ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Despite a growing need for primary care physicians in the United States, the proportion of medical school graduates pursuing primary care careers has declined over the past decade.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the association of medical school research funding with graduates matching in family medicine residencies and practicing primary care.

DESIGN

Observational study of United States medical schools.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred twenty-one allopathic medical schools.

MAIN MEASURES

The primary outcomes included the proportion of each school’s graduates from 1999 to 2001 who were primary care physicians in 2008, and the proportion of each school’s graduates who entered family medicine residencies during 2007 through 2009. The 25 medical schools with the highest levels of research funding from the National Institutes of Health in 2010 were designated as “research-intensive.”

KEY RESULTS

Among research-intensive medical schools, the 16 private medical schools produced significantly fewer practicing primary care physicians (median 24.1 % vs. 33.4 %, p < 0.001) and fewer recent graduates matching in family medicine residencies (median 2.4 % vs. 6.2 %, p < 0.001) than the other 30 private schools. In contrast, the nine research-intensive public medical schools produced comparable proportions of graduates pursuing primary care careers (median 36.1 % vs. 36.3 %, p = 0.87) and matching in family medicine residencies (median 7.4 % vs. 10.0 %, p = 0.37) relative to the other 66 public medical schools.

CONCLUSIONS

To meet the health care needs of the US population, research-intensive private medical schools should play a more active role in promoting primary care careers for their students and graduates.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2286-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: primary care, medical education, research funding

Primary care physicians play a pivotal role in meeting the growing health care needs of the expanding and aging population of the United States. The majority of medical students entering residencies in internal medicine and pediatrics, however, eventually specialize in fields other than primary care that offer better compensation and perceptions of greater prestige. In 2003, only 27 % of third-year internal medicine residents expected to practice general internal medicine,1 and in 2007, only 2 % of graduating medical students planned careers in this field.2 Moreover, the proportion of graduates matching in family medicine residency programs has been declining over the past decade.3 Expanding medical schools to increase the total number of US medical graduates will not yield a greater proportion of new physicians entering primary care if medical students continue to opt for specialist careers. Furthermore, clinical leaders and educators are needed in academic primary care to train students who will become the next generation of primary care physicians.

“Research-intensive” medical schools receive the largest amounts of federal research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and play a central role in training future leaders in all clinical fields, including primary care. One recent study, however, found that graduates of the ten most research-focused medical schools were more likely to pursue specialties with higher incomes and more controllable lifestyles than graduates of other medical schools.4

The policies and cultures of U.S. medical schools are an important factor to consider in promoting primary care. Therefore, we assessed how the research intensity of medical schools was associated with their production of primary care physicians, and whether this association differed for private and public medical schools.

METHODS

Data Sources and Measures

To assess the extent to which recent graduates of research-intensive private and public medical schools pursue careers in primary care, we used the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool to determine the total amount of NIH research funding received by allopathic U.S. medical schools and their closely affiliated academic medical centers during 2010.5 NIH grants to affiliated schools of public health, dentistry, nursing, science and engineering and training grants were not included in these totals. We then ranked medical schools on this measure of NIH funding and designated the top 25 schools as the most research-intensive.

To determine the degree to which each medical school’s graduates pursue careers in primary care, we analyzed two outcome measures. First, from a published study, we determined the proportion of each school’s graduates from 1999 to 2001 who were listed in the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile as practicing primary care physicians in 2008.6 Second, from a report by the American Academy of Family Physicians, we obtained the average proportion of each school’s graduates who entered family medicine residencies during 2007 through 2009.3 We excluded four medical schools that lacked data on either of these measures (Florida State University, Rosalind Franklin University-Chicago Medical School, San Juan Bautista Medical School, and University of Toledo), yielding a study cohort of 121 medical schools.

The percentage of under-represented minorities graduating from each medical school from 1999 through 2001 was obtained from a previously published study.6 The presence of primary care residencies in internal medicine or pediatrics at each medical school’s major affiliated teaching hospitals in 2010 was obtained from the National Resident Matching Program.7 The presence of a family medicine department at each medical school was determined from a published report.3 For schools with a family medicine department, we determined from the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool whether these departments received any NIH research funding.5 From this NIH tool, we also tallied the number of unique principal investigators at each medical school to calculate the average level of NIH grant funding per principal investigator.

Because we used publicly available institutional data with no personal identifiers, our study was deemed not to be human research by the Human Studies Committee of Harvard Medical School.

Statistical Analysis

After ranking all 121 allopathic medical schools by their total amount of NIH research funding in 2010 (Appendix Table, available online), we compared the top 25 medical schools to the remaining 96 schools by their total proportion of graduates from 1999 to 2001 who were practicing in primary care in 2008, and by their average proportions of graduates who matched in family medicine from 2007 to 2009. We also stratified these comparisons for private and public medical schools in each group. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare differences in the two outcomes between groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between the proportions of graduates from 1999 through 2001 practicing primary care in 2008 and of graduates from 2007 through 2009 who matched in family medicine residencies.

We used generalized linear regression models to assess the adjusted association of research intensity with the proportion of each medical school’s graduates entering careers in primary care, as measured by the two outcome variables described above. The main version of these two models included dichotomous variables for the top 25 most research-intensive schools and for private schools, along with the interaction of these two variables. Building on these primary models, we conducted a series of secondary analyses to determine whether any of the following variables contributed to the associations of these predictors with the two main outcomes: 1) Average NIH funding per principal investigator; 2) Presence of a family medicine department; 3) Any NIH funding to a family medicine department; 3) Presence of any primary care residency positions in internal medicine or pediatrics; 4) Proportion of under-represented minority students.

We report two-tailed statistical tests for all analyses using SAS statistical software (Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

The 25 most research-intensive medical schools are shown in Table 1, along with their levels of NIH research funding in 2010 and their private or public status. Table 2 depicts the unadjusted outcomes and other study variables for all medical schools, stratified by research intensity and private or public status.

Table 1.

Primary Care Careers Among Recent Graduates of 25 Most Research-Intensive United States Medical Schools Based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Funding in 2010

| Medical School and Affiliated Academic Medical Centers | 2010 NIH Research Funding5 | Status | 1999–2001 Graduates Practicing Primary Care in 20086 | 2007–2009 Graduates Matching in Family Medicine Residencies3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harvard Medical School | $1,270,965,633 | Private | 22.7 % | 2.2 % |

| 2 | University of Pennsylvania | $479,480,704 | Private | 19.1 % | 2.7 % |

| 3 | Johns Hopkins University | $438,777,365 | Private | 24.3 % | 1.7 % |

| 4 | University of California, San Francisco | $422,075,871 | Public | 36.1 % | 5.1 % |

| 5 | Washington University in St. Louis | $365,408,802 | Private | 28.4 % | 0.5 % |

| 6 | University of Pittsburgh | $359,748,904 | Public | 37.2 % | 7.4 % |

| 7 | Yale University | $354,961,735 | Private | 29.3 % | 2.8 % |

| 8 | University of Michigan | $332,503,441 | Public | 31.5 % | 6.5 % |

| 9 | University of Washington | $326,882,613 | Public | 44.6 % | 12.5 % |

| 10 | Duke University | $305,653,535 | Private | 22.3 % | 2.0 % |

| 11 | University of California, San Diego | $304,658,066 | Public | 39.5 % | 9.3 % |

| 12 | Vanderbilt University | $296,277,355 | Private | 21.9 % | 1.0 % |

| 13 | University of California, Los Angeles | $294,323,006 | Public | 35.9 % | 7.1 % |

| 14 | Stanford University | $292,471,130 | Private | 27.4 % | 2.8 % |

| 15 | Cornell University | $257,170,990 | Private | 18.5 % | 1.7 % |

| 16 | University of North Carolina | $238,601,335 | Public | 32.4 % | 11.1 % |

| 17 | Columbia University | $235,320,298 | Private | 20.3 % | 1.4 % |

| 18 | Emory University | $226,961,115 | Private | 32.3 % | 2.5 % |

| 19 | Baylor College of Medicine | $213,937,825 | Private | 30.3 % | 5.6 % |

| 20 | Mayo Medical School | $197,792,276 | Private | 23.8 % | 8.5 % |

| 21 | Mount Sinai School of Medicine | $180,312,503 | Private | 26.0 % | 2.3 % |

| 22 | Oregon Health and Science University | $178,199,324 | Public | 43.8 % | 14.2 % |

| 23 | University of Chicago | $173,664,348 | Private | 22.6 % | 2.6 % |

| 24 | University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center | $170,252,955 | Public | 26.8 % | 6.0 % |

| 25 | University of Rochester | $167,774,604 | Private | 29.0 % | 5.3 % |

Table 2.

Characteristics of United States Medical Schools Stratified by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Funding and Private or Public Status

| Number of schools | All Schools | 25 Most Research-Intensive Medical Schools | 96 Other Medical Schools | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | Public | Private | Public | ||

| 121 | 16 | 9 | 30 | 66 | |

| Median proportion of 1999–2001 graduates in primary care in 2008 | 34.6 % | 24.1 % | 36.1 % | 33.4 % | 36.3 % |

| Median proportion of 2007–2009 graduates matching in family medicine residencies | 8.2 % | 2.4 % | 7.4 % | 6.2 % | 10.0 % |

| Median total NIH funding | $108.1M | $274.8M | $304.7M | $33.1M | $40.0M |

| Median NIH funding per principal investigator | $558,983 | $692,196 | $648,350 | $567,421 | $514,521 |

| Proportion with family medicine department | 91.7 % | 50.0 % | 100.0 % | 93.3 % | 100.0 % |

| Proportion with NIH-funded family medicine department | 38.0 % | 25.0 % | 77.8 % | 30.0 % | 39.4 % |

| Proportion with primary care residency positions | 22.3 % | 31.3 % | 33.3 % | 33.3 % | 13.6 % |

| Proportion of under-represented minority students | 10.7 % | 15.1 % | 13.5 % | 9.4 % | 10.7 % |

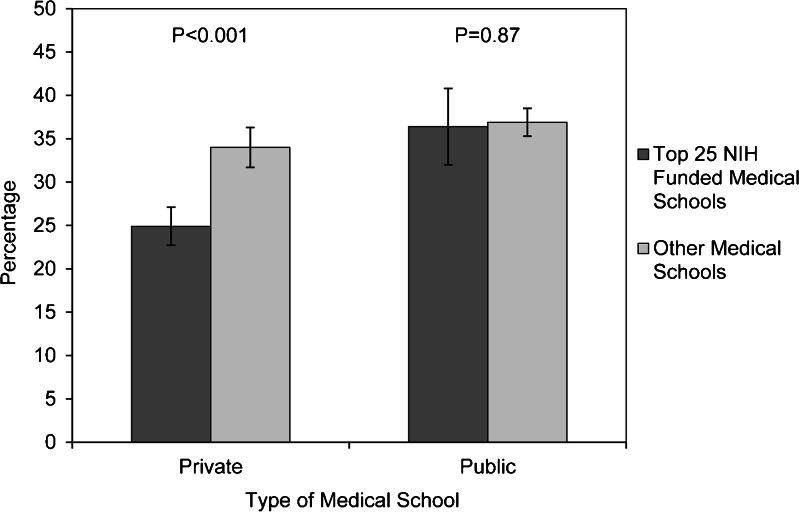

The 25 most research-intensive medical schools had significantly lower proportions of graduates practicing primary care (29 % vs. 36 %, p < 0.001) and matching in family medicine (5 % vs. 9 %, p < 0.001), compared to the other 96 less research-intensive medical schools. When stratified for private and public medical schools, these differences were evident only among private medical schools (Fig. 1). As shown in Table 2, the 16 private schools among the top 25 in NIH research funding had fewer graduates practicing primary care than the 30 other private schools (24.1 % vs. 33.4 %, p < 0.001) and fewer recent graduates matching in family medicine residencies (2.4 % vs. 6.2 %, p < 0.001). In contrast, no significant differences were seen between the nine most research-intensive public medical schools and the other 66 public medical schools in their proportions of graduates practicing primary care (median 36.1 % vs. 36.3 %, p = 0.87) or matching in family medicine residencies (median 7.4 % vs. 10.0 %, p = 0.37).

Figure 1.

Percentage of 1999–2001 graduates practicing primary care in 2008 by type of medical school. The “most research-intensive” schools are those ranked in the top 25 for research funding from the National Institutes of Health during 2010.5 The proportions of graduates during 1999 through 2001 practicing primary care in 2008 were ascertained from Mullan et al.6 Error bars represent 95 % confidence intervals of means.

In regression models assessing the proportion of graduates from 1999 through 2001 practicing primary care in 2008, the base model included variables for research-intensive schools, private schools, and the interaction of these two variables. Relative to less research-intensive public medical schools, research-intensive public medical schools did not differ significantly (-0.5 %, p = 0.82), but graduates were significantly less likely to be practicing primary care from research-intensive private schools (-8.6 %, p = 0.003) and other private schools (-2.9 %, p = 0.03). Similarly, the proportion of recent graduates matching in family practice residencies did not differ for research-intensive public schools (-1.2 %, p = 0.36) relative to other public schools, but tended to be lower in research-intensive private schools (-3.0 %, p = 0.08) and other private schools (-2.9 %, p < 0.001).

In secondary analyses, we added additional predictors shown in Table 2 to these base models, and the magnitude and statistical significance of the primary findings were largely unchanged (data not shown). Relative to schools in the lowest quartile of under-represented minority students, the proportions of graduates from 1999 through 2001 practicing primary care were significantly lower in the second quartile (-3.4 %, p = 0.03) and third quartile (-3.9 %, p = 0.01), but not in the highest quartile (-1.6 %, p = 0.33). The measures of NIH funding per principal investigator, presence of a family medicine department, NIH funding to family medicine departments, and the presence of primary care residency positions in internal medicine or pediatrics were not significant predictors of recent graduates practicing in primary care or entering family medicine residencies when added to either base model, respectively.

For most types of medical schools, we found that the proportion of graduates matching in family medicine residencies during 2007 through 2009 was highly correlated with the proportion of graduates from 1999 through 2001 who were primary care physicians. Significant correlations between these two outcome variables were noted for all schools (r = 0.73, p < 0.001), as well as for the 25 most research-intensive medical schools overall (r = 0.79, p < 0.001), the other 96 medical schools (r = 0.66, p < 0.001), and the nine most research-intensive public medical schools (r = 0.70, p = 0.04). The correlation was much lower and non-significant, however, for the 16 most research-intensive private medical schools (r = 0.26, p = 0.34).

DISCUSSION

Among US medical schools, we found that private, research-intensive schools were least likely to produce primary care physicians among their recent graduates. In contrast, public schools that receive similar levels of NIH funding have been able to maintain robust research portfolios, while producing primary care physicians at rates that are equivalent to other public and private medical schools with lower levels of NIH funding. Furthermore, our adjusted analysis suggests that private status and high levels of NIH funding are more strongly associated with the proportions of recent graduates entering primary care practice and family medicine residencies than other variables, such as the proportion of under-represented minority medical students or the presence of a family medicine department or primary care residency programs.

This study illustrates the potential value of improved monitoring of the career choices of medical school graduates. Given the high rates of specialization among graduates entering pediatrics and internal medicine, better tracking of primary care careers among graduates in these clinical fields would be useful to medical schools and policymakers.

The process of medical students selecting specialties is complex and multifaceted. Previous research has shown that demographic characteristics of medical students and their perceptions about primary care practice influence whether they will become primary care physicians. Demographic factors that have been associated with selection of a primary care career include female gender, lower socioeconomic status, older age, Latino ethnicity, rural background, non-traditional backgrounds, and plans for a primary care career at matriculation.8,9 However, with schools rather than individual students as the unit of analysis, our study did not find that the proportion of under-represented minority students was associated with primary care career choices.

Factors related to each medical school’s culture may play also play an important role in determining the number of graduates who enter primary care. Medical students and residents cite lower pay, lack of prestige, greater stress and bureaucracy, lack of technological emphasis and research opportunities, and perceptions of job dissatisfaction as deterrents to pursuing primary care careers.1,8,10 Positive and negative perceptions of primary care are shaped by students’ experiences during clinical rotations, interactions with faculty members, and the school’s culture or “hidden curriculum.”8 Research-intensive private medical schools are often able to attract very talented applicants from a wide range of racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. A lack of emphasis on careers in primary care at these schools may influence students initially interested in primary care to shift their focus to specialist careers.

The current fee-for-service system provides strong economic incentives for primary care physicians to maximize the number of patients they treat, which may decrease physician and patient satisfaction with the care delivered.11 Specialists are reimbursed at a much higher rate than primary care physicians, on average, leading to an income gap of $3.5 million over a career.12 Primary care reimbursement is being addressed through the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) enacted in 2010. The PPACA seeks to address these issues by increasing Medicare payments for primary care by 10 % from 2011 to 2015 and supporting innovative models of health care delivery and reimbursement.13 The PPACA also provides increased funding for the National Health Service Corps.14

Some initiatives have been implemented at research-intensive medical schools to promote primary care as a career choice for students. Many of these schools offer a combination of student-run clinics, primary care interest groups, loan-repayment programs, and certificate programs in urban and rural health that may stimulate and sustain students’ interest in primary care. Programs at two research-intensive medical schools—one public and one private—highlight approaches that such schools could pursue to increase their production of primary care physicians.

The University of Washington is a model for research-intensive medical schools to maintain a strong research portfolio while successfully training many students to become primary care physicians. This public medical school has demonstrated a strong focus on primary care through several programs to promote student interest in the field. Through the school’s agreements with Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and Alaska, students from these rural states receive in-state status as applicants and in-state tuition as students.15–17 The school’s Rural Integrated Training Experience, Targeted Rural and Underserved Track, Rural/Underserved Opportunities Program, and multi-state clerkship program provide students with hands-on clinical, research, and community service experiences in primary care ranging from 4 weeks to 4 years.18–20 These meaningful opportunities, coupled with relatively low in-state tuition and an admission policy that identifies and selects students likely to practice primary care, have enabled the University of Washington to produce the highest proportion of primary care physicians (44.6 %)6 among the 25 most research-intensive medical schools, while also maintaining the ninth-highest level of NIH research funding ($327 million in 2010).5

Harvard Medical School is a research-oriented private medical school that has recently devoted significant financial resources to advancing primary care through loan forgiveness programs and new educational programs and clinical innovations in its academic primary care practices. Financial aid programs have been in place since 2003 to ease the debt burden of students pursuing primary care.21 In 2011, the Center for Primary Care was launched with a $30 million donation.22 This center is supporting innovations in Harvard-affiliated primary care practices, and providing enhanced opportunities and resources for students to pursue careers in primary care. The center is promoting curricular changes to foster student interest in primary care, allocating funds for student-led primary care projects, and connecting students with faculty mentors in primary care. Providing these resources through a well-supported center is designed to give students greater support to pursue primary care careers. Further data will be needed to determine if these initiatives have a measurable impact on the career decisions of Harvard medical students. If successful, this center could provide a model for other research-intensive private medical schools to pursue similar initiatives.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, we used total NIH funding as the measure of research intensity. Although this figure does not account for research funding from other sources, total NIH funding provides a uniform, publicly available metric to compare research funding across all schools. In a secondary analysis, we assessed the average level of NIH research funding per principal investigator and the presence of NIH funding to family medicine departments, and we found no significant associations with either measure of schools’ output of primary care physicians. Second, the AMA Masterfile does not perfectly reflect the specialties of practicing physicians. However, previous studies have shown its accuracy ranges from 75 % to 90 % for physicians’ reporting general internal medicine or family medicine as their clinical specialty.23,24 Finally, our study demonstrates an association of greater NIH research funding with lower output of primary care physicians among research-intensive private medical schools, but this association is not necessarily causal, and may be due to other unmeasured factors that mediate this finding. For example, only seven of the 16 research-intensive private medical schools have departments of family medicine, whereas almost all other schools—including the nine most research-intensive public medical schools—have such departments.3 The presence of a family medicine department, however, was not a statistically significant predictor of graduates matching in family medicine residencies or practicing primary care.

To foster leaders in primary care, research-intensive private medical schools employ multiple approaches to promote primary care to students. Admission committees can strive to identify and recruit talented students with a strong interest in primary care. Primary care faculty can play a more prominent role as teachers and mentors for all students. Greater financial support can be provided to address the debt burden of students entering primary care who will have lower incomes after graduation than colleagues in other clinical fields. Most importantly, the leaders and faculties of research-intensive private medical schools can support primary care as a valued career choice for their graduates.

Our findings have important policy implications. Whereas research-intensive private medical schools produce relatively fewer primary care physicians, their research-intensive public counterparts have been able to maintain strong research programs while also producing higher proportions of primary care physicians. Private medical schools are generally not required to respond to public mandates, but they share a mission with all other medical schools to improve health. To achieve this mission, more physicians are needed who will become clinical leaders, teachers and innovators in primary care. By directing greater institutional resources and focus to train primary care leaders, research-intensive private medical schools can help to address the shortage of primary care physicians in the United States.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 54 kb)

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The authors are grateful to Lin Ding, PhD for assistance with statistical analyses, and to Debby Collins for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Funders

No grants or other internal or external financial support were received for the work presented in this manuscript.

Prior presentations

The content of this manuscript has not been presented at any conferences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garibaldi RA, Popkave C, Bylsma W. Career plans for trainees in internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2005;80:507–12. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200505000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students' career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1154–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGaha AL, Schmittling GT, DeVilbiss BAD, Crosley PW, Pugno PA. Entry of US medical school graduates into family medicine residencies: 2009–2010 and 3-year summary. Fam Med. 2010;42:540–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MS, Katz JT, Volpp KG. Match rates Into higher-income, controllable lifestyle specialties for students from highly ranked, research-based medical schools compared with other applicants. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:360–5. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00047.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools: Aggregate Data 2010. National Institutes of Health, 2010. Available at: http://report.nih.gov/. Accessed August 19, 2011.

- 6.Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:804–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Residency Matching Program. Program Results 2008-2012 Main Residency Match. 2012. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/data/resultsanddatasms2012.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 8.Bennett KL, Phillips JP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical bodel of specialty choice process. Acad Med. 2010;85:S81–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:502–12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compton MT, Frank E, Elon L, Carrera J. Changes in US medical students’ specialty interests over the course of medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1095–100. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T. Primary care — will It survive? New Engl J Med. 2006;355:861–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips RL, Dodoo JS, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce--What influences medical student and resident choices? Washington, DC: The Robert Graham Center; 2009. Available at: http://www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2009/rgcmo-specialty-geographic.Par.0001.File.tmp/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 13.Goodson JD. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: promise and peril for primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:742–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kocher R, Emanuel EJ, DeParle N-AM. The Affordable Care Act and the future of clinical medicine: the opportunities and challenges. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:536–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris TE, Coombs JB, House P, Moore S, Wenrich MD, Ramsey PG. Regional solutions to the physician workforce shortage: the WWAMI experience. Acad Med. 2006;81:857–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238105.96684.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz MR. The WAMI Program: 25 years later. Med Teach. 2004;26:211–4. doi: 10.1080/01421590410001696416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WWAMI Program. 2012. Available at: http://www.uwmedicine.org/education/wwami/pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 18.WRITE Program. 2012. Available at http://www.uwmedicine.org/education/md-program/current-students/curriculum/clinical-curriculum/write/pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 19.Targeted Rural and Underserved Track (TRUST). 2012. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/education/programs/trust. Accessed November 9, 2012

- 20.Rural/Underserved Opportunities Program (R/UOP. 2012. Available at http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/education/programs/trust. Accessed November 9, 2012

- 21.Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP). 2012. Available at: http://hms.harvard.edu/content/loan-repayment-assistance-program-lrap. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 22.A new Center for Primary Care. 2010. Available at: http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2010/10/hms-launches-center-for-primary-care/. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 23.Baldwin LM, Adamache W, Klabunde CN, Kenward K, Dahlman CL, Warren J. Linking physician characteristics and Medicare claims data: issues in data availability, quality, and measurement. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-82–95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shea JA, Kletke PR, Wozniak GD, Polsky D, Escarce JJ. Self-reported physician specialties and the primary care content of medical practice: a study of the AMA physician masterfile. American Medical Association. Med Care. 1999;37:333–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 54 kb)