Abstract

Objective

Previous studies have found an association between early age at first sexual intercourse and subsequent psychosocial maladjustment. Using a quasi-experimental approach, we examined the extent to which this observed association may be due to familial confounds not explored in prior research.

Methods

Using a population-based cohort of Swedish adult twins (ages 19–47; N = 12,126), we examined the nature of the association between early sexual intercourse (i.e., first intercourse occurring before age 16) and various outcomes reflecting psychosocial health, including substance use, depression, criminal convictions, and adolescent childbearing. We used two methods—discordant-twin analyses and bivariate twin modeling—to estimate the extent to which genetic and environmental confounds explained observed associations.

Results

Individuals who engaged in early intercourse were at greater risk for most of the adverse psychosocial health outcomes measured in this study. Twin pairs discordant for engaging in early intercourse, however, did not differ significantly in their risk for psychosocial maladjustment. Our results indicated that early age at first sexual intercourse and subsequent psychosocial maladjustment may be associated due to familial factors shared by twins.

Conclusion

Early intercourse may be associated with poor psychosocial health largely due to shared familial influences rather than through a direct causal connection. Effective and efficient interventions, therefore, should address other risk factors common to both early intercourse and poor psychosocial health.

Keywords: adolescence, sexual behavior, sex-education programs, behavior genetics

The formation of sexual identity and healthy relationships are important aspects of adolescent development (Fortenberry, 2003; Halpern, 2010; Tolman & McLelland, 2011), and a majority of individuals report that they have had sexual intercourse by the age of 18 (Danielsson, Rogala, & Sundström, 2001; Eaton et al., 2010; Guttmacher Institute, 2001). However, younger sexually active adolescents are more likely to engage in behaviors that increase their risk of unintended pregnancy and the contraction and spread of STIs (Buston, Williamson, & Hart, 2007; Danielsson et al., 2001; Hollander, 2009; Kaestle, Halpern, Miller, & Ford, 2005; Sandfort, Orr, Hirsch, & Santelli, 2008). The reduction of adolescent sexual risk behaviors— including delaying the onset of sexual activity—could significantly reduce the public-health burden associated with these outcomes (Chesson, Blandford, Gift, Tao, & Irwin, 2004; Hoffman, 2006; Sonfield, Kost, Gold, & Finer, 2011).

Public policy focused on delaying sexual activity has posited that adolescent intercourse may have also negative effects on psychological health (Social Security Act, 1996). Previous research indicates that intercourse in early adolescence (hereafter referred to as “early sex”) tends to co-occur with early-adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substance use (Kotchick, Shaffer, Forehand, & Miller, 2001; Siebenbruner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Egeland, 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2004), depressive symptoms (Lehrer, Shrier, Gortmaker, & Buka, 2006; Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008), and general delinquency (Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008). Early sex is also associated with young–adult delinquency (Armour & Haynie, 2007) and substance use disorders (Cornelius, Clark, Reynolds, Kirisci, & Tarter, 2007; McGue & Iacono, 2005), but has less consistent associations with young-adult depressive symptoms (McGue & Iacono, 2005; Meier, 2007; Rector, Johnson, Noyes, & Martin, 2003; Spriggs & Halpern, 2008).

However, individuals do not engage in early sex or experience adverse psychosocial health outcomes at random. Twin and family studies indicate that familial influences—genetic and/or environmental influences shared by individuals within a family that make siblings or twins similar—contribute to variability in age at first intercourse (Mustanski, Viken, Kaprio, Winter, & Rose, 2007; Rodgers, Rowe, & Buster, 1999), young adult substance use, abuse, and dependence (Kendler et al., 1999; McGue, Pickens, & Svikis, 1992; van den Bree, Johnson, Neale, & Pickens, 1998), lifetime major depression (Kendler, Gatz, Gardner, & Pedersen, 2006), current depressive symptoms in adulthood (Kendler et al., 1994), criminal activity (Frisell, Lichtenstein, & Långström, 2010), and adolescent childbearing (Waldron et al., 2007).

It is possible that familial influences contributing to the likelihood of engaging in early sex overlap with familial influences that increase vulnerability to adverse psychosocial outcomes. These common influences could include genes related to personality traits such as sensation seeking and impulsivity (Verweij, Zietsch, Bailey, & Martin, 2009) or a predisposition for disinhibited behavior (McGue & Iacono, 2005). Environmental factors shared by family members (Dick, Johnson, Viken, & Rose, 2000), such as living in a disadvantaged or unstable household or neighborhood or being raised by parents with low education, poor psychological health, or certain attitudes about engaging in risk-taking behavior, could also contribute to both early sex and psychosocial maladjustment (Kirby, 2003; Roche et al., 2005).

Almost all existing research regarding psychosocial consequences of early sex has compared unrelated individuals to each other (Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008). Such studies are unable to account for between-family differences that could be driving the observed associations (Rutter, 2007; Rutter et al., 2010; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Quasi-experimental methods (Shadish et al., 2002), such as the comparison of twins discordant for risk-factor exposure, can help address the limitations of previous research by controlling for possible familial confounds (Lahey, D’Onofrio, & Waldman, 2009; McGue, Osler, & Christensen, 2010; Rutter, 2007). The discordant-twin analysis provides an estimate of the association between early sex and each outcome that remains after controlling for genetic and environmental confounds.

A more complete understanding of the association between early sex and young-adult adjustment has important implications for public health intervention. If early sex causes adverse psychosocial health outcomes, delaying intercourse onset would reduce the likelihood that these outcomes occur. However, if early sex and adverse psychosocial health outcomes are associated because they are both influenced by a third, unmeasured variable—familial confounds, for example—delaying intercourse onset would not effectively reduce the likelihood of these negative outcomes. Recent studies utilizing the discordant-twin approach have found that early sex is no longer associated with young-adult delinquency (Harden, Mendle, Hill, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2008) or young-adult sexual risk behaviors, including adolescent pregnancy (Huibregtse, Bornovalova, Hicks, McGue, & Iacono, 2011), after controlling for genetic and environmental influences shared by twins. These results suggest that the observed associations are entirely due to familial confounding.

In the current study, we examined the nature of the association between early age at first intercourse and several psychosocial health outcomes in young adulthood, including cigarette use, cannabis use, alcohol abuse/dependence, major depressive episode, current depressive symptoms, criminal conviction, and adolescent childbearing. Using a genetically informative, population-based sample of adult Swedish twins, we tested whether these associations were explained by unmeasured familial confounds. We then used bivariate twin modeling to estimate the degree to which genetic and environmental confounds were responsible for the covariation between early sex and these outcomes.

Methods

Sample

The Study of Twin Adults: Genes and Environment (STAGE) is a registry of adult Swedish twins. The original purpose of STAGE was to assess lifetime history of medical illness, mental disorders, and other health-related behaviors (Lichtenstein et al., 2006). All twin pairs born in Sweden between 1959 and 1985 in which both twins lived past one year of age (N = 42,582) were invited to complete either a Web-based survey or a telephone interview in November 2005 through March 2006. Data collection was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee at the Karolinska Institutet, and participants provided consent while completing the assessment. Participants completing the phone interview were also mailed a separate paper questionnaire assessing potentially sensitive information, including sexual behavior. The total response rate was 59.6%, with 25,381 individuals completing assessments (including 11,235 complete twin pairs plus 2,911 individuals whose cotwin did not participate). The 25,381 STAGE responders did not differ from STAGE nonresponders (n = 17,201) with regard to age, birth weight, or lifetime diagnosis of any neurological condition. Responders were more likely to be female and have Swedish-born parents and less likely to have a history of criminal offending or any psychiatric disorder. Responders were more educated, and responding males had higher intellectual performance scores at the time of conscription (Furberg et al., 2008). We also compared STAGE responders to all individuals born in Sweden between 1959 and 1985 (n = 2,859,123) using data from the Swedish National Crime Register (Fazel & Grann, 2006) and Education Register (Statistics Sweden, 2011). Compared to all individuals born in Sweden between 1959 and 1985, STAGE responders had a comparable mean level of education, prevalence rate of criminal conviction (violent and nonviolent, including driving-related offenses), and parental education and parental criminal history (Donahue, D’Onofrio, Lichtenstein, & Långström, accepted pending minor revisions).

In the current analyses, we examined only monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs and same-sex dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs and only included pairs in which both twins participated in assessments. These inclusion criteria resulted in a subsample of 12,126 individuals from 6,063 twin pairs (3,548 MZ and 2,515 DZ pairs). Of these individuals, 60% were female, and the average age at assessment was 33 years.

Measures

Early sex

Participants were asked whether they had ever engaged in voluntary sexual intercourse, and, if so, at what age they first had intercourse. First intercourse occurring before age 16 was categorized as early sex, in keeping with previous studies of adolescent sexual behavior (Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008). Reported age at first intercourse younger than 10 was coded as missing due to low prevalence rates and concerns about reporting accuracy.

Psychosocial health outcomes

Participants who reported ever smoking and who smoked their first cigarette before age 25 were considered to have engaged in adolescent/young-adult cigarette use. Participants who reported ever using marijuana or hash and who reported such use before age 25 were considered to have engaged in adolescent/young-adult cannabis use.

History of alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, and major depressive episode were measured using a questionnaire based on DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). Because of the low prevalence rates of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, individuals who met diagnostic criteria for either alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence (diagnoses were mutually exclusive) were combined into one group representing individuals who had experienced clinically significant problems with alcohol. In keeping with DSM-IV-TR criteria, the symptoms of alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence had to occur within a 12-month period, and individuals were asked to report their age during the 12-month period in question. Participants meeting criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence by age 25 were considered to have experienced adolescent/young-adult alcohol abuse/dependence.

In keeping with DSM-IV-TR criteria, the symptoms of a major depressive episode had to occur within the same 2-week period, and individuals were asked to report their age the first time they experienced a 2-week period of depressed mood or anhedonia in conjunction with other symptoms. Individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode before the age of 25 were considered to have experienced an adolescent/young-adult major depressive episode.

Participants also responded to 11 items measuring their level of current depressive symptoms, using the abbreviated Iowa form (Carpenter et al., 1998) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977). Participants indicated how often they had experienced any of 11 symptoms in the past week, using a 4-point scale (0 = Never or almost never, 1 = seldom, 2 = often, 3 = always or almost always). Responses across all items were summed, and participants with current symptom levels exceeding eight points (24% of points possible, consistent with percentage thresholds used in the original CES-D scale) were considered to have high current depressive symptoms.

Criminal history was obtained using the Swedish National Crime Register (Fazel & Grann, 2006). The Crime Register is maintained by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention and documents all registered violent, nonviolent, and drug-related convictions in lower courts that occurred in Sweden from 1973–2004, including date of conviction and type of offense, for individuals aged 15 years (i.e., the age of criminal liability in Sweden) and older. Age at first offense was calculated using the participant’s birthdate and earliest date of criminal conviction reported in the Crime Register. Participants convicted of any criminal offense before age 25 were considered to have engaged in adolescent/young-adult criminal offending.

For female participants, childbirth history was obtained using the Swedish Medical Birth Registry. This registry is maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare and includes information on more than 99% of all births occurring in Sweden since 1973, including maternal age at childbirth. Maternal age at first childbirth was calculated, and any participants giving birth prior to age 20 were categorized as having experienced adolescent childbearing.

Participants reporting outcome onset before age 16 were excluded (i.e., deleted listwise) in models for that outcome to ensure that early sex preceded outcome onset. (See Table 1.)

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for a Population-Based Cohort of Adult Swedish Twins

| Measure | M (SD), range | Prevalence | Total n providing data |

% missinga |

n with outcome onset < 16b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Female | -- | 60.4% | 12,126 | 0.0% | -- |

| Age at assessment | 32.6 (7.6), 19–47 | -- | 12,126 | 0.0% | -- |

| Sexual behavior | |||||

| Age at first sexual intercourse | 17.5 (3.1), 10–46 | -- | 8,877 | 26.8% | -- |

| Ever had intercourse | -- | 95.1% | 9,480 | 21.8% | -- |

| First intercourse in early adolescence(<16) | -- | 24.0% | 9,338 | 23.0% | - |

| First intercourse in later adolescence (16-19) | -- | 53.4% | 9,338 | 23.0% | -- |

| Outcomes | |||||

| Cigarette use by age 25 | -- | 54.8% | 8,549 | 29.5% | 2,975 |

| Cannabis use by age 25 | -- | 14.0% | 11,654 | 3.9% | 243 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence by age 25 | -- | 3.9% | 11,263 | 7.1% | 26 |

| Major depressive episode by age 25 | -- | 9.0% | 10,584 | 12.7% | 303 |

| High current depressive symptoms | -- | 32.3% | 11,135 | 8.2% | 314 |

| Criminal offending by age 25 | -- | 9.9% | 12,102 | 0.2% | 158 |

| Childbearing by age 20 (females only) | -- | 2.7% | 7,322 | 0.0% | 4 |

Note: M, mean; SD, standard deviation; n, number of individuals.

Missing data did not systematically vary by age or gender.

Number of individuals with data available for each outcome but with a reported age of onset younger than 16 years. These individuals were excluded from further analyses for that outcome.

Statistical Analyses

First, a series of logistic regression models was run for each outcome using Mplus version 6.1 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). We began by estimating the magnitude of the association between early sex and the outcome across the overall sample while controlling for gender and age (but without considering the cotwin’s status). This initial model accounted for the clustered nature of the data using robust standard errors.

Discordant-twin analyses

Next, we compared twins discordant for early sex. We first ran models including all twin pairs, ignoring zygosity, and then separately by zygosity. We used a two-level logistic regression model comprised of a within-pair effect and a between-pair effect to account for the clustered nature of the data (i.e., individuals nested within twin pairs) (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). We calculated a mean early-sex score for each twin pair (0.0 = concordant for no early sex, 0.5 = discordant, 1.0 = concordant for early sex) and calculated a deviation score for each individual twin from their pair-mean score. A deviation score greater than 0 indicated a twin who engaged in early sex whose cotwin did not. The within-pair effect corresponded to the regression of the outcome on the participant’s deviation score, with the intercept treated as a random effect varying across twin pairs (i.e., individuals were nested within twin pairs with varying levels of mean early-sex exposure). The slope was treated as a fixed effect because twin pairs do not have enough cluster members to allow the slopes to vary across clusters (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Fitting the within-pair parameter is equivalent to fitting econometric fixed-effects models (Neuhaus & McCulloch, 2006), and the estimate for the within-pair parameter corresponds to the change in outcome risk predicted by early sex relative to no early sex, controlling for familial characteristics shared within a twin pair (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). For this reason, the within-pair effect is the parameter of interest in these models (Begg & Parides, 2003). Gender and age were also included as covariates in these models.

We also calculated a zygosity × deviation-score interaction term to test whether the within-twin effect of early sex differed between discordant DZ and MZ pairs (coded as DZ = 1 and MZ = 0). The interaction term was added as a within-pair parameter with all twins included in this model. A nonsignificant interaction term would indicate no difference in outcome risk in DZ vs. MZ pairs. Discordant DZ and MZ twins at equivalent risk would suggest confounding due to shared environmental influences because both twins in discordant DZ and MZ pairs were exposed to these shared environmental factors. A significant interaction parameter would indicate a significant difference in the within-pair estimates for MZ vs. DZ twins. A significantly smaller effect in MZ twins than in DZ twins would indicate genetic confounding of the association between early sex and the outcome, because MZ pairs share a greater amount of additive genetic influences (100% vs. an average of 50% for DZ pairs).

To be included in the models described above comparing unrelated individuals and discordant twins, a participant had to have provided data on the outcome in question and also belong to a twin pair in which both twins reported on early sex. (For ns, see Table 2 footnote.)

Table 2.

Estimated Effects of Early Sexual Intercourse on Adverse Psychosocial Health Outcomes from Analyses of Unrelated Individuals and Discordant Twin Pairs

| Effect of Early Intercoursea |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrelated individuals |

All discordant twins | Discordant DZ twins |

Discordant MZ twins |

Zygosity × exposure |

|||||

| Outcome | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | B(SE) |

| Cigarette use (rMZ = .63, rDZ = .28) |

1.00 | [0.78, 1.29] | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Cannabis use (rMZ = .69, rDZ = .41) |

1.76* | [1.49, 2.09] | 1.41 | [0.96, 2.09] | 1.39 | [0.83, 2.33] | 1.41 | [0.80, 2.49] | 0.07 (0.40) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence (rMZ = .57, rDZ = .22) |

1.78* | [1.33, 2.38] | 1.23 | [0.65, 2.31] | 1.34 | [0.54, 3.32] | 1.14 | [0.48, 2.67] | 0.17 (0.65) |

| Major depressive episode (rMZ = .44, rDZ = .36) |

1.04 | [0.83, 1.31] | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| High current depressive symptoms (rMZ = .40, rDZ = .16) |

1.22* | [1.07, 1.39] | 0.99 | [0.76, 1.29] | 1.25 | [0.87, 1.78] | 0.76 | [0.52, 1.10] | 0.51 (0.26)* |

| Criminal offending (rMZ = .61, rDZ = .44) |

2.04* | [1.67, 2.48] | 1.49 | [0.97, 2.31] | 1.65 | [0.83, 2.33] | 1.32 | [0.69, 2.53] | 0.27 (0.44) |

| Adolescent childbearing (rMZ = .58, rDZ = .48) |

4.11* | [2.67, 6.36] | 2.27* | [1.06, 4.87] | 2.86 | [0.88, 9.26] | 1.78 | [0.67, 4.71] | 0.50 (0.77) |

Note:OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; B, unstandardized logit coefficient; SE, standard error. Gender and age are included as covariates in all models (effects not shown). To be included in models for each outcome, participants had to provide data on outcome exposure and also have an early sex pair-mean score available. (Cigarette use: available n = 2,092; cannabis use: n = 7,215; alcohol abuse/dependence: n = 7,176; major depressive episode: n = 6,574; high current depressive symptoms: n = 6,903; criminal offending: n = 7,490; adolescent childbearing: n = 3,654).

Early intercourse (< age 16) vs. reference category of later intercourse onset (age 16+) used in analyses for all outcome variables except for adolescent childbearing. For models predicting adolescent childbearing (by age 20), the reference category was restricted to intercourse onset at ages 16–19.

p < .05

Bivariate twin model

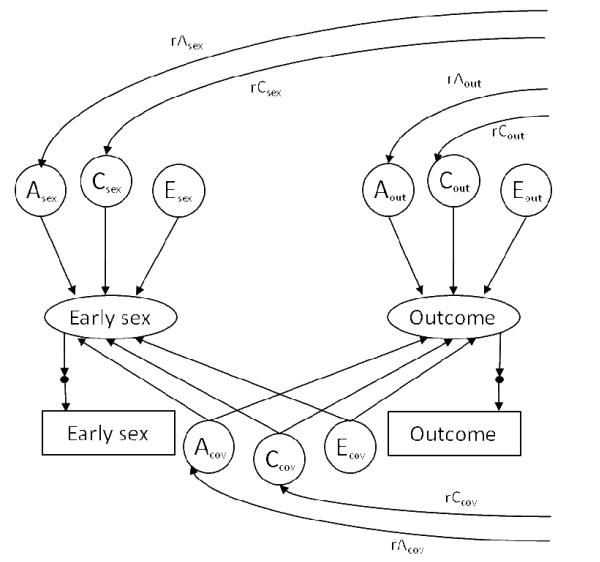

For those outcomes in which there was (1) a significant unadjusted association between early sex and the outcome and (2) for which discordant-twin analyses suggested familial confounding of that association, bivariate twin modeling was used to obtained more precise estimates of the degree to which these confounds were genetic vs. environmental in nature. These structural twin models provided estimates of variance due to additive genetic influences (A), common environmental influences shared by twins (C), or nonshared environmental influences unique to each participant (E). We used a “common-and-specific–factors” model (Figure 1; Loehlin, 1996; Young-Wolff, Kendler, Ericson, & Prescott, 2011), allowing us to estimate A, C, and E contributing (1) specifically to early sex (latent factors Asex, Csex, and Esex); (2) specifically to the outcome (Aout, Cout, and Eout), and (3) to the covariance between early sex and the outcome (Acov, Ccov, and Ecov). Structural equation modeling was completed in Mplus version 6.1 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) using methods recommended by Prescott (2004) for bivariate twin modeling with categorical variables. For each outcome, a twin pair had to have at least one available data point (i.e., information on early sex for either twin or outcome for either twin) in order to be included in the bivariate models for that outcome. As many as 6,063 twin pairs (the full sample) could be included in each bivariate model. Those missing data on all variables were excluded from models for that outcome (cannabis, excluded n = 17; alcohol abuse/dependence, 13; high current depressive symptoms, 30; criminal offending, 6; adolescent childbearing, 299).

Figure 1.

Path diagram for a standardized common-and-specific–factors twin model (shown for one twin in a pair) representing the covariation between early intercourse and the outcome: additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C), and nonshared environmental influences (E). Values for rAsex, rAout, and rAcov were fixed at 1.0 in MZ pairs and 0.5 in DZ pairs, and values for rCsex,rCout, and rCcov were fixed at 1.0 in both MZ pairs and DZ pairs. Thresholds for the binary early intercourse and outcome variables were estimated but not shown, with residual variance for early intercourse and outcome variables fixed at zero. Path estimates from Acov, Ccov,

Results

Descriptive statistics for all measured variables are shown in Table 1. Early sex was reported by 24% of individuals, consistent with data from other Swedish samples (Danielsson et al., 2001). Seven hundred eighty MZ pairs (17%) and 746 DZ pairs (25%) were discordant for early sex. The within-pair tetrachoric correlation for early sex was higher in MZ pairs (r = .78) than in DZ pairs (r = .53).Within-pair correlations for each measured outcome are included in Table 2 and indicate significant within-pair similarity for each outcome. MZ correlations were stronger than DZ correlations for all outcomes, suggesting that genetic factors may influence variability in these behaviors.

In Table 2, the column labeled “Unrelated Individuals” shows the estimated effects of early sex on each outcome among all individuals in the sample. As described previously, these effects are comparable to effects estimated in traditional studies comparing unrelated individuals to one another. Early sex was associated with significantly higher risk of all outcomes, except for cigarette smoking and major depressive episode.

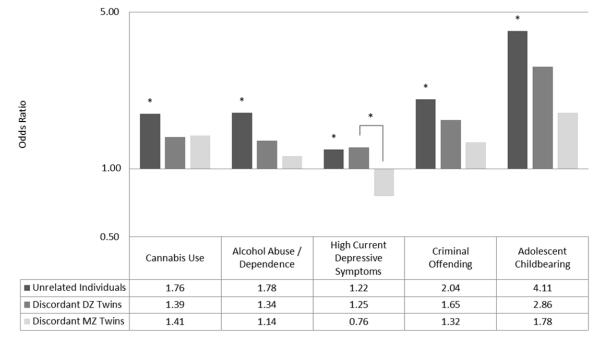

Discordant-Twin Analyses

For each outcome significantly associated with early sex, we then conducted discordant-twin analyses to estimate the effects of early sex on that outcome after controlling for potential familial confounds. (Discordant twin analyses were not conducted for cigarette use or major depressive episode, due to a lack of association in the initial model.) The remaining columns of Table 2 show the estimated within-pair effects of early sex among discordant twin pairs, within-pair effects separated by zygosity, and estimates of the zygosity × deviation score interaction. The odds ratios corresponding to the association of early sex with each outcome from comparisons of unrelated individuals and the within-twin effect of early sex on each outcome among discordant DZ and MZ twin pairs are also displayed graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Odds ratios for experiencing outcome based on differential engagement in early intercourse, by degree of relatedness. A logarithmic scale was used on the y-axis to illustrate the relative magnitude of effect of odd ratios less/greater than 1.0. Significant effects (p < .05) are denoted by *.

For almost every measured outcome, the within-twin effect of early sex was attenuated, relative to the effect found among unrelated individuals, and was no longer significant. This was true when examining all discordant twins and when examining each zygosity type separately. These results suggest that a twin who engaged in early sex and their cotwin who did not engage in early sex did not differ significantly with regard to subsequent cannabis use, alcohol abuse/dependence, high current depressive symptoms, or criminal offending.

The one exception was that females who engaged in early sex were more than four times as likely to report giving birth by the age of 20 when compared to females who first had sex later in adolescence. When examining all discordant twins, affected twins were significantly more likely to report adolescent childbearing than their unaffected cotwins, OR = 2.27, 95% CI [1.06, 4.87]. As the effect was significant when comparing all discordant twins (n= 3,654) but not when comparing twins separately by zygosity (nDZ = 1,418; nMZ = 2,236), we may lack power to detect significant effects, given the low base rate of adolescent childbearing (2.7%) plus the low prevalence of female twins discordant for adolescent childbearing (n = 166, or 4.5%).

For nearly all measured outcomes, there was not a significant interaction of zygosity × exposure (see Table 2, far-right column), suggesting that shared environmental influences explain part of the association between early sex and each of these outcomes. The one exception was for high current depressive symptoms—the within-twin effect of early sex on high current symptoms was significantly higher among DZ pairs than among MZ pairs (B = 0.51, SE = 0.26), suggesting that genetic influences may explain the association between early sex and current depressive symptoms.

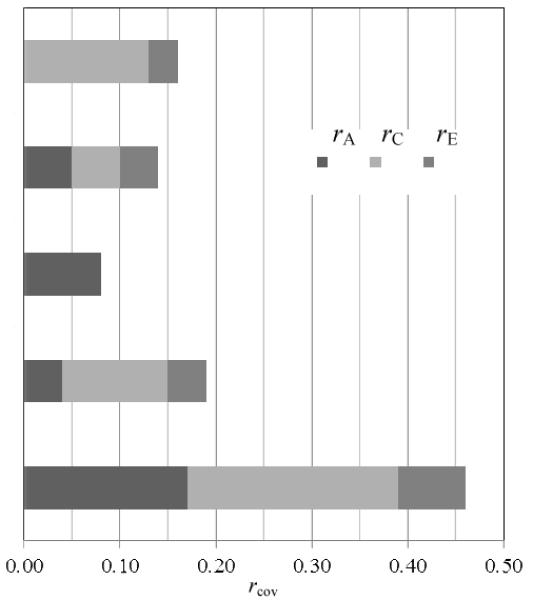

Bivariate Twin Models

Because the results from the discordant-twin analyses suggested that familial confounding may contribute to the association between early sex and cannabis use, alcohol abuse/dependence, high current depressive symptoms, criminal offending, and adolescent childbearing, we used a common-and-specific–factors twin model to estimate the degree to which the overlap between early sex and each of these outcomes was due to A, C, and E. Table 3 presents the standardized path estimates for A, C, and E, representing influences on the covariation between early sex and the outcome as well as influences specific to early sex and to the outcome. The relative contribution of A (rA), C (rC), and E(rE) to the total correlation (rcov) between early sex and each outcome are also shown in Table 3. Because there was no association between early sex and subsequent cigarette use or major depressive episode in the initial models and these outcomes were not included in the discordant twin analyses, bivariate twin models were not conducted for either of these outcomes.

Table 3.

Standardized Path Estimates from Bivariate Twin Models Estimating the Covariation Between Early Intercourse and Each Outcome

| Path estimate (β) |

Covariation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Early sex (specific) |

Outcome (specific) |

Early sex and outcome (common) |

r cov |

rA, rC, or rE |

Proportion of rcov due to of rA, rC, or rE |

|

| Cannabis use | A | 0.70* | 0.74* | 0.06 | 0.16* | 0.00 |

|

| C | 0.39* | 0.17 | 0.36* | 0.13 | |||

| E | 0.45* | 0.52* | 0.16 | 0.03 | |||

| Alcohol abuse & dependence |

A | 0.67* | 0.69* | 0.22 | 0.14* | 0.05 | |

| C | 0.48* | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.05 | |||

| E | 0.44* | 0.60* | 0.19 | 0.04 | |||

| High current depressive symptoms |

A | 0.64* | 0.50* | 0.29* | 0.08* | 0.08 | |

| C | 0.53* | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| E | 0.47* | 0.79* | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Criminal offending |

A | 0.68* | 0.48* | 0.21 | 0.19* | 0.04 | |

| C | 0.41* | 0.50* | 0.33* | 0.11 | |||

| E | 0.43* | 0.58* | 0.20* | 0.04 | |||

| Adolescent childbearing |

A | 0.58* | 0.26 | 0.41* | 0.45* | 0.17 | |

| C | 0.24 | 0.45* | 0.47* | 0.22 | |||

| E | 0.40* | 0.53* | 0.26* | 0.07 | |||

Note: β, standardized path estimate; A, additive genetic influence; C, shared environmental influence; E, nonshared environmental influence. Relative contributions of A, C, and E to overlap (rcov) between early sex and outcome represented by rA, rC, and rE.

p < .05.

There was significant albeit small to moderate covariation between early sex and each outcome. (See column corresponding to rcov in Table 3.) The highest covariation was found between early sex and adolescent childbearing (rcov = 0.45).

Shared environmental influences significantly contributed to the covariation between early sex and cannabis use, accounting for 0.13 (81%) of the total correlation between early sex and cannabis use (rcov = 0.16) and suggesting that environmental influences shared within families primarily explain the observed association between engaging in early sex and subsequent cannabis use by young adulthood.

Although there was significant covariation (rcov = 0.14) between early sex and alcohol abuse/dependence, path estimates for genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental covariance were all nonsignificant, suggesting that familial confounding may contribute to the association between early sex and subsequent alcohol abuse/dependence, but we may have lacked the power to partition the source of confounding into specific sources.

Genetic influences significantly contributed to the covariation between early sex and high current depressive symptoms, accounting for 100% of the total covariation between early sex and high current symptoms (rcov = 0.08) and suggesting that common genetic influences account for the observed association between engaging in early sex and endorsing a high number of depressive symptoms in adulthood.

Environmental influences, both shared and nonshared, significantly contributed to the covariation between early sex and criminal offending, accounting for 57% and 21%, respectively, of the total covariation between early sex and criminal offending (rcov = 0.19). These results suggest that environmental influences shared within families account for a majority of the observed association between early sex and subsequent criminal offending. However, nonshared environmental factors, or environmental influences not shared by both twins, contributed to both early sex and criminal offending also play a role in this observed association.

Familial influences, both genetic and environmental, as well as nonshared environmental influences, significantly contributed to the covariation between early sex and adolescent childbearing. Genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental influences accounted for 37%, 49%, and 14% of the total covariation between early sex and adolescent childbearing (rcov = 0.45), suggesting that influences shared within a family account for a large portion (86%) of the observed association between early sex and childbearing in adolescence. However, nonshared environmental factors that contribute to both early sex and adolescent childbearing may also play a role.

Sensitivity analyses

In the presented analyses, participants who reported having experienced an outcome by the age of 25 were considered to have experienced that outcome by young adulthood. However, a minority of participants (19.5%) had not reached age 25 by the time of assessment but were included in the presented analyses. These participants had not lived through the entire risk period for experiencing an outcome, but it is possible that they could still experience the outcome after the time of assessment but before reaching age 25. To address the possibility that including these individuals could bias results, discordant-twin analyses and bivariate twin models for each outcome were run excluding all individuals who had not yet reached the age of 25. Similar results were found for all outcomes (results not shown).

The presented discordant-twin analyses, with the exception of adolescent childbearing, compared individuals reporting first intercourse in early adolescence (before age 16) to individuals delaying intercourse onset until age 16 or later. Analyses comparing individuals reporting early sex to individuals reporting intercourse onset restricted to later in adolescence (ages 16–19) resulted in a similar pattern of results for all outcomes (not shown).

Given the retrospective nature of the measured outcome data and the potential for recall bias or inaccurate reporting of age at onset for psychiatric disorders (Simon & Von Korff, 1995), we also ran additional analyses to explore whether potential recall bias or onset inaccuracies could affect our reported results. We first ran discordant-twin analyses for each of the psychiatric outcomes (i.e., a major depressive episode and each substance-related outcome) without restricting outcome exposure to before the age of 25. In other words, any individual in the sample reporting that they experienced the outcome at any point in their lifetime prior to assessment was included, regardless of reported age at onset, in order to reduce potential bias introduced by constructing the outcome measure using a potentially inaccurate reported age of onset. Again, similar results were found for all outcomes (not shown). Additionally, we tested whether the age of the participant at assessment (in effect, the amount of time elapsed since early sex or the outcome occurred) affected the association between early sex and the outcome by adding an interaction term (early sex × age) to models estimating the association between early sex and outcome among unrelated individuals. This interaction term was nonsignificant in models for every outcome (results not shown).

Discussion

Using a population-based registry of 20–47-year-old Swedish twins, we explored whether familial confounding accounted for the associations between early sex and several measures of psychosocial health, including substance use, depression, criminal activity, and adolescent childbearing. This approach has rarely been applied in studies examining consequences of early sex, despite numerous calls for studies testing alternative explanations (Harden et al., 2008; Huibregtse et al., 2011; Sandfort et al., 2008; Udell, Sandfort, Reitz, Bos, & Dekovic, 2010).

Compared to unrelated individuals with later intercourse onset, STAGE respondents who reported voluntary sexual intercourse before age 16 were more likely to use cannabis, experience alcohol abuse or dependence, and be convicted of a criminal offense by the age of 25. They were also more likely to endorse high levels of depressive symptoms as adults and, among females, to have children as adolescents. Twins discordant for early sex, however, did not differ significantly in their risk of experiencing any of these outcomes (with the exception of adolescent childbearing). Bivariate twin models also suggested that familial confounds contribute to the covariation between early sex and these outcomes.

This study adds to an emerging line of research investigating the contribution of genetic and environmental confounds to consequences attributed to adolescent sexual behavior by using a powerful quasi-experimental approach (Lahey et al., 2009; McGue et al., 2010). In combination with previous studies using different samples and varying measures of psychosocial health (Harden et al., 2008; Huibregtse et al., 2011), our results provide converging evidence that familial background factors play an important role in the association between early sex and psychosocial health outcomes. Sexual education programs aimed solely at delaying intercourse onset may be unlikely to greatly reduce an individuals’ risk of “psychological harm” (Social Security Act, 1996) as measured in the current study. Instead, the associations between early sex and adverse psychosocial health outcomes may be the result of other risk factors common to both variables. These risk factors may include environmental influences such as general adversity faced by the adolescent’s family (Kirby, 2003; Roche et al., 2005), including neighborhood safety or disadvantage, parenting style, and parents’ own psychological health and emotional stability (Brook, Brook, Rubenstone, Zhang, & Finch, 2010).

While the associations of early sex with adolescent childbearing and criminal offending were predominantly explained by familial factors, the bivariate twin models also pointed toward the importance of nonshared environmental influences. Twins who engage in early sex could be at increased risk for adolescent childbearing due to environmental influences not shared with their twin; a twin who engages in early sex may also use contraceptives less effectively, have more sexual partners, or simply have increased opportunity for unintended pregnancy due to a greater number of years spent sexually active. A twin who engages in early sex may also spend more time with deviant peers, which could contribute to the association between early sex and later criminal behavior. However, variables such as contraceptive use, number of partners during adolescence, and peer deviance were not measured in STAGE. Future research should explore these variables as possible mediators of the association between early sex and adverse outcomes.

While the association between early sex and outcome risk was reduced in the compariso of discordant twins relative to the comparison of unrelated individuals, the odds ratios for several outcomes (e.g., cannabis use, alcohol abuse/dependence, and criminal offending) were not trivial, although they were nonsignificant. Because models comparing unrelated individuals and discordant twins for an outcome were run using the same sample of individuals, this should not be due to a reduction in power related to diminished sample size. Instead, this may be due to somewhat low prevalence rates for the outcome and a decreased ability to estimate outcome risk precisely when comparing discordant twins. In combination with results from the bivariate twin model, however, these results do suggest that there is significant familial confounding of the association between early sex and these outcomes.

Several other limitations of the study should also be considered. The STAGE survey relied upon retrospective reports of lifetime behaviors assessed during adulthood, and recall bias may have contributed to measurement error in reported age at initiation. However, the prevalence of early sexual activity reported retrospectively in this sample is similar to rates of early sex reported prospectively in adolescent samples, suggesting minimal recall bias. The prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders occurring by age 25, based on retrospective reports regarding onset, were also similar to rates reported in prospective samples of young adults (Kessler et al., 2005). Sensitivity analyses exploring the potential effects of recall error also resulted in findings similar to those in the original analyses. In future research, prospective reporting of mood, substance use, and sexual behavior would provide a more precise assessment of the link between these risk factors and sexual risk behavior. However, few population-based datasets meet these criteria and also allow for the use of quasi-experimental designs.

The discordant-twin analyses could be completed only when both twins provided information for all relevant variables. Despite an overall response of roughly 60% among eligible participants, the basic demographic characteristics of STAGE participants were comparable to those of all individuals belonging to the same birth cohort in Sweden. This suggests that missing data in STAGE are likely missing at random and results may be generalizable to the broader Swedish population. Our results may not be readily generalizable to American adolescents, however, due to national differences in attitudes toward adolescent sexuality (Guttmacher Institute, 2001). Relative to adolescents in the United States, Swedish adolescents have easier access to contraceptives and other reproductive health services and have higher rates of contraceptive use (Guttmacher Institute, 2001; Santelli, Sandfort, & Orr, 2009). Swedish adolescents are also provided with more comprehensive sexual education in combination with greater societal acceptance of adolescent sexuality. It is possible that early sex may be more strongly associated with adverse psychosocial health outcomes for American adolescents, given the less supportive climate surrounding adolescent sexuality in the United States. It is worth noting, however, that previous studies finding support for familial confounding have been conducted using data from U.S. samples (Harden et al., 2008; Huibregtse et al., 2011).

Low base rates of some outcomes included in the current study—particularly alcohol abuse/dependence and adolescent childbearing—may have limited our power to detect significant effects. In this case, the results of discordant-twin analyses would overstate the importance of familial confounds in the association between early sex and each outcome at the expense of possible causal influences. It is again noted, however, that analyses comparing affected and unaffected individuals (treating all twins as individuals) and analyses comparing discordant twins (not accounting for zygosity) were conducted using data from the same number of individuals. Nevertheless, given this limitation, the results of our analyses should be interpreted cautiously, and a causal role of early sex on these measures of psychosocial adjustment cannot be definitively ruled out. The bivariate twin models, on the other hand, do not rely solely on the analysis of discordant twin pairs and did indicate that familial influences contributed substantially to the covariation between early sex and each outcome. Our results suggest that previous research not accounting for these unmeasured familial confounds may have overstated the relationship between early sex and subsequent health outcomes, and future research should consider such confounding factors.

Conclusion

The current study represents an underutilized but powerful approach to investigating the relationship between early sex and subsequent psychosocial health. Our results suggest that familial confounds may play an important role in increasing the likelihood of undesirable outcomes among individuals who are also at greater risk for engaging in sex during early adolescence. This means that preventive interventions designed to reduce these negative psychosocial health outcomes should not solely target delaying age at first intercourse if they hope to reduce the prevalence of these adverse outcomes. Future research incorporating genetically informative designs is needed to provide additional insight into the mechanisms connecting sexual and mental health, particularly among adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by award numbers F31 DA 029376-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and T32 HD 007475 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 2011 Behavior Genetics Association annual meeting in Newport, RI.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) 4th Edition American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Armour S, Haynie DL. Adolescent sexual debut and later delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Begg MD, Parides MK. Separation of individual-level and cluster-level covariate effects in regression analysis of correlated data. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:2591–2602. doi: 10.1002/sim.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Finch SJ. A longitudinal study of sexual risk behavior among the adolescent children of HIV-positive and HIV-negative drug-abusing fathers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buston K, Williamson L, Hart G. Young women under 16 years with experience of sexual intercourse: Who becomes pregnant? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2007;61(3):221–225. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Wilson J, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Sachs B, Cunningham L. Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1998;19:481–494. doi: 10.1080/016128498248917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson H, Blandford J, Gift T, Tao G, Irwin K. The estimated direct medical cost of sexually transmitted diseases among American youth, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:11–19. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.11.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Clark DB, Reynolds M, Kirisci L, Tarter R. Early age of first sexual intercourse and affiliation with deviant peers predict development of SUD: A prospective longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):850–854. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson M, Rogala C, Sundström K. Teenage sexual and reproductive behavior in developed countries: Country report for Sweden. Guttmacher Institute; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DD, Johnson JK, Viken RJ, Rose RJ. Testing between-family associations in within-family comparisons. Psychological Science. 2000;11:409–413. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue KL, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Långström N. Risk factors for early intercourse: Testing putative causal associations in the Study of Twin Adults: Genes and Environment (STAGE) Archives of Sexual Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9947-1. accepted pending minor revisions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Grann M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1397–1403. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD. Adolescent sex and the rhetoric of risk. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing Adolescent Risk: Toward an Integrated Approach. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. pp. 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Långström N. Violent crime runs in families: A total population study of 12.5 million individuals. Psychological Medicine. 2010;41:97–105. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL, Thornton L, Bulik CM, Lerman C, Sullivan PF. The STAGE cohort: A prospective study of tobacco use among Swedish twins. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1727–1735. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute . Executive summary: Can more progress be made? Teenage sexual and reproductive behavior in developed countries. The Alan Guttmacher Institute; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT. Reframing research on adolescent sexuality: Healthy sexual development as part of the life course. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42:6–7. doi: 10.1363/4200610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Mendle J, Hill JE, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Rethinking timing of first sex and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(4):373–385. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman S. By the numbers: The public costs of teen childbearing. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; Washington, D.C.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander D. In the period before age 21, women, but not men, may have elevated STD risks. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2009;41(2):129–130. [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse BM, Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, McGue M, Iacono W. Testing the role adolescent sexual initation in later-life sexual risk behavior: A longitudinal twin design. Psychological Science. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0956797611410982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, Ford CA. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161(8):774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:109–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Sullivan PF, Corey LA, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:299–308. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Walters EE, Truett KR, Heath AC, Neale MC, Martin NG, Eaves LJ. Sources of individual differences in depressive symptoms: Analysis of two samples of twins and their families. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1605–1614. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Risk and protective factors affecting teen pregnancy and the effectiveness of programs designed to address them. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand R, Miller KS. Adolescent sexual risk behavior: a multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:493–519. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, D’Onofrio BM, Waldman ID. Using epidemiologic methods to test hypotheses regarding causal influences on child and adolescent mental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(1-2):53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school bstudents. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Sullivan PF, Cnattingius S, Gatz M, Johansson S, Carlström E, Pedersen NL. The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millenium: An update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9(6):875–882. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. The Cholesky approach: A cautionary note. Behavior Genetics. 1996;26(1):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG. The association of early adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1118–1119. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Osler M, Christensen K. Causal inference and observational research: The utility of twins. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:546–556. doi: 10.1177/1745691610383511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Pickens RW, Svikis DS. Sex and age affects on the inheritance of alcohol problems: A twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:3–17. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier AM. Adolescent first sex and subsequent mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112(6):1811–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Viken RJ, Kaprio J, Winter T, Rose RJ. Sexual behavior in young adulthood: A population-based twin study. Health Psychology. 2007;26(5):610–617. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. 6th ed Author; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus JM, McCulloch CE. Separating between- and within-cluster covariate effects by using conditional and partitioning methods. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 2006;68:859–872. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA. Using the Mplus computer program to estimate models for continuous and categorical data from twins. Behavior Genetics. 2004;34:17–40. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000009474.97649.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rector RE, Johnson KA, Noyes LR, Martin S. The harmful effects of early sexual activity and multiple sexual partners among women: A book of charts. The Heritage Foundation; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, Mekos D, Alexander CS, Astone NM, Bandeen-Roche K, Ensminger ME. Parenting influences on early sex initiation among adolescents: How neighborhood matters. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26(1):32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JL, Rowe DC, Buster M. Nature, nurture and first sexual intercourse in the USA: Fitting behavioral genetic models to NLSY kinship data. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1999;31:29–41. doi: 10.1017/s0021932099000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Proceeding from observed correlation to causal inference: The use of natural experiments. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:377–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Belsky J, Brown G, Dunn J, D’Onofrio BM, Eekelaar J, Witherspoon S. Social science and family policies. British Academy Policy Centre; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TGM, Orr M, Hirsch JS, Santelli J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: Results from a national U.S. study. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:155–161. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J, Sandfort TG, Orr M. U.S./European differences in condom use (To the editor) Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:306. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Siebenbruner J, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Egeland B. Sexual partners and contraceptive use: A 16-year prospective study predicting abstinence and risk behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(1):179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M. Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: Implications for epidemiological research. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1995;17:221–227. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage Publishers; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Act 42 U.S.C. Title 5, § 510 (b2E) Separate Program for Abstinence Education. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Sonfield A, Kost K, Gold RB, Finer LB. The public costs of births resulting from unintended pregnancies: National- and state-level estimates. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43:94–102. doi: 10.1363/4309411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs AL, Halpern CT. Sexual debut timing and depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(9):1085–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9303-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden Educational attainment of the population. 2011 from http://www.scb.se/Pages/Product____9577.aspx.

- Tolman DL, McLelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000-2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Udell W, Sandfort T, Reitz E, Bos H, Dekovic M. The relationship between early sexual debut and psychosocial outcomes: A longitudinal study of Dutch adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:1133–1145. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9590-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bree MBM, Johnson EO, Neale MC, Pickens RW. Genetic and environmental influences on drug use and abuse/dependence in male and female twins. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;52:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij KJH, Zietsch BP, Bailey JM, Martin NG. Shared aetiology of risky sexual behaviour and adolescent misconduct: Genetic and environmental influences. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2009;8:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M, Heath AC, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Martin NG. Age at first sexual intercourse and teenage pregnancy in Australian female twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10(3):440–449. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Kendler KS, Ericson ML, Prescott CA. Accounting for the association between childhood maltreatment and alcohol-use disorders in males: A twin study. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:59–70. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: Developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender, and ethnic background. Developmental Review. 2008;28:153–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, Collins WA. A prospective study of intraindividual and peer influences on adolescents’ heterosexual romantic and sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33:381–394. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028891.16654.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]