Abstract

Catalytic enantioselective allyl-allyl cross-coupling of a borylated allylboronate reagent gives versatile borylated chiral 1,5-hexadienes. These compounds may be manipulated in a number of useful ways to give functionalized chiral building blocks for asymmetric synthesis.

Recent advances in the palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of allyl electrophiles and allyl boronates have provided an effective strategy for the enantio- and diastereoselective construction of chiral 1,5-hexadienes.1,2 A central feature of this reaction is that with appropriately selected ligands, the transformation proceeds by way of a stereoselective 3,3′-reductive elimination that delivers the branched 1,5-hexadiene as the predominant reaction product.3,4 While enantioselective allyl-allyl couplings have been developed that facilitate the construction of 1,5-hexadienes bearing single tertiary or quaternary centers, or that possess adjacent tertiary stereocenters, considerable limitations remain. A foremost barrier to the use of allyl-allyl coupling as a tool for molecular assembly lies in the development of general strategies for differentiation of the product alkenes. In isolated cases, selective functionalization of the 1,5-diene can be accomplished by exploiting steric bias in the substrate; however, this is not a reliable site-selective tactic. To more directly address this issue, we considered that installation of a functional group handle on one of the allyl coupling partners might provide a more versatile product motif with well-differentiated alkenes. Herein, we describe a highly enantioselective allyl-allyl cross-coupling reaction that utilizes bis(boryl) nucleophile 1 (Scheme 1), such that 3,3′-reductive elimination (i.e. 2→3), delivers a borylated 1,5-hexadiene framework 3.5 These products may be manipulated in a number of ways and should enhance the utility of allyl-allyl cross-coupling in asymmetric synthesis.

Scheme 1.

Catalytic allyl-allyl cross-coupling with bis(boronate) 1.

To implement the cross-coupling strategy described above requires ready access to allylic boronate 1. While 1 is available by diboration of allene using 3 mol % Pt(PPh3)4 at 80 °C as reported by Miyaura6 (Table 1, entry 1), we sought a procedure that is more amenable to large scale synthesis. Ideally, access to 1 would arise by a procedure that uses low loadings of commercially available catalysts and, given the low boiling point of allene (−34 °C), would not require elevated temperatures. Our first experiments examined lower catalyst loadings on larger scale and revealed that excellent yields could be obtained with 0.3 – 0.6 mol % Pt catalyst (entries 2 and 3). Further investigation found that Pd complexes are also effective and, with as little as 0.25 mol % Pd2(dba)3 and 0.6 mol % PCy3, the reaction could be run at room temperature and still proceed efficiently.7 Most importantly, when run on preparative scale these reactions provide excellent isolated yield of 1, a shelf-stable compound that was readily purified by distillation.

Table 1.

Synthesis of 1 by Catalytic Diboration of 1,2- Propadiene.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | temp (°C) | scale (mmol) | yield (%)b |

| 1a | 3% Pt(PPh3)4 | 80 | 1 | >98 |

| 2a | 0.3% Pt(PPh3)4 | 80 | 20 | 88 |

| 3a | 0.6 % Pt(PPh3)4 | 80 | 40 | >98 |

| 4c | 2.5% Pd2(dba)3; 6% PCy3 | rt | 10 | >98 |

| 5d | 0.25% Pd2(dba)3; 0.6% PCy3 | rt | 24 | >98 |

Excess allene was used and reactions were carried out in a high pressure vessel.

Value is for the isolated yield of purified material and is an average of two experiments.

Reaction was run in a round bottom flask, under positive N2 atmosphere.

1.5 equiv of allene was employed.

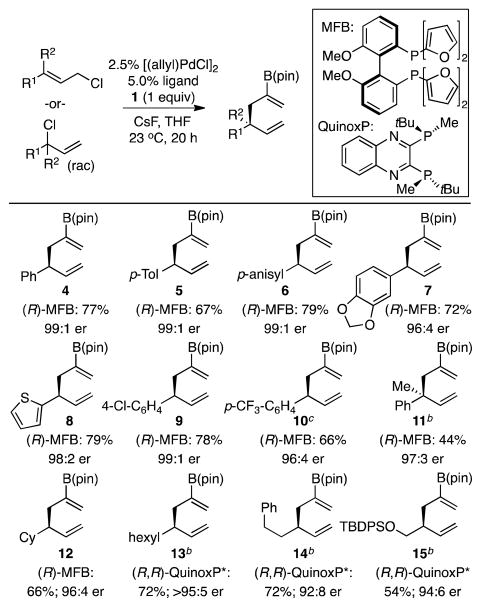

To investigate the allyl-allyl cross-coupling with 1, cinnamyl chloride was chosen as a probe substrate. After some tuning (Pd precursor and additives), it was found that excellent reactivity and enantioselectivity could be achieved using [(allyl)PdCl]2 and (R)-methoxyfurylbiphep8 as the catalyst system. With these conditions, borylated 1,5-hexadiene 4 was isolated in 77% yield and 99:1 enantiomer ratio (Scheme 2). It merits mention that the level of enantioselectivity observed between cinnamyl chloride and 1 is substantially higher than that which is observed between unsubstituted allylB(pin) and cinnamyl electrophiles. The scope of the allyl-allyl cross-coupling was further examined as depicted in Scheme 2. These studies revealed that both electron-rich and electron-poor aromatic substrates performed equally well under the reaction conditions (Scheme 2, 5–10) and were converted to the derived product with high enantiopurity and good yields. Diene 8 is of particular note as this example demonstrates that sulfur-containing heterocycles, prevalent structures in medicinally relevant targets, are not necessarily detrimental to the reaction. The examples in Scheme 2 also demonstrate that stereoisomeric mixtures of allylic chlorides can be processed in the coupling and provide high yields of single-isomer products. In addition, the scope of cross-couplings employing 1, was found to extend to the enantioselective production of borylated 1,5-hexadiene 11, a compound bearing an all-carbon quaternary center.

Scheme 2.

Asymmetric Allyl-Allyl Cross-Coupling of Allylboronate 1 and Allylic Chlorides.a

(a) All yields are average of two experiments. Linear E-allylic chloride substrates were used for 4–8. A mixture of linear and branched allylic chloride substrates was used for 10–14. Linear Z-allylic chloride used for 15. (b) Reaction was carried out at 60 °C, 24 h, and in 20/1 THF:H2O. (c) This compound was isolated as a ca. 5:1 mixture along with the linear diene isomer.

Examination of aliphatic substrates showed that while a cyclohexyl-substituted allylic chloride reacted smoothly to give 12 under the conditions described above, when other aliphatic allylic chlorides were examined, elimination to 1,3-dienes was the predominant reaction pathway. Supposing that generation of 1,3-dienes occurred by β-hydride elimination from intermediate π-allyl complexes, other catalysts were examined. Consistent with previous observations,1a,1c the merged influence of (R,R)-QuinoxP*9 as a ligand and THF/H2O as solvent system minimized β-hydrogen elimination and allowed for the preparation of linear alkyl-substituted products in high enantioselectivity and good yields (13–15).

While it was found that the borylated dienes in Scheme 2 could be isolated and purified by silica gel chromatography, it was also of interest to examine their direct conversion to other motifs. In one experiment, allyl-allyl cross-coupling was followed by treatment with NaOH and H2O2; methyl ketone 16 was isolated in 78% yield (Scheme 3, eq. 1).10 Alternatively, the allyl-allyl cross-coupling could be followed by Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling employing S-Phos as the ligand.11 In this experiment, additional palladium catalyst was not required for the second step; the palladium employed for the allyl-allyl coupling suffices for the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction and delivered styrene derivative 17 in 78% yield (Scheme 3, eq. 2).

Scheme 3.

Enantioselective allyl-allyl coupling with 1, and its utility in cascade reactions.

MFB = 2,2′-dimethoxy-6,6′-bis(di-2-furylphosphino)biphenyl, S-Phos = 2-Dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl.

In addition to the transformations in Scheme 3, a variety of additional transformations using purified boronate 4 were examined to further probe the utility of the borylated allyl-allyl coupling products (Scheme 4). Copper mediated halogenation of 2 was found to deliver vinyl halides 18 and 19, in 85 and 80% yield, respectively.12 Alternatively, using conditions developed by Merlic, the vinyl boronate 4 could be smoothly transformed to the derived enol ether 20 in 71% yield.13 In addition to transformation of the boronate, it was found that the steric differentiation of the two alkenes was sufficient to enable chemoselective catalytic cross-metathesis with ethyl acrylate; this furnished α,β-unsaturated ester 21 in 63% yield as a single olefin isomer.14 This cross-metathesis is particularly useful as it leaves the vinyl boronate in place for subsequent transformation. Lastly, it was found that OsO4-catalyzed dihydroxylation, in the presence of 2 equivalents of NMO, selectively transforms the borylated alkene, leaving the non-borylated alkene untouched (4→22). In this case, it appears that the Bpin group is sufficiently electron-releasing that the vinyl boronate reacts faster than the non-borylated olefin.15

Scheme 4.

Transformations of vinylboronate 4.

A significant feature of cross-coupling reactions involving 1 is the enhanced level of enantioselectivity relative to cross-coupling with allylB(pin). For example, as illustrated in equation 3 (Scheme 5), when trifluoromethyl-substituted cinnamyl carbonate 23, was subjected to allyl-allyl cross-coupling with allylB(pin), the cross-coupling product was obtained in 74% ee; however, when the analogous coupling was performed with 1, the enantioselection was substantially higher (92% ee). We propose a stereochemical model depicted by A (Scheme 5) to rationalize the significant enhancement of er. In this model, the allyl-allyl coupling occurs through a chair-like six-membered transition structure where the chair conformation is dictated by the ligand chirality. In the transition structure leading to the minor enantiomer, the pendant B(pin) group may introduce an additional interaction with the pseudoequatorial furyl ring leading to an enhancement in selectivity relative to the non-borylated nucleophile.

Scheme 5.

Model for enhance stereoselectivity in allyl-allyl coupling using 1

In conclusion, we have described the catalytic enantioselective allyl-allyl cross-coupling that provides versatile vinyl boronate products. Further studies on the utility of these transformations in asymmetric synthesis are under way.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support by the NIGMS (GM- 64451) and the NSF (DBI-0619576, BC Mass. Spec. Center) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank AllyChem for a donation of B2(pin)2.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Complete experimental procedures and characterization data (1H and 13C NMR, IR, and mass spectrometry). This material is free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For enantioselective allyl-allyl cross coupling, see: Zhang P, Brozek LA, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10686. doi: 10.1021/ja105161f.Zhang P, Le H, Kyne RE, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9716. doi: 10.1021/ja2039248.Brozek LA, Ardolino MJ, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16778. doi: 10.1021/ja2075967.

- 2.For linear selective allyl-allyl couplings, see the following: Allylstannanes: Trost BM, Keinan E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:2595.Godschalx J, Stille JK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:2599.Goliaszewski A, Schwartz J. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:5028.Keinan E, Peretz M. J Org Chem. 1983;48:5302.Trost BM, Pietrusiewicz KM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:4039.Goliaszewski A, Schwartz J. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:5779.Goliaszewski A, Schwartz J. Organometallics. 1985;4:417.Keinan E, Bosch E. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4006.Cuerva JM, Gomez-Bengoa E, Mendez M, Echavarren AM. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7540.van Heerden FR, Huyser JJ, Williams DBG, Holzapfel CW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5281.Nakamura H, Bao M, Yamamoto Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:3208. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010903)40:17<3208::AID-ANIE3208>3.0.CO;2-U.Homoallylic alcohols: Sumida Y, Hayashi S, Hirano K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2008;10:1629. doi: 10.1021/ol800335v.Allylboronates: Flegeau EF, Schneider U, Kobayashi S. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:12247. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902221.Jimenez-Aquino A, Flegeau EF, Schneider U, Kobayashi S. Chem Commun. 2011;47:9456. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13348a.

- 3.For examples of 3,3′-reductive eliminations applied to allyl-allyl systems, see: reference 1 and Mendez M, Cuerva JM, Gomez-Bengoa E, Cardenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Chem Eur J. 2002;8:3620. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020816)8:16<3620::AID-CHEM3620>3.0.CO;2-P.Cardenas DJ, Echavarren AM. New J Chem. 2004;28:338.Perez-Rodriguez M, Braga AAC, de Lera AR, Maseras F, Alvarez R, Espinet P. Organometallics. 2010;29:4983.

- 4.For operation of 3,3′-reductive elimination in other processes, see: Keith JA, Behenna DC, Mohr JT, Ma S, Marinescu SC, Oxgaard J, Stoltz BM, Goddard WA., III J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11876. doi: 10.1021/ja070516j.Sieber JD, Liu S, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2214. doi: 10.1021/ja067878w.Sieber JD, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4978. doi: 10.1021/ja710922h.Sherden NH, Behenna DC, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:6840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902575.Zhang P, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12550. doi: 10.1021/ja9058537.Trost BM, Zhang Y. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:296. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902770.Chen J-P, Peng Q, Lei B-L, Hou X-L, Wu YD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14180. doi: 10.1021/ja2039503.Ardolino MJ, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8770. doi: 10.1021/ja302329f.Keith JA, Behenna DC, Sherden N, Mohr JT, Ma S, Marinescu SC, Nielsen RJ, Oxgaard J, Stoltz BM, Goddard WA., III J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:19050. doi: 10.1021/ja306860n.

- 5.For the use of 2-silylallylsilane reagents in synthesis, see: Fleming I, Taddei M. Synthesis. 1985;9:899.Pernez S, Hamelin J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:3419.Boukherroub R, Manuel G, Weber WP. J Organomet Chem. 1993;444:37.Overman LE, Renhowe PA. J Org Chem. 1994;59:4138.Laclef S, Exner CJ, Turks M, Videtta V, Vogel P. J Org Chem. 2009;74:8882. doi: 10.1021/jo901878b.For the use of 2-stannylallylstannane reagents in synthesis, see: Mitchell TN, Schneider U, Heesche-Wagner K. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:969.Mitchell TN, Schneider U, Heesche-Wagner K. J Organomet Chem. 1991;411:107.Curran DP, Yoo B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6931.Piers E, Kaller AM. SynLett. 1996:549.Williams DR, Meyer KG. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:765. doi: 10.1021/ja005644l.Britton RA, Piers E, Patrick BO. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3068. doi: 10.1021/jo030389j.Bukovec C, Wesquet AO, Kazmaier U. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:1047.

- 6.Ishiyama T, Kitano T, Miyaura N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2357. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For palladium catalyzed diboration of substituted allenes, see: Yang FY, Cheng CH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:761. doi: 10.1021/ja005589g.Pelz NF, Woodward AR, Burks HE, Sieber JD, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16328. doi: 10.1021/ja044167u.Burks HE, Liu S, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8766. doi: 10.1021/ja070572k.

- 8.Broger EA, Foricher J, Heiser B, Schmid R. 5,274,125. US Patent. 1993

- 9.Imamoto T, Sugita K, Yoshida K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11934. doi: 10.1021/ja053458f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For alternate approaches to compounds similar to 16, see: Shekhar S, Trantow B, Leitner A, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11770. doi: 10.1021/ja0644273.Weix DJ, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7720. doi: 10.1021/ja071455s.Jung B, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1490. doi: 10.1021/ja211269w.

- 11.(a) Walker SD, Barder TE, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:1871. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4685. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy JM, Liao X, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15434. doi: 10.1021/ja076498n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Shade RE, Hyde AM, Olsen JC, Merlic CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1202. doi: 10.1021/ja907982w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Winternheimer DJ, Merlic CA. Org Lett. 2010;12:2508. doi: 10.1021/ol100707s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Garber SB, Kingsbury JK, Gray BL, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8168. [Google Scholar]; (b) Blackwell HE, O’Leary DJ, Chatterjee AK, Washenfelder RA, Bussman DA, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:58. [Google Scholar]; (c) Morrill C, Grubbs RH. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6031. doi: 10.1021/jo0345345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Morrill C, Funk TW, Grubbs RH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:7733. [Google Scholar]

- 15.For related osmium-catalyzed dihydroxylation of vinylsilane: Richer JC, Pokier MA, Maroni Y, Manuel G. Can J Chem. 1978;56:2049.Hudrlik PF, Hudrlik AM, Kulkarni AK. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4260.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.