Abstract

Objectives. To identify and assess changes made to the Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate program over 10 years to adapt to the growing number and changing needs of pharmacy educators in the next generation.

Design. In 2011, all resident program participants and directors were sent an electronic survey instrument designed to assess the perceived value of each program component.

Assessment. Since 2003, the number of program participants has tripled, and the program has expanded to include additional core requirements and continuing education. Participants generally agreed that the speakers, seminar topics, seminar video recordings, and seminar offerings during the fall semester were program strengths. The program redesign included availability of online registration; a 2-day conference format; retention of those seminars perceived to be most important, according to survey results; implementation of a registration fee; electronic teaching portfolio submission; and establishment of teaching mentors.

Conclusion. With the growing number of residents and residency programs, pharmacy teaching certificate programs must accommodate more participants while continuing to provide quality instruction, faculty mentorship, and opportunities for classroom presentations and student precepting. The Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate program has successfully evolved over the last 10 years to meet these challenges by implementing successful programmatic changes in response to residency program director and past program participant feedback.

Keywords: teaching certificate program, residency training

INTRODUCTION

The incorporation of teaching experiences within pharmacy residency programs has increased significantly in recent years. In 1999, the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy reported the first teaching program specifically designed for pharmacy residents: the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Certificate Program.1,2 Romanelli and colleagues recognized that the ability to teach, whether in the classroom or the clinical setting, is an expectation of all pharmacy residents.1 The skills required to become an effective teacher were not always taught or evaluated, possibly because of an emphasis on patient-care−related responsibilities.3 Since that time, teaching programs have been developed throughout the country to provide organized instruction for residents seeking competence in either classroom teaching or clinical precepting.4

Although there is no standardization of components or requirements offered in a teaching certificate program, many programs provide formal instruction in several components of teaching, including preparing classroom lectures and presentations, facilitating small-groups, precepting students, writing examination questions, and developing a teaching philosophy.4 Residents are also required to complete varied teaching experiences, such as formal presentations or lectures and facilitation of group discussions, throughout the residency year using skills acquired in the teaching certificate program. McNatty and colleagues determined that residents who had served as primary preceptors for practice-experience students, lectured to students, or participated in problem-based/small-group learning exercises were more likely to accept a faculty position.5 With the increase in availability of clinical pharmacy faculty positions affiliated with newer pharmacy colleges and schools, residents seeking a clinical pharmacy position may find themselves considering an academic job based on the current job market trends. Participation in a teaching certificate program provides residents with formal instruction and skills that can help prepare them for a faculty position.

Although not all pharmacy residents who complete a teaching certificate program will pursue a job in academia, the benefits gained from participating in such a program enable residents to share knowledge more effectively and efficiently with a wide range of audiences inside and outside the classroom.4 In a survey conducted to determine the perceived value of such programs 1 year after completion, 55% of respondents reported they often used the skills and knowledge obtained from their teaching certificate program in their current position. Less than 8% of these survey respondents reported being in an academic position, demonstrating that these teaching skills are being used not only by pharmacy faculty members but by clinical practitioners as well.6

As residency programs have expanded, so have the number of participants in teaching certificate programs.6,7 With this increase, it can be challenging to coordinate teaching seminars that fit the schedule of each participant. Given residents’ significant patient care responsibilities, it can also be difficult for them to justify attending multiple teaching sessions throughout the year. Additionally, clinically focused preceptors who may not consider teaching a priority of residency training may not support participation when multiple sessions are required.

The Indiana Pharmacy Teaching Certificate Program was developed in the fall of 2002 and implemented in the spring of 2003. After 10 years of successful program implementation, by 2012 the program coordinators were faced with many new challenges, including budget constraints, technology limitations, scheduling conflicts, and new generational learning styles. The purpose of this study was to identify and assess changes made to the Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate program over 10 years to adapt to the growing number and changing needs of pharmacy educators in the next generation.

DESIGN

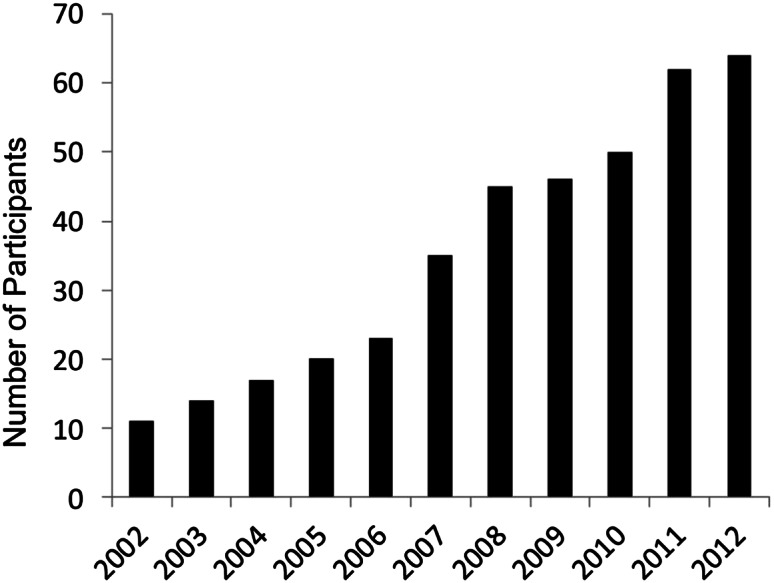

The Indiana Pharmacy Teaching Certificate (IPTeC) Program was initially developed and designed by a first-year Purdue University/Eli Lilly drug information specialty resident as a residency project. The objective of this project was to implement a multifaceted teaching certificate program involving classroom and experiential training to better prepare local pharmacy residents and fellows to be effective teachers. The resident performed an initial literature review of existing teaching certificate programs, surveyed area residents to gauge preliminary interest in such a program, and also consulted with local residency program directors and the Purdue University Center for Instructional Excellence. The program was first offered to 11 Indianapolis-based residents from 6 area institutions in spring 2003. Since that time, the number of residents and participating institutions has continually increased (Figure 1). In 2012, 18 institutions from across the state of Indiana had residents participating in IPTeC.

Figure 1.

Number of Participants in the Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate, 2002 to 2012

In 2006, IPTeC program directors collaborated with Butler University, the only other area college or school of pharmacy at the time. Since that time, Butler and Purdue Universities have continued collaborating to ensure the continued success of the IPTeC program. Two program directors are affiliated with Butler University and 2 are affiliated with Purdue University. From 2003 through 2009, IPTeC directors were successful in obtaining $10,000 annually in grant funding through a drug manufacturer. This monetary support helped provide speaker honoraria, continuing education accreditation costs, videotaping equipment, and photocopying costs. From 2009 through 2011, grant funding was denied but the program was sustained through monetary contributions from both participating universities to support speaker honoraria and photocopying costs.

Program requirements include attending classroom seminars on a variety of teaching topics as well as completing various teaching experiences. Each participant is required to perform at least two 60-minute lectures either as a classroom setting or as part of a continuing education program. An additional 15 hours’ experience in other teaching activities, such as precepting students, facilitating small-group case discussions, and serving as a teaching assistant, is also required. Participants are required to submit a teaching portfolio, which is reviewed by a faculty member from Butler University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences or Purdue University College of Pharmacy.

Previously published data regarding residents who had completed the IPTeC program from 2003 through 2006, indicated that 80% of respondents would recommend the program to future residents. Overall, graduates of the IPTeC program agreed that the seminars and the teaching experiences helped them in their current position.6 Over the last decade, the number of program participants has almost tripled, and the program has expanded to include a structured mentor program, distance learning, and continuing education credits. These advancements, combined with new challenges, such as decreased grant funding, technology limitations, scheduling conflicts, and new generational learning styles, highlighted the need for the program to be evaluated and redesigned. This paper provides an overview of the IPTeC program and assessment of its redesign over the last decade for the purpose of adapting to the needs of the next generation of pharmacy educators.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

In 2011, as part of a quality assurance assessment, the program directors developed a 25-item electronic survey instrument, which asked respondents to rank the importance of specific program requirements and activities using a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from very important=1 to not important=5. Similarly, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with positive statements describing program strengths and logistic issues using a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from strongly agree=1 to strongly disagree=5.

In April 2011, an electronic invitation containing a hyperlink to the survey instrument was sent to all residents enrolled in the teaching certificate program. Qualtrics Research Suite software (Qualtrics Lab, Provo, UT) was used to design and distribute the survey instrument electronically as well as to maintain confidentiality of all responses. A similar survey instrument was concurrently sent to all Indiana residency program directors who had residents enrolled in the program. Participants were assured that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Two reminder e-mails were sent to encourage participation and to maintain an adequate response rate. The project was approved by the local Investigational Review Board and received exempt status for human subjects research. All data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

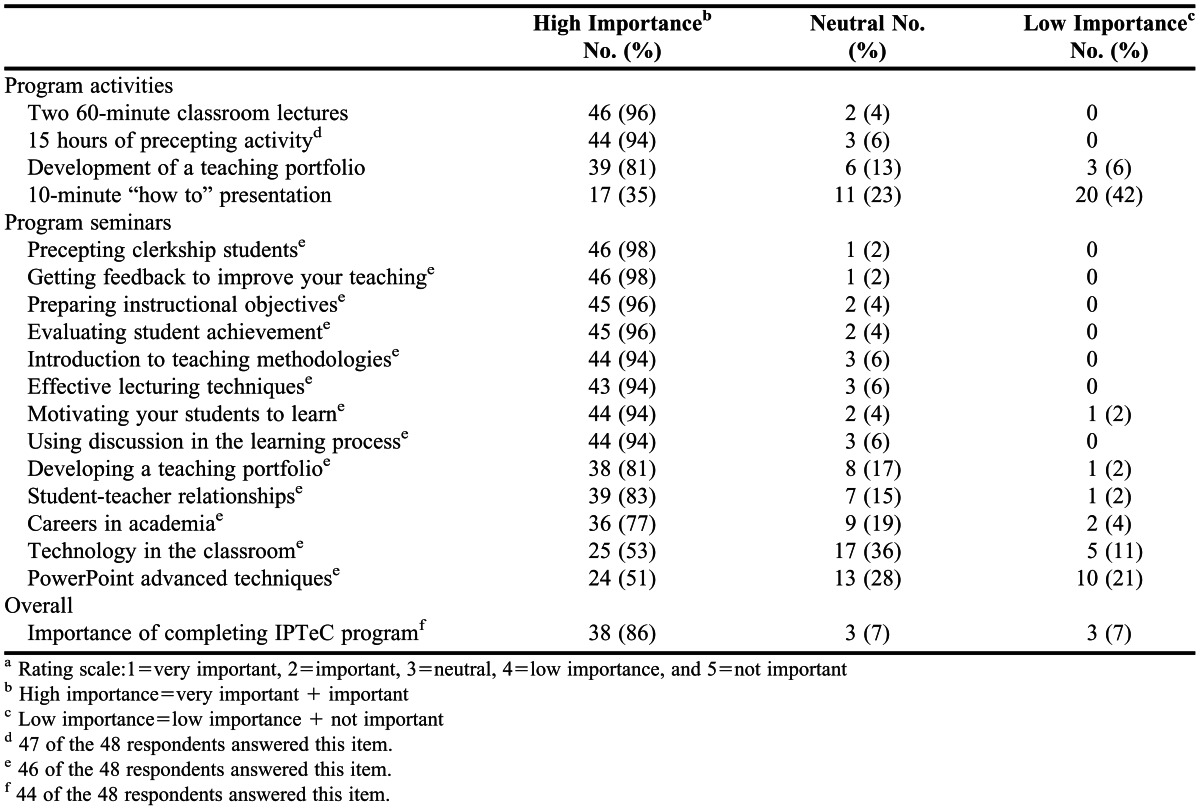

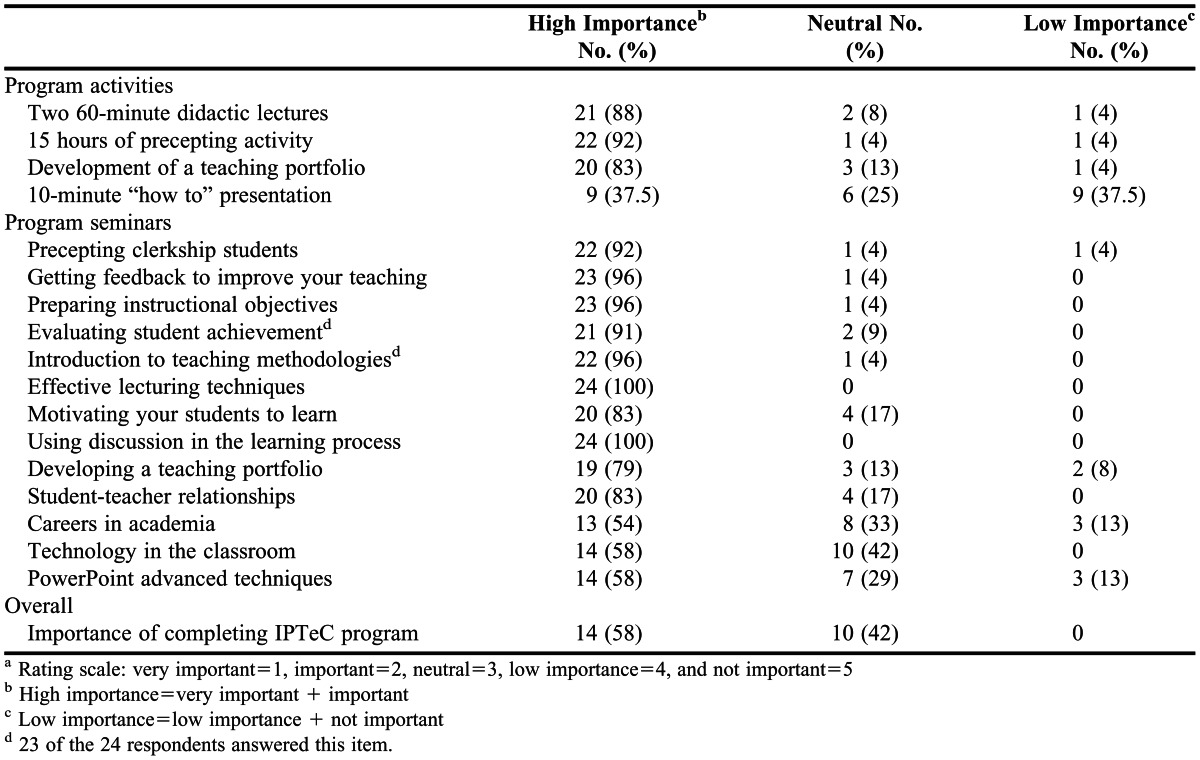

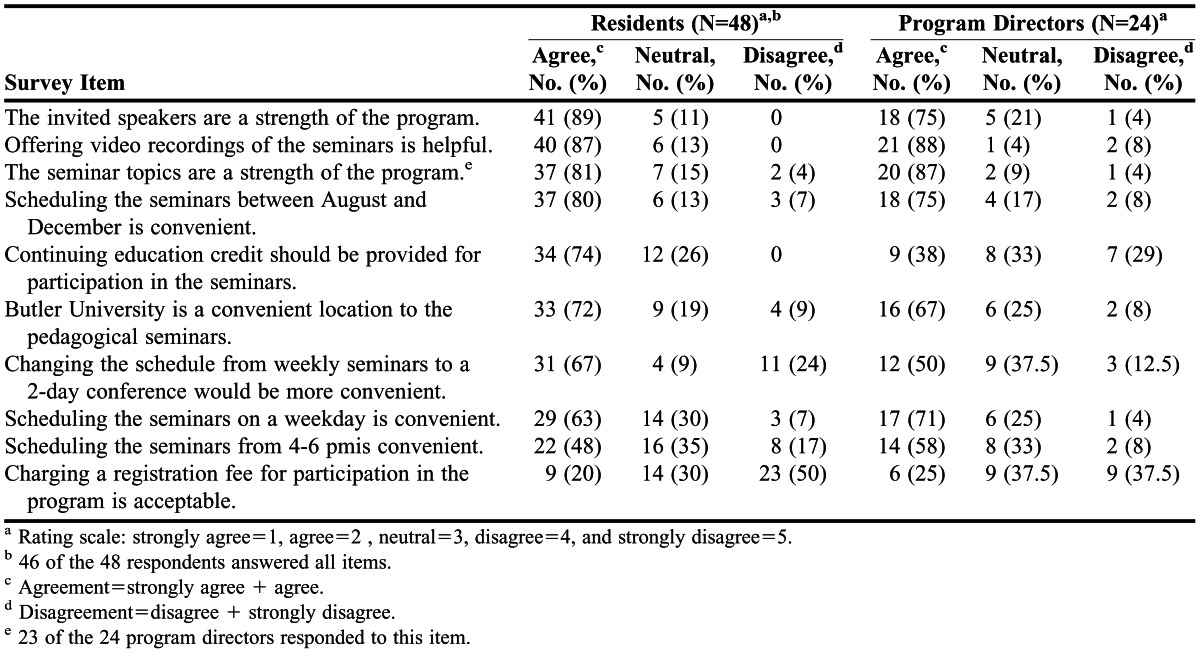

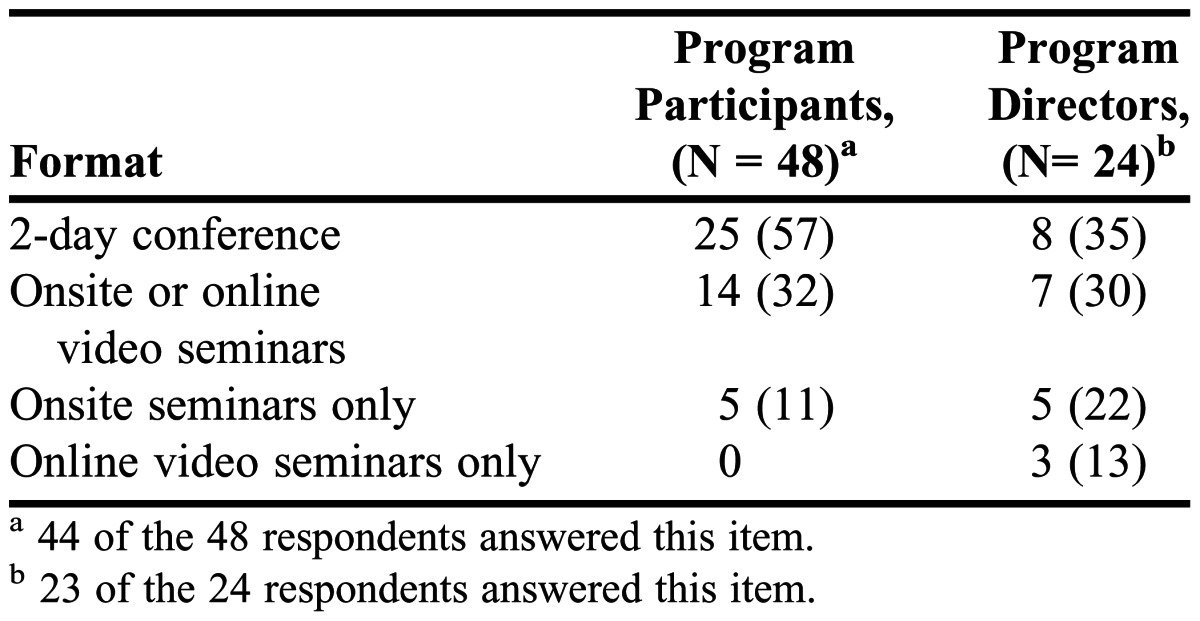

Forty-eight program participants and 24 program directors completed the survey instrument, providing response rates of 96% (48/50) and 71% (24/34), respectively. The majority of participants (69%) who responded to the survey instrument were affiliated with first-year pharmacy (PGY1) residencies, followed by second-year pharmacy (PGY2) residencies (13%) and fellowship and graduate programs (18%). Forty-six percent (11/24) of the program directors responding to the survey instrument reported that completion of the program was a residency requirement. More than 80% of program participants and directors perceived all of the required program activities to be very important or important, with the exception of the 10-minute how-to presentation, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. Program seminars that were considered to be of high importance by more than 90% of program participants and directors included precepting clerkship students, getting feedback to improve their teaching, preparing instructional objectives, evaluating student achievement, introducing teaching methodologies, using effective lecturing techniques, and using discussions in the learning process. Careers in academia, technology in the classroom, and Microsoft PowerPoint advanced techniques were perceived as highly important by a smaller percentage of program participants and directors. The importance of program completion was perceived as high by 86% (38/44) of program participants and 58% (14/24) of program directors. With respect to perceptions of the program’s strengths and logistic issues, participants generally agreed that the invited speakers, seminar topics, video recordings of seminars, and scheduling of seminars during the fall semester were strengths of the program. Only 20% (9/46) of program participants and 25% (6/24) of program directors agreed that charging a registration fee for participation in the program would be acceptable. Further details are presented in Table 3. Finally, as shown in Table 4, the 2-day conference was the program format most preferred by both program participants and directors.

Table 1.

Residents’ Perceptions of the Importance of the Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate Program Requirements and Activities (N=48)a

Table 2.

Program Directors’ Perceptions of the Importance of the Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate (IPTeC) Program Requirements and Activities (N=24)a

Table 3.

Residents’ and Program Directors’ Perceptions of the Strengths and Logistic Issues of the Indiana Pharmacy Resident Teaching Certificate

Table 4.

Program Format Most Preferred by Program Participants and Directors

Results of the 2011 quality assurance assessment were used to implement revisions to the program. Consistent with previous program offerings, participants are required to attend all classroom seminars, develop a teaching portfolio, deliver a minimum of two 60-minute classroom lectures, and document at least 15 hours of other teaching activities, such as precepting pharmacy students. Program participants have the option of fulfilling the lecture requirement as either a classroom lecture or as part of a continuing education program. The teaching activities requirement may be accomplished through precepting students, facilitating small-group case discussions, or acting as a teaching assistant. At the conclusion of the program, participants receive a certificate of completion, as well as 15 hours of continuing education credit.

The most significant program changes were implemented beginning with the 2011-2012 residency year. Program participants were charged an early registration fee of $75 or a late registration fee of $100. The implementation of the registration fee did not result in a decreased number of program participants. This monetary support helped provide conference meals and snacks, speaker honoraria, and program materials. For the first time, online registration and payment were available for incoming residents and fellows. Additionally, the seminars were condensed to a 2-day conference format in September 2011, compared with the previous format, in which seminars were offered every other week throughout the first half of the residency year. Eleven different classroom seminars were offered from 6 reputable, experienced faculty members from Butler and Purdue Universities and The University of Illinois at Chicago.

In previous years, 13 classroom seminars have been offered through the program. Based on survey results, program directors and past participants did not perceive the “Advanced Microsoft PowerPoint Techniques” seminar to be as important as other seminars; therefore, it was eliminated. The “Getting Feedback to Improve Your Teaching” seminar was also eliminated. Although this seminar was perceived to have higher importance according to survey results, the program directors found that most faculty members discussed effective ways to solicit feedback as related to the individual classroom seminars. All other seminar topics were maintained, based on survey results indicating they were considered important. The conference was offered at 1 central location near downtown Indianapolis. Participants were given the option to submit their teaching portfolios either electronically or as a paper copy. Electronic portfolio submission was a new requirement for 2012-2013 IPTeC participants.

All classroom seminars were recorded using Panopto (Panopto Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) technology available through Butler University. These recordings were subsequently posted on a shared online Web site for participants to access throughout the year, along with other relevant program materials. Additionally, participants were required to select a teaching mentor for the program to assist in presentation writing, group facilitation, examination question writing, and overall teaching guidance. Program participants were allowed to select a teaching mentor from a list of volunteers or to choose a mentor of their choice. Teaching mentors were required to have significant teaching experience, although faculty status was not a requirement. Mentors assisted with the midpoint review of the portfolio, which was subsequently reviewed by a faculty member prior to program completion.

DISCUSSION

The high response rate obtained from the assessment survey increased the validity of the data the authors had collected informally about necessary program updates and changes. Generally, responses from program participants and directors were consistent with respect to the perceived value and strengths of the program. One notable difference was in the percentage of participants who indicated that completion of the program was either very important or important, compared with that of program directors (86% vs 58%, respectively). This difference could be attributable to the fact that residency program directors are typically focused on clinical practice and may not put a high emphasis on teaching skills.

The survey instrument had limitations. The items regarding perceived importance, program strengths, and logistic issues were not forced by the survey software, which resulted in differing response rates for each question, potentially skewing the results. Additionally, because responses from PGY1 and PGY2 residents were not delineated, potential differences in responses based on participants’ level of experience could not be identified.

With the increasing number of pharmacy residents and growth in the number of residency programs, other teaching certificate programs may experience an increase in enrollment similar to that reported for this program. As our program expanded, it became logistically difficult to meet the scheduling demands of each individual participant. Participation in weekly programming became increasingly challenging because of responsibilities at the clinical site or in other residency obligations. By changing the format to a 2-day conference, residents were able to devote their full attention to the topics presented without the added distraction of having to leave their practice site, potentially disappointing their preceptors by leaving work unfinished.

With the loss of grant funding to support the costs associated with the program, other avenues were explored to offset expenses. Initially, there was some concern that implementation of a registration fee for the residents would deter resident participation. Despite only 20% of program participants and 25% of program directors surveyed expressing support for a registration fee, it was deemed necessary to sustain the program offering. After the fee was implemented with the 2011-2012 residency class, participation in the program has continued to steadily grow, with the 2012-2013 class being the largest to date. The program coordinators will revisit the registration fee each year to determine if modifications are needed to account for any increase in costs to maintain the program.

A structured mentor/resident pairing was developed and implemented to ensure that the residents received feedback throughout the program instead of just at the end during portfolio submission. Residents were responsible for selecting a mentor who best embodied the type of effective instructor and preceptor they hoped to become. A list of faculty members and preceptors who had teaching experience and had agreed to serve as mentors was sent to program participants struggling to identify a mentor. Having the residents find their own mentors, as opposed to assigning them, avoided the forced nature of a mentor-mentee pairing and allowed them to select mentors with whom they shared a common clinical interest and teaching philosophy. Mentors were given evaluation forms to use for providing midpoint feedback on the Web site. Pharmacy faculty members from Purdue and Butler Universities continue to provide formal portfolio evaluation and feedback in the revised format, as this feedback was an essential piece in the inception of the program.

Directors of established or new programs who are considering restructuring to accommodate an increase in resident numbers but do not want to sacrifice quality for quantity should conduct a quality-assurance assessment of area residents and residency directors. This assessment would help them determine if an alternative format would be a viable option in place of a traditional weekly program or consecutive seminar series throughout the residency year. Space in accommodating residents is necessary and can be achieved by using the resources of local colleges of pharmacy with adequate classroom space and technology available. The authors recommend selecting a time early in the residency-training year, such as August, so residents can use the skills and techniques they learned early in their teaching experiences.

An American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy 2002 task force recommended that formalized training programs for residents should focus on teaching, research design, and grant writing.8 In future years, consideration will be given to the development of additional classroom seminars that focus on research design and grant writing. The addition of another conference day will likely be necessary to accommodate additional speakers and presentations on these topics. Given that program participants do not reconvene later in the residency year as a group, directors will consider a wrap-up final session for upcoming offerings of the program. This session will provide participants the opportunity not only to discuss their teaching-related experiences throughout the year but also to review and discuss important aspects of the teaching portfolio.

SUMMARY

With the growing numbers of pharmacy residents and residency programs, teaching certificate programs must be able to accommodate a larger number of participants while continuing to provide quality instruction, faculty mentorship, and opportunities for classroom presentations and student precepting. Modifications over the last 10 years have enabled the program to successfully adapt to an increase in demand without sacrificing quality in the programming offered. As demand continues to change, the program will be continually evaluated and modified to maintain excellence in teaching. Directors of existing or new teaching programs should consider conducting a survey of current residency directors and residents to explore other avenues for restructuring current formats to meet these demands.

REFERENCES

- 1.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Brandt BF. Certificate program in teaching for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2001;58(10):868–898. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.10.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Brandt BF. Teaching residents how to teach: a scholarship of teaching and learning certificate program (STLC) for pharmacy residents. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2):Article 20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castellani V, Haber SL, Ellis SC. Evaluation of a teaching certificate program for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2003;60(10):1037–1041. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.10.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falter RA, Arrendale JR. Benefits of a teaching certificate program for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(21):1905–1906. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNatty D, Cox CD, Seifert CF. Assessment of teaching experiences completed during accredited pharmacy residency programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):Article 88. doi: 10.5688/aj710588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gettig JP, Sheehan AH. Perceived value of a pharmacy resident teaching certificate program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):Article 104. doi: 10.5688/aj7205104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manasco KB, Bradley AM, Gomez TA. Survey of learning opportunities in academia for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2012;69(16):1410–1414. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee M, Bennett M, Chase P, et al. Final report and recommendations of the 2002 AACP task force on the role of colleges and schools in residency training. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article S2. [Google Scholar]