Abstract

Objective

The goal of this project was to quantify the prevalence of gaps in cardiology care, identify predictors of gaps, and assess barriers to care among adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) patients.

Background

ACHD patients risk interruptions in care that are associated with undesired outcomes.

Methods

Patients (≥18years) with first presentation to an ACHD clinic completed a survey regarding gaps in, and barriers to, care.

Results

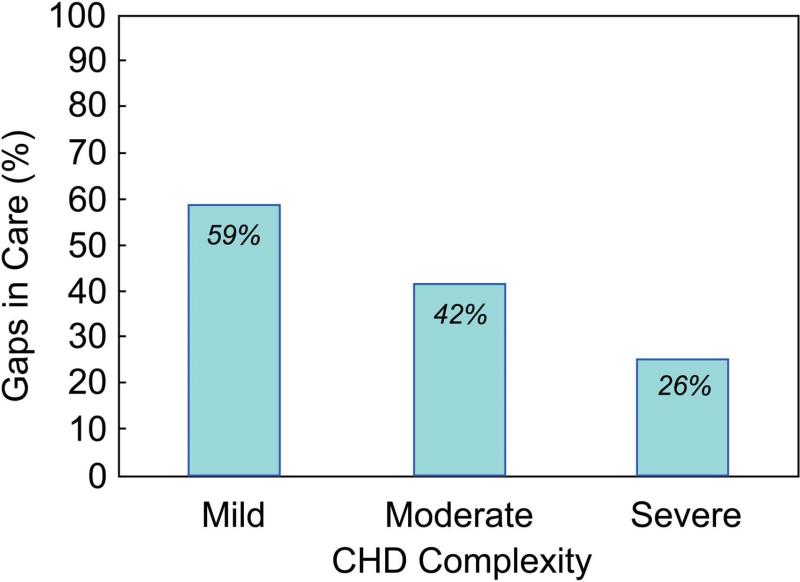

Among 12 ACHD centers, 922 subjects (54% female) were recruited. A >3 year gap in cardiology care was identified in 42%, with 8% having gaps longer than a decade. Mean age at first gap was 19.9 years. The majority of respondents had more than high school education, and knew their heart condition. Most common reasons for gaps included feeling well, unaware follow-up required, and complete absence from medical care. Disease complexity was predictive of gap in care with 59% of mild, 42% of moderate and 26% of severe disease subjects reporting gaps (p<0.0001). Clinic location significantly predicted gaps (p<0.0001) while gender, race, and education level did not. Common reasons for returning to care were new symptoms, referral from provider, and desire to prevent problems.

Conclusions

ACHD patients have gaps in cardiology care; the first lapse commonly occurred around 19 years, a time when transition to adult services is contemplated. Gaps were more common among subjects with mild and moderate diagnoses and at particular locations. These results provide a framework for developing strategies to decrease gaps and address barriers to care in the ACHD population.

Keywords: Congenital, access to care, barriers

Introduction

Advances over the past four decades in diagnosing and treating congenital heart disease (CHD) in children have resulted in over 85% survival into adulthood. The current population of adults in the United States with CHD is estimated at approximately 1 million people (1,2). Most CHD patients require life-long cardiology care and published guidelines recommend care from specialists in adult CHD for approximately half of this population (1,3-5).

Prior studies report that many adult patients are lost to cardiac follow-up, some with gaps in care of 10 years or more (6). In the adult CHD population, a lapse in medical care may result in adverse outcomes. Single center studies have noted that patients with a gap in care are more likely to require urgent cardiac interventions or have under treated cardiac-related medical conditions (6-8). Small cohort studies of patients with congenital heart and other chronic pediatric-onset diseases have likewise suggested that potential barriers to accessing specialized care include deficiency of patient education regarding their condition and the need for regular follow-up, absence of sufficient health insurance, lack of available qualified specialty centers, and negative experiences in adult-oriented care (9-11).

The Alliance for Adult Research in Congenital Cardiology (AARCC), a North American collaboration of adult congenital heart centers dedicated to research (12), and the Adult Congenital Heart Association (ACHA), a national patient advocacy organization, sought to explore the prevalence and duration of gaps in care, and the types of barriers to care experienced by adult CHD patients, as a means to developing future targeted interventions to limit the occurrence and impact of such deficiencies.

Methods

Patient Population

The study population comprised adults (≥18 years of age) with CHD upon their first presentation to one of twelve participating adult CHD care programs based at Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland; University of California Medical Center, Los Angeles; University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle; Children's Hospital Boston, Boston; Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus; University of Colorado Medical Center, Denver; Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; Columbia University Medical Center, New York; Hershey Medical Center, Hershey; Cincinnati Children's Hospital, Cincinnati; Children's National Medical Center, Washington D.C.; and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Patients were required to have a diagnosis of CHD and to be a new patient to the adult CHD clinic between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2010. New patients were defined as those never previously seen in the adult CHD program at that site. Patients were excluded if they did not have congenital heart disease or were unable to complete a survey written at an 8th grade reading level. De-identified data from all centers was sent to the data coordinating center at the Adult Congenital Heart Association.

Study Design

A multicenter prospective cross-sectional study was performed with a questionnaire administered to subjects upon first visit to the adult CHD center. The questionnaire included multiple topics focused on gaps in and barriers to cardiology care. A gap in cardiology care was defined as a more than 3 year interval between any cardiology appointments (internal medicine, pediatric or adult congenital cardiology). Demographic variables collected included sex, race, ethnicity, and education level. Clinical variables included referral source, congenital heart diagnoses (up to 5), and a series of questions regarding the presence and duration of gaps in cardiology care and reasons for leaving and returning to cardiology care. Enrolled subjects were asked to record the number of gaps in cardiology care since age 18 years, the age at which the gaps occurred and the duration of the gaps. For rating barriers to care, we asked subjects what caused them to stop seeing their cardiologist. As it was thought that a decision to leave care might be multifactorial, subjects were asked to rate 19 factors from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. If no choices were appropriate, they were asked to fill in a response, “other”. The “other” responses ranged from “did not think I needed follow up from a cardiologist” to “changed insurance” to “my parents stopped taking me”. The results were evaluated by frequency of response for the group and by categories of complexity of CHD. As the subjects were all new patients to the adult CHD center, they were also asked what prompted return to cardiology care. There were 14 potential options and subjects were asked to respond yes or no to each. The self-reported CHD diagnoses were confirmed by the local research team and each patient was categorized as having anatomically simple, moderate, or complex CHD based on the most complex diagnosis and the categories detailed in the 32nd Bethesda guidelines (2). It was reported to the data coordinating center if the self-reported diagnosis did not match the actual diagnosis. The local research team confirmed additional clinical information by medical record review. The study was approved by each participating site's Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data Analysis

Continuous variables are summarized by mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles), depending on normality of distribution. Categorical variables are represented by frequencies and percentages. The prevalence of gaps in care, underlying reasons, duration, and age of onset were characterized by descriptive statistics. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models assessed demographic and knowledge-based predictors of gaps in care, from which odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived. Two-tailed values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 922 subjects were recruited from the 12 participating adult CHD centers. There was at least one adult CHD center representing each of the 4 main census regions of the United States. The number of subjects per site ranged from 14 to 249 (Table 1). The group was 54% female and 83% white, non-Hispanic. Subject self-reporting suggested that 73% had more than a high school education and 38% completed a bachelor's degree or graduate school. Classification of anatomic complexity of CHD categorized 27% of patients as mild, 51% as moderate and 23% as severe. As a metric of knowledge regarding their own CHD, subjects were asked to name their heart condition and 75% identified such correctly.

Table 1.

Total Participants Per Site and Proportion at Each Site Reporting Gap in Care

| Adult CHD Clinic | City | Total Patients Recruited Total (%) | Reporting Gap (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oregon Health and Sciences University | Portland | 111 (12) | 59 |

| University of California Medical Center | Los Angeles | 24 (2.6) | 22 |

| University of Washington Medical Center | Seattle | 87 (9.4) | 51 |

| Boston Children's Hospital | Boston | 249 (27) | 33 |

| Ohio State University Medical Center | Columbus | 95 (10.3) | 37 |

| University of Colorado Medical Center | Denver | 87 (9.4) | 61 |

| Medical College of Wisconsin | Milwaukee | 63 (6.8) | 42 |

| Columbia University Medical Center | New York | 17 (1.8) | 29 |

| Hershey Medical Center | Hershey | 82 (8.9) | 45 |

| Cincinnati Children's Hospital | Cincinnati | 36 (3.9) | 42 |

| Children's National Medical Center | Washington, D.C. | 52 (6.2) | 36 |

| Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania | Philadelphia | 14 (1.5) | 21 |

Gaps in Care

Forty-two percent of subjects reported a gap in cardiology care. Within this population, 36 % had mild, 50% had moderate, and 14% had severe CHD. Eight percent of patients had at least one gap in care lasting longer than 10 years, and 14% of patients experienced two or more gaps in care. The typical age at first gap in care occurred during the transitional period of young adulthood (mean 19.9±9.1, median 19 years). Complexity of CHD was associated with gaps in care: 59% of mild, 42% of moderate and 26% of severe disease subjects reported care gaps (p<0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gaps in cardiology care by disease complexity.

The percentage of respondents reporting gaps in cardiology care by congenital heart disease diagnosis complexity *Complexity definition per 32nd Bethesda conference guidelines (2)

Clinic location was a significant predictor of having a cardiology care gap (p<.0001). In programs in Colorado, Oregon and Washington State, over 50% of patients reported experiencing a gap in care (Table 1). In contrast, gender, race, education level, and knowledge of disease name were not predictive of gaps. On multivariate analysis, subjects with mild or moderate CHD resulted in a 4.1 or 2.2 fold increased prevalence of cardiology care gaps, respectively, compared to those having severe disease (p<0.0001). Also, coming to care at an adult CHD program in Colorado (p< 0.001), Oregon (p<0.002) and Washington State (p< 0.027) remained strong predictors of having had a gap in cardiology care.

Reasons for Leaving and Returning to Care

Of the 19 factors listed for ratings as potential contributors to gap in cardiology care, the top five responses for the study population had mean Likert scores of 2.4 to 3.3 (Table 2). The highest rated responses varied among subjects with differing CHD complexities. “Changing or losing insurance” and “financial problems” rated highly for the more complex CHD patients. “Lost track of time” and “decreased parental involvement” were rated higher on the list for patients with milder complexity of CHD. (Table 3)

Table 2.

Reported Reasons Why Participants Had a Gap in Cardiology Care

| Reason | Likert mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Felt well | 3.3 ± 1.6 |

| Didn't need follow up | 2.8 ± 1.5 |

| Not receiving medical care | 2.7 ± 1.6 |

| Moved | 2.5 ± 1.7 |

| Changed or lost insurance | 2.4 ± 1.7 |

| Lost track of time | 2.4 ± 1.6 |

| Perceived myself as ‘fixed’ | 2.4 ± 1.5 |

| Was recommended to have care every 3 years | 2.3 ± 1.5 |

| Primary care physician did not recommend | 2.3 ± 1.5 |

| Parents stopped taking me | 2.2 ± 1.5 |

| No Longer Needed follow up | 2.1 ± 1.5 |

| Financial problems | 2.1 ± 1.5 |

| Worried about getting bad news | 1.9 ± 1.3 |

| Primary care physician did cardiac tests | 1.8 ± 1.3 |

| Personal problems | 1.8 ± 1.3 |

| ‘Wanted a break’ from focusing on my heart | 1.7 ± 1.2 |

| Cardiology staff did not understand medical condition | 1.5 ± 1.0 |

| A specific, difficult experience relating to my heart care | 1.4 ± 0.9 |

| Cardiology staff did not understand social/emotional needs | 1.3 ± 0.9 |

Table 3.

Most Common Reasons For Gaps in Cardiology Care by Disease Complexity

| Complexity | Reason | Likert mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | Felt Well | 3.2 ± 1.6 |

| Didn't think needed follow up | 2.8 ± 1.5 | |

| Lost track of time | 2.5 ± 1.6 | |

| Told to follow up every 3 years or more | 2.5 ± 1.6 | |

| Primary did not recommend it | 2.4 ± 1.5 | |

| Not receiving any medical care | 2.4 ± 1.6 | |

| Parents stopped taking me | 2..4 ± 1.6 | |

| Moderate | Felt Well | 3.3 ± 1.5 |

| Didn't think needed follow up | 3 ± 1.4 | |

| Not receiving any medical care | 2.7 ± 1.6 | |

| Changed or lost insurance | 2.5 ± 1.7 | |

| Moved | 2.5 ± 1.6 | |

| Severe | Felt Well | 3.5 ± 1.6 |

| Not receiving any medical care | 3.1 ± 1.7 | |

| Changed or lost insurance | 3.0 ± 1.8 | |

| Moved | 2.8 ± 1.7 | |

| Financial Problems | 2.7 ± 1.6 |

*Mild, Moderate and Severe diagnosis criteria based on 32nd Bethesda Guidelines, 2001

The most common reasons for return to care were a desire to prevent potential problems, a recommendation from another healthcare provider and new symptoms or health problems. (Table 4) Of those subjects referred by a healthcare provider, 31% were referred by an adult cardiologist, 30% by a pediatric cardiologist and 13% by a primary care provider.

Table 4.

Reasons for Returning to Cardiology Care

| Reason for return to care | Yes (%) |

|---|---|

| Desire to prevent potential problems | 70 |

| Recommendation from other health care provider | 65 |

| New symptoms or health problem(s) | 53 |

| Recommendation from family/friends | 47 |

| Desire to learn more about my heart | 46 |

| Concern about potential deterioration | 45 |

| New health insurance | 26 |

| Emergency room visit | 23 |

| Other life changes (ex: marriage, new job) | 23 |

| Better financial situation | 19 |

| Interest in getting pregnant | 14 |

| New adult CHD care services available | 7 |

| Recommendation from ACHA/other health advocacy group | 6 |

| Media story on CHD | 3 |

Discussion

This large cross-sectional study characterizes gaps in cardiology care and barriers to care experienced by adults with CHD and, as such, provides insights into areas to potentially target for intervention. Nearly half of patients experienced more than a 3-year gap at some point in their cardiology care. The presence of gaps in care among this multi-center group of patients resembles the gaps found in smaller single center studies, with first gap in care typically occurring at age 19-20 years. (6,13) This timing reflects a period when patients are more apt to leave a pediatric clinician and enter an internal medicine or adult-oriented healthcare system and is also an age where patients may be relocating or changing insurance providers. The presence and timing of this gap in care is consistent with other literature concerning healthcare transition which similarly demonstrates that patients are often lost to follow up or have an increase in emergency department admissions during young adulthood (9,10,13-17).

The study was conducted at a variety of adult CHD clinics across the US and clinic site was associated with the experience of a gap in care. The reasons for this finding are unclear and it is difficult to draw specific conclusions from our study, as we did not track where respondents had been seen and medically cared for prior to their gaps in care. Some proposed explanations may include the impact of regional geography on ability to travel, demographics of the population in or coming to the city, insurance availability in the state, or even age of the ACHD program. This finding deserves further investigation as it suggests there may be geographic barriers to achieving optimal adult CHD care and outcomes.

CHD complexity was also related to interruptions in care. While a majority of patients with mild heart disease experienced gaps in care, it is possible that some were instructed to return to care at longer intervals than those prescribed to patients with more complex disease. Such possibility of discrepancies in physician-suggested duration between visits may have impacted potential for subsequent care gap (5). Recognizing the increased risk of adverse events and need for more urgent interventions upon return to care after a gap, it is of great concern that the majority of subjects who reported gaps had moderate or severe complexity of CHD anatomic diagnoses.

The stated reasons for gaps in care were informative. ‘Feeling well’ was the primary contributor chosen as reason for a gap in care, regardless of the underlying complexity of the anatomic heart disease. This information highlights that many adults with CHD do not relate symptomatology that would otherwise bring them to medical care; age appropriate reiteration of rationale behind guidelines supporting need for lifelong surveillance and care is recommended for all patients (and parents when appropriate) in pediatric and adult cardiology care settings. Likewise, strategies for protecting access for adults with CHD to sufficient health insurance appear warranted to facilitate maintenance within cardiac care.

Despite our subjects reporting a high level of general education, a large proportion, nonetheless, experienced cardiology care gaps. As we surveyed adults with congenital heart disease sufficiently informed to re-present to cardiology care, we recognize that our findings may significantly underestimate the medical knowledge vacuum that currently exists for the large numbers of adults with congenital heart disease, who are not receiving care via established ACHD centers. We therefore suggest that another potential target for intervention to decrease gaps in cardiac care for adults with CHD is greater engagement and education, coupled with improved awareness of and access to available resources, for referring internists, family practitioners, primary care physicians and both internal medicine and pediatric cardiologists. The advice of a healthcare provider was the second most common reason patients came to adult congenital cardiology care. This strategy is aligned with current American College of Cardiology/Adult Congenital Heart Association national PATCH (Provider Action for Treating Congenital Hearts) programming, currently targeting similar goals for internal medicine and pediatric cardiologists. Taking the potential etiologies for gaps in care and barriers to care into account, the prevalence of gaps in care remains striking and there appear to be accessible targets for action. Continued effort for further detailed analysis of comprehensive existing and novel datasets appears warranted and with potential to impact public health.

Limitations

While this study was large and comprehensive, limitations are recognized. Self-reports of presence and timing of gaps in care were not independently corroborated and are open to potential for confounding by both recall bias as well as patient sense of implications of their responses. The survey was conducted only at established adult CHD centers, and participants were new to the clinics. Patients who were not intellectually capable of completing the questionnaires were excluded from participation. As such, the results may not be representative of adult CHD patient populations outside of the participating specialty centers or with significant developmental delay. Finally, the subjects were asked about a gap in any cardiology care, not specialized adult congenital cardiology care, as the authors were concerned that some subjects may have difficulty differentiating the types of cardiologists or practices and there is no certification for training and competency in adult CHD care at this time. We also cannot account for patients who were never seen and may still be lost to care, therefore not reflected in the study. Thus, the true frequency of gaps in specialized adult congenital cardiology care is likely significantly underestimated.

Conclusion

Adult CHD patients often have interruptions in cardiology care. A first gap in care is most commonly recognized during late teen years, concurrent with the typical time of transition from pediatric to adult oriented medical care. Gaps were more common among those respondents with anatomic diagnoses that were classified to be of moderate and mild complexity, and from respondents receiving care at particular geographic clinic locations. These results provide a foundation for further study and for consideration of public health strategies to decrease barriers to, as well as gaps in, cardiology care for the adult CHD population.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (Grant no: 5 R03 HL096134-02) Disclosures: This project was supported by Award Number R03HL096135 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. No relationships with industry related to this study.

Abbreviations

- CHD

Congenital heart disease

- AARCC

Alliance for adult research in congenital cardiology

- ACHA

Adult Congenital Heart Association

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffman JI, Kaplan S, Liberthson RR. Prevalence of congenital heart disease. Am Heart J. 2004;147:425–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warnes CA, Liberthson R, Danielson GK, et al. Task force 1: the changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;37:1170–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). European Heart Journal. 2010;31:2915–57. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silversides CK, Marelli A, Beauchesne L, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2010;26:143–50. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70352-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52:e1–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung E, Kay J, Roosevelt GE, Brandon M, Yetman AT. Lapse of care as a predictor for morbidity in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:62–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bono J, Freeman LJ. Aortic coarctation repair--lost and found: the role of local long term specialised care. Int J Cardiol. 2005;104:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wacker A, Kaemmerer H, Hollweck R, et al. Outcome of operated and unoperated adults with congenital cardiac disease lost to follow-up for more than five years. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:776–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moons P, De Volder E, Budts W, et al. What do adult patients with congenital heart disease know about their disease, treatment, and prevention of complications? A call for structured patient education. Heart. 2001;86:74–80. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiss JG, Gibson RW, Walker LR. Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives. Pediatrics. 2005;115:112–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verstappen A, Pearson D, Kovacs AH. Adult congenital heart disease: the patient's perspective. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:515–29. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khairy P, Hosn JA, Broberg C, et al. Multicenter research in adult congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moons P, Hilderson D, Van Deyk K. Implementation of transition programs can prevent another lost generation of patients with congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;7:259–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurvitz MZ, Inkelas M, Lee M, Stout K, Escarce J, Chang RK. Changes in hospitalization patterns among patients with congenital heart disease during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49:875–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knauth A, Verstappen A, Reiss J, Webb GD. Transition and transfer from pediatric to adult care of the young adult with complex congenital heart disease. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:619–29. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Therrien J, Pilote L, Abrahamowicz M, Marelli AJ. Children and adults with congenital heart disease lost to follow-up: who and when? Circulation. 2009;120:302–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid GJ, Irvine MJ, McCrindle BW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of successful transfer from pediatric to adult health care among a cohort of young adults with complex congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e197–205. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]