Abstract

Background

First-line conservative treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women is behavioral intervention, including pelvic-floor muscle (PFM) exercise and bladder control strategies.

Objective

The purposes of this study were: (1) to describe adherence and barriers to exercise and bladder control strategy adherence and (2) to identify predictors of exercise adherence.

Design

This study was a planned secondary analysis of data from a multisite, randomized trial comparing intravaginal continence pessary, multicomponent behavioral therapy, and combined therapy in women with stress-predominant urinary incontinence (UI).

Methods

Data were analyzed from the groups who received behavioral intervention alone (n=146) or combined with continence pessary therapy (n=150). Adherence was measured during supervised treatment and at 3, 6, and 12 months post-randomization. Barriers to adherence were surveyed during treatment and at the 3-month time point. Regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of exercise adherence during supervised treatment and at the 3- and 12-month time points.

Results

During supervised treatment, ≥86% of the women exercised ≥5 days a week, and ≥80% performed at least 30 contractions on days they exercised. At 3, 6, and 12 months post-randomization, 95%, 88%, and 80% of women, respectively, indicated they were still performing PFM exercises. During supervised treatment and at 3 months post-randomization, ≥87% of the women reported using learned bladder control strategies to prevent SUI. In addition, the majority endorsed at least one barrier to PFM exercise, most commonly “trouble remembering to do exercises.” Predictors of exercise adherence changed over time. During supervised intervention, less frequent baseline UI and higher baseline 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) mental scores predicted exercise adherence. At 3 months post-randomization, women who dropped out of the study had weaker PFMs at baseline. At 12 months post-randomization, only “trouble remembering” was associated with exercise adherence.

Limitations

Adherence and barrier questionnaires were not validated.

Conclusions

Adherence to PFM exercises and bladder control strategies for SUI can be high and sustained over time. However, behavioral interventions to help women link exercise to environmental and behavioral cues may only be beneficial over the short term.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is defined as the complaint of involuntary urine leakage with physical effort or exertion, such as sneezing or coughing.1 Behavioral interventions, including pelvic-floor muscle (PFM) exercise and functional training in the use of these muscles to prevent urine loss, are recommended as first-line interventions for SUI. This recommendation is largely because PFM exercise is an effective, low-risk, and low-cost intervention for SUI.2 Imamura et al3 used economic modeling to compare costs and effectiveness of various management strategies for SUI. These investigators demonstrated that a clinical care pathway that included PFM exercise (lifestyle change followed by PFM, and then surgery, if necessary) was less costly and more effective than a pathway that did not include PFM exercise.3

Although short-term reduction in the frequency of incontinence episodes associated with behavioral interventions is high (up to 86% for women with SUI and mixed urinary continence [UI]),2,4–6 several long-term follow-up studies showed that many women decrease their adherence to PFM exercise over time.7–9 Barriers, or factors that interfere with PFM exercise adherence, may include poor exercise instruction from the provider; ambivalence regarding effectiveness; not knowing whether exercises were performed correctly; forgetting to exercise; lacking time, interest, self-motivation, or discipline to exercise; and interference of daily activities or other illnesses.10–14 Conversely, reasonable expectations and flexible recommendations for exercise, affirmation of correct exercise technique and symptom improvement, a desire to avoid surgery, and regular follow-up with a health care professional have been identified as factors that promote PFM exercise adherence.11,13

Potential predictors of PFM exercise adherence have identified demographic variables (higher age and education), general fitness level, severity of UI, and self-efficacy for PFM exercise.15–17 Knowledge of the impact of specific exercise-related barriers to PFM exercise adherence is more limited. One study demonstrated difficulty finding time to exercise as the only significant predictor of adherence in women with urgency-predominant UI 1 year following initial exercise instruction.18 Although evidence to enhance our understanding of PFM exercise adherence is growing, there is a void in our knowledge of factors that affect adherence to other components of behavioral intervention, specifically, the bladder control skills of using PFM contractions functionally to prevent SUI (known as the stress strategy19,20 or knack21) and urgency UI (known as the urgency suppression strategy19,22).

In addition, whether women are likely to adhere to PFM exercise when prescribed along with other UI interventions is not well understood. For instance, some women seeking conservative interventions for SUI also may be fitted with a continence pessary. Continence pessaries are believed to act by stabilizing the proximal urethra and urethrovesical junction, thus augmenting urethral closure and increasing urethral pressure to prevent SUI during occurrences of increased intra-abdominal pressure.23,24 Given the importance of cost-effective patient management, it is important to understand whether women will adhere to behavioral instruction while receiving another UI intervention such as the continence pessary.

This article reports on PFM exercise and bladder control strategy adherence data collected during the Ambulatory Treatments for Leakage Associated With Stress (ATLAS) incontinence study, a multisite, randomized controlled trial that compared 3 interventions for stress-predominant UI: intravaginal continence pessary, multicomponent behavioral therapy (including PFM training and bladder control strategies), and a combination of the 2 interventions.25 The aims of this planned secondary analysis were: (1) to describe rates of patient adherence to the behavioral therapy intervention, including PFM exercises and bladder control strategies; (2) to describe barriers to PFM exercise and bladder control strategy adherence as reported by the study participants; and (3) to identify predictors of PFM exercise adherence in women receiving PFM exercise alone or in combination with pessary therapy for SUI.

Method

Design Overview

The ATLAS study was a randomized clinical trial conducted by 9 clinical centers in the United States (see Appendix 2 for participating centers). Participants were women with SUI only or stress-predominant mixed UI. At each clinical center, the women were randomly assigned (stratified by UI severity [<14 versus ≥14 total UI episodes per 7-day bladder diary] and type) to receive an intravaginal continence pessary, a multicomponent behavioral intervention, or an intravaginal continence pessary combined with behavioral intervention. We selected this stratification cutoff based on a previous trial in which this cutoff resulted in good distribution of incontinence severity levels across treatment groups.26 Additional details of the study design and method have been described previously.25 Major findings of the ATLAS trial27 are briefly described here. Study outcomes were obtained by research staff blinded to group assignment. Three months after randomization, the primary study endpoint, women in the behavioral intervention and combined intervention groups reported significantly better symptom improvement (Patient Global Impression of Improvement Scale),28 a significantly higher proportion without “bothersome SUI symptoms” (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory),29 and significantly greater satisfaction (Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire)30 than participants in the pessary therapy group. Scores on all 3 of these measures for the combined group were similar and not superior to those of the behavioral intervention–only group. These group differences were not sustained when outcomes were compared 12 months post-randomization.27

Exercise and bladder control strategy adherence data were collected prospectively from the 2 groups of women who received the behavioral intervention, either alone or in combination with the intravaginal continence pessary. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating centers. All participants provided written informed consent.

Setting and Participants

Participants were community-dwelling women ≥18 years of age, recruited through the investigators' clinical practices, study announcements, advertisements, and referrals. Women were invited to participate in the study if they indicated symptoms of SUI on patient interview and documented SUI episodes in a 7-day bladder diary. Women with SUI only and stress-predominant mixed UI symptoms (number of SUI episodes exceeded urgency UI episodes) that had persisted for at least 3 months were considered for clinical evaluation. To be eligible for the study, women had to be at least 6 months postpartum, demonstrate a post-void residual volume <150 mL, and show 2 episodes of SUI in a 7-day baseline diary. They were excluded from participation if they reported continual urine leakage, previously participated in a supervised behavioral therapy or PFM training program for UI or fecal incontinence, were currently using a continence pessary or had used one within the previous 2 months, desired to become pregnant, or wanted to receive surgery for SUI within the next 12 months. Additional reasons for study exclusion were failed SUI surgery within the previous 3 months, presence of a vaginal foreign body (eg, exposed mesh or suture), severe atrophic vaginitis or current urinary tract infection, present use of medication for UI (imipramine and anticholinergics), or history of neurologic diseases known to affect bladder function (eg, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, stroke).

Interventions

Women in the multicomponent behavioral intervention–only and combined continence pessary and behavioral intervention groups attended 4 clinic visits at 2- to 3-week intervals such that all visits were completed within a maximum 10-week period. Participants in both groups kept a daily bladder diary throughout intervention. They also received a one-page handout that provided suggestions on optimal fluid intake (50–70 oz per day), constipation management (adequate fluid and fiber intake), measures to reduce urgency by spreading out fluid intake, avoiding caffeine and other potential bladder irritants, and the use of PFM contractions to control urgency.

The behavioral intervention was implemented by a licensed physical therapist, a certified registered nurse practitioner, or a registered nurse. To ensure standardized administration across clinicians and clinical sites, behavioral interventionists attended centralized training during which they trained to implement a standard protocol and were certified on patient education skills related to PFM exercise, bladder control strategies, and optimizing adherence.

Other means to standardize the behavioral intervention included use of encounter forms that required interventionists to check off each element of the behavioral intervention as it was completed and standardized patient education handouts. Interventionists attended bimonthly telephone conferences conducted by study coinvestigators to review study procedures, precept cases, and discuss any problems that arose during the trial.

The behavioral intervention included PFM exercises and bladder control strategies to prevent SUI19–21 and to diminish urgency, suppress bladder contractions, and prevent urgency incontinence for those with mixed UI.19,22 At the first behavioral intervention visit, each participant was instructed on how to correctly contract and relax her PFMs. The interventionist provided both verbal and tactile feedback using digital vaginal palpation during instruction. In addition, the interventionist observed for signs of Valsalva and counterproductive accessory muscle contraction. At each subsequent intervention visit, the interventionist used vaginal palpation and observation to determine whether the participant was performing PFM exercises correctly and to remediate any skill deficits. At each visit, the interventionist recorded whether or not (yes/no) the participant was able to perform 5 consecutive contractions without Valsalva or counterproductive accessory muscle contraction. However, the interventionist was not responsible for assigning a PFM strength score. Because PFM strength was a secondary study outcome, the clinical site outcome evaluator who was blinded to treatment assignment obtained this measurement at baseline and postintervention. Pelvic-floor muscle strength was determined through digital vaginal examination and quantified using the Brink scale.31 This scale includes the following 3 muscle function variables: muscle contraction duration, squeeze pressure felt around the examiner's fingers, and vertical displacement of the examiner's fingers as the woman contracts her PFMs. A 4-point categorical scale is used to rate each of these variables. The 3 scores are summed to obtain a composite score ranging from 3 to 12.31

Throughout the intervention phase, women were prescribed up to a maximum of 60 PFM contractions per day (performed over 2–3 exercise sessions per day). The maximum prescribed PFM contraction/relaxation duration was increased throughout the intervention phase from 3 seconds/6 seconds at visit 1 to a maximum of 10 seconds/20 seconds at visit 4. For each contraction, women were advised to contract (squeeze) their muscles “as hard as you can.” Women were initially taught to perform these exercises in a supine position, and they progressed to performing them while sitting and standing. The protocol allowed individualized exercise prescription at each visit. For example, women with very weak muscles could perform fewer or shorter-duration PFM contractions. Alternately, very active women with stronger muscles could perform all of their exercises in upright positions. The bladder control strategy for SUI consisted of instructing the woman to contract her PFMs just before and during activities that had provoked leakage. The bladder control strategy for urge UI consisted of instructions to not rush to the bathroom in response to the sensation of urge, but instead to remain still, repeatedly contract the PFMs, and wait for the urge to subside before walking to the bathroom at a normal pace.

Adherence to exercise and bladder control strategies was assessed, discussed, and recorded at each visit, and interventionists provided advice to minimize barriers and enhance adherence. For example, possible solutions to “forgetting to exercise” included posting a reminder note on a bathroom mirror or computer screen, setting aside a consistent time for exercise each day, or associating exercise with another established behavior such as brushing her teeth. When a woman failed to remember to squeeze her PFMs prior to a situation that would likely cause a stress UI episode (the stress strategy), she was advised to squeeze these muscles as soon as she felt the leakage to help develop the habit of remembering to squeeze proactively the next time.

Three months after randomization, the women were re-examined by the interventionist and provided with a maintenance exercise program of 15 PFM contractions per day at the maximum contraction duration achieved during the intervention phase. Our rationale for lowering the number of PFM contractions during maintenance exercise was twofold. First, success in preventing SUI episodes using the stress strategy may be more dependent on timing of muscle contraction than on muscle strength.32 Second, the number of muscle contractions needed to maintain a skill is unknown.33 We hypothesized that continued voluntary use of the stress strategy (knack) each day may replace the need to perform a high number of exercises following formalized intervention.

The women did not meet with the interventionist or receive any additional exercise instruction after the 3-month post-randomization visit. Study personnel other than the study outcome evaluator reviewed the 6- and 12-month post-randomization adherence questionnaires for completeness. This review was necessary to keep the study outcome evaluator blinded to group assignment.

Women in the combined intervention group also were fitted at their initial visit with a continence pessary (either a continence ring or dish) by a physician or nurse. They were taught how to insert and remove the pessary and encouraged to do so at least once per week. These women were seen 1 to 2 weeks later to ensure that the pessary was properly fitted and that there was no evidence of vaginal erosion or infection. If, after a third visit, a successful pessary fitting was not achieved, the pessary was removed, and women were advised to continue with the behavioral components of their intervention.

Adherence Outcomes

Adherence to PFM exercise and bladder control strategies was measured using self-administered questionnaires designed for this study. These questionnaires did not undergo psychometric testing. Face validity was supported by modeling questions related to exercise-specific barriers to adherence after those described by Sluijs et al34 and by review with the protocol investigators. Adherence and barrier questions asked throughout the study are listed in eTable 1. Because exercise barrier questions were used by the interventionist to adjust the PFM exercise program and to resolve issues related to adherence, these questions were asked only during supervised treatment visits and at the 3-month post-randomization visit.

Data Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the 2 groups were compared using Mantel-Haenszel tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA), adjusting for the 2 randomization stratification factors: incontinence frequency and incontinence type. Adherence to the behavioral program and barriers to exercise adherence were characterized using descriptive statistics.

For the analyses of adherence outcomes during the supervised intervention period, participants were grouped into 2 categories: adherent or not adherent. Our definition of adherence during supervised intervention was based partially on the exercise dose used in the study by Goode et al6 (15 contractions, 3 times per day), which showed an 80% overall reduction in urine leakage in women with stress UI or stress-predominate mixed UI.6 We also took into consideration the American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines for Progressive Strength Training, which recommend a similar muscle load and volume, but lower exercise frequency.35

Based on these sources, we arrived at a definition of adherence that we expected would increase muscle strength and produce a desirable reduction in UI. A participant was considered adherent during supervised intervention if she attended at least 3 of the 4 treatment visits and the average of her contractions per day and days per week exercised from visit 2 to visit 4 reported on exercise questionnaires was at least 30 contractions per day and at least 5 days per week, respectively. Otherwise, she was considered not adherent. At the 3- and 12-month post-randomization visits, participants were grouped into 3 categories: dropout, adherent, or not adherent. Because studies have shown that less frequent exercise is needed to maintain muscle strength than to increase muscle strength,35,36 we considered a woman adherent to the program if she reported doing her exercises at least 3 days per week and at least 15 contractions per day (the prescribed number of contractions). The number of days per week was calculated from the reported number of days per month exercised using the following formula: (days/month÷(365.25 days÷12 months)) × 7 days.

Potential predictors of adherence during supervised intervention included age, race, education level, employment status, caffeine intake, alcohol intake, frequency of UI, type of UI, number of people in the household, overall health-related quality of life (36-Item Short-Form Health Survey [SF-36] scores37), overall health status (Health Utility Index scores38), UI severity (Incontinence Severity Index scores39), PFM function (Brink scores31), and the physician's evaluation (yes/no) of whether the participant would be likely to benefit from these conservative interventions. All of these measurements were obtained at the baseline examination or prior to randomization. Potential predictors of long-term adherence (3 and 12 months post-randomization) included these same variables plus treatment modality, exercise barriers reported during supervised intervention and at the 3-month post-randomization visit (including the presence of any exercise barrier, total number of reported barriers, and presence of each specific barrier), and the mean number of contractions per week performed during intervention.

Potential predictors were first explored in bivariate analyses (Fisher exact test for categorical variables and ANOVA or t test for continuous variables) to determine their relationship to exercise adherence. Separate analyses were performed for the 3 outcome periods: supervised intervention, 3 months post-randomization, and 12 months post-randomization). Variables significantly related in bivariate analyses (with significance level set a priori at α=.10) were entered into multivariable regression models to test their independent association with adherence. A P value of <.05 in the multivariable analysis was considered significant.

Regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors that correlated with adherence versus nonadherence during supervised intervention and at 3 and 12 months post-randomization. For the supervised intervention period multivariable analysis, a logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with adherence (yes/no). For the 3-month and 12-month analyses, a multinomial regression model was used to identify predictors of adherence (adherent/not adherent/dropout). Because participants who attended fewer training sessions tended to report fewer barriers, in order to avoid bias in the 3- and 12- month post-randomization analyses, we included only participants who had attended ≥3 treatment visits.

Results

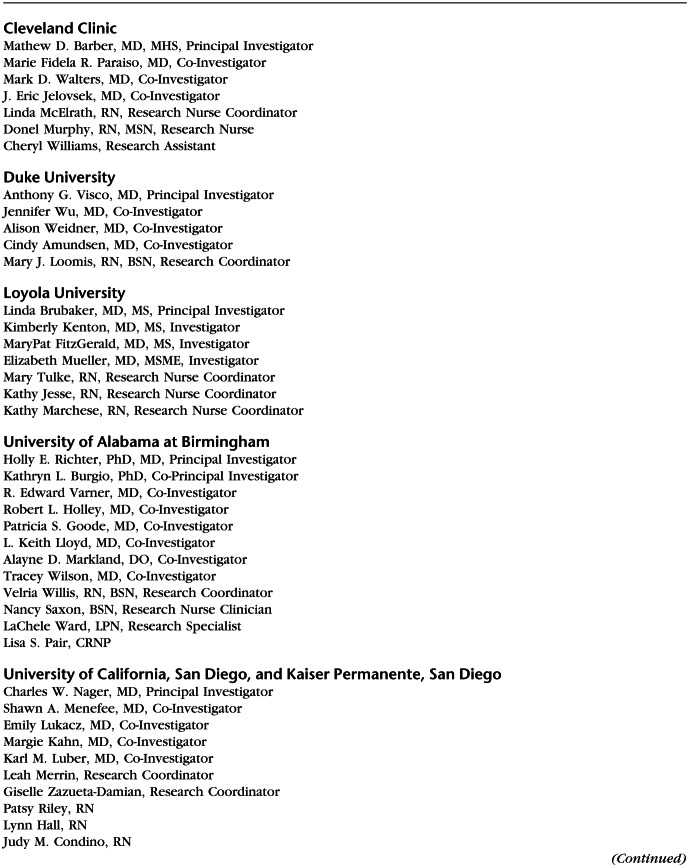

Between May 2005 and October 2007, 296 women were randomly assigned to the combined behavioral/pessary intervention group (n=150) or the behavioral intervention–only group (n=146). At baseline, demographic and medical characteristics were similar between groups (P>.05; Tab. 1). By 3 months after randomization, 18/150 (12%) of the women in the combined group and 22/146 (15%) of the women in the behavioral intervention–only group dropped out of the study. Dropout rates between the groups were not statistically different (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistic; P=.59).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants at Baseline by Intervention Group

At the initial intervention visit, 145/149 (97%) of the women in the combined group and 136/141 (96%) of the women in the behavioral intervention–only group demonstrated the ability to contract their PFMs without performing a Valsalva maneuver or contracting accessory muscles. At this visit, 100% of the women in the combined group (n=149) and 140/141 (99%) of the women in the behavioral intervention–only group indicated they were willing to perform the prescribed exercise program. Among the women still in the study at 3 months post-randomization, the proportion who indicated willingness to exercise was essentially unchanged in each group (combined group=124/126 [98%]; behavioral intervention–only group=118/119 [99%]).

Adherence to Behavioral Interventions

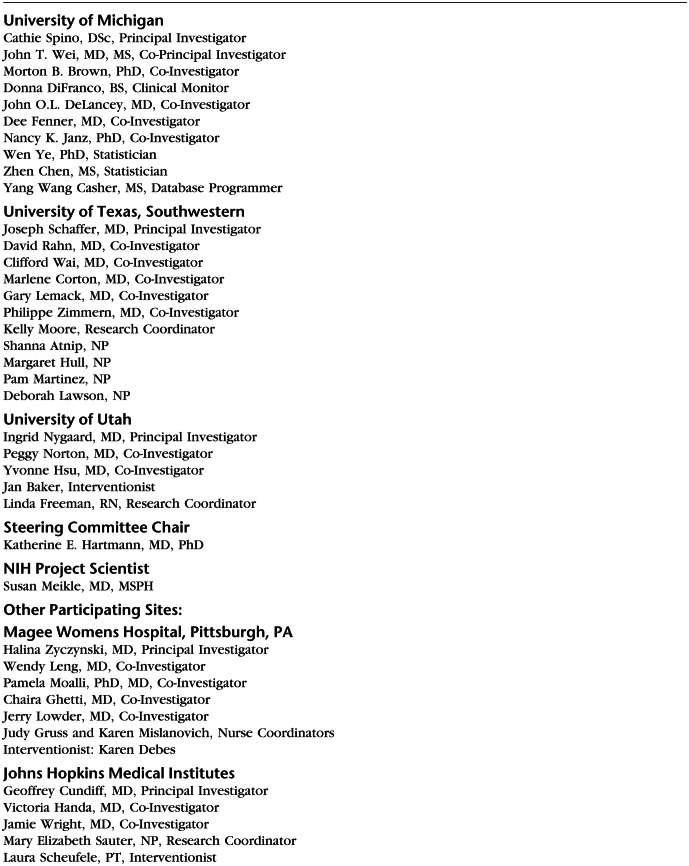

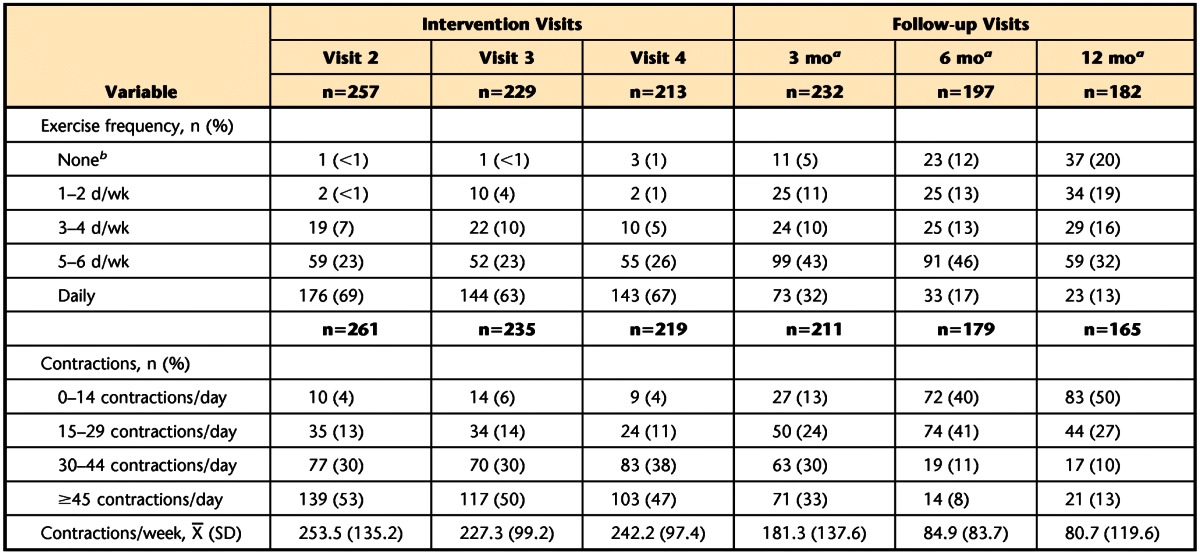

During supervised intervention and at 3 and 12 months post-randomization, the proportion of women who were adherent to the exercise program was not significantly different between the combined and behavioral intervention–only groups (Tab. 2). Therefore, we collapsed data across groups to analyze and present data on change in exercise frequency and number of exercises performed per day. Table 3 shows that across the supervised intervention period, the number of women who returned for visits decreased. However, among those who returned, the percentage who exercised 5 to 6 days per week remained high. Likewise, the proportion of women who performed ≥30 contractions per day remained high (>80%).

Table 2.

Number (%) of Women Adherent to Behavioral Intervention by Treatment Group During Supervised Intervention and at Follow-up

a Adherent during supervised intervention period=attended at least 3 treatment visits and performed, on average, 30 contractions per day at least 5 days per week. Adherent at 3- and 12-month follow-up visits=performed, on average, 15 contractions per day at least 3 days per week.

Table 3.

Exercise Frequency and Number of Exercises Performed per Day

a Time from randomization.

b No exercise during training visits and <0.5 d/wk for follow-up visits.

At 3, 6, and 12 months post-randomization, 95%, 88%, and 80%, respectively, of the women who continued to participate in the study were still performing PFM exercises (Tab. 3). By 12 months post-randomization, 61% of the women met the exercise frequency criteria for adherence, exercising at least 3 days per week. When women exercised, however, 50% performed fewer than the actual prescribed number (15) of PFM exercises. Of the remaining 50% of women, 23% performed well above the prescribed number of PFM contractions.

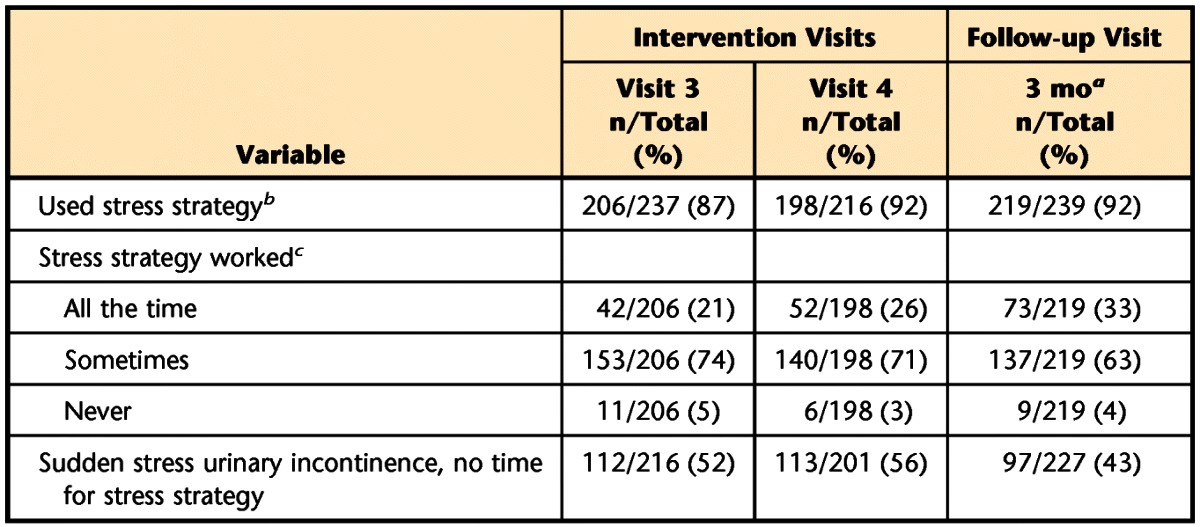

Table 4 presents data regarding the women's use of the stress strategy during supervised intervention and at the 3-month post-randomization visit. Ninety-five percent of the women were taught the stress strategy (ie, contract the PFMs prior to a situation that leads to SUI). Across time, ≥87% of the women who returned for the intervention visits reported using the stress strategy to prevent urine loss. The majority reported that the strategy worked “sometimes,” but the proportion of women for whom the strategy worked “all the time” increased from the 4-week intervention visit (visit 3) to the 3-month post-randomization endpoint. In addition, fewer women indicated that SUI occurred too quickly for them to apply the stress strategy (Tab. 4).

Table 4.

Use of Stress Strategies Across Time

a Time after randomization.

b 268 (95%) of the 296 randomized women who attended visit 2 were taught the stress strategy.

c Among those women who used the stress strategy.

Barriers to Exercise Adherence

The proportion of women who endorsed each exercise barrier during supervised treatment and at 3 months post-randomization is shown in eTable 2. For both groups, trouble remembering to exercise was the most frequently endorsed exercise barrier.

Across time, 62% to 72% of the women in the behavioral intervention–only group and 67% to 79% of the women in the combined group endorsed at least one exercise barrier. “Other” barriers reported across intervention groups included illness (self/family), vacation/travel, fatigue, work, personal conflicts, and boredom with exercise (eTab. 2).

Factors Associated With Exercise Adherence

During supervised treatment, baseline UI frequency and SF-36 mental scores were the only factors significantly associated with exercise adherence in the bivariate analyses. A higher proportion of women with less frequent UI (<14 UI episodes per week) compared with more frequent UI (≥14 UI episodes per week) were adherent to exercise recommendations (72% versus 59%, P=.02). Women who were adherent to recommendations also had slightly higher generalized quality of life as measured by mean (±SD) SF-36 mental scores compared with those who were not adherent (50.8±8.8 versus 47.3±9.8, P=.02). In the logistic regression model that included both UI frequency and SF-36 mental scores, both variables were significantly associated with adherence. The odds ratio (OR) for being adherent was 1.83 (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.11, 3.04; P=.02) for those who had lower UI frequency. A 1-unit increase in SF-36 mental scores was associated with OR=1.04 (95% CI=1.01, 1.07; P=.004) for being adherent.

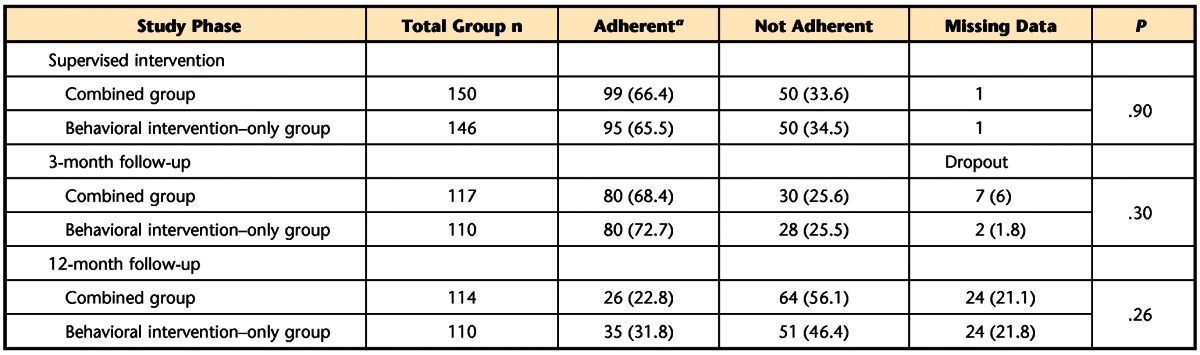

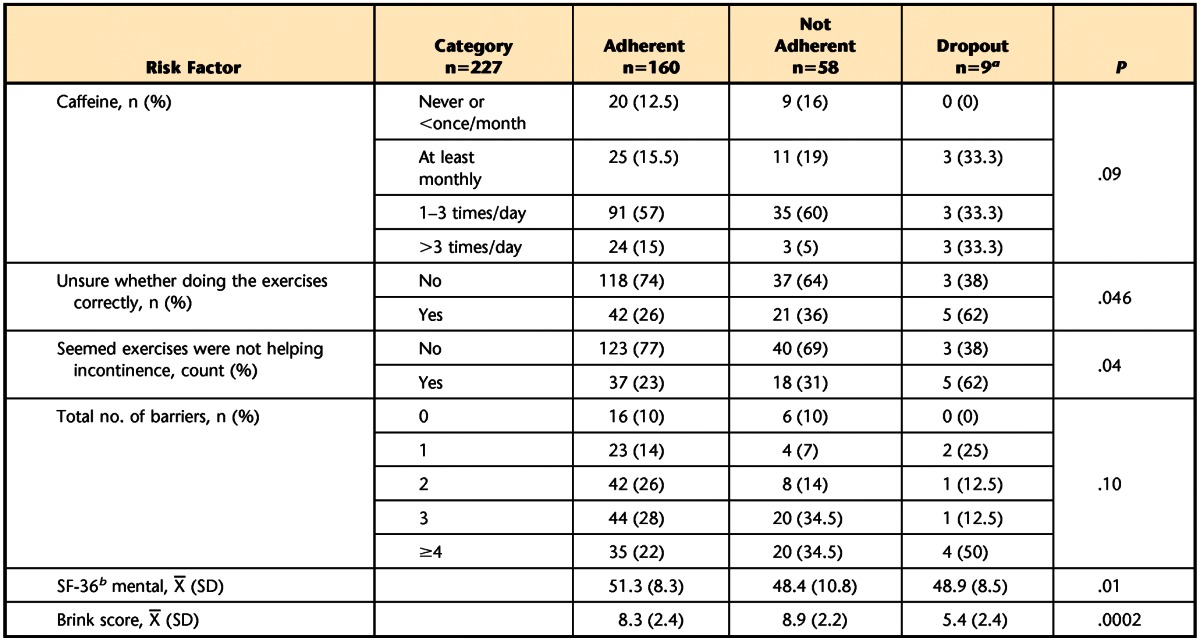

At 3 months post-randomization, the bivariate analyses identified differences between women who did and did not adhere to exercise recommendations or dropped out of the study with respect to baseline caffeine intake, SF-36 mental scores, and PFM strength (Brink score), as well as the total number of reported barriers to exercise, endorsement of the barrier “not sure if doing exercises correctly,” and endorsement of the barrier “seems exercise not helping incontinence” (P<.10; Tab. 5). In the multinomial model, which included these variables, baseline PFM strength (Brink score) was the only variable significantly related to adherence at 3 months post-randomization (P=.002). Women with weaker PFM muscles (lower Brink scores) at baseline were more likely (OR [dropout versus adherent]=2.1; 95% CI=1.26, 3.39) to drop out of the study.

Table 5.

Predictors Associated With Adherence to Treatment at 3 Months in Bivariate Analyses (P<.10)

a One woman in this category did not answer any of the exercise barrier questions; n=8 used to calculate means.

b SF-36=36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire.

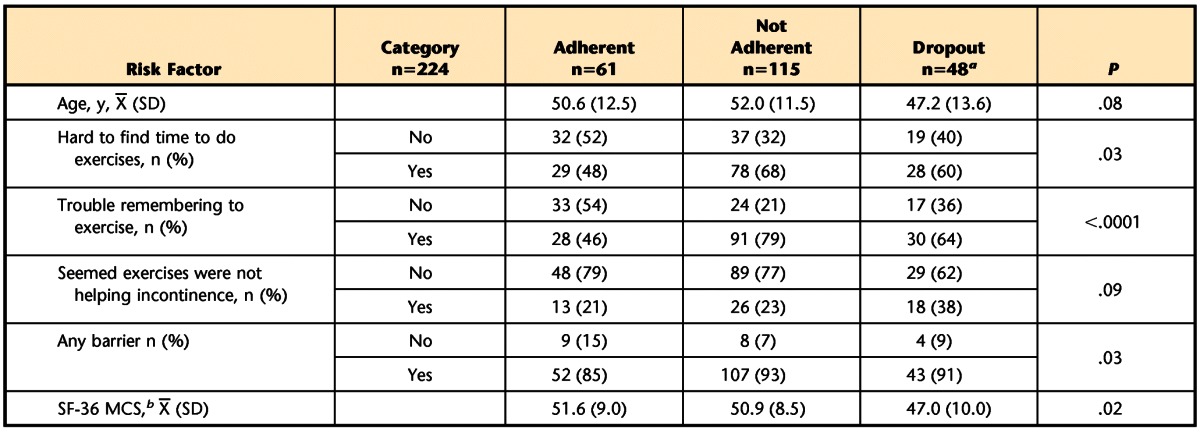

At 12 months post-randomization, the bivariate analyses identified differences between women who did and did not adhere to exercise recommendation or dropped out of the study with respect to age and baseline SF-36 mental scores, presence of any barrier to exercise, and endorsement of the barriers “hard to find time to exercise,” “having trouble remembering to do exercises,” and “seems exercise not helping incontinence” (P<.10; Tab. 6). In the multinomial analysis, which included these variables, only the barrier “having trouble remembering to do exercises” was significantly related to exercise adherence at 12 months (P=.001). Women who endorsed this barrier were significantly less likely to adhere to exercise recommendations (OR [adherent versus not adherent]=0.20, 95% CI=0.09, 0.48), but not significantly more likely to drop out of the study (OR [dropout versus adherent]=2.28; 95% CI=0.83, 6.3).

Table 6.

Predictors Associated With Adherence to Treatment at 12 Months in Bivariate Analyses (P<.10)

a One woman in this category did not answer any of the exercise barrier questions; n=47 used to calculate means.

b SF-36 MCS=36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire Mental Component Score.

Discussion

This study showed that during supervised intervention, exercise adherence was high for women with stress-predominant UI who received multicomponent behavioral intervention alone or in combination with a continence pessary. During this period, ≥86% of women exercised at least 5 days per week, and ≥80% performed at least 30 contractions per day on the days they exercised. These exercise rates are similar to those previously reported for women who underwent supervised behavioral intervention for stress UI40 or for urgency-predominant UI.18

Over the follow-up periods, ≥80% of women were still exercising their PFMs to some degree. By 12 months, approximately 50% of the women were exercising at least 5 days per week and performing at least the prescribed 15 contractions per day. This frequency of exercise was higher than the previously reported 33% of women with urgency-predominant UI who were still doing their exercises at least 5 days per week at 12 months. However, when these women exercised, the number of contractions they performed was similar (about 50% performed at least the prescribed 15 PFM contractions).18 In a prevention study including women who were postmenopausal, Hines et al41 reported a similar rate (67.4%) for women who exercised >2 to 3 times per week at 12 months. However, their rate for daily PFM exercise (34.8%) were higher than that observed in our study.41

As was the case during supervised intervention, long-term exercise rates did not differ between women who received the behavioral intervention alone or in combination with the continence pessary. Because PFM exercise generally declines over time, we might expect this trend to be greater for women using the continence pessary. Instead, we found only a small percentage of women relied on the continence pessary alone over the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up periods (2.5%, 5.9%, and 6.7%, respectively). Also, at 12 months, more women in this combined therapy group reported adherence to exercise only (50%) than adherence to both exercise and pessary therapy (30%). Based on these data, it appears that women with SUI felt that PFM exercise was important even when prescribed another UI intervention, the continence pessary.

At 3 months post-randomization, 92% of the women were using the stress strategy to prevent SUI episodes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document postintervention adherence to the stress strategy. Bø et al9 surveyed women 15 years after they received PFM training for SUI and inquired about whether they used the stress strategy to prevent UI. However, their study protocol did not include teaching the stress strategy as part of treatment. These investigators found that approximately one fourth of the women reported contracting their PFMs before coughing and sneezing.9 Miller and colleagues21 published on the short-term effectiveness of teaching the stress strategy without a muscle strengthening program. After 1 week of instruction, 80% and 94% of women with SUI were able to reduce urine loss associated with a medium and deep cough, respectively.21 Our study showed this strategy to be effective longer term. At 3 months post-randomization, 95% of the women who used the strategy reported that it was effective at least “sometimes,” and 21% reported that it worked “all the time.”

Predictors of exercise adherence changed over time in this study. Among the many variables that were examined, lower baseline UI frequency (<14 UI episodes per week) and higher levels of self-reported mental health (higher SF-36 mental scores) predicted exercise adherence during supervised intervention. At 3 months, lower baseline Brink scores (weaker PFMs) were the only statistically significant predictor of PFM exercise adherence. At 12 months post-randomization, the barrier “having trouble remembering to do exercises” was found as the only statistically significant predictor of PFM exercise adherence.

The observed transition in importance of variables from supervised intervention to long-term follow-up is consistent with the transtheoretical model of behavioral change.42 This model suggests that behavioral change occurs across a continuum from precontemplation to contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance43 and suggests that individuals will vary in their progression through these stages based on cognitive and performance factors. Additionally, the process of change is believed to vary across these stages.44 Therefore, whatever factors influence an individual's initial interest in and dedication to an intervention may no longer be adequate to sustain long-term adherence. For example, Alewijinse et al45 found that women's intention to adhere to PFM exercise measured prior to a course of physical therapy did not predict their long-term adherence to exercise 1 year later.

The finding that less frequent UI episodes was predictive of exercise adherence during supervised intervention differs from previous reports. Chen and Tzeng16 found that greater severity of UI (based on both UI frequency and amount of urine loss) predicted PFM exercise adherence in women with UI who underwent at least 6 weeks of exercise. This discrepancy might be partially explained by the differences in study participants. Our study included women with SUI only and stress-predominant mixed UI. The study by Chen and Tzeng included women with SUI, urgency UI, and mixed UI, and they did not report whether those women with mixed UI had predominantly stress versus urgency symptoms. Women with urge- or urgency-predominant symptoms typically experience greater volume of urine loss with each leakage episode compared with women with SUI. Thus, it is possible that symptom severity may influence adherence to PFM exercise differently in women with SUI versus urgency-predominant UI.

Another difference between the studies was the measure of exercise adherence. Chen and Tzeng16 used a 3-item adherence scale that included a rating of the average daily time spent on PFM exercise, the number of daily exercise repetitions performed, and a rating on a visual analog scale from 0 (“not at all adherent”) to 100 (“completely adherent”). In our study, to be categorized as adherent during intervention, women had to attend at least 3 treatment visits and, on average, perform 30 PFM contractions per day at least 5 days per week. Women who dropped out of our study during supervised intervention were included in the data analysis and classified as not adherent. Thus, if the women who dropped out of our study had a high UI frequency, it could explain why we found poorer adherence among women with more frequent UI.

Finally, although it is intuitive that women would be motivated by having more severe symptoms, their progress during supervised therapy also may have an impact on their adherence. Some studies have shown that women with milder SUI symptoms obtain better outcomes with behavioral treatment compared with those with more severe symptoms.46–48 During supervised treatment, noticeable symptom improvement can function as a positive reinforcer and may override the importance of symptom severity as a motivator for exercise adherence.

Our study also demonstrated that women with higher baseline SF-36 mental scores were more likely to be adherent than those with lower scores. Based on this finding, we would expect women with higher levels of psychological distress to have poor adherence and outcomes following a behavioral intervention for SUI. However, data regarding this premise are conflicting. Hendriks et al49 reported psychological distress as one of several prognostic indicators associated with poor short-term outcomes following physical therapy intervention in women with SUI. However, Burgio et al48 did not find an association between baseline psychological distress and successful behavioral treatment in women with either predominately urge UI or predominately SUI.

At the 3-month follow-up, baseline PFM strength emerged as the only predictor of exercise adherence. During supervised intervention, interventionists monitored women's ability to contract their PFMs and provided feedback about their progress. In a behavioral model, the goal is for the interventionist to encourage and motivate women in the early stages of treatment until their sense of control and success becomes its own positive feedback and sustains behavior change. It may be that women with stronger muscles experienced a stronger sense of control over their muscles and their leakage and attributed this control to their exercises, leading to sustained adherence. Conversely, women with weaker muscles may have had less proprioceptive feedback from PFM contraction or lower sense of efficacy, giving them less reason to sustain their efforts when they were no longer seeing the interventionist. Other investigators also have shown muscle weakness to interfere with long-term exercise.50,51 Clinically, these findings suggest that women with weak muscles should spend more time in initial supervised therapy. Alternatively, they might be followed periodically to assess PFM control, modify their maintenance exercise program, and support adherence until it is more self-sustained.

At the 1-year follow-up, the most important predictor of PFM exercise adherence became “trouble remembering to exercise.” Difficulty remembering to exercise also was found to be an important predictor of long-term PFM exercise adherence in women with urgency-predominant UI.18 In both of these studies, demographic, disease, and physical factors did not predict long-term adherence. Instead, a perceived barrier to exercise emerged as an important predictor.

Clinically, these findings indicate that women were having difficulty integrating the exercise regimen into their daily lives, which has implications not only for the supervised intervention phase but especially for long-term maintenance of behavior change. Initially, patients may require help identifying physical cues, times of day, or daily activities that can be used to remind them to do their exercises. This help may take the form of a timer, a routine daily behavior (eg, brushing teeth, eating breakfast), or a cue in the environment (eg, reminder notes, passing a road sign on the way to work, a television program that is watched every day). When patients link their exercises to such cues, the new exercise habit can be integrated with daily activities and PFM exercise becomes more automatic or habitual. For example, Hines and colleagues41 found that women who performed their PFM exercises at routine times of the day had a 12-fold and 2.7-fold greater likelihood of achieving adherence during the initial 3 months of exercise and at the end of the first-year follow-up, respectively.

The strengths of this study include having several data collection points during supervised intervention and follow-up phases. The 12-month follow up allowed us to examine several phases of adherence, including a relatively long-term phase. The exercise questionnaire assessed frequency of exercise sessions and number of exercises, but also included questions related to adherence to bladder control strategies and their perceived effectiveness. The focus on measuring specific barriers to adherence is new as applied to the treatment of SUI. The number of participating sites and interventionists strengthens the generalizability of the results. However, because women seeking surgery for UI were excluded from this study, generalizability of our findings is limited to women who seek conservative interventions for SUI or mixed UI.

Our conclusions are limited by the outcome measures and diagnosis of continence type being based on patient self-report. Furthermore, the exercise questionnaire, including questions related to PFM exercise and bladder strategy adherence, and barriers to adherence, was not validated. The intent of the adherence questions was to assist the interventionist to individualize the behavioral intervention by reducing matters related to adherence. During the supervised visit and the 3-month post-randomization visit, the questionnaire was reviewed by the interventionist. Therefore, opportunity existed to ensure questionnaire completeness and to answer questions in the event that items may have been misunderstood. Regardless, additional work is needed to develop and validate a UI behavioral intervention adherence questionnaire. Another study limitation is the inability to blind participants and interventionists to treatment assignment. However, study outcomes were obtained by evaluators blinded to participant randomization group and adherence logs.

Conclusion

When PFM exercises and bladder control strategies for SUI are implemented by trained interventionists, adherence to both can be high and sustained over time. The majority of women experience one or more barriers to regular PFM exercise, with the most common being trouble remembering to exercise and difficulty finding time. There is little in the characterization of the patient that predicts how well she will adhere to an individualized program of practice and exercise, but trouble remembering appears to be associated with lower adherence 12 months after treatment. Behavioral treatment components used in this study to help women link exercise to environmental and behavioral cues may only be beneficial over the short term. There is a need to develop new behavioral interventions that will help women remember and find time to perform PFM exercises longer term.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Pelvic Floor Disorders Network

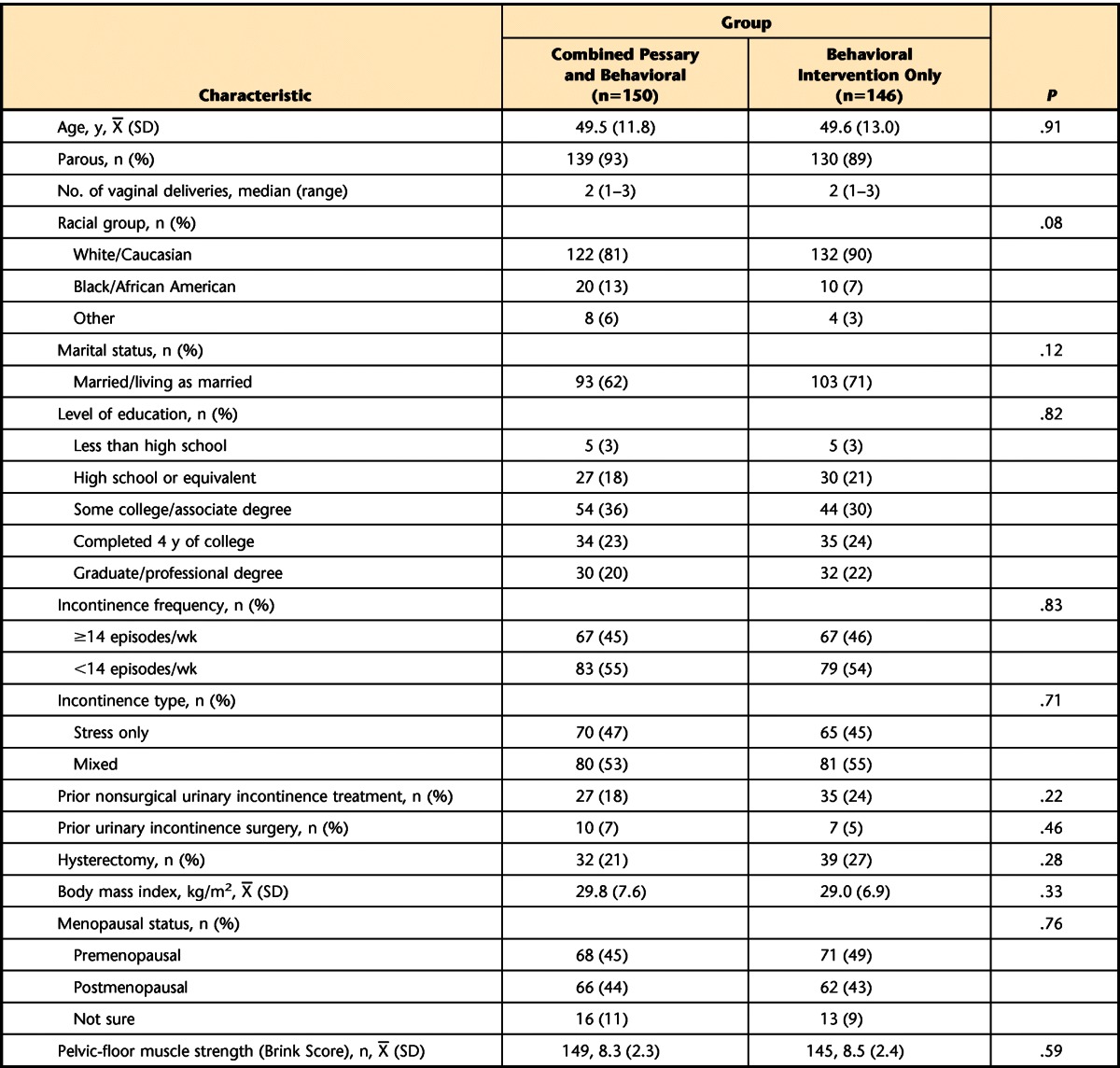

Appendix 2.

Appendix 2.

Participating Clinical Centers

Footnotes

Dr Borello-France, Dr Burgio, Dr Goode, Dr Bradley, Dr Schaffer, and Dr Kenton provided concept/idea/research design. Dr Borello-France, Dr Burgio, Dr Goode, Dr Ye, Dr Weidner, Dr Lukacz, Dr Jelovsek, Dr Bradley, Dr Hsu, Dr Kenton, and Dr Spino provided writing. Dr Lukacz, Dr Schaffer, Dr Hsu, and Dr Kenton provided data collection. Dr Borello-France, Dr Burgio, Dr Goode, Dr Ye, Dr Jelovsek, Dr Hsu, Dr Kenton, and Dr Spino provided data analysis. Dr Borello-France and Dr Burgio provided project management. Dr Goode provided fund procurement. Dr Goode, Dr Weidner, Dr Lukacz, Dr Bradley, Dr Schaffer, and Dr Kenton provided study participants. Dr Burgio, Dr Goode, Dr Lukacz, and Dr Schaffer provided facilities/equipment. Dr Goode, Dr Weidner, Dr Lukacz, Dr Jelovsek, Dr Schaffer, and Dr Kenton provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

Ethics approval was obtained from all of the clinical centers (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Loyola University [Maywood, Illinois], University of Utah, Duke University, University of Iowa, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, University of California, San Diego, University of Texas, Southwestern, Cleveland Clinic) and the Data Coordinating Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

This study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health.

This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT00270998).

References

- 1. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardization Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hay-Smith J, Berghmans B, Burgio K, et al. Adult conservative managment. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, eds. Incontinence. 4th ed Birmingham, United Kingdom: Health Publication Ltd; 2009:1025–1120 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Imamura M, Abrams P, Bain C, et al. Systematic review and economic modelling of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-surgical treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–188, iii–iv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD005654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Wyman J, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:459–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goode PS, Burgio KL, Locher JL, et al. Effect of behavioral training with or without pelvic floor electrical stimulation on stress incontinence in women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fine P, Burgio K, Borello-France D, et al. Teaching and practicing of pelvic floor muscle exercises in primiparous women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:107.e1–e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bø K, Talseth T. Long-term effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise 5 years after cessation of organized training. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bø K, Kvarstein B, Nygaard I. Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic floor muscle exercise adherence after 15 years. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):999–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holley RL, Varner RE, Kerns DJ, Mestecky PJ. Long-term failure of pelvic floor musculature exercises in treatment of genuine stress incontinence. South Med J. 1995;88:547–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Milne JL, Moore KN. Factors impacting self-care for urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs. 2006;26:41–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hay-Smith EJC, Ryan K, Dean S. The silent, private exercise: experiences of pelvic floor muscle training in a sample of women with stress urinary incontinence. Physiotherapy. 2007;93:53–61 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kincade JE, Johnson TM, Ashford-Works C, et al. A pilot study to determine reasons for patient withdrawl from a pelvic muscle rehabilitation program for urinary incontinence. J Appl Gerontol. 1999;18:379–396 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ashworth PD, Hagan MT. Some social consequences of non-compliance with pelvic floor exercises. Physiotherapy. 1993;79:465–471 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alewijnse D, Mesters I, Metsemakers J, et al. Predictors of intention to adhere to physiotherapy among women with urinary incontinence. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen SY, Tzeng YL. Path analysis for adherence to pelvic floor muscle exercise among women with urinary incontinence. J Nurs Res. 2009;17:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bø K, Owe KM, Nystad W. Which women do pelvic floor muscle exercises six months' postpartum? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197;49.e1–e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Goode PS, et al. Adherence to behavioral interventions for urge incontinence when combined with drug therapy: adherence rates, barriers, and predictors. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1493–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgio KL, Whitehead WE, Engel BT. Urinary incontinence in the elderly: bladder –sphincter biofeedback and toileting skills training. Ann Intern Med. 1985;104:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goode PS, Burgio KL, Locher JL, et al. Effect of behavioral training with or without pelvic floor electrical stimulation on stress incontinence in women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. A pelvic muscle precontraction can reduce cough-related urine loss in selected women with mild SUI. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:870–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral versus drug treatment for urge incontinence in older women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1995–2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bhatia NN, Bergman A. Pessary test in women with urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:220–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Komesu YM, Ketai LH, Rogers RG, et al. Restoration of continence by pessaries: magnetic resonance imaging assessment of mechanism of action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:563.e1–e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Goode PS, et al. Non-surgical management of stress urinary incontinence: Ambulatory Treatments for Leakage Associated With Stress (ATLAS) trial. Clin Trials. 2007;4:92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, et al. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:161–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:98–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1388–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burgio KL, Goode PS, Richter HE, et al. Global ratings of patient satisfaction and perceptions of improvement with treatment for urinary incontinence: validation of three global patient ratings. Neurolurol Urodyn. 2006;25:411–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brink CA, Sampselle CM, Wells TJ, et al. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in older women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res. 1989;38:196–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle training is effective in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, but how does it work? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;1334–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1993;73:771–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American College of Sports Medicine American College of Sports Medicine position stand: progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:687–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Graves JE, Pollock ML, Legget SH, et al. Effect of reduced training frequency on muscular strength. Int J Sports Med. 1988;9:316–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:903–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, et al. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med. 2001;33:375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hunskaar S, Vinsnes A. The quality of life in women with urinary incontinence as measured by the sickness impact profile [erratum in: J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:976–977]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:378–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sherburn M, Bird M, Carey M, et al. Incontinence improves in older women after intensive pelvic floor muscle training: an assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hines SH, Seng JS, Messer KL, et al. Adherence to a behavioral program to prevent incontinence. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29:36–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Becker MH. The health belief model and sick behavior. Health Educ Monogr.1974;2:409–419 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JF, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alewijnse D, Mesters I, Metsemakers J, van den Borne B. Predictors of long-term adherence to pelvic floor muscle exercise therapy among women with urinary incontinence. Health Educ Res. 2003;18:511–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Elia G, Bergman A. Pelvic muscle exercises: when do they work? Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:283–286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cammu H, Van Nylen M, Blockeel C, et al. Who will benefit from pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1152–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL, et al. Predictors of outcome in the behavioral treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):940–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hendriks EJ, Kessels AG, de Vet HC, et al. Prognostic indicators of poor short-term outcome of physiotherapy intervention in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Forkan R, Pumper B, Smyth N, et al. Exercise adherence following physical therapy intervention in older adults with impaired balance. Phys Ther. 2006;86:401–410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Williams P, Lord SR. Predictors of adherence to a structured exercise program for older women. Psychol Aging. 1995;10:617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.