Abstract

Objectives

Etanercept blocks tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), a proinflammatory cytokine that plays a role in cancer-related cachexia and tumor growth. A phase I/II study was conducted to assess the tolerability and efficacy of gemcitabine and etanercept in advanced pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Twenty-five patients received etanercept 25mg subcutaneously twice-weekly with gemcitabine. A control cohort of 8 patients received gemcitabine alone. The primary end-point was progression-free survival (PFS) at 6 months. Blood specimens were analyzed for TNF, IL-1b, IL-6, interferon-γ, IL-10, and NF-kB activation. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00201838.

Results

Thirty-eight patients participated in this study. In the gemcitabine-etanercept cohort, grade 3/4 drug-related toxicities included leucopenia (3) and neutropenia (6). There were 3 (12%) patients with partial response and 8 (32%) patients with stable disease. The rate of PFS at 6 months was 28% (n=7; 95% CI 20–36%). Median time to progression was 2.23 months (95% CI, 1.86–4.36 months) and median overall survival was 5.43 months (95% CI, 3.30–10.23 months). Clinical benefit rate was 33% of the evaluable patients. A correlation was seen between IL-10 levels and clinical benefit.

Conclusions

Etanercept added to gemcitabine is safe but did not show significant enhancement of gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: etanercept, pancreatic cancer, cancer-related cachexia

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. Fifty-three percent of the patients are typically diagnosed with metastatic disease on presentation, for which the 5-year survival rate is a dismal 1.8%.1 Patients with pancreatic cancer are also disproportionably debilitated by cachexia, which is characterized by anorexia and loss of both adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Cancer-related cachexia is thought to be induced by proinflammatory cytokines which stimulate fat and protein degradation, and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) have all been found to be elevated in pancreatic cancer patients.2,3

TNF is a cytokine that is secreted by tumor cells and macrophages in response to infection and tumor invasion. It has been found to increase lipolysis and suppress transcription factors necessary for adipocyte differentiation.4,5,6 TNF activates NF-kB, which in turn promotes muscle cell turnover.7 Two genes, MAFbx and MuRF1, which are ubiquitin ligases, were found to be upregulated in in vivo models of muscle atrophy.8 Activated NF-kB has been demonstrated to upregulate MuRF1.9 Interestingly, activated NF-kB also increases cellular resistance to apoptosis.10 TNF has been shown to increase invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro, and enhance tumor growth and metastasis in mice bearing orthotopic pancreatic cancers.11 Anti-TNF therapy with etanercept or infliximab reduced tumor growth and metastasis in these mice. Etanercept is a recombinant human TNF that specifically binds and renders soluble TNF biologically inactive by blocking their interaction with cell surface TNF receptors. It has been used with significant clinical responses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory conditions in which TNF is implicated.12,13,14

In this study, we hypothesized that effective inhibition of TNF with etanercept may decrease cancer-related cachexia and enhance the activity of chemotherapy. We proposed combining etanercept with gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, with the aim of increasing progression-free survival at 24 weeks and improving clinical benefit response (CBR) as a secondary endpoint. In addition, we examined serial serum levels of TNF, IL-1b, IL-6, interferon-γ (IFN), and IL-10, and activation of NF-kB to explore treatment effect on the cytokines.

Patients and Methods

The study was conducted at the Ohio State University and Mark H Zangmeister Center, and approved by the Ohio State University institutional review board.

Eligibility

Eligible patients were required to have histologically or cytologically confirmed unresectable pancreatic cancer, measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), no prior systemic therapy; patients with prior chemoradiation were >3 months from their last dose of 5-Fluorouracil if used as a radio-sensitizer and >4 weeks from their last dose of radiation.15 Additional criteria included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status of <2 and a predicted life expectancy of >12 weeks. Strict criteria for study entry was that patients must have at baseline: 1) pain intensity as measured by Memorial Pain Assessment Card of >10mm on a 100mm scale, stable for at least one week and 2) any analgesic consumption, as long as it is stable for at least one week. Patients were required to have normal organ function, and to be free of any serious, active infection and of another malignancy for > 5 years with the exception of basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma of the skin or carcinoma in situ of the cervix. Patients with brain metastases were not eligible for the study. Additionally, patients who had prior exposure to gemcitabine or etanercept, or had known sensitivity to either drug were excluded from the study.

Study design

This Phase I/II open-label study was conducted at The Ohio State University and the Mark H Zangmeister Center. Informed consent was obtained from each subject before their participation in the study. An abbreviated phase I study was conducted to ensure that the combination of gemcitabine and etanercept at the specified doses could be safely administered. Six patients in the abbreviated phase I cohort were entered at (and eventually included in) the planned phase II dose level to assess any unexpected adverse events. Adverse events were defined as grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicity or prolonged grade 2 non-hematologic toxicity with the exception of mucositis, diarrhea, or nausea/vomiting relieved with anti-emetics. Dose modifications for expected toxicities to gemcitabine were as per standard. If 2 or more patients at the initial dose experienced an unexpected adverse event, the dose of gemcitabine was to be lowered by 25% and 6 patients would be entered at that dose level. If 1 or fewer patients encountered unexpected adverse events, we would then proceed at that dose level for the phase II portion of the trial.

The primary objective of the phase II portion of the study was to evaluate the anti-tumor effect as measured by the proportion of patients free of disease-progression at 6 months after treatment. The sample size for the phase II study was 25 patients, including the 6 patients at the phase II dose level in the phase I study. At the completion of the cohort of 25 patients with gemcitabine and etanercept, we had a planned “control” group of 10 patients who received gemcitabine alone. Blood samples for the correlative work described below were required from all patients. Secondary objectives included evaluation of toxicities, CBR, median overall survival (mOS), median progression-free survival (mPFS) and peripheral blood measurement of cytokines: TNF, IL-1b, IL-6, IFN, IL-10, IL-12 and NFkB.

Gemcitabine administration and dose modification

The starting dose of gemcitabine was an intravenous infusion of 1000mg/m2 over 30 minutes, weekly × 7 with a one-week rest followed by 1000 mg/m2 weekly × 3 with one-week rest for the remainder of treatment. There were 3 levels of dose reductions planned (25%, 50%, and 75% reduction relative to the previous dose) for hematological and non-hematological toxicities. Steroids were not permitted for anti-emetic prophylaxis during the first course of therapy due to possible alteration of the biologic correlates.

Etanercept administration and dose modification

Etanercept was self-administered by patients at a fixed dose of 25 mg subcutaneous injections twice-weekly starting seven days prior to gemcitabine administration and continued throughout the study period. Etanercept was held if sepsis or neutropenic fever was demonstrated, with no dose modifications. It was discontinued if there was evidence of allergic reactions.

Assessment of response and toxicity

Tumors were assessed by CT scans at week 12, and every 8 weeks thereafter, and response and progression were evaluated according to the RECIST criteria.15 Toxicities were graded according to the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0. As previously published, CBR was measured by change in pain intensity, analgesic consumption, ECOG performance status, and weight.16

Molecular correlates

Blood samples were drawn prior to the first etanercept infusion, prior to and after the first infusion of gemcitabine, and before gemcitabine infusions in weeks 4 and 7. Intracellular levels of TNF, IL-1b, IL-6, IFN, IL-10, and IL-12 were determined, and the activation of NF-kB. TNF can stimulate the expression of IL-1b, IL-6, and itself through activation of NF-kB. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, and thus levels may change with alteration in the proinflammatory TNF levels. Increased IFN levels have also been observed in cancer cachexia. Procedure for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for TNF, IL-1b, and IL-6 has been previously described.17 Post-treatment levels of TNF were measured after etanercept-bound TNF was removed from the serum.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions (5’-Nuclease TaqMan Assay; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for human IFN, TNF, IL-1b, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12 transcripts were performed as singleplex reactions with primer and probe sets specific for the cytokine transcript of interest and an 18s RNA endogenous control. Reactions were performed using an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Taqman; Applied Biosystems). Data was analyzed according to the comparative concentration threshold method, using endogenous control (18s RNA) transcript levels to normalize differences in sample loading and preparation as previously described.18,19 NF-kB activation was measured through a commercially available ELISA (Active Motif, Carlsbad CA) as previously described.4 The same cytokines were assessed at the same time-points with the patients in the “control” group.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint of the trial was disease-free progression at 6 months. A total of 25 patients were needed to estimate a 95% confidence interval for the proportion of disease-free progression with a half width of +/− 20%. The exact binomial probability was used to estimate this sample size. If 7 or fewer of the 25 evaluable patients were progression-free at 6 months, we would have concluded that the combination of etanercept and gemcitabine was not effective in resulting in at least 45% of patients free of tumor progression at 6 months with a probability of less than 0.10. If 8 or more patients were progression-free at 6 months, we would have recommended that the combination be studied further in a randomized phase III trial. Secondary endpoints were evaluated using descriptive statistics due to the limited sample size. Log-rank test was used to compare mOS and mPFS.

Linear mixed effect models were used as an exploratory method to describe the changes of cytokines and NF-κB over time and summarize these changes between the two groups (treatment and control). The model included a subject random effect and also adjusted for the differences in baseline values of each patient. Summary statistics are presented for overall means and counts, differences between second time and last time points minus the first sample after treatment, and also stratified by best response and CBR. The cytokine data were all measured using RT-PCR and normalized using the Ct delta method. PROC MIXED in SAS™, version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC was used.

Results

Patient characteristics

Thirty-eight patients were enrolled between the dates of July 2001 and October 2006, with 30 patients in the experimental cohort and 8 patients in the control cohort. Patient characteristics are included in Table 1. Nine patients were enrolled in the phase I portion of the trial. Three of those patients were determined to be non-evaluable due to unrelated events prior to determining DLT (death due to brain aneurysm unrelated to study drugs, cardiovascular accident prior to receiving the study drugs, and biliary obstruction prior to receiving study drugs). Of the 6 patients who were evaluable for DLTs as defined, 1 patient was removed from study due to acute myocardial infarction thought to be unrelated to drug. The rest did not have any unexpected toxicities as previously defined.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

| Characteristics | Experimental Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| N | 30* | 8^ |

| Male | 16 | 3 |

| Female | 14 | 5 |

| Age | ||

| Range | 46–81 | 46–75 |

| Median | 59 | 59 |

| Metastatic Site | ||

| Liver only | 16 | 0 |

| Liver + other | 10 | 6 |

| Other | 4 | 2 |

| Performance Status | ||

| 0 | 7 | 3 |

| 1 | 21 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 |

5 patients were considered non-evaluable for the primary endpoint

2 patients were considered non-evaluable for the primary endpoint

Next, 21 patients were recruited for the continuation of the phase II portion of the clinical trial. Two patients were considered non-evaluable for disease response due to withdrawal of consent prior to any treatment (1) and non-compliance (1). Only 8 of the 10 patients planned for the “control” cohort were recruited. This was due to the timely approval of erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer, which halted accrual of patients to the gemcitabine monotherapy arm. Two of the 8 patients in the control cohort were non-evaluable for disease response due to patient withdrawal and another patient having no baseline imaging for comparison. Overall, of the 38 patients enrolled on this study, 31 were evaluable for objective response, 37 were evaluable for toxicity and survival analysis, and 17 patients were evaluable for CBR.

Treatment toxicity

The abbreviated Phase I study demonstrated the safety of the drug combination in 6 patients that were considered evaluable for toxicity. The most common toxicities in the combination treatment cohort included anemia, leucopenia, fatigue, nausea, and dysguesia, summarized in Table 2. Grade 3 or 4 toxicities included anemia (1), leucopenia (3), neutropenia (6), thrombocytopenia (1), febrile neutropenia (1), and nausea (1). Ten patients had missed doses due to toxicities, and 11 patients had dose reductions. In the single-agent gemcitabine cohort, the Grade 3 or 4 toxicities noted were: anemia (3), neutropenia (2), and thrombocytopenia (3).

Table 2.

Hematologic and Non-Hematologic Toxicities

| Experimental Group (N=29)* | Control Group (N=8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicities | All Grades | Grades 3 or 4 |

All Grades | Grades 3 or 4 |

| Hematologic | ||||

| Anemia | 20 | 1 | 7 | 3 |

| Leukopenia | 12 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Neutropenia | 9 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 8 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Hematologic | ||||

| Fatigue | 14 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Nausea | 14 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Constipation | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Transaminases | 8 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Diarrhea | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mucositis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Edema | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alopecia | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Injection Reaction | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chills | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

1 patient was not evaluable for toxicity

Treatment efficacy

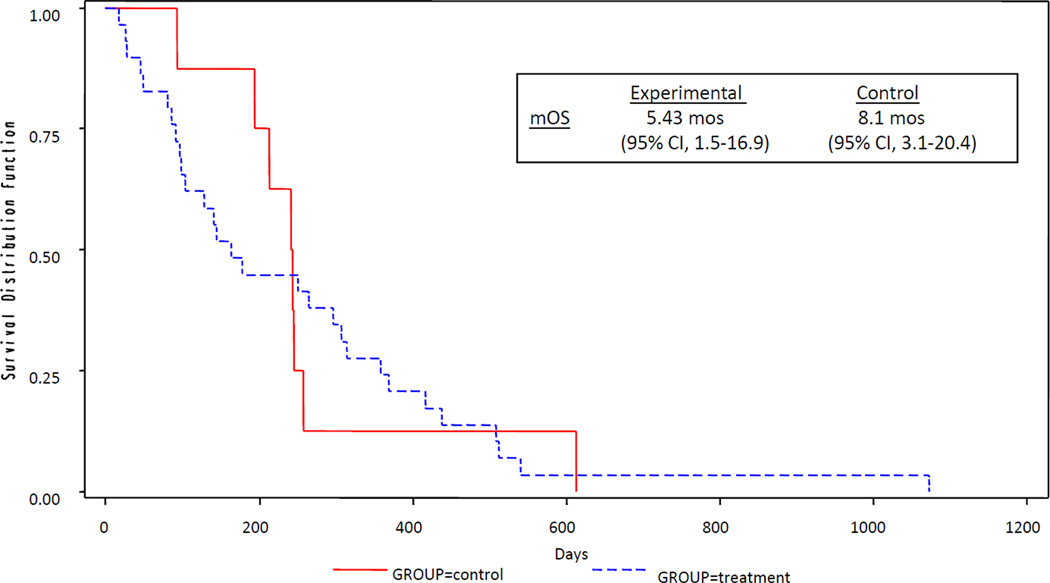

In the experimental cohort, patients underwent a mean of 12.2 weeks of treatment with gemcitabine-etanercept (range 2–40 weeks). In the control group, a mean of 12.8 weeks of gemcitabine was administered (range 8–22 weeks). For the determination of treatment efficacy in the experimental cohort, 20 patients were evaluable for CA19-9 response, 15 patients for CBR, 25 patients for PFS at 6 months and time to progression, and 29 patients for survival analysis. Of the evaluable patients receiving the combination therapy, 3 (12%) had a partial response and 8 (32%) patients had stable disease. Fourteen (78%) patients had a greater than 25% decrease in CA19-9 levels from baseline. Rate of PFS at 6 months was 28% (n=7; 95% CI, 20%-36%). The mTTP was 2.23 months (95% CI, 1.86 –4.36 months) and mOS was 5.43 months (95% CI, 3.30–10.23 months). CBR was observed in 33% of evaluable patients. (Table 3, Figs 1 and 2)

Table 3.

Efficacy Results

| Control Group | Experimental Group | |

|---|---|---|

| CA19-9 Responsea | ||

| N | 8 (100%) | 20 (100%) |

| ≥25% | 3 (42%) | 14 (78%)* |

| CBRn | 0% | 33% |

| %PFS @ 24 weeksc | 1 (14%) | 7 (28%) (95% CI, 20–36%) |

| 1 year OSd | 1 (14%) | 6 (24%) |

| mTTPc | 4.3 mos (95% CI, 2.2–8.1 mos) |

2.23 mos# (95% CI, 1.86–4.36 mos) |

| mOSd | 8.1 mos (95% CI, 3.1–20.4 mos) |

5.43 mos+ (95% CI, 3.30–10.23 mos) |

For the experimental group, 10 patients had CA19-9 levels < upper limit of normal and were not included in the denominator

15 patients were assessable for CBR in the experimental group and 2 in the control group.

For the experimental group, 25 patients were considered evaluable and 6 for the control group

For the experimental group, 29 patients were considered evaluable and 8 for the control group

p=0.728,

p=0.61,

p=0.90

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for Median Time to Progression (mTTP)

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for Median Overall Survival (mOS)

In the control cohort, 8 patients were evaluable for CA19-9 response, 2 patients for CBR, 6 patients for PFS rate at 6 months and time to progression, and 8 patients for 1 year OS and mOS. Three (42%) patients had a greater than 25% decrease in CA19-9. The PFS rate at 6 months was 14% (n=1). In addition, for the patients who received single-agent gemcitabine, 1 (17%) patient had a partial response, and 3 (50%) patients had stable disease. mTTP was 4.3 months (95% CI, 2.2–8.1 months) and mOS was 8.1 months (95% CI, 3.1–20.4 months). CBR was not observed in any of the evaluable patients. (Table 3, Figs 1 and 2)

Correlative studies

Blood samples were available for 26 of the 38 (68%) patients, with a total of 99 observations. There were 6 patients with 18 observations from the control group and 20 patients with 81 observations from the treatment group. Attempts were made to retrieve samples of all the cytokines across the 4 time-points and across the control and treatment groups, however sample collection was unfortunately missing at some time-points. In the analysis comparing cytokine levels between 1st and 2nd samples there were samples from 13 patients in the experimental group and 6 patients in the control group. In the analysis comparing 1st and last samples, there were samples from 17 patients in the treatment group and 5 patients in the control group.

A statistically significant difference was only noted for IL-10 levels in the first sample (prior to the first dose of etanercept) and second sample (after etanercept administration but prior to the first dose of gemcitabine) in the control vs. treatment patient group who had SD or PR, 3.83 vs. 0.66 (p=0.02), respectively. The significance of this finding is limited by the small number of patients included in this analysis (n= 2 in the control cohort and n=5 in the experimental cohort). A difference in IL-10 levels in the same patient population was not observed when we compared the first sample to the last sample (week 7 of etanercept and gemcitabine). All other cytokines did not show a significant change with etanercept and gemcitabine therapy at any time point. There was also no difference between the two treatment cohorts when comparing the various cytokines, regardless of tumor response.

For patients in the treatment group, we further categorized correlative findings according to CBR. IL-10 levels were higher in patients identified as responders as compared to the non-responders 28.04 vs. 26.85 (p=0.01), respectively (Table 4). The same limitations for interpretation apply as above. This difference in IL-10 level was not seen when we compared the first and second samples, nor the first and last samples drawn. Again, we did not observe any significant trend with the other cytokines.

Table 4.

Cytokine Levels (mean and standard deviation) by groups (CBR)

| Outcome | Responders (n=6) |

No Responders (n=7) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | mean (SD) |

28.04 (1.93) |

26.85 (1.38) |

0.01 |

| IL-1b | mean (SD) |

16.2 (7.29) |

13.07 (7.44) |

0.13 |

| NFkB | mean (SD) |

6.03 (4.62) |

4.38 (3.13) |

0.13 |

| IL-12 | mean (SD) |

35.66 (1.86) |

36.11 (1.24) |

0.28 |

| TNF | mean (SD) |

26.66 (3.84) |

27.26 (4.82) |

0.61 |

| IFN | mean (SD) |

28.7 (2.13) |

28.63 (1.55) |

0.88 |

| IL-6 | mean (SD) |

29.25 (1.31) |

29.29 (1.39) |

0.92 |

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer continues to be a devastating disease, with disappointing survival rates despite systemic therapy and morbidity with disproportionate amount of pain and cachexia. Currently, the standard of care is gemcitabine, with or without erlotinib, or the combination of 5-Fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) in patients with excellent performance status.16,20,21 At the time this study was designed, single-agent gemcitabine was the only standard for first-line therapy. The main goal as described above for combining the TNF inhibitor etanercept to gemcitabine was to enhance cytotoxicity and reverse cachexia.

The combination was safe and tolerable with the majority of Grade 3 and 4 adverse events due to hematological toxicities. However, the study did not reach its primary endpoint. The interpretation of the results of our study is limited by the relatively small patient sample and correlative samples. It is unlikely that etanercept had an adverse effect when added to gemcitabine, with the combination showing similar efficacy results when compared to the gemcitabine cohort and historical controls.16 CBR was the secondary endpoint to assess for cancer cachexia and pain in this study. However, additional measurements such as fatigue, muscle strength, muscle function, and CT or DEXA scans to measure lean muscle mass should be considered in future studies of cancer cachexia.

It is possible that the dose of etanercept at 25mg twice weekly, which is the dose approved for use in the treatment of psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis, needed to be escalated further to more effectively alter the proinflammatory cytokines, and elicit tumor response or CBR in pancreatic cancer patients.13,22 For example, the recommended dose for plaque psoriasis is 50 mg twice weekly for 3 months followed by 50 mg weekly.13 In fact, a phase IB trial of etanercept in recurrent ovarian cancer showed tolerability up to doses of 25mg thrice weekly, although this resulted in increased severity of skin rash, itching, and fatigue at the higher dose frequency.23

Two other studies have examined the role anti-TNF directed therapy in the treatment of pancreatic cancer and cachexia. One phase II study with thalidomide, an immunomodulator known to decrease TNF levels, demonstrated an improvement in weight and lean body mass at 8 weeks as compared to placebo.24 In contrast, a phase II study of gemcitabine and infliximab, a monoclonal antibody blocking TNF, did not show a benefit in preserving lean body mass or survival.25 Possible reasons for the lack of activity of TNF blockade with etanercept or infliximab may be that targeting TNF alone is not sufficient for anti-tumor response or reversal of cachexia. For example, although TNF activation of NF-kB is necessary in muscle breakdown, TNF by itself is not sufficient. In vitro, it has been demonstrated that the combination of IFN and TNF activate NF-kB and suppress mRNA production of MyoD, a myocyte regulator factor that is important for skeletal muscle differentiation and repair.26 IFN did not potentiate TNF activation of NF-kB, and therefore could have separate downstream effectors that lead to skeletal muscle loss. Thus specific anti-TNF therapy may not be sufficient to inhibit muscle breakdown. Additionally, serum TNF may not always be detectable in cachectic cancer patients, and TNF levels do not necessarily correlate with weight loss.27 Conversely, TNF delivery has been used as anti-cancer therapy to stimulate apoptosis of tumor-associated endothelial cells. However, systemic toxicities of TNF delivery have made it prohibitive, and thus strategies for direct delivery to the tumor site were developed. One example is TNFerade, which is a replication-deficient adenovector expressing human TNF under the control of a radiation-inducible promoter.28,29 The PACT trial, a phase II/III trial of TNFerade plus chemoradiation vs. chemoradiation alone in locally advanced pancreatic cancer, was discontinued due to inferior results of the experimental arm in the interim analysis.30

In our correlative analysis, IL-10 was the only cytokine shown to have statistically significant changes in both the two treatment cohort groups and in the groups identified as clinical benefit responders vs. non-responders. Although intriguing differences are observed, sample size was limited in each cohort to draw meaningful conclusions from our findings. Of note, IL-10 was shown to be elevated in pancreatic cancer patients, and its levels were recently shown to decrease with gemcitabine-based therapy.31,32 Although the significance of this finding is unknown, it is thought that IL-10 is immunosuppressive and its inhibition may restore immunity and improve the chances of response in pancreas cancer.30,33

In conclusion, the combination of etanercept and gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer was safe and tolerable but failed to show any significant enhancement of gemcitabine. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effect of gemcitabine-based therapy on IL-10 and its role in pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This study was funded by R21 CA101360 to M. Villalona-Calero and drug limited support from Immunex

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure: Tanios Bekaii-Saab, Amgen Consultant(C)

References

- 1. [Accesssed January 3, 2012]; http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html#incidence-mortality.

- 2.Kemik O, Kemik AS, Begenik H, et al. The relationship among acute-phase response proteins, cytokines, and hormones in various gastrointestinal cancer types patients with cachectic. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2012;31:117–125. doi: 10.1177/0960327111417271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martignoni ME, Kunze P, Hildebrandt W, et al. Role of Mononuclear Cells and Inflammatory Cytokines in Pancreatic Cancer-Related Cachexia. Clin Canc Res. 2005;11:5802–5808. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruan H, Hacohen N, Golub TR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha suppresses adipocyte-specific genes and activates expression of preadipocyte genes in 3T3-L1 adipocytes: nuclear factor-kappaB activation by TNF-alpha is obligatory. Diabetes. 2002;51:1319–1336. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plomgaard P, Fischer CP, Ibfelt T, et al. TNF-alpha modulates human in vivo lipolysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;96:543–549. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammerstedt A, Isakson P, Gustafson B, et al. Wnt-signaling is maintained and adipogenesis inhibited by TNFα but not MCP-1 and resistin. Biochemi Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Madrid LV, et al. NF-kappaB induced loss of MyoD messenger mRNA: Possible role in muscle decay and cachexia. Science. 2000;289:2363–2366. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, et al. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2004;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai D, Frantz JD, Tawa NE, et al. IKKβ/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell. 2004;119:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trauzold A, Wermann H, Arlt A, et al. CD95 and TRAIL receptor-mediated activation of protein kinase C and NF-kappaB sensitizes human pancreatic carcinoma cells to apoptosis induced by etoposide (VP16) or doxorubicin. Oncogene. 2001;20:4258–4269. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egberts JH, Cloosters V, Noack A, et al. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy Inhibits Pancreatic Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1443–1450. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:763–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT, et al. Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2014–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis JC, Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3230–3236. doi: 10.1002/art.11325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:924–930. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in Survival and Clinical Benefit With Gemcitabine as First-Line Therapy for Patients With Advanced Pancreas Cancer: A Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh CB, Lowe MP, Rovin BH, et al. Lymphocytes produce IL-1beta in response to Fcgamma receptor cross-linking: effects on parenchymal cell IL-8 release. J Immunol. 1998;160(8):3942–3948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Tuner SC, et al. Human natural killer cells: A unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56(bright) subset. Blood. 2001;97:3146–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehniger TA, Shah MH, Turner MJ, et al. Differential cytokine and chemokine gene expression by human NK cells following activation with IL-18 or IL-15 in combination with IL-12: implications for the innate immune response. J Immunol. 1999;162:4511–4520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRNOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:478–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madhusudan S, Muthuramalingam SR, Braybooke JP, et al. Study of Etanercept, a Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Inhibitor, in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5950–5959. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon JN, Trebble TM, Ellis RD, et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of cancer cachexia: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2005;54:540–545. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widenmann B, Malfertheiner P, Freiss H, et al. A Multicenter, Phase II Study of Infliximab Plus Gemcitabine in Pancreatic Cancer Cachexia. J Support Oncol. 2008;6:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladner KJ, Caligiuri MA, Guttridge DC. Tumor necrosis factor-regulated biphasic activation of NF-kappa B is required for cytokine-induced loss of skeletal muscle gene products. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2294–2303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falconer JS, Fearon KC, Plester CE, et al. Cytokines, the acute-phase response, and resting energy expenditure in cachectic patients with pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;219:325–331. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199404000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mauceri HJ, Hanna NN, Wayne JD, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) gene therapy targeted by ionizing radiation selectively damages tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4311–4314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallahan DE, Mauceri HJ, Seung LP, et al. Spatial and temporal control of gene therapy using ionizing radiation. Nat Med. 1995;8:786–791. doi: 10.1038/nm0895-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [Accessed March 30, 2012];FierceBiotech (March 29, 2010) GenVed Discontinues Phase 3 Clinical Trial of TNFerade. http://www.fiercebiotech.com/press-releases/genvec-discontinues-phase-3-clinical-trial-tnferade.

- 31.Bellone G, Turletti A, Artusio E, et al. Tumor-Associated Transforming Growth Factor-B and Interleukin-10 Contribute to a Systemic Th2 Immune Phenotype in Pancreatic Carcinoma Patients. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65149-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bang S, Kim H-S, Choo YS, et al. Differences in Immune Cells Engaged in Cell-Mediated Immunity After Chemotherapy for Far Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas. 2006;32:29–36. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000191651.32420.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Bernstroff W, Voss M, Freichel S, et al. Systemic and Local Immunosuppression in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:925s–932s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]