Abstract

Alkanes are major constituents of crude oil. They are also present at low concentrations in diverse non-contaminated because many living organisms produce them as chemo-attractants or as protecting agents against water loss. Alkane degradation is a widespread phenomenon in nature. The numerous microorganisms, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic, capable of utilizing alkanes as a carbon and energy source, have been isolated and characterized. This review summarizes the current knowledge of how bacteria metabolize alkanes aerobically, with a particular emphasis on the oxidation of long-chain alkanes, including factors that are responsible for chemotaxis to alkanes, transport across cell membrane of alkanes, the regulation of alkane degradation gene and initial oxidation.

Keywords: alkane degradation, hydroxylation, monooxygenase, regulations of gene expression, chemotaxis, transporter, AlmA, LadA

INTRODUCTION

Various microorganisms, including bacteria, filamentous fungi and yeasts, can degrade alkanes (van Beilen et al., 2003; Wentzel et al., 2007; Rojo, 2009). Notably, some recently characterized bacterial species are highly specialized for hydrocarbon degradation. These species are called hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria (HCB), and they play a key role in the removal of hydrocarbons from polluted and non-polluted environments (Harayama et al., 2004; Head et al., 2006; Yakimov et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010a,b).

Of particular importance is Alcanivorax, a marine bacterium that can assimilate various linear or branched alkanes but that is unable to metabolize aromatic hydrocarbons, sugars, amino acids, and most other common carbon sources (Liu and Shao, 2005; Yakimov et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008). Alcanivorax bacteria are present in non-polluted seawater in low numbers; however, the number of Alcanivorax can increase as a result of an oil spill, and they are believed to play an important role in the natural bioremediation of oil spills worldwide (Kasai et al., 2002; Hara et al., 2003; Harayama et al., 2004; McKew et al., 2007a,b; Yakimov et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010a,b).

More recently, other HCBs belonging to the genera Thalassolituus (Yakimov et al., 2004), Oleiphilus (Golyshin et al., 2002), Oleispira (Yakimov et al., 2003), Marinobacter (Duran, 2010), Bacillus and Geobacillus (Marchant et al., 2006; Meintanis et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006) have also been shown to play an important role in the degradation of oil spills in marine environments (Coulon et al., 2007; McKew et al., 2007a,b; Hazen et al., 2010).

Several reviews have covered different aspects of the physiology, enzymes and pathways that are responsible for alkane degradation (van Beilen et al., 2003; van Hamme et al., 2003; Coon, 2005; van Beilen and Funhoff, 2007; Wentzel et al., 2007; Rojo, 2009; Austin and Groves, 2011). This review focuses on recent advances in alkane chemotaxis, across membrane transport and gene regulations. In addition, newly discovered enzymes that are responsible for long-chain alkane mineralization are also discussed.

CHEMOTAXIS TO LINEAR ALKANES

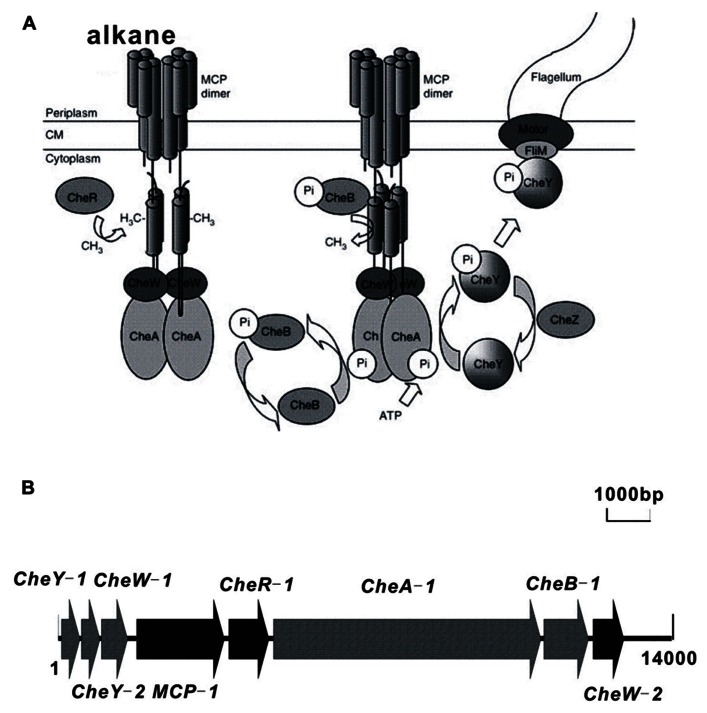

Chemotaxis facilitates the movement of microorganisms toward or away from chemical gradients in the environment, and this process plays a role in biodegradation by bringing cells into contact with degradation substrates (Parales and Harwood, 2002; Parales et al., 2008). Alkanes are sources of carbon and energy for many bacterial species and have been shown to function as chemo-attractants for certain microorganisms. A bacterial Flavimonas oryzihabitans isolate that was obtained from soil contaminated with gas oil was shown to be chemotactic to gas oil and hexadecane (Lanfranconi et al., 2003). Similarly, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 is chemotactic to hexadecane (Smits et al., 2003). The tlpS gene, which is located downstream of the alkane hydroxylase gene alkB1 in the PAO1 genome, is predicted to encode membrane-bound methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCP) that may play a role in alkane chemotaxis (Smits et al., 2003), although no experimental evidence exists. Similarly, the gene alkN is predicted to encode an MCP that could be involved in alkane chemotaxis in P. putida GPo1 (van Beilen et al., 2001). Our recent investigation of the genome sequence of Alcanivorax dieselolei B-5 (Lai et al., 2012) identified the alkane chemotaxis machinery of Alcanivorax, which consists of eight cytoplasmic chemotaxis proteins that transmit signals from the MCP proteins to the flagellar motors (Figure 1). This chemotaxis machinery is similar to that of Escherichia coli (Parales and Ditty, 2010). However, further investigation is necessary to confirm the mechanism of alkane chemotaxis in A. dieselolei B-5.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of the chemosensory signaling system of A. dieselolei B-5. (A) MCP dimers with associated CheW and CheA proteins are shown in the presence (left) and absence of alkane (right). Cells responding to a gradient of attractant will sense the attractant bound to the periplasmic side of the cognate MCP and will continue swimming in the favorable direction due to the inability of CheA to autophosphorylate. In the absence of CheA-P, CheY remains in the inactive unphosphorylated state, and swimming behavior remains unchanged. Cells swimming down a gradient of attractant will sense the decrease in attractant concentration due to decreased occupancy of the MCPs. Under these conditions, the MCPs undergo a conformational change that is transmitted across the cytoplasmic membrane and stimulates CheA kinase activity. CheA-P phosphorylates CheY, which in its phosphorylated state binds to the FliM protein in the flagellar motor and causes a change in the direction of flagellar rotation allowing the cell to randomly reorient and swim off in a new direction. Dephosphorylation of CheY-P is accelerated by the CheZ phosphatase. Under all conditions, the constitutive methyltransferase CheR methylates specific glutamyl residues on the cytoplasmic side of the MCP. Methylated MCPs stimulate CheA autophosphorylation, thus resetting the system such that further increases in attractant concentration can be detected. The methylesterase, CheB, becomes active when it is phosphorylated by CheA-P. CheB-P competes with CheR and removes methyl groups from the MCPs. CM, cytoplasmic membrane. (B) Organization of chemotaxis genes involved in alkane metabolism in A. dieselolei B-5. The detailed information of the ORFs of MCP gene cluster is presented. MCP, methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein; CheY-1, CheY-like receiver protein; CheY-2, CheY-like receiver protein; CheW-1, CheW-like protein, signal transduction protein; CheW-2, Chemotaxis protein, signal transduction protein; CheA, CheA signal transduction histidine kinase; CheB, CheB methylesterase; CheR, CheR methyltransferase.

n-ALKANE UPTAKE IN BACTERIA

Although the genes and proteins that enable the passage of aromatic hydrocarbons across the bacterial outer membrane have been identified (van den Berg, 2005; Mooney et al., 2006; Hearn et al., 2008, 2009), the active transport mechanisms involved in alkane uptake remain unclear. Previous reviews(Rojo, 2009) discussed the observation that direct uptake of alkane molecules from the water phase is only possible for low molecular weight alkanes, which are sufficiently soluble to facilitate efficient transport into cells. For medium- and long-chain n-alkanes, microorganisms may gain access to these compounds by adhering to hydrocarbon droplets (which is facilitated by the hydrophobic cell surface) or by surfactant-facilitated access, as reviewed by Rojo (2009). Surfactants have been reported to increase the uptake and assimilation of alkanes, such as hexadecane, in liquid culture (Beal and Betts, 2000; Noordman and Janssen, 2002), but their exact role in alkane uptake is not fully understood. Bacteria that are capable of oil degradation usually produce and secrete surfactants of diverse chemical nature that allow alkane emulsification (Yakimov et al., 1998; Peng et al., 2007, 2008; Qiao and Shao, 2010; Shao, 2010). Based on our understanding of biosurfactant structure and the mechanism of outer membrane transport, we speculate that biosurfactants may be excluded from entering the cell and remain in the extracellular milieu.

In P. putida, alkL in the alk operon is postulated to play an important role in alkane transport into the cell (van Beilen et al., 2004; Hearn et al., 2009). Transcriptome analysis of A. borkumensis Sk2 revealed that the alkane-induced gene blc, encoding the outer membrane lipoprotein Blc, might be involved in alkane uptake because it contains a so-called lipocalin domain (Sabirova et al., 2011). When this domain contacts organic solvents, a small hydrophobic pocket forms and catalyzes the transport of small hydrophobic molecules. More recently, our genome analysis (Lai et al., 2012) and closer examination of A. dieselolei B-5indicated that three outer membrane proteins that belong to the long-chain fatty acid transporter protein (FadL) family are involved in alkane transport (unpublished). The FadL homologs are present in many bacteria that are involved in the biodegradation of xenobiotics (van den Berg, 2005), which are usually hydrophobic and probably enter cells by a mechanism similar to that employed for long-chain (LC) fatty acids by FadL in E. coli.

DEGRADATION PATHWAYS OF n-ALKANES

The initial terminal hydroxylation of n-alkanes can be carried out by enzymes that belong to different families. Microorganisms degrading short-chain length alkanes (C2–C4, where the subindex indicates the number of carbon atoms of the alkane molecule) have enzymes related to methane monooxygenases (van Beilen and Funhoff, 2007). Strains degrading medium-chain length alkanes (C5–C17) frequently contain soluble cytochrome P450s and integral membrane non-heme iron monooxygenases, such as AlkB (Rojo, 2009; Austin and Groves, 2011).

Interestingly, alkane hydroxylases of long-chain length (LC-) alkanes (>C18) are unrelated to the above alkane hydroxylases as characterized recently. One such hydroxylase, AlmA, is an LC-alkane monooxygenase from Acinetobacter. A second hydroxylase is LadA, which is a thermophilic soluble LC-alkane monooxygenase from Geobacillus (Feng et al., 2007; Throne-Holst et al., 2007; Wentzel et al., 2007).

The almA gene, which encodes a putative monooxygenase belonging to the flavin-binding family, was identified from Acinetobacter sp. DSM 17874 (Throne-Holst et al., 2007; Wentzel et al., 2007). This gene encodes the first experimentally confirmed enzyme that is involved in the metabolism of LC n-alkanes of C32 and longer. We provided the first evidence that the AlmA of the genus Alcanivorax functions as an LC-alkane hydroxylase, and found that the gene almA in both A. hongdengensis A-11-3 and A. dieselolei B-5 strains expressed at high levels to facilitate the efficient degradation of LC n-alkanes (Liu et al., 2011; Wang and Shao, 2012a). The almA gene sequences were present in several bacterial genera capable of LC n-alkane degradation, including Alcanivorax, Marinobacter, Acinetobacter, and Parvibaculum (Wang and Shao, 2012b). In addition, similar genes are found in other genera in GenBank, such as Oceanobacter sp. RED65, Ralstonia spp., Mycobacterium spp., Photorhabdus sp., Psychrobacter spp., and Nocardia farcinica IFM10152. However, few of these genes have been functionally characterized.

A unique LC-alkane hydroxylase from the thermophilic bacterium Geobacillus thermodenitrificans NG80-2 has been characterized. This enzyme is called LadA and oxidizes C15–C36 alkanes, generating the corresponding primary alcohols (Feng et al., 2007). The LadA crystal structure has been identified, revealing that LadA belongs to the bacterial luciferase family, which is two-component, flavin-dependent oxygenase (Li et al., 2008). LadA is believed to oxidize alkanes by a mechanism similar to that of other flavoprotein monooxygenases, and its ability to recognize and hydroxylate LC-alkanes most likely results from the way in which it captures the alkane(Li et al., 2008). Therefore, the hydroxylases involved in LC-alkane degradation appear to have evolved specifically, which is in contrast with other alkane monooxygenases such as AlkB and P450.

Interestingly, branched-chain alkanes are thought to be more difficult to degrade than linear alkanes (Pirnik et al., 1974). However, Alcanivorax bacteria efficiently degrade branched alkanes (Hara et al., 2003). In A. borkumensis SK2, isoprenoid hydrocarbon (phytane) strongly induces P450 (a) and alkB2 (Schneiker et al., 2006). In a previous report, we found that both pristane and phytane activate the expression of alkB1 and almA in A. dieselolei B-5 (Liu et al., 2011). In A. hongdengensis A-11-3, we recently found that pristane selectively activates the expression of alkB1, P450-3 and almA (Wang and Shao, 2012a). However, the metabolic pathways that mediate this activity are poorly understood, although they may involve the ω- or β-oxidation of the hydrocarbon molecule (Watkinson and Morgan, 1990).

REGULATION OF ALKANE-DEGRADATION PATHWAYS

The expression of the bacterial genes involved in alkane assimilation is tightly regulated. Alkane-responsive regulators ensure that alkane degradation genes are induced only in the presence of the appropriate hydrocarbons. Many microorganisms(Rojo, 2009; Austin and Groves, 2011) contain several sets of alkane degradation systems, each one being active on a particular kind of alkane or being expressed under specific physiological conditions. In these cases, the regulatory mechanisms should assure an appropriate differential expression of each set of enzymes. The regulators that have been characterized belong to different families, including LuxR/MalT, AraC/XylS, and other non-related families (Table 1).

Table 1.

Transcriptional regulators known or presumed to control the expression of alkane degradation pathways.

| Bacterium | Gene | Family | Effector | Evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. putida GPo1 | alkS | LuxR/MalT | C6–C10 n-alkanes | Direct | Sticher et al. (1997) and Panke et al. (1999) |

| P. putida P1 | alkS | LuxR/MalT | Not tested | Similarity | van Beilen et al. (2001) |

| A. borkumensis SK2 | alkS | LuxR/MalT | Not tested | Similarity | Schneiker et al. (2006) |

| A. borkumensis SK2 | gntR | GntR | Not tested | No | Schneiker et al. (2006) |

| A. borkumensis SK2 | araC | AraC/XylS | Not tested | No | Schneiker et al. (2006) |

| A. borkumensis AP1 | alkS | LuxR/MalT | Not tested | Similarity | van Beilen et al. (2004) |

| A.hongdengensis A-11-3 | tetR | TetR | Not tested | Similarity | Wang and Shao (2012a) |

| A.hongdengensis A-11-3 | gntR | GntR | Not tested | Similarity | Wang and Shao (2012a) |

| A.hongdengensis A-11-3 | araC1 | AraC/XylS | Not tested | Similarity | Wang and Shao (2012a) |

| A.hongdengensis A-11-3 | araC2 | AraC/XylS | Not tested | Similarity | Wang and Shao (2012a) |

| A. dieselolei B-5 | merR | MerR | C14–C26 n-alkanols | Similarity | Liu et al., (2011) |

| A. dieselolei B-5 | araC1 | AraC/XylS | C12–C26 n-alkanols | Similarity | Liu et al., (2011) |

| A. dieselolei B-5 | araC2 | AraC/XylS | C8–C16 n-alkanols | Similarity | Liu et al., (2011) |

| P. butanovora | bmoR | δ54-Dependent | C2–C8 n-alkanols | Direct | Kurth et al. (2008) |

| P. aeruginosa RR1 | gntR | GntR | C10-C20 n-alkanols | Indirect | Marιn et al. (2003) |

| Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 | alkR | AraC/XylS | C7-C18 n-alkanols | Direct | Ratajczak et al. (1998) |

| Acinetobacter sp. M1 | alkRa | AraC/XylS | >C22 n-alkanols | Indirect | Tani et al. (2001) |

| Acinetobacter sp. M1 | alkRb | OruR | C16–C22 n-alkanols | Indirect | Tani et al. (2001) |

REGULATION OF THE ALKANE DEGRADATION PATHWAY IN Pseudomonas spp.

Pseudomonas butanovora species oxidize C2–C8 n-alkanes into the corresponding alcohols with an alkane monooxygenase termed butane monooxygenase (BMO). BMO is a multimeric protein that is formed by the products of the bmoXYBZDC operon (Sluis et al., 2002). The expression of the genes encoding BMO is activated by BmoR, a δ54-dependent transcriptional regulator that recognizes alcohols and aldehydes derived from the C2–C8 n-alkanes that are substrates of BMO, although BmoR does not recognize the alkanes themselves (Kurth et al., 2008).

In P. putida GPo1, the OCT plasmid encodes all of the genes required for the assimilation of C3–C13 alkanes (van Beilen et al., 1994, 2005; Johnson and Hyman, 2006). The genes in this pathway are grouped into two clusters, alkBFGHJKL and alkST (van Beilen et al., 1994, 2001). The alkBFGHJKL operon is transcribed from a promoter named PalkB, whose expression requires the transcriptional activator AlkS and the presence of alkanes (Kok et al., 1989; Panke et al., 1999). An AlkS-dependent reporter system based on a PalkB-luxAB fusion showed that C5–C10 alkanes are efficient activators of the AlkS regulator (Sticher et al., 1997). When alkanes become available, AlkS binds and represses PalkS1 more efficiently than it does in the absence of alkanes. From this binding site, AlkS activates the PalkS2 promoter, resulting in high expression of the alkST genes (Canosa et al., 2000). Therefore, this pathway is controlled by a positive feedback mechanism that is driven by AlkS.

REGULATION OF THE ALKANE DEGRADATION PATHWAY IN Alcanivorax spp.

A gene similar to alkS in P. putida GPo1 is located upstream of alkB1 in A. borkumensis SK2, and AlkS is predicted to be an alkane-responsive transcriptional activator. The expression level of AlkS in strain SK2 cells grown in hexadecane is higher than that of pyruvate-grown cells (Sabirova et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that in A. borkumensis, AlkS activates the expression of alkB1, a gene that encodes an alkane hydroxylase, in response to alkanes. However, it is unlikely that AlkS regulates the expression of alkB2, despite the induction of this gene in response to alkanes (van Beilen et al., 2004). Interestingly, a gene encoding a transcriptional regulator belonging to the GntR family is located immediately upstream of alkB2; however, its role in alkB2 expression has not been reported. A. borkumensis has three genes encoding cytochrome P450 of the CYP153 family (Schneiker et al., 2006). A gene encoding a transcriptional regulator belonging to the AraC family is located close to P450-1, but its role in regulating the P450-1 gene cluster has not been investigated (Schneiker et al., 2006).

In A. hongdengensis, a gene downstream of alkB1 encodes a protein that is similar to TetR family transcriptional regulators (Wang and Shao, 2012a). In addition, a gene encoding a transcriptional regulator belonging to the GntR family is located just upstream of alkB2, although its role in the regulation of alkB2 is not known (Wang and Shao, 2012a). Genes encoding transcriptional regulators belonging to the AraC family are located near P450-1 and P450-2 (Wang and Shao, 2012a). Similar to many of the genes described above, their role in the regulation of the corresponding P450 genes requires further investigation.

Three regulators that are involved in alkane degradation were identified in the A. dieselolei strain B-5 genome sequence, and they belong to different MerR and AraC families (Table 1). Regulatory genes are located upstream of alkB1 and P450, and the proteins encoded by these genes are 46 and 64% similar to MerR and AraC from P. aeruginosa and A. borkumensis SK2, respectively (Liu et al., 2011). Downstream of alkB2, there is a gene encoding a transcriptional regulator that shares 61% similarity with AraC from Marinobacter sp. ELB17 (Liu et al., 2011). Therefore, Alcanivorax strains usually encode multiple alkane hydroxylases that are expressed under the control of different regulators encoded in the same gene cluster as the monooxygenase gene. Our lab is using strain B-5 as a model system to study how cells modulate the expression of these genes in response to different alkanes with varied chain lengths.

GLOBAL REGULATION OF THE ALKANE DEGRADATION PATHWAY

The expression of alkane degradation pathway genes is often down regulated by complex global regulatory controls that ensure that the genes are expressed only under the appropriate physiological conditions or in the absence of any preferred compounds (Rojo, 2009). Two global regulatory networks exist. One network relies on the global regulatory protein Crc (Yuste and Rojo, 2001), while the other network receives information from cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase (Cyo), which is a component of the electron transport chain (Dinamarca et al., 2002, 2003).

The Crc is an RNA-binding protein that interacts with the 5′ end of the alkS mRNA, inhibiting translation (Moreno et al., 2007). A recent study further showed that Crc inhibits the induction of the alkane degradation pathway by limiting not only the translation of their transcriptional activators but also that of genes involved in the entire alkane degradation pathway in P. putida (Hernández-Arranz et al., 2013). In addition, results of this study suggests that Crc follows a multi-step strategy in many cases, targeting uptake, transcription regulation, and/or the production of the associated pathways’ catabolic enzymes (Hernández-Arranz et al., 2013).

However, when cells grow in a minimal salt medium containing succinate as the carbon source, the activity of Crc is low; instead, Cyo terminal oxidase play a key role in the global control that inhibits the induction of the alkane degradation genes (Yuste and Rojo, 2001; Dinamarca et al., 2003). Cyo is one of the five terminal oxidases that have been characterized in P. putida. Inactivation of the Cyo terminal oxidase partially relieves the repression exerted on the alkane degradation pathway under several conditions, while inactivation of any of the other four terminal oxidases does not (Dinamarca et al., 2002; Morales et al., 2006). Cyo affects the expression of many other genes, and this enzyme has been proposed to be a component of a global regulatory network that transmits information regarding the activity of the electron transport chain to coordinate respiration and carbon metabolism (Petruschka et al., 2001; Morales et al., 2006). The expression of the cyo genes encoding the subunits of Cyo terminal oxidase varies depending on oxygen levels and carbon source, and there is a clear correlation between Cyo levels and the extent of alkane degradation pathway repression (Dinamarca et al., 2003).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Research in the last few years has resulted in many new insights into the mechanism of alkane degradation by microorganisms, including the upstream regulations and the long-chain length alkane oxidation. Investigations using “omics” strategies will help us to better understand the global metabolic networks within a microbial cell and the overall process of bacterial alkane-dependent chemotaxis, alkane transport, gene expression regulation and complete mineralization.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Public Welfare Project of SOA(201005032), COMRA project (DY125-15-R-01), National Science Foundation of China (41106151,41176154), International Sci and Tech Cooperation Program of China (2010DFB23320) and the Project sponsored by the Scientific Research Foundation of Third Institute of Oceanography, SOA (2011036).

REFERENCES

- Austin R. N., Groves J. T. (2011). Alkane-oxidizing metalloenzymes in the carbon cycle. Metallomics 3 775–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal R., Betts W. B. (2000). Role of rhamnolipid biosurfactants in the uptake and mineralization of hexadecane in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89 158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canosa I., Sa’nchez-Romero J. M., Yuste L., Rojo F. (2000). A positive feedback mechanism controls expression of AlkS, the transcriptional regulator of the Pseudomonas oleovorans alkane degradation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35 791–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon M. J. (2005). Omega oxygenases: nonheme-iron enzymes and P450 cytochromes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338 378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon F., McKew B. A., Osborn A. M., McGenity T. J., Timmis K. N. (2007). Effects of temperature and biostimulation on oil-degrading microbial communities in temperate estuarine waters. Environ. Microbiol. 9 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinamarca M. A., Aranda-Olmedo I., Puyet A., Rojo F. (2003). Expression of the Pseudomonas putida OCT plasmid alkane degradation pathway is modulated by two different global control signals: evidence from continuous cultures. J. Bacteriol. 185 4772–4778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinamarca M. A., Ruiz-Manzano A., Rojo F. (2002). Inactivation of cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase relieves catabolic repression of the Pseudomonas putida GPo1 alkane degradation pathway. J. Bacteriol. 184 3785–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran R. (2010). “Marinobacter,” in Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology eds McGenity T., van der Meer J. R., de Lorenzo V., Timmis K. N. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ) 1725–1735 [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Wang W., Cheng J., Ren Y., Zhao G., Gao C., et al. (2007). Genome and proteome of long-chain alkane degrading Geobacillus thermodenitrificans NG80-2 isolated from a deep-subsurface oil reservoir. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 5602–5607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golyshin P. N., Chernikova T. N., Abraham W. R., Lunsdorf H., Timmis K. N., Yakimov M. M. (2002). Oleiphilaceae fam. nov., to include Oleiphilus messinensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel marine bacterium that obligately utilizes hydrocarbons. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52 901–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara A., Syutsubo K., Harayama S. (2003). Alcanivorax which prevails in oil-contaminated seawater exhibits broad substrate specificity for alkane degradation. Environ. Microbiol. 5 746–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harayama S., Kasai Y., Hara A. (2004). Microbial communities in oil-contaminated seawater. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen T. C., Dubinsky E. A., DeSantis T. Z., Andersen G. L., Piceno Y. M, Singh N., et al. (2010). Deep-sea oil plume enriches indigenous oil-degrading bacteria. Science 330 204–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head I. M., Jones D. M., Roling W. F. (2006). Marine microorganisms make a meal of oil. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4 173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn E. M., Patel D. R., van den Berg B. (2008). Outer-membrane transport of aromatic hydrocarbons as a first step in biodegradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 8601–8606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn E. M., Patel D. R., Lepore B. W., Indic M, van den Berg B. (2009). Transmembrane passage of hydrophobic compounds through a protein channel wall. Nature 458 367–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Arranz S., Moreno R., Rojo F. (2013). The translational repressor Crc controls the Pseudomonas putida benzoate and alkane catabolic pathways using a multi-tier regulation strategy. Environ. Microbiol. 15 227–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. L., Hyman M. R. (2006). Propane and n-butane oxidation by Pseudomonas putida GPo1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 950–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai Y., Kishira H., Sasaki T., Syutsubo K., Watanabe K., Harayama S. (2002). Predominant growth of Alcanivorax strains in oil-contaminated and nutrient-supplemented sea water. Environ. Microbiol. 4 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok M., Oldenhuis R., van der Linden M. P., Raatjes P., Kingma J., van Lelyveld P. H., et al. (1989). The Pseudomonas oleovorans alkane hydroxylase gene. Sequence and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 264 5435–5441 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth E. G., Doughty D. M., Bottomley P. J., Arp D. J., Sayavedra-Soto L. A. (2008). Involvement of BmoR and BmoG in n-alkane metabolism in “Pseudomonas butanovora.” Microbiology 154 139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranconi M. P., Alvarez H. M., Studdert C. A. (2003). A strain isolated from gas oil-contaminated soil displays chemotaxis towards gas oil and hexadecane. Environ. Microbiol. 5 1002–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Q., Li W., Shao Z. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Alcanivorax dieselolei type strain B5. J. Bacteriol. 194 6674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Liu X., Yang W., Xu F., Wang W., Feng L., et al. (2008). Crystal structure of long-chain alkane monooxygenase (LadA) in complex with coenzyme FMN: unveiling the long-chain alkane hydroxylase. J. Mol. Biol. 376 453–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Shao Z. (2005). Alcanivorax dieselolei sp. nov., a novel alkane-degrading bacterium isolated from sea water and deep-sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55 1181–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wang W., Wu Y., Zhou Z., Lai Q., Shao Z. (2011). Multiple alkane hydroxylase systems in a marine alkane degrader, Alcanivorax dieselolei B-5. Environ. Microbiol. 13 1168–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant R., Sharkey F. H., Banat I. M., Rahman T. J., Perfumo A. (2006). The degradation of n-hexadecane in soil by thermophilic geobacilli. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 56 44–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marιn M. M., Yuste L., Rojo F. (2003). Differential expression of the components of the two alkane hydroxylases from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185 3232–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKew B. A., Coulon F., Osborn A. M., Timmis K. N., McGenity T. J. (2007a). Determining the identity and roles of oil-metabolizing marine bacteria from the Thames estuary, UK. Environ. Microbiol. 9 165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKew B. A., Coulon F., Yakimov M. M., Denaro R., Genovese M., Smith C. J., et al. (2007b). Efficacy of intervention strategies for bioremediation of crude oil in marine systems and effects on indigenous hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 9 1562–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meintanis C., Chalkou K. I., Kormas K. A., Karagouni A. D. (2006). Biodegradation of crude oil by thermophilic bacteria isolated from a volcano island. Biodegradation 17 105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney A., O’Leary N. D., Dobson A. D. (2006). Cloning and functional characterization of the styE gene, involved in styrene transport in Pseudomonas putida CA-3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 1302–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales G., Ugidos A., Rojo F. (2006). Inactivation of the Pseudomonas putida cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase leads to a significant change in the transcriptome and to increased expression of the CIO and cbb3-1 terminal oxidases. Environ. Microbiol. 8 1764–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno R., Ruiz-Manzano A., Yuste L., Rojo F. (2007). The Pseudomonas putida Crc global regulator is an RNA binding protein that inhibits translation of the AlkS transcriptional regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 64 665–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordman W. H., Janssen D. B. (2002). Rhamnolipid stimulates uptake of hydrophobic compounds by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68 4502–4508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panke S., Meyer A., Huber C. M., Witholt B., Wubbolts M. G. (1999). Analkane-responsive expression system for the production of fine chemicals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 2324–2332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parales R. E., Ditty J. L. (2010). “Chemotaxis,” in Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology eds McGenity T., van der Meer J. R., de Lorenzo V., Timmis K. N. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag) 1532–1540 [Google Scholar]

- Parales R. E., Harwood C. S. (2002). Bacterial chemotaxis to pollutants and plant-derived aromatic molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5 266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parales R. E., Ju K.-S., Rollefson J., Ditty J. L. (2008). “Bioavailability, transport and chemotaxis of organic pollutants,” in Microbial Bioremediation. ed Diaz E. (Norfolk: Caister Academic Press) 145–187 [Google Scholar]

- Peng F., Liu Z., Wang L., Shao Z. (2007). An oil-degrading bacterium: Rhodococcus erythropolis strain 3C-9 and its biosurfactants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102 1603–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng F., Wang Y., Sun F., Liu Z., Lai Q., Shao Z. (2008). A novel lipopeptide produced by a Pacific Ocean deep-sea bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. TW53. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105 698–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruschka L., Burchhardt G., Müller C., Weihe C., Herrmann H. (2001). The cyo operon of Pseudomonas putida is involved in catabolic repression of phenol degradation. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirnik M. P., Atlas R. M., Bartha R. (1974). Hydrocarbon metabolism by Brevibacterium erythrogenes: normal and branched alkanes. J. Bacteriol. 119 868–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao N., Shao Z. (2010). Isolation and characterization of a novel biosurfactant produced by hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium Alcanivorax dieselolei B-5. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108 1207–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak A., Geissdorfer W., Hillen W. (1998). Expression of alkane hydroxylase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 is induced by a broad range of n-alkanes and requires the transcriptional activator AlkR. J. Bacteriol. 180 5822–5827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo F. (2009). Degradation of alkanes by bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 11 2477–2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirova J. S., Becker A., Lünsdorf H., Nicaud J., Timmis K. N., Golyshin P. N. (2011). Transcriptional profiling of the marine oil-degrading bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis during growth on n-alkanes. 319 160–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirova J. S., Ferrer M., Regenhardt D., Timmis K. N., Golyshin P. N. (2006). Proteomic insights into metabolic adaptations in Alcanivorax borkumensis induced by alkane utilization. J. Bacteriol. 188 3763–3773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiker S., Martins dos Santos V. A., Bartels D., Bekel T., Brecht M., Buhrmester J., et al. (2006). Genome sequence of the ubiquitous hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 24 997–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z. (2010). “Trehalolipids,” in Biosurfactant: from Genes to Application ed Soberon-Chavez G. (Berlin: Springer) 121–144 [Google Scholar]

- Sluis M. K., Sayavedra-Soto L. A., Arp D. J. (2002). Molecular analysis of the soluble butane monooxygenase from “Pseudomonas butanovora.” Microbiology 148 3617–3629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits T. H., Witholt B, van Beilen J. B. (2003). Functional characterization of genes involved in alkane oxidation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 84 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sticher P., Jaspers M. C., Stemmler K., Harms H., Zehnder A. J, van der Meer J. R. (1997). Development and characterization of a whole-cell bioluminescent sensor for bioavailable middle-chain alkanes in contaminated groundwater samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 4053–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani A., Ishige T., Sakai Y., Kato N. (2001). Gene structures and regulation of the alkane hydroxylase complex in Acinetobacter sp. strain M-1. J. Bacteriol. 183 1819–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throne-Holst M., Wentzel A., Ellingsen T., Kotlar H., Zotchev S. (2007). Identification of novel genes involved in long-chain nalkane degradation by Acinetobacter sp. strain DSM 17874. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73 3327–3332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beilen J. B., Funhoff E. G. (2007). Alkane hydroxylases involved in microbial alkane degradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74 13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beilen J. B., Holtackers R., Luscher D., Bauer U., Witholt B., Duetz W. A. (2005). Biocatalytic production of perillyl alcohol from limonene by using a novel Mycobacterium sp. cytochrome P450 alkane hydroxylase expressed in Pseudomonas putida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 1737–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beilen J. B., Li Z., Duetz W. A., Smits T. H. M., Witholt B. (2003). Diversity of alkane hydroxylase systems in the environment. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 58 427–440 [Google Scholar]

- van Beilen J. B., Marin M. M., Smits T. H., Rothlisberger M., Franchini A. G., Witholt B., et al. (2004). Characterization of two alkane hydroxylase genes from the marine hydrocarbonoclastic bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Environ. Microbiol. 6 264–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beilen J. B., Panke S., Lucchini S., Franchini A. G., Röthlisberger M., Witholt B. (2001). Analysis of Pseudomonas putida alkane degradation gene clusters and flanking insertion sequences: evolution and regulation of the alk-genes. Microbiology 147 1621–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beilen J. B., Wubbolts M. G., Witholt B. (1994). Genetics of alkane oxidation by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Biodegradation 5 161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg B. (2005). The FadL family: unusual transporters for unusual substrates. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15 401–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hamme J. D., Singh A., Ward O. P. (2003). Recent advances in petroleum microbiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67 503–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Tang Y., Wang S., Liu R. L., Liu M. Z., Zhang Y., et al. (2006). Isolation and characterization of a novel thermophilic Bacillus strain degrading long-chain n-alkanes. Extremophiles 10 347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang W., Shao Z. (2010a). Gene diversity of CYP153A and AlkB alkane hydroxylases in oil-degrading bacteria isolated from the Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 12 1230–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Wang L., Shao Z. (2010b). Diversity and abundance of oil-degrading bacteria and alkane hydroxylase (alkB) genes in the subtropical seawater of Xiamen Island. Microb. Ecol. 60 429–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Shao Z. (2012a). Diversity of flavin-binding monooxygenase genes (almA) in marine bacteria capable of degradation long-chain alkanes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 80 523–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Shao Z. (2012b). Genes involved in alkane degradation in the Alcanivorax hongdengensis strain A-11-3. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 94 437–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkinson R. J., Morgan P. (1990). Physiology of aliphatic hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms. Biodegradation 1 79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel A., Ellingsen T. E., Kotlar H. K., Zotchev S. B., Throne-Holst M. (2007). Bacterial metabolism of long chain n-alkanes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76 1209–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Lai Q., Zhou Z., Qiao N., Liu C., Shao Z. (2008). Alcanivorax hongdengensis sp. nov., a alkane-degrading bacterium isolated from surface seawater of the straits of Malacca and Singapore, producing a lipopeptide as its biosurfactant. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59 1474–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M., Giuliano L., Denaro R., Crisafi E., Chernikova T. N., Abraham W. R., et al. (2004). Thalassolituus oleivorans general nov.,sp. nov., a novel marine bacterium that obligately utilizes hydrocarbons. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54 141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M., Giuliano L., Gentile G., Crisafi E., Chernikova T. N., Abraham W. R., et al. (2003). Oleispira antarctica gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel hydrocarbonoclastic marine bacterium isolated from Antarctic coastal sea water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53 779–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M., Golyshin P. N., Lang S., Moore E. R., Abraham W. R., Lunsdorf H., et al. (1998). Alcanivorax borkumensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, hydrocarbon-degrading and surfactant-producing marine bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48 339–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M., Timmis K. N., Golyshin P. N. (2007). Obligate oil-degrading marine bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste L., Rojo F. (2001). Role of the crc gene in catabolic repression of the Pseudomonas putida GPo1 alkane degradation pathway. J. Bacteriol. 183 6197–6206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]