Abstract

Objective

To identify and define the imaging characteristics of children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD).

Design

Retrospective medical records review and analysis of both temporal bone computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance images (MRI) in from children with the diagnosis of ANSD.

Setting

Tertiary referral center.

Patients

118 children with the electrophysiological characteristics of ANSD with available imaging studies for review.

Interventions

Two neuroradiologists and a neurotologist reviewed each study and consensus descriptions were established.

Main outcome measures

The type and number of imaging findings were tabulated.

Results

Sixty-eight (64%) MRIs revealed at least one imaging abnormality while selective use of CT identified 23 (55%) with anomalies. The most prevalent MRI findings included cochlear nerve deficiency (n=51; 28% of 183 nerves), brain abnormalities (n=42; 40% of 106 brains) and prominent temporal horns (n=33, 16% of 212 temporal lobes). The most prevalent CT finding from selective use of CT was cochlear dysplasia (n=13; 31%).

Conclusions

MRI will identify many abnormalities in children with ANSD that are not readily discernable on CT. Specifically, both developmental and acquired abnormalities of the brain, posterior cranial fossa, and cochlear nerves are not uncommonly seen in this patient population. Inner ear anomalies are well delineated using either imaging modality. Since many of the central nervous system findings identified in this study using MRI can alter the treatment and prognosis for these children, we believe that MRI should be the initial imaging study of choice for children with ANSD.

Keywords: auditory neuropathy, auditory dys-synchrony, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, imaging

Introduction

Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder (ANSD) is a clinical syndrome in which a significant discrepancy exists between measures of cochlear function and other, more central locations within the auditory system. Specifically, patients exhibit normal measures of outer hair cell function, as evidenced by the presence of either otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) and/or a cochlear microphonic (CM) in the setting of disordered/aberrant auditory signal conduction in more proximal sites within the auditory processing stream (1-4). A detailed description of the epidemiology, perceptual consequences, and potential mechanisms of ANSD has been reviewed previously (5). The prevalence of ANSD has been reported between 0.5% and 40% depending on the population studied (3,6-8). The etiology of ANSD appears to be multifactorial and likely results from a variety of lesions throughout the auditory pathway, from inner hair cells (IHCs) to the cerebral cortex. Lesions of the IHCs, the synapse between IHCs and type I afferents of the auditory division of the eighth cranial nerve, the auditory nerve proper (ganglionopathy, demyelination, or axonopathy), the synapse between the type I afferent axons and cochlear nucleus target cells, the cochlear nucleus itself, and central projections are possible and have been specifically postulated including conditions of mixed lesions (4,9-11). These lesions can be congenital or acquired and can be part of a known clinical syndrome such as Mohr-Tranebjaerg syndrome or seen in isolation. Specific genes have also been mapped in both syndromic (12) and non-syndromic cases (13). A systemic neuropathic process may affect the auditory nerve and account for the clinical findings (14). Cochlear nerve deficiency (CND) describes an anatomically small or absent auditory nerve and represents a severe and literal form of ANSD (15). With the breadth of possible pathophysiologic mechanisms, ANSD can manifest with a wide variety and degree of symptoms and findings (16). Conversely, this wide variety of lesions may exhibit indistinguishable audiometric and electrophysiologic results (11).

Evaluation of children with hearing loss requires a multidisciplinary effort that includes audiological assessment, selective use of laboratory testing, referrals among a variety of pediatric specialists, and selective use of radiological imaging studies. In our program, imaging is recommended immediately after electrophysiological measurements have established the diagnosis of ANSD (15). Some controversy currently exists regarding which imaging modality is the most appropriate for the assessment of children with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) (15,17-23). It is clear that both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are able to sufficiently define the architecture of the otic capsule. While CT is superior for assessing intratemporal facial nerve location, inner ear ossification, and temporal bone pathology, recent studies have demonstrated that MRI provides superior definition of the soft tissues of the auditory system proximal to the inner ear including the cochlear nerve and brain (15,19,21,22,24). Moreover, MRI can better assess post-meningitic fibrosis of the labyrinth that has not yet undergone ossification (21).

One shortcoming of MRI is in the assessment of cochlear nerve integrity in the setting of a narrow (<3mm in diameter) or small internal auditory canal (IAC) (17). In such cases, the lack of neural separation within the small IAC makes MRI resolution insufficient for seeing the cochlear nerve and its’ course. In such cases, CT can at least identify a subset of cases where the bony cochlear nerve canal (BCNC) is not patent, thereby making the diagnosis of CND highly likely. Nonetheless, in some cases where the IAC is small, the BCNC is remains patent and the cochlear nerve status is ultimately indeterminate (17).

Since 2003, we have been using MRI as the initial imaging evaluation for most children with SNHL including those with ANSD. CT is used selectively following MRI to identify: (1) malposition of the facial nerve in cases with semicircular canal dysplasia, (2) ossification of the inner ear when labyrinthine obstruction is evident, (3) the extent of temporal bone pathology when present and (4) the patency of the BCNC in the setting of a narrow IAC (<3mm). The purpose of the current study was to report the patient characteristics and imaging findings of a population of children with ANSD. Since ANSD is an auditory disorder with a relatively high prevalence of neurological pathology, we hypothesized that cochlear nerve and central nervous system anomalies would be relatively common in this cohort of patients. To the best of our knowledge, this report marks the first attempt to systematically describe and classify the imaging findings from children with ANSD.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

At the present time, more than 1000 hearing-impaired children are being managed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). Retrospective review of the databases from the Division of Audiology at UNC Hospitals (UNCH) and the W. Paul Biggers Carolina Children’s Communication Disorders Program (CCCDP) in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at UNC was undertaken to identify those children with ANSD. Inclusion criteria included 1) a diagnosis of ANSD, and 2) available MRI and/or CT imaging for analysis within the UNCH system. The diagnosis of ANSD was established by the presence of OAEs and/or a CM in conjunction with an aberrant or absent neural responses on ABR. The diagnostic protocol has been described in detail previously (15,25). Approval of this study was obtained from Biomedical Institutional Review Board (IRB) at UNC.

Demographic and medical data were gathered from the electronic medical record. Demographic data included age, gender, and race. Medical information sought included a history of: prematurity, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, cerebral palsy, other neuropathies, ototoxic medication exposure, intraventricular hemorrhage, familial ANSD, perinatal infection, hyperbilirubinemia, kernicterus, seizure disorder, or cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.

Imaging

The MRI techniques used at UNC have been described in detail previously (15,17,18). MRI evaluations were performed using our institution’s dedicated 8th cranial nerve protocol, performed on either a 1.5-T scanner (Sonata, Avanto, Vision, or Symphony; Siemens Medical Solutions, Inc., Malvern, PA, U.S.A.) or a 3-T scanner (Trio, Siemens Medical Solutions, Inc., Malvern, PA, U.S.A.), using a multichannel head coil. The protocol includes sagittal unenhanced T1-weighted images and axial fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T2-weighted images through the brain, as well as high-resolution 3D constructive interference in the steady state (CISS) or fast recovery fast spin-echo (RESTORE) images through the temporal bones. Parameters for the CISS sequence varied by scanner (repetition time [TR], 5.42-12.25 ms; echo time [TE], 2.42-5.9 ms; flip angle [FA], 50-80°; field of view [FOV], 120-180 mm; matrix size, 256; number of averages [NEX], 1-2), with resultant voxel sizes ranging from 0.5×0.5×0.5 mm to 0.7×0.7×0.7 mm. The RESTORE sequence, which was performed only on the Sonata, was acquired with the following parameters: TR, 1000 ms; TE, 136 ms; FA, 180°; FOV, 140 mm; matrix size, 192; NEX, 1) resulting in a voxel size of 0.7×0.7×0.7 mm. Total scan time for each study was approximately 20 minutes. The temporal bone sequences were reconstructed in the axial plane as well as in an oblique sagittal plane oriented perpendicular to the long axis of each IAC for viewing.

Temporal bone CT scans were performed on either a 16- or 64-slice CT scanner (Sensation 16 or Sensation 64, Siemens Medical Solutions, Inc., Malvern, PA, U.S.A.). Contiguous direct sequential axial and coronal images (120 kVp, 200 mAs) were acquired through the temporal bones using a collimation of 0.6 mm or 0.75 mm.

All MRI and CT images were reviewed on a clinical PACS system (IMPAX 5.0; AGFA, Ridgefield Park, NJ, U.S.A) by two neuroradiologists (B.Y.H. and M.C.) and a neurotologist (C.A.B.). All quantitative measurements were made using the standard ruler tool included in our PACS software package. For both MRI and CT examinations, the reviewers subjectively examined the temporal bones for the presence of cochlear, vestibular, or semicircular canal abnormalities as well as for enlargement of the endolymphatic duct and sac. The various inner ear malformations have been described previously (26). The diameter of each internal auditory canal (IAC) at the level of porus acousticus was measured from the posterior margin of the porus acousticus to the anterior wall of the IAC along a line perpendicular to the long axis of the IAC on the axial temporal bone image giving the largest measurement. A small IAC is defined as less than 3 mm on cross-sectional diameter (27,28). For CT imaging, a small cochlear nerve aperture or bony cochlear nerve canal (BCNC) was defined as 1.3 mm or less in size (17).

On the MRI studies, each IAC was evaluated for the presence and size of the cochlear nerve. The nerves were categorized as (1) normal; (2) small; (3) suspected small; (4) suspected absent; (5) absent, (6) unknown. The differentiation between normal and small cochlear nerves was determined subjectively based on the nerve’s size relative to the adjacent facial or vestibular nerves within the IAC on the oblique sagittal images. After Glastonbury et al. (29), we designated the nerve absent when it could not be identified on axial, coronal, or reconstructed coronal oblique IAC images. An extremely small nerve below the limits of resolution of MRI would appear absent in this context. The nerve is considered small when the nerve is evident but substantially smaller than the other nerves in the IAC or smaller than the cochlear nerve in the contralateral ear. The terms aplasia, hypoplasia, agenesis, or degeneration are avoided so as to not imply a mechanism or causality, because this remains speculative.

Intracranial MRI images were also reviewed for concomitant brain abnormalities, which were subjectively described. Intracranial abnormalities were categorized into 7 anatomical subgroups: temporal horn abnormalities, white matter abnormalities, myelination abnormities, CSF and/or ventricular abnormalities, brainstem/cerebellum abnormalities, midbrain/cerebrum abnormalities and other various malformations/abnormalities.

Data and Analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet (Redmond, Washington, USA). Descriptive statistical analysis included means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequency calculations for the categorical variables to help summarize the characteristics of the subjects. For categorical data, differences were sought using the Fisher Exact test. Significance thresholds were set to 0.05.

Results

Demographics

One hundred eighteen (80%) of the 147 children with ANSD met criteria for inclusion in the study. The remaining children were without available imaging for review and were excluded from further investigation. All children (100%) had evidence of a CM with absent neural responses on auditory brainstem response testing. OAE results are actually quite variable for the group because of issues in timing of the measurements, frequency, and middle ear status among others (3,30,31). Twenty-eight (24%) of 118 carried the diagnosis of ANSD in one ear while 90 (76%) children were bilaterally affected. Thus, 208 ears with ANSD in 118 children were available for study. Children included in the study were imaged between November of 1996 and September of 2008. There were 69 (58%) males and 49 (42%) females. Sixty-nine (58%) children were Caucasian, 29 (25%) were African-American, and 20 (17%) were from other racial populations. Thirty-one (26%) children had both MRI and CT imaging data available for analysis, 76 (64%) had exclusively MRI data and 11 (9%) underwent CT alone. The mean age at MRI was 2.34 ± 2.37 years and the mean age at CT as 2.47 ± 2.35 years.

Medical History

A summary of the significant medical histories of our population can be found in Table 1. Thirty (25%) children had no identifiable significant medical history other than a diagnosis of ANSD. Prematurity was the most common historical finding (n=50, 42%) followed by NICU admission during the postnatal period (n= 45, 38%), history of mechanical ventilation (n= 32, 27%) and hyperbilirubinemia (n=24, 20%). Other neuropathies were found in 4 (3%) children and included peripheral neuropathy not otherwise specified, peripheral neuropathy with optic neuropathy, progressive encephalopathy, and left- sided congenital facial paralysis. Children with bilateral ANSD were more likely to have other medical conditions (81% bilateral vs. 54% unilateral; p=0.0058). Forty-three (36%) children have received a cochlear implants in either one (98%) or both ears (n=1; 2%). The mean age at the time of cochlear implantation was 48.4 ±35.9 months and the mean pure tone average (PTA) at the time of implantation was 92.8±16 dB HL.

Table 1.

Significant medical history of a population of children with ANSD1 (n = 118)

| Abnormality | Unilateral ANSD No. (%)a | Bilateral ANSD No. (%)a | Total No. (%)b | Probability2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only ANSD1 | 13 (43) | 17 (57) | 30 (25) | |

| Any medical history | 15 (17) | 73 (83) | 88 (75) | 0.006 |

| Specific historical diagnosis)c | ||||

| Prematurity | 6 (12) | 44 (88) | 50 (42) | 0.015 |

| NICU3 admission | 7 (16) | 38 (84) | 45 (38) | 0.122 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2 (6) | 30 (94) | 32 (27) | 0.007 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 4 (17) | 20 (83) | 24 (20) | 0.432 |

| Ototoxic medication exposure | 2 (12) | 14 (88) | 16 (14) | 0.352 |

| Family history of ANSD1 | 1 (11) | 8 (89) | 9 (8) | 0.684 |

| Seizure disorder | 1 (11) | 8 (89) | 9 (8) | 0.684 |

| Cerebral palsy | 3 (33) | 6 (67) | 9 (8) | 0.441 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 7 (6) | 0.196 |

| Other neuropathic condition | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 4 (3) | 0.238 |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (2) | 0.420 |

| Kernicterus | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| Perinatal infection | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| Other conditions | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 5 (4) | 0.591 |

Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder.

Fisher Exact Test.

Neonatal intensive care unit.

Percent of total number of children with a pertinent historical finding.

Percent of total number of children with ANSD.

Both the presence and absence of each condition was considered; only the number of positive findings for each condition is presented.

Imaging Findings

Sixty-eight (64%) of 107 MRIs revealed at least one imaging abnormality while 44 (41%) demonstrated 2 or more abnormalities. The ratio of MRIs with multiple versus isolated abnormalities was 1.83:1 (44:24). Selective use of CT identified 23 (55%) of 42 with at least one abnormality and 19 (45%) with 2 or more abnormalities. The ratio of CTs with multiple versus isolated abnormalities was 4.75:1 (19:4).

One hundred six of 107 MRIs studies were suitable for evaluation of labyrinthine architecture and revealed 11 (10%) cochlear, 7 (7%) vestibule and 6 (6%) semicircular canal malformations. Of the 42 CTs, 13 (31%) revealed a cochlear malformation, 5 (12%) had isolated vestibule anomalies, and 2 (5%) had semicircular canal dysplasia. In general, most malformations were bilateral and symmetrical and for patients with both MRI and CT available, all of the malformations were evident on both studies.

Fifty-one (28%) of 183 ears with ANSD with available and suitable MRI images demonstrated evidence of either definite or possible CND (Figure 1A-D, Table 2). There were 21 unilateral and 15 bilateral cases. Of the patient with available CT images, 15 (18%) ears had a small BCNC (<1.3 mm) while 9 (11%) had a completely closed or absent BCNC.

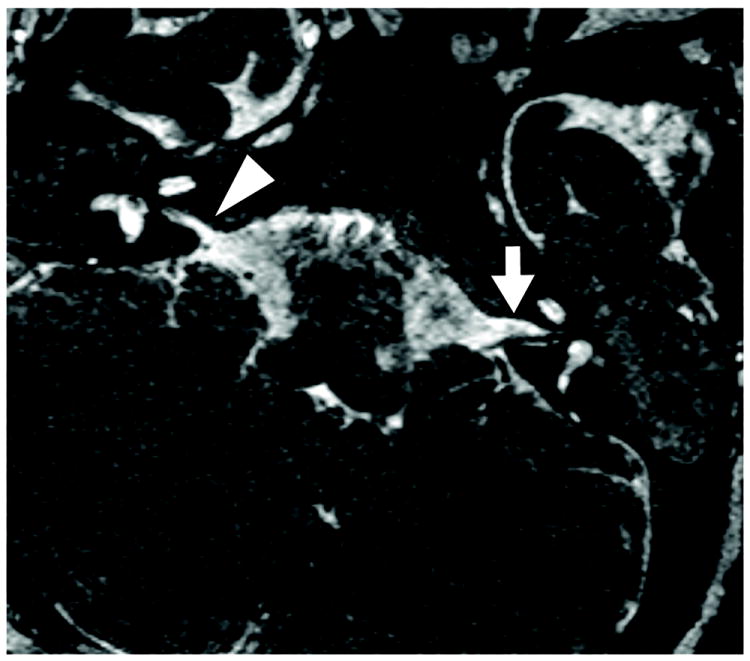

Figure 1.

A child with right-sided auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) evaluated with MRI using 3D constructive interference in the steady state (CISS) sequence of the bilateral internal auditory canals (IAC). Axial plane images demonstrate normal right (A) and left (B) IAC morphology. The oblique-sagittal reconstructed plane demonstrates normal facial (black arrow head) and cochlear (white arrow) nerves on the left (C). The oblique-sagittal image through the right IAC (D) demonstrates a normal facial nerve (arrowhead) and absent cochlear (white arrow) nerve. In both C & D, the vestibular nerves are normal.

Table 2.

Evaluation of cochlear nerves via MRI in children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD)

| Nerve status | No. of Cochlear Nerves (n=1831) |

|---|---|

| Normal | 132 |

| Small | 5 |

| Suspected small | 6 |

| Absent | 34 |

| Suspected absent | 3 |

| Undefined abnormality | 3 |

|

| |

| Total abnormal nerves2 | 51 |

Analysis of ears with ANSD and MRI images for evaluation.

Includes small, suspected small, absent, suspected absent and undefined abnormalities.

A relationship between the measured IAC (Figure 2) and cochlear nerve status as revealed on MRI among ears with ANSD was sought. As in previous studies, a normal IAC was defined as having a diameter of ≥3mm (17). Forty-nine (27%) of 183 IACs had a diameter <3mm and 134 (73%) met the definition as normal. Twenty (15%) ears with a normal IAC had CND while 31 (63%) ears with a small IAC had CND. Small IAC size on MRI was significantly associated with the presence of CND (p< 0.0001). A small BCNC on CT was also significantly associated with CND on MRI (p< 0.0001). All 19 (100%) ears with a small or closed BCNC had evidence of CND on MRI. Nonetheless, a normal size BCNC on CT did not rule out the possibility of CND on MRI as 4 of 33 (12%) ears had such findings.

Figure 2.

A child with bilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) evaluated with 3D constructive interference in the steady state (CISS) MRI. This image demonstrates a normal left IAC (3.1mm; white arrow) and a stenotic right IAC (1.4mm; white arrowhead).

Selective examination of the cerebellopontine angle (CP) cistern portion of cranial nerves 7 and 8 on MRI for the 36 children with evidence of CND (n= 51 ears) revealed 6 (12%) ears with no identifiable nerves, 15 (29%) ears with only 1 identifiable nerve and 30 (59%) ears with 2 identifiable nerves. Thirteen (87%) of the 15 ears with only 1 identifiable CP cistern nerve had an absent cochlear nerve in the IAC; the remaining 2 (13%) ears demonstrated significant abnormalities (Undefined grouping, Table 2). One child with a single CP cistern nerve had congenital facial paralysis along with CND. The remaining 14 children demonstrated normal facial nerve function. Nineteen (63%) of the 30 ears with 2 identifiable CP cistern nerves had absent cochlear nerves with another 9 (30%) ears demonstrating small or suspected absent cochlear nerves.

Examination of the MRI images for a variety of intracranial abnormalities revealed a number of findings, which are summarized in Table 3. One hundred six of 107 brains were suitable for analysis. The most common abnormalities included prominent temporal horns (n=33, 16% of 212 temporal lobes), CSF (figure 3) and/or ventricular (figure 4A,B) abnormalities (n= 20, 19%), brainstem (figure 5) or cerebellar (figure 6A) abnormalities (n= 16, 15%) and white matter (figure 6B) abnormalities (n= 16, 15%). Abnormal brain findings were identified in 42 (40%) children with ANSD on MRI; 7 (17%) were found in children with unilateral ANSD and 35 (83%) were identified in bilaterally affected cases (p=0.116).

Table 3.

Central nervous system abnormalities on MRI (n= 106 brains).

| Abnormality | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Prominent Temporal Hornsa | 33 (16) |

| CSF and/or Ventricular abnormalities | 20 (19) |

| Brainstem / Cerebellum | 16 (15) |

| White matter changes | 16 (15) |

| Cerebrum / Midbrain | 7 (7) |

| Dandy-Walker malformationb | 4 (4) |

| CNS myelination abnormality | 3 (3) |

| Chiari Type I malformationb | 2 (2) |

| Otherc | 10 (9) |

Each brain had 2 temporal horns for a total of 212 temporal horns from 106 brains.

Included in the brainstem / cerebellum grouping.

Includes: cerebellopontine angle arachnoid cyst, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, globe abnormality (n= 2), posterior fossa arachnoid cyst, leptomeningeal enhancement, prominent perivascular spaces, microcephaly, and small optic nerve (n=2).

Figure 3.

A child with bilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) evaluated with MRI. This T2-weighted axial MRI image demonstrates bilateral prominent extra-axial CSF (*) anterior to the temporal lobes.

Figure 4.

A child with bilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) evaluated with MRI. T1 weighted sequence demonstrates (A) bilateral hydrocephalus of the lateral ventricles and (B) cerebellar hypoplasia (arrow). Lateral ventricle hydrocephalus is additionally visualized (*). Severe pontine hypoplasia is additionally present.

Figure 5.

A child with bilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) evaluated with MRI. This T1-weighted sagittal image demonstrates a Dandy-Walker spectrum variant (arrow), with associated dysplastic appearing pons and corpus callosum agenesis (*).

Figure 6.

A child with bilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) evaluated with MRI. (A) 3D constructive interference in the steady state (CISS) sequence demonstrates right cerebellar hypoplasia. (B), FLAIR sequence demonstrates bilateral periventricular signal abnormality and cysts consistent with periventricular leukomalacia (arrows).

Relationships between findings on MRI (labyrinthine or brain/CSF) or CT and the medical history were sought (Table 4). Overall, there were no significant relationships between any of the imaging findings listed above and the medical history except for gestational age, NICU admission, and mechanical ventilation, which were associated with BCNC size on CT (p< 0.0001, p< 0.0001 and p< 0.003, respectively) and history of mechanical ventilation and white matter changes on MRI (p< 0.02). Specifically, children who were born prematurely, graduates of the NICU or underwent mechanical ventilation were less likely to have either a small or absent BCNC and were more likely to have a normal sized BCNC. Additionally, children having undergone mechanical ventilation were less likely to have white matter abnormalities on MRI.

Table 4.

Comparison of history and imaging findings from children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder

| Historical data | MRI

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Matter Changes1 | CSF / Ventricular abnormalities1 | Brainstem / Cerebellum Abnormalities1 | Midbrain / Cerebral Abnormalities1 | Single or multiple abnormalities1 | |

|

| |||||

| Term status at birth2 | p= 0.11 | p= 0.13 | p= 1.00 | p= 0.69 | p= 1.00 |

| NICU admission3 | p= 0.78 | p= 0.32 | p= 1.00 | p= 0.70 | p= 0.79 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia4 | p= 0.75 | p= 0.38 | p= 0.32 | p= 1.00 | p= 0.55 |

| Mechanical ventilation5 | p< 0.02 | p= 0.58 | p= 1.00 | p= 0.67 | p= 0.36 |

| CT

|

|||||

| Bilateral Cochlear dysplasia1 | BCNC6 size1 | Facial Nerve canal size1 | Single or multiple abnormalities1 | ||

|

|

|||||

| Term status at birth2 | p= 0.50 | p< 0.0001 | p= 0.51 | p= 0.54 | |

| NICU graduate3 | p= 0.30 | p< 0.0001 | p= 0.51 | p= 1.00 | |

| Hyperbilirubinemia4 | p= 1.00 | p= 0.75 | p= 1.00 | p= 0.45 | |

| Mechanical Ventilation5 | p= 0.45 | p< 0.003 | p= 1.00 | p= 1.00 | |

Fisher exact test was used to search for associations.

Statistical significance was set to ≤ 0.05.

Both the presence and absence of the finding was considered.

Premature or full term at the time of birth.

NICU graduate or did not require NICU admission after birth.

Any perinatal history of hyperbilirubinemia.

Any history of mechanical ventilation.

Bony cochlear nerve canal/cochlear aperture

Discussion

Results of the present study report the imaging findings of 118 children diagnosed with ANSD. The majority of children (n=107) underwent MRI imaging as part of their evaluation; 31 underwent additional selective use of CT. The 11 remaining children had CT imaging investigations as their sole auditory imaging evaluation, and most of these were carried out very early in the series. Overall, children in our population with bilateral ANSD had a wide range of risk factors (Table 1) that were consistent with previous reports (3,4,31-34). These included prematurity, NICU stay after birth, mechanical ventilation and hyperbilirubinemia. By contrast, children with unilateral ANSD were less likely to have these risk factors. One possible explanation for the observed association of a complicated medical history with cases of bilateral ANSD is that this condition often times represents an acquired lesion, resulting from the complications of prematurity. While a NICU admission requirement was not found to be statistically associated with bilateral ANSD, the trend was towards association. Conversely, cases of unilateral ANSD might imply an unidentified de novo lesion, thus sparing the contralateral auditory system.

Forty-three (36%) of 118 children in this group with ANSD have received cochlear implants to date, nearly all in one ear. The unilateral nature of most implantations in this group of children probably relates to some of the shortcomings in our current knowledge regarding auditory performance in this group of children.

One of the major finding of the present study was the relatively high incidence of abnormal MRI findings among children with ANSD. Nearly 65% of children with ANSD in the present study had one or more abnormal findings on MRI. By comparison, published reports of MRI evaluations among children with SNHL find that between 30 -33% of studies demonstrate an abnormality (22,23,35). A closer look at the type of abnormality identified in this cohort of children is also very revealing. In the present study, cochlear and vestibular labyrinthine dysplasias were uncommon, being detected in only 11 (10%) and 7 (7%) cases, respectively. By comparison, previous works report inner ear malformations in up to 32% of children with SNHL (19,21). Thus, while the general population of children with SNHL have either normal temporal bone structures or some variety of inner ear malformation that might include cochlear or vestibular dysplasia, children with ANSD are much less likely to have such inner ear malformations. This finding was not unexpected given the fact that the diagnosis of ANSD requires electrophysiological evidence of preserved cochlear function and disordered neural conduction. That preserved cochlear and organ of Corti morphology has been described in the temporal bones of patients with ANSD (14,36-38) is in agreement with our findings. Furthermore, cochlear and vestibular malformations that preclude normal hair cell function and the generation of OAEs and/or CMs would not be expected to produce the ANSD phenotype clinically.

Unique to the present investigation was the relatively high incidence of CND and other central nervous system findings on MRI. Abnormal or deficient cochlear nerves were identified in 28% of ears with ANSD on MRI in our study population. In an earlier study, our group found CND in 18% of children with ANSD (15). Other imaging studies report the frequency of CND to be between 2 and 28% of children with various types of SNHL (19,21,22,39-41). That our population consists exclusively of children with ANSD makes the relatively high rate of CND understandable.

In the present study as well as previous studies (15,17,18), a small IAC (<3mm in diameter, Figure 2) and/or BCNC (<1.3 mm) were both significantly correlated with the identification of CND. However, 38% (n=13) of ears with absent nerves (n=34) were found in the setting of a normal size IAC and 12% (n=4) were found in the setting of a normal BCNC (n= 33). This indicates that a small or stenotic IAC increases the probability of identifying CND but that a normal IAC does not rule out such a possibility. While a closed BCNC effectively rules out the possibility of cochlear nerve integrity, a patent aperture does not guarantee it. Although CT can measure IAC diameter and BCNC patency, it cannot directly identify cochlear nerve integrity like MRI. Given the importance of identifying CND in the management of children with ANSD, these results suggest that MRI rather than CT should be the initial imaging choice for children with ANSD. When MRI demonstrates the IAC to be small, resolution may limit cochlear nerve assessment. In these cases, supplementary CT can help identify a closed BCNC. However, in some cases, the CT scan identifies a patent BCNC making cochlear nerve status indeterminate (17,18).

Examination of the CP angle cistern anatomy found greater than half (58%) of the ears with CND had two identifiable nerves. Over half (63%) of these ears had absent cochlear nerves upon examination of the IAC. Thus, a normal compliment of nerves in the CP angle cistern does not rule out intracanalicular CND, including the possibility of complete absence of the cochlear nerve. Given the limitations of CT imaging in defining cochlear nerve integrity outlined above, these results again suggest MRI should be the initial imaging choice in children with ANSD. Furthermore, dedicated evaluation of the IAC contents should be included as part of an MRI when information regarding cochlear nerve integrity is sought.

An absent cochlear nerve would be a deterrent to ipsilateral cochlear implantation (15,19) making identification of this anomaly extremely important for surgical planning and overall treatment strategy. Cochlear nerves that are present but small or abnormal may benefit from cochlear implantation (15,19,42). Additionally, Walton et al. (41) found that children with ANSD and normal cochlear nerves attained better outcomes than children with ANSD and abnormal cochlear nerves. Unfortunately, image resolution remains a limiting factor in evaluating some children with CND, especially those cases where the IAC is small (17). Future studies should attempt to improve image resolution in order to better assess this anomaly.

In the present study, 40% (n= 42 of 106 MRIs) of children with ANSD had an array of intracranial findings, beyond CND, on MRI. The overall frequency of intracranial findings among our patients, although somewhat higher, is not entirely inconsistent with published reports of various SNHL populations (19,21,23,39,40). This finding is most likely explained by the fact that the population in the present study was made up exclusively of children with ANSD. While the relevance of each of the various brain findings remains to be determined, it can be surmised that the abnormal auditory system physiology documented in these children likely resulted from of the same pathological process that affected the brain on a larger scale. In the absence of definable CND in 72% of ears with ANSD, one plausible explanation is that the cochlear nerve pathology that is physiologically present is not resolvable using currently available imaging protocols and technology. For instance, if demyelination with otherwise preserved neural architecture or less than severe neuronal atrophy were present, then these changes might adversely affect neural function but be below the resolvable limits of detection given the currently available imaging protocols and equipment. Future studies should attempt to further classify and correlate the central nervous system anatomical findings in the present report with functional parameters such as speech perception scores using either acoustic or electrical stimuli as well as more detailed electrophysiological studies. Such studies may shed light on the disruptive mechanisms at play in the auditory system of children with ANSD. Imaging protocols and techniques should also be sought that can better define the pathological processes described above.

With the previous results in mind, the relatively high incidence of abnormal CT findings identified in our population (54%) was not unexpected. Our protocol calls for CT investigations to supplement MRI when abnormalities of the inner ear or a small IAC are identified. However, the use of CT alone in this population would have been expected to miss most of the brain abnormalities and all of the cases of CND in which the IAC and BCNC were of normal size. For these reasons, MRI appears to be superior to CT for imaging children with ANSD.

Is MRI justified over CT as the initial imaging modality for children with ANSD? It is clear that MRI carries an increased duration of sedation for image acquisition as well as cost when compared to CT. However, these risks and costs appear justified when contemplating further interventions such as cochlear implantation. From the data presented in this paper and others, MRI is superior to CT in identifying CND and other central nervous system anomalies in children with hearing loss (17-19,21,23). Children receiving cochlear implants in the setting of ANSD and CND have been shown to attain worse speech perception outcomes when compared to children with ANSD and normal nerves (15,17,18,41). Recently, Teagle (personal communication) found that children with ANSD having undergone cochlear implantation in the setting of an MRI abnormality had significantly lower PB-k word scores compared with children with a normal MRI. Additionally, no child in their study with ANSD and CND attained open-set speech perception. While the decision to proceed with implantation in the setting of ANSD and CND should be individualized, the prognosis for success in these children should be tempered. Additionally, MRI can reliably identify many of the inner dysplasias and malformations seen via CT (23) thereby obviating the need for ionizing radiation exposure in young children.

MRI as a procedure is more expensive when compared to CT imaging due to the higher cost of image acquisition and the usual requirement of sedition in young children. Parry et al. (21) found that though MRI evaluation increased the cost of imaging evaluations, an overall cost saving was realized. This was attributed to directed implantation of the most desirable ear identified by information gain exclusively by MRI evaluation. An algorithm presented by Trimble et al. (23) proposed MRI imaging as the initial imaging investigation with CT being performed only when either medical history or MRI findings identify risks of intraoperative complications. Retrospective application of this algorithm to their study cohort resulted in a theoretical reduction in the amount of ionizing radiation as well as a significant cost savings borne by the cohort (23). Further study of our cohort is needed to investigate the cost impact of our protocol.

Conclusions

This report examined the imaging finding of 118 children diagnosed with ANSD on MRI and selective use of CT. MRI identifies many abnormalities in children with ANSD that are not readily discernable on CT. Developmental and acquired abnormalities of the brain, posterior cranial fossa, and cochlear nerves are not uncommonly seen in this patient population. Inner ear anomalies are well delineated using either imaging modality. Since many of the central nervous system findings identified in this study using MRI can alter the treatment and prognosis for these children, we believe that MRI is justified as the initial imaging study of choice for children with ANSD.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to recognize Patricia Roush AuD, Corrine MacPherson AuD, Sarah Martinho AuD, Jill Ritch AuD, Paula Johnson AuD, Holly Teagle, AuD, Deborah Hatch AuD, Jennifer Woodard AuD, and Lisa DiMaria, for their dedication and expertise in the care of these children. We also would like to acknowledge Harold C. Pillsbury for his continued support of this work.

Funding Source: This study was supported in part by NIDCD T32-DC005360-05

References

- 1.Berlin CI, Bordelon J, St John P, et al. Reversing click polarity may uncover auditory neuropathy in infants. Ear Hear. 1998;19:37–47. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199802000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaga K, Nakamura M, Shinogami M, et al. Auditory nerve disease of both ears revealed by auditory brainstem responses, electrocochleography and otoacoustic emissions. Scand Audiol. 1996;25:233–8. doi: 10.3109/01050399609074960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rance G, Beer DE, Cone-Wesson B, et al. Clinical findings for a group of infants and young children with auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 1999;20:238–52. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starr A, Picton TW, Sininger Y, et al. Auditory neuropathy. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 3):741–53. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rance G. Auditory neuropathy/dys-synchrony and its perceptual consequences. Trends Amplif. 2005;9:1–43. doi: 10.1177/108471380500900102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis H, Hirsh SK. A slow brain stem response for low-frequency audiometry. Audiology. 1979;18:445–61. doi: 10.3109/00206097909072636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rea PA, Gibson WP. Evidence for surviving outer hair cell function in congenitally deaf ears. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:2030–4. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200311000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xoinis K, Weirather Y, Mavoori H, et al. Extremely low birth weight infants are at high risk for auditory neuropathy. J Perinatol. 2007;27:718–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlin CI, Hood L, Morlet T, et al. Auditory neuropathy/dys-synchrony: diagnosis and management. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2003;9:225–31. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs PA, Glowatzki E, Moser T. The afferent synapse of cochlear hair cells. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:452–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapin I, Gravel J. “Auditory neuropathy”: physiologic and pathologic evidence calls for more diagnostic specificity. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:707–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasunaga S, Grati M, Cohen-Salmon M, et al. A mutation in OTOF, encoding otoferlin, a FER-1-like protein, causes DFNB9, a nonsyndromic form of deafness. Nat Genet. 1999;21:363–9. doi: 10.1038/7693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varga R, Kelley PM, Keats BJ, et al. Non-syndromic recessive auditory neuropathy is the result of mutations in the otoferlin (OTOF) gene. J Med Genet. 2003;40:45–50. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahmad F, Jr, Merchant SN, Nadol JB, Jr, et al. Otopathology in Mohr-Tranebjaerg syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1202–8. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180581944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchman CA, Roush PA, Teagle HF, et al. Auditory neuropathy characteristics in children with cochlear nerve deficiency. Ear Hear. 2006;27:399–408. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000224100.30525.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berlin CI, Morlet T, Hood LJ. Auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony: its diagnosis and management. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2003;50:331–40. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(03)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adunka OF, Jewells V, Buchman CA. Value of computed tomography in the evaluation of children with cochlear nerve deficiency. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:597–604. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000281804.36574.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adunka OF, Roush PA, Teagle HF, et al. Internal auditory canal morphology in children with cochlear nerve deficiency. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:793–801. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000227895.34915.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClay JE, Booth TN, Parry DA, et al. Evaluation of pediatric sensorineural hearing loss with magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:945–52. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.9.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohlms LA, Chen AY, Stewart MG, et al. Establishing the etiology of childhood hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:159–63. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parry DA, Booth T, Roland PS. Advantages of magnetic resonance imaging over computed tomography in preoperative evaluation of pediatric cochlear implant candidates. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:976–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000185049.61770.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons JP, Mandell DL, Arjmand EM. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric unilateral and asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:186–92. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trimble K, Blaser S, James AL, et al. Computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging before pediatric cochlear implantation? Developing an investigative strategy. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:317–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000253285.40995.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klingebiel R, Bockmuhl U, Werbs M, et al. Visualization of inner ear dysplasias in patients with sensorineural hearing loss. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:574–81. doi: 10.1080/028418501127347403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchman CA, Roush PA, Teagle HFB, et al. Clinical Managmement of children with auditory neuropathy. In: Eisenberg L, editor. Clinical Managmement of Children with Cochlear implants. San Deigo, CA: Plural Publishing; 2009. pp. 633–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchman CA, Copeland BJ, Yu KK, et al. Cochlear implantation in children with congenital inner ear malformations. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:309–16. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200402000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olivares FP, Schuknecht HF. Width of the internal auditory canal. A histological study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88:316–23. doi: 10.1177/000348947908800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakashita T, Sando I. Postnatal development of the internal auditory canal studied by computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction and measurement. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:469–75. doi: 10.1177/000348949510400610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glastonbury CM, Davidson HC, Harnsberger HR, et al. Imaging findings of cochlear nerve deficiency. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:635–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deltenre P, Mansbach AL, Bozet C, et al. Auditory neuropathy with preserved cochlear microphonics and secondary loss of otoacoustic emissions. Audiology. 1999;38:187–95. doi: 10.3109/00206099909073022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starr A, Sininger Y, Nguyen T, et al. Cochlear receptor (microphonic and summating potentials, otoacoustic emissions) and auditory pathway (auditory brain stem potentials) activity in auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 2001;22:91–9. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg AL, Spitzer JB, Towers HM, et al. Newborn hearing screening in the NICU: profile of failed auditory brainstem response/passed otoacoustic emission. Pediatrics. 2005;116:933–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rance G, Cone-Wesson B, Wunderlich J, et al. Speech perception and cortical event related potentials in children with auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 2002;23:239–53. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madden C, Rutter M, Hilbert L, et al. Clinical and audiological features in auditory neuropathy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1026–30. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.9.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mafong DD, Shin EJ, Lalwani AK. Use of laboratory evaluation and radiologic imaging in the diagnostic evaluation of children with sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzpatrick DB, Hooper RE, Seife B. Hereditary deafness and sensory radicular neuropathy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:552–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1976.00780140084010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merchant SN, McKenna MJ, Nadol JB, Jr, et al. Temporal bone histopathologic and genetic studies in Mohr-Tranebjaerg syndrome (DFN-1) Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:506–11. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson EG, Hinojosa R. Aplasia of the cochlear nerve: a temporal bone study. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:790–5. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lapointe A, Viamonte C, Morriss MC, et al. Central nervous system findings by magnetic resonance in children with profound sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:863–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russo EE, Manolidis S, Morriss MC. Cochlear nerve size evaluation in children with sensorineural hearing loss by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walton J, Gibson WP, Sanli H, et al. Predicting cochlear implant outcomes in children with auditory neuropathy. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29:302–9. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318164d0f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nadol JB, Jr, Xu WZ. Diameter of the cochlear nerve in deaf humans: implications for cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:988–93. doi: 10.1177/000348949210101205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]