Abstract

Objective. To use a drug information center training module to teach evidence-based medicine to pharmacy students and to assess their satisfaction with the experience.

Design. During the 5-week module, students were taught how to develop information search strategies and to conduct critical analysis of scientific papers. The instructors developed activities based on past requests received by the university’s Drug Information Center. The complexity of the assignments increased throughout the module.

Assessment. One hundred twenty-one students were trained between August 2009 and July 2010. Sixty-seven (55.4%) completed a voluntary assessment form at the completion of the 5-week module. Students’ feedback was positive, with 11 students suggesting that the module be integrated into the undergraduate curriculum. The most frequently (52.2%) mentioned area of dissatisfaction was with the performance of computers in the computer laboratory.

Conclusions. The drug information center training module was an effective tool for teaching evidence-based medicine to pharmacy students. Additional research is needed to determine whether graduates are able to apply the knowledge and skills learned in the module to the pharmacy practice setting.

Keywords: evidence-based practice, pharmacy students, drug information

INTRODUCTION

One of the challenges in providing quality health services is bridging the gap between best practices (established through scientific research) and the actual clinical care delivered.1 To provide the best treatment to patients, decisions should be based on the best available evidence. In order to provide the best treatment for patients, decisions should be based on the best available evidence, taken from studies with good methodology, that provide relevant information on clinical practice.2,3

Evidence-based medicine has emerged with the goal of helping healthcare professionals make better decisions with regard to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease in patients. All healthcare settings now have this approach as the original concept of evidence-based medicine has been extended to evidence-based healthcare.3

Evidence-based clinical guidelines have become the main reference for health care providers.1 However, several studies have suggested that health care providers do not actually use these guidelines. Approximately 10% to 40% of patients do not receive care based on updated scientific evidence and more than 20% of interventions performed are not required or are potentially harmful to patients.1,4 A strategy to reduce these shortcomings in the delivery of care is to increase the number of qualified health care professionals with knowledge of evidence-based practice. Actually, this training is already included in the curriculum3 of some medical undergraduate and postgraduate courses, but is lacking from the curricula of most other health professions schools, including pharmacy.

Some strategies were created at the Federal University of Bahia to introduce pharmacy students to evidence-based medicine practices. Initially, in 2008, classes on the drug information center, information search strategies, and evidence-based medicine were given to students in the computer laboratory of the faculty of pharmacy, during the first week of the pharmacy internship. In 2009, this approach was modified to enhance the learning process. Following these experiences, an evidence-based medicine training module used by the drug information center was developed and integrated into the pharmacy internship. The resulting 5-week course was called the Drug Information Center Training Module. This article describes the experience of training pharmacy students at the university in information search strategy, critical analysis of scientific papers, and evidence-based medicine knowledge, and then assessing the students' satisfaction with the training module.

DESIGN

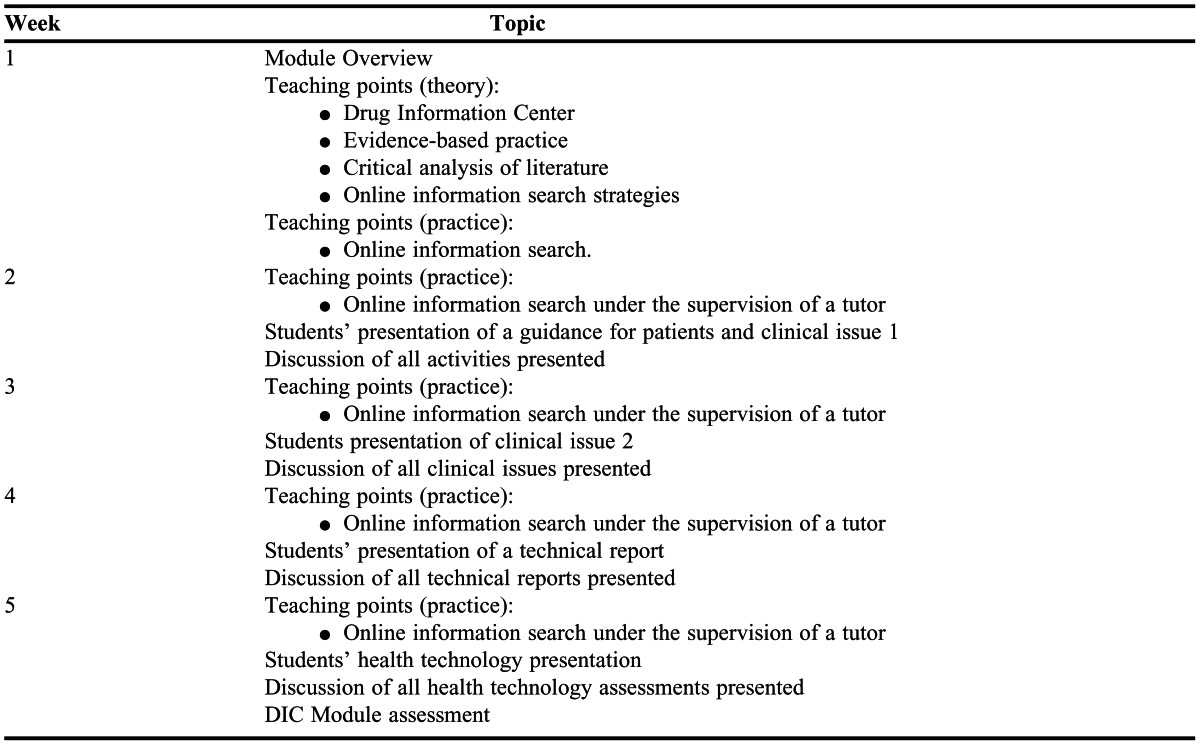

The course was conducted by a tutor (pharmacist from the Drug Information Center) for 2 semesters (August 2009 to July 2010) at the Professor Edgard Santos University Hospital and the computer laboratory of the pharmacy faculty at the university. At the beginning of each semester, students were divided into 4 groups of 13 to 17 students each. Five weeks (150 hours/semester) were required for each group to complete the training module. Theory and practice classes were conducted during the first week of the module. For the remaining 4 weeks, presentations on the module outcomes were held 3 days per week and online literature searches were performed by the students during the remaining 2 days of the week (Appendix 1). These meetings lasted 6 hours per day.

The presentations during the first week were about the drug information center and its activities in promoting the rational use of drugs, as well as presentations on evidence-based healthcare practice, such as the critical analysis of each scientific research methodology, the sources of information available at CAPES (Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - http://www.periodicos.capes.gov.br/), and the use of each search tool. Tutorials on all online databases used in the course were made available in Moodle (a distance learning education support software) to provide students with support in using secondary and tertiary resources. Students had access to the CAPES portal through the university’s virtual private network and could perform searches at any time and from any location.

The next 4 weeks included discussions and presentation of assignments. Each student had a weekly assignment to work on (2 assignments in the second week). The level of complexity of the activities gradually increased, building on knowledge students’ acquired as they progressed through the module.

Regarding assessment, students had to complete: (1) resolution of 2 clinical issues involving patient or population; (2) a written technical report; (3) a written rapid health technology assessment; and (4) guidelines for patients on the use of a specific drug. The students had 1 week to complete each activity.

The topics and content for all assignments were based on past information requests received by the drug information center. Technical reports (selection of evidence-based drugs) and health technology assessments were based on past requests received by the Health Secretariat of the State of Bahia, as well as the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee of the Professor Edgard Santos University Hospital.

Technical reports and health technology assessments are documents to support the decision making of managers at hospitals or health secretariats (government agencies). The basic difference between these 2 types of documents is the presentation of the final recommendation in favor or against the technology assessed, when possible, ie, the technical report does not include recommendations.

During the course, students learned to: (1) turn a practical issue into a research issue (using the PICO5 technique [Problem, Intervention, Comparator/Control, Outcome]); (2) use information sources (Micromedex, UpToDate, PubMed, Cochrane, Bireme, Scopus and Web of Science) find relevant information; (3) critically assess evidence (focused on the study methodology); and (4) generate plausible answers to apply to the case of a particular patient or population, that is, they were empowered to make decisions based on best evidence and prepared to discuss current clinical practice. The specific learning objectives for the course are outlined in Appendix 2. Throughout the semester, students answered questions of increasing complexity, from routine concerns encountered in clinical practice to indications for new treatments to use in treating rare diseases.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

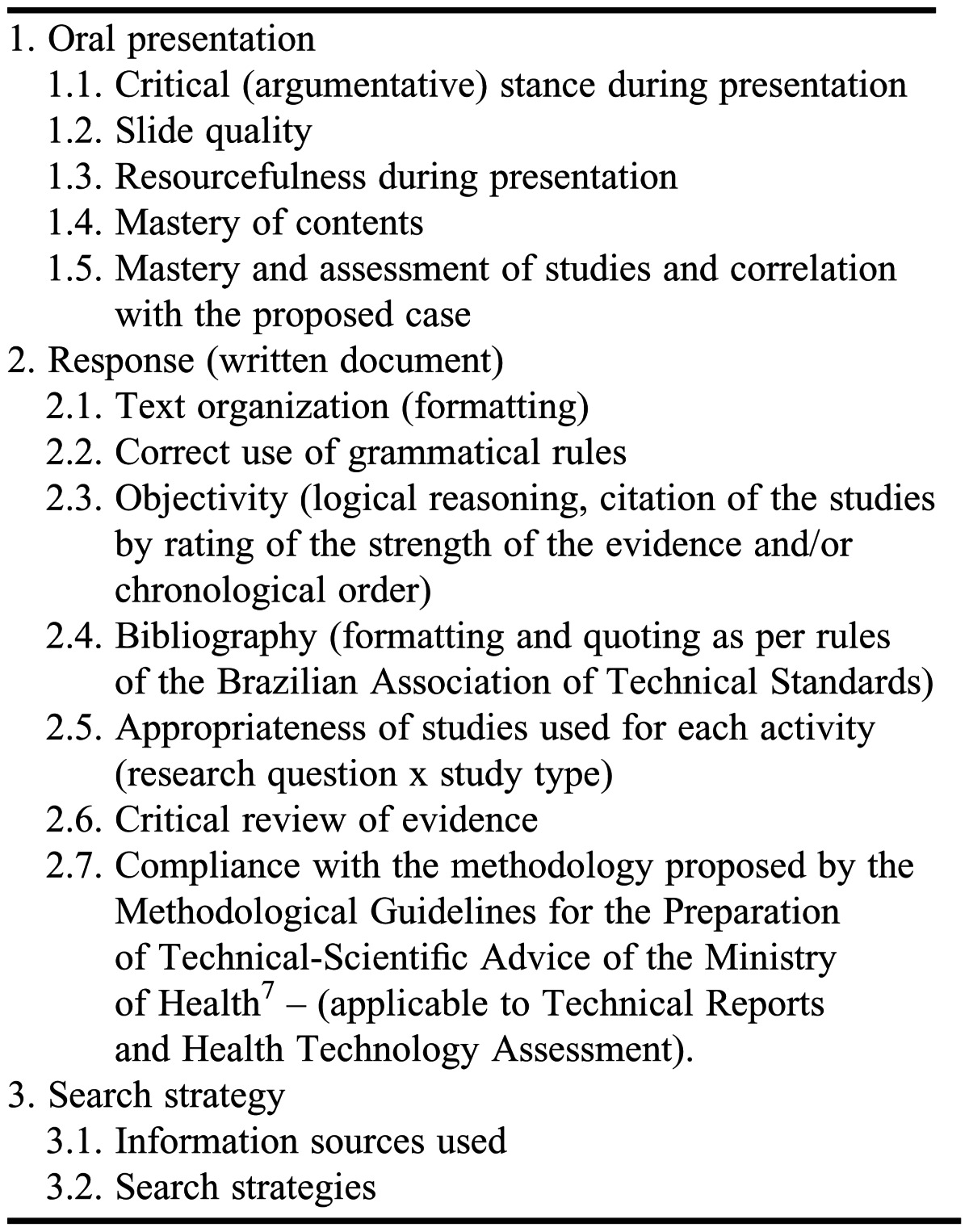

Each student delivered a 20- to 30-minute presentation on each activity and was assessed according to the criteria presented in Table 1. Students also were required to submit a 3-page report on each clinical issue, a10-page technical report, and a 10-page paper on providing health technology assessment. The value of an activity in terms of assessment was commensurate with its level of difficulty.

Table 1.

Activities Assessment Criteria

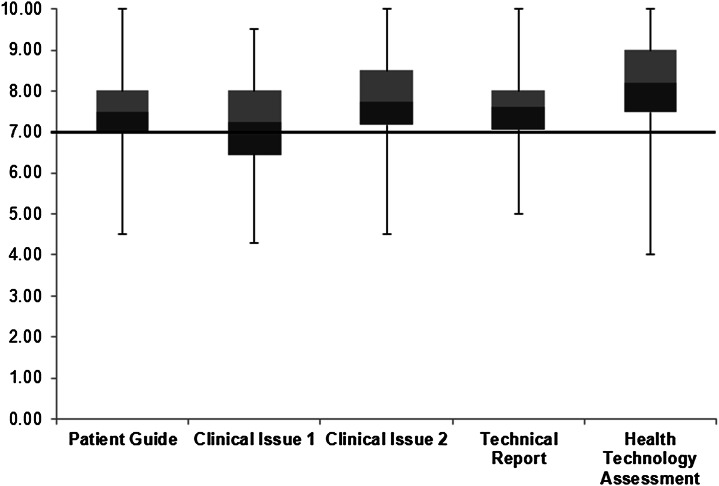

One hundred twenty-one students were trained from August 2009 to July 2010 (67 in the second half of 2009 and 54 in the first half of 2010). Each student completed 5 activities during the module, for a total of 590 assessed activities over the 2 semesters. A box plot was created with the grades achieved by all students for each activity (Figure 1). Grades of zero (given when student did not perform the activity) were discarded and penalties for late submission of work were removed so that only the grade reflecting performance on the activity was included in the analysis. The resulting graph was used to assess the overall progress of the group throughout the module.

Figure 1.

Grades of pharmacy students on activities completed as part of a 5-week drug information module .

Students’ median grade on all activities was higher than 7 (indicates that the activity goals were achieved). The highest median grade was an 8.2 and was achieved on the last activity, health technology assessment. A declining trend was observed when the assigned activity was changed, ie, the students’ median grade decreased when the complexity of the activity increased, as seen between the patient guidance assignment and the first clinical issue assignment. On the other hand, an increase in the median grade was noted in activities that required similar skills and knowledge (eg, increase in median score from clinical issue 01 to clinical issue 02). When the median grades for the assignments were tracked over the weeks of the module, these fluctuations in median grades became clear: guidance for patients, score 7.5; clinical issue 01, score 7.3; clinical issue 02, score 7.7; technical report, 7.6. Moreover, in all activities, except the first clinical issue, 75% or more of the students achieved a grade over 7. Students’ mean grades on the activities were similar to median grades (guidance for patients, 7.5 ± 1.0 ; clinical issue 1, 7.1 ± 1.0 ; clinical issue 2, 7.7 ± 1.1 ; technical report, 7.6 ± 0.9 ; health technology assessment, 8.1 ± 1.2).

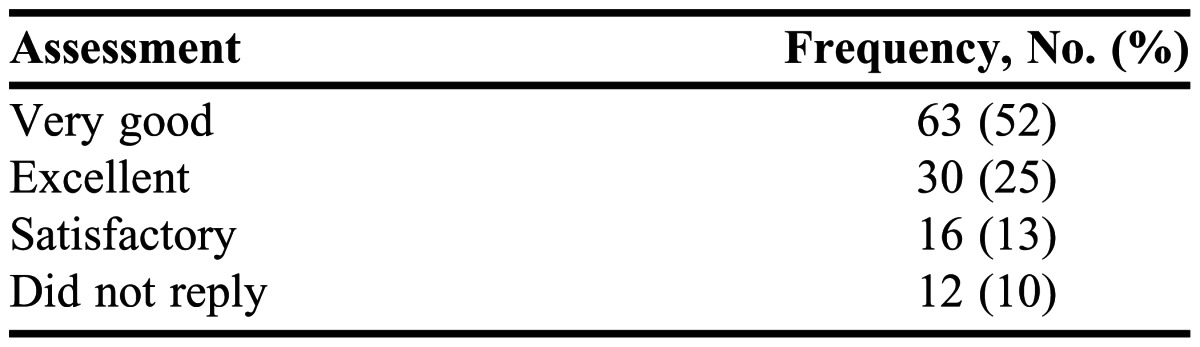

At the end of the 5-week training module, an assessment form was distributed to students to rate their level of satisfaction with the program’s content and with the tutor’s guidance; and to self-assess their participation and performance on the course assignments. The response scale for each question ranged from 1 to 5 (1 = null/nonexistent, 2 = poor, 3 = satisfactory, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent). The form also included a section for written suggestions and assessments of strengths and weaknesses of the module. The assessment form was anonymous and its completion was not mandatory.

Of the 121 students trained, only 67 (55.4%) completed the module assessment form. Students’ feedback regarding whether the content fulfilled the stated objectives for the module was positive, with 85% rating it excellent or very good.

Students’ self-assessment of their performance in the activities was mostly good (Table 2) and no student rated his or her performance as 0 or unsatisfactory. The tutor’s guidance in the course was rated as excellent by 37% of the students, very good by 30%, satisfactory by 12%, and nonexistent by 3%; 18% of the students did not reply to this section.

Table 2.

Pharmacy Students’ Self-Assessment of Their Participation and Performance in the Activities

In the written comments, the suggestion to include the module as a permanent part of the undergraduate curriculum was mentioned 11 times (16.4%). Moreover, students' perceptions of the importance of the module in future activities as a professional, the course methodology, and the skills acquired were positive.

The most often mentioned area of dissatisfaction (52.2%) was with the performance of computers in the computer laboratory of the pharmacy faculty. Other areas of dissatisfaction mentioned by students included that the module was tiring (11.9%), there were too many daily presentations (6%), the time allowed to perform the activities was insufficient (9%), the length of the course was short compared to the volume of information presented (7.5%), and the activities were intense (1.5%).

DISCUSSION

In a 2008 study by the authors, the contents of the training module was presented in 3 class sessions and students were assessed on their use of evidence-based medicine principles based on their reports on 3 modules (drugstore, compounding pharmacy, and hospital pharmacy), as well as on their presentations on various activities during the rest of the pharmacy internship. However, that strategy was not effective because students were not able to apply their knowledge of evidence-based practice. This finding was based on the assessments of the presentations of pharmacovigilance cases, clinical cases, and academic reports elaborated during the internship.

In an attempt to improve the quality of learning, in the first half of 2009, the module was taught during the first 2 weeks of the semester and students were asked to detect relevant clinical issues in the various practice environments mentioned above. Students’ learning was improved, but still did not meet expectations. Although pharmacy students demonstrated that they were able to find, retrieve, and evaluate clinical studies, they were not able to apply the information extracted from the studies to real practice.

Effective learning occurs when students are able to correlate theory with practice. This means that they are able to make connections between the knowledge gained in one setting and apply it to another.8 Teaching pharmacy students to critically read and appraise literature so they are able to update their knowledge base throughout their professional life is essential. The constantly expanding body of literature adds another level of complexity to the efficient and accurate identification of studies and their assessment.9

Because of the ineffectiveness of the approach used in 2008, beginning in 2009, a 5-week Drug Information Center Training Module was developed, that included more frequent assessments and used problem-based learning methods. This module was kept as part of the pharmacy internship, but continued over a longer period of time (5 weeks).

Although not all students completed the non-mandatory assessment form distributed at the end of the module, it was possible to assess the program. Furthermore, at the end of the 5 weeks, an oral evaluation of the module and a self-assessment of the students was conducted.

Most of the students self-assessed their performance in the course as very good and felt their knowledge and skills improved as a result of completing the 5-week module. The effectiveness of the drug information training module was demonstrated by the consistency of the grades, with the majority of grades above 7.

A decrease in grades was noted when a new type of activity was performed in the course. On the other hand, when a more complex activity that involved the same development process as the previous activity was performed, the students’ grades probably increased as a result of knowledge learned from the previous activity. Moreover, most of the students considered the tutor’s guidance in the course to be excellent, thus justifying having a tutor present throughout the module to oversee the activities.

Training pharmacy students in the practice of evidence-based medicine is more relevant than training pharmacy professionals, according to the results of the systematic analysis of Norman and Shannon.10 Bookstaver and colleagues9 assessed the impact of a 2-hour evidence-based medicine elective course aimed at teaching third-year students to critically assess medical literature and apply these skills in patient decision-making. Prior to this course, students were exposed to skills related to the recovery and interpretation of literature and formulating answers to clinical issues during 2 semesters of curricular drug information courses (introductory and advanced). The majority of the students said that the fundamentals learned in the course were most valuable to their success during their practice experiences.

Neil and Johnson11 presented an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) through a 4-week course to third-year pharmacy students. The students developed skill needed to apply an evidence-based approach to population-level practice decisions. Pretesting and posttesting were used to assess the impact of this course.

Ten students completed the evidence-based medicine APPE over a 3-year period. Students’ mean score on application of principles related to biostatistics and information mastery increased 15.8% from pretest to posttest. Mean scores for course evaluation components ranged from 4.8 to 5.0 on a 5-point Likert scale, where 5 = excellent and 1 = poor. This approach was considered an excellent opportunity to enhance students’ understanding and appreciation of the application of evidence-based medicine principles.11 One of the limitations of our study is that we did not administer a pretest to assess student’s skills and knowledge before completing the module. Doing so could have increased the reliability of using this method to train pharmacy students.

Several evidence-based medicine teaching strategies have been described and the duration of class schedules varies widely, ranging from 15 minutes to several years.1 However, this diversity of methods needs to be assessed to better establish which ones are the most effective, as well as the course length that will yield the best results. Although some students in our study characterized the drug information center training module as tiring, others seemed to recognize the need for this type of training to become better-qualified professionals because they suggested that the module become part of the undergraduate curriculum or be made available to students before they begin their pharmacy supervised internship. Incorporating the content of the training module into the required curriculum might increase students’ skills and knowledge and eliminate the perceptions that the module does not allow sufficient time to complete all activities and is tiring.

Another weakness of the module was the poor quality of the computers in the computer laboratory of the pharmacy faculty. This was a serious deterrent to learning because each student needed a computer with a fast Internet access in order to perform the evidence-based medicine activities12 for the training module.

Although various health sectors already incorporate evidence-based practice, and some medical undergraduate and postgraduate courses include this teaching in their curriculum,3 few health professionals were presented with these concepts prior to graduation and only learn them through postgraduate courses.

The skills used in the acquisition, interpretation, and application of evidence-based medicine practices are only taught formally in a required course in 42% of colleges and schools in the United States. However, many of the college and school representatives surveyed felt that these principles should be incorporated into the curriculum to a greater degree.9

The lack of courses in the undergraduate curricula in Brazilian universities that address evidence-based medicine concepts is worrisome because patient care usually is provided by several healthcare professionals and all should agree on the best approach to care. With the shift towards a multidisciplinary approach to patient care, pharmacists will play a key role in evidence-based decision making, and provide scientifically valid information as the expert on best practices in the appropriate use of drugs.9

The Brazilian Network of Services and Drug Information Centers (REBRACIM - http://rebracim.webnode.com.br/) published a report on the potential of some Brazilian Services and Centers with regard to meeting the demands of the Brazilian Public Health System and contributing to the training of professionals.13, Some drug information centers report teaching activities such as unpaid internships or scholarships14; however, there is no description of the contents covered in these activities or their workload. Furthermore, little is achieved with this strategy, as few students can be trained according to this approach.

Thus, completing a drug information training module or course prior to graduation could educate a larger number of future pharmacists in this important area. Moreover, it seems to be a more effective approach to teaching best practices than through continuing education courses for professionals or residents.1,10

Evidence-based medicine training has been given to all professionals from the university’s Multidisciplinary Residency. (The multidisciplinary residency program at our institution is composed of pharmacists, nurses, dentists, physical therapists, social workers, nutritionists, psychologists, and audiologists.) Plans are to make a drug information course a permanent part of the program’s curriculum.

Students felt they were better prepared for their future role as pharmacists because of the knowledge and skills acquired in the module. A follow-up study should be performed to determine whether the students are able to apply the skills and knowledge learned in the drug information training module after they enter the professional work environment.

CONCLUSION

The 5-week evidence-based drug information training module enhanced students’ knowledge and skills as well as their ability to apply clinical evidence to actual information requests. Students’ assessment of the drug information module was positive. This learning approach of incorporating a 5-week module into undergraduate pharmacy education was effective because students assessed themselves as successful in the performance of their activities, their grades increased throughout the semester, and they requested that the module become a permanent part of the curriculum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all of the alumni of the Drug Information Center Training Module who contributed their comments and suggestions for its improvement and growth, in particular, Gabriella Fernandes Magalhães, for her contributions to the contents and review of the paper. They also express their gratitude to Dr. John Kessler, Chairman of the Institutional Review Board University, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA – for his equally valuable contribution and review of the paper.

Appendix 1.

Drug Information Center (DIC) Training Module Outline

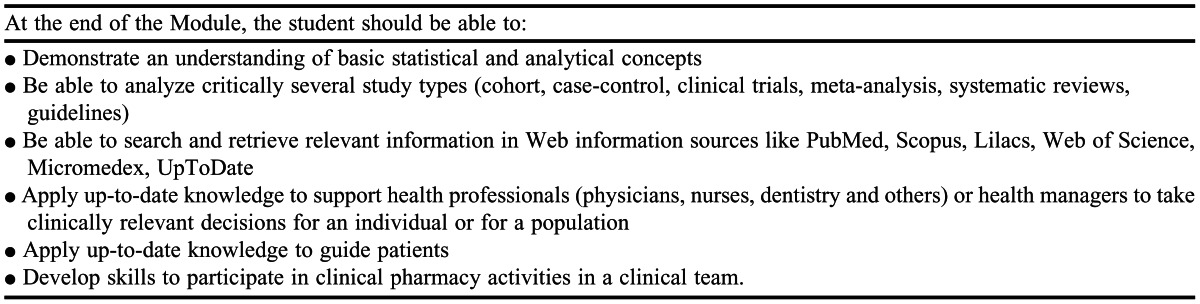

Appendix 2.

Drug Information Center Training Module – Learning Objectives

REFERENCES

- 1.Flores-Mateo G, Argimon JM. Evidence based practice in postgraduate healthcare education: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(July):119–126. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopes AA. Medicina baseada em evidências: a arte de aplicar conhecimento científico na prática clínica. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 2000;46(3):285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macedo CR, Riera R, Atallah NA. Aperfeiçoamento em saúde baseada em evidências por teleconferência. Diagn Tratamento. 2009;14(1):42–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patient’s care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1125–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research, 3rd ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2008. 544p. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. Assistência farmacêutica na atenção básica: instruções técnicas para sua organização. 2 ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2006. 100p. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. Diretrizes Metodológicas: elaboração de pareceres técnico-científicos. 2 ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009. 62p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thangaratinam S, Barnfiel G, Weinbrenner S, et al. Teaching trainers to incorporate evidence-based medicine (EBM) teaching in clinical practice: the EU-EBM project. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(September):59–66. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bookstaver PB, Rudisill CN, Bickley AR, et al. An evidence-based medicine elective course to improve student performance in advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe7519. Article 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman GR, Shannon SI. Effectiveness of instruction in critical appraisal evidence-based medicine) skills: a critical appraisal. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;158(2):177–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neil KK, Johnson JT. An advanced pharmacy practice experience in application of evidence-based policy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(7) doi: 10.5688/ajpe767133. Article 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Alessio R, Busto U, Girón N. Información de Medicamentos. Guía para El Desarrollo de Servicios Farmacéuticos Hospitalarios. Serie Medicamentos Esenciales y Tecnologia, 1997; 54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. Rede Brasileira de Centros e Serviços de Informação sobre Medicamentos: potencialidades e perspectivas. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2012. 104p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castilho SR, Paula FA, Souza SS, Futuro DO, Bokeni JR. Centro de apoio à terapia racional pela Informação sobre medicamentos: relato de 5 anos de atividades. In: VIII Congresso Ibero-americano de extensão universitária, Rio de Janeiro. November, 2005. [Google Scholar]