ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

There is growing evidence that even small and solo primary care practices can successfully transition to full Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) status when provided with support, including practice redesign, care managers, and a revised payment plan. Less is known about the quality and efficiency outcomes associated with this transition.

OBJECTIVE

Test quality and efficiency outcomes associated with 2-year transition to PCMH status among physicians in intervention versus control practices.

DESIGN

Randomized Controlled Trial.

PARTICIPANTS

Eighteen intervention practices with 43 physicians and 14 control practices with 24 physicians; all from adult primary care practices.

INTERVENTIONS

Modeled on 2008 NCQA PPC®-PCMH™, intervention practices received 18 months of tailored practice redesign support; 2 years of revised payment, including up to $2.50 per member per month (PMPM) for achieving quality targets and up to $2.50 PMPM for PPC-PCMH recognition; and 18 months of embedded care management support. Controls received yearly participation payments.

MAIN MEASURES

Eleven clinical quality indicators from the 2009 HEDIS process and health outcomes measures derived from patient claims data; Ten efficiency indicators based on Thomson Reuter efficiency indexes and Emergency Department (ED) Visit Ratios; and a panel of costs of care measures.

KEY RESULTS

Compared to control physicians, intervention physicians significantly improved TWO of 11 quality indicators: hypertensive blood pressure control over 2 years (intervention +23 percentage points, control –2 percentage points, p = 0.02) and breast cancer screening over 3 years (intervention +3.5 percentage points, control −0.4 percentage points, p = 0.03). Compared to control physicians, intervention physicians significantly improved ONE of ten efficiency indicators: number of care episodes resulting in ED visits was reduced (intervention −0.7 percentage points, control + 0.5 percentage points, p = 0.002), with 3.8 fewer ED visits per year, saving approximately $1,900 in ED costs per physician, per year. There were no significant cost-savings on any of the pre-specified costs of care measures.

CONCLUSIONS

In a randomized trial, we observed that some indicators of quality and efficiency of care in general adult primary care practices transitioning to PCMH status can be significantly, but modestly, improved over 2 years, although most indicators did not improve and there were no cost-savings compared with control practices. For the most part, quality and efficiency of care provided in unsupported control practices remained unchanged or worsened during the trial.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2386-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: patient centered care, outcomes, randomized trials, primary care

INTRODUCTION

The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) is seen as a method to achieve the triple aim1 of reducing costs while increasing quality and patient experience in primary care. Strong evidence of the effectiveness of the PCMH model is limited2 but growing, according to the evidence review conducted by researchers at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and Mathematica Policy Research.3 Among the six studies meeting their evidence standards and including at least three of five PCMH characteristics while measuring triple aim, patient or professional experience outcomes, findings included only one report of significant cost savings.4 Others reported increased costs,5 and suggestive but inconclusive cost savings.6,7 Half of the studies reported significant and positive reductions in hospital use,5,8,9 while half reported suggestive but inconclusive findings. Only one reported reductions in emergency department visits (ED),9,10 and one reported suggestive but inconclusive reductions in ED visits.6 Two studies reported significant improvements in quality of care processes11 and/or outcomes.9,11 These studies,3 with their adequate power, design and evaluation rigor, focus on older,6,9–12 low income,10 high risk,6 and unique populations such as homebound Veterans,5 and therefore lack generalizability to the vast majority of primary care practices in the U.S. that may be considering or attempting the PCMH transition.

In our randomized, controlled, longitudinal study in a general adult population, we have shown that provision of tailored practice redesign and embedded care management support plus revised reimbursement increases the likelihood that community-based, solo and small practices can make the transition to full or nearly full recognition of Physician Practice Connections®─Patient-Centered Medical Home™ 2008 (PPC®-PCMH™)13 status awarded by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) compared to peer practices without supports or revised payment. Of note, such support results in relatively rapid change (on average 7 months), with 95 % of intervention and 21 % of controls obtaining 2008 PPC®-PCMH™ recognition by 18 months.14 This paper investigates changes in quality of care (both process and patient outcomes), and efficiency of care that follow from being provided a supportive PCMH transition package compared to attempting the transition without support.

METHODS

Design

This two-year randomized controlled trial was conducted between January 2008 and December 2010 by EmblemHealth, Inc. and evaluated by the University of Connecticut Health Center (UCHC). Detail on the design and protocol are published elsewhere.14,15 The study was determined not to be human subjects’ research by the UCHC Institutional Review Board. Practices were solo (< 2 physicians), small (2–10 physicians), or multi-site (solo or small), all in New York. Participating practitioners were specialists in internal, general, or family medicine, and included a mix of HMO, PPO, Medicaid and Medicare patients. EmblemHealth, Inc. provides a variety of PPO, EPO and HMO plans, and prescription drugs, dental, and vision care coverage to approximately 2.8 million people through a choice of networks throughout New York, acute care hospitals across the tri-state area, and physicians and hospitals across all 50 states.

Recruitment

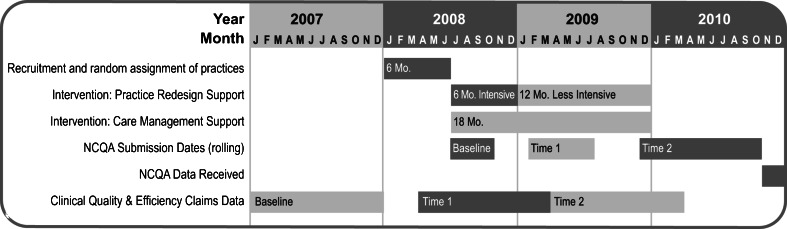

Practices were recruited and enrolled by EmblemHealth in two waves during January 2008 to June 2008 (see Timeline in Fig. 1). During enrollment, practices were notified they would be randomly assigned to study condition (to receive support or not), for 2 years. After rank-ordering by EmblemHealth’s data on patient panel size, 243 solo and small practices were targeted, for recruitment of a maximum of 50 practices.

Figure 1.

Study timeline.

Randomization

Practices were randomly assigned to condition (intervention or control) by external evaluators (JAB) by use of 1:1 urn randomization,16 stratified on four factors: 1) number of participating physicians at the practice (1 versus 2 or more); 2) Federally Qualified Health Center status (yes or no); 3) median household income by practice zip code; and 4) electronic health record (EHR) status at baseline (yes or under contract versus none).

Timeline and Protocol

After randomization, intervention received a three-part support package delivered over 2 years (see Timeline in Fig. 1), after which all supports were withdrawn. The intervention was designed to provide physician-led practice teams with guidance, tailored practice redesign support, embedded care managers, and a revised payment plan to allow them to undertake practice transformations necessary to qualify for PCMH recognition with the NCQA 2008 PPC®-PCMH™ recognition criteria.13

Practice Redesign Support

Intervention received 6 months of intensive, and 12 months of less intensive, tailored practice redesign support by a dedicated practice redesign facilitator. Facilitators engaged physicians and staff on-site in a series of activities to implement the PCMH model, such as utilizing EHR more effectively, and changing workflow to enhance efficiency and access. Specific changes included coding improvements, same-day scheduling, enhancing use of EHRs, and redesign of office space to enhance workflow.

Care Management Support

Intervention received 18 months of care management support provided by nurse care managers embedded in practice care teams (1.0 FTE care manager per 1,000 EmblemHealth patients, regardless of severity). In addition to general care coordination functions and “hot spotting”17,18 with frequent Emergency Department (ED) users, care managers identified, contacted, and engaged complex EmblemHealth patients to educate and provide guideline-based care, both one-on-one and in groups.

Revised Payment

In addition to their EmblemHealth negotiated fees, intervention received 2 years of a revised payment plan including cost of NCQA’s 2008 PPC®-PCMH™13 application fee, and Pay-For-Performance (P4P) incentives of up to $2.50 per member per month (PMPM) for improvements in 2008 PPC®-PCMH™, and up to $2.50 PMPM for improvements in clinical quality. Using HEDIS19 definitions of clinical quality, P4P targets were derived from Northeast Business Group on Health, NCQA’s Quality Compass®,20 and EmblemHealth data. Controls received participation payments of $5,000/year if compliant with data submission requirements.

Measures

Study measures were identified a priori and harmonized with those recommended by Commonwealth Fund PCMH Evaluators’ Collaborative.21

Data

As this study evaluates practices’ transition to PCMH status, the providers in each practice are the unit of the intervention. Consequently, aggregated claims data are treated as a characteristic of the physician’s care, and outcomes are evaluated at the level of the intervention physician (i-physician) and control physician (c-physician).22 Claims data were aggregated over yearly intervals to construct each of three study periods: Baseline/Pre-intervention, Time 1/Intervention and Time 2/Post-intervention (see Timeline in Fig. 1).

Efficiency

Efficiency indexes provide a measure of physician performance compared to the benchmark performance of EmblemHealth peers in terms of the dollar cost of an episode of care. Values greater than 1.0 indicate relative physician inefficiency and values under 1.0 indicate relative efficiency. Indexes are created by Thomson Reuters using their Medical Episode Grouper (MEG) and MarketScan® Databases to create comprehensive, severity- and complexity-adjusted costs for episodes of care.23 In-depth description of this ThompsonReuters methodology is in Appendix 1; available online.

Two additional indicators of efficiency are visit ratios indicating how many of a physician’s episodes of care during a year were linked with an ED visit or a hospitalization. These ratios compare a physician’s ED visits and/or hospitalizations to all of his/her episodes of care in a study period. An episode can have multiple ED visits or hospitalizations that are counted separately. A fourth indicator of efficiency is actual costs, including total, ED, hospitalization, and outpatient costs accrued in each study period.

Clinical Quality

Quality in both the process and outcomes of a physician’s care over a study period is measured using 2009 NCQA Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) Report Card19 specifications and EmblemHealth patient claim data, summarized at the physician level. Process measures included: age-relevant, sex-relevant and diagnosis-relevant screening for breast cancer (yearly rates); Chlamydia; diabetic-Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), HbA1c, and nephropathy; as well as coronary artery disease-LDL-C (CAD). Health outcome measures at the physician level are indicated by “control,” defined as the number of EmblemHealth patients in the physician’s panel meeting HEDIS control definitions on a given indicator reported by CPT-II codes (e.g., hypertensive patients with blood pressure [BP] < 140/90) over all of the relevant patients (e.g., all hypertensives) in the panel during the study period of interest (i.e., Time 2/post-intervention). If a CPT-II code was not submitted during the study period, the patient was not included in the numerator or the denominator. Control measures for each study period included: CAD LDL-C < 100 mg/dl, diabetic HbA1c < 7 %, diabetic LDL-C < 100 mg/dl, diabetic BP < 130/80, hypertensive BP < 140/90. CPT-II codes for BP values were not available for baseline, hence reliabilities were added to account for model violations due to too few repeated measures.24–27

Transformations

To create normally distributed measures, clinical quality measures were first recalculated with the arcsine transformation for proportions to adjust the tail ends of the distribution (0 and 1).28 Natural Log (LN) transformations were used only for skewed distributions.29

Analytical Approach

Descriptives and univariate tests of significance, means, standard deviations, medians, minimum and maximum values for descriptive data were produced. To test baseline differences between study groups, we conducted Independent Samples t-tests for normally distributed data, Mann-Whitney U tests for non-parametric data, and Pearson Chi-Square tests for proportional data.

Hierarchical Linear Models

To assess whether physician change occurs over time differentially by intervention group, the main effect for time x intervention was assessed with Multilevel Models (MLM) using HLM.30,31 Refer to Appendix 2 (available online) for MLM model coefficients and confidence intervals.

Weighting

To account for the unequal size of patient panels and to create more precise estimates, weights were created based on physician panel size. Thus, more weight is given to the model estimates for physicians contributing more data.

Cluster Adjustment

We did not apply cluster adjustment for physicians nested within practices, because 74 % of the EmblemHealth physicians are in small practices with two or fewer physicians, and to conduct such analyses, Hox recommends a minimum of 30 within the cluster.32

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

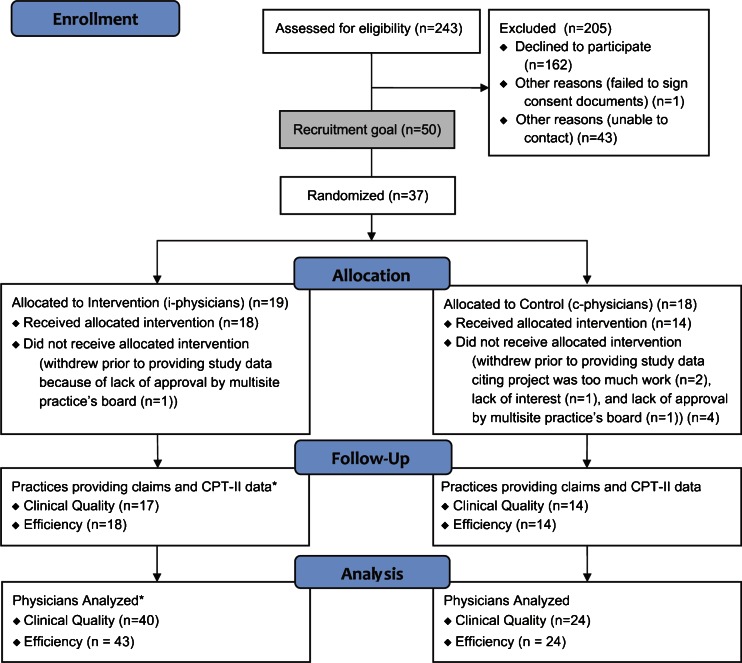

Figure 2 shows enrollment and retention of practices and physicians by condition.14 Fifteen percent (37/243) of targeted practices enrolled in the study, 74 % of the recruitment goal (37/50). Five practices (14 %) withdrew prior to providing study data, citing project burden (2), lack of board approval (2), and lack of interest (1). Table 1 shows that at baseline, the only significant difference between intervention and control practices was that intervention practices had significantly more outpatient visits for all episode types than controls (p = 0.02). Compared with control practices, intervention practices’ patients were from zip codes that were not significantly different on U.S. Census population characteristics, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, household size, employment, income, education, US born, or English speaking characteristics (see Appendix 3, available online).

Figure 2.

Enrollment and retention. * Differences in the N between clinical quality and efficiency data sets at both the practice and provider level are due to one practice that did not submit required CPT-II data or did not have qualifying patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Intervention Versus Control Practices (N = 32)

| Variables | Intervention (N = 18) | Control (N = 14) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians per Practice, Median (IQR) | 2 (9) | 2 (5) | 0.729 |

| Locations per Practice, Median (IQR) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.706 |

| EmblemHealth Patients per Practice, Mean (SD) | 407 (221) | 409 (185) | 0.776 |

| EmblemHealth Patients per Physician, Mean (SD) | 203 (89) | 246 (151) | 0.360 |

| Household Income of Practice Zip Code, Mean (SD) | $61,752 ($15,873) | $61,746 ($24,196) | 0.999 |

| Practices with Federally Qualified Health Center Status, % (n) | 6 % (1) | 0 % (0) | 1.000 |

| Practices with Electronic Health Record, % (n) | 50 % (9) | 50 % (7) | 1.000 |

| EmblemHealth Patients with Diabetes per Practice | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8 (4) | 9 (7) | 0.905 |

| Median*,† | 8 | 7 | |

| Emergency Room Visits for All Procedure Types | |||

| Mean (SD) | 81 (43) | 68 (52) | 0.135 |

| Median*, ‡, §, ‖ | 75 | 45 | |

| Hospital Admission Visits for All Procedure Types | |||

| Mean (SD) | 32 (17) | 29 (21) | 0.065 |

| Median*, ‡, § | 32 | 25 | |

| Outpatient Visits for All Procedure Types | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4,161 (2,685) | 2,750 (1,581) | 0.022 |

| Median*, ‡, § | 3,037 | 2,346 | |

| Emergency Room Visits for Cardiovascular Procedure Types | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11 (7) | 11 (9) | 0.491 |

| Median*, ‡, §, ‖ | 8 | 8 | |

| Hospital Admission Visits for Cardiovascular Procedure Types | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9 (5) | 9 (10) | 0.119 |

| Median*, ‡, §, ‖ | 9 | 6 | |

| Outpatient Visits for Cardiovascular Procedure Types | |||

| Mean (SD) | 571 (451) | 496 (259) | 0.539 |

| Median*, ‡, §, ‖ | 368 | 452 | |

*Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data

†Missing N: Intervention = 4 total (3 with no diabetic patients identified by claims), and 1 physician who submitted no data); and Control = 1 with no diabetic patients identified by claims

‡Count of visits over baseline year, 2007

§Patient level data aggregated to practice level and weights applied to adjust for volume of episodes at each practice

‖Limited to cardiovascular procedure type episodes only

Qualitative assessment of the amount of practice redesign received by practices revealed that most practices (78 %) received the maximum amount, while the other 22 % received some or very little support.

Clinical Quality Measured at the Physician Level

Of 11 Clinical Quality measures, only two had differential change over time by study condition that was significant at the 5 % level. I-physicians increased Hypertensive Blood Pressure control by 23 percentage points, whereas c-physicians reduced HBP control by roughly 2 percentage points over 2 years (i-physicians: 179 %, c-physicians: −83 % change, P = 0.02) (Table 2). I-physicians increased Breast Cancer screening by 3.5 percentage points, whereas c-physicians reduced Breast Cancer screening by 0.4 percentage points over 3 years (i-physicians: 9 %, c-physicians: −1 % change, P = 0.03).

Table 2.

Provider Level Clinical Quality Process and Outcome Measures

| Measures | Time 0 Mean Percentage (n)* | Time 1 Mean Percentage (n)* | Time 2 Mean Percentage (n)* | Difference from Time 0 to Time 2† | % Difference‖ | Change Over Time by Group P Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Screening | ||||||

| Intervention | 36.5 % (36) | 38.2 % (38) | 40.0 % (40) | +3.5 % | +9 % | 0.029 |

| Control | 38.6 % (24) | 38.3 % (24) | 38.2 % (24) | −0.4 % | −1 % | |

| Cardiovascular Lipid Screening | ||||||

| Intervention | 93.1 % (27) | 93.2 % (31) | 93.3 % (34) | +0.2 % | +0 % | 0.401 |

| Control | 95.1 % (18) | 93.5 % (19) | 91.6 % (20) | −3.5 % | −4 % | |

| Nephrology Screening | ||||||

| Intervention | 95.2 % (33) | 93.4 % (35) | 91.3 % (37) | −3.9 % | −4 % | 0.474 |

| Control | 93.3 % (23) | 92.3 % (23) | 91.2 % (23) | −2.1 % | −2 % | |

| Chlamydia Screening | ||||||

| Intervention | 40.8 % (30) | 48.3 % (35) | 55.7 % (35) | +14.9 % | +36 % | 0.323 |

| Control | 39.9 % (20) | 42.5 % (20) | 45.0 % (21) | +5.1 % | +13 % | |

| Diabetic Lipid Screening | ||||||

| Intervention | 92.3 % (33) | 91.5 % (35) | 90.7 % (37) | −1.6 % | −2 % | 0.757 |

| Control | 93.1 % (23) | 91.9 % (23) | 90.5 % (23) | −2.6 % | −3 % | |

| Diabetic HbA1C Screening | ||||||

| Intervention | 87.7 % (33) | 86.8 % (35) | 85.8 % (37) | −1.9 % | −2 % | 0.957 |

| Control | 90.6 % (23) | 89.8 % (23) | 89.0 % (23) | −1.6 % | −2 % | |

| Hypertensive Blood Pressure Control§ | ||||||

| Intervention | – | 12.9 % (31) | 36.1 % (32) | +23.2 % | +179 % | 0.020 |

| Control | – | 2.3 % (21) | 0.4 % (20) | −1.9 % | −83 % | |

| Cardiovascular Lipid Control | ||||||

| Intervention | 55.1 % (26) | 56.2 % (30) | 57.2 % (32) | +2.1 % | +4 % | 0.127 |

| Control | 61.8 % (17) | 73.1 % (17) | 83.0 % (19) | +21.2 % | +34 % | |

| Diabetic Blood Pressure Control§ | ||||||

| Intervention | – | 3.2 % (35) | 5.9 % (37) | +2.7 % | +84 % | 0.385 |

| Control | – | 0.2 % (23) | 0.1 % (22) | −0.1 % | −50 % | |

| Diabetic Lipid Control | ||||||

| Intervention | 50.5 % (33) | 51.9 % (35) | 53.8 % (37) | +3.3 % | +7 % | 0.306 |

| Control | 52.1 % (19) | 57.5 % (23) | 62.9 % (22) | +10.8 % | +21 % | |

| Diabetic HbA1C Control | ||||||

| Intervention | 47.7 % (31) | 48.4 % (35) | 49.2 % (37) | +1.5 % | +3 % | 0.568 |

| Control | 47.1 % (19) | 49.0 % (23) | 50.1 % (23) | +3.0 % | +6 % | |

*Estimated mean from multilevel model coefficients

†Differential Clinical Quality score change from Baseline to 18-month follow-up between Intervention and Control groups

‡Time X group P Value; § Time 0 (2007) baseline data unavailable; Data reflects Time 1 and Time 2 periods only

‖Percent increase calculated as (Time 2 – Time 1)/Time 1; Percent decrease calculated as (Time 1 – Time 2)/Time 1

Efficiency at the Physician Level

Of ten efficiency measures, only one had a differential change over time by study condition that was significant at the 5 % level. I-physicians decreased ED visit count ratio by seven-tenths (0.7) of a percentage point, whereas c-physicians increased ED visit count ratio by half (0.5) of a percentage point over 3 years (i-physicians: −18 %, c-physicians: 10 % change, P = 0.002) (Table 3). This improvement resulted in a reduction of 3.8 ED visits per physician per year, which corresponds to savings of $1,900 per physician per year.

Table 3.

Provider Level Efficiency Measures

| Measures | Time 0 Mean Percentage (n)* | Time 1 Mean Percentage (n)* | Time 2 Mean Percentage (n)* | Difference from Time 0 to Time 2† | % Difference¶ | Change Over Time by Group P Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Efficiency Index | ||||||

| (All Episode Types) | ||||||

| Intervention | 14.3 % (37) | 12.5 % (39) | 11.0 % (39) | −3.3 % | −23 % | 0.069 |

| Control | 14.1 % (22) | 13.5 % (23) | 12.9 % (22) | +1.2 % | +9 % | |

| Hospital Adm. Efficiency Index | ||||||

| (All Episode Types) | ||||||

| Intervention | 3.3 % (36) | 3.7 % (35) | 4.1 % (34) | +0.8 % | +24 % | 0.212 |

| Control | 2.5 % (22) | 3.4 % (24) | 4.6 % (23) | +2.1 % | +84 % | |

| ED Efficiency Index | ||||||

| (Cardiovascular Episodes Only) | ||||||

| Intervention | 11.5 % (30) | 9.4 % (18) | 7.7 % (28) | −3.8 % | −33 % | 0.068 |

| Control | 8.9 % (21) | 9.3 % (10) | 9.8 % (20) | +0.9 % | +10 % | |

| Hospital Adm. Efficiency Index | ||||||

| (Cardiovascular Episodes Only) | ||||||

| Intervention | 3.2 % (28) | 3.2 % (27) | 3.1 % (24) | −0.1 % | −3 % | 0.109 |

| Control | 1.9 % (20) | 2.9 % (21) | 4.3 % (18) | +2.4 % | +126 % | |

| ED Visit Count Ratio | ||||||

| Intervention | 3.8 % (37) | 3.5 % (39) | 3.1 % (39) | −0.7 % | −18 % | 0.002 |

| Control | 5.1 % (22) | 5.3 % (24) | 5.6 % (23) | +0.5 % | +10 % | |

| Hospital Adm. Count Ratio | ||||||

| Intervention | 1.4 % (37) | 1.1 % (35) | 0.9 % (34) | −0.5 % | −36 % | 0.218 |

| Control | 1.8 % (22) | 1.7 % (24) | 1.5 % (23) | −0.3 % | −17 % | |

| Total Costs§ | ||||||

| Intervention | $33,854,512 (41) | $33,726,675 (42) | $33,599,081 (42) | −$255,431 | −0.7 % | 0.952 |

| Control | $39,106,708 (23) | $38,757,819 (24) | $38,410,494 (24) | −$696,214 | −1.8 % | |

| ED Costs | ||||||

| Intervention | $16,681 (37) | $18,570 (39) | $20,672 (39) | +$3,991 | +24 % | 0.214‖ |

| Control | $21,044 (22) | $25,659 (23) | $31,287 (23) | +10,243 | +49 % | |

| Hospital Adm. Costs | ||||||

| Intervention | $304,820 (36) | $279,346 (35) | $256,000 (34) | −$48,820 | −16 % | 0.578 |

| Control | $276,396 (22) | $240,090 (24) | $208,553 (23) | −$67,843 | −24 % | |

| Outpatient Costs | ||||||

| Intervention | $16,981,528 (41) | $17,621,731 (42) | $18,273,780 (42) | +$1,292,252 | +8 % | 0.657 |

| Control | $20,228,713 (23) | $20,083,857 (24) | $19,939,522 (24) | −$289,191 | −1 % | |

*Estimated mean from multilevel model coefficients

†Differential Clinical Quality score change from Baseline to 18-month follow-up between Intervention and Control groups

‡Differential Slopes by Study Conditions P value

§Total Costs include Emergency Room, Hospital Admission, Outpatient, Medical Office, Prescription, Laboratory Costs

‖P = 0.000 change over time in ER costs for both Study Conditions

¶Percent increase calculated as (Time 2 – Time 1)/Time 1; Percent decrease calculated as (Time 1 – Time 2)/Time 1

In addition, two trends showed that i-physicians decreased the ED efficiency index (i.e., improved their efficiency) for all episode types by 3.3 percentage points, whereas c-physicians increased the ED efficiency index (i.e., reduced their efficiency) by 1.2 percentage points over 3 years (i-physicians: −23 %, c-physicians: 9 % change, P = 0.07). I-physicians also decreased the ED efficiency index (improved efficiency) for cardiovascular episode types by 3.8 percentage points, whereas c-physicians increased the ED efficiency index (reduced efficiency) by nine-tenths (0.9) of a percentage point over 3 years (i-physicians: −33 %, c-physicians: 10 % change, P = 0.07).

There was no cost savings observed on any cost-of-care measures, including total, ED, hospital admission or outpatient episodes over 3 years (Table 3). Both study conditions experienced a significant increase in ED costs over 3 years (36.5 % change, P < 0.00), though this change was not different by study condition.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms the small but growing evidence from rigorously designed and evaluated demonstrations that implementing features of the PCMH may result in limited but significant improvements in both efficiency and quality outcomes with proper incentives and support. Importantly, it confirms in a general adult population previous findings from earlier studies employing at least three PCMH characteristics, of significant reductions in ED visits among high-risk elderly randomized to home-based, interdisciplinary care including PCP, specialty care, and a care manager;9,10 significant increases in quality of both processes and outcomes of care among depressed elderly randomized to collaborative care including care management, PCP and a specialist;11 and trends in ED cost reductions seen among older patients at high risk of heavy use of health care services randomized to PCP-led team care with care management.6 It also increases confidence in reports of positive outcomes from demonstrations with design and evaluation limitations.33–35 In addition, our design, which included multiple elements needed to achieve full recognition of Physician Practice Connections®-Patient-Centered Medical Home™ 2008 (PPC®-PCMH™)14 status awarded by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), offers insight into change during and immediately following introduction of supports, and aligns with results of other large but non-interventional reports that change is real but modest.36

Physicians in intervention practices demonstrated real improvements in BP control among hypertensives and real reductions in ED visit rates relative to the episodes of care during the year. While seemingly modest (3.8 ED visits saved per year) compared to savings among high-risk elderly9,10 and in large integrated health systems,6 the savings are substantial when considered over a large number of physicians. For instance, if panels were similar in size and complexity across the 142,000 in-network physicians in EmblemHealth’s Group Health Incorporated (GHI) plan, a supported PCMH transition across all physicians would be expected to save $270 million each year from ED visit reductions alone.

We expect that patient outcomes, such as the increase in BP control among hypertensives, are related to the intervention through the embedded care managers working as part of the PCP-led team, using EHRs to identify complex EmblemHealth patients, such as those with hypertension, for targeted care and education. Additionally, care managers engaged in targeted contact with high frequency ED users, which contributed to the significant reduction in ED visits per episode of care among intervention physicians’ patients. We have previously reported that many control practices were able to obtain practice redesign advice and EHRs during the study, but to our knowledge, only intervention practices had access to embedded care managers.14

Despite these improvements, we did not observe significant cost savings, and ED costs continued to rise over time, even with the significant reduction in visits observed. We attribute this to the rising cost of ED visits reported by EmblemHealth and the relatively modest reduction in ED visits. While modest, the reduction in ED visits is promising, and if increased, the difference in costs seen between control and intervention sites may become significant.

In addition to our significant findings, we report trends that suggest significant change on some dimensions may take longer, but that physicians in intervention practices are beginning to bend the curve. The relative cost of ED visits across all illness episodes compared to their peers (p = 0.07) showed a trend toward lower costs among intervention physicians.

Despite these significant findings, we were unable to report significant improvements in other HEDIS quality measures, such as Chlamydia screening; diabetes HbA1C or LDL-C screening and control; diabetes nephropathy screening or blood pressure control; and CAD LDL-C screening and control. We cannot explore the reasons for this lack of improvement, due to our lack of access to identified patient data, or to information on disease severity by patient. Therefore, we can only report on physicians’ panels over time, and cannot assess likely improvement among those exposed to the care manager’s interventional activities over time. It is also possible that our ED visit ratio results would be different if we could adjust for disease severity. However, we know that practices were not different at baseline on anything other than outpatient volume, so we suspect no difference in the severity of the patient panels. In addition, because we do not have access to patient level data, we are unable to assess the degree to which the CPT-II data are representative of all patients (e.g., all hypertensives). Nor can we provide results that are relevant to general adult primary care in non-urban locations. Finally, we did not find differences in hospitalization rates, and were unable to conduct sub-analyses among sicker and/or older patients, where savings are more likely to be found.3,5,8,9

This paper provides important evidence that practice redesign and embedded care management in community-based practices using the PCMH model results in a modest but promising reduction in ED visits and improved quality of care. However, unanswered questions remain. Can this model be enhanced to obtain real cost savings without sacrificing quality? Perhaps adopting more targeted strategies aimed at short-term cost reductions, as described in highly efficient practices37 or in the Clinical Microsystems approach,38 would yield more impressive results. Is this approach “scalable” to many similar practices? This issue remains a challenge with no easy answers. Additional research that explores alternative approaches, such as a “public utility model”39 or “hovering,”40 that leverage shared local and remote services could solve many of the scalability barriers.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 24.2 kb)

(DOCX 60.5 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

The Commonwealth Fund supported the independent evaluation of this demonstration by the Ethel Donaghue Center for Translating Research into Practice and Policy (TRIPP Center) at the University of Connecticut Health Center from 1 December 2007 through 31 March 2010. EmblemHealth has provided continued evaluation support for the purposes of data analysis, 1 March 2011 through 31 May 2011 and 1 September 2011 to 31 December 2013. The full trial protocol can be accessed by contacting EmblemHealth.

Conflict of Interest

Judith Fifield, PhD, reports having received two honoraria from Zimmer in the last 3 years. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affair. 2008;27(3):759–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr MS. The need to test the patient-centered medical home. JAMA. 2008;300(7):834–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro J, Smith K, Parchman M, Meyers D. Early Evidence on the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Final Report. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012 Feb. Contract No.: HHSA290200900019I/HHSA29032002T and HHSA290200900019I/HHSA29032005T. Sponsored by: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- 4.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TW, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the geriatric resources for assessment and care of elders management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1420–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes SL, Weaver FM, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2877–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unützer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele GD, Haynes JA, Davis DE, et al. How Geisinger’s advanced medical home model argues the case for rapid-cycle innovation. Health Affair. 2010;29(11):2047–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bielaszka-DuVernay C. The ‘GRACE’ model: in-home assessments lead to better care for dual eligibles. Health Affair. 2011;30(3):431–4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomized trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):259–62. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorr DA, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Standards and Guidelines for Physician Practice Connections—Patient-Centered Medical Home Version. 2008 [cited 2013 February 4]. Available from: URL: http://www.usafp.org/PCMH-Files/NCQA-Files/PCMH_Overview_Apr01.pdf.

- 14.Fifield J, Dauser Forrest D, Martin-Peele M, Burleson JA, Goyzueta J, Fujimoto M, Gillespie W. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Implementing the Patient-Centered Medical Home Model in Solo and Small Practices. JGIM 2012; Online First 07 September 2012, doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2197-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bitton A, Martin C, Landon BE. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. JGIM. 2010;25(6):584–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol 1994; Suppl 12:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gawande A. Medical Report: the Hot Spotters. The New Yorker 2011 January 24 [cited 2013 February 4]. Available from: URL: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/01/24/110124fa_fact_gawande.

- 18.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Expanding “Hot spotting” to New Communities. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1 January 2012 [cited 2013 February 4]. Available from: URL: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/meetings_and_conferences/speeches_and_presentations/2012/rwjf72538.

- 19.National Committee for Quality Assurance (US). HEDIS 2009. Washington: Technical Specifications. 2008;2.

- 20.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Quality Compass 2012. Available at: URL: http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/177/Default.aspx. Accessed February 4, 2013.

- 21.Rosenthal MB, Abrams MK, Bitton A, Patient-Centered Medical Home Evaluators’ Collaborative. Recommended Core Measures for Evaluating the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Cost, Utilization, and Clinical Quality [data brief]. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2012 May. Publication No. 1601,12.

- 22.Meyers D, Peikes D, Dale S, Lundquist E, Genevro J. Improving Evaluations of the Medical Home. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011 Sept. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0091.

- 23.MEG—Medical Episode Grouper™ [manual] New York (NY): Thomson Healthcare; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyons K, Sayer A. Longitudinal dyad models in family research. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67(4):1048–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31(3):437–48. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnett R, Marshall N, Raudenbush S, Brennan R. Gender and the relationship between job experiences and psychological distress: a study of dual-earner couples. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(5):794–806. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raudenbush S, Brennan R, Barnett R. A multivariate hierarchical model for studying psychological change within married couples. J Fam Psychol. 1995;9(2):161–74. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.9.2.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheskin DJ. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures. 3. Boca Raton (FL): Chapman & Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5. Boston (MA): Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Congdon R. HLM 6 for Windows [computer program] Skokie (IL): Scientific Software International, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. 2. New York (NY): Routledge; 2010. pp. 233–56. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner BD, Denham AC, Ashkin E, Newton WP, Wroth T, Dobson LA. Community care of North Carolina: improving care through community health networks. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):361–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for physicians. Health Affair. 2010;29(5):835–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaen CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–60. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Fontaine P, Flottemesch TJ, Anderson LH. Trends in quality during medical home transformation. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(6):515–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milstein A, Gilbertson E. American medical home runs: four real-life examples of primary care practices that show a better way to substantial savings. Health Affair. 2009;28(5):1317–26. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Godfrey MM, editors. Quality by Design: A Clinical Microsystems Approach. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villagra VG. Accelerating the adoption of medical homes in connecticut: a chronic-care support system modeled after public utilities. Conn Med. 2012;76(3):173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asch DA, Muller RW, Volpp KG. Automated hovering in health care—watching the 5,000 hours. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):1–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1203869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24.2 kb)

(DOCX 60.5 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)