Abstract

Purpose

Controversy exists regarding adjuvant oxaliplatin treatment among older stage II and III colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. We sought to identify patient/tumor, physician, hospital, and geographic factors associated with oxaliplatin use among older patients.

Methods

Individuals diagnosed at age>65 with stage II/III CRC from 2004–2007 undergoing surgical resection and receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were identified using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program (SEER)-Medicare, a database including patient/tumor and hospital characteristics. Physician information was obtained from the American Medical Association. We used Poisson regression to identify independent predictors of oxaliplatin receipt. The discriminatory ability of each category of characteristics to predict oxaliplatin receipt was assessed by comparing the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) from logistic regression models.

Results

We identified 4,388 individuals who underwent surgical resection at 773 hospitals and received chemotherapy from 1,517 physicians. Adjuvant oxaliplatin use was higher among stage III (colon=56%, rectum=51%) compared to stage II patients (colon=37%, rectum=35%). Overall, patients who were older, diagnosed before 2006, separated, divorced or widowed, living in a higher poverty census tract or in the East or Midwest, or with higher levels of comorbidity were less likely to receive oxaliplatin. Patient factors and calendar year accounted for most of the variation in oxaliplatin receipt (AUC=75.8%).

Conclusion

Adjuvant oxaliplatin use increased rapidly from 2004–2007 despite uncertainties regarding its effectiveness in older patients. Physician and hospital characteristics had little influence on adjuvant oxaliplatin receipt among older patients.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, chemotherapy, SEER Program, Medicare

INTRODUCTION

In 2011, an estimated 141,210 patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) in the United States (US), with 49,380 deaths.1 Healthcare spending for CRC was estimated at $14.1 billion in 2010.2, 3 As the median age at CRC diagnosis is 69 years, older patients account for a substantial portion of the overall CRC disease burden in the US.4

Adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection improves overall survival among older stage III colon cancer patients. Three adjuvant chemotherapies are available and include 5-fluorouracil (FU), capecitabine, or the combination of 5-FU or capecitabine with oxaliplatin; no other agents have been shown to improve outcomes.5–8 Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU compared to surgery alone reduces the risk of death by 24% among older stage III colon cancer patients.9 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated that adding adjuvant oxaliplatin to 5-FU leads to an incremental 4.2% reduction in death among patients with stage III colon cancer.10–13 However, individuals enrolled in these RCTs had a median age at diagnosis of 60–63 years, and only 17% were ≥70 years,14 limiting the generalizability of these findings to older patients. Recent studies15–21 have shown that the addition of adjuvant oxaliplatin to 5-FU or capecitabine results in minimal, if any incremental survival benefit for older stage III colon cancer patients and average risk stage II colon cancer patients. Based upon these findings, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines now state that there is no demonstrated benefit to the addition of adjuvant oxaliplatin to 5-FU in average-risk stage II colon cancer or in patients >70 years.22 The role of adjuvant oxaliplatin in rectal cancer is not yet defined.

In light of the growing concerns regarding the incremental benefits of oxaliplatin in addition to 5-FU in these subgroups and the lack of RCT evidence regarding its role in rectal cancer, we sought to examine the dissemination of adjuvant oxaliplatin among older patients and factors influencing its use in routine clinical practice.”

METHODS

Data sources

The SEER-Medicare database is a linkage of two large population-based data sources providing detailed clinical and healthcare utilization information on Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with cancer.23 The SEER registries collect demographic, clinical and tumor characteristics, vital status, and cause of death for all incident cancers reported for individuals residing within one of the registry areas, covering approximately 28% of the US.24 Patients in SEER are linked to their Medicare Part A and B claims.25 Nearly all Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for Part A and almost 93% opt to enroll in the Part B.26 The SEER-Medicare Hospital file reports descriptive information for hospitals that are part of the SEER-Medicare database,27 including whether hospitals were NCI-designated cancer centers or participated in cooperative groups for clinical trials. Medicare claims were linked to the Hospital file using a unique number. The AMA Physician Masterfile data contain information on the characteristics of >1 million physicians in the US which are linked to Medicare claims by each physician’s Unique Physician Identification Numbers (UPINs).28–30

Study Cohort

We identified all patients in the SEER data diagnosed at age >65 with their first primary stage II or III cancer of the colon or rectum.31 Exclusions included: diagnoses at autopsy or death; a missing month of diagnosis; those without continuous Medicare Part A and B fee-for-service enrollment for the 12-months before and 8-months after diagnosis (as healthcare utilization and treatment information would not be complete for all patients).

To identify characteristics of the hospital where cancer surgery was performed, we restricted this cohort to individuals with a surgical claim (i.e., colectomy or proctectomy) in the 6-months following diagnosis. If a patient had surgical claims from multiple hospitals, the first hospital was retained for analysis. We linked the cohort to the SEER-Medicare Hospital file by the provider number and year of diagnosis for each patient. Hospitals that did not match were excluded.

To examine characteristics of physicians providing chemotherapy, eligible patients had to have at least one claim for a specific chemotherapeutic agent during the initial chemotherapy treatment period (described below). The physician with the most chemotherapy-related claims during the initial chemotherapy treatment period was considered the treating physician.32 UPINs that did not match to the AMA Physician Masterfile were excluded.

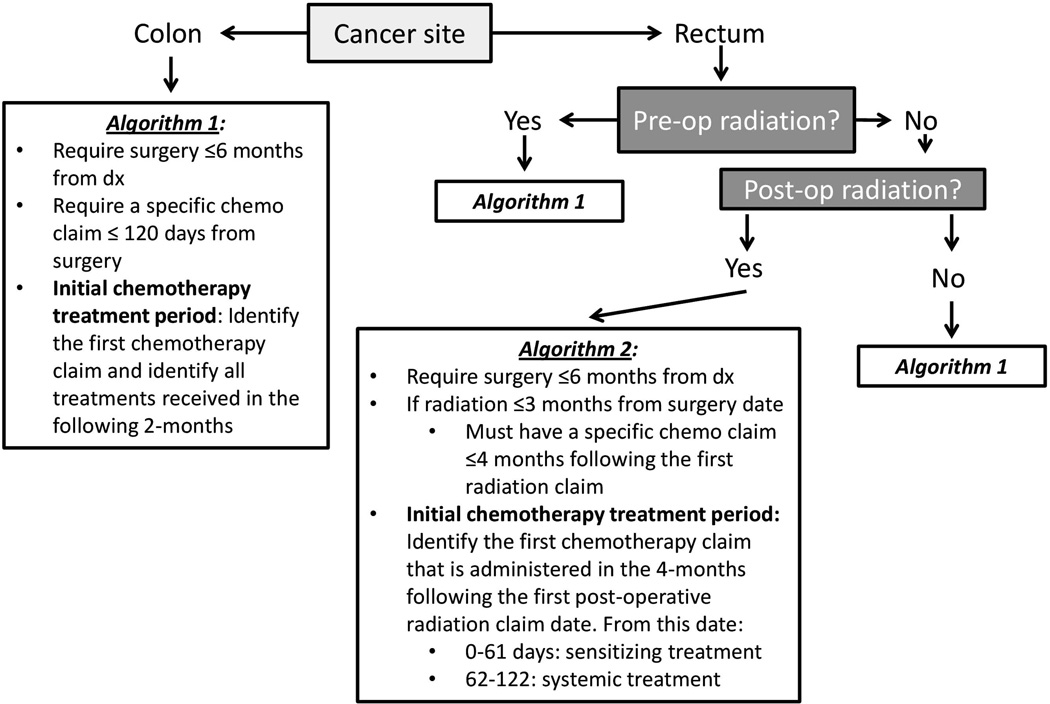

Measurement of adjuvant oxaliplatin

We categorized patients as receiving adjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin or without oxaliplatin using the algorithm in Figure 1. Because adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer may be delivered pre- or post-operatively, a different exposure window was required for patients receiving post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy to distinguish between radiosensitizing chemotherapy and systemic adjuvant chemotherapy. We defined adjuvant chemotherapy using a 120-day window to avoid misclassifying chemotherapy for recurrent cancer as adjuvant therapy. Patients were divided into an oxaliplatin group, those having ≥1 claim for oxaliplatin within 60 days from the first chemotherapy claim, and a non-oxaliplatin group, those without any oxaliplatin claims within 60 days from the first chemotherapy. The validity of Medicare claims to identify chemotherapy administration and oxaliplatin has been previously reported to be high.33, 34

Figure 1. Administrative algorithms used to define adjuvant chemotherapy treatment for stage II and III colorectal cancer patients.

Patient characteristics

Characteristics including year of diagnosis, sex, age at diagnosis (66–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, or 85+), race/ethnicity (White Non-Hispanic, Black Non-Hispanic, Other Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, or Unknown), marital status (married, single, other (divorced, separated, widowed), or unknown), and region of residence (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West) came from SEER. County-level metropolitan area was defined as metropolitan or non-metropolitan. Census tract level information about the percentage of residents living below the federal poverty level served as an aggregate measure of socioeconomic status and was categorized into quartiles: ≤4%, 4.01–≤8%, 8.01–≤15%, and >15, as the census tract poverty variable may be the best proxy measure of SES for elderly Medicare beneficiaries.35, 36 Each patient’s pre-existing health conditions in the 365 days pre-diagnosis were measured using the Klabunde adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).37

Hospital and physician characteristics

Hospital characteristics included NCI center designation (none, clinical, or comprehensive), NCI cooperative membership group count (0 or ≥1), teaching hospital status (yes/no), type of hospital (non-profit, private, or government), and total bed size, measured in quartiles (<204, 204–343, 344–487, or 488+). Physician characteristics included medical degree (Medical Doctor (MD) or Doctor of Osteopathy (DO)), whether the physician was trained in the US (yes/no), year of medical school graduation (<1981 or ≥1981), primary specialty (oncology, hematology/oncology, hematology, internal medicine, or other), and sex.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the proportion of patients receiving adjuvant oxaliplatin by year, cancer site, and stage. Bivariable prevalence ratios (PRs) for the receipt of oxaliplatin were calculated for each multilevel characteristic. Patient observations were clustered within hospitals and physicians in a non-nested manner. Our analysis accounted for this correlation and produced estimates of marginal (population-averaged) associations.38 We estimated adjusted PRs (aPRs) for all variables using multivariable Poisson models with a log link and generalized estimating equations with an independent working correlation matrix. Stratified analyses for colon and rectal cancer were performed. Finally, we assessed the discriminatory ability of a variety of logistic regression models to determine adjuvant oxaliplatin receipt by comparing the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC). Models included combinations of calendar year and patient/tumor, physician, hospital, and geographic characteristics. All analyses were conducted using the SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

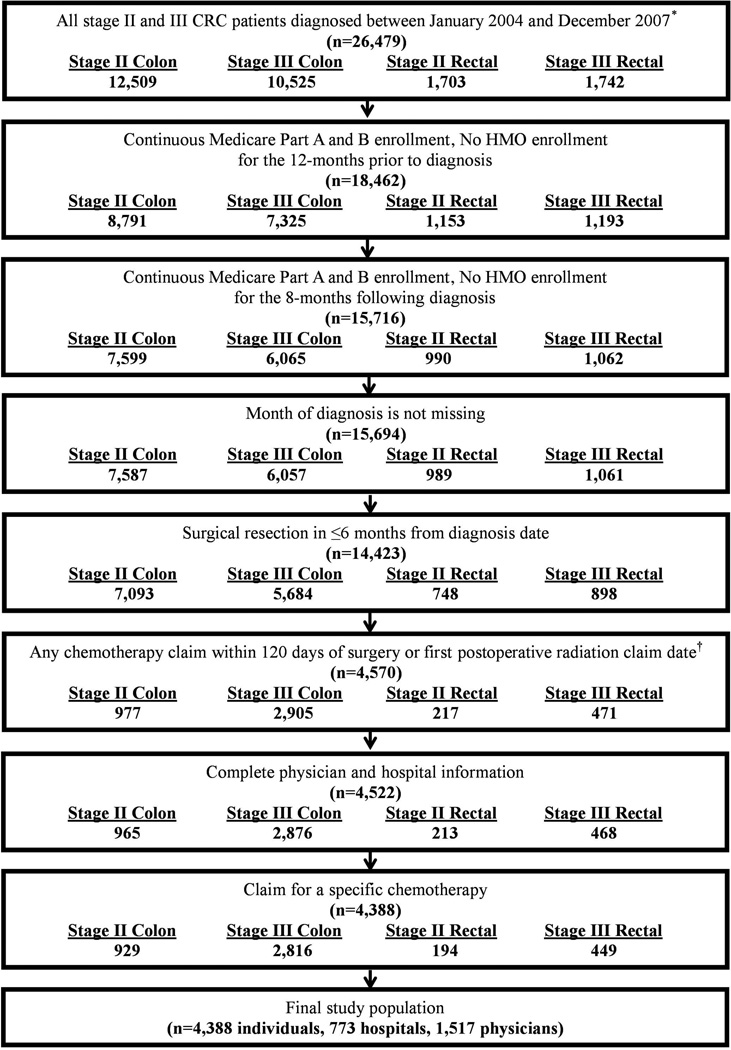

We identified 4,388 patients diagnosed with stage II or III CRC who received chemotherapy and met all eligibility criteria for inclusion (Figure 2). The study population was primarily over the age of 70 at diagnosis (73%), White Non-Hispanic (81%), married (61%), living in a metropolitan area (84%), and free from comorbidities (68%). Most tumors were located in the colon (85%) and diagnosed at stage III (74%) (Table 1).

Figure 2. Study population flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of older stage II or III colorectal cancer patients by chemotherapy treatment group*

| Patients receiving chemotherapy treatment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient and geographic characteristics | All stage II and III colorectal cancer patients |

without oxaliplatin† |

with oxaliplatin |

|||

| n=4,388 | col % | n=2,145 | row % | n=2,243 | row % | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 2,087 | 48 | 1,026 | 49 | 1061 | 51 |

| Female | 2,301 | 52 | 1,119 | 49 | 1,182 | 51 |

| Age at diagnosis (mean, SD) | 73.7 (5.3) | 74.8 (5.6) | 72.6 (4.8) | |||

| 65 – 69 | 1,199 | 27 | 456 | 38 | 743 | 62 |

| 70 – 74 | 1,360 | 31 | 624 | 46 | 736 | 54 |

| 75 – 79 | 1,144 | 26 | 584 | 51 | 560 | 49 |

| 80 – 84 | 563 | 13 | 375 | 67 | 188 | 33 |

| 85+ | 122 | 3 | 106 | 87 | 16 | 13 |

| Race | ||||||

| White Non-Hispanic | 3,551 | 81 | 1,723 | 49 | 1,828 | 51 |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 273 | 6 | 141 | 52 | 132 | 48 |

| Hispanic | 285 | 6 | 153 | 54 | 132 | 46 |

| Other Non-Hispanic | 271 | 6 | 126 | 46 | 145 | 54 |

| Unknown | 8 | 0 | 2 | 25 | 6 | 75 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 2,663 | 61 | 1,238 | 46 | 1,425 | 54 |

| Single | 291 | 7 | 136 | 47 | 155 | 53 |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 1,288 | 29 | 705 | 55 | 583 | 45 |

| Unknown | 146 | 3 | 66 | 45 | 80 | 55 |

| Percentage living below poverty level‡ | ||||||

| ≤ 4% | 1,052 | 24 | 476 | 45 | 576 | 55 |

| 4–8% | 1,250 | 28 | 579 | 46 | 671 | 54 |

| 8–15% | 1,031 | 23 | 531 | 52 | 500 | 48 |

| >15% | 1,055 | 24 | 559 | 53 | 496 | 47 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 2004 | 1,283 | 29 | 926 | 72 | 357 | 28 |

| 2005 | 1,157 | 26 | 567 | 49 | 590 | 51 |

| 2006 | 987 | 22 | 361 | 37 | 626 | 63 |

| 2007 | 961 | 22 | 291 | 30 | 670 | 70 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||||

| 0 | 2,982 | 68 | 1407 | 47 | 1575 | 53 |

| 1 | 1,029 | 23 | 534 | 52 | 495 | 48 |

| 2+ | 377 | 9 | 204 | 54 | 173 | 46 |

| Tumor characteristics at diagnosis | ||||||

| Cancer site | ||||||

| Colon | 3,745 | 85 | 1,799 | 48 | 1,946 | 52 |

| Rectum | 643 | 15 | 346 | 54 | 297 | 46 |

| AJCC/Derived AJCC stage | ||||||

| II | 1,123 | 26 | 713 | 63 | 410 | 37 |

| III | 3,265 | 74 | 1,432 | 44 | 1,833 | 56 |

| Geographic characteristics | ||||||

| County of residence size (metro area)‡ | ||||||

| Metropolitan | 3,685 | 84 | 1,765 | 48 | 1,920 | 52 |

| Non-metropolitan | 703 | 16 | 380 | 54 | 323 | 46 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1,045 | 24 | 544 | 52 | 501 | 48 |

| South | 873 | 20 | 441 | 51 | 432 | 49 |

| Midwest | 716 | 16 | 389 | 54 | 327 | 46 |

| West | 1,754 | 40 | 771 | 44 | 983 | 56 |

Cases obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program 17 registries were included in this analysis.

94% of the individuals who received treatment without oxaliplatin (n=2,473) received 5-FU or capecitabine alone. All remaining individuals (n=163) received another combination of chemotherapy agents.

Percentage of census tract living below the poverty line and county of residence in metro area size are linked from 2000 Census data.

The majority of the 1,517 physicians were male (81%), MDs (97%), US-trained (67%), medical school graduates ≥1981 (56%) with a primary specialty of oncology or hematology/oncology (76%) (Table 2). Three percent of the 773 hospitals had a NCI clinical or comprehensive cancer center designation and 48% had at least one cooperative group membership. Almost 40% were teaching hospitals and 62% were non-profit entities.

Table 2.

Characteristics of physicians and hospitals providing care for older stage II and III colorectal cancer patients

| Characteristic | Physicians/ hospitals included in analysis |

Patients receiving chemotherapy treatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| without oxaliplatin* |

with oxaliplatin | |||||

| n | col% | n=2,145 | row % | n=2,243 | row % | |

| Physician characteristics (n=1,517) | ||||||

| Degree | ||||||

| MD | 1,464 | 97 | 2,049 | 49 | 2,174 | 51 |

| DO | 53 | 3 | 96 | 58 | 69 | 42 |

| US-Trained | ||||||

| Yes | 1,012 | 67 | 1,351 | 47 | 1,524 | 53 |

| No | 505 | 33 | 794 | 52 | 719 | 48 |

| Medical School Graduation | ||||||

| <1981 | 666 | 44 | 1,025 | 51 | 1,001 | 49 |

| ≥1981 | 851 | 56 | 1,120 | 47 | 1,242 | 53 |

| Primary specialty | ||||||

| Oncology | 681 | 45 | 1,023 | 48 | 1,095 | 52 |

| Hematology/Oncology | 477 | 31 | 660 | 50 | 673 | 50 |

| Hematology | 160 | 11 | 223 | 48 | 237 | 52 |

| Internal Medicine | 133 | 9 | 188 | 50 | 189 | 50 |

| Other specialty | 66 | 4 | 51 | 51 | 49 | 49 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1,235 | 81 | 1,832 | 49 | 1,925 | 51 |

| Female | 282 | 19 | 313 | 50 | 318 | 50 |

| Hospital characteristics (n=773 unique) † | ||||||

| NCI center designation | ||||||

| None | 802 | 97 | 2,091 | 49 | 2,158 | 51 |

| Clinical | 4 | 0 | 7 | 39 | 11 | 61 |

| Comprehensive | 20 | 2 | 47 | 39 | 74 | 61 |

| NCI cooperative group membership count | ||||||

| None | 426 | 52 | 730 | 51 | 709 | 49 |

| 1+ | 400 | 48 | 1,415 | 48 | 1,534 | 52 |

| Teaching hospital | ||||||

| Yes | 319 | 39 | 1,153 | 50 | 1,142 | 50 |

| No | 502 | 61 | 988 | 47 | 1,098 | 53 |

| Unknown | 5 | 1 | 4 | 57 | 3 | 43 |

| Type of hospital | ||||||

| Non-profit | 512 | 62 | 1,693 | 50 | 1,706 | 50 |

| Private | 154 | 19 | 225 | 46 | 259 | 54 |

| Government | 155 | 19 | 223 | 45 | 275 | 55 |

| Unknown | 5 | 1 | 4 | 57 | 3 | 43 |

| Total bed size | ||||||

| < 204 beds | 381 | 46 | 550 | 50 | 554 | 50 |

| 204 – 343 beds | 197 | 24 | 531 | 49 | 563 | 51 |

| 344 – 487 beds | 134 | 16 | 521 | 48 | 575 | 52 |

| 488+ beds | 113 | 14 | 543 | 50 | 550 | 50 |

NCI=National Cancer Institute

94% of the individuals who received treatment without oxaliplatin (n=2,473) received 5-FU or capecitabine alone. All remaining individuals (n=163) received another combination of chemotherapy agents.

All hospital information was obtained from the year of patient diagnosis with exception of the NCI cancer center designation and cooperative group count which are reported for the year 2002. The total number of hospitals reported here (n=874) is greater than the total number of unique hospitals because some of the hospital characteristics changed over time and are reported here according to year of the patient's cancer diagnosis.

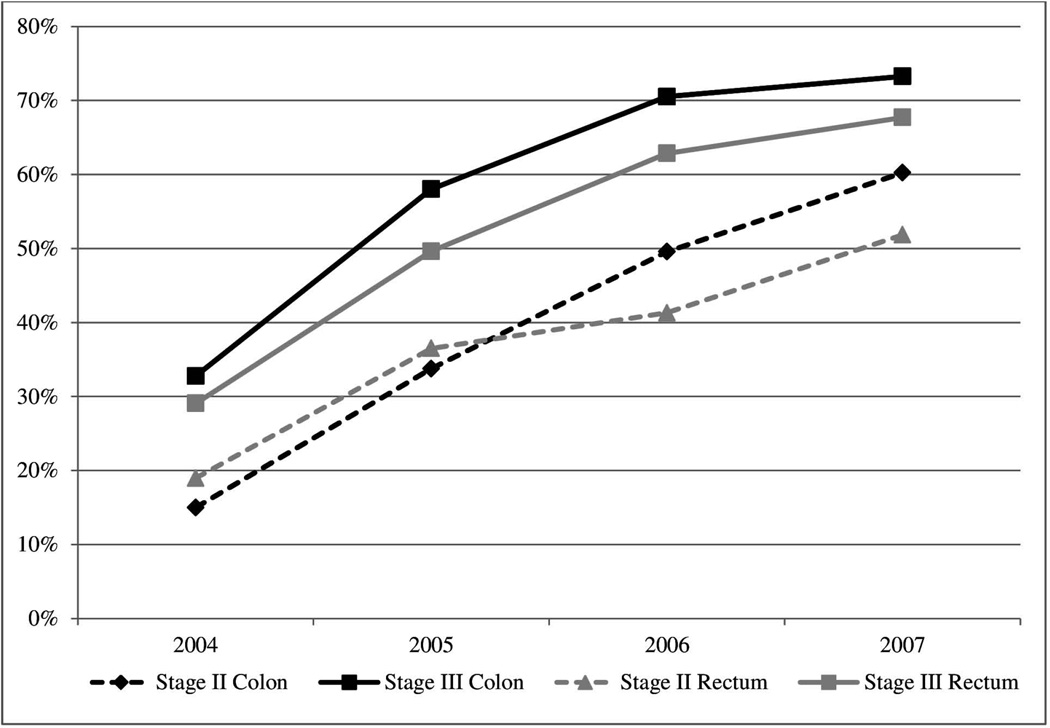

The prevalence of adjuvant oxaliplatin treatment over the 4-year study period was 52% and 46% for patients diagnosed with colon and rectal cancer, respectively. There was a steady increase in the prevalence of adjuvant oxaliplatin use over time which was similar for all site and stage subgroups (Figure 3). By 2007, 60% and 73% of stage II and III colon and 52% and 68% of stage II and III rectal cancer patients received oxaliplatin, respectively.

Figure 3. Prevalence of adjuvant oxaliplatin use by cancer site and stage among older colorectal cancer patients who received chemotherapy treatment from 2004–2007.

The annual prevalence among stage II and III colon cancer patients is represented by the black dashed and solid line, respectively, and among stage II and III rectal cancer patients by the grey dashed and solid line, respectively. Less than 3% (n=114) of patients received adjuvant irinotecan during the study period.

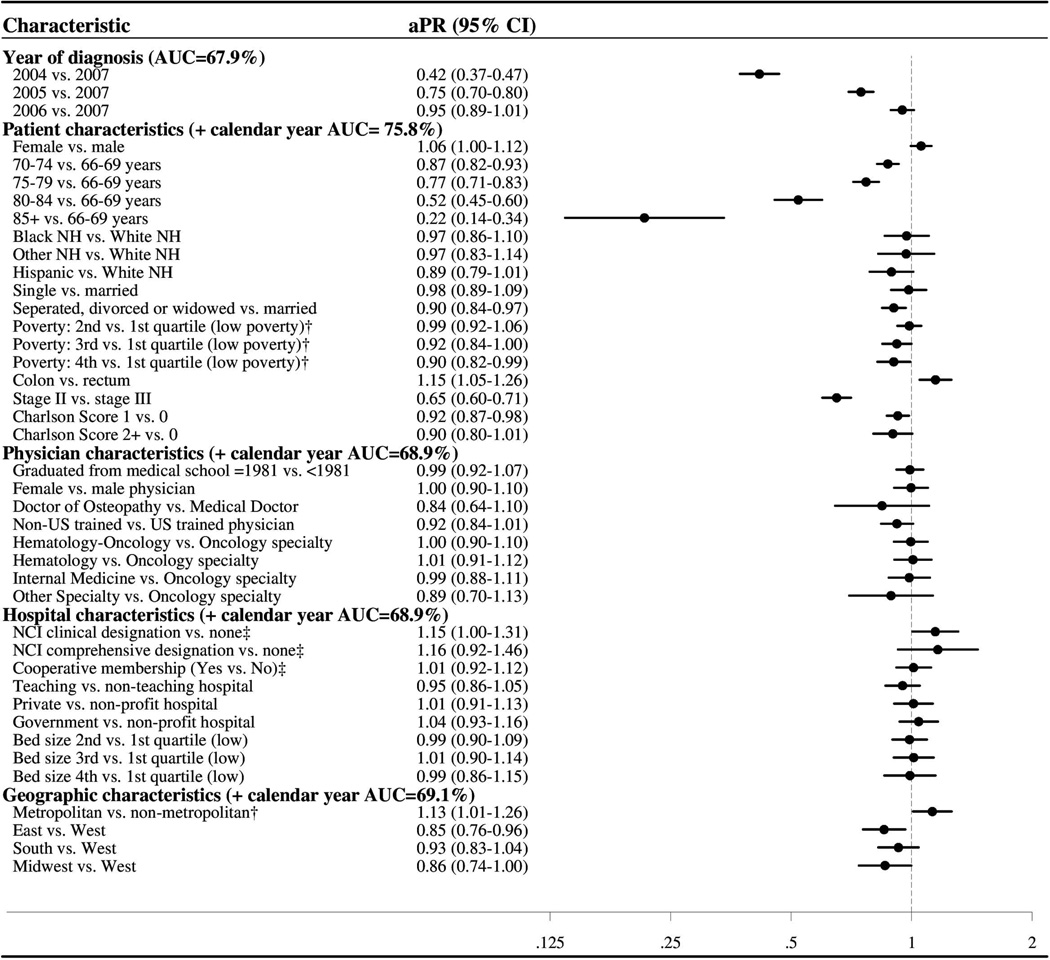

Patients diagnosed in earlier years were less likely to receive adjuvant oxaliplatin than those diagnosed in 2007 (e.g., 2004: aPR=0.42, 95% CI: (0.37, 0.47), Figure 4). Patients with colon vs. rectal cancer were more likely to receive oxaliplatin (aPR=1.15, 95% CI: (1.05, 1.26)), whereas those with stage II vs. III disease were less likely (aPR= 0.65, 95% CI: (0.60, 0.71)). Increasing age was associated with a gradual monotonic decrease in the likelihood of oxaliplatin receipt (e.g., 85+ vs. 66–69: aPR =0.22, 95% CI: (0.14, 0.34)) and patients with increased comorbidities were less likely to receive oxaliplatin compared to those with no comorbidity (e.g., Charlson Score of 1 vs. 0: aPR= 0.92, 95% CI: (0.87, 0.98). Additionally, patients who were separated, divorced or widowed (vs. married), living in the East or Midwest (vs. West), residing in a non-metropolitan area (vs. metropolitan area) or in a census tract with a higher proportion of individuals living under the poverty level were less likely to receive oxaliplatin. No physician- or hospital-level variables were strongly associated with adjuvant oxaliplatin receipt in the overall analysis. Results from the cancer site-stratified analyses were similar, although less precise for rectal cancer due the smaller number of patients (data not shown). Two exceptions were that among rectal cancer patients, surgical treatment at an NCI comprehensive cancer center was associated with increased adjuvant oxaliplatin use (aPR=1.48, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.90), while Hispanic ethnicity was associated with decreased use (aPR=0.52, 0.32, 0.86). Among stage II colon cancer patients, more patients with T4 tumors (40%) received oxaliplatin compared to those with T3 tumors (36%).

Figure 4. Forest plot summarizing the multivariable adjusted prevalence ratio estimates for the associations between multilevel characteristics and adjuvant oxaliplatin receipt among older stage II and III CRC patients treated with chemotherapy.

The category headings in Figure 4 denote the AUC for components of the logistic regression model (calendar year, patient/tumor, physician, hospital, and geographic). The AUC reports the ability of each model to accurately distinguish between those patients who received adjuvant oxaliplatin and those who did not. When calendar year was included alone, the model had fair ability to discriminate oxaliplatin users (AUC=68%). The addition of patient/tumor factors enhanced the model’s discriminatory ability (AUC=75.8 %). However, when physician, hospital, and geographic factors were added separately to calendar year, the AUC only increased to 68.9%, 68.9%, and 69.1% respectively. The full model AUC was 76.6%; therefore, among patients who received chemotherapy, physician and hospital characteristics contributed very little to the determination of oxaliplatin receipt.

DISCUSSION

This population-based analysis demonstrates substantial increases in oxaliplatin use among older stage II and III CRC patients who received chemotherapy from 2004–2007. By 2007, the prevalence of oxaliplatin treatment was 60% and 73% among stage II and III colon cancer patients and 52% and 68% among stage II and III rectal cancer patients, respectively. Patient- and tumor-level characteristics, together with calendar year, accounted for most of the discriminatory power in determining oxaliplatin use in older CRC patients, while physician and hospital characteristics contributed little.

Patients treated by providers within the Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), a network connecting NCI cooperative groups to community physicians treating cancer patients, were recently found to be more likely than those who did not to receive adjuvant oxaliplatin.39 CCOP data was not available for our analysis; however, when restricted to stage III colon cancer patients, we did not find an association between hospital cooperative group participation and adjuvant oxaliplatin use (aPR=0.98, 95% CI: 0.91, 1.05). This discrepancy may reflect that our study examined a slightly later time period, potentially weakening the impact of cooperative group membership on oxaliplatin diffusion. By 2007, 73% of all older stage III colon cancer patients in our study received adjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin, suggesting that its adoption in routine practice was rapid and widespread across all physicians. However, our finding that rectal cancer patients undergoing surgery at an NCI comprehensive cancer centers were more likely to receive adjuvant oxaliplatin compared with similar patients at hospitals without an NCI designation may be due to the unique timing and coordination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy required for rectal cancer treatment. The sex and race/ethnicity of patients were not predictive of adjuvant oxaliplatin receipt, which may reflect the uniform insurance setting of our study limiting variations in access to care.

Among patient subgroups where RCT evidence is entirely lacking (i.e., stage II and III rectal cancer) or has shown no benefit (i.e., stage II colon cancer),11 we found widespread adjuvant oxaliplatin use by 2007 in older CRC patients. Well over half of all stage II colon and stage II and III rectal cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy received oxaliplatin as part of their adjuvant chemotherapy. Rectal cancer patients have not been included in RCTs examining adjuvant oxaliplatin and as such, there is no phase III evidence supporting its use. It is possible that higher local and systemic recurrence rates lead physicians and older patients to choose adjuvant oxaliplatin treatment;40, 41 however, the added toxicity of (neo)adjuvant radiotherapy makes tolerance of adjuvant chemotherapy more challenging. Whether this practice is appropriate will hopefully be answered by ongoing trials examining the role of oxaliplatin in adjuvant chemotherapy of rectal cancer (PETACC 6 and German Rectal Cancer Study Group CAO/ ARO/AIO-04). However, these trials are unlikely to include adequate numbers of older rectal cancer patients for sub-analysis, and therefore some uncertainty will remain.

Even in colon cancer, the evidence to support the addition of adjuvant oxaliplatin to 5-FU in older patients is weak. An initial pooled analysis of four RCTs demonstrated that the efficacy of adding oxaliplatin to 5-FU was similar in older and younger patients with stage III and metastatic CRC.14 However, three recent RCT analyses relying on subgroup or pooled data have reported conflicting results regarding the efficacy of adjuvant oxaliplatin in older patients.19, 20, 42 Two analyses of multiple observational databases found that the addition of adjuvant oxaliplatin treatment may benefit those younger than 75 years old,17 but for those ≥80 any benefit is likely modest.18 Therefore, as controversy remains regarding adjuvant oxaliplatin in older stage III colon cancer patients, any potential benefits must be carefully considered alongside patient preferences and the cost and risk of adverse events.

Our study has multiple strengths. The cohort included a large sample derived from population-based cancer registries linked to longitudinal Medicare claims. These data were augmented by information in the AMA Masterfile and SEER-Medicare Hospital file. The aggregation of data resulted in a rich data source to examine the influence of multilevel characteristics on the receipt of oxaliplatin. Our analysis reflects patterns of chemotherapy use in the community setting.

However, our study is limited by the constraints of the data sources. SEER-Medicare contains information on many patient and tumor characteristics that may be associated with treatment patterns, but unobserved factors such as patient preferences, financial considerations, or functional status may also influence treatment decisions. Further linkage efforts to data sources including electronic medical records or patient surveys may improve measurement of these factors for future research. Because clinical stage was not available in the SEER data, we relied upon pathological staging and as a result may have selected neoadjuvantly-treated rectal cancer patients with a poorer prognosis. Our analysis did not examine within-physician variation in prescribing using a random effects framework, which may further illuminate patterns of physician preference regarding the use of oxaliplatin. Lastly, a number of exclusions were made in the creation of our study population and thus the findings from our analysis may not be generalizable to individuals <66 years or managed care enrollees.

In conclusion, adjuvant oxaliplatin was increasingly used to treat stage II and III CRC patients following its approval in 2004 and its use was influenced strongly by patient, as opposed to physician or hospital, characteristics. By 2007, 70% of all chemotherapy-treated stage II and III CRC patients received adjuvant oxaliplatin, despite no evidence to support its use in rectal cancer, and mounting evidence against its use in stage II and older stage III colon cancer patients. The widespread dissemination of oxaliplatin into the older population highlights the critical importance of studying the benefits of anticancer therapies in older patient populations. Future studies should focus on the comparative effectiveness and safety of adjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin in older stage II and III rectal cancer patients, as utilization within these patient groups were substantial and the evidence for benefit and harm are unknown.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (T32 DK07634). Other co-author funding includes NIH RO1AG023178 (TS), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (TS), National Cancer Institute (NCI) K07CA16077 (HKS), and unrestricted research grants from Merck and Sanofi (TS).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edler L, Heim ME, Quintero C, Brummer T, Queisser W. Prognostic factors of advanced colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1986;22:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(86)90325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, Mariotto A. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2006–2014. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, Edwards BK, editors. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2008. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltz LB, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Irinotecan fluorouracil plus leucovorin is not superior to fluorouracil plus leucovorin alone as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer: results of CALGB 89803. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:3456–3461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1383–1393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, et al. Phase III trial assessing bevacizumab in stages II and III carcinoma of the colon: results of NSABP protocol C-08. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 29:11–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Cutsem E, Labianca R, Bodoky G, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:3117–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1091–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1465–1471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O'Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H, et al. Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4085–4091. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dotan E, Browner I, Hurria A, Denlinger C. Challenges in the management of older patients with colon cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:213–224. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0020. quiz 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Freburger J, et al. Comparison of adverse events during 5-fluorouracil versus 5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: A Population-based analysis. Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Martin CF, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Oxaliplatin vs Non-Oxaliplatin-containing Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:211–227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Sturmer T, et al. Effect of Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Survival of Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer Diagnosed After Age 75 Years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2624–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tournigand C, Andre T, Bonnetain F, et al. Adjuvant Therapy With Fluorouracil and Oxaliplatin in Stage II and Elderly Patients (between ages 70 and 75 years) With Colon Cancer: Subgroup Analyses of the Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3353–3360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277:1485–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Allegra CJ, et al. Oxaliplatin As Adjuvant Therapy for Colon Cancer: Updated Results of NSABP C-07 Trial, Including Survival and Subset Analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemeny N, Braun DW., Jr Prognostic factors in advanced colorectal carcinoma. Importance of lactic dehydrogenase level, performance status, and white blood cell count. Am J Med. 1983;74:786–794. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40 doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. IV-3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel EL., Jr Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Cancer Institute. SEER-Medicare Data. [Accessed January 20, 2010];2009 May; http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/overview/seermed_fact_sheet.pdf.

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of Information Services: Data from the 100 percent Denominator File. Table 2.1 - Medicare Enrollment. [Accessed: August 20, 2011]; Available at: https://www.cms.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/08_2011.asp.

- 27.Desch CE, Benson AB, 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT) investigators. Lancet. 1995;345:939–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldwin LM, Adamache W, Klabunde CN, Kenward K, Dahlman C, J LW. Linking physician characteristics and medicare claims data: issues in data availability, quality, and measurement. Med Care. 2002;40 doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00012. IV-82-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollack LA, Adamache W, Eheman CR, Ryerson AB, Richardson LC. Enhancement of identifying cancer specialists through the linkage of Medicare claims to additional sources of physician specialty. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:562–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, et al. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:485–493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolmark N, Rockette H, Wickerham DL, et al. Adjuvant therapy of Dukes' A, B, and C adenocarcinoma of the colon with portal-vein fluorouracil hepatic infusion: preliminary results of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol C-02. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1990;8:1466–1475. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.9.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A, et al. Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Med Care. 2002;40 doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020944.17670.D7. IV-55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harmon JW, Tang DG, Gordon TA, et al. Hospital volume can serve as a surrogate for surgeon volume for achieving excellent outcomes in colorectal resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:404–411. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00013. discussion 411–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Du XL, Fang S, Vernon SW, et al. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:660–669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandelblatt JS, Kerner JF, Hadley J, et al. Variations in breast carcinoma treatment in older medicare beneficiaries: is it black or white. Cancer. 2002;95:1401–1414. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miglioretti DL, Heagerty PJ. Marginal modeling of nonnested multilevel data using standard software. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:453–463. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter WR, Meyer AM, Wu Y, et al. Translating Research Into Practice: The Role of Provider-based Research Networks in the Diffusion of an Evidence-based Colon Cancer Treatment Innovation. Med Care. 2012;50:737–748. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824ebe13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:1797–1806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta SK, Lamont EB. Patterns of presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in older patients with colon cancer and comorbid dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1681–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1407–1427. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]