Abstract

Protein members of the AraC family of bacterial transcriptional activators have great promise as targets for the development of novel antibacterial agents. Here, we describe an in vivo high throughput screen to identify inhibitors of the AraC family activator protein RhaS. The screen used two E. coli reporter fusions; one to identify potential RhaS inhibitors, and a second to eliminate non-specific inhibitors from consideration. One compound with excellent selectivity, OSSL_051168, was chosen for further study. OSSL_051168 inhibited in vivo transcription activation by the RhaS DNA-binding domain to the same extent as the full-length protein, indicating that this domain was the target of its inhibition. Growth curves showed that OSSL_051168 did not impact bacterial cell growth at the concentrations used in this study. In vitro DNA binding assays with purified protein suggest that OSSL_051168 inhibits DNA binding by RhaS. In addition, we found that it inhibits DNA binding by a second AraC family protein, RhaR, which shares 30% amino acid identity with RhaS. OSSL_051168 did not have a significant impact on DNA binding by the non-AraC family proteins CRP and LacI, suggesting that the inhibition is likely specific for RhaS, RhaR, and possibly additional AraC family activator proteins.

Keywords: High throughput screening, Cell-based assays, AraC family activators, Antibacterial agents, Inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

The ever-growing problem of bacterial antibiotic resistance requires the identification and development of novel antibacterial agents. Traditionally, the molecular targets for antibacterial agents have been processes that are essential for bacterial growth. However, inhibition of such essential processes exerts substantial selective pressure for the emergence of resistance mechanisms that overcome the inhibition.1 One alternative strategy involves targeting virulence factors. The non-essential nature of virulence factors may reduce resistance development, but the substantial antigenic diversity they often exhibit can impede their utility as anti-microbial targets.1 Alternatively, the activator proteins that are required for the expression of bacterial virulence factors share the advantage of being non-essential, but tend to be much more conserved than virulence factors.1 Unlike the dramatic and long-term effects traditional antibiotics can have, targeting the expression of virulence factors has the potential to be considerably less disruptive to the gut microbiota. Thus, inhibitors of activator proteins that are required by bacterial pathogens for the expression of virulence factors have great potential to be developed into novel antibacterial agents.

Protein members of the large AraC family of transcriptional activators generally activate expression of genes involved in carbon metabolism, stress responses, or virulence.2 Indeed, large numbers of pathogenic bacteria, including many priority antibiotic resistant pathogens, require AraC family transcription activators for virulence factor expression and thereby to cause disease (for example,3,4). Many AraC family activators are required for the expression of multiple virulence factors; thus, blocking the function of the AraC family activator has the potential to substantially ameliorate virulence and disease. In support of this hypothesis, deletion or inhibition of many AraC family activators of virulence factor expression has been found to dramatically reduce infections (for example,5–11).

Several previously published studies have identified small molecule inhibitors of specific AraC family virulence factor regulators12–17, and in several cases, demonstrated that they can dramatically reduce infection in animal models. Among these, the hydroxybenzimidazole class of inhibitors12–14,17 has been found to inhibit seven different AraC family activators, suggesting that these inhibitors may target a relatively conserved feature of the family. These studies, together with the above evidence that deletion of AraC family activators can result in very large reductions in virulence, provide strong evidence that AraC family activators can be effective targets for novel antibacterial agents. However, it is likely that the currently available inhibitors will only be effective against a subset of the medically important AraC family activators. This is based on the family’s extremely large size and diversity – they are predicted to have arisen early in the evolution of bacteria2 and paralogs typically share only 15–30% amino acid sequence identity. Thus, screening for inhibitors of additional family members will likely identify new classes of inhibitors that inhibit additional family members.

Our study involves the AraC family activators RhaS and RhaR, which activate expression of the L-rhamnose catabolic operons in E. coli.18 RhaR activates expression of the operon that encodes RhaS and RhaR, and RhaS activates expression of the operon that encodes the L-rhamnose catabolic enzymes.18 Despite the fact that RhaS and RhaR appear to have arisen by gene duplication, and both activate transcription in response to the effector L-rhamnose, they share only 30% identity at the amino acid level.

Given that the ultimate success of developing previously identified AraC inhibitors into antibacterial agents cannot be predicted, and the fact that inhibitors have only been identified for a small fraction of the medically important family members, the goal of our study was to identify novel small molecule inhibitors of AraC family activators. We used an in vivo high-throughput screen to identify inhibitors of RhaS with the rationale that, similar to the hydroxybenzimidazole class of inhibitors, some might inhibit multiple AraC family activators. The in vivo screen circumvented the solubility problems that plague most AraC family activators, and had the further advantage that only compounds that were able to successfully enter Gram-negative bacterial cells would be identified. A secondary screen differentiated the desired RhaS inhibitors from non-specific inhibitors. The most potent of the inhibitors identified, OSSL_051168, was found to inhibit DNA binding by purified RhaS and RhaR proteins, but not by the unrelated CRP or LacI proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, growth media and growth conditions

All bacteria were strains of E. coli K-12, except strains for protein overexpression, which were strains of E. coli B (Table S1). Cultures for the primary high-throughput screen were grown in tryptone broth plus ampicillin (TB; 0.8% Difco tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, pH 7.0; all % recipes are w/v except glycerol and DMSO, which are v/v). Cultures for subsequent in vivo assays were grown in MOPS [3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid]-buffered minimal medium as previously described.18 Cultures for phage P1vir infection were grown in tryptone-yeast extract broth (TY; 0.8% Difco tryptone, 0.5% Difco yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, pH 7.0) supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2. Difco Nutrient Agar was used routinely to grow cells on solid medium. Difco MacConkey Base Agar supplemented with 1% sorbitol or maltose was used to screen for sorbitol- and maltose-deficient phenotypes. Ampicillin (200 µg/mL), tetracycline (20 µg/mL), chloramphenicol (30 µg/mL), gentamycin (20 µg/mL), L rhamnose (0.2%), glucose (0.2%), and isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.1 mM unless otherwise noted) were added as indicated. All cultures were grown at 37°C with aeration, unless otherwise noted.

High-throughput screening compound library

High-throughput screening was performed using the compound library at the University of Kansas High Throughput Screening Laboratory, which consisted of approximately 100,000 compounds. Compounds were purchased from ChemBridge Corp. (San Diego, CA), Chemdiv, Inc. (San Diego, CA), Prestwick Chemicals (Illkirch, France) and MicroSource Discovery Systems, Inc. (Gaylordsville, CT). Compounds were selected based on structural diversity and drug-like properties.

Primary high-throughput screen

An overnight culture of E. coli strain SME3006 (Table S1) grown in TB with ampicillin was diluted 1:100 into fresh TB with ampicillin that had been pre-warmed to 37°C. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.1 and growth was stopped on ice for approximately 30 min. Using a Multidrop 384 (Thermo Scientific, Hudson, NH), 35 µL of this cell culture was added to each well of a 384-well plate (Nunc, Rochester, NY). In addition to cells, each well in column 1 of the plate contained 20 µL 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 10 µL water (uninduced control); each well in column 2 contained 20 µL 2.5% DMSO and 10 µL 2% L rhamnose (induced control); and each well in columns 3–24 contained 20 µL of a library compound at 25 µg/mL in 2.5% DMSO and 10 µL 2% L rhamnose. Plates were incubated statically for 3 h at room temperature to allow rhaB-lacZ induction, followed by addition of 25 µL lysis/ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) buffer [3 parts ZOB19 to 1 part 10 mg/mL lysozyme (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in PopCulture cell lysis reagent (EMD Chemicals, Inc., Gibbstown, NJ)]. After approximately 3 h of incubation at room temperature, OD405 readings were taken for each well using an EnVision Multilabel Reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The average of the 16 induced and 16 uninduced wells on each individual plate were used to calculate the percent activation for each well as follows:

Z-factors were calculated as in Zhang et al.20 for each individual 384-well plate screened.

HTS strain construction

The tester strain for the primary high-throughput screen was SME3006. This strain carried the RhaS-activated Φ(rhaB-lacZ)Δ84 fusion18 in single copy on the chromosome. The rhaBAD promoter in this fusion includes the full binding site for the RhaS protein, but not the upstream binding site for CRP. This ensures that RhaS is the sole activator of this fusion, and that inhibition of CRP protein activity would not decrease LacZ expression. This strain also carries ΔrhaS and recA::cat on the chromosome and RhaS expressed from plasmid pHG165rhaS18, which modestly increases rhaB-lacZ expression levels compared with chromosomal rhaS expression.

The control strain for the secondary high-throughput screen and subsequent experiments was SME3359 (Table S1), and carries the LacI-repressed fusion and LacI-expressing pHG165lacI. The fusion consists of lacZ under the control of an artificial promoter (Phts) with an induced expression level similar to that of the induced rhaBAD operon. Phts is regulated by LacI and induced with IPTG. The Phts core promoter elements include a near-consensus -35 sequence (5’-TTGACT-3’) and a -10 sequence (5’-TACTAT-3’) followed by a lacO1 operator sequence that overlaps the transcription start site with the same spacing as lacO1 at lacZYA. To construct the upstream half of Phts, oligo 2829 (5’-CGAgaattcATTTTAGGCACCCCAGGCTTGACT-3’) was annealed to oligo 2788 (5’-CTAGAActcttcGTAGAGCCGGAAGCATAAAGAGTCAAGCCTGGGGTGCCTAAAAT-3’) and the primers were extended using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). (The complementary sequences in the oligos are underlined; restriction endonuclease recognition sites are in lower case.) The downstream half of the Phts promoter was constructed by similarly annealing and extending oligos 2789 (5’-CTAGAActcttcACTACTATGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGC-3’) and 2790 (5’- CTAggatccTTCATAGCTGTTTCCTGTGTGAAATTGTTATCG-3’). The PCR products were cleaned up with a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA), digested with EarI, EcoRI, and BamHI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), and then ligated to EcoRI- and BamHI-digested pRS414 (Table S1). The sequence of both DNA strands of the cloned region was confirmed (Northwestern University Genomics Core, Chicago, IL). Phts-lacZ was recombined onto λRS45 and integrated as a single-copy lysogen21 into the chromosome of strain SME1085. Likely single-copy lysogens were identified by β galactosidase assay18 and confirmed by PCR22. The resulting strain was transformed with LacI-expressing pHG165lacI.

Secondary high-throughput screen

We re-screened the top ~5% most inhibitory compounds from the primary screen. The secondary screen was performed essentially as the primary screen, except for the following changes: Cells were grown in MOPS-buffered minimal medium with ampicillin rather than TB with ampicillin. Compounds were tested against both SME3006 and SME3359. For plates containing SME3359, 6.5 mM IPTG was used as the inducer rather than 2% L rhamnose, and the first and second columns were uninduced and induced controls, analogous to above.

Strain construction for in vivo dose-response studies

For dose-response studies, a rhaB-lacZ reporter strain was designed that allowed IPTG induction of RhaS or RhaS(163–278) expression from pHG165 (and thus rhaB-lacZ expression). The strain was constructed by introducing malP::lacIq from strain SG22166 into SME3000 via phage P1vir-mediated generalized transduction, by the previous method.23 The resulting strain, SME3000 malP::lacIq zhc-511::Tn10, was transduced with recA::cat from SME1048 by selecting for chloramphenicol resistance, to make strain SME3632.

In vivo Dose-response experiments

The top hit identified in the screen was 1-ethyl-4-nitromethyl-3-quinolin-2-yl-4H-quinoline. The closely related compound, OSSL_051168, 1-butyl-4-nitromethyl-3-quinolin-2-yl-4H-quinoline, was obtained from eMolecules, Inc. (Solana Beach, CA; catalog #3761-0013) or Princeton BioMolecular Research (Princeton, NJ; catalog #OSSL_051168), with the Princeton named used here. OSSL_051168 was dissolved in 100% DMSO and then the solution was further diluted in 100% DMSO in a 2-fold series for a total of seven concentrations. Dose-response assays were performed in 96-well plates with one column each of uninduced and induced controls for each strain, and one column with a concentration curve of OSSL_051168 for each strain. Uninduced wells contained 20 µL water and 40 µL 10% DMSO; induced wells contained 20 µL induction solution (2% L rhamnose and 6.5 mM IPTG) and 40 µL 10% DMSO; concentration curve wells contained 20 µL induction solution, 36 µL water and 4 µL diluted OSSL_051168. The appropriate cell culture (70 µL, grown to OD600 = 0.1 in MOPS-buffered minimal medium with ampicillin) was added to each well and induced for 3 h at 37°C. Lysis/ONPG buffer (50 µL, as in Primary Screen) was added to each well and the plate was immediately placed into a PowerWave XS plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT), set to read the OD420 of each well every 15 min for 4 h. A single time point within the linear range of β-galactosidase activity was chosen for analysis for each strain. Due to differences in kinetics of lacZ reporter expression, the rhaB-lacZ strains were analyzed at 4 hours and the hts-lacZ strain was analyzed at 1 h. Percent activity was calculated for each condition as described above, using the single time point with appropriate OD420 levels for each strain. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. IC50 and maximal inhibition values were calculated using the XLfit add-in for Microsoft Excel (ID Business Solutions, Guildford, UK), and graphs were drawn using Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Growth Curves

Strains SME3634 and SME3359 were grown overnight (~16 h) at 37 °C in MOPS-buffered minimal medium.18 Overnight grown cultures were diluted into the same medium plus rhamnose to an O.D600 of 0.1, and IPTG was added. 1 mL aliquots of the cultures were added to wells of a 24-well plate, with the addition of either 44 µM OSSL_051168 (dissolved in 100% DMSO) or an equal volume of 100% DMSO. Growth was monitored at 20 min intervals for approximately 8 h at 37 °C with continuous shaking in a PowerWave XS plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Protein purification

All proteins for this study were expressed in E. coli. Untagged CRP was purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography as described.24 LacI protein was purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and phosphocellulose column chromatography as described.25 RhaS-GB1201b and GB1b-RhaR were purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography. Briefly, plasmids derived from pET21 and expressing RhaS-GB1201b and GB1b-RhaR were transformed into competent cells of strains Acella™ (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany) or ArcticExpress(DE3) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA), respectively. The cells were grown in 1 liter TY plus ampicillin and rhamnose. Gentamycin was also added for GB1b-RhaR. The cells were grown to OD600 of 0.5, transferred to a 15 °C shaker, 0.1 mM IPTG was added, and then incubated overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in 30 mL of cold binding buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 7.9) plus L-rhamnose. Cells were lysed by three cycles of freeze thaw [with addition of lysozyme (0.4 mg/mL), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP, 1 mM) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, 1 mM), at −80 °C] followed by sonication, and then centrifuged to remove cell debris. The supernatant was applied using an AKTAexplorer FPLC (GE Healthcare) to a 5 mL HiTrap Chelating HP column (GE Healthcare) that had been charged with 50 mM NiSO4, and equilibrated with 15 mL H20 and then 15 mL binding buffer. After loading, the column was washed with 25 mL binding buffer, then 25 mL wash buffer (binding buffer, but with 60 mM imidazole) plus L-rhamnose. A 10 mL gradient of binding buffer with 60 mM to 250 mM imidazole was run and then 15 mL of elution buffer (binding buffer, but with 250 mM imidazole). The ArcticExpress cold-adapted chaperonins Cpn10 and Cpn60 (14 monomers per unit) co-purified with GB1b-RhaR, thus GB1b-RhaR represented only approximately 20% of the total protein used in the assays.

In vitro DNA binding assays

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed as described26, with the following modifications. Reaction volumes were 12 µL total (with 5 µL loaded in each lane), in 1x EMSA buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM KEDTA, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10 µg salmon sperm DNA]. Reactions also contained additives as follows: RhaS-GB1201b, L-rhamnose; GB1b-RhaR, Nonidet P40 and L-rhamnose; CRP, cAMP; LacI, none. Purified proteins were buffer exchanged into 1x EMSA buffer minus BSA and salmon sperm DNA, and without the addition of additives. Electrophoresis was performed in 0.25× TBE (final concentrations: 22.25 mM Tris base, 22.25 mM boric acid, 500 µM disodium EDTA, pH 8.3). All EMSA reactions, including those without inhibitor, had a final concentration of 10% DMSO (OSSL_051168 solvent). DNA probes were generated by hybridizing the following oligonucleotides (oligos): For RhaS-GB1201b, oligo 3058 (5’-[IRD700]ACGTTCATCTTTCCCTGGTTGCCAATGGCCCATTTTCCTGTCAGTAACGAGAAGGTCGCGAA-3’) and oligo 3288 (5’-TTCGCGACCTTCTCGTTACTGACAGGAAAATGGGCCATTGGCAACCAGGGAAAGATGAACGT-3’); for GB1b-RhaR, oligo 3056 (5’-[IRD700] CGCTGTATCTTGAAAAATCGACGTTTTTTACGTGGTTTTCCGTCGAAAATTTAAGGTAAGAAC-3’) and oligo 3287 (5’- GTTCTTACCTTAAATTTTCGACGGAAAACCACGTAAAAAACGTCGATTTTTCAAGATACAGCG-3’); for CRP, oligo 3161 (5’-[DY682] CACAATTCAGCAAATTGTGAACATCATCACATTCATCTTTCCCTG-3’) and oligo 3162 (5’-[DY682] CAGGGAAAGATGAATGTGATGATGTTCACAATTTGCTGAATTGTG-3’); and for LacI, oligo IR O1-For (5’-[IRD700] TGTTGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG-3’) and oligo O1-Rev (5’-CCTGTGTGAAATTGTTATCCGCTCACAATTCCACACAACA3’). IRD700- and DY682-labeled oligos were from Eurofins MWG Operon. For each oligo pair, 100 µmol of each oligo was combined and the reaction was diluted in STE buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) to 20 µL, heated to 94°C for 2 min, and cooled to room temperature. The double-stranded DNA probes were further diluted in STE, and 0.3–1 µL added to EMSA reactions. To ensure that protein was limiting in the reactions, protein concentrations were adjusted so that less than 100% of the total DNA was bound in the absence of inhibitor (55–85% bound DNA among the replicates for all of the proteins assayed). EMSA gels were imaged using an Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE), and quantified using the Odyssey software, version 3.0.30. The quantity of DNA bound with 10 µM inhibitor was approximately equal to the bound DNA in the absence of inhibitor and was set to 100% for RhaS-GB1201b, GB1b-RhaR, and LacI. For CRP, the quantity of DNA bound in the absence of inhibitor was set to 100%. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Inhibition values were calculated and graphs were drawn as for in vivo dose-response experiments.

RESULTS

High-throughput screen to identify inhibitors of AraC family activators

Our goal was to use high throughput screening to identify novel inhibitors that could block the function of AraC family activator proteins. Ultimately, such inhibitors have the potential to be developed into antibacterial agents that block virulence factor expression in human pathogens. Although it does not regulate virulence factor expression in any human pathogens, we chose the RhaS protein as our initial target since the molecular mechanisms used by RhaS to activate transcription are well characterized (for example18,26).

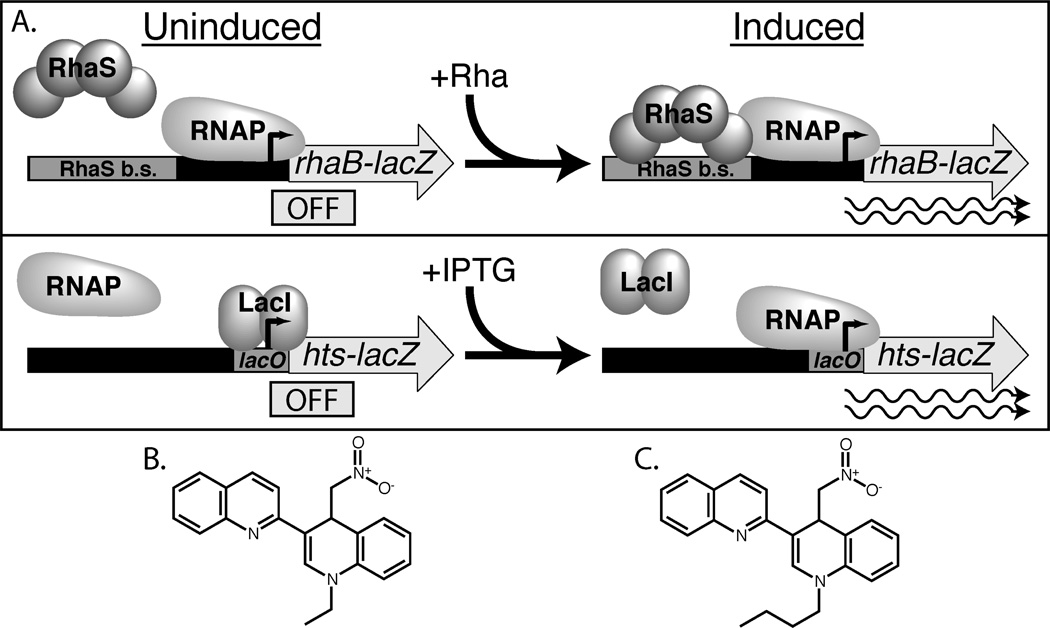

The first step of our in vivo high-throughput screen for RhaS inhibitors was to screen for compounds that decreased expression of a RhaS-activated rhaB-lacZ reporter fusion in whole cells (Fig. 1A, top). Screening in whole cells (rather than with purified protein) was advantageous for two reasons. First, RhaS is very insoluble, and purified, active RhaS protein was not available at the time of this screen. Second, whole-cell screens are expected to identify only compounds that can enter, and remain active in the bacterial cell. The disadvantage of our whole-cell assay was that many compounds were expected to affect RhaS-activated LacZ reporter activity without directly affecting activation by RhaS. In order to screen out the vast majority of such indirect effects, each compound that reduced the RhaS-activated LacZ reporter activity in the primary screen was re-tested, both on the primary screening strain and on a secondary screening strain. The secondary screening strain was an isogenic control strain carrying a lacZ reporter fusion (hts-lacZ), with a synthetic promoter that was repressed by LacI, and did not require RhaS for activation (Fig. 1A, bottom). Non-specific inhibitors that blocked β-galactosidase enzyme activity or cell growth, for example, were expected to decrease lacZ expression from both rhaB-lacZ and hts-lacZ. In contrast, the compounds of interest that specifically inhibited RhaS were expected to decrease lacZ expression from rhaB-lacZ (primary screen), but not from hts-lacZ (secondary screen).

Figure 1.

Reporter fusions used in high-throughput screen and structure of OSSL_051168 compared with compound identified in the screen. (A) Top: Primary screen, RhaS-activated rhaB-lacZ fusion, shown in uninduced, (−)rhamnose state (left) and induced (+)rhamnose state (right). Bottom: Secondary screen, LacI-repressed hts-lacZ control fusion, shown in uninduced, (−)IPTG state (left) and induced (+)IPTG state (right). Gray rectangles: RhaS and LacI (lacO) binding sites. Gray arrows: lacZ gene expressed from rhaBAD or synthetic hts promoter. Thick black/gray line: Promoter region DNA. Right angle black arrow: transcription start sites. Rounded gray shapes: RNAP, RhaS or LacI proteins. Wavy lines: active transcription in the presence of inducers L-rhamnose (Rha) and IPTG. (B) The hit from the high throughput screen, 1-ethyl-4-nitromethyl-3-quinolin-2-yl-4H-quinoline. (C) OSSL_051168, 1-butyl-4-nitromethyl-3-quinolin-2-yl-4H-quinoline.

We screened a library of ~100,000 small-molecule compounds for those that decreased rhaB-lacZ expression in the primary screening strain using a high-throughput β-galactosidase assay (modified from19). All but three of the 295 plates (384-well) assayed had Z-factors of 0.5 or above, and the remaining three plates had Z-factors above 0.4. (The Z’ scores in the 0.4 range could be traced to one or two positive or negative control wells on each plate with somewhat aberrant signals). The average of the Z-factors for all of the plates was 0.7, indicating that this was an excellent assay20. A major contribution to the performance of the assay was that the positive and negative controls had coefficients of variation of only 2–3% over the entire assay.

The inducer for RhaS activation of rhaBAD transcription, L-rhamnose, was added to the assay wells at the same time as the compounds. In this way, rhaB-lacZ expression was uninduced until exposure to the compounds, and it wasn’t necessary for pre-formed β-galactosidase to decay before inhibition could be detected. We further studied compounds that resulted in rhaB-lacZ expression levels that were at least three standard deviations below the mean of all of the compounds in the study. This allowed us to focus further efforts on a convenient number of compounds likely to show significant inhibition. These compounds decreased rhaB-lacZ expression levels to between zero and seventy-five percent of the fully induced, non-inhibited control expression levels (data not shown).

The ~300 most inhibitory compounds from the primary screen (~0.3% hit rate) were re-assayed with both the RhaS-activated rhaB-lacZ fusion and the LacI-repressed control hts-lacZ fusion (data not shown). IPTG, the inducer of the LacI-repressed hts-lacZ fusion, was added to the assay wells at the same time as the compounds. Similar to addition of the inducer L-rhamnose to the primary screen, this resulted in LacZ expression that was uninduced until exposure to compounds. We ranked each compound by the difference in lacZ expression levels between the RhaS-activated and the LacI-repressed fusions. Expression levels were normalized to the average of the uninduced controls (set to 0%) and the average of the induced controls (set to 100%). The data were plotted as a scatter plot of the RhaS-activated (x-axis) versus LacI-repressed (y-axis) expression levels. Compounds that inhibited expression from the RhaS-activated fusion to a greater extent than the LacI-repressed fusion (upper left quadrant of plot) were likely specific inhibitors of RhaS activity, and were of further interest. We selected the 16 compounds that best fit these criteria for further study as potential specific RhaS inhibitors. These compounds exhibited considerable structural diversity.

Dose-dependent inhibition of RhaS

We tested the effects of various concentrations of the 16 potential RhaS inhibitors on activation of the RhaS-activated fusion compared with the LacI-repressed fusion to identify those with dose-dependent inhibition (data not shown). The set of hits displayed considerable structural diversity, including various heterocyclic ring systems having a range of drug-like properties. One of the compounds showed particularly robust, dose-dependent inhibition of the RhaS-activated fusion, and substantially less inhibition of the LacI-repressed fusion. In addition, its structure was viewed as amenable for potential medicinal chemistry optimization. We further describe studies of OSSL_051168, which is nearly identical in structure to the compound identified in the screen, was readily available commercially, and inhibited to the same extent as the screen compound (data not shown) (Fig. 1B & C). We found that OSSL_051168 inhibited expression of the RhaS-activated rhaB-lacZ fusion to a much greater extent than the LacI-repressed hts-lacZ fusion (Fig. 2, circle and square markers). OSSL_051168 was able to fully inhibit expression of the RhaS-activated fusion, and had an IC50 value of approximately 30 µM. Although there was a small amount of non-specific inhibition, the majority of the OSSL_051168 inhibition appears to be specific for RhaS. OSSL_051168 is not structurally related to any of the inhibitors of AraC family activators that have been previously identified12–17.

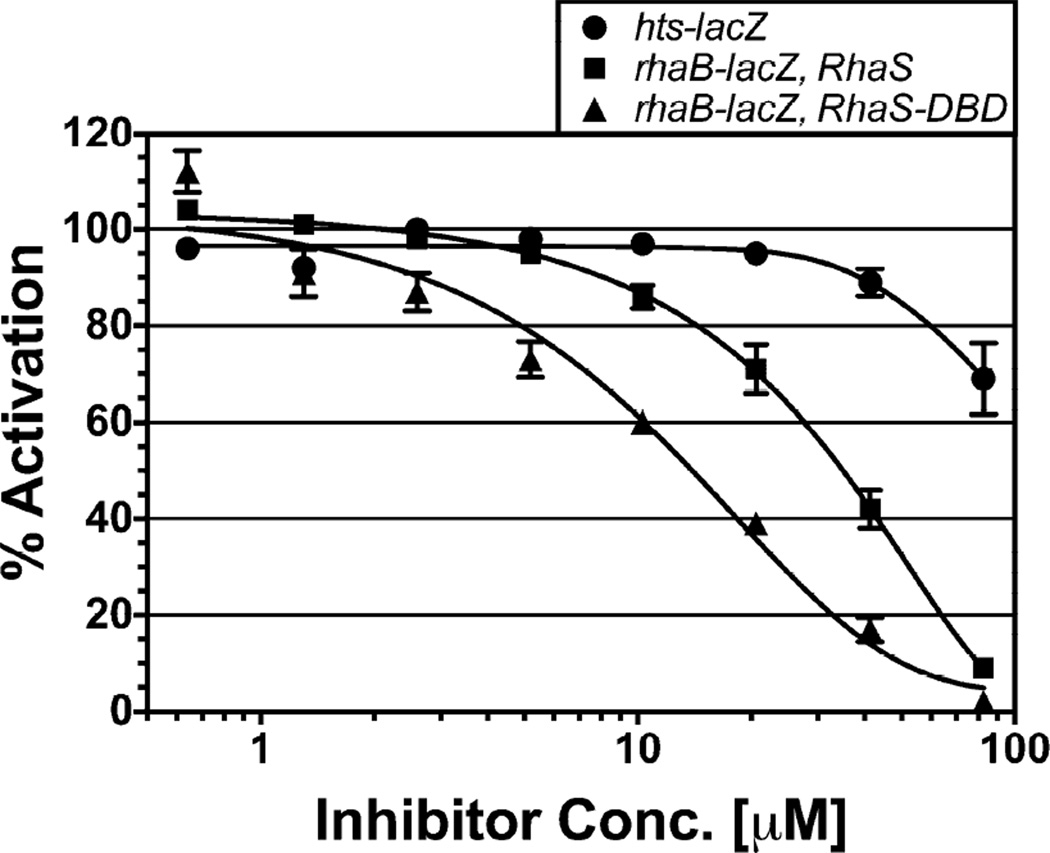

Figure 2.

In vivo effects of OSSL_051168 on β-galactosidase expression from the reporter fusions hts-lacZ (SME3359, circles) and rhaB-lacZ activated by full-length RhaS (SME3634, squares) or RhaS(163–278) (RhaS-DBD, SME3635, triangles). Activity in the absence of inhibitor was set to 100% for each reporter fusion. Results are the average of three independent experiments with two replicates each.

OSSL_051168 inhibited the RhaS DNA-binding domain to the same extent as full-length RhaS

The first step we took toward identifying the mechanism of RhaS inhibition by OSSL_051168 was to determine whether the RhaS N-terminal domain was required for the inhibitory effect. Proteins are defined as AraC family members if they contain a conserved DNA binding domain that includes two helix-turn-helix motifs, as defined by Prosite entry PS01124 (prosite.expasy.org/PS01124).2 The RhaS C-terminal DNA-binding domain alone [residues 163 to 278, RhaS(163–278), previously published as RhaS-CTD] is capable of activating transcription of the rhaB-lacZ fusion used in these studies, albeit to approximately a three-fold lower level than full-length RhaS.27 We therefore compared the effect of OSSL_051168 on activation of the RhaS-activated rhaB-lacZ fusion by full-length RhaS and RhaS(163–278) (Fig. 2). We found that OSSL_051168 inhibited RhaS(163–278) to at least the same extent as full-length RhaS. OSSL_051168 was again able to fully inhibit expression, this time with an IC50 value of approximately 10 µM. This result indicates that the RhaS N-terminal domain, which is required for dimerization and L-rhamnose binding, is not required for OSSL_051168 inhibition of RhaS. We therefore conclude that OSSL_051168 specifically inhibits a function of the RhaS DNA-binding domain: likely DNA binding or contacts with the RNA polymerase σ subunit.

OSSL_051168 does not inhibit cell growth

All of our assays to this point were performed in whole cells, thus it was important to test whether OSSL_051168 had any significant effects on the growth of the bacterial cells. We assayed the growth of the strains carrying the RhaS-activated and the LacI-repressed fusions, grown in the same minimal medium used for the in vivo dose response assays. We found that there was no impact of the inhibitor on the growth of the cells for either strain (Fig. S1). There was a very slight divergence of the plus and minus inhibitor curves at the end of the growth period, however this was not due to inhibitor toxicity, since the cells grown without inhibitor had the slower growth. This result supports the hypothesis that the inhibition we observed in the in vivo assays was likely due to specific inhibition of RhaS activation.

OSSL_051168 inhibits in vitro DNA binding by RhaS and RhaR

In order to perform in vitro DNA binding assays with RhaS, we needed purified protein that was soluble and active. With the exception of low levels of activity from denatured and subsequently refolded protein28, we have not previously been able to observe in vitro DNA binding by full-length RhaS, apparently due to its extremely low solubility. Two modifications were required to obtain soluble and active RhaS for these studies. First, we used a RhaS variant, RhaS L201R18, which binds DNA more strongly than wild-type RhaS. The second modification was to fuse a GB1basic solubility-enhancement tag29 to the C-terminus of full-length RhaS L201R, yielding RhaS L201R-GB1basic (referred to as RhaS-GB1201b for brevity). The “basic” variant of GB1 was necessary to prevent tight binding between RhaS and GB1 that blocked DNA binding (Skredenske, Deng and Egan, unpublished). RhaS-GB1201b is soluble and binds DNA in vitro, with increased DNA binding in the presence of L-rhamnose (Deng and Egan, unpublished), as expected for functional RhaS based on previous studies28.

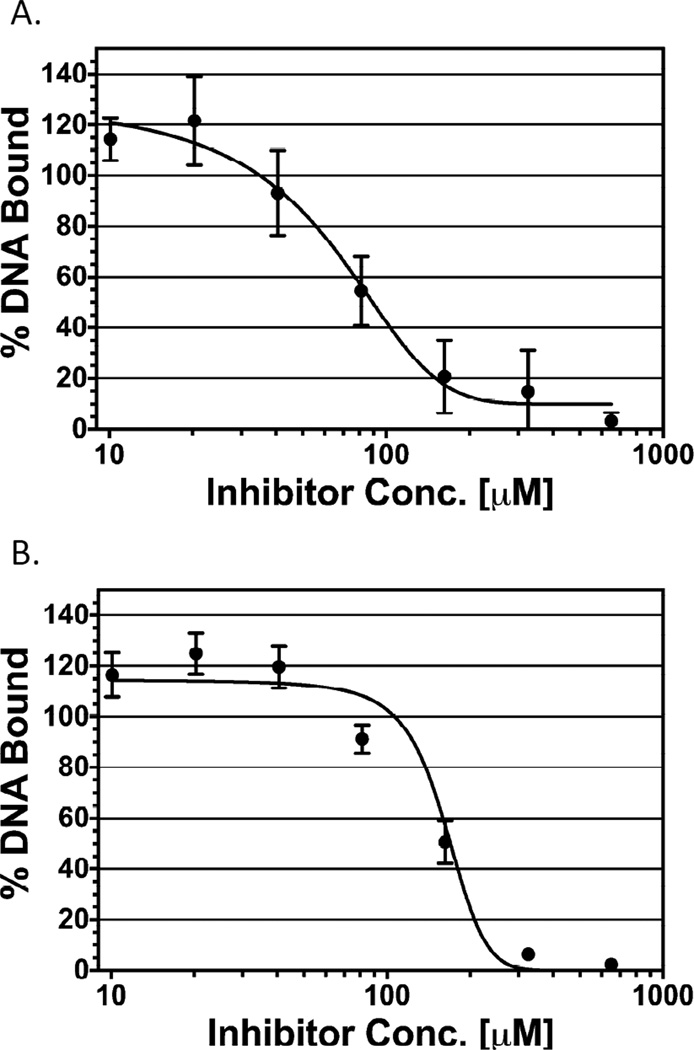

We used the electrophoretic mobility shift assay [EMSA] to investigate whether OSSL_051168 inhibited in vitro DNA binding by RhaS-GB1201b. We incubated RhaS-GB1201b with dsDNA containing the RhaS binding site sequence from the rhaBAD promoter region (this includes binding sites for both monomers of the RhaS-GB1201b dimer) in the absence or presence of various concentrations of OSSL_051168. We found that OSSL_051168 was able to fully inhibit DNA binding by RhaS-GB1201b in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). We calculated an IC50 of approximately 70 µM, which is in reasonable agreement with the 30 µM IC50 calculated from the in vivo assays of RhaS inhibition, especially considering the many experimental differences. From this result, we conclude that the inhibition of RhaS activity observed in in vivo assays was likely due to OSSL_051168 blocking the ability of RhaS to bind to DNA.

Figure 3.

Effect of OSSL_051168 on DNA binding by RhaS-GB1201b and GB1b-RhaR. The DNA bound (assayed by EMSA) at the lowest concentration of inhibitor (OSSL_051168) was set to 100%, and binding in all other cases is represented relative to that value. Inhibitor concentrations ranged from 10 to 650 µM, with serial two-fold dilutions. Results are the average of three independent experiments. (A) RhaS-GB1201b. Final concentrations of DNA and protein were 2.5 nM and 2.4 µM, respectively. (B) GB1b-RhaR. Final concentrations of DNA and protein were 1.3 nM and 2.2 µM, respectively.

We also tested the ability of OSSL_051168 to inhibit DNA binding by the RhaR protein. As mentioned above, although RhaS and RhaR both activate transcription in response to the effector L-rhamnose, they are only 30% identical to each other. The identity in their DNA binding domains is approximately the same, at 34% amino acid identity. E. coli AraC family activators have pairwise amino acid identities that range from single digits to 56%, thus RhaS and RhaR share an intermediate level of identity

We purified RhaR as a fusion protein with GB1basic, GB1b-RhaR, which resulted in soluble protein that was active for DNA binding – showing the expected increase in DNA binding in the presence of L-rhamnose (Deng and Egan, unpublished). We found that OSSL_051168 inhibited DNA binding by purified GB1b-RhaR protein to approximately the same extent as RhaS-GB1201b protein (Fig. 3B). OSSL_051168 was able to fully inhibit GB1b-RhaR binding to DNA, with an IC50 value of approximately 140 µM. The Hill coefficients for the in vivo and in vitro assays of dimeric RhaS and RhaR were all approximately two [in contrast to the Hill coefficient of approximately one for monomeric RhaS(163–278)] (data not shown), suggesting possible positive cooperativity for inhibitor binding by full-length dimeric RhaS and RhaR proteins.

OSSL_051168 does not inhibit DNA binding by non-AraC family proteins

Our results indicated that OSSL_051168 inhibits DNA binding by both the RhaS and RhaR proteins. We used two unrelated proteins, the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) and the Lac repressor protein (LacI), to test whether OSSL_051168 was specific for inhibition of RhaS and RhaR (and perhaps other AraC family proteins), or was broadly inhibitory toward DNA binding proteins. CRP and LacI each share only 10–12% sequence identity with RhaS and RhaR. Neither CRP nor LacI contains the two helix-turn-helix motifs (per monomer) that is characteristic of AraC family proteins2. Broad inhibition of DNA binding by OSSL_051168 would be expected to have a major impact on cell growth; therefore, the finding that OSSL_051168 had minimal impact on growth of the strains used for our in vivo studies (Fig. S1) was the first evidence that broad inhibition was unlikely.

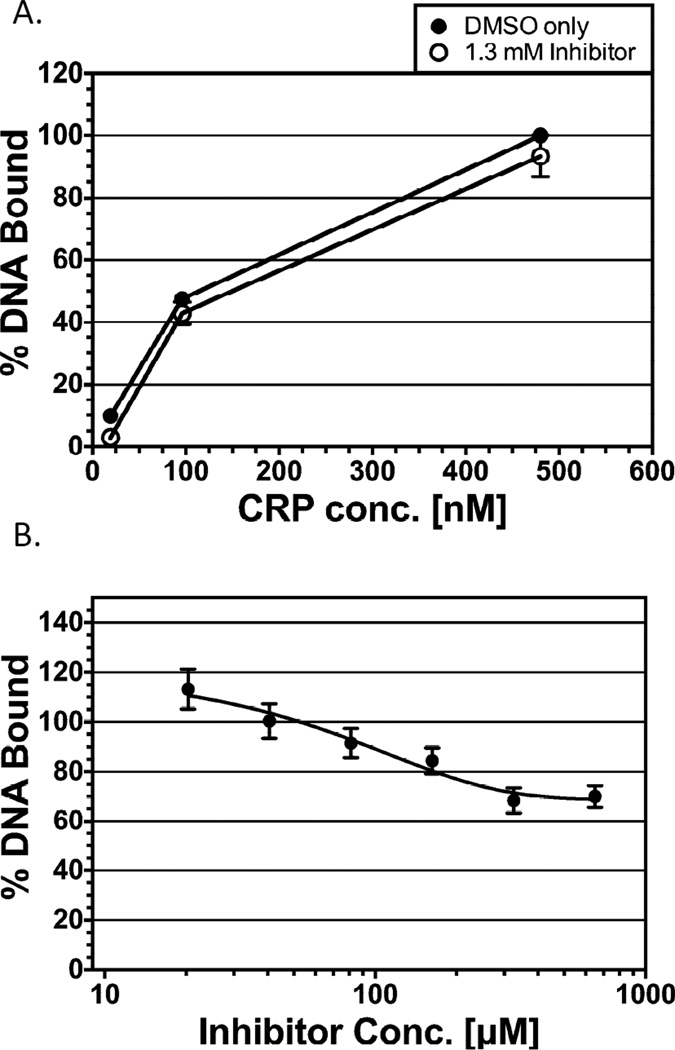

We first tested the effect of OSSL_051168 on DNA binding by CRP. EMSA reactions were performed with varying concentrations of purified CRP protein. The OSSL_051168 concentration (1.3 mM) was two-times higher than the concentration required in in vitro assays to nearly eliminate RhaS binding to DNA. We found that even at this very high concentration of OSSL_051168, approximately 94% of the CRP DNA binding was retained (Fig. 4A). Thus, OSSL_051168 resulted in only a very slight inhibitory effect on DNA binding by CRP.

Figure 4.

Effect of OSSL_051168 on DNA binding by non-AraC family activators. DNA binding was assayed by EMSA. (A) CRP; at 480, 96 and 19 nM. DNA bound at 480 nM CRP in the absence of inhibitor was set to 100%, and all other values are represented relative to that value. OSSL_051168 was added at 1.3 mM where indicated. Final concentration of DNA was 0.84 nM. Results are the average of two independent experiments. (B) LacI; the DNA bound at the lowest concentration of inhibitor (OSSL_051168) was set to 100%, and binding in all other cases is represented relative to that value. Inhibitor concentrations ranged from 20 to 650 µM, with serial two-fold dilutions. Results are the average of three independent experiments. Final concentrations of DNA and protein were 90 nM and 5.6 µM, respectively.

As a second test of whether OSSL_051168 inhibition is specific for AraC family activators, we tested the lac repressor protein, LacI (Fig. 4B). EMSA assays were again performed; in this case various dilutions of OSSL_051168 (starting at 650 µM) were added to reactions with LacI protein at a concentration just sufficient to shift nearly the entire DNA band. The highest concentrations of OSSL_051168 had only a slight effect on LacI DNA binding, with approximately 70% of DNA binding retained. Note that this in vitro test of LacI binding to DNA was not redundant with the in vivo hts-lacZ reporter assay, since LacI was in its induced state in the reporter assay, and therefore not bound to DNA.

Taken together, the CRP and LacI results indicate that OSSL_051168 doesn’t simply inhibit the activity of all DNA binding proteins, and further that not all helix-turn-helix containing proteins are inhibited. It has yet to be determined whether OSSL_051168 is specific for only RhaS and RhaR. However, the above finding that OSSL_051168 inhibits RhaR, a protein with only 30% identity with RhaS, suggests the possibility that OSSL_051168 might inhibit DNA binding by additional AraC family proteins, perhaps including activators of virulence factor expression in bacterial pathogens.

DISCUSSION

Screen Identified Inhibitors of AraC Family Activators

Members of the AraC family of transcriptional activators have excellent potential as targets for novel antibacterial agents based on the fact that they are required for the expression of virulence factors in many bacterial pathogens (for example,5–11). These include many bacteria that pose serious human health threats due to their resistance to currently available antibiotics. Thus, there is an urgent need for novel antibacterial agents. The goal of this study was to screen for and begin to characterize small molecule inhibitors of AraC family transcriptional activators. Such inhibitors will be useful in the study of bacterial pathogenesis, and have the potential to be developed into novel antibacterial agents. Although several previous inhibitors of AraC family activators have been identified12–17, the diversity of proteins in the family indicates the likelihood that the current inhibitors will only be effective against a subset of family members.

We developed and validated a novel high throughput assay to screen for small molecule inhibitors of the E. coli AraC family activator protein RhaS. The in vivo assay achieved specificity for RhaS inhibitors through comparison of expression levels from two reporter constructs; one that was transcriptionally activated by RhaS, and a second that was transcriptionally repressed by the non-AraC family repressor LacI. The LacI-repressed reporter enabled us to identify and eliminate non-specific inhibitors from consideration. Of the compounds identified in our screen, we further investigated one compound, OSSL_051168, which was an especially effective inhibitor of RhaS. OSSL_051168 is not structurally related to any of the previously identified small molecule inhibitors of AraC family activators, and thus is a novel inhibitor.

Specificity and Potency of OSSL_051168

Given that OSSL_051168 was identified through a whole-cell high throughput screen, and has not undergone chemical optimization, its potency is very reasonable. The following results indicate that the majority of the OSSL_051168 inhibition that we observed in whole cell assays was specific for AraC family proteins. First, we found very little inhibition of expression from the control fusion, hts-lacZ, indicating that there wasn’t significant inhibition of β-galactosidase enzyme activity or of any processes that impacted transcription or growth rate. The absence of an impact of OSSL_051168 on E. coli growth rate was more directly confirmed by comparing cell growth rates in the absence and presence of OSSL_051168. Finally, we determined that OSSL_051168 had only very little effect on DNA binding by two proteins unrelated to the AraC family and unrelated to each other, CRP and LacI. This result suggests that OSSL_051168 does not inhibit by a non-specific mechanism such as binding to DNA to block protein binding. Since both CRP and LacI use helix-turn-helix motifs to contact DNA, this finding also suggests that OSSL_051168 doesn’t generally block DNA binding by helix-turn-helix containing proteins. Therefore, it appears that inhibition by OSSL_051168 involves binding to some feature that is unique to RhaS, RhaR, and possibly additional AraC family activator proteins.

Mechanism of Action: OSSL_051168 Inhibits the Conserved AraC Family DNA Binding Domain

In addition to their conserved DNA binding domains, the majority of AraC family proteins contain a second, non-conserved, domain that regulates the activity of the DNA binding domain, and in some cases imparts dimerization.2

The mechanism of action has been published for several previously identified AraC family small molecule inhibitors. The first was Virstatin, which inhibits dimerization by binding to the ToxT effector-binding pocket in the non-conserved domain and mimicking negative regulators of ToxT activity, such as palmitoleic acid.30 The finding that Virstatin targets the non-conserved AraC family protein domain suggests that it is likely to inhibit a relatively narrow set of AraC family activators. (There are advantages and disadvantages to both narrow and broad-spectrum antibacterial agents.) In contrast, the hydroxybenzimidazole class of inhibitors targets a number of different AraC family proteins.12–14,17 Several compounds in this class of inhibitors have been shown to block DNA binding.12–14,17 Overall, the data from these publications supports a model in which the hydroxybenzimidazole class of inhibitors targets the AraC family DNA binding domain.

Given the uncertainties inherent in the development of compounds into drugs, and the enormous diversity of AraC family proteins, we screened for additional inhibitors of AraC family activators, specifically the E. coli RhaS protein. We identified OSSL_051168, which is a novel inhibitor of AraC family activators that is not structurally related to the previously identified inhibitors. Our findings indicate that OSSL_051168 inhibits the activity of the more conserved of the two RhaS domains, the DNA binding domain. Thus, OSSL_051168 might inhibit the activity of additional AraC family proteins; and indeed, we found that OSSL_051168 also inhibited DNA binding by RhaR. Taken together, our results lead to the hypothesis that the OSSL_051168 mechanism of action involves binding to the DNA binding domain of AraC family proteins and blocking their ability to bind to DNA (Fig. S2).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful for the assistance of members of the KU High Throughput Screening Laboratory, especially Rathnam Chaguturu, Veena Vasandani and Ashleigh Price. We also thank Liskin Swint-Kruse, University of Kansas Medical Center, for generous gifts of pHG165lacI, purified LacI protein, and oligonucleotides O1-For and O1-Rev. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM55099. JMS was partially supported by award number T32GM008359. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:117–128. doi: 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallegos MT, Schleif R, Bairoch A, Hofmann K, Ramos JL. AraC/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:393–410. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.393-410.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis MS, Wolf-Watz H, Forsberg A. Regulation of type III secretion systems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:166–172. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J, Tauschek M, Robins-Browne RM. Control of bacterial virulence by AraC-like regulators that respond to chemical signals. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casaz P, Garrity-Ryan LK, McKenney D, Jackson C, Levy SB, Tanaka SK, Alekshun MN. MarA, SoxS and Rob function as virulence factors in an Escherichia coli murine model of ascending pyelonephritis. Microbiology. 2006;152:3643–3650. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/000604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champion GA, Neely MN, Brennan MA, DiRita VJ. A branch in the ToxR regulatory cascade of Vibrio cholerae revealed by characterization of toxT mutant strains. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:323–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2191585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coburn PS, Baghdayan AS, Dolan GT, Shankar N. An AraC-type transcriptional regulator encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pathogenicity island contributes to pathogenesis and intracellular macrophage survival. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5668–5676. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00930-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darwin AJ, Miller VL. Identification of Yersinia enterocolitica genes affecting survival in an animal host using signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:51–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frota CC, Papavinasasundaram KG, Davis EO, Colston MJ. The AraC family transcriptional regulator Rv1931c plays a role in the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5483–5486. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5483-5486.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauser AR, Kang PJ, Engel JN. PepA, a secreted protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is necessary for cytotoxicity and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:807–818. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hava DL, Camilli A. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1389–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowser TE, Bartlett VJ, Grier MC, Verma AK, Warchol T, Levy SB, Alekshun MN. Novel anti-infection agents: small-molecule inhibitors of bacterial transcription factors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:5652–5655. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity-Ryan LK, Kim OK, Balada-Llasat JM, Bartlett VJ, Verma AK, Fisher ML, Castillo C, Songsungthong W, Tanaka SK, Levy SB, Mecsas J, Alekshun MN. Small molecule inhibitors of LcrF, a Yersinia pseudotuberculosis transcription factor, attenuate virulence and limit infection in a murine pneumonia model. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4683–4690. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01305-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grier MC, Garrity-Ryan LK, Bartlett VJ, Klausner KA, Donovan PJ, Dudley C, Alekshun MN, Tanaka SK, Draper MP, Levy SB, Kim OK. N-Hydroxybenzimidazole inhibitors of ExsA MAR transcription factor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: In vitro anti-virulence activity and metabolic stability. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:3380–3383. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung DT, Shakhnovich EA, Pierson E, Mekalanos JJ. Small-molecule inhibitor of Vibrio cholerae virulence and intestinal colonization. Science. 2005;310:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1116739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurt JK, McQuade TJ, Emanuele A, Larsen MJ, Garcia GA. Highthroughput screening of the virulence regulator VirF: a novel antibacterial target for shigellosis. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:379–387. doi: 10.1177/1087057110362101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim OK, Garrity-Ryan LK, Bartlett VJ, Grier MC, Verma AK, Medjanis G, Donatelli JE, Macone AB, Tanaka SK, Levy SB, Alekshun MN. Nhydroxybenzimidazole inhibitors of the transcription factor LcrF in Yersinia: novel antivirulence agents. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5626–5634. doi: 10.1021/jm9006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolin A, Balasubramaniam V, Skredenske JM, Wickstrum JR, Egan SM. Differences in the mechanism of the allosteric L-rhamnose responses of the AraC/XylS family transcription activators RhaS and RhaR. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:448–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alksne LE, Burgio P, Hu W, Feld B, Singh MP, Tuckman M, Petersen PJ, Labthavikul P, McGlynn M, Barbieri L, McDonald L, Bradford P, Dushin RG, Rothstein D, Projan SJ. Identification and analysis of bacterial protein secretion inhibitors utilizing a SecA-LacZ reporter fusion system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1418–1427. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1418-1427.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simons RW, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell BS, Rivas MP, Court DL, Nakamura Y, Turnbough CL., Jr Rapid confirmation of single copy lambda prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5765–5766. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jubete Y, Maurizi MR, Gottesman S. Role of the heat shock protein DnaJ in the Lon-dependent degradation of naturally unstable proteins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30798–30803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wickstrum JR, Egan SM. Ni+-affinity purification of untagged cAMP receptor protein. Biotechniques. 2002;33:728–730. doi: 10.2144/02334bm01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhan H, Swint-Kruse L, Matthews KS. Extrinsic interactions dominate helical propensity in coupled binding and folding of the lactose repressor protein hinge helix. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5896–5906. doi: 10.1021/bi052619p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickstrum JR, Skredenske JM, Balasubramaniam V, Jones K, Egan SM. The AraC/XylS family activator RhaS negatively autoregulates rhaSR expression by preventing cyclic AMP receptor protein activation. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:225–232. doi: 10.1128/JB.00829-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickstrum JR, Skredenske JM, Kolin A, Jin DJ, Fang J, Egan SM. Transcription activation by the DNA-binding domain of the AraC family protein RhaS in the absence of its effector-binding domain. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4984–4993. doi: 10.1128/JB.00530-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egan SM, Schleif RF. DNA-dependent renaturation of an insoluble DNA binding protein. Identification of the RhaS binding site at rhaBAD. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:821–829. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou P, Wagner G. Overcoming the solubility limit with solubility-enhancement tags: successful applications in biomolecular NMR studies. J Biomol NMR. 2010;46:23–31. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Childers BM, Cao X, Weber GG, Demeler B, Hart PJ, Klose KE. Nterminal residues of the Vibrio cholerae virulence regulatory protein ToxT involved in dimerization and modulation by fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28644–28655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.