of identity. J Coll Stud Dev. 2004;45(6):612–632. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis P, Forsythe GB, Sweeney P, Bartone PT, Bullis C. Identity development during the college years: Finding from the West Point longitudinal study. J Coll Stud Dev. 2005;46(4):357–373. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres V, Magolda MBB. Reconstructing Latino identity: the influence of cognitive development on the ethnic identity process of Latino students. J Coll Stud Dev. 2004;45(3):333–347. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magolda MBB. Developing self-authorship in graduate school. New Dir High Educ. 1998;101(Spring):41–54. [Google Scholar]