Abstract

Background

Response to alcohol is a widely studied risk factor and potential endophenotype for alcohol use disorders. Research on African American response to alcohol has been limited despite large differences in alcohol use between African Americans and European Americans. Extending our previous work on the African American portion of this sample, the current study examined differences in acute subjective response to alcohol between African Americans and European Americans. Additionally, we tested if the association between response to alcohol and past month drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems differed across race.

Methods

One hundred and seventy eight participants (mean age = 21.87, SD = 1.23; 57% African American) who were moderate to heavy social drinkers completed an alcohol administration study in a laboratory setting, receiving a moderate dose of alcohol (0.72g/kg alcohol for males, 0.65g/kg for females). Acute alcohol response was measured at 8 time points (i.e., baseline, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes).

Results

Latent growth curve models showed that African Americans experienced sharper increases in stimulation on the ascending limb compared to European Americans. African American women experienced sharper increases in sedation on the ascending limb compared to European American women. Change in sedation on the ascending limb was associated with past month drinking behavior. Stimulation on the ascending limb was related to alcohol-problems for African Americans but not European Americans.

Conclusions

We found differences in response to alcohol across racial groups: African Americans showed a stronger response to alcohol. Future studies are needed to incorporate response to alcohol into a larger model of African American alcohol use.

Keywords: Response to alcohol, African American, Racial Differences, Alcohol Administration

Introduction

A large and growing body of research has focused on response to alcohol as an endophenotype for alcohol use disorders (see Morean and Corbin, 2010; Ray, et al., 2010 for reviews). Cannon and Keller (2006) identify six characteristics for considering whether a variable is a viable endophenotype that will facilitate our understanding of the underlying genetics of a given disorder. Response to alcohol has been shown to meet several of these criteria: response to alcohol has been found to be heritable (Heath and Martin, 1991; Heath et al., 1999; Viken, et al., 2003), differentiate between children of alcoholics and controls (Schuckit, 1985; Schuckit and Gold, 1988), influence risk for alcohol dependence (Schuckit and Smith, 2001) and to relate to increased heavy alcohol use and alcohol related problems in adolescents (e.g., Chung and Martin, 2009) and adults (e.g., Conrod, et al., 2001; Schuckit and Smith, 2000; Schuckit et al., 2007). Response to alcohol has been shown to be related to alcohol use disorders even after controlling for other important risk factors, such as family history of alcoholism (Trim, et al., 2009).

Two separate models of alcohol response have been proposed: the low level of response model (e.g., Schuckit, 1980, 1984; Schuckit and Smith, 2001) and the differentiator model (see Newlin and Thompson, 1990; Newlin and Renton, 2010). The low level of response model is widely studied and has consistently shown that individuals with decreased sensitivity to the sedating effects of alcohol are at increased risk for alcohol use disorders and alcohol-related problems. However, research also suggests that heightened response to alcohol is associated with risk (e.g., Conrod et al., 2001; Conrod, et al., 1995; Finn, et al., 1990). Newlin and Thompson (1990: see also Newlin and Renton, 2010) synthesized these findings by showing that in sons of alcoholics, increased response to alcohol on the ascending limb, when blood alcohol levels are increasing, and dampened response to the sedating effects of alcohol on the descending limb, when blood alcohol levels are decreasing, are related to increased risk. This differentiator model is also supported by studies showing that heavy drinkers experience increased stimulation following alcohol consumption (ascending limb) compared to light drinkers and that heavy drinkers are less sensitive to the sedating effects of alcohol across both the ascending and descending limbs (King, et al., 2011; King, et al., 2002). There is also evidence that subjective stimulation following alcohol consumption is associated with greater alcohol consumption within the drinking event, while subjective sedation is not (Corbin, et al., 2008). A recent meta-analysis directly comparing the support for these two models found that the low level of response model explained differences between individuals with and without a family history or alcoholism whereas the differentiator model was supported when examining typical alcohol consumption patterns (Quinn and Fromme, 2011).

Quinn and Fromme (2011) note the differences in protocol across studies as well as the average sample size being relatively small to detect effects (N = 41) as current limitations of this area of research. Additionally, Morean and Corbin (2010) have previously noted that the majority of research conducted on subjective response to alcohol has focused on the descending limb of the blood alcohol curve. They stress the need for research examining both stimulating and sedating effects conducted across both the ascending and descending limbs to fully test which model of alcohol response (low level of response vs. differentiator model) most accurately reflects this construct. A notable strength of the present study is the significantly larger sample size (N = 178) than the average of the studies identified by Quinn and Fromme (2011) and the examination of both stimulation and sedation across the ascending and descending limbs of the blood alcohol curve, rather than only the descending limb.

Response to Alcohol in Different Racial/Ethnic Groups

While response to alcohol has been studied in Asian (e.g., Luczak, et al., 2002), Native American (Garcia-Andrade, et al., 1997), and Latino (Schuckit, et al., 2004) populations, research on African American response to alcohol has been largely unstudied. Previous findings using the African American portion of the current sample (Pedersen and McCarthy, 2009) found that subjective response to alcohol, both retrospective and acute, had a similar pattern of associations with alcohol use as found in previous research with other racial/ethnic groups. However, our previous work was solely focused on African Americans and did not include a European American comparison sample. The goal of the present study was to provide a direct comparison between this African American sample and a European American sample in their response to alcohol and its associations with alcohol use and problems. Testing differences and similarities in response to alcohol between these two groups is an important next step in understanding some of the complexities of racial differences in drinking behavior and for validating response to alcohol as an endophenotype for alcohol use disorders in African Americans.

Differences in Drinking Behavior for African Americans and European Americans

A growing body of research indicates that there are pronounced differences in drinking behavior for African Americans and European Americans. Interestingly, these differences change across the lifespan, with African American adolescents and young adults engaging in less heavy drinking (Wallace, et al., 2003; Bachman, et al., 1991) and having higher rates of abstinence (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003). While young African Americans are at reduced risk there is also evidence that the differences in alcohol consumption “disappear” by mid-adulthood (e.g., Herd, 1989; Caetano and Kaskutas, 1995). Additionally, while risk for meeting lifetime criteria for an alcohol use disorder is lower for African Americans (Breslau et al., 2006) there is some evidence for increased persistence of alcohol dependence and more frequent engagement in heavy drinking occasions for this group (Dawson, 1998). Epidemiological studies also highlight the possibility of an interaction between race and gender, where the difference in drinking behavior is larger between African American and European American women than men (National Health Interview Survey, 2005).

Specific Aims

The present study had two primary aims. Our first aim was to expand our previous work (Pedersen and McCarthy, 2009) and directly examine whether African Americans and European Americans differed in their acute subjective response to alcohol (stimulation, sedation) following alcohol administration. Research has shown that individuals with at least one copy of ADH1B*3, a genetic polymorphism that affects alcohol metabolism and is found predominantly in people of African descent, have a stronger acute response to alcohol (McCarthy et al., 2010). While we did not examine specific genetic polymorphisms in the current study, we hypothesized, based on this previous genetics research, that African Americans would be more sensitive to both the stimulating and sedating effects of alcohol. Within this aim we also explored potential race X sex interactions in response to alcohol. Given that African American women use the lowest amount of alcohol compared to African American men and European American men and women, we hypothesized that African American women would experience the sharpest increases in sedation following alcohol consumption. Our second aim was to test whether the association between response to alcohol and self-reported drinking behavior differed as a function of race. We hypothesized that while response to alcohol may differ across racial groups, the association between drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems would not differ across race.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 178 young adult moderate to heavy social drinkers. The sample was 47% male and had a mean age of 21.78 (SD = 1.16, range 21–26). Participants were initially recruited into the study based on their identification as either African American or European American/White. One hundred and two participants (57% of the total sample; African American male, n = 46; African American female, n = 56) identified as African American or African American and “more than one race.” Seventy-six participants (43% of the total sample, European American male, n = 37; European American female, n = 39) identified as European American/White or European American/White and “more than one race.” Additionally, the small number of African American participants that identified as “more than one race” (n = 9) or who identified as Hispanic were required to have at least one biological parent who was of African descent. Only one European American participant identified as “more than one race” and at least one of their biological parents was of European descent and neither biological parent was of African ancestry. The majority of the sample (76%) had some college education and 15% reported being college graduates. Participants were required to be between the ages of 21 and 26 years old and to be current drinkers. Additionally, participants were excluded if they were currently an abstaining alcoholic, had significant medical or psychiatric illness (e.g., psychotic disorders, past head injury with loss of consciousness > 5 minutes) or were currently taking medication for which use of alcohol is contraindicated.

Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the University of Missouri’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from the University of Missouri, the city of Columbia, Missouri, and the surrounding area. Fliers were placed at various locations at the University of Missouri and at local businesses. Potential participants received a basic phone screening to determine eligibility.

Participants who met eligibility criteria were scheduled for an interview. On the interview day, participants provided informed consent and completed the interview, study tasks, and questionnaires in a private office. As part of a larger study, African American participants received $40 for their participation in the interview. European Americans completed an abbreviated assessment battery and received $10 for their participation in the interview.

Participants were scheduled for a second appointment approximately one week after the initial interview. They were instructed to refrain from alcohol for 24 hours before the session and to refrain from other drug use for 48 hours. They were also instructed to not eat or drink any fluids other than juice or water (e.g., no caffeinated beverages, dairy products) for 8 hours prior to their session (starting at 12 midnight the evening prior). Participants who were taking medication that is safe to use while consuming alcohol but could affect subjective or physiological assessments (e.g., pseudoephedrine) were asked to not take the medication prior to the alcohol administration session.

The alcohol administration session took approximately five hours. Participants arrived at the laboratory at 8:00 a.m. and a low-fat breakfast was provided. A questionnaire was administered to verify compliance with pre-session instructions. A breath alcohol test was used to verify abstinence from alcohol. Females were given a urine pregnancy test and excluded from the study if they tested positive. One participant was excluded as a result of testing positive on her pregnancy test.

Between 8:30 and 9:00 a.m., baseline measures were taken. At 9:00 a.m., participants received an alcoholic beverage. Participants received a dose of alcohol equivalent to 0.72g/kg alcohol for males, 0.65g/kg alcohol for females, designed to reach a peak blood alcohol concentration of approximately 0.075 to 0.080 mg% (Sher and Walitzer, 1986). The alcohol drinks were made using 50% alcohol (vodka), in 20% solution with non-caffeinated soda (tonic). Beverages were consumed over a 15-minute period.

Participants were assessed prior to beverage consumption, in 15 minute intervals for the first hour following consumption, and 30 minute intervals thereafter. The alcohol administration and assessment were conducted in a private office, with a semi-recumbent chair, separate from that used for interviews. At approximately 12:00 PM after completion of study assessments, each participant was provided lunch. To minimize risk, the following procedures outlined in the NIAAA Recommended Council Guidelines on Ethyl Alcohol Administration in Human Experimentation were used (NIAAA, 2005). Participants were not allowed to leave the laboratory until their observable behavior had returned to normal and until their breath alcohol concentration fell below 0.02%. Each participant was also required to travel home by taxi (provided by the study), or with a friend. Participants were required to state in writing that he or she would not drive a car or operate other machinery for three hours after leaving the laboratory. As part of a larger study, African Americans were reimbursed $100. European Americans completed a reduced assessment battery and were therefore reimbursed $50 for participation in the session.

Measures

Alcohol Use

Past month drinking behavior was assessed using questions modified from the Monitoring the Future project (Johnston, et al., 2010). The first dependent variable was a factor score created using past month quantity, frequency, number of times having 5 or more drinks, and largest number of drinks consumed on one occasion. The Drinking Styles Questionnaire (DSQ: Smith, et al., 1995) was used to provide information on problems perceived to be caused by one's drinking. The second dependent variable, alcohol-related problems, was created by summing 8 true/false items that assessed negative consequences of alcohol use (e.g., experienced legal problems, blackouts). The DSQ contains 10 true/false items that are designed to look at alcohol-related problems (e.g., blackout, trouble with friends, legal problems). We excluded 2 items (felt nauseous, had a hangover) due to lack of variability in our sample (> 80% of participants endorsed these items). The DSQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity in adolescent samples (Smith et al., 1995) and has been used in European American and African American college samples (McCarthy, et al., 2001).

Acute Response to Alcohol

Acute response to alcohol was evaluated at baseline, and at all measurement points following beverage consumption, using the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES: Martin, et al., 1993). This measure assesses separate sedating and stimulating effects of alcohol on both the ascending and descending limb of the blood alcohol curve (type of response×blood alcohol curve limb: Earleywine and Erblich, 1996).

Breath Alcohol Concentration (BrAC)

Breath alcohol readings were taken using a breathalyzer device (Intoximeters, inc.) at baseline and at seven time points after consumption of the beverage. Peak BrAC for the full sample was at 60 minutes following alcohol consumption (Mean = .071). African Americans and European Americans did not differ in BrAC at any time point except the final assessment (150 minutes post alcohol consumption). At this assessment African Americans had a higher BrAC than European Americans (t = 3.16, p < 01; African American BrAC = .054 vs. European American BrAC = .048).

Data Analytic Plan

Subjective response to alcohol was assessed at 8 different time points. To account for the nesting of multiple assessments within person, a latent variable growth model using Mplus 6.12 (Muthén and Muthén, 2011) was used to examine this risk factor. Models were estimated using a robust maximum likelihood estimator, and model fit was assessed using the Chi-square goodness of fit test, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). For the CFI and TLI, we used the conventional cutoff values .90 or greater for acceptable fit, and .95 or greater for good fit (McDonald and Ho, 2002). Models were fit separately for the ascending (pre-drink, 15, 30, and 45 minutes post drinking) and descending (60, 90, 120, 150 minutes post drinking) limbs of the BrAC curve based on peak BrAC indicating the beginning of the descending limb.

Separate models were run for stimulation and sedation on the ascending and descending limbs of the blood alcohol curve. Time was coded so that the intercept reflected the model implied baseline assessment (pre-drinking assessment for ascending limb, 60-minutes post drinking for descending limb). These models controlled for race, sex, and BrAC (45 minutes post-drinking for ascending limb analyses, 60 minutes post-drinking for descending limb analyses). Race and sex were used as control variables for both the intercept and slope parameters, while BrAC and the model implied intercept were used as control variables for the slope parameter. The fit indices for these base models indicated at least adequate fit for all models (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Model fit indices for base models

| Chi-Square | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending Limb | |||

| Stimulation | 26.92, p < .01 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| Sedation | 24.36, p < .05 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Descending Limb | |||

| Stimulation | 18.71, p < .05 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Sedation | 30.09, p < .01 | 0.95 | 0.91 |

Results

Differences in Drinking Behavior

T-tests were used to test mean level racial differences in drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems. European Americans reported higher levels of all measures of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems (see Table 2). Males reported significantly higher past month alcohol use compared to females. Males and females did not differ in number of alcohol-related problems. The pattern of sex differences did not differ between African American and European American groups.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Alcohol Use Behavior

| African Americans | European Americans | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 5.98 (5.38) | 9.64 (5.44)*** |

| Quantity | 3.05 (1.67) | 4.99 (2.75)*** |

| 5 + Drinks | 2.26 (3.08) | 5.12 (4.35)*** |

| Largest Number of Drinks | 5.48 (3.88) | 9.68 (4.64)*** |

| Alcohol-related Problems | 1.36 (1.43) | 2.88 (1.74)*** |

Note. Values are means and standard deviations of raw scores. T-tests were used to compare mean level differences between African Americans and European Americans.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Race and Sex Differences in Response to Alcohol

Stimulation

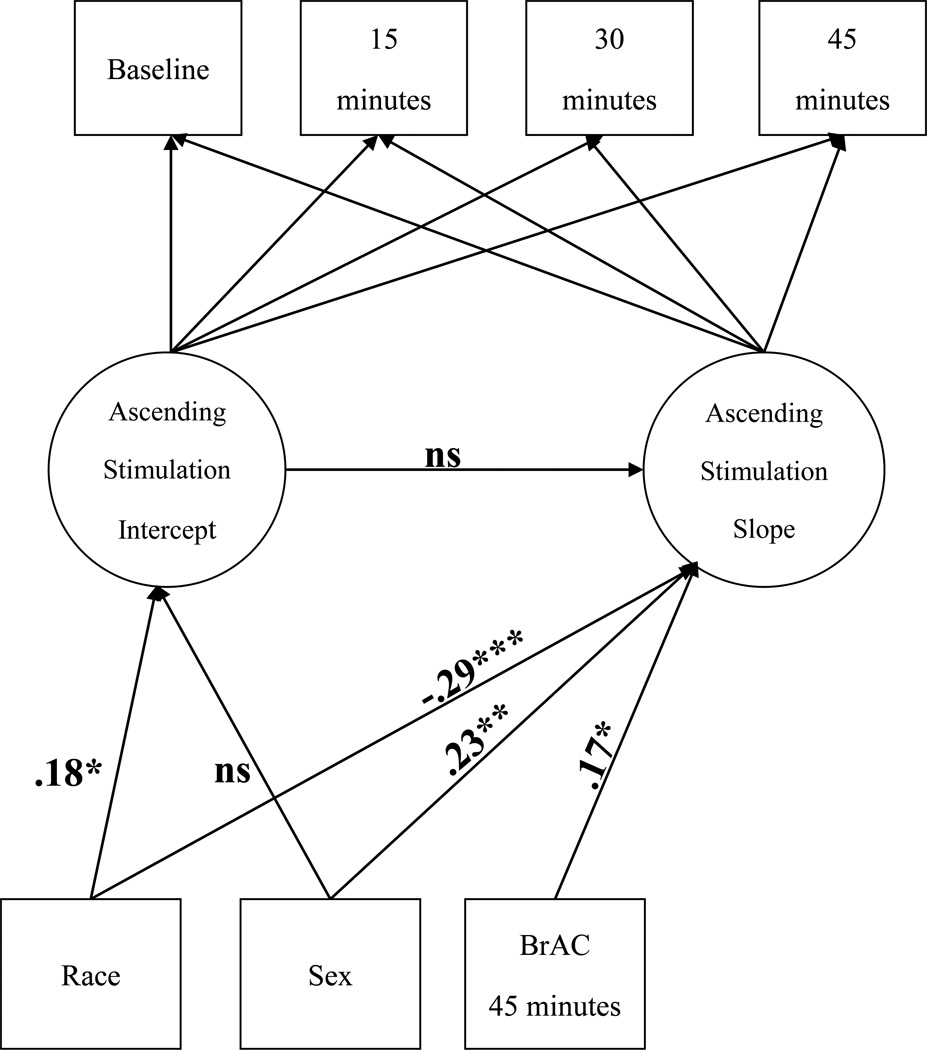

The first aim of our study was to test differences between African Americans and European Americans in their acute response to alcohol. Race was significantly related to the intercept (β = .18, p < .05) and slope parameters (β = −.29, p < .001) of stimulation on the ascending limb. European Americans had higher baseline levels of stimulation while African Americans experienced sharper increases in stimulation across the ascending limb (see Figure 1). Males also experienced increased growth in stimulation compared to females on the ascending limb (β = .23, p < .01). However, race and sex did not interact to predict changes in stimulation on the ascending limb (β = −.20, p = .07). Race was not related to the intercept (β = −.01, p = .95) or slope (β = .04, p = .59) parameters of stimulation on the descending limb. Sex was related to the intercept parameter (β = .17, p < .05), indicating that males had higher levels of stimulation 60 minutes following alcohol consumption. The interaction between race and sex was not a significant predictor of change in stimulation on the descending limb (β = .02, p = .72).

Figure 1.

Latent Growth Curve Model of Racial Differences in Stimulation on the Ascending Limb. (Figure depicts a latent growth curve model of growth in stimulation on the ascending limb of the blood alcohol curve. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; Standardized coefficients are presented. Race was coded: African Americans = 0, European Americans = 1. Sex was coded: Females = 0, Males = 1.)

Sedation

For sedation on the ascending limb, European Americans reported higher baseline levels (β = .24, p < .05), but racial differences were not found for the growth parameter (β = −.15, p = .25). Females experienced increased growth in sedation compared to males on the ascending limb (β = −.39, p < .001). However, this was qualified by an interaction between race and sex (β = .39, p < .01). Follow-up analyses run separately within male and female groups indicated that African American females showed marginally increased growth in sedation on the ascending limb compared to European American females (β = −.63, p = .13) while African American males showed marginally slower growth in sedation compared to European American males (β = .22, p = .10). Race was not related to the intercept (β = .04, p = .58) or growth (β = .02, p = .76) parameters of sedation on the descending limb. Sex was related to the intercept parameter (β = −.22, p < .01) indicating that females had higher levels of sedation 60 minutes following alcohol consumption compared to males. The interaction between race and sex was not a significant predictor of change in sedation on the descending limb (β = −.03, p = .76).

Controlling for Alcohol Use Differences

While we interpret our findings in line with theories of response to alcohol predicting later alcohol use, an alternative interpretation of these findings could be that racial differences in recent alcohol use resulted in racial differences in acute response to alcohol. African Americans consume less alcohol, which could result in group differences in acute sensitivity to alcohol (e.g., stimulation). To address this possibility and more stringently test racial differences in response to alcohol, we ran models controlling for four facets of past month alcohol use (quantity, frequency, frequency of 5 or more drinks, and maximum drinks consumed in on one occasion). Controlling for differences in recent alcohol use allows us to tease apart if the findings presented above are a result of differences in alcohol use across races or “true” differences in subjective response to alcohol. The pattern of results remained unchanged when controlling for recent alcohol use: African Americans experienced a sharper increase in stimulation on the ascending limb compared to European Americans (β = −.31, p < .001). Additionally, a significant sex X race interaction remained for sedation on the ascending limb (β = .39, p < .01). These findings suggest that racial differences in subjective response to alcohol are not an artifact of differences in recent alcohol use behavior.

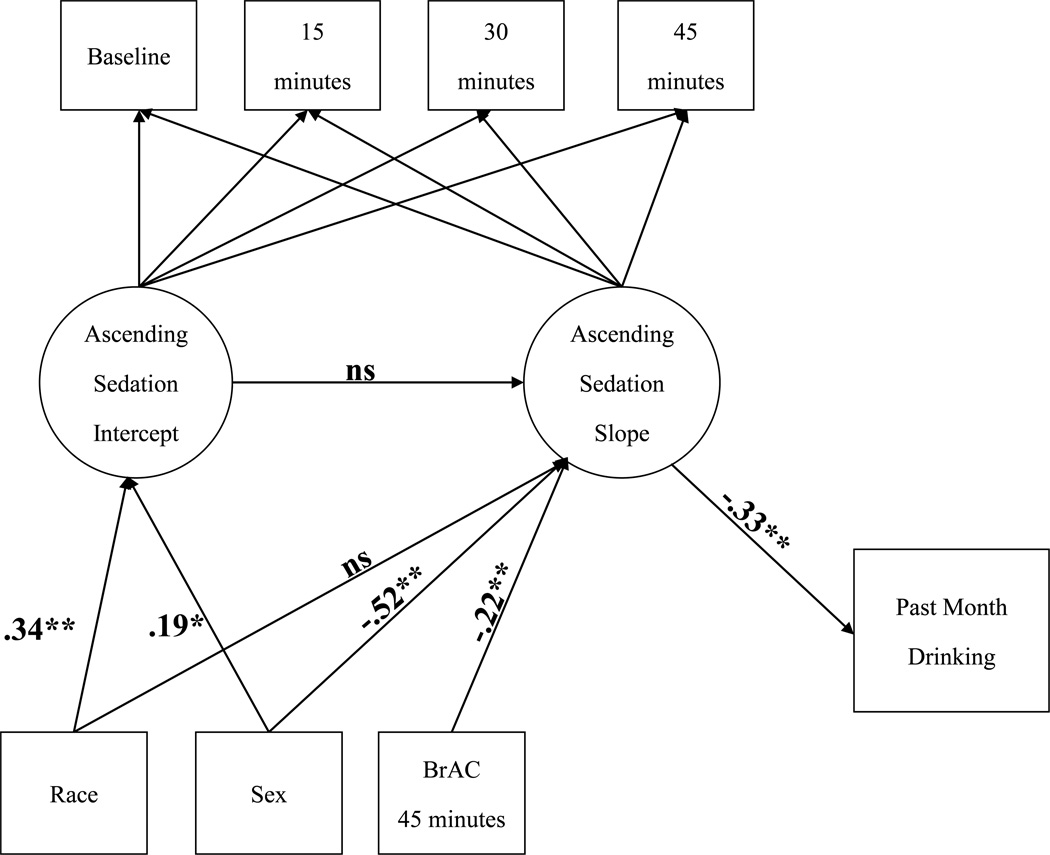

Alcohol Response Predicting Drinking Behavior

We next examined changes in acute response on the ascending and descending limbs of the blood alcohol curve as a predictor of past month drinking and alcohol-related problems. Sharper increases in sedation on the ascending limb was related to lower levels of past month drinking behavior (β = −.33, p < .001; see Figure 2).The slopes of sedation on the descending limb and stimulation on either the ascending or descending limbs were not significantly related to alcohol use behaviors for the full sample. A significant interaction between race and stimulation on the ascending limb was found, with greater increases in simulation associated with experiencing more alcohol-related problems for African Americans (β = .23, p < .05). For European Americans, the opposite pattern was found, greater increases in stimulation was marginally associated with experiencing fewer alcohol-related problems (β = −.21, p = .08).

Figure 2.

Latent Growth Curve Model of Sedation on the Ascending Limb Predicting Past Month Alcohol Use. (Figure depicts a latent growth curve model of sedation on the ascending limb of the blood alcohol curve predicted past month alcohol use. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; Standardized coefficients are presented. Race was coded: African Americans = 0, European Americans = 1. Sex was coded: Females = 0, Males = 1.)

Discussion

Response to alcohol has been studied extensively as a risk factor, and potential endophenotype, for alcohol use disorders and has been examined across several different racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Native American, European American, Asian). However, research on African American response to alcohol has been limited and has not directly compared African American and European American response to alcohol. This is an important next step to gain understanding about an important risk factor for heavy alcohol use in an understudied population. The current study examined if European Americans and African Americans differed in their acute subjective response to alcohol and if subjective response to alcohol was differentially associated with alcohol use behaviors across racial groups.

Our results found significant differences between African Americans and European Americans on the ascending but not descending limb of the breath alcohol curve. African American females experienced greater sedation on the ascending limb, a pattern that was associated with lower rates of alcohol use and alcohol problems for the full sample. The increases in sedation experienced by African American women immediately following alcohol consumption may partially explain why, compared to European American women, African American women consume significantly less alcohol (National Health Interview Survey, 2005). However, African Americans in this sample also exhibited greater increases in stimulation on the ascending limb, and this increase was associated with increased alcohol-related problems. Our results for heightened stimulation early in the drinking period are consistent with results from Kerr and colleagues (2006), who demonstrated that African Americans, particularly individuals under 30 years of age, reported needing fewer drinks to feel “drunk” compared to European Americans. Taken together these findings may indicate that African Americans are more sensitive to the effects of alcohol.

Finding evidence for both decreased and increased risk in the African Americans in our sample is consistent with the complex differences in drinking behavior observed between African Americans and European Americans in the larger body of literature. For example, while African Americans have higher abstention rates (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003) they also may engage in more frequent binge drinking and be more likely to persist in alcohol use disorders (Dawson, 1998), and experience more negative consequences from drinking (Mulia, et al., 2009) compared to European Americans. These findings highlight the possibility that acute stimulation may play a role in the “risky drinking” seen in African American drinkers compared to European American drinkers. Future longitudinal research could directly test this possibility to examine how stimulation is related to a wider range of drinking outcomes (e.g., onset to alcohol use disorder) over time across racial groups.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has several limitations that impact the conclusions that can be drawn. As with all alcohol administrations, all of our participants were required to be current drinkers and at least 21 years of age. This decreases the generalizability of our sample by restricting the range of alcohol use (e.g., excluding abstainers, light drinkers), particularly when examining racial differences in a risk factor for alcohol use, which may have inadvertently restricted the range in this construct as well. Recent work by Noel and colleagues (2011) highlighted the importance of considering racial differences in alcohol use and psychopathology when recruiting for alcohol administrations with African Americans. While we controlled for differences in recent alcohol use when examining racial differences in response to alcohol, we did not match participants across race on drinking and other variables that may play a role in drinking behavior. This type of design approach has regularly been utilized in studies on response to alcohol that examine group differences (e.g., family history positive vs. family history negative). For example, King and colleagues (2011) compared response to alcohol in light vs. heavy drinkers. Future research using questionnaire measures of response to alcohol (e.g., the Self-Rating Effects of Alcohol scale: Schuckit, et al., 1997) could examine racial differences in response to alcohol in adolescence as individuals onset to drinking and in a wider range of drinkers (e.g., light drinkers, occasional drinkers). Additionally, while we assessed four facets of alcohol use behavior, utilizing a more detailed measurement of recent drinking behavior such as the timeline follow back (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) may allow for a more complete way of controlling for and understanding drinking differences between group.

Additionally, in order to maximize sample size, the current study did not utilize a placebo beverage condition which makes it difficult to disentangle expectancy effects about alcohol vs. actual response to alcohol. Therefore, another possible interpretation of our findings is that observed racial differences in alcohol response are due to differences in expectancies between groups, rather than the pharmacological effects of alcohol. However, while not as stringent a test as a placebo design, supplementary analyses (not presented) controlling for positive and negative alcohol expectancies (CEOA; Fromme et al., 1993) did not change the pattern of results. Research has also shown differences across race in regards to beverage preference: African Americans are more likely to consume liquor compared to European Americans (Bluthenthal, et al., 2005). In the current study participants consumed vodka with tonic, so racial differences in beverage preference/familiarity may have influenced results. Future alcohol administrations could employ a balanced placebo design and vary the beverage consumed to see if results are replicated.

Implications

The current study is the first to our knowledge to compare African American and European American response to alcohol. Importantly, our results were consistent when controlling for recent alcohol use and positive and negative alcohol expectancies. Findings show that acute stimulation may play an important role in African American drinking and may explain some of the complexities in the racial differences in alcohol use between African Americans and European Americans. For example, African Americans may be more likely to abstain from alcohol use for contextual reasons (e.g., cultural norms) and yet among drinkers may be more likely to engage in binge drinking episodes compared to European Americans because they experience increased stimulation after consuming alcohol. Additionally, this study highlights the need for further research that integrates multiple risk and protective factors, to explore the nuanced differences in alcohol use behavior between these racial groups.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants (R21 AA015218; T32 AA13526; F31 AA017571; T32 AA007435) from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Contributor Information

Sarah L. Pedersen, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

Denis M. McCarthy, Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Missouri

References

- Bachman JG, Wallace JM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Kurth CL, Neighbors HW. Racial/ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American high school seniors, 1976–89. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Taylor DB, Guzman-Becerra N, Robinson PL. Characteristics of malt liquor beer drinkers in a low-income, racial minority community sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:402–409. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156118.74728.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36:57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Kaskutas L. Changes in drinking patterns among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, 1984–1992. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:558–565. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Keller MC. Endophenotypes in the genetic analyses of mental disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:267–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS. Subjective stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol during early drinking experiences predict alcohol involvement in treated adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:660–667. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Peterson JB, Pihl RO. Reliability and validity of alcohol-induced heart rate increase as a measure of sensitivity to the stimulant properties of alcohol. Psychopharmacology. 2001;157:20–30. doi: 10.1007/s002130100741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Ditto B. Autonomic reactivity and alcohol-induced dampening in men at risk for alcoholism and men at risk for hypertension. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:482–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Gearhardt A, Fromme K. Stimulant alcohol effects prime within session drinking behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Beyond Black, White and Hispanic: Race, ethnic origin and drinking patterns in the United States. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10:321–339. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine M, Erblich JA. Confirmed factor structure for the biphasic effects of alcohol scale. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 1996;4:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Zeitouni NC, Pihl RO. Effects of alcohol on psychophysiological hyperreactivity to nonaversive aversive stimuli in men at high risk for alcoholism. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:79–85. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D’Amico EJ. Measuring adolescent alcohol outcome expectancies. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14:206–212. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot E, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychol Assessment. 1993;5:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Andrade C, Wall TL, Ehlers CL. The firewater myth and response to alcohol in Mission Indians. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:983–988. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Martin NG. Intoxication after an acute dose of alcohol: an assessment of its association with alcohol consumption patterns by using twin data. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, Slutske WS, Bierut LJ, Rohrbaugh JW, Statham DJ, Dunne MP, Whitfield JB, Martin NG. Genetic differences in alcohol sensitivity and the inheritance of alcoholism risk. Psychol Med. 1999;29:1069–1081. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. The epidemiology of drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems among US Blacks. (DHHS Publication No. ADM 89-1435) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1989. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Intoximeters, inc. St. Louis, MO, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009 (NIH Publication No. 10-7583) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Midanik LT. How many drinks does it take for you to feel drunk? Trends and predictors of subjective drunkenness. Addiction. 2006;101:1428–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, stimulant, and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:389–399. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Houle T, de Wit H, Holdstock L, Schuster A. Biphasic alcohol response differs in heavy versus light drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:827–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Elvine-Kreis B, Shea SH, Carr LG, Wall TL. Genetic risk for alcoholism relates to level of response to alcohol in Asian-American men and women. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty R, Perrine M, Swift R. Development and validation of the biphasic effects of alcohol scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Miller TL, Smith GT, Smith JA. Disinhibition and expectancy in risk for alcohol use: comparing black and white college samples. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:313–321. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MH. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR. Subjective response to alcohol: A critical review of the literature. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen and Muthen; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Recommended council guidelines on ethyl alcohol administration in human experimentation. Maryland: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Interview Survey. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/DatabaseResources/QuickFacts/AlcoholConsumption/dkpat26.htm.

- Newlin DB, Renton RM. High risk groups often have higher levels of alcohol response than low risk: The other side of the coin. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:199–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB, Thompson JB. Alcohol challenge with sons of alcoholics: A critical review and analysis. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:383–402. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel NE, Maisto SA, Ogle RL, Johnson JD, Jackson LE, Sims CM. A comparison of African-American versus Caucasian men screened for an alcohol administration laboratory study: Recruitment and representation implications. Addict Behav. 2011;36:536–538. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM. An examination of subjective response to alcohol in African Americans. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:288–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Subjective Response to Alcohol Challenge: A Quantitative Review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1759–1770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Mackillop J, Monti PM. Subjective responses to alcohol consumption as endophenotypes: Advancing behavioral genetics in etiological and treatment models of alcoholism. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1742–1765. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Self-rating of alcohol intoxication by young men with and without family histories of alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1980;41:242–249. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Subjective responses to alcohol in sons of alcoholics and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:879–884. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790200061008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Ethanol-induced changes in body sway in men at high alcoholism risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:375–379. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790270065007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Gold EOA. Simultaneous evaluation of multiple markers of ethanol/placebo challenges in sons of alcoholics and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:211–216. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800270019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The relationships of a family history of alcohol dependence, a low level of response to alcohol, and six domains of life functioning to the development of alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:827–835. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The clinical course of alcohol dependence associated with a low level of response to alcohol. Addiction. 2001;96:903–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96690311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Hesselbrock V, Bucholz KK, Chan G. The ability of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) scale to predict alcohol-related outcomes five years later. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:371–378. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Kalmijn J. Findings across subgroups regarding level of response to alcohol as a risk factor for alcohol use disorders: A college population of women and Latinos. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1499–1508. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000141814.80716.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Tipp JE. The self-rating of the effects of alcohol (SRE) form as a retrospective measure of the risk for alcoholism. Addiction. 1997;92:979–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS. Individual differences in the stress-response-dampening effect on alcohol: a dose-response study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95:159–167. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/DatabaseResources/QuickFacts/AlcoholConsumption/dkpat2.htm.

- Trim RS, Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The relationships of the level of response to alcohol and additional characteristics of alcohol use disorders across adulthood: a discrete-time survival analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viken RJ, Rose RJ, Morzorati SL, Christian JC, Li T. Subjective intoxication in response to alcohol challenge: Heritability and covariation with personality, breath alcohol level, and drinking history. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:795–803. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000067974.41160.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]