Dietary cholesterol levels control follicle stem cell proliferation in the Drosophila ovary via regulation of Hedgehog protein localization.

Abstract

A healthy diet improves adult stem cell function and delays diseases such as cancer, heart disease, and neurodegeneration. Defining molecular mechanisms by which nutrients dictate stem cell behavior is a key step toward understanding the role of diet in tissue homeostasis. In this paper, we elucidate the mechanism by which dietary cholesterol controls epithelial follicle stem cell (FSC) proliferation in the fly ovary. In nutrient-restricted flies, the transmembrane protein Boi sequesters Hedgehog (Hh) ligand at the surface of Hh-producing cells within the ovary, limiting FSC proliferation. Upon feeding, dietary cholesterol stimulates S6 kinase–mediated phosphorylation of the Boi cytoplasmic domain, triggering Hh release and FSC proliferation. This mechanism enables a rapid, tissue-specific response to nutritional changes, tailoring stem cell divisions and egg production to environmental conditions sufficient for progeny survival. If conserved in other systems, this mechanism will likely have important implications for studies on molecular control of stem cell function, in which the benefits of low calorie and low cholesterol diets are beginning to emerge.

Introduction

The long-term survival and function of stem cells depend on spatial cues, secreted signals, and structural support generated by the local stem cell microenvironment, or niche (Morrison and Spradling, 2008). Tremendous progress has been made in identifying the niche-generated factors necessary for stem cell regulation and how these factors interact with proteins expressed within the stem cells themselves. In contrast, very little is known about the mechanisms that control stem cell responses to systemic changes within an organism. For example, stem cells proliferate in response to extrinsic factors such as feeding, but the mechanisms that relay systemic nutritional changes to the local stem cell niche have not been well defined.

In Drosophila melanogaster, proliferation rates of two ovarian stem cell populations, germline stem cells (GSCs) and epithelial follicle stem cells (FSCs), are controlled by nutritional signals (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001). GSCs divide asymmetrically to self-renew and produce a differentiating daughter cell that generates a 16-cell germline cyst, including one cell that is fated to become the oocyte (Fig. 1 A). Developing cysts are enveloped by follicular epithelial cells that are derived from FSCs, resulting in the formation of a follicle cell–germ cell unit called an egg chamber (Fig. 1 A; King, 1970; Spradling, 1993). Under conditions in which flies are fed only simple sugars, GSC and FSC proliferation is arrested to ensure that eggs are not produced when the environment lacks sufficient nutrients to support normal progeny development (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001). The starvation response is rapid, with cessation of egg production within 24 h of switching flies to nutrient-restricted food. This effect is reversible, as subsequent feeding of nutrient-restricted flies with rich food activates GSC and FSC proliferation, and normal numbers of eggs are produced within 36–48 h (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001). Initiation of egg laying after a period of nutrient deprivation depends on the insulin signaling pathway, which promotes GSC proliferation (LaFever and Drummond-Barbosa, 2005; Hsu et al., 2008; Hsu and Drummond-Barbosa, 2009b, 2011). In contrast, the nutrient-dependent mechanisms that activate FSC proliferation have not been identified.

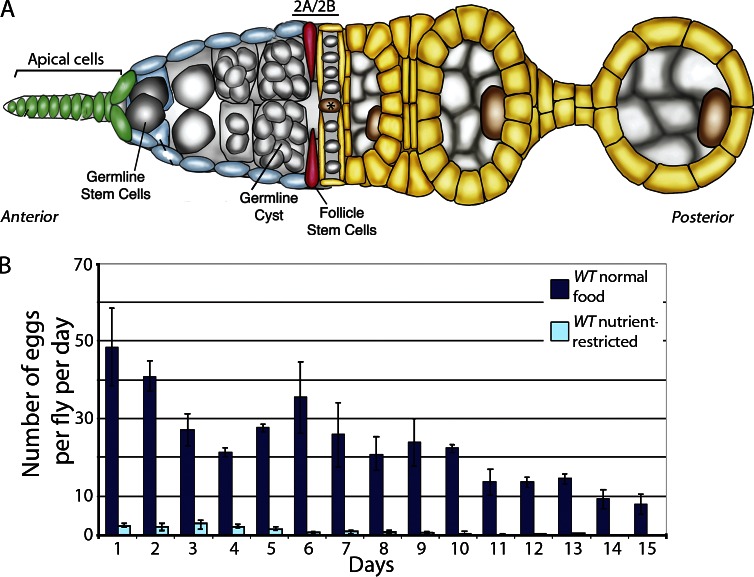

Figure 1.

Nutrient restriction inhibits egg production in flies. (A) Schematic of early oogenesis. GSCs (gray) contact a cellular niche composed of apical cells (green) found at the anterior of the germarium. FSCs (red) reside three to five cell diameters posterior to apical cells and generate daughter cells (yellow) that form an epithelial layer around 16-cell germline cysts (gray), producing follicles called egg chambers that generate mature eggs in 7 d. The asterisk indicates flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. (B) Eggs laid/fly/day were scored daily for nutrient-restricted or fed WT flies. Error bars represent standard deviations.

When abundant nutrients are available, FSC proliferation is controlled through a convergence of Hedgehog (Hh), TGF-β, and Wnt family signals produced by the anterior-most cells within the ovary (apical cells) and Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription signals induced by cells located to the posterior of FSCs (Fig. 1 A; Forbes et al., 1996a,b; Zhang and Kalderon, 2000, 2001; Song and Xie, 2003; Kirilly et al., 2005; Vied et al., 2012). FSCs express receptors for each of these growth factors and proliferate in response to the presence of ligand in the local niche. The FSC proliferation response is extremely sensitive to the levels of growth factor available. Increased levels of ligand or receptor activity result in excessive FSC proliferation and the accumulation of follicle cells in long cellular stalks between egg chambers. Conversely, too little signaling prevents sufficient FSC proliferation and leads to the generation of egg chambers with gaps in the epithelium, loss of stalk cells, and inappropriate packing of germline cysts (Forbes et al., 1996a,b; Zhang and Kalderon, 2000, 2001; Song and Xie, 2003; Kirilly et al., 2005; Vied et al., 2012).

To maintain the precise rates of FSC proliferation necessary for normal egg chamber development, growth factor levels are tightly regulated through control of ligand production, secretion, and delivery (King et al., 2001; Kirilly et al., 2005; López-Onieva et al., 2008; Guo and Wang, 2009; Hayashi et al., 2009; Szakmary et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010). Recently, we identified an additional mechanism for regulation of Hh levels in the FSC niche. The transmembrane protein Boi is expressed on the surface of apical cells where it binds directly to Hh, sequestering it away from the FSC niche. In boi mutants, Hh is released from apical cells and accumulates near FSCs, where it promotes proliferation (Hartman et al., 2010). Our results indicate that the primary function of Boi in FSC proliferation control is to limit access of Hh ligand to FSCs, thus defining growth factor sequestration as an important mechanism for regulating stem cell proliferation (Hartman et al., 2010). Moreover, these observations suggest that FSC proliferation in wild-type (WT) ovaries may be controlled by triggered release of Hh in response to changes in signals that influence egg production. Here, we demonstrate that Hh sequestration and release are controlled by diet and define the signaling pathway that functions within apical cells to promote Hh release and FSC proliferation control.

Results

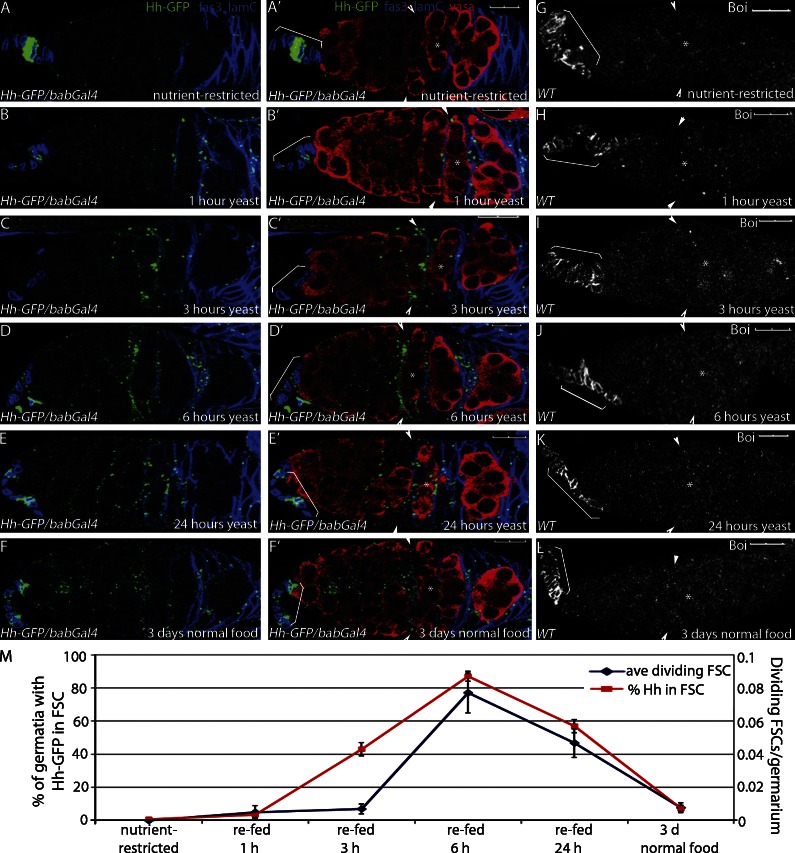

To test whether Hh sequestration and release are controlled by nutritional changes, young adult WT females were raised on normal food and then transferred to “nutrient-restricted” conditions consisting only of water and simple sugars (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001). Flies can survive on this diet for up to 75 d (mean life span: 30.5 d [restricted] and 40.5 d [fed]; Fig. S1; Hassett, 1948), but they lack essential nutrients, including amino acids, lipids, and vitamins that are necessary for egg production (Fig. 1 B; Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001). Stem cell proliferation and egg production are stimulated in nutrient-restricted female flies by refeeding the flies yeast, which supplements a sugar-only diet with additional essential nutrients (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001). In nutrient-restricted flies expressing Hh-GFP under control of an apical cell–specific Gal4 transcriptional activator (Hh-GFP/bab-Gal4; Fig. S2, A and B; Cabrera et al., 2002; Hartman et al., 2010), Hh-GFP localized primarily to the surface of apical cells (Fig. 2 A) and was rarely seen in other cells within the germarium. By 1 h after feeding, most of the Hh-GFP was released from apical cells (Fig. 2 B). Hh-GFP concentrated in somatic cells in the center of the germarium by 3 h after feeding and peaked by 6 h after feeding (Fig. 2, C and D). These cells exhibit the hallmarks of FSCs, including their location on the surface of the germarium immediately anterior to the first flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border, a characteristic triangular morphology, and low expression of the follicle cell marker Fas3 (Fig. 1 A; Margolis and Spradling, 1995; Zhang and Kalderon, 2001; Nystul and Spradling, 2007, 2010). Moreover, FSCs are known to be particularly responsive to Hh signaling (Forbes et al., 1996a,b; Zhang and Kalderon, 2000, 2001), supporting the idea that Hh accumulates predominantly within FSCs after release from apical cells. At all time points examined, Boi was expressed on the surface of apical cells, suggesting that the mechanism of Hh release is not caused by loss of Boi from the plasma membrane (Fig. 2, G–L). Production of new Hh-GFP was not observed until 6 h after refeeding (Fig. 2 D), indicating that feeding triggered release of Hh molecules bound to Boi on the surface of apical cells rather than promoting Hh production or secretion. 3 d after refeeding, Hh-GFP localized primarily to the surface of apical cells (Fig. 2 F). A similar time course of Hh release was observed when an antibody that detects endogenous Hh protein was applied to ovaries isolated from nutrient-restricted or refed flies (Fig. S3, A–D). Thus, Hh protein is released from the producing cells in response to nutrient stimulation.

Figure 2.

Refeeding nutrient-restricted flies stimulates Hh release and FSC proliferation. (A–G) Nutrient-restricted WT flies expressing Hh-GFP in the apical cells (Hh-GFP/bab-Gal4) were refed yeast for the times indicated. (A–F) Follicle cells (Fas3) and apical cells (Lamin C [lamC]) are both labeled in blue to enable mapping of Hh localization. Hh-GFP is also shown. (A′–F′) Same images as A–F with germ cells shown (Vasa). (G–L) Boi localization in apical cells is indicated with brackets in nutrient-restricted (G) and refed (H–L) flies. (A–L) Asterisks mark the flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. Arrowheads indicate FSCs. Brackets indicate apical cells. Bars, 10 µM. (M) Mean numbers of dividing FSCs and Hh-GFP localization in the FSCs are shown. Error bars represent SEs.

FSCs proliferate in response to Hh (Forbes et al., 1996a; Zhang and Kalderon, 2001), suggesting that nutrient-stimulated Hh accumulation in FSCs might mediate FSC proliferation upon feeding. To measure proliferation, FSCs were identified by nuclear markers that are expressed at higher levels in FSCs and their progeny relative to other cells in the germarium (follicle cell nuclear antigens [FC-NAs]; Fig. S4; König et al., 2011). In addition to marking FSC location and nuclear morphology, high nuclear marker expression correlated precisely with marked FSC clones generated by mitotic recombination using an FSC and follicle cell–specific Gal4 transcriptional activator and upstream activation sequence (UAS)-GFP (109-30-Gal4; Figs. S2, C and D; and S4; Hartman et al., 2010). This suggests that nuclear markers can be used to accurately label FSCs and, in contrast to lineage tracing by mitotic recombination, allow the scoring of proliferation in all FSCs of the germarium upon feeding. Germaria also were immunostained with Fas3 to label differentiating follicle cells and anti–phosphohistone-H3, a mitotic mark that is commonly used to identify dividing cells in the germarium (Fig. S4). The time course of FSC proliferation precisely tracked with accumulation of Hh-GFP in FSCs, with increased FSC proliferation observed by 1 h after feeding and peak numbers of dividing FSCs at 6 h (Fig. 2 M). Similar differences in FSC proliferation in nutrient-restricted versus fed flies were observed when germaria were labeled with BrdU (unpublished data; O’Reilly et al., 2008). These results support a model in which feeding triggers increased Hh levels in FSCs to initiate follicle cell production after a nutrient restriction–induced arrest.

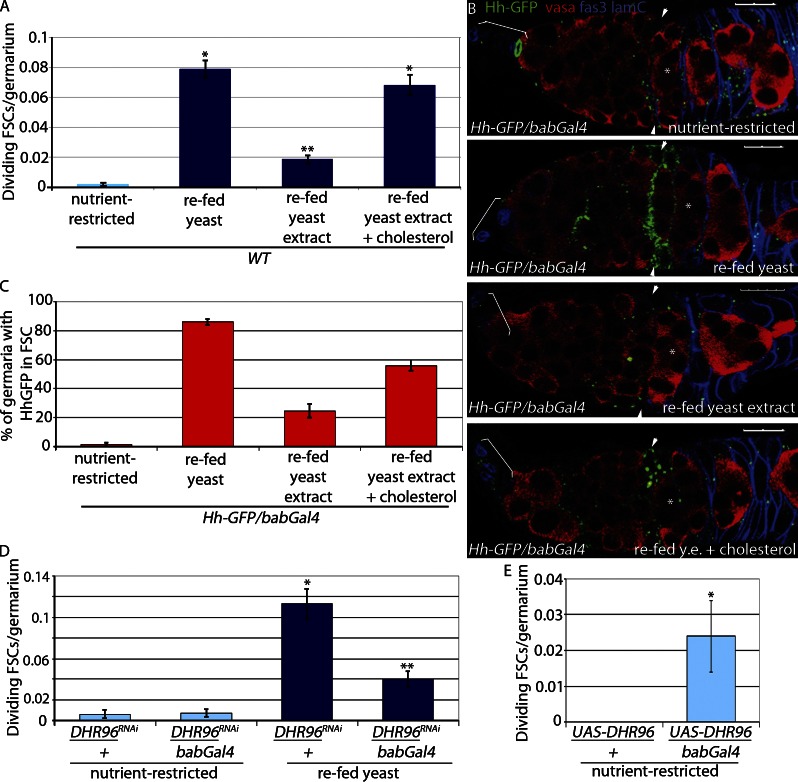

Insulin is a key regulator of proliferation of multiple stem cell populations, including GSCs (LaFever and Drummond-Barbosa, 2005; Hsu and Drummond-Barbosa, 2009a; Mairet-Coello et al., 2009; Chell and Brand, 2010; Mathur et al., 2010; McLeod et al., 2010; Michaelson et al., 2010; Sousa-Nunes et al., 2010; O’Brien et al., 2011). However, loss of insulin receptor (InR) expression in FSCs does not affect proliferation (LaFever and Drummond-Barbosa, 2005), and insulin stimulation of germaria cultured ex vivo increases GSC proliferation with no effect on FSC proliferation (unpublished data; Morris and Spradling, 2011). FSC proliferation increased dramatically in females fed complete yeast, indicating that a critical nutrient is present in yeast. In contrast, only a modest response was observed in flies fed yeast extract (Fig. 3 A and Table 1; Horner et al., 2009; Bujold et al., 2010), a rich source of soluble components of yeast, including vitamins, minerals, and the complex sugars and amino acids that are known to stimulate insulin signaling in flies (Géminard et al., 2009; Sousa-Nunes et al., 2010; Musselman et al., 2011). Moreover, reduced expression of the InR in apical cells (InR RNAI/bab-Gal4) had no effect on feeding-stimulated Hh release, FSC proliferation, or GSC proliferation (Fig. S5, A–D). In contrast, reduced InR expression in apical cells suppressed proliferation of GSCs and FSCs in well-fed flies (Fig. S5, E and F). These results suggest that insulin is not the primary signaling pathway that mediates the feeding response of nutrient-restricted flies but is essential for maintenance of stem cell proliferation under steady-state conditions. Importantly, these observations suggest that an insulin-independent, hydrophobic component of yeast must act as the primary trigger for FSC proliferation.

Figure 3.

Cholesterol triggers Hh release. (A) Nutrient-restricted WT flies were refed for 6 h with yeast or yeast extract (y.e.) ± 0.2 mg/g cholesterol or ethanol vehicle control. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.00001 versus nutrient-restricted WT. **, P < 0.00001 versus WT refed yeast (n = 1,320–2,113; Table 1). (B and C) Nutrient-restricted WT flies expressing Hh-GFP in apical cells (Hh-GFP/bab-Gal4) were refed for 6 h with yeast or yeast extract ± 0.2 mg/g cholesterol or ethanol vehicle control and stained for Hh-GFP. (B) Follicle cells and apical cells are both labeled in blue (Fas3 and Lamin C [lamC], respectively), and germ cells are labeled red (Vasa). Asterisks indicate flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. Arrowheads indicate FSCs. Brackets indicate apical cells. Bars, 10 µM. (C) The percentage of germaria with Hh-GFP localized to FSCs was scored (n = 85–195). (D) Nutrient-restricted DHR96RNAi/bab-Gal4 and DHR96RNAi/+ flies were refed yeast for 6 h. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.00001 versus nutrient-restricted DHR96 RNAi/+. **, P < 0.00001 versus refed DHR96 RNAi/+ (n = 779–1,194; Table 1). (E) UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4 and UAS-DHR96/+ flies were nutrient restricted for 3 d. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.005 versus nutrient-restricted UAS-DHR96/+ (n = 184 and 251; Table 1). Error bars represent SEs.

Table 1.

Quantification of FSC proliferation

| Genotype | Control genotype | Scoring average | P-value | ||||

| Starve conditions | Refed yeast 6 h | Starve vs. control starve | Starve vs. control refed | Refed vs. control starve | Refed vs. control refed | ||

| w1118 | w1118 | 0.0015 (0.001); n = 1,948 | 0.09 (0.006); n = 2,113 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| boie01708 | w1118 | 0.054 (0.012); n = 370 | 0.13 (0.016); n = 437 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.023 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.01 |

| bab-Gal4/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 457 | 0.088 (0.012); n = 522 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| DHR96 RNAi/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.0017); n = 825 | 0.113 (0.011); n = 779 | ≤0.99 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.15 |

| DHR96 RNAi/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.005 (0.002); n = 1,014 | 0.039 (0.006); n = 1,194 | ≤0.4 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 |

| UAS-DHR96/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0 (0); n = 184 | 0.102 (0.019); n = 264 | ≤0.56 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.52 |

| UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.024 (0.01); n = 251 | 0.097 (0.01); n = 487 | ≤0.005 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.62 |

| Hh RNAi/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0 (0); n = 429 | 0.135 (0.016); n = 438 | ≤0.38 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.02 |

| Hh RNAi/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.004 (0.004); n = 278 | 0.05 (0.008) n = 699 | ≤0.61 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.008 |

| boie; bab-Gal4/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.05 (0.01); n = 418 | 0.099 (0.017); n = 314 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.59 |

| boie; DHR96 RNAi/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.051 (0.008); n = 800 | 0.11 (0.018); n = 290 | ≤0.008 | ≤0.008 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.31 |

| boie; DHR96 RNAi/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.038 (0.007); n = 710 | 0.074 (0.011); n = 569 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.0002 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.39 |

| S6K RNAi/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.005 (0.002); n = 1,037 | 0.093 (0.01); n = 724 | ≤0.39 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.76 |

| S6K RNAi/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 493 | 0.042 (0.007); n = 935 | ≤0.99 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.0004 |

| UAS-S6K-TE/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.003 (0.002); n = 1,132 | na | ≤0.72 | ≤0.00001 | na | na |

| UAS-S6K-WT/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.005 (0.003); n = 595 | na | ≤0.43 | ≤0.00001 | na | na |

| UAS-S6K-TE/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.018 (0.008); n = 277 | na | ≤0.02 | <0.0002 | na | na |

| UAS-S6K-STDE/+ | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.003 (0.002); n = 975 | na | ≤0.74 | ≤0.00001 | na | na |

| UAS-S6K-STDE/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.016 (0.005); n = 708 | na | ≤0.02 | ≤0.00001 | na | na |

| S6K RNAi/+; UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4 | bab-Gal4/+ | 0.006 (0.003); n = 518 | na | ≤0.33 | ≤0.00001 | na | na |

| S6K RNAi/+; UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4 | UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4 | 0.006 (0.003); n = 518 | na | <0.03 | na | na | na |

| boie; S6K RNAi/+; +/TM2 | boie; S6KRNAi/+; +/TM2 | 0.015 (0.006); n = 337 | na | na | na | na | na |

| boie; S6K RNAi/+; bab-Gal4/TM2 | boie; S6KRNAi/+; +/TM2 | 0.012 (0.008); n = 163 | na | ≤0.789 | na | na | na |

| InR-JF01183/+ | InR-JF01183/+ | 0.001 (0.001); n = 830 | 0.057 (0.009); n = 716 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| InR-JF01183/bab-Gal4 | InR-JF01183/+ | 0.003 (0.002); n = 750 | 0.061 (0.01); n = 539 | ≤0.36 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.77 |

| InR-JF01482/+ | InR-JF01482/+ | 0 (0); n = 252 | 0.078 (0.013); n = 448 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| InR-JF01482/bab-Gal4 | InR-JF01482/+ | 0 (0); n = 146 | 0.091 (0.015); n = 364 | ≤0.999 | ≤0.0004 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.51 |

| 109-53-Gal4/+ | 109-53-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 518 | 0.096 (0.012); n = 634 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| DHR96 RNAi/+ | 109-53-Gal4/+ | 0 (0); n = 386 | 0.088 (0.013); n = 513 | ≤0.37 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.64 |

| DHR96 RNAi/109-53-Gal4 | 109-53-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 444 | 0.048 (0.009); n = 543 | ≤0.99 | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | <0.002 |

| 109-30-Gal4/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 455 | 0.067 (0.009); n = 715 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| smo RNAi/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.005 (0.004); n = 336 | 0.086 (0.009); n = 924 | ≤0.37 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | <0.16 |

| smo RNAi/109-30-Gal4 | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.003 (0.002); n = 1,069 | 0.026 (0.004); n = 1,294 | ≤0.73 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.00001 |

| boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0 (0); n = 314 | 0.118 (0.016); n = 398 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| boie; UAS-BoiΔFN1/+ | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.032 (0.01); n = 308 | 0.056 (0.01); n = 550 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | <0.0006 |

| boie; UAS-BoiΔFN1/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.029 (0.01); n = 243 | 0.043 (0.009); n = 534 | ≤0.002 | ≤0.00001 | <0.0002 | <0.00001 |

| boie; UAS-BoiΔcyto/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.002 (0.002); n = 409 | 0.025 (0.007); n = 563 | ≤0.47 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.005 | <0.00001 |

| boie; UAS-BoiΔcyto-GFP/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.003 (0.002); n = 621 | 0.028 (0.007); n = 565 | ≤0.35 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.003 | <0.00001 |

| boie; UAS-BoiΔcterm/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.003 (0.002); n = 755 | 0.014 (0.004); n = 725 | ≤0.30 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.034 | <0.00001 |

| boie; UAS-BoiΔcterm-GFP/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0 (0); n = 157 | 0.009 (0.006); n = 218 | ≤0.99 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.096 | <0.00001 |

| boie; EP-Ihog/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.005 (0.003); n = 753 | 0.077 (0.012); n = 480 | ≤0.22 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | <0.04 |

| boie; UAS-Boi983A/bab-Gal4 | boie; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4 | 0.004 (0.003); n = 460 | 0.022 (0.005); n = 962 | ≤0.28 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.008 | ≤0.00001 |

| Refed yeast extract 6 h | Starve vs. control refed yeast extract | Refed yeast extract vs. control starve | Refed yeast extract vs. control refed yeast extract | ||||

| w1118 | w1118 | 0.002 (0.001); n = 1,538 | 0.019 (0.003); n = 1,542 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| 109-30-Gal4/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 455 | 0.018 (0.009); n = 217 | na | <0.024 | <0.024 | na |

| smo RNAi/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.005 (0.004); n = 336 | 0.014 (0.005); n = 509 | na | ≤0.27 | ≤0.27 | na |

| smo RNAi/109-30-Gal4 | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.003 (0.002); n = 1,069 | 0.021 (0.009); n = 235 | ≤0.42 | ≤0.01 | ≤0.11 | ≤0.48 |

| Refed yeast extract with cholesterol 6 h | Starve vs. control refed cholesterol | Refed cholesterol vs. control starve | Refed cholesterol vs. control refed cholesterol | ||||

| w1118 | w1118 | 0.002 (0.001); n = 1,538 | 0.068 (0.007); n = 1,320 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| 109-30-Gal4/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.002 (0.002); n = 455 | 0.096 (0.014); n = 438 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| smo RNAi/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.005 (0.004); n = 336 | 0.13 (0.018); n = 346 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| smo RNAi/109-30-Gal4 | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.003 (0.002); n = 1,069 | 0.023 (0.007); n = 514 | ≤0.42 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.00001 |

| Refed yeast extract 6 h | Refed yeast extract with cholesterol 6 h | Refed yeast extract vs. control refed yeast extract | Refed yeast extract vs. control refed cholesterol | Refed cholesterol vs. control refed yeast extract | Refed cholesterol vs. control refed cholesterol | ||

| w1118 | w1118 | 0.019 (0.003); n = 1,542 | 0.068 (0.007); n = 1,320 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| 109-30-Gal4/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.018 (0.009); n = 217 | 0.096 (0.014); n = 438 | na | ≤0.0002 | ≤0.0002 | na |

| smo RNAi/+ | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.014 (0.005); n = 509 | 0.13 (0.018); n = 346 | na | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.00001 | na |

| smo RNAi/109-30-Gal4 | 109-30-Gal4/+ | 0.021 (0.009); n = 235 | 0.023 (0.007); n = 514 | ≤0.48 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.29 | ≤0.00001 |

Number of germarium scored per genotype for each condition is shown (n = x). Mean numbers are shown with SE in parentheses. Two-sample Student’s t test uses for all statistical analysis. Significant differences are achieved at P ≤ 0.05. na, not applicable.

Drosophila lack the ability to synthesize cholesterol and must obtain it from the diet (Trager, 1947; Sang, 1956), suggesting it might be a key nutrient for FSC proliferation control. Consistent with this, FSC proliferation was restored in nutrient-restricted flies fed yeast extract supplemented with 0.2 mg/g cholesterol (Fig. 3 A and Table 1). Restored proliferation coincided with Hh release from apical cells and accumulation in FSCs by 6 h after feeding (Figs. 3, B and C; and S3, G–I) in a manner that is indistinguishable from that seen upon feeding flies complete yeast (Figs. 2 D and 3 B). Flies were unable to survive ingestion of cholesterol dissolved in ethanol and could not digest cholesterol in solid form or incorporated into liposomes (unpublished data). These results suggest that dietary cholesterol consumed in the context of other components of a normal diet stimulates Hh release from apical cells to drive FSC proliferation.

Cholesterol absorption and homeostasis in flies are controlled by DHR96, a cholesterol-binding nuclear hormone receptor expressed in the midgut (Horner et al., 2009; Bujold et al., 2010; Sieber and Thummel, 2012). Under nutrient restriction conditions, DHR96 mutants cannot modulate systemic cholesterol levels, resulting in larval lethality (Horner et al., 2009; Bujold et al., 2010). DHR96 is expressed at high levels in the larval midgut (FlyAtlas; King-Jones et al., 2006; Chintapalli et al., 2007), consistent with its requirement in that tissue for function. DHR96 also is expressed at high levels in the adult ovary (FlyAtlas; unpublished data; Chintapalli et al., 2007), suggesting that cholesterol levels might be sensed directly by the ovary in a manner similar to the midgut. Reducing DHR96 levels in apical cells by expressing RNAi under control of two independent apical cell–specific Gal4 drivers (bab-Gal4 and 109-53-Gal4) dramatically suppressed FSC proliferation upon refeeding (Figs. 3 D and S2 E and Table 1). This effect was caused primarily by reduced DHR96 in apical cells rather than systemic alterations in cholesterol management, as survival of larvae of this genotype on a low cholesterol diet was not affected (unpublished data), and previous work has shown that bab-Gal4 does not induce expression in the cholesterol-absorptive cells of the midgut (Cabrera et al., 2002; Sieber and Thummel, 2012). Overexpression of DHR96 in fly larvae promotes survival in starved animals (Sieber and Thummel, 2009), caused either by the ability to scavenge remaining cholesterol molecules in starved flies or the ability to activate downstream signaling in the absence of ligand. Consistent with this, increased DHR96 expression in apical cells promoted FSC proliferation in nutrient-restricted females modestly (Fig. 3 E), supporting the idea that DHR96 activity is sufficient to promote FSC proliferation.

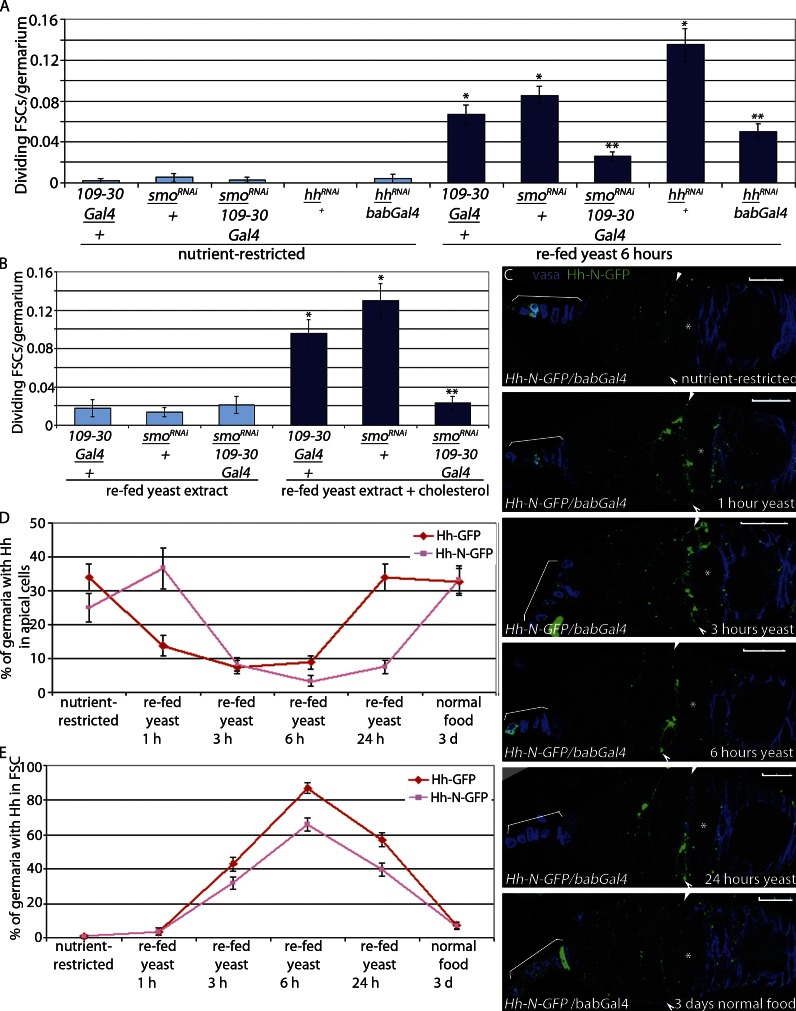

As expected, nutrient-stimulated FSC proliferation depended on Hh signaling. FSCs expressing RNAi targeted against the Hh pathway effector (109-30-Gal4/smoRNAi; Fig. S2; Hartman et al., 2010) exhibited significantly diminished proliferation in response to yeast (Fig. 4 A and Table 1) or to yeast extract plus cholesterol (Fig. 4 B and Table 1), indicating that cholesterol promotes FSC proliferation via activation of Hh signaling within FSCs. RNAi-mediated reduction of Hh in apical cells also significantly suppressed FSC proliferation after feeding (Fig. 4 A), suggesting that apical cells are the primary source of Hh ligand for FSC proliferation control. Active Hh ligand (Hh-N) is generated by cleavage of a precursor form of the protein followed by addition of a cholesterol moiety to the newly generated C terminus (Eaton, 2008), suggesting that cholesterol from the diet may be necessary for generating active, cholesterol-modified Hh-N. However, a recombinant Hh-N that cannot be cholesterol modified (Hh-N–GFP) was sequestered on the surface of apical cells in nutrient-restricted WT flies (Hh-N–GFP/bab-Gal4) and released in a manner similar to that observed for cholesterol-modified Hh-GFP (Figs. 2, A–F; and 4, C–E), indicating that cholesterol modification is not necessary for the observed effects. These results support a model in which dietary cholesterol-mediated release of active Hh from Boi promotes FSC proliferation via Smo activation within FSCs.

Figure 4.

Cholesterol-mediated Hh release is sufficient for stem cell proliferation. (A and B) Nutrient-restricted smoRNAi/109-30-Gal4, smoRNAi/+, and 109-30-Gal4/+ flies were refed yeast (A) or yeast extract ± 0.2 mg/g cholesterol (B) for 6 h. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.00001 versus nutrient-restricted 109-30-Gal4/+. **, P < 0.00001 versus smo RNAi/+ refed yeast (n = 366–1,294 [A] and n = 217–514 [B]; Table 1). (A) Nutrient-restricted hhRNAi/bab-Gal4 and hhRNAi/+ flies were refed yeast paste for 6 h. *, P < 0.00001 versus nutrient-restricted bab-Gal4/+. **, P < 0.00001 versus hhRNAi/+ refed yeast (n = 278–699; Table 1). Error bars represent SEs. (C–E) Active Hh-N–GFP is not modified by cholesterol but is retained in the apical cells in nutrient-restricted flies and released in refed flies. Asterisks indicate flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. Arrowheads indicate FSCs. Brackets indicate apical cells. Bars, 10 µM. Hh-N–GFP is lost from the apical cells (C and D) and accumulates in FSCs (C and E) at similar levels observed with cholesterol-modified Hh-GFP-C. Error bars represent SEs.

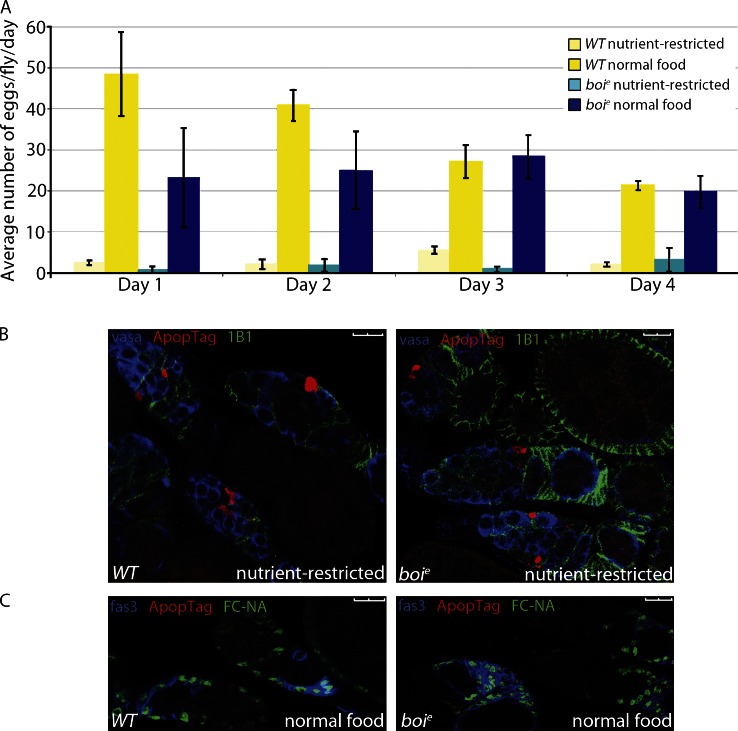

If Hh is a primary nutrient-responsive signal, Hh signaling should be sufficient to stimulate FSC proliferation, regardless of nutrition status. In boi mutant females, Hh is constitutively released from apical cells, but significant accumulation of Hh within FSCs is not observed (Fig. 5, A and B; Hartman et al., 2010). Most likely, Hh ligand is used by FSCs continuously in boi mutants rather than accumulating within FSCs after the simultaneous release of many Hh molecules upon feeding nutrient-restricted WT flies (Fig. 2). Consistent with this idea, FSCs in boi mutants continued to proliferate in nutrient-restricted flies (Fig. 5 C and Table 1). GSC proliferation also was fivefold higher in boi mutants versus WT flies under nutrient restriction conditions (Fig. 5 D), consistent with previous observations that Hh signaling can promote GSC proliferation under conditions in which normal proliferation signals are disrupted (King et al., 2001). Although boi mutant females resisted nutrient restriction, feeding with complete yeast further stimulated proliferation (Fig. 5 C). This may be a result of the additional Hh produced 6 h after feeding (Fig. 2 D) or to a second nutrient-dependent mechanism that supplements Hh signals to promote FSC proliferation. Despite constitutive proliferation of GSCs and FSCs in starved boi mutants, egg laying was negligible after 1 d because of massive apoptosis of germline cysts in the germarium similar to that seen in nutrient-restricted WT flies (Fig. 6, A and B; Buszczak and Cooley, 2000; Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001; Pritchett et al., 2009). In contrast, apoptosis of germline cysts was rarely seen in fed WT or boi mutants (Fig. 6 C). Thus, Hh release is sufficient for stem cell proliferation, but additional nutritional signals promote germline cyst survival (Terashima and Bownes, 2005; Terashima et al., 2005; Pritchett and McCall, 2012).

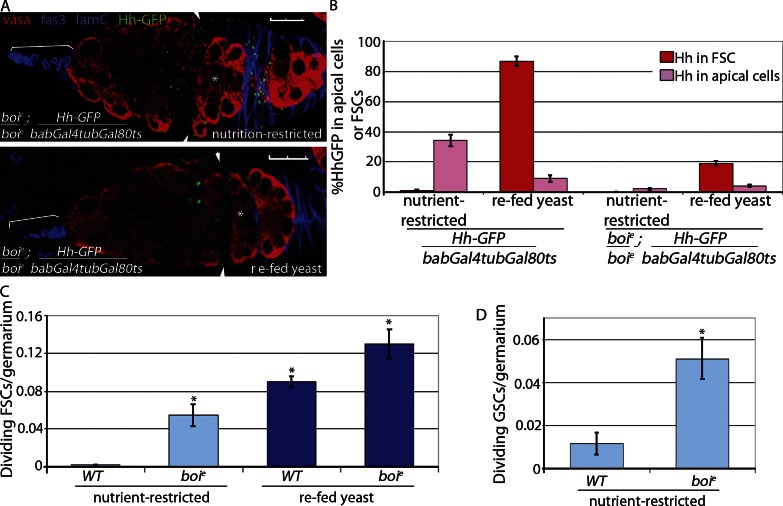

Figure 5.

FSCs proliferate in nutrient-restricted boi mutant flies. (A and B) WT and boie mutant flies expressing Hh-GFP in apical cells (Hh-GFP/bab-Gal4tubGal80ts and boie; Hh-GFP/bab-Gal4tubGal80ts) were nutrient restricted or refed yeast and stained for Hh-GFP. Follicle cells (Fas3) and apical cells (Lamin C [LamC]) are both labeled in blue to enable mapping of Hh-GFP localization, and germ cells are labeled red (Vasa; A). Asterisks indicate flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. Arrowheads indicate FSCs. Brackets indicate apical cells. Bars, 10 µM. (B) Percentage of germaria with Hh-GFP localized to apical cells or FSCs was quantified; n = 146–654. (C and D) Nutrient-restricted WT and boie mutant flies were refed yeast for 6 h. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (*, P < 0.00001 vs. nutrient-restricted WT [n = 370–2,113; Table 1]; C) or GSCs (*, P < 0.0007 vs. nutrient-restricted WT [n = 427 and 527]; D) per germarium are shown. Error bars represent SEs.

Figure 6.

Nutrient restriction blocks egg production in Boi mutant flies. (A) WT and boie mutant flies were nutrient restricted or fed yeast, and eggs laid per fly were scored daily. Error bars represent standard deviations. (B) Germaria from nutrient-restricted WT or boie mutant females were immunostained for follicle cells (1B1), germ cells (Vasa), and apoptosis (ApopTag). (C) WT or boie mutant flies on normal food lacked apoptosis (nuclei [FC-NA]), follicle cells (Fas3), and apoptosis (ApopTag). Bars, 10 µM.

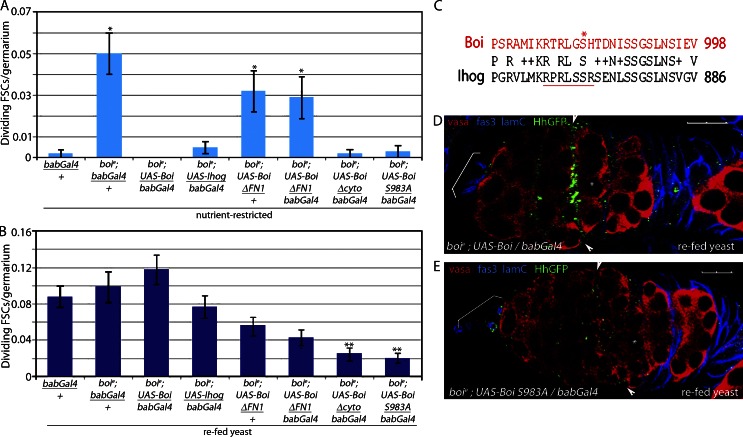

Expression of WT Boi or its close relative Ihog in apical cells was sufficient to rescue the FSC proliferation defects in nutrient-restricted boi mutants (Fig. 7 A and Table 1). Both proteins have the Hh-binding domains and Patched interaction domains required for initiating Smo-dependent signaling in flies and mammals (Cole and Krauss, 2003; McLellan et al., 2006, 2008; Tenzen et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006; Beachy et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2010; Bae et al., 2011; Izzi et al., 2011). However, Hh sequestration in well-fed flies requires only the Hh-binding domain of Boi (Hartman et al., 2010). Consistent with this observation, expression of Boi lacking the Hh-binding domain (BoiΔFN1) failed to rescue FSC proliferation in nutrient-restricted boi mutants (Fig. 7 A and Table 1). A form of Boi that retains the extracellular domain of Boi, including the Hh-binding region, but lacks the cytoplasmic domain (BoiΔcyto), suppressed FSC proliferation in nutrient-restricted boi mutants (Fig. 7 A and Table 1). However, Hh binding was not sufficient to rescue FSC proliferation upon refeeding. Expression of BoiΔcyto did not permit stimulation of FSC proliferation to WT levels upon refeeding (Fig. 7 B and Table 1), indicating that the cytoplasmic domain of Boi is necessary for feeding-stimulated Hh release. The capacity of Ihog to rescue all boi mutant defects (Fig. 7, A and B; and Table 1) suggested that the triggering mechanism is conserved in Boi and Ihog. A sequence comparison revealed that only a 28–amino acid sequence at the C terminus is conserved between the two proteins (Fig. 7 C). A form of Boi bearing a 28–amino acid C-terminal deletion (BoiΔC-term) rescued FSC proliferation defects in nutrient-restricted boi mutant flies but failed to rescue feeding-stimulated FSC proliferation, indicating a critical role for the conserved region (Table 1). This sequence includes a serine residue (S983) in Boi known to be phosphorylated in vivo in fly embryos (Zhai et al., 2008), suggesting that S983 phosphorylation might trigger Hh release. Consistent with this model, Hh release and FSC proliferation were suppressed in refed flies expressing only a mutant form of Boi bearing a mutation of S983 to alanine (BoiS983A) under conditions in which WT Boi fully rescued Hh release (Fig. 7, B, D, and E; and Table 1). As expected, BoiS983A was able to rescue Hh sequestration and FSC proliferation defects in nutrient-restricted boi mutants (Fig. 7 A and Table 1) because it retains the ability to bind to Hh (Fig. S3, E and F).

Figure 7.

Hh release is controlled by phosphorylation of a conserved serine in the Boi cytoplasmic domain. (A and B) boie mutant flies rescued with the indicated form of Boi were nutrient restricted for 3 d (A) and refed yeast for 6 h (B). (A) Forms of Boi with the ability to bind Hh rescued FSC overproliferation in nutrient-restricted boie mutants, consistent with their ability to sequester Hh. *, P < 0.00001 versus nutrient-restricted bab-Gal4/+ (n = 243–753; Table 1). (B) Forms of Boi lacking key regions of the cytoplasmic domain failed to fully rescue FSC proliferation in fed flies, consistent with a failure to release Hh. **, P < 0.00001 versus boie; UAS-boi/bab-Gal4 refed yeast (n = 314–962; Table 1). Error bars represent SEs. (C) Conserved region in the cytoplasmic domains of Boi and Ihog. S983 (asterisk) and the S6K consensus site (RxRxxSx, underlined) are indicated. The alignment was performed using NCBI BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). Letters that are identical between two sequences are reported. Those that have positive scores in the scoring matrix are displayed with a plus sign. Gaps and nonpositive scores are blank. (D and E) boie mutant flies expressing HhGFP and WT Boi (boie; HhGFP/+; UAS-Boi/bab-Gal4) accumulate Hh-GFP in FSCs after refeeding (D), whereas flies expressing BoiS983 (boie; HhGFP/+; UAS-boi983A/bab-Gal4) do not accumulate HhGFP in FSCs after refeeding (E). Hh-GFP, follicle cells (Fas3), apical cells (Lamin C [lamC]), and germ cells (Vasa) are shown. Asterisks indicate flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. Arrowheads indicate FSCs. Brackets indicate apical cells. Bars, 10 µM.

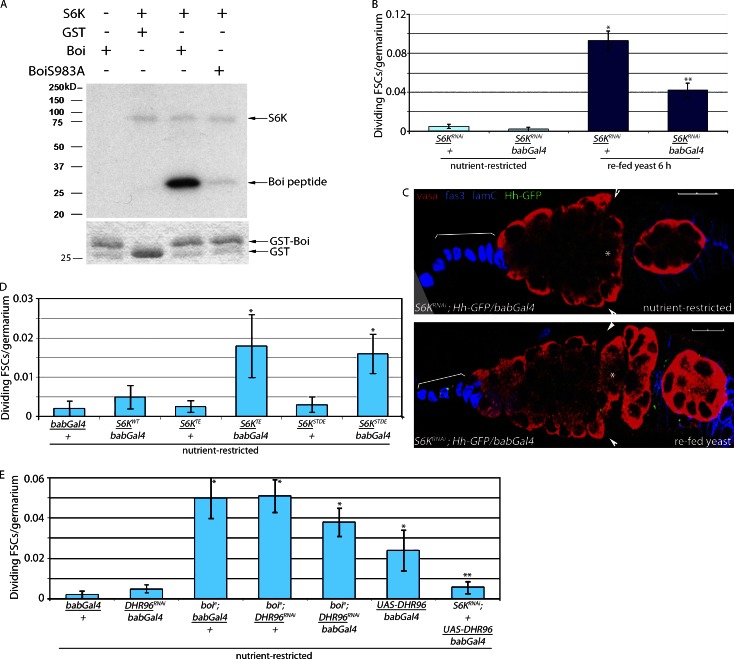

S983 matches the established consensus site for S6 kinase (S6K; Flotow and Thomas, 1992). In vitro, S6K robustly phosphorylated the cytoplasmic domain of WT Boi, but no phosphorylation was observed in BoiS983A (Fig. 8 A). S6K-mediated S983 phosphorylation is critical for FSC proliferation control because reduced expression of S6K in apical cells suppressed FSC proliferation and Hh release upon refeeding (Fig. 8, B and C; and Table 1). Conversely, expression of forms of S6K bearing mutations that promote the open active, conformation of the kinase (S6KTE and S6KSTDE) were sufficient to drive Hh-GFP release and FSC proliferation modestly in nutrient-restricted flies (Fig. 8 D and Table 1). S6K activity is regulated by dietary lipids (Castañeda et al., 2012) and by DHR96 in fly cells (Horner et al., 2009; Lindquist et al., 2011). Moreover, vertebrate orthologues of DHR96, including the vitamin D receptor, regulate S6K activity (Bettoun et al., 2002, 2004). Collectively, these data suggest that feeding stimulates DHR96-dependent activation of S6K and triggers Hh release through phosphorylation of BoiS983. Genetic epistasis experiments support this model. First, the FSC proliferation observed in starved flies overexpressing DHR96 in apical cells is suppressed by reduced expression of S6K (S6KRNAi/+;UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4; Fig. 8 E). Second, FSCs proliferate in nutrient-restricted boi mutants bearing reduced expression of DHR96 or S6K, indicating that Hh release from Boi is sufficient to drive FSC proliferation in the absence of critical upstream regulators (Fig. 8 E and Table 1).

Figure 8.

Stimulation of FSC proliferation after refeeding is S6K dependent. (A) In the presence of human S6K, BoiS983 is phosphorylated (top, third lane, bottom band). Mutation of S983 to A abrogates phosphorylation (top, forth lane), indicating that S983 is the primary site of phosphorylation. Autophosphorylation of S6K also is observed (top, second to forth lanes, top band). No signal is observed in the absence of S6K (top, first lane) or when GST alone is used as a substrate (top, second lane). (bottom) Coomassie-stained gel showing levels of GST (second lane) or GST-Boi (first, third, and forth lanes) used in the assay. (B) Nutrient-restricted S6KRNAi/bab-Gal4 and S6KRNAi/+ flies were refed yeast for 6 h. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.00001 versus nutrient-restricted S6KRNAi/+. **, P < 0.00001 versus refed S6KRNAi (n = 493–1,037; Table 1). (C) S6KRNAi flies expressing HhGFP in apical cells (S6KRNAi; HhGFP/bab-Gal4) fail to accumulate Hh-GFP in FSCs after refeeding. Hh-GFP, follicle cells (Fas3), apical cells (Lamin C [lamC]), and germ cells (Vasa) are shown. Asterisks indicate flattened germline cyst at the region 2A/2B border. Arrowheads indicate FSCs. Brackets indicate apical cells. Bars, 10 µM. (D) Activated S6K (S6KTE/bab-Gal4, S6KSTDE/bab-Gal4, S6KWT/bab-Gal4, and controls S6KTE/+ and S6KSTDE/+) flies were nutrient restricted for 3 d. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.02 versus nutrient-restricted bab-Gal4/+ (n = 277–1,132; Table 1). (E) boie; DHR96RNAi/bab-Gal4, S6KRNAi/+; UAS-DHR96/bab-Gal4, and control flies were nutrient restricted for 3 d. Mean numbers of dividing FSCs (PH3+) per germarium are shown. *, P < 0.005 versus nutrient-restricted bab-Gal4/+. **, P < 0.03 versus nutrient-restricted UAS-DHR/bab-Gal4 (n = 251–1,014; Table 1). Error bars represent SEs.

Discussion

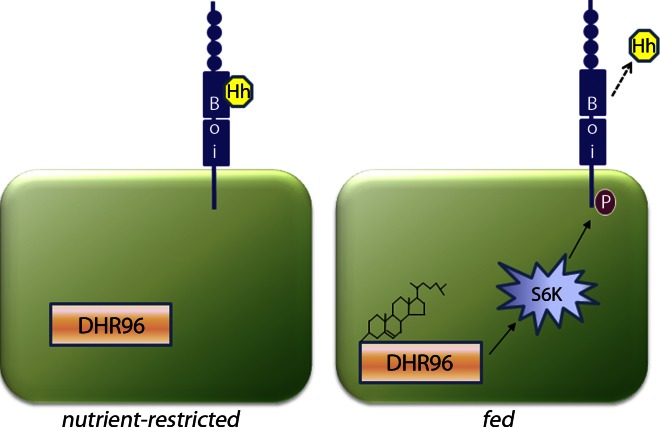

Clear benefits of dietary restriction have been demonstrated for age-related decline in stem cell function and cancer initiation and progression, implicating nutrient signals in their progression (Longo and Fontana, 2010; Omodei and Fontana, 2011). Recent work has uncovered molecular pathways that contribute to the benefits of a healthy diet (Fontana et al., 2010), but little is known about the mechanisms that interpret specific nutritional signals to control stem cell behavior. Here, we have defined a multistep molecular pathway that interprets nutritional signals to control epithelial stem cell proliferation in the fly ovary (Fig. 9). In the absence of nutrients, Boi sequesters Hh on the surface of apical cells, preventing Hh-mediated stimulation of FSC proliferation in conditions that are unfavorable for egg production. Upon feeding, increased dietary cholesterol levels are sensed by apical cells via DHR96. DHR96 then activates S6K, triggering phosphorylation of BoiS983 and reducing the ability of Boi to sequester Hh on the surface of apical cells, leading to Hh release. After release, Hh is delivered to FSCs, where it stimulates FSC proliferation in a Smo-dependent manner (Fig. 9). Potential conservation of this signal relay model in mammalian tissues will have clear implications for developing cancer therapies via inhibition of growth factor release, improving regenerative medicine strategies, and understanding normal processes, such as aging, that depend on maintenance of healthy adult stem cell populations.

Figure 9.

Cholesterol activation of DHR96 leads to S6K-dependent phosphorylation of BoiS983A, causing release of Hh from apical cells and activation of FSC proliferation. (left) Hh is sequestered by Boi in nutrient-restricted flies. Upon feeding, cholesterol binds to DHR96 and promotes phosphorylation (P) of BoiS983 via S6K activation.

Our data indicate that Boi must serve two important functions to control FSC proliferation. First, it must sequester Hh molecules, preventing them from reaching FSCs when conditions are unfavorable for egg production. Second, Boi must release Hh molecules when abundant food is present, to drive FSC proliferation rapidly and efficiently. All forms of Boi that are capable of binding to Hh rescue the ability of Boi to sequester Hh on apical cells, supporting previous observations that Hh binding is necessary for Boi function (Fig. 7 A; Yao et al., 2006; McLellan et al., 2008; Beachy et al., 2010; Hartman et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2010). In contrast, our results indicate that the Boi cytoplasmic domain is critical for Hh release (Fig. 7 B). The ability of Boi to promote feeding-dependent FSC proliferation is dramatically weakened upon cytoplasmic domain deletion or mutation of the S6K target site. These results support the model that a feeding-dependent, inside-out signaling mechanism reduces the ability of Boi to sequester Hh. By analogy to the well-studied effects of inside-out signaling on integrin conformation (Margadant et al., 2011; Ye et al., 2011), the simplest model to explain this requirement is that S983 phosphorylation alters Boi conformation, weakening Boi-Hh affinity and promoting Hh release.

Several observations suggest that Hh release is a primary mechanism for stimulating stem cell proliferation in response to dietary changes. First, loss of Smo activity within FSCs dramatically suppresses proliferation stimulated by yeast or cholesterol (Fig. 4, A and B), demonstrating that Hh signaling is required within stem cells for feeding-stimulated proliferation. Second, Hh accumulates rapidly within FSCs upon feeding, in a dynamic localization pattern that correlates precisely with feeding-stimulated FSC proliferation (Fig. 2). Finally, the remarkable ability of FSCs and GSCs in boi mutants to divide in the absence of dietary protein, lipid, complex carbohydrates, vitamins, or minerals (Fig. 5) strongly supports a model in which Hh release drives ovarian stem cell proliferation regardless of the nutritional status of the organism. The response may be extremely rapid as a result of the efficient absorption of dietary cholesterol (Horner et al., 2009) coupled with the presence of Hh poised for release on the surface of apical cells (Figs. 2, 3, and S3; Hartman et al., 2010).

One appealing possibility is that this mechanism coordinates GSC and FSC divisions after a period of starvation. According to this model, cholesterol targets a single cellular source (apical cells) to promote Hh release and stimulate proliferation of both stem cell populations simultaneously rather than requiring a complex interpretation of one or more dietary signals by each stem cell individually. This rapid, coordinated mechanism may promote initial follicle production until the slower process of protein and complex carbohydrate digestion elevates systemic insulin levels to maintain steady-state rates of egg production (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2001; LaFever and Drummond-Barbosa, 2005, O’Brien et al., 2011). This model is supported by our observations that reduced expression of InR in apical cells suppressed proliferation in well-fed, steady-state flies but had no effect on FSC or GSC proliferation upon feeding of nutrient-restricted flies (Fig. S5).

The role of Hh likely differs in the presence of abundant food. Under normal feeding conditions, Hh signaling is not required for GSC proliferation but is still essential for FSC proliferation control (Forbes et al., 1996a; King et al., 2001; Zhang and Kalderon, 2001). Moreover, boi mutants exhibit excess FSC proliferation even when raised on a normal diet (Hartman et al., 2010). Together, these observations suggest Boi may act as a rheostat under steady-state conditions, translating systemic dietary cholesterol levels to modulate Hh release and FSC proliferation. Defining how Hh is delivered to the FSC niche and processed by FSCs to promote their proliferation will provide insight into the contribution of this mechanism under both refed and steady-state conditions.

Recent work from several laboratories has shown that changes in nutritional status can have dramatic effects on stem cell proliferation, maintenance, and self-renewal. In the cases reported so far, diet-dependent changes in insulin signaling affect stem cells directly (LaFever and Drummond-Barbosa, 2005; Mairet-Coello et al., 2009; Chell and Brand, 2010; McLeod et al., 2010; Michaelson et al., 2010; Sousa-Nunes et al., 2010; O’Brien et al., 2011) or by altering signaling events within components of the stem cell niche or differentiating daughter cells (Hsu and Drummond-Barbosa, 2009a; Mathur et al., 2010; McLeod et al., 2010). Insulin release from producing cells in mammals has mechanistic similarities to nutrient-stimulated Hh release in the fly ovary because insulin is sequestered in vesicles at the surface of producing cells and released when increased local glucose levels promote rapid and efficient secretion (Rutter and Hill, 2006). However, our results demonstrate that the primary nutrient required for feeding-stimulated FSC proliferation is dietary cholesterol. In flies, absorption of dietary cholesterol occurs in the midgut, the equivalent of the mammalian small intestine (Voght et al., 2007). The nuclear hormone receptor DHR96 binds directly to cholesterol (Horner et al., 2009) and maintains cholesterol and triacylglycerol homeostasis through transcriptional regulation of genes involved in lipid metabolism in absorptive cells of the larval midgut (Horner et al., 2009; Sieber and Thummel, 2009, 2012; Bujold et al., 2010). Our results are consistent with a model in which DHR96 also functions within apical cells of the ovary as a sensor of changes in systemic cholesterol levels (Fig. 3). DHR96-mediated cholesterol homeostasis might control membrane composition within apical cells or expression of transcriptional targets that promote S6K activation, resulting in Hh release through phosphorylation of the Boi C terminus.

Initially, it was also possible that some of the effects of diet on Hh-stimulated FSC proliferation might be caused by altered cholesterol modification of the Hh protein. Full-length Hh precursor proteins are cleaved during transit through the Golgi followed by the addition of cholesterol to the newly generated C-terminal ends of active Hh ligand, a mechanism that is known to control Hh diffusion across tissues and liposome-dependent delivery to receiving cells (Porter et al., 1996; Guerrero and Chiang, 2007; Eaton, 2008). However, a form of Hh that cannot be modified by cholesterol (Hh-N–GFP) was sequestered in starved flies and exhibited a time course of release and accumulation in FSCs upon feeding that was nearly identical to that observed for cholesterol-modified Hh (Hh-GFP; Fig. 4). The primary difference between unmodified and cholesterol-modified Hh was in the timing of Hh reaccumulation on the surface of apical cells after a feeding-stimulated release (Fig. 4). Although the role of cholesterol modification in Hh delivery to FSCs has not yet been addressed, these results suggest that the primary role of dietary cholesterol in apical cells is to trigger release of mature, cholesterol-modified Hh molecules sequestered outside of apical cells rather than to modify nascently generated Hh ligand on the inside.

In addition to fly ovarian stem cells, epithelial stem cells in the fly midgut and neuroblasts in developing fly embryos proliferate in response to changes in the nutritional status of the organism via a multistep pathway (Chell and Brand, 2010; Sousa-Nunes et al., 2010; O’Brien et al., 2011). In both cases, systemic signals induce locally produced growth factors to stimulate stem cell proliferation in a paracrine fashion. Proliferation of mammalian neural stem cells also is sensitive to changes in nutritional status (Spéder et al., 2011). These cells proliferate in response to stimulation with Sonic Hh (Traiffort et al., 2010), suggesting the possibility that feeding-triggered Sonic Hh release might be conserved in this tissue. Progenitor cell populations in other nutrient-responsive tissues such as the liver also proliferate in response to Sonic Hh signaling (Sánchez and Fabregat, 2010), but the connection between dietary changes and Hh signaling have not been examined. Finally, this mechanism may contribute to human conditions such as cholesterol metabolism disorders, aging-related decline in tissue function, or cancer initiation and progression, in which Hh signaling and diet may be linked (Longo and Fontana, 2010; Omodei and Fontana, 2011; Porter and Herman, 2011). If conserved in mammalian tissues, our results suggest that some of the benefits of a low calorie diet occur because of reduced levels of growth factor release, resulting in reduced proliferation and extended life span of normal stem cell populations.

Materials and methods

Fly strains

boie01708 (boie) was generated by Exelixis and is maintained by the Harvard stock center. boie is a loss-of-function allele expressing 0.2% of WT, full-length boi transcript in the ovary (Hartman et al., 2010). Ihog was expressed in apical cells by generating female flies of the genotype ihogEP (P{EP}ihogG13202)/+; bab-Gal4/+. UAS-S6KTE and UAS-S6KSTDE (Barcelo and Stewart, 2002) bear mutations in phosphorylation sites known to be important for maintaining an open, active conformation. Specifically, mutation of T398 to glutamic acid (S6KTE) mimics phosphorylation of this residue by target of rapamycin kinase opening the linker domain of S6K for subsequent activation. Similarly, mutation of two phosphorylation sites in the autoinhibition domain of S6K, S418 to aspartic acid and T422 to glutamic acid (S6KSTDE), stabilizes the open conformation and enables kinase activation via additional phosphorylation events (Barcelo and Stewart, 2002). RNAi directed against smo (P{UAS-smoRNAi}2P{UAS-smoRNAi}), hh (P{TRiP.JF01804}attP2), DHR96 (P{TRiP.JF02350}attP2), S6K (P{KK107986}VIE-260B), or InR (P{TRiP.JF01183}attP2 or P{TRiP.JF01482}attP2) was expressed either in apical cells using bab-Gal4 (P{GawB}bab1{Pgal4-2}) or 109-53-Gal4 (P{GawB} 109-53) or in FSCs and their progeny using 109-30-Gal4 (P{GawB}109-30). UAS-DHR96 (EP-DHR96(P{EPgy2}Hr96EY0217) was overexpressed in apical cells using bab-Gal4. Clonally marked FSCs were generated using the MARCM (Mosaic Analysis with a Repressible Cell Marker) system (Lee and Luo, 2001) with 109-30-Gal4 (Gal80 19AFRT Flp122/19AFRT; 109-30-Gal4/UAS-GFP).

Transgenic fly lines

pUASt-boi (UAS-boi) was generated by cloning the full-length boi transcript boi-RB from pOT2-SD07678 (available at GenBank under accession no. AY061833; Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) into pUASt. pUASt-boiΔFN1 was created by site-directed excision of bases corresponding to amino acids 456–598 of Boi (Hartman et al., 2010). In pUASt-boiΔcyto, amino acids 754–997 of Boi were deleted, and in pUASt-boiΔc-term, amino acids 971–997 of Boi were deleted. In pUASt-boiS983A, serine 983 was mutated to alanine. Amino acid numbers are from Boi isoform B (available at RefSeq under accession no. NP_726811). pUASt-Hh-GFP (Hh-GFP) was generated by cloning full-length PCR-amplified Hh into pDONR. pml1-digested EGFP PCR amplified from pTWG (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) was inserted into pml1-digested pDONR-Hh. The pml1 restriction site falls directly before the site where full-length Hh is cleaved and modified by the addition of cholesterol, resulting in a GFP-tagged, cholesterol-modified active Hh molecule (Torroja et al., 2004). pUASt-Hh-N–GFP (Hh-N–GFP) was generated by cloning PCR-amplified Hh-N (amino acids 1–257) into pDONR. Hh-N is an active form of Hh that lacks cholesterol modification. Hh-GFP and Hh-N–GFP were then transferred into pTW and pTWG. All transgenic fly lines were created using the Drosophila cloning system (Gateway; Carnegie Institution of Washington). Transgenic flies were generated by BestGene, Inc.

Nutritional assays

Nutrient restriction was performed as follows: Flies were raised on fruit juice plates containing only simple sugars (50% grape juice, 3% bacto agar, 1% glacial acetic acid, and 1% methyl paraben) and stimulated by feeding with yeast or yeast extract supplemented with 0.2 mg/g cholesterol in EtOH or EtOH only for the indicated times. Egg numbers were counted every 24 h in triplicate. TUNEL assay was performed using in situ apoptosis detection kit (ApopTag red; EMD Millipore).

Antibody generation

Polyclonal anti–FC-NA antibodies were developed from the injection of an antigen consisting of full-length GST fused to three amino acids, A-E-R, into Sprague-Dawley rats. The resulting antiserum marks an unidentified antigen expressed at high levels in all follicle cells, including FSCs, and at much lower levels in other cells within the ovary.

Immunofluorescence

Fly ovaries were prepared as previously described (Hartman et al., 2010). In brief, flies were dissected in Grace’s insect medium (Sigma-Aldrich), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, washed three times for 10 min in PBS-T (PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100), and incubated with primary antibody in PBS-T with 0.5% BSA for 2 h at room temperature. Ovaries were washed three times for 10 min in PBS-T and incubated with secondary antibody in PBS-T with 0.5% BSA for 2 h at room temperature. Ovaries to be stained with Boi antibody were fixed in 2% formaldehyde on ice for 10 min. WT and mutant ovaries were compared directly by dissecting, fixing, and immunostaining with premixed primary and secondary antibodies at the same time. Primary antibodies were rat anti-Boi (1:50), rabbit anti-Vasa (1:2,000; Hay et al., 1990); rabbit anti-Hh (a gift from P. Therond , Institut Valrose Biologie, Nice, France; 1:100; Gallet et al., 2003), goat anti-Hh (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-Fas3 (1:25; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; Patel et al., 1987), mouse anti–Lamin C (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; Riemer et al., 1995), rat anti–FC-NA (1:2,000), chicken anti-GFP (1:1,000; Invitrogen), or rabbit antiphospho–histone-H3 (1:1,000; EMD Millipore). Secondary antibodies used were FITC, Cy3, and Cy5 conjugated to species-specific secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.). Samples were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were collected at room temperature (approximately 22°C) using 40×, 1.25 NA or 63×, 1.4 NA oil immersion lenses (Leica) on an upright microscope (DM5000 B; Leica) coupled to a confocal laser scanner (TCS SP5; Leica). LAS AF SP5 software (Leica) was used for data acquisition. Images representing individual channels of single confocal slices from each germarium were exported as TIFF files, and images were converted to figures using Photoshop software (Adobe).

p70S6K assay

0.2 µg active p70S6K (R&D Systems) was incubated with 800 µM ATP/γ-[32P]ATP in kinase buffer and 3 µg GST, GST-Boi, or GST-Boi983A peptides (amino acids 973–998) at 30°C for 30 min, and reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie blue staining and autoradiography.

Statistics

Dividing FSCs were determined by scoring 215–2,100 germaria for phospho–histone-H3–positive FSCs per germarium. FSCs were identified by their location at the border of germarial regions 2A and 2B, low level expression of Fas3 (Fas3lo), a marker for prefollicle cells, and the presence of a triangular nucleus, a feature that distinguishes FSCs from their daughter cells and neighboring escort cells ((Nystul and Spradling, 2007). Student’s t tests for two samples were used, with significance achieved at P ≤ 0.05. The Bonferroni method was used for feeding experiments in which multiple tests were run on associated data.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows WT flies survive up to 75 d on nutrient-restricted diets. Fig. S2 shows expression patterns of Gal4 drivers in germaria. Fig. S3 shows localization of endogenous Hh in nutrient-deprived and refed WT flies. Fig. S4 shows FSCs can be identified by specific characteristics. Fig. S5 shows loss of InR in apical cells does not block FSC proliferation after refeeding. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201212094/DC1. Additional data are available in the JCB DataViewer at http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201212094.dv.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Okada, G. Rall, J. Peterson, D. Connolly, A. Tulin, L. O’Brien, E.J. Hubbard, H. Gillin, M. Horner, C. Thummel, and D. Wiest for suggestions and help, P. Therond for the anti-Hh antibody, resource centers at Bloomington, Harvard (GM084947), and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development), and the Fox Chase Cancer Center Biostatistics (S. Litwin), Genomics, DNA Sequencing, and Laboratory Animal Facilities.

Grants were obtained from the Fox Chase Cancer Center Board of Associates (T.R. Hartman), the Bucks County Board of Associates (A.M. O’Reilly), the Pennsylvania Department of Health (Health Research Formula Funds; A.M. O’Reilly), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Ben Franklin Technology Development Authority (Keystone Innovation Starter Kit C000026964; A.M. O’Reilly), American Cancer Society (IRG-92-027-16 [A.M. O’Reilly]; PF-11-068-01-TBE [T.I. Strochlic]), and National Institutes of Health (HD065800 [A.M. O’Reilly]; CA06927 [Fox Chase Cancer Center]).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- FC-NA

- follicle cell nuclear antigen

- FSC

- follicle stem cell

- GSC

- germline stem cell

- Hh

- Hedgehog

- InR

- insulin receptor

- S6K

- S6 kinase

- UAS

- upstream activation sequence

- WT

- wild type

References

- Bae G.U., Domené S., Roessler E., Schachter K., Kang J.S., Muenke M., Krauss R.S. 2011. Mutations in CDON, encoding a hedgehog receptor, result in holoprosencephaly and defective interactions with other hedgehog receptors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89:231–240 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo H., Stewart M.J. 2002. Altering Drosophila S6 kinase activity is consistent with a role for S6 kinase in growth. Genesis. 34:83–85 10.1002/gene.10132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachy P.A., Hymowitz S.G., Lazarus R.A., Leahy D.J., Siebold C. 2010. Interactions between Hedgehog proteins and their binding partners come into view. Genes Dev. 24:2001–2012 10.1101/gad.1951710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettoun D.J., Buck D.W., II, Lu J., Khalifa B., Chin W.W., Nagpal S. 2002. A vitamin D receptor-Ser/Thr phosphatase-p70 S6 kinase complex and modulation of its enzymatic activities by the ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24847–24850 10.1074/jbc.C200187200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettoun D.J., Lu J., Khalifa B., Yee Y., Chin W.W., Nagpal S. 2004. Ligand modulates VDR-Ser/Thr protein phosphatase interaction and p70S6 kinase phosphorylation in a cell-context-dependent manner. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89-90:195–198 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujold M., Gopalakrishnan A., Nally E., King-Jones K. 2010. Nuclear receptor DHR96 acts as a sentinel for low cholesterol concentrations in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:793–805 10.1128/MCB.01327-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M., Cooley L. 2000. Eggs to die for: cell death during Drosophila oogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 7:1071–1074 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera G.R., Godt D., Fang P.Y., Couderc J.L., Laski F.A. 2002. Expression pattern of Gal4 enhancer trap insertions into the bric à brac locus generated by P element replacement. Genesis. 34:62–65 10.1002/gene.10115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda T.R., Abplanalp W., Um S.H., Pfluger P.T., Schrott B., Brown K., Grant E., Carnevalli L., Benoit S.C., Morgan D.A., et al. 2012. Metabolic control by S6 kinases depends on dietary lipids. PLoS ONE. 7:e32631 10.1371/journal.pone.0032631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chell J.M., Brand A.H. 2010. Nutrition-responsive glia control exit of neural stem cells from quiescence. Cell. 143:1161–1173 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli V.R., Wang J., Dow J.A. 2007. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39:715–720 10.1038/ng2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole F., Krauss R.S. 2003. Microform holoprosencephaly in mice that lack the Ig superfamily member Cdon. Curr. Biol. 13:411–415 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00088-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond-Barbosa D., Spradling A.C. 2001. Stem cells and their progeny respond to nutritional changes during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 231:265–278 10.1006/dbio.2000.0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton S. 2008. Multiple roles for lipids in the Hedgehog signalling pathway. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:437–445 10.1038/nrm2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotow H., Thomas G. 1992. Substrate recognition determinants of the mitogen-activated 70K S6 kinase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 267:3074–3078 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L., Partridge L., Longo V.D. 2010. Extending healthy life span—from yeast to humans. Science. 328:321–326 10.1126/science.1172539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A.J., Lin H., Ingham P.W., Spradling A.C. 1996a. hedgehog is required for the proliferation and specification of ovarian somatic cells prior to egg chamber formation in Drosophila. Development. 122:1125–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A.J., Spradling A.C., Ingham P.W., Lin H. 1996b. The role of segment polarity genes during early oogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 122:3283–3294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallet A., Rodriguez R., Ruel L., Therond P.P. 2003. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog is required for trafficking and movement, revealing an asymmetric cellular response to hedgehog. Dev. Cell. 4:191–204 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00031-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Géminard C., Rulifson E.J., Léopold P. 2009. Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 10:199–207 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero I., Chiang C. 2007. A conserved mechanism of Hedgehog gradient formation by lipid modifications. Trends Cell Biol. 17:1–5 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Wang Z. 2009. The glypican Dally is required in the niche for the maintenance of germline stem cells and short-range BMP signaling in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 136:3627–3635 10.1242/dev.036939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman T.R., Zinshteyn D., Schofield H.K., Nicolas E., Okada A., O’Reilly A.M. 2010. Drosophila Boi limits Hedgehog levels to suppress follicle stem cell proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 191:943–952 10.1083/jcb.201007142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett C.C. 1948. The utilization of sugars and other substances by Drosophila. Biol. Bull. 95:114–123 10.2307/1538158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay B., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. 1990. Localization of vasa, a component of Drosophila polar granules, in maternal-effect mutants that alter embryonic anteroposterior polarity. Development. 109:425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y., Kobayashi S., Nakato H. 2009. Drosophila glypicans regulate the germline stem cell niche. J. Cell Biol. 187:473–480 10.1083/jcb.200904118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner M.A., Pardee K., Liu S., King-Jones K., Lajoie G., Edwards A., Krause H.M., Thummel C.S. 2009. The Drosophila DHR96 nuclear receptor binds cholesterol and regulates cholesterol homeostasis. Genes Dev. 23:2711–2716 10.1101/gad.1833609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H.-J., Drummond-Barbosa D. 2009a. Insulin levels control female germline stem cell maintenance via the niche in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:1117–1121 10.1073/pnas.0809144106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H.J., Drummond-Barbosa D. 2009b. Insulin levels control female germline stem cell maintenance via the niche in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:1117–1121 10.1073/pnas.0809144106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H.J., Drummond-Barbosa D. 2011. Insulin signals control the competence of the Drosophila female germline stem cell niche to respond to Notch ligands. Dev. Biol. 350:290–300 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H.J., LaFever L., Drummond-Barbosa D. 2008. Diet controls normal and tumorous germline stem cells via insulin-dependent and -independent mechanisms in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 313:700–712 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzi L., Lévesque M., Morin S., Laniel D., Wilkes B.C., Mille F., Krauss R.S., McMahon A.P., Allen B.L., Charron F. 2011. Boc and Gas1 each form distinct Shh receptor complexes with Ptch1 and are required for Shh-mediated cell proliferation. Dev. Cell. 20:788–801 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King F.J., Szakmary A., Cox D.N., Lin H. 2001. Yb modulates the divisions of both germline and somatic stem cells through piwi- and hh-mediated mechanisms in the Drosophila ovary. Mol. Cell. 7:497–508 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00197-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R.C. 1970. Ovarian Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press, New York: 227 pp [Google Scholar]

- King-Jones K., Horner M.A., Lam G., Thummel C.S. 2006. The DHR96 nuclear receptor regulates xenobiotic responses in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 4:37–48 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilly D., Spana E.P., Perrimon N., Padgett R.W., Xie T. 2005. BMP signaling is required for controlling somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila ovary. Dev. Cell. 9:651–662 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König A., Yatsenko A.S., Weiss M., Shcherbata H.R. 2011. Ecdysteroids affect Drosophila ovarian stem cell niche formation and early germline differentiation. EMBO J. 30:1549–1562 10.1038/emboj.2011.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFever L., Drummond-Barbosa D. 2005. Direct control of germline stem cell division and cyst growth by neural insulin in Drosophila. Science. 309:1071–1073 10.1126/science.1111410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T., Luo L. 2001. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 24:251–254 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01791-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist R.A., Ottina K.A., Wheeler D.B., Hsu P.P., Thoreen C.C., Guertin D.A., Ali S.M., Sengupta S., Shaul Y.D., Lamprecht M.R., et al. 2011. Genome-scale RNAi on living-cell microarrays identifies novel regulators of Drosophila melanogaster TORC1-S6K pathway signaling. Genome Res. 21:433–446 10.1101/gr.111492.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Lim T.M., Cai Y. 2010. The Drosophila female germline stem cell lineage acts to spatially restrict DPP function within the niche. Sci. Signal. 3:ra57 10.1126/scisignal.2000740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo V.D., Fontana L. 2010. Calorie restriction and cancer prevention: metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31:89–98 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Onieva L., Fernández-Miñán A., González-Reyes A. 2008. Jak/Stat signalling in niche support cells regulates dpp transcription to control germline stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 135:533–540 10.1242/dev.016121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairet-Coello G., Tury A., DiCicco-Bloom E. 2009. Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes G(1)/S cell cycle progression through bidirectional regulation of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in developing rat cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 29:775–788 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1700-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margadant C., Monsuur H.N., Norman J.C., Sonnenberg A. 2011. Mechanisms of integrin activation and trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23:607–614 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis J., Spradling A. 1995. Identification and behavior of epithelial stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 121:3797–3807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur D., Bost A., Driver I., Ohlstein B. 2010. A transient niche regulates the specification of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. Science. 327:210–213 10.1126/science.1181958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan J.S., Yao S., Zheng X., Geisbrecht B.V., Ghirlando R., Beachy P.A., Leahy D.J. 2006. Structure of a heparin-dependent complex of Hedgehog and Ihog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:17208–17213 10.1073/pnas.0606738103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan J.S., Zheng X., Hauk G., Ghirlando R., Beachy P.A., Leahy D.J. 2008. The mode of Hedgehog binding to Ihog homologues is not conserved across different phyla. Nature. 455:979–983 10.1038/nature07358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod C.J., Wang L., Wong C., Jones D.L. 2010. Stem cell dynamics in response to nutrient availability. Curr. Biol. 20:2100–2105 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson D., Korta D.Z., Capua Y., Hubbard E.J. 2010. Insulin signaling promotes germline proliferation in C. elegans. Development. 137:671–680 10.1242/dev.042523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris L.X., Spradling A.C. 2011. Long-term live imaging provides new insight into stem cell regulation and germline-soma coordination in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 138:2207–2215 10.1242/dev.065508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S.J., Spradling A.C. 2008. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 132:598–611 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman L.P., Fink J.L., Narzinski K., Ramachandran P.V., Hathiramani S.S., Cagan R.L., Baranski T.J. 2011. A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis Model Mech. 4:842–849 10.1242/dmm.007948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystul T., Spradling A. 2007. An epithelial niche in the Drosophila ovary undergoes long-range stem cell replacement. Cell Stem Cell. 1:277–285 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystul T., Spradling A. 2010. Regulation of epithelial stem cell replacement and follicle formation in the Drosophila ovary. Genetics. 184:503–515 10.1534/genetics.109.109538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien L.E., Soliman S.S., Li X., Bilder D. 2011. Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell. 147:603–614 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omodei D., Fontana L. 2011. Calorie restriction and prevention of age-associated chronic disease. FEBS Lett. 585:1537–1542 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly A.M., Lee H.H., Simon M.A. 2008. Integrins control the positioning and proliferation of follicle stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. J. Cell Biol. 182:801–815 10.1083/jcb.200710141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N.H., Snow P.M., Goodman C.S. 1987. Characterization and cloning of fasciclin III: a glycoprotein expressed on a subset of neurons and axon pathways in Drosophila. Cell. 48:975–988 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90706-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter F.D., Herman G.E. 2011. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 52:6–34 10.1194/jlr.R009548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J.A., Young K.E., Beachy P.A. 1996. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog signaling proteins in animal development. Science. 274:255–259 10.1126/science.274.5285.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett T.L., McCall K. 2012. Role of the insulin/Tor signaling network in starvation-induced programmed cell death in Drosophila oogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 19:1069–1079 10.1038/cdd.2011.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett T.L., Tanner E.A., McCall K. 2009. Cracking open cell death in the Drosophila ovary. Apoptosis. 14:969–979 10.1007/s10495-009-0369-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemer D., Stuurman N., Berrios M., Hunter C., Fisher P.A., Weber K. 1995. Expression of Drosophila lamin C is developmentally regulated: analogies with vertebrate A-type lamins. J. Cell Sci. 108:3189–3198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter G.A., Hill E.V. 2006. Insulin vesicle release: walk, kiss, pause … then run. Physiology (Bethesda). 21:189–196 10.1152/physiol.00002.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez A., Fabregat I. 2010. Growth factor- and cytokine-driven pathways governing liver stemness and differentiation. World J. Gastroenterol. 16:5148–5161 10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang J.H. 1956. The quantitative nutritional requirements of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 33:45–72 [Google Scholar]

- Sieber M.H., Thummel C.S. 2009. The DHR96 nuclear receptor controls triacylglycerol homeostasis in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 10:481–490 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber M.H., Thummel C.S. 2012. Coordination of triacylglycerol and cholesterol homeostasis by DHR96 and the Drosophila LipA homolog magro. Cell Metab. 15:122–127 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Xie T. 2003. Wingless signaling regulates the maintenance of ovarian somatic stem cells in Drosophila. Development. 130:3259–3268 10.1242/dev.00524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa-Nunes R., Cheng L.Y., Gould A.P. 2010. Regulating neural proliferation in the Drosophila CNS. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20:50–57 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spéder P., Liu J., Brand A.H. 2011. Nutrient control of neural stem cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23:724–729 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A.C. 1993. Developmental genetics of oogenesis. In The Development of Drosophila Melanogaster. Vol. 1 Michael Bate, Arias Alfonso Martinez, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY: 1–70 [Google Scholar]

- Szakmary A., Reedy M., Qi H., Lin H. 2009. The Yb protein defines a novel organelle and regulates male germline stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 185:613–627 10.1083/jcb.200903034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenzen T., Allen B.L., Cole F., Kang J.S., Krauss R.S., McMahon A.P. 2006. The cell surface membrane proteins Cdo and Boc are components and targets of the Hedgehog signaling pathway and feedback network in mice. Dev. Cell. 10:647–656 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima J., Bownes M. 2005. A microarray analysis of genes involved in relating egg production to nutritional intake in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Death Differ. 12:429–440 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima J., Takaki K., Sakurai S., Bownes M. 2005. Nutritional status affects 20-hydroxyecdysone concentration and progression of oogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Endocrinol. 187:69–79 10.1677/joe.1.06220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torroja C., Gorfinkiel N., Guerrero I. 2004. Patched controls the Hedgehog gradient by endocytosis in a dynamin-dependent manner, but this internalization does not play a major role in signal transduction. Development. 131:2395–2408 10.1242/dev.01102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W. 1947. Insect nutrition. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 22:148–177 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1947.tb00327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traiffort E., Angot E., Ruat M. 2010. Sonic Hedgehog signaling in the mammalian brain. J. Neurochem. 113:576–590 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06642.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vied C., Reilein A., Field N.S., Kalderon D. 2012. Regulation of stem cells by intersecting gradients of long-range niche signals. Dev. Cell. 23:836–848 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voght S.P., Fluegel M.L., Andrews L.A., Pallanck L.J. 2007. Drosophila NPC1b promotes an early step in sterol absorption from the midgut epithelium. Cell Metab. 5:195–205 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]