Abstract

Background

Small conductance calcium activated potassium channels (SKCa) are voltage insensitive and are activated by intracellular calcium. Genome wide association studies revealed that a variant of SKca is associated with lone atrial fibrillation (AF) in humans. Roles of SKca in atrial arrhythmias remain unclear.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine roles of SKCa in atrial arrhythmias.

Methods

Optical mapping using isolated canine left atrium was performed. The optical action potential duration (APD) and induction of arrhythmia were evaluated before and after the addition of specific SKCa blockers, Apamin or UCL-1684.

Results

SKCa blockade significantly increased APD80 (188±19 ms vs 147±11ms, p< 0.001). The pacing cycle length (PCL) thresholds to induce 2:2 alternans and wave breaks were prolonged by SKCa blockade. Increased APD heterogeneity was observed following SKCa blockade, as measured by the difference between maximum and minimum APD (39±4ms vs 26±5ms, p<0.05), by standard deviation (12.43±2.36ms vs 7.49±1.47ms, p<0.001), or by coefficient of variation (6.68±0.97% vs 4.90±0.84%, p<0.05). No arrhythmia was induced at baseline by S1–S2 protocol. After SKCa blockade, 4 out of 6 atria developed arrhythmia.

Conclusion

Blockade of SKCa promotes arrhythmia and prolongs the PCL threshold of 2:2 alternans and wave breaks in the canine left atrium. The proarrhythmic effect could be attributed to the increased APD heterogeneity in the canine left atrium. This study provides supportive evidence of GWAS studies showing association of KCNN3 and lone AF

Keywords: Atrial arrhythmia, SKCa, action potential duration, repolarization, optical mapping

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and contributes to significant morbidity and mortality.1 Efficient pharmacological treatment for AF is currently limited and many approaches come with considerable risk of adverse effects. Numerous factors are involved in the pathogenesis of AF.2, 3 Specifically, genetic variations in ion channels that predispose to AF have been reported.2, 3 The structural and ionic remodeling during AF further leads to the complexity of AF studies. This raises the importance of understanding the role of ion channels in the genesis of AF.

Small conductance calcium activated potassium channel (SKCa) is voltage independent and is activated by intracellular calcium of submicromolar concentrations.4 SK family was first cloned by Adelman and his colleagues in 1996.5 It consists of three members (SK1, SK2, and SK3) and is characterized by the specific blockade by apamin.6 Although the calcium sensitivity (Kd= 0.6–0.7 μM) and conductance (9.2– 9.9 pS) are similar among three subtypes, the sensitivity to pharmacological modulation and tissue distribution differs.6–9 It has been shown that SK1 and SK2 are predominantly abundant in mouse atria while SK3 expresses equally in atria and ventricles.8 In humans, the distribution is different. SK2 and SK3 are more abundant than SK1 in atria.9 In the heart, SKCa plays an important role in action potential duration (APD), contributing to the cardiac repolarization current.7, 8 Despite the abundance of SKCa in the atrium, whether SKCa plays a role in atrial arrhythmogenesis remains unclear.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) showed two genetic variations of KCNN3 (gene encoding SK3) to be associated with lone AF.10, 11 One of those variations is an intronic single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and the other is a synonymous SNP. Although no amino acid is changed by these identified SNPs, it is possible that they are linked to an unidentified non-synonymous SNP in KCNN3 that leads to increased susceptibility of lone AF. Physiological evidence of a role for SKCa in atrial arrhythmia comes from studies on SK2.12, 13 A Potential relationship between SK2 expression and atrial remodeling in AF has been shown. For example, intermittent burst pacing in rabbit hearts increases SK2 mRNA and protein, and the trafficking of SK2 to membrane is increased which leads to increased apamin-sensitive current and shortened APD.12 Moreover, SK2 knock-out mice show prolonged APD and increased AF inducibility.13 To extend these previous studies to large animal models, we used normal canine atria to clarify the role of SKCa in atrial arrhythmogenesis. We hypothesize that SKCa plays a protective role in structurally normal atrium and SKCa blockade promotes arrhythmia.

Methods

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Indiana University School of Medicine and the Methodist Research Institute, Indianapolis, IN, and conforms to the guidelines of the American Heart Association.

Canine left atrial tissue preparation

Male mongrel dogs weighed 25–30kg were used in this study (N=9 for optical mapping, and N=5 for Western blotting). They were fully anesthetized by isoflurane and were euthanized to obtain hearts by thoracotomy. The atrial tissue preparation was performed as previously described with some modification.14 Briefly, the heart was harvested and perfused with cardioplegic solution. The cardioplegic solution was composed of (in mM): 129 NaCl, 12 KCl, 0.9 NaH2PO4, 20 NaHCO3, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.5 MgSO4, and 5.5 glucose. Left coronary artery was then cannulated through its aortic orifice. Subsequently, the right atria and the ventricles were surgically removed. All open vessels on the border of the remaining left atrial tissue were ligated. Afterwards oxygenated Tyrode’s solution was perfused through the left circumflex. The compositions of Tyrode’s solution was as follows (in mM): 125 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 24 NaHCO3, 1.8 NaH2PO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 5.5 glucose, and 2% bovine serum albumin, equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to maintain a pH of 7.4.

Optical mapping system

The perfusate was maintained at 37°C with a flow rate around 30 ml/min. After stabilizing the preparation, 10 μM voltage sensitive dye, RH237 was added to the perfusate along with 15 μM excitation-contraction uncoupler, blebbistatin. A laser light at 532 nm was used to excite the stained atrial preparation and fluorescence was collected using a CMOS camera (BrainVision, Tokyo, Japan). It recorded voltage fluorescence through a 710 nm long-pass filter. Fluorescence image was captured at frame rate with 2 ms/frame and at 100 × 100 pixels with spatial resolution of 0.35 × 0.35 mm2/pixel for 4s. To determine the rhythm of the atrium, pseudo-ECG was utilized. It was obtained with widely spaced bipolar electrode. The signals were filtered from 0.05 to 100 Hz, and digitized at 1 kHz with AxoScope.

Pacing protocol and Induction of atrial arrhythmia

A bipolar pacing lead was placed at the apex of the appendage with an output at 2.5 times the diastolic threshold. Optical recording was performed after 40 beats of stable pacing at each PCL. The pacing cycle length (PCL) was progressively shortened from 1500ms (1500ms, 1000ms, 800ms, 500ms, 450ms, 400ms, 350ms, 300ms, 280ms, 250ms, 220ms, 200ms, 190ms, 180ms, 170ms, 160ms, etc.) until loss of capture. After five minutes recovery, arrhythmia inducibility was evaluated by a S1–S2 protocol, consisting of continuous 9 beats S1 stimuli followed by an additional S2 beat. An episode with more than two extra beats resulted from reentry were regarded as a successful arrhythmia induction. The same procedure was repeated after 30 minutes of perfusion with 100 nM of apamin (Tocris Bioscience, MN, USA) or 100nM UCL-1684 (Tocris Bioscience, MN, USA). In this study, 5 atria were treated with apamin and 4 were treated with UCL-1684 respectively. The arrhythmia induction protocol was performed in 6 atria among the 9 atria that were optically mapped. Two atria were treated with apamin and four with UCL-1684 respectively.

Proteins Extraction

Left atrium appendage (LAA) was cut into 8 pre-defined pieces and homogenized by POLY-TRON in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (50 mM Tris pH 8.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 5 μg/ml aprotinin). Homogenates were incubated on ice for 30min and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes. After collection of the supernatant, protein concentration was quantified by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) using bovine serum album (BSA) as the standard.

Western blotting

Protein electrophoresis was done using Bio-Rad mini gel system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was bathed in TBS with 5% milk for one hour, and probed with anti-KCNN2 antibody (Abcam, ab83733, 1:2500) or anti-GAPDH antibody (Pierce, MA1-22670, 1:5000) overnight. Following primary antibody incubation, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma, 1:5000) for 30 min. Finally, Luminata Crescendo HRP substrate (Millipore, WBLUR100) was added on the membrane according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

Results were summarized by typical parameters such as mean± standard deviation and compared using ANOVA test or paired T test. Post-test comparison was conducted by Tukey test (one way) or Bonferroni test (two way). All statistics were calculated by Prism 5.0 (Graphad, CA, USA). P value less than 0.05 was regarded as statically significant.

Results

Effect of SKCa blockade on action potential duration

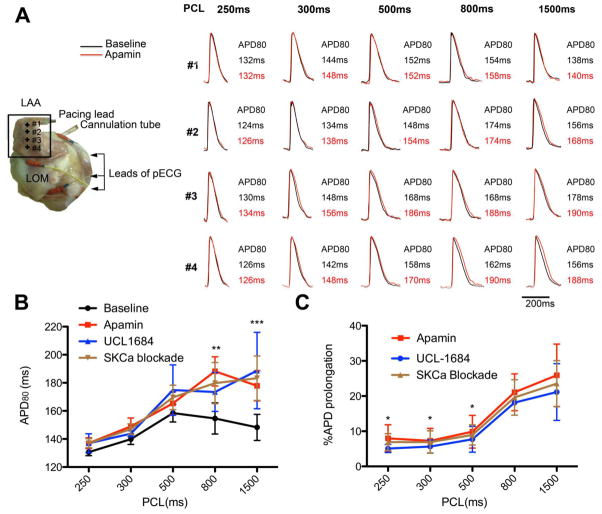

Pharmacological blockade of SKCa was used to study its role in atrial electrophysiology. SKCa blockade resulted in APD prolongation as observed by optical mapping. The experimental configuration of atrium preparation is shown in Figure 1A. Optical images were captured from the left atrium appendage (LAA). The relationship between APD80 and PCLs was shown is figure 1B and 1C. The differential effects of apamin and UCL-1684 did not show statistical significance (p=0.994 by ANOVA). A biphasic relationship between APD80 and PCLs was observed at baseline. APD80 increased proportionally to the PCLs at short and intermediate PCLs. The maximum APD80 occurred at the PCL of 500ms. APD80 gradually decreased as PCLs increased longer than 500ms. After SKCa blockade, APD80 was generally prolonged at all PCLs. The effect of SKCa blockade was more obvious at long PCLs (Figure 1B and 1C). At PCL of 1500ms, blocking of SKCa prolonged the APD80 from 147±11ms to 188±19ms (p< 0.001). However the APD80 at PCL of 250ms were comparable between baseline and SKCa blockade (129±2ms vs. 139±3ms). The percentage of prolongation at PCLs of 1500, and 250ms were 23.54±6.54%, and 6.91±2.40% respectively

Figure 1. Effect on atrium by SKCa blockade.

A. Configuration of isolated canine left atrium preparation and corresponding APD change. The black square identifies the optically imaged region. The corresponding APD is shown in the left panel. Note that the pattern of ADP prolongation is very heterogeneous. LOM, Ligament of Marshall. LAA, left atrium appendage. B. Relationship between PCL and APD80. A biphasic relationship between APD and PCL was observed at baseline. APD increased as PCL increased from 250ms to 500ms. When PCL was longer than 500ms, APD shortened. SKCa blockade abolished this phenomenon (N=9, 5 with apamin treatment and 4 with UCL-1684 treatment). Comparison was performed between baseline and SKCa blockade (apamin and UCL-1684). Star (*) denotes the post test p-values following ANOVA test. C. Percentage of APD prolongation by SKCa blockade at different PCLs. SKCa blockade showed a tendency to prolong APD in all PCLs. The effect was most significant at long PCLs. Star (*) denotes the p-values from post test when compared with 1500ms *, p<0.05, **, p< 0.01. ***, P< 0.001

Increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade

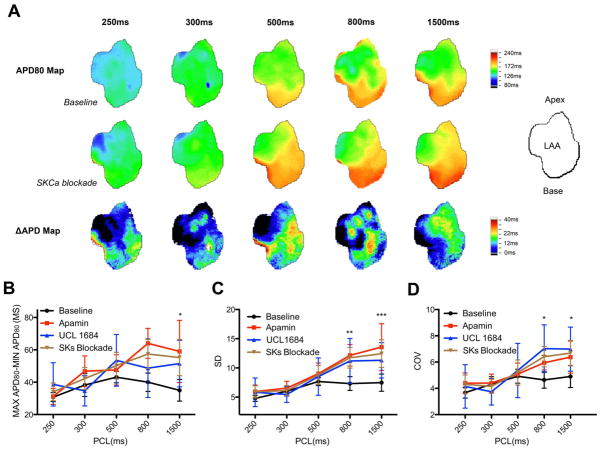

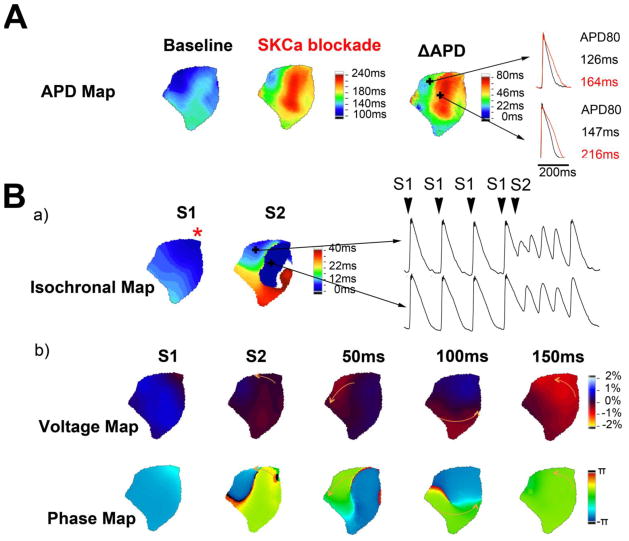

ADP heterogeneity has been recognized as an important mechanism contributing to reentrant atrial arrhythmia.15 The representative APD maps in figure 2A are evidence of increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade. Even at the baseline, APD was not homogeneous. The increased color gradient after SKCa blockade represents increased heterogeneity. To quantify the ADP heterogeneity, three different measurements were used. In the first measurement of APD heterogeneity, the maximum and minimum APD80 was calculated (Figure 2B). This difference was increased from 26±5ms to 39±4 ms after SKCa blockade (p< 0.05). Standard deviation (SD) generated from optically imaged region was used as the second method to measure ADP heterogeneity (Figure 2C). At baseline, the average SD was 7.49±1.48ms. After SKCa blockade, it was increased to 12.43±2.36ms (p< 0.001). The last measurement was to calculate the coefficient of variation (COV). This was used to determine the increased SD due to increased APD. Figure 2D showed that COV was also increased from 4.90±0.84% to 6.68±0.97% by SKCa blockade (p< 0.05). This suggested that increased SD by SKCa blockade did not simply result from increased APD but also from increased heterogeneity of APD. All three measurements showed statistically significant increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade.

Figure 2. Increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade.

A. Examples of APD map at different PCLs. The orientation of LAA is illustrated by the diagram. Increased APD heterogeneity is demonstrated by increased color gradient in APD maps after blockade by UCL-1684. ΔAPD reveals heterogeneous prolongation of SKCa blockade. B, C, and D. Quantification of APD heterogeneity. All three measurements indicate that SKCa blockade increases APD heterogeneity (N=9, 5 with apamin treatment and 4 with UCL-1684 treatment). Comparison was performed between baseline and SKCa blockade (apamin and UCL-1684). Star (*) denotes the post test p-values following ANOVA test. *, p< 0.05. **, P< 0.01. ***, P< 0.001

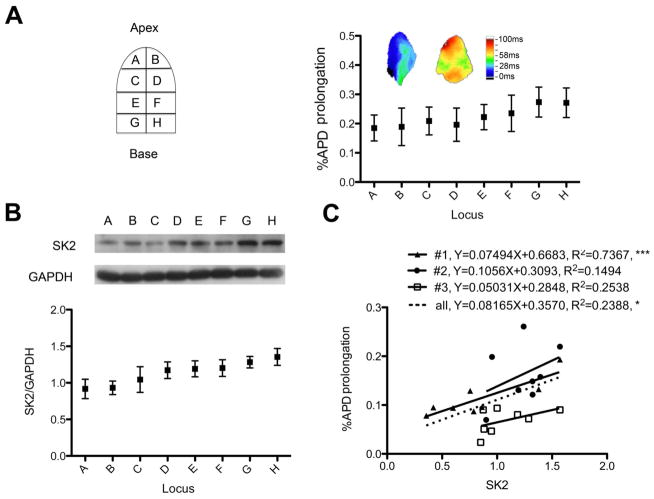

Detection of SK2 and its relationship to APD prolongation

LAA was divided into 8 regions to study the increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade (Figure 3A). APD maps from different animals showed different patterns of APD prolongation. Some atria showed significant APD prolongation while others showed little APD prolongation. Western blotting was used to quantify the distribution of SKCa. The distribution was shown in Figure 3B. After optical mapping, we collected three atria and analyzed the distribution of SK2 and the corresponding percentage of APD prolongation. When curve fitting was performed using all data points, the correlation was statistically significant with R2 equaling 0.2388 (p< 0.05), suggesting that SK2 participated in our observation of APD change.

Figure 3. Detection of SK2 and its relationship with APD prolongation.

A. Top left is an illustration showing the 8 predefined regions which the LAA was dissected into. Top right shows percentage of APD prolongation by SKCa blockade in different regions (n=9, 5 with apamin treatment and 4 with UCL-1684 treatment). Insets are representative ΔAPD maps from two different LAAs showing heterogeneous APD prolongation by SKCa blockade. B. SKCa protein expression at different regions (n=5). A representative Western blotting image is shown in the inset. C. Relationship of SK2 proteins and APD prolongation. The abundance of SK2 protein is plotted against the percentage of corresponding APD prolongation (n=3). Among them, #1 and #2 were treated with apamin while #3 was treated with UCL-1684. The formula and value of R2 are displayed. The plotting from all points yields a significant linear correlation with R2 equaling to 0.2388 (p= 0.0154). *, p< 0.05., ***, P< 0.001

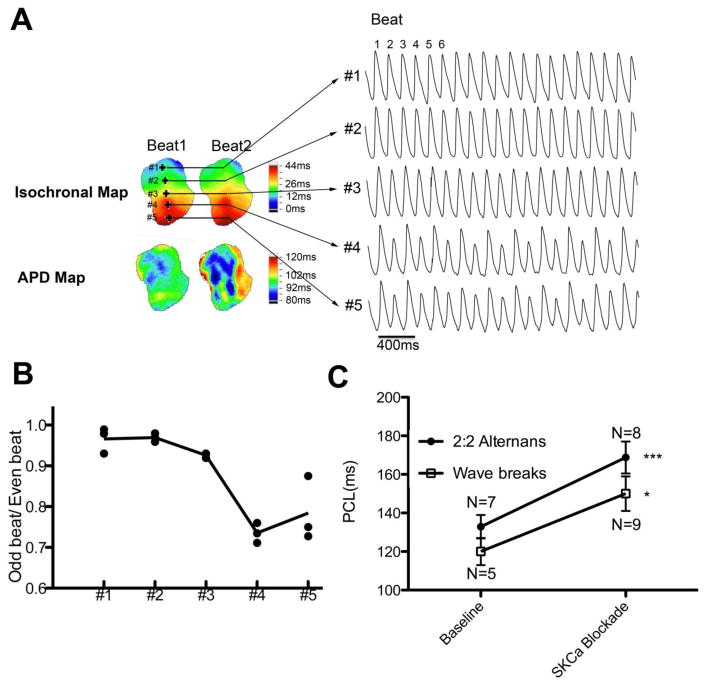

SKCa blockade facilitated development of 2:2 alternans and wave breaks

At rapid PCLs, loci with conduction delay were sometimes observed (Figure 4A) and this phenomenon was exaggerated by SKCa blockade. The 2:2 alternans initially occurred at regions of conduction delay and eventually spread throughout all regions of the LAA. Wave breaks were even observed in some atria when PCLs were further shortened. At baseline, five atria developed 2:2 alternans followed by wave breaks. Four showed 2:1 capture without any observation of wave breaks. After SKCa blockade, eight atria developed 2:2 alternans and all showed wave breaks at shorter PCLs. As shown in figure 4C, PCL threshold of for 2:2 alternans was significantly longer by the SKCa blockade (162±9ms vs 130±6ms at the baseline, p< 0.05). PCL threshold for wave breaks induction was also longer (153±11ms vs 118±9ms at the baseline, p< 0.05).

Figure 4. Development of 2:2 alternans and wave breaks.

A. Representative traces of 2:2 alternans. Data were acquired from an atrium at baseline. Corresponding isochronal maps and APD maps from beat 1 and beat 2 are shown. Note that there is a region showing conduction delay (#4 and #5). The site that developed 2:2 alternans lies within the region showing conduction delay. B. Ratio of consecutive beats showing conduction efficiency. Beat 2/beat 1, beat 4/beat3, and beat 6/beat5 from Figure 3A are plotted. The conduction efficiency decreases gradually from #1 to #5. C. SKCa blockade prolonged the PCL threshold of 2:2 alternans and wave breaks. Wave breaks could only be induced in 5 atria at baseline while it was induced in all atria after SKCa blockade. *, p< 0.05. ***, P< 0.001

SKCa blockade promoted development of reentrant arrhythmia

At baseline, we did not observe any episode of arrhythmia. Atrial arrhythmia could be induced in one out of two atria in the presence of apamin, and three out of four in the presence of UCL-1684. As a total, atrial arrhythmia could be induced in four out of six atria after SKCa blockade. Sustained arrhythmia was observed in one atrium treated with UCL-1684. Optical mapping revealed that arrhythmia emanated from local conduction block and led to the occurrence of reentrant arrhythmia (Figure 5). In panel A, the APD is heterogeneously distributed at baseline. After SKCa blockade, APD becomes more heterogeneous. This led to partial atrial activation by a premature stimulation (S2) given at the apical region (asterisk on isochrones map).

Figure 5. Induction of reentry arrhythmia by SKCa blockade.

A. APD maps and the corresponding ΔAPD map from the same atrium showing the pattern of APD change after SKCa blockade. Maps were generated from PCL of 1500ms. B. Representative arrhythmia induced by S1–S2 protocol. Additional pacing (S2) after a stimuli was used to induce arrhythmia. S1, regular pacing at 400ms, S2, additional pacing 160ms after a S1 pacing. No arrhythmia could be induced at baseline while 4 out of 6 atria developed arrhythmia after SKCa blockade. a) Isochronal maps showing the conduction patterns. Star symbol (*) indicates the pacing site. Only parts could be activated, as revealed by S2 isochrone. b) Corresponding voltage maps and phase maps. Arrows in voltage map show the propagation of reentry. Time label represents time interval after S2 pacing.

Discussion

SKCa blockade in canine atrium

In this study, we used two different SKCa blockers to study the role of SKCa in canine atria. The atrial APD prolonged after the addition of specific SKCa blockers. Western blotting showed the presence and a heterogeneous distribution of SK2. Apamin is an 18 amino acid peptide neurontoxin and is a classical SKCa blocker. It has been reported that apamin binds to S3–S4 loop of SKCa and acts as a pore blocker.16 UCL-1684 is a potent non-peptide SKCa blocker. It shares a similar mechanism as apamin through regulation of S3–S4 loop. However it exerts its effect by allosteric modulation without binding to S3–S4 loop.17 The application of blockers with different mechanisms reduces the risk of off-target effect. The results using apamin and UCL-1684 were comparable, suggesting that our observations come from specific SKCa blockade. Moreover the plotting of SK2 against percentage of APD prolongation yielded a statistically significant correlation. The value of R2 was small in such a correlation. This could be due to that SK2 is not the only SKCa in the atrium although it might be the most abundant.

Mathematical modeling of human atrial action potential using 12 different transmembrane currents has shown a biphasic relationship between APD and PCL.18 This resembles our observations of biphasic APD–PCL relationship at baseline. SKCa blockade transformed it into monophasic, suggesting the importance of SKCa in atrial APD regulation and APD adaption. SKCa blockade prolonged APD especially at long PCLs. This was consistent with our previous finding in failing rabbit ventricles (unpublished data). We have previously found that the effect of SKCa blockade is most obvious at very long and very short PCL. The effect of SKCa blockade is minimal at intermediate PCLs. This study does not compare APDs shorter than 250ms due to the occurrence of alternans. Theoretically, tachycardia would facilitate the accumulation of intracellular calcium that activates SKCa. Hence it would be expected to contribute to considerable cardiac repolarization power during tachycardia.

Ion channel remodeling during AF promotes APD shortening.3 It is generally accepted that pharmacologically prolonged APD might prevent AF. Interestingly, the results of SKCa blockade showed paradoxical effects. It promoted arrhythmia despite APD prolongation.

Increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade

We observed APD heterogeneity throughout the LAA. SKCa blockade significantly enhanced APD heterogeneity. Increased APD heterogeneity might lead to increased susceptibility of arrhythmia.15 Our finding clearly supports this phenomenon. After SKCa blockade, APD became more heterogeneous. When an additional stimuli (S2) was applied, only a few regions could be activated while the rest of LAA remained in effective refraction period (ERP). This led to an uneven pattern of atrial activation and eventual reentry arrhythmia.

Appearance of local conduction delay and arrhythmia induction

The occurrence of 2:2 alternans was reported to be the result of diffusion current between regions of 1:1 capture and 2:1 capture.19 Although we could not identify any regions with 2:1 capture within the optically imaged area, we found that there were certain regions that showed conduction delay during rapid pacing. The occurrence of 2:2 alternans initiated from these regions and spread to the other regions if PCLs was further reduced. Blockade of SKCa aggravated the development of local conduction delay and hence prolonged the PCL threshold of 2:2 alternans. This might be the result of increased APD heterogeneity by SKCa blockade. It has been shown that local conduction abnormality will lead to disturbance in propagation, wave breaks and reentry arrhythmia.20, 21 Similar phenomena were observed in this study. SKCa blockade promoted the atria to develop wave breaks and reentrant arrhythmia. The PCL threshold for induction of wave breaks was longer after SKCa blockade. Reentrant arrhythmia was only seen by SKCa blockade. Furthermore, failure of proper APD adaption might contribute to a substrate of arrhythmia.22 SKCa might be involved in the process of APD adaption since its blockade increased APD heterogeneity. Consequently, SKCa blockade facilitated the development of local conduction delay, wave breaks, and reentrant arrhythmia.

Conclusion

This study provides supportive evidence of GWAS studies showing association of KCNN3 and lone AF.10, 11 We show that SKCa plays a protective role against atrial arrhythmia, and SKCa blockade promotes atrial arrhythmia. Our results are in agreement with the observation that SK2 KO mice have increased AF susceptibility.13 On the other hand, Diness et al. suggested that pharmacological inhibition of SKCa prevents the onset and maintenance of AF in isolated rat and rabbit hearts. 23 Such a result is opposite to our current findings in canine atria and might be due to difference in species. Canine atrium has been considered as a good animal model for human atrial arrhythmias. However further works are required to extend the current findings to humans.

Study Limitation

We have reported distinct transmural expression of SK2 in falling human ventricles.24 It might be possible that atrium also expresses differential SK2 channels transmurally. Due to technical limitation of the optical mapping measurement, it is not feasible to perfectly match area of tissue for Western blotting and APD analysis. However, the curve fitted with SK2 does yield a statistically significant correlation. We did not systematically test the difference of APD distribution with respect to pacing site. It is unclear whether pacing the atrium at difference locations alters the APD distribution.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL78931, R01 HL78932, R01 71140 and R21 HL106554, a Piansky Endowment (M.C.F.), a Medtronic-Zipes Endowment (P.S.C.) and the Indiana University Health-Indiana University School of Medicine Strategic Research Initiative.

We thank Nicole Courtney, Jessica Warfel, Lei Lin, Jian Tan, and Janet Hutcheson for their assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Medtronic Inc, St Jude Inc, Cryocath Inc and Cyberonics Inc donated research equipment to Dr. Chen’s laboratory. Dr. Chen is a consultant to Cyberonics Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004 Aug 31;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen LY, Shen WK. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a current perspective. Heart Rhythm. 2007 Mar;4:S1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakili R, Voigt N, Kääb S, Dobrev D, Nattel S. Recent advances in the molecular pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:2955–2968. doi: 10.1172/JCI46315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia XM, Fakler B, Rivard A, et al. Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 1998 Oct 1;395:503–507. doi: 10.1038/26758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohler M, Hirschberg B, Bond CT, et al. Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science. 1996 Sep 20;273:1709–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei AD, Gutman GA, Aldrich R, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Wulff H International Union of Pharmacology. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacological reviews. 2005 Dec;57:463–472. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, Tuteja D, Zhang Z, et al. Molecular identification and functional roles of a Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel in human and mouse hearts. J Biol Chem. 2003 Dec 5;278:49085–49094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuteja D, Xu D, Timofeyev V, et al. Differential expression of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels SK1, SK2, and SK3 in mouse atrial and ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005 Dec;289:H2714–2723. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00534.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandler NJ, Greener ID, Tellez JO, et al. Molecular architecture of the human sinus node: insights into the function of the cardiac pacemaker. Circulation. 2009 Mar 31;119:1562–1575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Glazer NL, et al. Common variants in KCNN3 are associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Nature genetics. 2010 Mar;42:240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olesen MS, Jabbari J, Holst AG, et al. Screening of KCNN3 in patients with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2011 Jul;13:963–967. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozgen N, Dun W, Sosunov EA, et al. Early electrical remodeling in rabbit pulmonary vein results from trafficking of intracellular SK2 channels to membrane sites. Cardiovasc Res. 2007 Sep 1;75:758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li N, Timofeyev V, Tuteja D, et al. Ablation of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK2 channel) results in action potential prolongation in atrial myocytes and atrial fibrillation. J Physiol. 2009 Mar 1;587:1087–1100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou CC, Nihei M, Zhou S, et al. Intracellular calcium dynamics and anisotropic reentry in isolated canine pulmonary veins and left atrium. Circulation. 2005 Jun 7;111:2889–2897. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.498758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslanidi OV, Boyett MR, Dobrzynski H, Li J, Zhang H. Mechanisms of transition from normal to reentrant electrical activity in a model of rabbit atrial tissue: interaction of tissue heterogeneity and anisotropy. Biophys J. 2009 Feb;96:798–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamy C, Goodchild SJ, Weatherall KL, et al. Allosteric block of KCa2 channels by apamin. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 27;285:27067–27077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weatherall KL, Seutin V, Liegeois JF, Marrion NV. Crucial role of a shared extracellular loop in apamin sensitivity and maintenance of pore shape of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Nov 8;108:18494–18499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110724108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherry EM, Evans SJ. Properties of two human atrial cell models in tissue: restitution, memory, propagation, and reentry. Journal of theoretical biology. 2008 Oct 7;254:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenton FH, Cherry EM, Kornreich BG. Termination of equine atrial fibrillation by quinidine: an optical mapping study. Journal of veterinary cardiology: the official journal of the European Society of Veterinary Cardiology. 2008 Dec;10:87–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohara T, Qu Z, Lee MH, et al. Increased vulnerability to inducible atrial fibrillation caused by partial cellular uncoupling with heptanol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002 Sep;283:H1116–1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00927.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss JN, Qu Z, Chen PS, et al. The dynamics of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation. 2005 Aug 23;112:1232–1240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hara M, Shvilkin A, Rosen MR, Danilo P, Jr, Boyden PA. Steady-state and nonsteady-state action potentials in fibrillating canine atrium: abnormal rate adaptation and its possible mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res. 1999 May;42:455–469. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diness JG, Sorensen US, Nissen JD, et al. Inhibition of Small-Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels Terminates and Protects Against Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2010;3:380–390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.957407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang P, Turker I, Lopshire JC, et al. Heterogeneous upregulation of apamin-sensitive potassium currents in failing human ventricles. JAHA. 2012 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.004713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]