Abstract

Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen is a rare but potentially lethal condition. It can remain asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic for a long time. An 81-year-old woman presented with an extremely enlarged spleen. She suffered from progressive anemia and required a red blood cell transfusion once a month. Although computed tomography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging were performed for diagnosis, a confirmed diagnosis was not obtained. Her enlarged spleen compressed her stomach, and she suffered from gastritis and a sense of gastric fullness just after meals. She underwent laparoscopic splenectomy for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. Her post-operative course was uneventful. After surgery, her red blood cell and platelet counts increased markedly. The tumor was diagnosed as splenic histiocytic sarcoma. Post-surgical chemotherapy was not performed, and the patient died of liver failure due to liver metastasis 5 mo after surgery. Laparoscopic splenectomy is minimally invasive and useful for the relief of symptoms related to hematological disorders. However, in cases of an enlarged spleen, optimal views and working space are limited. In such cases, splenic artery ligation can markedly reduce the size of the spleen, thus facilitating the procedure. The case reported herein suggests that laparoscopic splenectomy may be useful for the treatment of splenic malignancy.

Keywords: Histiocytic sarcoma, Laparoscopic splenectomy, Malignancy, Splenomegaly, Chemotherapy

Core tip: Surgeons usually avoid choosing laparoscopic surgery for splenic malignancy because an enlarged spleen disrupts optimal views. Some authors reported that initial ligation of the splenic artery led to shrinkage of the spleen; therefore, the operation was easier. We report a case of splenic malignancy that was diagnosed as histiocytic sarcoma and treated by laparoscopic splenectomy with initial ligation of the splenic artery. In this case, because the size of the spleen was reduced after splenic artery ligation, the laparoscopic operation was performed safely. The patient was discharged 12 d after the operation despite her old age.

INTRODUCTION

Histiocytic sarcoma is a rare, malignant neoplasm that occurs in the lymph nodes, skin, and gastrointestinal tract and that can be defined as a malignant proliferation of cells. In this condition, the affected cells demonstrate morphological and immunophenotypical features similar to those of mature tissue histiocytes[1]. Histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen is an extremely rare and potentially lethal condition that can remain asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic for a long time. However, its clinicopathological features have not been well characterized[1-3]. Early evaluation and diagnosis before dissemination may improve the prognosis of this disease, but diagnostic imaging has not been sufficiently efficacious. Therefore, early detection remains difficult. If the lesion is confirmed to be confined within the spleen, splenectomy may induce temporary remission of the disease.

Herein, we report a case of splenic histiocytic sarcoma treated by laparoscopic splenectomy. The patient’s clinical symptoms were undetectable for approximately 3 mo, but systemic recurrence occurred with a fatal outcome.

CASE REPORT

An 81-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and unstable angina pectoris visited her primary care physician for a periodic examination. She was diagnosed with anemia, which persisted for 1 year, and she was referred to a hematologist, who recommended a full examination. She was diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The patient’s anemia progressed gradually, and 2 units of red cell concentrate were administered per week. She was admitted to our hospital, and splenomegaly (> 10 cm in longitudinal diameter) was detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

On physical examination, the lower end of her spleen was palpable 7 cm below the left costal margin, but no superficial lymphadenopathy was observed. A complete blood count indicated anemia and thrombocytopenia, but her leukocyte count was within the normal range (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| AST (IU/L) | 11 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 6 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 141 |

| LAP (IU/L) | 25 |

| γ-GTP (mg/dL) | 10 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 1.8 |

| D-Bil (mg/dL) | 0.7 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 2.3 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28.3 |

| Cre (mg/dL) | 0.8 |

| PT (%) | 93.2 |

| AMY (IU/L) | 42 |

| HCV-Ab | (-) |

| HBs-Ag | (-) |

| WBC/mm3 | 6350 |

| RBC/mm3 | 291000 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.2 |

| Ht (%) | 27.6 |

| Plt/mm3 | 13000 |

Marked anemia and thrombocytopenia are shown. A dominant elevation in direct bilirubin was observed. AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; LAP: Leucine aminopeptidase; γ-GTP: γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; T-Bil: Total bilirubin; D-Bil: Direct bilirubin; Alb: Albumin; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; Cre: Creatinine; PT: Prothrombin time; AMY: Amilaza; HCV-Ab: Hepatitis C virus-antibody; HBs-Ag: Hepatitis B surface antigen; WBC: White blood cell; RBC: Red blood cell; Hb: Haemoglobin; Ht: Haematocrit; Plt: Platelets.

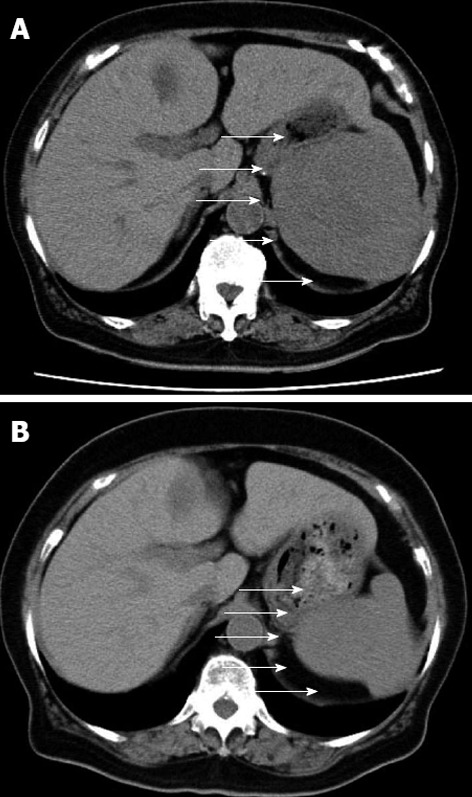

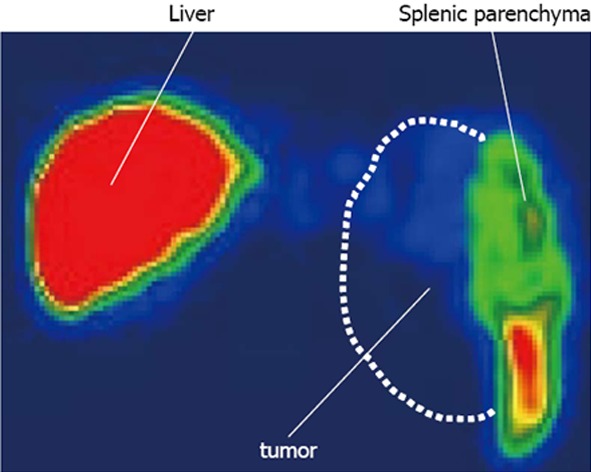

An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed splenomegaly (9.5 cm in longitudinal diameter; Figure 1A). One year previously, she showed mild splenomegaly (6 cm in longitudinal diameter; Figure 1B). Technetium-99 m colloid scintigraphy revealed a partial defect in her spleen (Figure 2). Because there were no defect lesions in the liver on this scintigram, we diagnosed no liver metastasis.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography. A: Just before the operation; B: 1 year before the operation. Arrows show the splenic tumor.

Figure 2.

Technetium-99 m colloid scintiscanning. The broken line shows the splenic tumor. The tumor did not uptake technetium-99 m colloid, and the tumor was therefore shown as a defect.

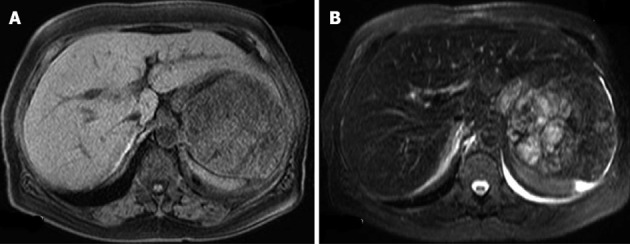

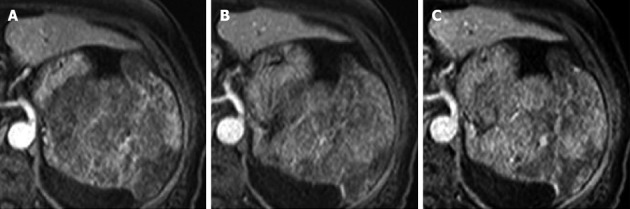

An abdominal dynamic MRI showed a multilobular splenic tumor, which appeared as an iso-intense solid mass on T1-weighted imaging (Figure 3A) and a high-intensity multi-lobular mass (10.5 cm in diameter) on T2-weighted imaging (Figure 3B). The tumor was enhanced on dynamic MRI from 20 to 120 s after the injection of contrast medium (Figure 4). Based on these findings, the differential diagnoses were malignant lymphoma, metastatic splenic tumor (origin unknown), hemangioma, and hemangiosarcoma, but we could not arrive at a definite diagnosis. Distant metastatic lesions, which are proof of a malignant tumor, were not detected by any imaging modality. Because the patient’s anemia and thrombocytopenia worsened gradually, red blood cell and platelet transfusions were performed once or twice per week. After admission, gastritis and a sense of gastric fullness, which is a symptom of compression by an enlarged spleen, worsened. We decided to perform splenectomy as an excision biopsy. Laparoscopic splenectomy was selected as the operation procedure.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging just before the operation. A: An iso-intense solid mass on T1-weighted images; B: A high-intensity multi-lobular mass on T2-weighted images.

Figure 4.

Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. The tumor was enhanced from 20 to 120 s after the injection of contrast medium. Contrast medium gradually pooled in the tumor. A: 20 s; B: 60 s; C: 120 s.

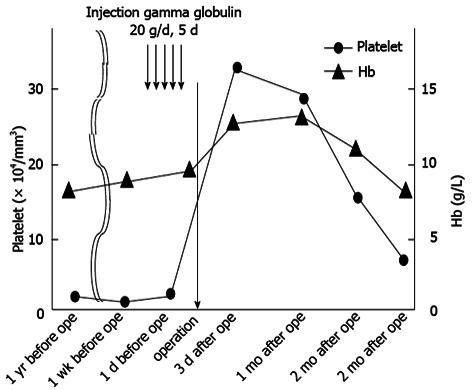

To prevent the progression of anemia and thrombocytopenia, high-dose gamma globulin was infused (20 g/d for 5 d), but the red blood cell and platelet counts did not increase (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Clinical course of the patient. Transition of the platelet number and hemoglobin value from 1 year before the operation to 3 mo after the operation. The black arrow shows the operation time. The circle shows the platelet number. The triangle shows the hemoglobin value.

A 12-mm trocar was inserted by the open method at the mid-clavicular line parallel to the umbilicus, and 3 12-mm trocars were inserted around the spleen during the procedure. A laparoscopic view showed that the liver was normal. In addition, no metastatic or disseminated lesions were detected. The spleen occupied nearly the entire left upper and side cavity of the abdomen. After the splenic artery was ligated, the size of the spleen was markedly reduced. The spleen was placed in a polyethylene bag and extracted from the incision through the first port, which was extended to 7 cm. The operation time was 3 h and 58 min, and the blood loss was 236 g.

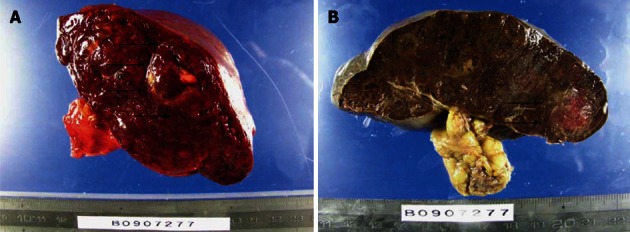

The weight of the resected spleen was 720 g, and it measured 21 cm × 12 cm × 5 cm. Macroscopically, the spleen showed multiple nodules with different colors from normal splenic tissue (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Macroscopic findings of the spleen. A: The raw specimen. Multiple nodules with different colors from normal splenic tissue; B: The specimen after formalin fixation. The arrows show the tumor.

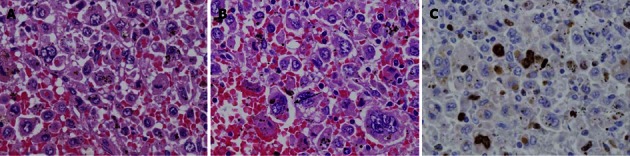

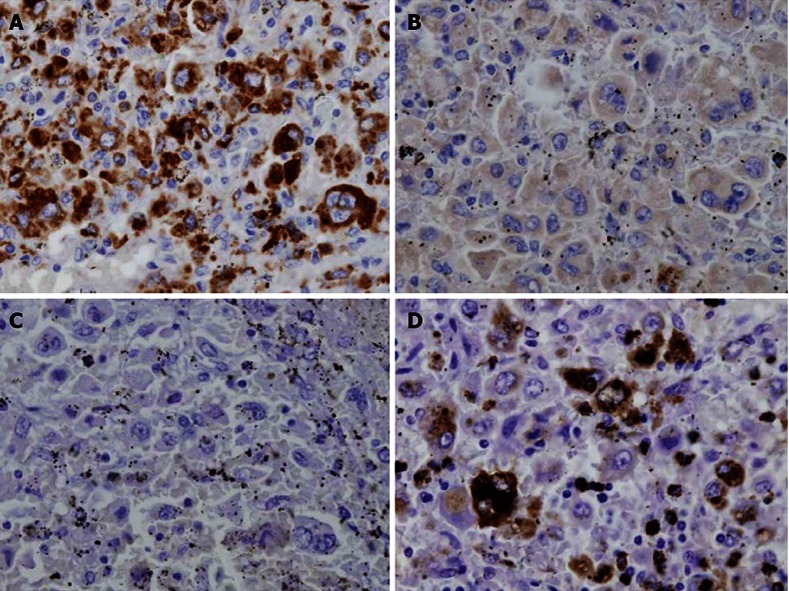

The microscopic findings were the following. The tumor consisted of cells with a foamy cytoplasm, hemosiderin-containing phagocytic cells, and multilobular megakaryocytes. The MIB-1 labeling index was 8.1% (Figure 7). Immunohistopathological staining was positive for CD68 and lysozyme, partially positive for p53, and negative for CD1a, CD4 and S-100 protein; therefore, the tumor cells were diagnosed as being of histiocyte origin (Figure 8). From these findings, the tumor was diagnosed as histiocytic sarcoma.

Figure 7.

Microscopic findings. A: Giemsa stain. Magnification is × 200; B: Giemsa stain. Magnification is × 400; C: MIB-1 labeling stain. The tumor consisted of cells with a foamy cytoplasm, hemosiderin-containing phagocytic cells (white arrow), and multilobular megakaryocytes. The MIB-1 labeling index was 8.1%.

Figure 8.

Immunohistopathological staining. A: CD68; B: CD1a; C: S-100 protein; D: lysozyme CD68 stained positive. CD1a and S-100 protein were negative. Lysozyme was partially positive.

The anemia and thrombocytopenia were improved only 3 d after the operation (Figure 5). The post-operative course was uneventful, and she was discharged 12 d after surgery.

The platelet count decreased gradually 2 mo after surgery, and multiple liver metastases were revealed on magnetic resonance imaging 3 mo after the operation. Her liver functions rapidly deteriorated, and chemotherapy could not be performed. The patient died of liver failure 5 mo after surgery.

DISCUSSION

According to the recent World Health Organization classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, histiocytic sarcoma is a malignant proliferation of cells showing morphologic and immunophenotypic features similar to those of mature tissue histiocytes. Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen is a rare condition, and its clinico-pathological features have not been well described[4]. Clinically, it is generally accepted that most patients with histiocytic sarcoma show a limited response to chemotherapy and a high mortality rate[5]. Recently, some reports have shown that early diagnosis before dissemination of this disease may improve the prognosis[3]. Hornick et al[6] reported that tumor size may be a prognostic factor. Vos et al[7] showed that all patients with poor survival in their report had tumors over 3.5 cm in longitudinal diameter. The tumor size may be a strong factor for determining the stage of the disease. In our case, disseminated lesions were not recognized before the operation, but the size of the tumor of the spleen was over 10 cm in longitudinal diameter. Therefore, our patient was considered to be in an advanced stage. Our patient also recurred only 3 mo after the operation and died of the disease 5 mo after surgery.

In our case, we could not confirm the diagnosis preoperatively. Specific hematological markers do not exist for this disease. Recently, Vos et al[7] reported CD163, a hemoglobin scavenger receptor, as a new macrophage- related differentiation marker, which is more specific than the conventional histiocyte-related molecules, such as CD68 and lysozyme. However, only histopathological examination can reveal the existence of the disease. Moreover, our patient suffered from abdominal fullness and progressive anemia and thrombocytopenia. These symptoms were thought to be caused by splenomegaly and hypersplenism. Therefore, we decided to perform a splenectomy for both therapy and diagnosis.

Splenic malignancy may be accompanied by severe hematologic disease or a metastatic lesion in many cases. If splenectomy is performed in these cases, additional therapy should be administered as soon as possible after surgery. Laparoscopic splenectomy is less invasive than open splenectomy[8] and more quickly can lead to additional therapy. Some reports have demonstrated not only the feasibility of laparoscopic splenectomy but also its significant benefits over open splenectomy for the treatment of benign hematologic conditions[9-11]. Additionally, in our case of malignancy, anemia and thrombocytopenia were improved, and chemotherapy could be performed.

An enlarged spleen disrupts the optimal operative view. Although hand-assisted laparoscopic[12] splenectomy for a solitary splenic tumor has been reported, the inserted hand also disturbs the optimal view in massive splenomegaly. In our case, we ligated the splenic artery first, expecting a volume reduction of the spleen. In case that the main cause of massive splenomegaly is a space-occupying lesion in the spleen, the spleen size after ligation of the splenic artery may not be equivalent to that of a spleen without space-occupying lesions. However, Trelles et al[13] reported that the initial ligation of the splenic artery leads to volume reduction of the spleen in cases of massive splenomegaly. Additionally, in our case, initial splenic artery ligation was effective for inducing a splenic volume reduction.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Venskutonis D, Stoot JHMB S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

References

- 1.Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Banks P, Campo E, Chan JK, Favera RD, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, et al. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology. 2002;41:1–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audouin J, Vercelli-Retta J, Le Tourneau A, Adida C, Camilleri-Broët S, Molina T, Diebold J. Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen associated with erythrophagocytic histiocytosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:107–112. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi S, Kimura F, Hama Y, Ogura K, Torikai H, Kobayashi A, Ikeda T, Sato K, Aida S, Kosuda S, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen: case report of asymptomatic onset of thrombocytopenia and complex imaging features. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:83–87. doi: 10.1007/s12185-007-0008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. World Health Organization classification of tumours pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001. pp. 273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copie-Bergman C, Wotherspoon AC, Norton AJ, Diss TC, Isaacson PG. True histiocytic lymphoma: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1386–1392. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CD. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1133–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vos JA, Abbondanzo SL, Barekman CL, Andriko JW, Miettinen M, Aguilera NS. Histiocytic sarcoma: a study of five cases including the histiocyte marker CD163. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:693–704. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telem D, Chin EH, Colon M, Nguyen SQ, Weber K, Divino CM. Minimally invasive surgery for splenic malignancies. Minerva Chir. 2008;63:529–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman RS, Yahanda AM, Mansfield PF, Hemmila MR, Sweeney JF, Porter GA, Kumparatana M, Leroux B, Pollock RE, Feig BW. Laparoscopic splenectomy in patients with hematologic malignancies. Am J Surg. 1999;178:530–536. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman RL, Hiatt JR, Korman JL, Facklis K, Cymerman J, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic or open splenectomy for hematologic disease: which approach is superior? J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flowers JL, Lefor AT, Steers J, Heyman M, Graham SM, Imbembo AL. Laparoscopic splenectomy in patients with hematologic diseases. Ann Surg. 1996;224:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yano H, Nakano Y, Tono T, Ohnishi T, Iwazawa T, Kimura Y, Kanoh T, Monden T. Hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy for splenic tumors. Dig Surg. 2004;21:215–222. doi: 10.1159/000079395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trelles N, Gagner M, Pomp A, Parikh M. Laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly: technical aspects of initial ligation of splenic artery and extraction without hand-assisted technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:391–395. doi: 10.1089/lap.2007.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]