Abstract

We found previously that the Chlamydomonas HSP70A promoter counteracts transcriptional silencing of downstream promoters in a transgene setting. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms, we analyzed chromatin state and transgene expression in transformants containing HSP70A-RBCS2-ble (AR-ble) constructs harboring deletions/mutations in the A promoter. We identified histone modifications at transgenic R promoters indicative for repressive chromatin, i.e. low levels of histone H3/4 acetylation and H3-lysine 4 trimethylation and high levels of H3-lysine 9 monomethylation. Transgenic A promoters also harbor lower levels of active chromatin marks than the native A promoter, but levels were higher than those at transgenic R promoters. Strikingly, in AR promoter fusions, the chromatin state at the A promoter was transferred to R. This effect required intact HSE4, HSE1/2 and TATA-box in the A promoter and was mediated by heat shock factor (HSF1). However, time-course analyses in strains inducibly depleted of HSF1 revealed that a transcriptionally competent chromatin state alone was not sufficient for activating the R promoter, but required constitutive HSF1 occupancy at transgenic A. We propose that HSF1 constitutively forms a scaffold at the transgenic A promoter, presumably containing mediator and TFIID, from which local chromatin remodeling and polymerase II recruitment to downstream promoters is realized.

INTRODUCTION

The capability of eukaryotic cells to dynamically change the level of chromatin condensation—from unpacking large chromosomal regions down to the repositioning of individual nucleosomes—has enabled them to regulate gene expression at a level unknown to prokaryotes (1). Such changes in chromatin structure are largely mediated by a plethora of post-translational modifications that occur mainly at the N-terminal tails of core histones H3 and H4 and at the N- and C-terminal tails of core histones H2A and H2B (2–4). Regulation of gene expression at the chromatin level often becomes evident and problematic when one attempts to express transgenes at ectopic sites within the genome. At such sites, transgenic promoters might not be accessible to transcription factors because of repressive chromatin structures at the integration site (5). This problem is particularly evident in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, where histone modifications characteristic for active chromatin are low (∼20% H3 acetylation), whereas those typical for inactive chromatin are high [∼80% monomethylation of lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4)] (6,7).

Transgenes may also become actively silenced by protein factors that place specific histone modifications onto nucleosomes at the transgene loci to trigger chromatin compaction—a mechanism that may have evolved to protect the genome from invading DNA (8). Several such factors have been identified in Chlamydomonas: one of them is MUT11, a homolog of human WDR5, which presents lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4) for methylation (9). In mut11 knock-out strains single-copy transgenes and dispersed transposons became activated (10). MUT11 was shown to interact with SET domain histone methyltransferases and RNAi-mediated suppression of SET1p, a trithorax-like H3K4 histone methyltransferase, resulted in a reduction of levels of H3K4 monomethylation, a histone mark associated with transcriptionally repressed loci (6). Another factor is the SU(VAR)3-9-related protein SET3p. Suppression of SET3p by RNAi released the transcriptional silencing of tandemly repeated transgenes and correlated with a partial loss of levels of monomethylated lysine 9 at histone H3 (H3K9), whereas repressed, single-copy euchromatic transgenes and dispersed transposons were not reactivated (11). Again another factor is the MUT9p kinase that phosphorylates threonine 3 at histone H3 and residues at histone H2A and is required for long-term, heritable gene silencing (8). Furthermore, the Chlamydomonas enhancer of zeste homolog (EZH) catalyzes methylation of lysine 27 at histone H3. RNAi-mediated suppression of EZH in Chlamydomonas resulted in a global increase in levels of histone H3K4 trimethylation and H4 acetylation, both characteristic for active chromatin, thus leading to the release of retrotransposons and of silenced, tandemly repeated transgenes (12). Finally, Yamasaki et al. (13) found that silencing of a transgenic Rubisco small subunit 2 (RBCS2) promoter, driving the expression of an inverted repeat construct, was associated with low levels of histone H3 acetylation and high levels of H3K9 monomethylation at the transgenic promoter. Deletion of the Elongin C gene, which is a component of some E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes, released silencing of the transgenic RBCS2 promoter. The activated promoter was characterized by high levels of H3 acetylation and low levels of H3K9 monomethylation (14).

In contrast to the many factors identified that mediate (trans)gene silencing, only little is known about factors counteracting transgene silencing. More by chance we have identified a system that seems to be capable of counteracting transgene silencing: the Chlamydomonas heat shock protein 70A (HSP70A) promoter. When transgene expression is driven directly by the HSP70A (A) promoter, or when the A promoter is fused upstream of other Chlamydomonas promoters, transgene expressing Chlamydomonas transformants are found at high frequency (15,16). In fact, the HSP70A–RBCS2 promoter fusion (AR) turned out to be the most efficient of several promoter fusions tested and today probably is the most frequently used promoter for transgene expression in Chlamydomonas (17–27). Moreover, the AR promoter seems to be functional also in other microalgae (28,29).

To understand the mechanism underlying the activating effect of the A promoter on other promoters, we used the bacterial resistance gene ble, conferring resistance to zeocin (30). When directly selecting for zeocin resistance, we observed that transformation rates were more than doubled if the ble gene was driven by an AR promoter fusion compared with the R promoter alone. Surprisingly, average ble transcript levels in transformants generated with either construct were the same. This apparent contradiction was resolved in experiments where (A)R-ble constructs were co-transformed with the ARG7 gene, and selection was on arginine prototrophy. Here, the fraction of co-transformants expressing the R-ble construct was only 20%, whereas that expressing the AR-ble construct was 64% (31). Hence, increased (co-)transformation rates resulted from the ability of the A promoter to counteract transcriptional gene silencing of the R-ble transgene.

Two regions within the A promoter were mapped that independently counteract R-ble transgene silencing: a proximal region confined to nucleotides −22 to −285 relative to the translational start codon and a distal region located upstream of position −285 (31) (Figure 1A). While the proximal region exhibits a strong spacing dependence toward the R promoter, the distal region seems to act spacing-independent. Using DNaseI hypersensitivity assays at the native HSP70A gene locus, two strong, constitutive DNaseI hypersensitive sites were mapped to heat shock element 1 (HSE1)/TATA-box and to HSE4 in the proximal and distal HSP70A promoter, respectively (33) (Figure 1A), suggesting that protein factors constitutively occupying these sequence motifs might be mediating the anti-silencing effect. Various A promoter deletion/mutation constructs revealed that the anti-silencing effect indeed largely depended on functional HSE4 in the distal and functional HSE1/2 and TATA-box in the proximal region. Moreover, the ability of the mutated/deleted HSP70A promoter to exert the anti-silencing effect correlated with its ability to confer heat shock inducibility to the ble reporter gene (34). Hence, it seemed likely that the anti-silencing effect of the A promoter was mediated by heat shock transcription factors (HSFs).

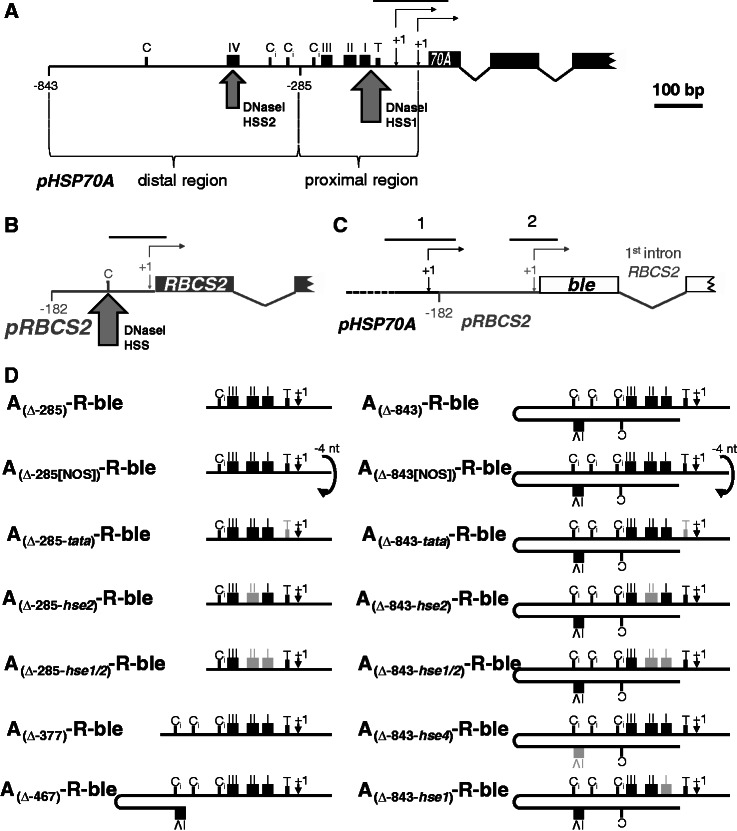

Figure 1.

Regions amplified from chromatin immunoprecipitates by qPCR and HSP70A promoter mutation/deletion constructs used in this study. Schematic drawings of the native HSP70A gene (black) (A), the native RBCS2 gene (grey) (B) and the ble transgene (white) driven by the HSP70A–RBCS2 tandem promoter (C). Non-coding regions are drawn as thin lines, coding regions as boxes. Thin-lined arrows indicate transcriptional start sites (+1), of which the HSP70A promoter has two (32). RBCS2 promoter deletion end points are given relative to the transcriptional start site. Large arrows mark the positions of DNaseI hypersensitive sites (HSS) as detected previously (33). Sequence motifs highlighted are CCAAT-boxes (C), inverted CCAAT-boxes (Ci), HSEs (black boxes with roman numbers) and a TATA-box (T, small black box). Black lines on top of the promoters designate the regions amplified by qPCR. (D) Overview of HSP70A promoter variants fused upstream of the RBSC2 promoter. HSP70A (A) promoter sequences are situated with optimal spacing upstream of the RBCS2 (R) promoter in all constructs except for those designated NOS (non-optimal spacing), which contain a 4-bp deletion (in lower case) in the GCTAGCttaaGAT NheI–AflII linker between both promoters (31). HSP70A promoter deletion end points are given relative to the translational start codon. The transcriptional start site indicated (+1) is that of promoter PA1 situated 89-bp upstream of the translational start codon (32). Light grey boxes designate mutated motifs with nucleotide substitutions as described earlier (34).

Two HSFs, termed HSF1 and HSF2, are encoded in the Chlamydomonas genome (35). In contrast to HSF2, HSF1 is a canonical HSF that combines properties typical for plant HSFs (heat shock inducibility, high sequence similarity to class A plant HSFs) with those typical for yeast HSF (constitutive trimerization, large size). HSF1-RNAi strains were unable to induce the expression of heat shock genes and proteins and were highly thermosensitive, thus indicating that HSF1 is a key regulator of the stress response in Chlamydomonas (36).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments revealed that (increased) binding of HSF1 to its target promoters after heat shock resulted in increased acetylation of histones H3 and H4, followed by nucleosome eviction and transcriptional activation (37). The A promoter also under non-stress conditions was found to be in a particularly open chromatin state, as judged by high levels of histone H3/4 acetylation and low nucleosome occupancy. This constitutively open chromatin state seems to be mediated by HSF1, as H3 acetylation levels at the A promoter were significantly reduced in HSF1-RNAi/amiRNA strains compared with wild-type strains (37). Hence, it seems possible that this open chromatin state spreads from the A promoter into its close vicinity and thereby counteracts the silencing of downstream promoters, as suggested previously (31).

In this work, we show that in a transgene setting the A promoter indeed realizes a transcriptionally more competent chromatin state at the downstream R promoter, as judged from elevated levels of H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3—both characteristic for active chromatin—and reduced levels of H3K9me1 indicative for repressive chromatin. Surprisingly, this is not sufficient for their activation by the transgenic A promoter. Rather, constitutive HSF1 occupancy at the A promoter is essential for R promoter activation, presumably mediated by the ability of HSF1 to organize a scaffold from which the R promoter is supplied with RNA polymerase II.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and cultivation conditions

C. reinhardtii strains cw15–302 (cwd, mt+, nit1−, arg7−) and cw15–325 (cwd, mt+, arg7−), both kindly provided by R. Matagne, University of Liège, Belgium, were used as recipient strains for co-transformation. Strain cw15–302 was used for the experiments presented in Figures 2–5, and strain cw15–325 for those presented in Figures 6 and 7. Cells, supplemented with 50 µg/ml of arginine if required, were grown photomixotrophically to a density of 4–7 × 106 cells/ml in Tris–acetate–phosphate (TAP) medium (38) on a rotary shaker at 24°C and ∼30 µE m−2 s−1. (Co-)transformations were done with 1 × 108 cells using the glass beads method (39) or electroporation (40). pCB412, containing the wild-type ARG7 gene, was linearized with EcoRI, pHyg3 (41) with HindIII and (A)R-ble constructs with NcoI. For co-transformation experiments, 200 ng of plasmid containing the selection marker (pCB412 or pHyg3) and 1 µg of the (A)R-ble constructs were used. Immediately after vortexing with glass beads or electroporation, cells were spread on TAP agar plates. Plates were supplemented with 10 µg/ml of hygromycin when cw15–325 strains, already containing the pNIT1–HSF1–amiRNA construct (42), were co-transformed. For direct transformation of the latter strains with (A)R-ble constructs, cells after electroporation were directly spread onto TAP agar plates supplemented with 5 µg/ml of zeocin.

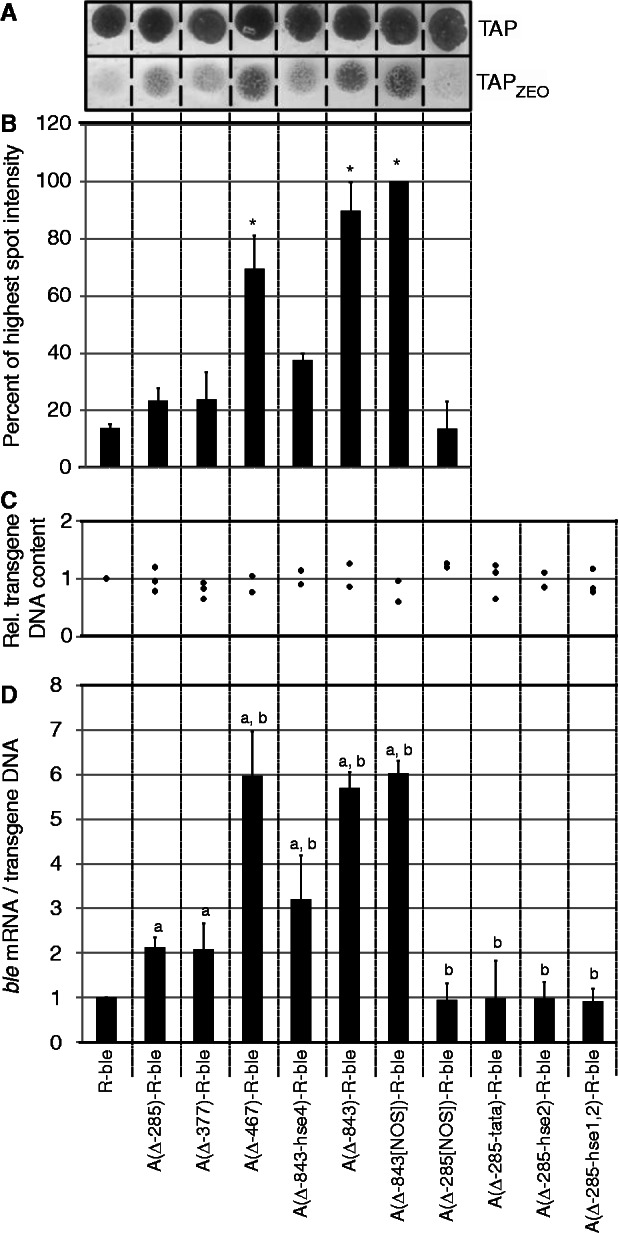

Figure 2.

Mutation/deletion of HSEs or TATA-box in the HSP70A promoter impairs its activating effect on R-ble transgene expression. (A) Spot test to determine the fraction of zeocin-resistant co-transformants. Pools of at least 200 co-transformants generated with the constructs indicated were grown in TAP medium and spotted on TAP–agar plates lacking zeocin (TAP) or supplemented with 1.5 µg/ml of the drug (TAPzeo). (B) Quantification of survival rates. Spots on zeocin-containing TAP agar plates were quantified by densitometry. Shown are averages and SEM (n = 2–3). Asterisks indicate the significance as determined by the All Pairwise Multiple Comparison Procedure (Fisher LSD Method) after successful ANOVA (P < 0.001). (C) Relative content of transgenic DNA in co-transformant pools. Relative copy numbers of transgenic constructs were determined by qPCR on extracted total DNA. Each diamond represents an independent experiment analyzed in triplicate. (D) Accumulation of ble mRNA relative to transgenic DNA in co-transformant pools. ble mRNA levels were quantified relative to those of CBLP2 by qRT–PCR, first normalized by the transgenic DNA content determined in (C), and subsequently to the normalized value determined for the co-transformant pool generated with R-ble. Error bars represent standard errors of two to three biological replicates, each analyzed in triplicate. Letters indicate the significance as determined by the Fisher LSD Method after successful ANOVA (P < 0.001). a, significant difference to R-ble; b, significant difference to A(Δ285)-R-ble.

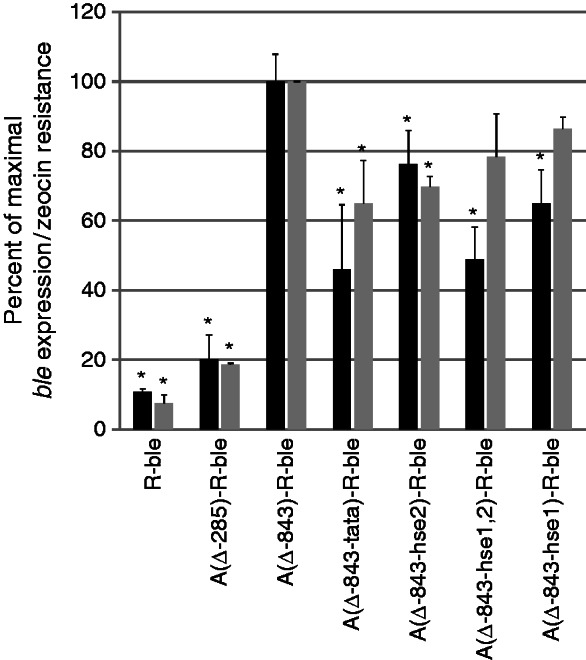

Figure 3.

Mutating HSE1/2 or the TATA-box in the full-length HSP70A promoter impairs its activating effect on R-ble transgene expression. Black bars indicate relative ble mRNA levels in co-transformant pools determined by qRT–PCR as described in Figure 2D. Error bars represent standard errors of two biological replicates, each analyzed in triplicate. Grey bars indicate survival rates of co-transformant pools determined as described in Figure 2A and B. Shown are averages and SEM (n = 2). Asterisks indicate the significance as determined by the Multiple Comparisons versus Control Group (Holm Sidak Method) after successful ANOVA (P < 0.001) compared with A(Δ843)-R-ble.

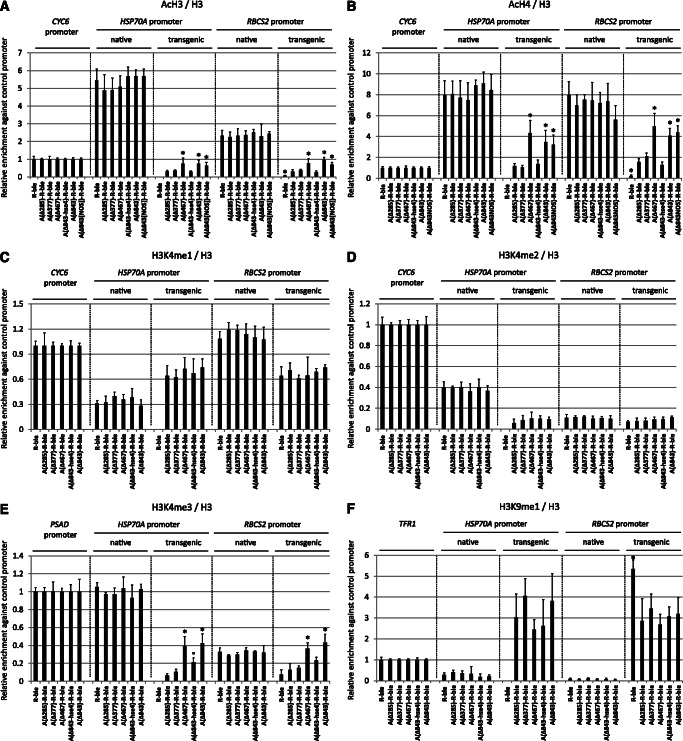

Figure 4.

Effects of variants of the distal HSP70A promoter on histone modifications at transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters. (A) Proximal and distal HSP70A promoter elements mediate increased levels of H3 acetylation at transgenic promoters. Chromatin fragments precipitated from co-transformant pools with antibodies against acetylated lysines 9 and 14 of histone H3 were quantified by qPCR. The enrichment relative to 10% input DNA was normalized with respect to histone H3 occupancy at the respective region (Supplementary Figures S3A–C). Values for each region investigated were normalized to that obtained for the native CYC6 promoter. Error bars indicate standard errors of two biological replicates, each analyzed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate the significance as determined by the Holm-Sidak method after successful ANOVA (P < 0.001). Circles indicate the significance of differences relative to co-transformant pools generated with the A(Δ-285)-R-ble construct (transgenic A promoters) or the R-ble construct (transgenic R promoters). The label ‘native’ refers to the native HSP70A or RBCS2 promoter in the strains bearing the indicated transgenes. (B) Proximal and distal HSP70A promoter elements mediate increased levels of H4 acetylation at transgenic promoters. ChIP was done using antibodies against acetylated lysines 5, 8, 12 and 16 of histone H4. Normalization was done as in (A). (C) Levels of H3K4 monomethylation at transgenic promoters are not affected by any motifs within the HSP70A promoter. ChIP was done using antibodies against monomethylated lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4me1). Normalization was done as in (A). (D) Levels of H3K4 dimethylation at transgenic promoters are not affected by any motifs within the HSP70A promoter. ChIP was done using antibodies against dimethylated lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4me2). Normalization was done as in (A). (E) The distal HSP70A promoter element mediates increased levels of H3K4 trimethylation at transgenic promoters. ChIP was done using antibodies against trimethylated lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4me3). Normalization was done as in (A), but using qPCR data from the native PSAD promoter. (F) Levels of H3K9 monomethylation at transgenic RBCS2 promoters are reduced by the proximal HSP70A promoter. ChIP was done using antibodies against monomethylated lysine 9 at histone H3 (H3K9me1). Normalization was done as in (A), but using qPCR data from telomere flanking region 1 (TFR1).

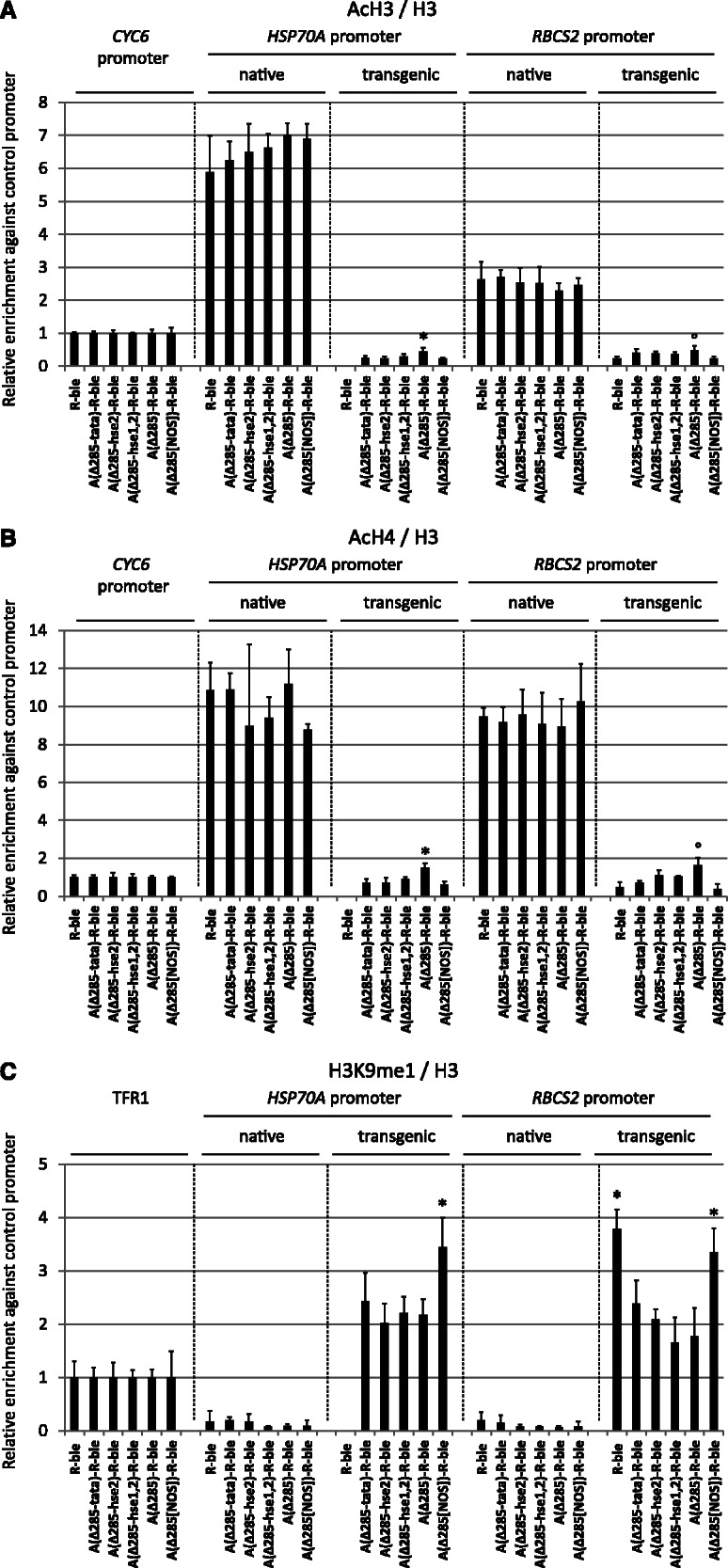

Figure 5.

Effects of variants of the proximal HSP70A promoter on histone modifications at transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters. (A) Optimal spacing and intact HSE2 and TATA-box in the proximal HSP70A promoter are essential for mediating increased H3 acetylation at transgenic promoters. Quantification of precipitated chromatin fragments and significance tests were done as described in Figure 4A using data on nucleosome occupancy shown in Supplementary Figures S3D and S3E. (B) Optimal spacing and intact HSE2 and TATA-box in the proximal HSP70A promoter are essential for mediating increased H4 acetylation at transgenic promoters. ChIP was done using antibodies against acetylated lysines 5, 8, 12 and 16 of histone H4. Normalization was done as described in Figure 4A. (C) Optimal spacing but not intact HSE2/TATA-box are required for reducing H3K9 monomethylation levels at transgenic promoters. ChIP was done using antibodies against monomethylated lysine 9 at histone H3 (H3K9me1). Normalization was done as described in Figure 4F.

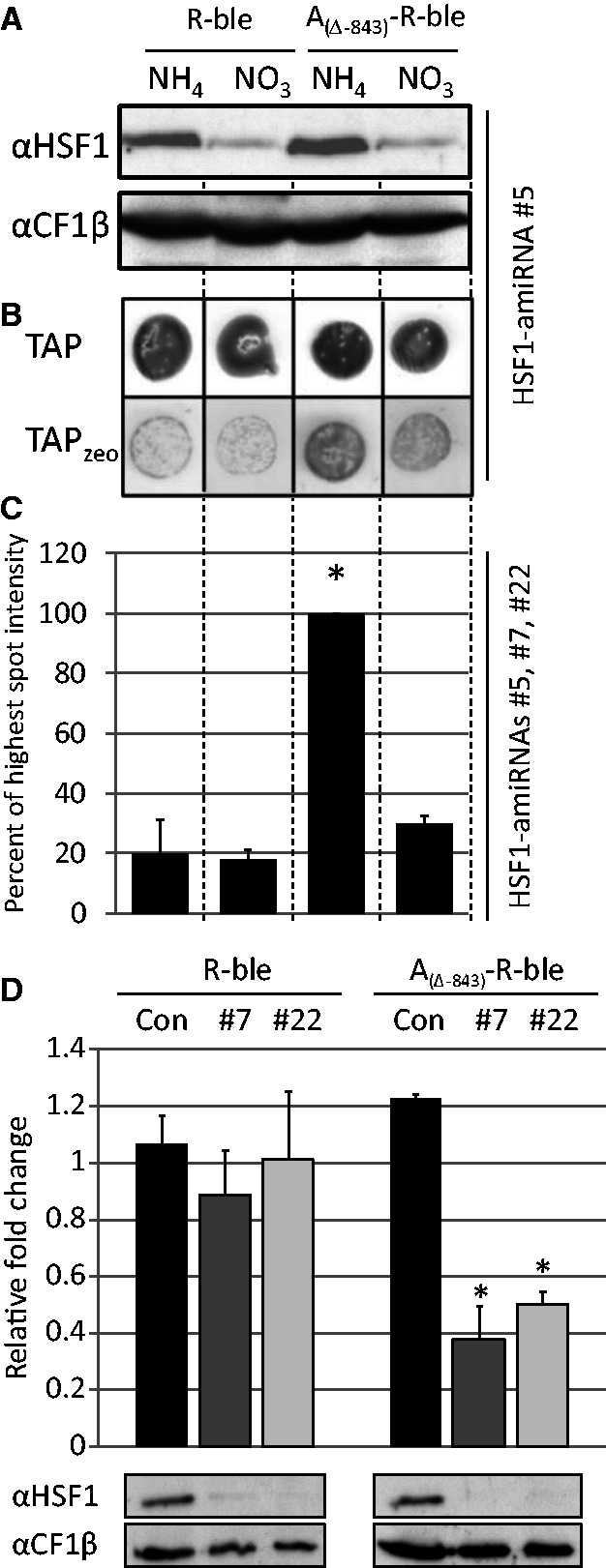

Figure 6.

HSF1 counteracts transcriptional transgene silencing. (A) Inducible downregulation of HSF1 in co-transformant pools generated with R-ble and AR-ble constructs. Constructs R-ble and A(Δ-843)-R-ble were co-transformed with the aph7’’ gene into strains already containing an HSF1-amiRNA construct under control of the NIT1 promoter. Co-transformant pools were grown for 48 h in medium containing NH4Cl or KNO3. Whole-cell proteins corresponding to 2 µg chlorophyll were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. Shown is a typical experiment with HSF1-amiRNA strain #5 as background. (B) Spot test to determine the fraction of zeocin resistant co-transformants. Co-transformant pools were grown in NH4- or NO3-containing medium and spotted on plates with the respective nitrogen source lacking (TAP) or containing (TAPzeo) 5 µg/ml zeocin. (C) Quantification of survival rates. Spots on zeocin-containing TAP agar plates were quantified by densitometry. Shown are averages and standard errors from three independent co-transformant pools generated with HSF1-amiRNA strains #5, #7 and #22 as recipients. Asterisks indicate the significance as determined by the Fisher LSD Method after successful ANOVA (P < 0.001). (D) Analysis of relative changes in ble mRNA levels upon depletion of HSF1 in single-clone transformants. R-ble and A(Δ-843)-R-ble constructs were transformed into a control strain (black) and into HSF1-amiRNA strains #7 (dark grey) and #22 (light grey) and directly selected for resistance to zeocin. Relative fold changes in ble mRNA levels in cells shifted from NH4- to NO3-containing medium for 48 h were quantified by qRT-PCR with CBLP2 as control. Error bars indicate standard errors from experiments done with two independent transformants in the two strain backgrounds, each analyzed in triplicate. Whole-cell proteins extracted in parallel were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in (A). Asterisks indicate the significance as determined by the Holm-Sidak method after successful ANOVA (P < 0.001).

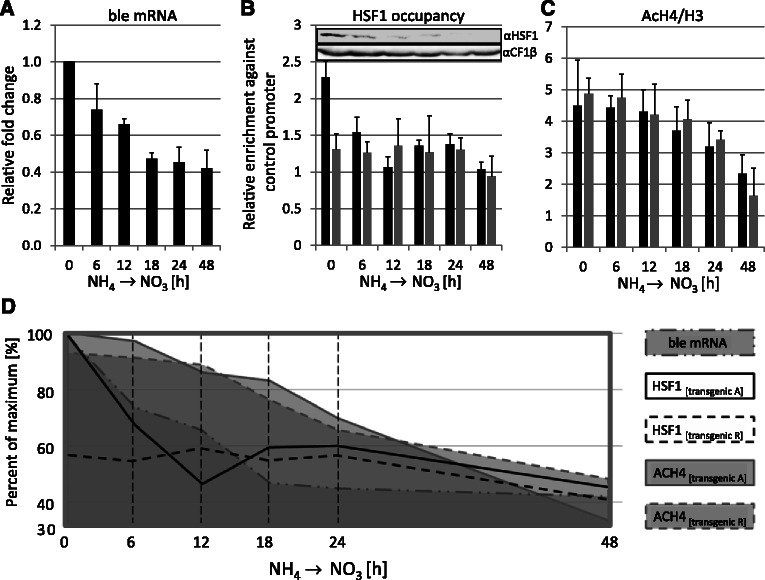

Figure 7.

Time course analysis of the sequence of events at transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters during HSF1 depletion. (A) Transgene expression is affected already 6 h after shifting to nitrate. Cells from two individual HSF1-underexpressing transformants (in HSF1-amiRNA strain #7) harboring the A(Δ-843)-R-ble construct were shifted from from NH4- to NO3-containing medium and ble mRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR as described in Figure 2D. Shown are fold changes in transcript accumulation relative to the non-shifted state. Values derive from two biological replicates, each analyzed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard errors. (B) HSF1 occupancy at transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters declines already 6 h after shifting to NO3. Transgenic promoters HSP70A (black bars) and RBCS2 (grey bars) were precipitated with affinity-purified antibodies against HSF1 and quantified by qPCR. The enrichment relative to 10% input DNA was normalized to the values obtained for the CYC6 promoter. Values derive from two biological replicates, each analyzed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard errors. The inset shows an immunoblot analysis of HSF1 levels in the time-course samples that was carried out as described in Figure 6A. (C) Levels of histone H4 acetylation at the transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters decline slowly. ChIP was done as described in (B) but using antibodies against acetylated lysines 5, 8, 12 and 16 of histone H4. Values were normalized to histone H3 occupancy data as shown in Supplementary Figure S3F. (D) Graphical overview of results. The data from (A–C) are given as percent of the respective maximal values.

Spotting test to compare relative resistances to zeocin

Cells were cultured in liquid TAP medium to a density of ∼5 × 106 cells/ml, and 105 cells were spotted on TAP agar plates supplemented with 1.5 µg/ml of zeocin (for cw15–302) or 5 µg/ml of zeocin (for cw15–325). Then the plates were incubated for 7–10 days under constant white fluorescent light at 24°C and ∼30 µE m−2 s−1. Cell growth on TAP–agar plates was quantified by densitometry using the Quantity One-4.5.1 program (Bio-Rad).

Plasmid constructions

The generation of constructs R-ble, A(Δ-285)-R-ble, A(Δ-285[NOS])-R-ble, A(Δ-843)-R-ble and A(Δ-843[NOS])-R-ble is described (31), and that of constructs A(Δ-843-hse4)-R-ble, A(Δ-285-tata)-R-ble, A(Δ-285-hse2)-R-ble and A(Δ-285-hse1/2)-R-ble as well (34). Construct A(Δ-467)-R-ble was made by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplification of a 689-bp fragment on pMS188 (A(Δ-843)-R-ble) using primers 5′-GGACTAGTCGAAGGGCCGCGACGGT-3′ and 5′-ATCCTGGCCATTTTAAGATGTTG-3′, and ligation of the SpeI–BstEII-digested PCR product into pMS171 (A(Δ-285)-R-ble) cleaved with the same enzymes. Construct A(Δ-377)-R-ble was made by ligating a 287-bp fragment released from XbaI–BstEII-digested PCB478 (43) into SpeI–BstEII-digested pMS171. Constructs A(Δ-843-tata)-R-ble, A(Δ-843-hse1)-R-ble, A(Δ-843hse1,2)-R-ble and A(Δ-843-hse2)-R-ble were made by PCR amplification of 507-bp fragments on constructs pMS428 (A(Δ-285-tata)-R-ble), pMS424 (A(Δ-285-hse1)-R-ble), pMS478 (A(Δ-285-hse1,2)-R-ble) and A(Δ-843-hse2)-R-ble, respectively, using primers 5′ AAATTACATATGTCTGCGTGACGGCGGGGAGCTCGCTGA-3′ and 5′-ATCCTGGCCATTTTAAGATGTTG-3′. PCR products were digested with NheI and NdeI and ligated into NheI–NdeI-digested pMS188 (A(Δ-843)-R-ble). Correct cloning of all constructs was verified by sequencing.

Protein extraction, immunodetection, RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR

Protein extraction, immunoblot analyses, RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase (qRT)–PCR were done as described previously (37). qRT–PCR was performed using the StepOnePlus RT–PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and the Maxima SYBR Green kit from Fermentas. Each reaction contained the vendor’s master mix, 100 nM of each primer and cDNA corresponding to 10 ng input RNA in the reverse transcriptase reaction. The reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, followed by cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 60 s, up to 40 cycles. Controls without template were always included. ΔCt values were determined by subtracting Ct values obtained for CBLP2 housekeeping gene transcripts from those obtained for ble transcripts.

Preparation of genomic DNA and qPCR

Total DNA was extracted from co-transformant pools as described previously (44). In all, ∼20 ng of extracted DNA was used for qPCR using the same settings as for qRT–PCR (see earlier in the text). Controls without template were always included. ΔCt values were determined by subtracting Ct values obtained for the endogenous CYC6 promoter [using primers reported earlier (37)] from those obtained for transgenic R promoters (using primers amplifying region 2 in Figure 1C; Supplementary Figure S2). ΔCt values were all normalized to those obtained for the co-transformant pool generated with the R-ble construct.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

ChIP assays and the analyses of immunoprecipitated DNA by real-time PCR were performed as described previously (37,45). Antibodies used for ChIP were as follows: histone H3 (ab1791; Abcam), histone H3K9me1 (ab9045; Abcam), histone H3Ac (06–599; Millipore), histone H4Ac (06–866), histone H3K4me3 (07–473; Millipore), histone H3K4me2 (07–030; Millipore) and histone H3K4me1 (ab8895; Abcam). Affinity-purified antibodies against VIPP2 (46) were used as negative control. Normalization of ChIP data was performed depending on the analyzed chromatin mark. ChIP data obtained with antibodies against AcH3, AcH4, H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 were normalized relative to the CYC6 promoter. In case of H3K9me1, a region downstream of the repetitive telomere region at chromosome 2 (telomere flanking region, TFR) was used for normalization (47). The ChIP data gained with an antibody against H3K4 trimethylation was normalized against the PSAD promoter, at which we found the H3K4 trimethylation mark to be strongly enriched.

RESULTS

HSE4 in the distal, and HSE1/2, TATA-box and spatial setting in the proximal HSP70A promoter are crucial for its anti-transgene silencing activity

Our first goal was to investigate which cis-regulatory elements within the HSP70A (A) promoter are required for counteracting silencing of the transgenic RBCS2 (R) promoter. For this, we co-transformed an arginine auxotrophic C. reinhardtii strain with the ARG7 wild-type gene and constructs where the ble gene is driven by the R promoter alone (R-ble) or by the AR fusion promoter (AR-ble) (Figure 1C). We used 14 different variations of AR promoter fusions, in which sequence elements of the A promoter were deleted/mutated, or where the A promoter was fused to the R promoter with a non-optimal spacing (Figure 1D) (31). On the one hand, the constructs were designed to address the role of heat shock element (HSE) 4, two inverted and a regular CCAAT-box in the distal A promoter, and the relevance of their spatial setting toward the R promoter. On the other hand, they were intended to address the roles of HSEs 1 and 2 and the TATA-box in the proximal A promoter and of their spacing toward the R promoter. To average out position effects, we pooled at least 200 arginine prototrophic co-transformants generated with each construct—this pool size was determined previously to be at least required for this purpose (34).

As a simple method to determine the fraction of co-transformants expressing the ble transgene, we spotted cells from cultured co-transformant pools onto zeocin-containing agar plates and quantified the density of cells growing on the drug (Figures 2A and B). Moreover, to also use a more accurate method, we used qPCR to determine how much ble transcript accumulated per transgene copy in the respective co-transformant pool. Co-transformation rates, as determined from the ratio of transgenic R promoters to native CYC6 promoters, were similar for each construct type (Figure 2C), thus ruling out an effect of the A promoter on the efficiency of transgene insertion. Although the results from the simple spot assay and the labor-intensive qPCR analysis correlate well (compare Figures 2B and D), we will only refer to the more accurate qPCR data.

We found that twice as many co-transformants express the ble transgene when they contain an AR-ble construct where the Δ-285 A promoter is preceding the R promoter compared with the R-ble construct. This stimulatory effect of the proximal A promoter is entirely abolished when HSE2, HSEs 1 and 2 or the TATA-box is mutated, or when the spatial setting between A and R promoters is non-optimal. These data indicate that HSE2, TATA-box and spacing play crucial roles for the anti-silencing activity of the proximal A promoter. The stimulatory effect of the proximal A promoter was not increased when it was extended by two inverted CCAAT-boxes (Δ-377 deletion), therefore, ruling out a contribution of these sequence motifs.

We observed that the fraction of expressing ble transgenes in co-transformant pools was increased ∼6-fold when co-transformants contained an AR-ble construct where the Δ-843 A promoter is fused upstream of the R promoter compared with an R-ble construct (Figure 2D). The stimulatory effect was the same when the Δ-467 A promoter was used, hence, ruling out a contribution of the regular CCAAT-box. The stimulatory effect was also fully observed when the Δ-843 A promoter was fused to the R promoter with non-optimal spacing, thus suggesting that the distal A promoter exerts its anti-silencing activity spacing-independently. Mutation of HSE4 reduced the stimulatory effect of the A promoter by half, which indicates a crucial role for HSE4, but it also points to a minor role of yet unknown sequences in the distal A promoter.

We wondered whether the anti-silencing effect mediated by the distal A promoter is independent of the HSE1/2 and TATA motifs found in the proximal promoter to be important for counteracting transgene silencing. To test this, we mutated HSE1/2 and the TATA-box in the Δ-843 AR-ble construct and analyzed zeocin resistance and ble transgene expression levels in co-transformant pools containing the respective constructs. As shown in Figure 3, mutation of HSE1 or HSE2 reduced the fraction of expressing ble transgenes in co-transformant pools by 25–35% and mutation of HSE1/2 and TATA-box even by ∼50% when compared with co-transformants containing the intact Δ-843 AR-ble construct. However, the fraction of expressing ble transgenes was still ∼2.5-fold higher in co-transformant pools generated with Δ-843 AR-ble constructs containing mutated HSE1/2 or TATA-box when compared with those generated with the Δ-285 AR-ble construct. These data indicate that motifs in the distal A promoter cooperate with HSE1/2 and TATA-box in the proximal A promoter to exert the anti-silencing effect.

The observations made here are in full agreement with those made in our previous study where the fraction of expressed ble transgenes in co-transformant pools was determined by RNA and DNA gel blot analyses (34). However, although in our earlier study we observed that the Δ-843 and the Δ-285 A promoters increased the fraction of expressing ble transgenes by 26.7- and 5.6-fold, respectively, we find increases in this study by only 6- to 10- and ∼2-fold, respectively (Figures 2D and 3; see Supplementary Figure S1 for a comparison of earlier and current data). As the values determined by qPCR correlate well with the resistance levels (Figures 2B, D and 3) and with values obtained from direct transformation rates (31), we consider them as quantitatively more reliable. We explain the discrepancy by a less efficient transfer of larger DNA fragments in DNA gel blots. This would result in an underestimation of copy numbers of larger transgenes in our earlier study and thus to an overestimation of ble transcripts per transgene for larger transgenes.

HSE4 in the distal HSP70A promoter mediates increased levels of histone H3 and H4 acetylation at transgenic promoters

To investigate whether the anti-silencing effect of the A promoter was realized by its ability to remodel close-by chromatin via histone modifications, as suggested previously (31), we applied the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) technique to the co-transformant pools described earlier in the text. We designed specific amplicons to compare the chromatin states of native and transgenic promoters (Figure 1A–C and Supplementary Figure S2). Moreover, to allow for an analysis of the individual chromatin states of transgenic A and R promoters in the AR promoter fusion, we chose harsh sonication conditions to generate chromatin fragments of ∼200 bp, essentially corresponding to mononucleosomes (45).

In the first set of experiments, we focused on potential effects on histone modifications mediated by factors binding to HSE4, regular and inverted CCAAT-boxes in the distal A promoter and their spatial setting toward the R promoter. Using antibodies against the unmodified C-terminus of histone H3, we first investigated nucleosome occupancy. Although nucleosome occupancy was up to 2-fold lower at the native A promoter compared with transgenic A promoters, occupancy was about equally high at transgenic and native R promoters (Supplementary Figure S3; see Figure 8 for a compilation of all results). No significant differences in nucleosome occupancy between co-transformant pools generated with R-ble or any AR-ble construct were observed.

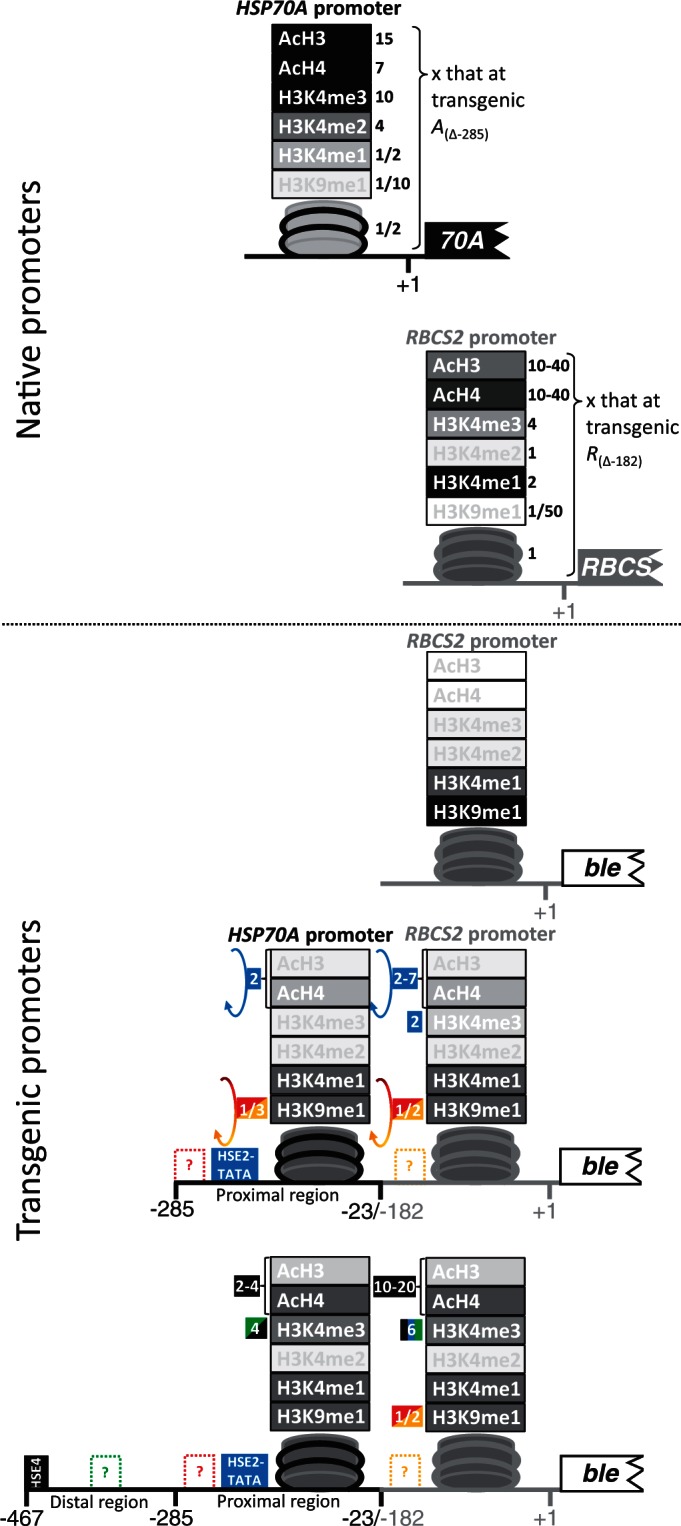

Figure 8.

Schematic presentation of nucleosome occupancy and modifications at the native and transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters as elucidated in this study. HSP70A promoter sequences are drawn as black, RBCS2 promoter sequences as grey lines. Promoter deletion end points are given as described in Figure 1. The nucleosome in the promoter regions studied by ChIP is schematically shown. Histone modifications are given on top of the nucleosome, where ‘acH3’ stands for acetylation at H3K9 and H3K14, ‘acH4’ for acetylation at H4K5, H4K8, H4K12 and H4K16, ‘H3K4me1-3’ for mono-, di- and trimethylation of H3K4 and ‘H3K9me1’ for H3K9 monomethylation. The darker the symbols for nucleosomes and histone modifications are drawn, the higher are their levels in the respective setting. Numbers in blue and black boxes give fold changes mediated by HSE2/TATA-box in the proximal, and by HSE4 in the distal region of the transgenic HSP70A promoter, respectively. Numbers in red, orange and green boxes give fold changes mediated by yet unknown sequence motifs within the promoters. Arrows indicate that fold changes depend on a proper spatial setting of HSP70A to RBCS2 promoter.

To analyze whether histone modification levels differ between native and transgenic A and R promoters, and whether the modification state at the transgenic R promoter is altered in AR promoter fusions, we performed ChIP with antibodies against acetylated histones H3 and H4. We first looked for histone acetylation because it is known to correlate with active transcription (2,4,37). As shown in Figure 4A and B, histone H3 and H4 acetylation levels were ∼15- and ∼7-fold higher at native compared with transgenic A promoters comprising the proximal promoter. H3 and H4 acetylation levels increased 2- to 4-fold at transgenic A promoters if they contained HSE4 in the distal region, an effect that occurred independent of the spatial setting of A to R promoter.

Strikingly, H3 and H4 acetylation levels at the native R promoter were 30–40 times higher than at the transgenic R promoter in the R-ble construct. Also here, H3 and H4 acetylation levels increased 5- to 7-fold if the transgenic R promoter was preceded by the proximal A promoter, and 10- to 20-fold if it was preceded by a complete A promoter. Again, this effect was spacing-independent, but fully depended on the presence of an intact HSE4, thus ruling out any contributions to H3/4 acetylation by the CCAAT-box or other sequences in the distal A promoter. As an extension of the proximal A promoter by sequences containing two inverted CCAAT-boxes (Δ-377 compared with Δ-285) had no effect on H3/4 acetylation levels at transgenic A or R promoters, these motifs apparently do not play any roles in A promoter-conferred histone acetylation.

The HSP70A promoter increases levels of H3K4 trimethylation and reduces levels of H3K9 monomethylation at transgenic promoters

Next, we used antibodies against mono-, di- and trimethylated lysine 4 at histone H3 (H3K4) for ChIP on this first set of co-transformant pools. Methylation levels at H3K4 are of particular importance, as H3K4 monomethylation (me1) was shown to be associated with silenced euchromatin in Chlamydomonas (6), whereas H3K4 trimethylation (me3) is generally observed at promoters of actively transcribed genes (2,4). As shown in Figure 4C, levels of H3K4me1 at the transgenic A promoter are about twice as high as those at the native A promoter, whereas the opposite was observed at the R promoters. Levels of H3K4me1 were about the same at the transgenic A and R promoters. None of the different A promoter variants in AR-ble constructs led to significant changes in levels of H3K4me1 at the transgenic promoters.

Figure 4D reveals that levels of H3K4 dimethylation (me2) were about four times higher at native A compared with transgenic A promoters, whereas they were the same at native and transgenic R promoters. As was observed for H3K4me1, levels of H3K4me2 were the same at both transgenic promoters and were not significantly altered by any A promoter variant in AR-ble constructs.

Interestingly, levels of H3K4me3 at the native R promoter were only about one-third of those detected at the native PSAD and HSP70A promoters (Figure 4E). Similar to H3/4 acetylation, levels of H3K4me3 were ∼10 times lower at transgenic A promoters (comprising only the proximal promoter) compared with the native A promoter and ∼4 times lower at transgenic compared with native R promoters. H3K4me3 levels increased >4-fold at transgenic A promoters containing the distal as compared with the A promoter containing only the proximal region. This effect was reduced 2-fold by mutation of HSE4, but as it was not entirely abolished, there seem to be sequences in the distal promoter region apart from HSE4 that contribute to H3K4me3 at the transgenic A promoter. Similarly, levels of H3K4me3 at the transgenic R promoter increased ∼2-fold if it was preceded by the proximal A promoter and ∼6-fold to levels similar to those detected at the native R promoter if the entire A promoter was upstream of the R promoter. Again, this effect was reduced by about half, but it was not completely abolished when HSE4 was mutated, thus supporting the notion that sequences apart from HSE4 in the distal A promoter contribute to H3K4me3 at the transgenic promoters. As H3K4me3 levels at the transgenic promoters were not increased in co-transformant pools generated with constructs A(Δ-843)-R-ble versus A(Δ-467)-R-ble and A(Δ-377)-R-ble versus A(Δ-285)-R-ble, we can rule out contributions to H3K4me3 by regular and inverted CCAAT-boxes, respectively (Figure 4E).

Another important methylation mark is that on lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9), as levels of H3K9me1 were shown previously to be enriched at silenced transgene promoters in Chlamydomonas (11,13,14). ChIP using antibodies against H3K9me1 on the first set of co-transformant pools revealed that H3K9me1 levels are very low at the native A and R promoters (Figure 4F). In contrast, H3K9me1 was ∼10 times higher at transgenic A promoters and ∼50 times higher at transgenic R promoters. Strikingly, if R promoters were preceded by A promoters, their average H3K9me1 levels were reduced almost by half to about the same levels observed at transgenic A promoters. This effect appears to be mediated by sequences within the proximal A promoter, as it was not enhanced by longer A promoter variants.

An optimal spacing between the proximal HSP70A promoter and the RBCS2 promoter is crucial for increasing levels of H3/4 acetylation and reducing levels of H3K9me1 at transgenic promoters

We next used a second set of co-transformant pools generated with constructs that allow investigating the roles of HSE1/2, TATA-box and their spatial setting toward the R promoter on histone modifications at transgenic promoters. Here, we only analyzed H3/4 acetylation and H3K9me1 levels. As shown in Figure 5A and B, we could reproduce that in co-transformant pools generated with the A(Δ-285)R-ble construct, acetylation levels at histones H3 and H4 are ∼15- and ∼7-fold higher at the native compared with the transgenic A promoter, and that both acetylation marks are 10- to 20-fold higher at the native compared with the transgenic R promoter. These already low levels of H3/4 acetylation at the transgenic A and R promoters decreased further when HSE2, HSE1/2 or the TATA-box were mutated or when the spacing between A and R promoters was non-optimal.

Regarding H3K9me1, we could also reproduce that levels are very low at the native and high at the transgenic promoters (Figure 5C). Again, if the proximal A promoter was fused upstream of the R promoter, H3K9me1 levels at the R promoter were reduced by about half. Surprisingly, this effect persisted when HSE1/2 or the TATA-box was mutated, but was abolished when A and R promoters were not optimally spaced. In the latter case, H3K9me1 levels were also ∼35% higher at the transgenic A promoter. The observations that non-optimal spacing between A and R promoters reduces H3 and H4 acetylation levels and increases levels of H3K9me1 at the transgenic A promoter are remarkable, as they suggest cooperation between yet unknown elements located in the A and R promoters.

HSF1 is the trans-acting factor through which transgene silencing is counteracted by the HSP70A promoter

The finding that HSE1/2 and HSE4 are the dominant sequence motifs mediating the anti-silencing effect of the A promoter suggested that HSF1 as the canonical heat shock factor in Chlamydomonas (36) might be the trans-acting factor mediating this effect. To test this, we co-transformed the aph7′′ gene, conferring resistance to hygromycin (41), with the R-ble and A(Δ-843)-R-ble constructs into Chlamydomonas strains harboring an HSF1–amiRNA construct driven by the NIT1 promoter. By switching the nitrogen source from ammonium to nitrate, expression of the HSF1–amiRNA is induced, and HSF1 is diluted out by growth [Figure 6A; (42)]. Hence, if HSF1 was mediating the activation of the R-ble transgene, we expected a larger fraction of zeocin-resistant clones in AR-ble co-transformant pools only in the presence of ammonium. As shown in Figure 6B and C, this expectation was indeed met: when grown on ammonium, the fraction of zeocin-resistant clones was ∼5 times larger in AR-ble compared with R-ble co-transformant pools. However, when grown on nitrate, the fraction of drug-resistant clones in AR-ble co-transformant pools declined ∼3-fold. The nitrogen source had no influence on the fraction of zeocin-resistant clones in R-ble co-transformant pools.

To substantiate these findings, we also determined the accumulation of ble transcripts in AR-ble and R-ble single-clone transformants grown on ammonium and nitrate. As shown in Figure 6D, ble transcript levels declined ∼3-fold when AR-ble transformants generated in PNIT1–HSF1–amiRNA strain backgrounds were grown on nitrate compared with ammonium. The reduction in ble transcript levels correlated with a strong reduction in HSF1 protein levels. In contrast, ble transcript levels in AR-ble transformants generated in the wild-type background were unaffected by the nitrogen source. A change of the nitrogen source had no effect on ble transcript levels in R-ble transformants, no matter whether they were generated in the wild-type or PNIT1–HSF1–amiRNA strain background. Accordingly, the reduction in HSF1 protein levels in the latter did not affect ble mRNA accumulation. Over all, these data strongly suggest that HSF1 is the major trans-acting factor by which the A promoter counteracts transcriptional silencing of the AR-ble transgene.

Not a transcriptionally competent chromatin structure, but HSF1 occupancy is crucial for R-ble transgene expression

With the inducible HSF1–amiRNA lines, we had a tool at hand that allowed us to investigate how fast histone modifications at the transgenic promoters are altered on depletion of HSF1, and how this correlates with transgene expression. For this, we grew single-clone transformants containing the A(Δ-843)-R-ble construct in the PNIT1–HSF1–amiRNA background on ammonium, shifted cells to medium containing nitrate to induce HSF1 depletion, and took six samples during a 48-h time-course. In these samples, we detected HSF1 occupancy and H4 acetylation at the transgenic A and R promoters by ChIP and ble transcript levels by qRT–PCR. We restricted our analysis to H4 acetylation because this mark was most dramatically affected by the A promoter and because the decline of H3K9me1 levels was independent of HSEs and thus unlikely to be mediated by HSF1. As shown in Figure 7B, HSF1 constitutively occupies the transgenic A promoter also under non-stress conditions, thus corroborating earlier results with the native A promoter (37). Binding of HSF1 to the transgenic R promoter was not detected, thus confirming that our sonication conditions indeed allow a separation of the A and R promoters in chromatin-embedded AR-ble transgenes. Concomitantly with HSF1 depletion, HSF1 occupancy at the transgenic A promoter declined and reached background levels already 12 h after shifting the nitrogen source. ble mRNA levels declined by about half within 18 h after shifting the nitrogen source with slightly delayed kinetics when compared with those of HSF1 occupancy (Figure 7A). Surprisingly, levels of H4 acetylation declined at both, transgenic A and R promoters with much slower kinetics than HSF1 occupancy and ble transcripts (Figure 7C and D). These data indicate that the activity of the transgenic R promoter requires the constitutive presence of HSF1 at the A promoter, and that a more transcriptionally competent chromatin structure alone is not sufficient. In that case, we would have expected similar kinetics for HSF1 occupancy, ble mRNA accumulation and H4 acetylation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we dissect the mechanisms underlying the activation effect of the HSP70A (A) promoter on downstream promoters in a transgene setting in the unicellular green alga C. reinhardtii. Our approach allows for obtaining an average picture of the chromatin state of transgenic A and RBCS2 (R) promoters by investigating pools of hundreds of individual transformants, thus averaging out variation by position effects. As the spot assays shown in Figure 2A demonstrate a homogenous distribution of drug-resistant cells, transgene copies are activated by the A promoter in a large fraction of co-transformants.

Features of the chromatin state at native versus transgenic HSP70A and RBCS2 promoters

We found that the native A promoter exhibits a chromatin state that is characteristic for active promoters (2,4,6,11,13,14,37), i.e. relatively low nucleosome occupancy, high levels of H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3, and low levels of H3K4me1 and H3K9me1 (Figures 4, 5 and 8, and Supplementary Figure S3). In contrast, the native R promoter, although considered a highly active promoter (48,49), exhibits a chromatin state that combines characteristics of active and inactive promoters (active: high levels of H4 acetylation, intermediate levels of H3 acetylation and H3K4me3, low levels of H3K9me1; inactive: relatively high nucleosome occupancy, very high levels of H3K4me1). These data corroborate and extend our previous observations (37,45) and suggest that in Chlamydomonas, histone acetylation might dominate over the H3K4 methylation state. However, the chromatin state of more Chlamydomonas promoters needs to be determined to elucidate whether this is the rule or whether the R promoter is exceptional.

Histone modifications at transgenic R promoters on average are enriched by marks typical for repressive chromatin, i.e. low levels of H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3 and high levels of H3K4me1 and H3K9me1 (Figure 8). However, average levels of H3K4me1 at transgenic R promoters are only half of those detected at the native R promoter, therefore, questioning whether high levels of H3K4me1 are generally associated with silent chromatin in Chlamydomonas, as suggested previously (6). Again, more promoters need to be studied to draw general conclusions.

Compared with the native A promoter, the average chromatin state at transgenic A promoters also is dominated by features characteristic for repressive chromatin, i.e. relatively high nucleosome occupancy, low levels of H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3 and high levels of H3K4me1 and H3K9me1. The average levels of H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3 are significantly higher at transgenic full-length A promoters containing intact HSE4, but still do not reach the levels detected at the native A promoter (Figure 8). However, average levels of H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3 are higher at short and long transgenic A promoters than at transgenic R promoters that are not preceded by an A promoter. Most strikingly, the transgenic A promoters appear to imprint their chromatin state to the transgenic R promoter fused downstream. In case of the full-length A promoter, this generates a chromatin state at transgenic R promoters that is equivalent to that detected at the native R promoter with respect to H3K4me3 and is about half of that at native R regarding H3/4 acetylation (Figure 8). The A promoter also reduces levels of the repressive chromatin mark H3K9me1 by about half if spaced properly toward the R promoter.

These data suggest that in Chlamydomonas transgenic R promoters [and probably also other promoters like HSP70B and β2TUB (15)] on average are silenced by the setting of repressive chromatin marks, and that the A promoter reduces the extent of repressive marks set at close by downstream promoters. An exception to this, however, seems to be the H3K4me2 mark. Although H3K4me3 is present only at promoters of active genes, H3K4me2 is present at both active and inactive euchromatic promoters (50). The role of H3K4me2 may be to determine a transcriptionally ‘permissive’ chromatin environment, whereas the trimethylated state may allow for an ‘active’ chromatin conformation (37,50). H3K4me3 and H3K4me2 localize near transcriptional start sites, but H3K4me2 peaks slightly downstream of H3K4me3 (51). Although H3K4me3 recruits histone acetyltransferases to acetylate nucleosomes, H3K4me2 recruits histone deacetylases to remove acetylation marks, presumably to demarcate promoter from downstream regions and to prevent spreading of histone acetylation into transcribed regions (52). Like H3K4me3, H3K4me2 is absent in heterochromatin and can thus be considered as a euchromatin mark (53). Accordingly, in Chlamydomonas, H3K4me2 levels are low at transgenic promoters, but in contrast to H3K4me3, H3K9me1 and H3/4 acetylation are not changed by any A promoter variant (Figure 4D).

The setting of repressive chromatin marks is not triggered by modifications on the transforming DNA

How can we explain the phenomenon that transgenic promoters in Chlamydomonas as a rule are embedded in repressive chromatin? A possible explanation is that the transgenic promoter attains the chromatin structure at its ectopic integration site and, as bulk chromatin in Chlamydomonas is repressive, the general outcome is a repressive chromatin state at the transgene locus. This idea seems to be supported by the finding that only 20% of bulk nucleosomes in Chlamydomonas carry the active mark of H3 acetylation (54), whereas 81.2% contain the repressive mark of monomethylated H3K4 (6,7). However, it seems to be not supported by the observation that only 15.6% of bulk nucleosomes are monomethylated at H3K9 (7). Thus, dictation of the transgene’s chromatin state by that prevailing at the random integration site might explain the low H3 acetylation and the high H3K4me1 levels, but not the strong enrichment of the repressive H3K9me1 mark.

Hence, it seems more likely that the H3K9me1 mark is set at nucleosomes that assemble on the foreign DNA right after its integration into the genome. But how is the foreign DNA recognized by the cell? DNA methylation triggered by the transcription of an inverted repeat construct was recently shown to correlate with high levels of H3K9me1, particularly at the promoter-driving expression of the inverted repeat (13). As we used plasmids purified from Escherichia coli for transforming Chlamydomonas, we reasoned that methyl marks on the plasmid DNA might trigger the setting of the H3K9me1 mark on nucleosomes formed at transgene loci. To test this idea, we compared the zeocin resistance levels of Chlamydomonas cells co-transformed with plasmid- or PCR-derived R-ble constructs. As we could not detect significant differences in resistance or transgene expression levels (Supplementary Figure S4), DNA modifications on the transforming DNA seem to not represent the trigger for the setting of the H3K9me1 mark. Using plasmid DNA extracted from dcm−/dam− bacteria also did not negatively affect transgene expression efficiency in mammalian cells (55).

An attractive hypothesis is that the setting of the H3K9me1 mark on nucleosomes formed on foreign DNA is mediated by Chlamydomonas SET3p (8,11) as part of the integration machinery. Such a mechanism would represent an efficient way for controlling invading DNA and might be worth of experimental testing.

Cis-regulatory elements within the HSP70A promoter mediating a modified chromatin state

As expected, the accumulation of ble transcripts and the levels of zeocin resistance strongly correlated with histone modifications characteristic for active chromatin at transgenic R promoters (Figures 2–5). Our deletion/mutation analysis of prominent cis-regulatory elements within the A promoter (i.e. HSEs, TATA-box and regular/inverted CCAAT-boxes) revealed that HSE4 in the distal and HSE1/2 and TATA-box in the proximal region of the A promoter are the dominant sequence elements required for mediating H3/4 acetylation and H3K4me3 at the transgenic promoters (Figure 8). Curiously, regarding the activation effect on transgene expression and the setting of active chromatin marks, HSE4 is more potent than HSE1/2 (Figure 8). In contrast, with respect to mediating heat shock inducibility, HSE1 and 2 are essential, whereas HSE4 is entirely dispensable (33). These data might indicate that the composition and/or the position of the HSEs within the promoter influence whether they act preferably in establishing transcriptionally competent chromatin or heat shock inducibility (56).

Interestingly, yet unknown sequences in the distal A promoter are responsible for setting part of the H3K4me3 marks at the transgenic promoters (Figure 8). And most strikingly, the reduction in levels of H3K9me1 by about half at the transgenic tandem promoters did not depend on CCAAT-boxes, HSEs or TATA-box, but apparently on yet unknown sequences within both promoters that need to be in a proper spatial setting toward another. As the H3K9me1 mark is likely to be a major determinant for promoter silencing in Chlamydomonas (11,13,14), the identification of these sequence elements and binding trans-acting factors would be of greatest interest for the construction of efficient expression vectors for this biotechnologically important organism.

HSF1 is a key trans-acting factor for counteracting transgene promoter silencing in Chlamydomonas

The identification of HSEs as prominent sequence elements for the activation of silenced promoters suggested a major role for HSFs in this process [(34); Figure 8]. By using strains that allow the inducible downregulation of HSF1 by amiRNA (42) we could in this study indeed verify HSF1 as the trans-acting factor mediating the effect: both ble transcript levels and resistance to zeocin declined in cells that contain AR-ble constructs and are depleted of HSF1, whereas HSF1 depletion had no effect on the already low transcript and resistance levels in cells containing R-ble (Figure 6).

In time-course analyses, we observed that, on depletion of cellular HSF1 levels, HSF1 binding to the A promoter declined rapidly, which, with a slight delay, was true also for ble transcript levels. Surprisingly, however, ∼18 h after inducing the HSF1–amiRNA construct, ble transcript levels were already down by half, whereas levels of H4 acetylation had hardly declined (Figure 7). In previous work, we found that the order of events on activation of the Chlamydomonas HSP22F gene by heat stress was binding of HSF1 to the promoter, histone acetylation, nucleosome remodeling and transcript accumulation (37). Hence, HSF1 obviously recruits histone acetyltransferase and other histone-modifying enzyme activities to target promoters. However, the presence of a nucleosome enriched with active chromatin marks at a transgenic R promoter apparently is not sufficient for its transcriptional activation. Rather, this seems to require the recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) by HSF1 either directly or via mediator/TFIID. In this regard, it is important to note that, under non-stress conditions, less Pol II accumulated at the yeast HSP82 promoter containing a mutated high-affinity HSE1 as compared with the wild-type promoter (57).

Mediator is a large complex that is highly conserved among all eukaryotes and forms the bridge between transcription factors bound at upstream regulatory elements and the general transcription machinery at the core promoter (58,59). Yeast mediator consists of 25 subunits and was shown to be important for genome-wide Pol II recruitment in vivo (60). In yeast, loss-of-function mutants of some mediator subunits enhanced the expression of heat shock genes under non-stress conditions while simultaneously limiting the extent of stress-induced expression, thus confirming a role of mediator in controlling HSP gene transcription in yeast (61). Yeast mediator remains at the promoter following the escape of Pol II and together with the transcriptional activator, TFIID, A, H and E may serve as a scaffold to facilitate transcriptional re-initiation (62,63). The constitutive presence of such a scaffold at the yeast HSP82 promoter is supported by the observation that mutation of its TATA-box or high-affinity HSE1, respectively, led to ∼3- and ∼15-fold reductions of HSP82 transcript accumulation under non-stress conditions (57,64).

The idea of a scaffold formed by HSF1, mediator and TFIID, A, H and E for Pol II recruitment under non-stress conditions also at the Chlamydomonas A promoter is supported by the following observations: first, Chlamydomonas and yeast HSF1 exist as constitutive trimers that also under non-stress conditions bind to high-affinity HSEs within their HSP70A and HSP82 target promoters, respectively (36,37,65–68). Hence, HSF1 as part of the putative scaffold is constitutively present at the A promoter. Second, downregulation of HSF1 or mutation of HSE1/2 or HSE4 impaired the activation effect on downstream promoters [(34); Figures 2, 3 and 6–8], thereby confirming the essential role of permanently bound HSF1 in the activation process. Third, mutation of the A promoter’s TATA-box, required for stabilizing TFIID binding (69), also impaired the activation effect of A promoter proximal and distal HSEs on downstream promoters [(34); Figures 2, 3 and 8]. The strong dependence of HSE4 on intact HSE1/2 and TATA-box (Figure 3) suggest that HSF1 binding to HSE4 most likely via loop formation cooperatively interacts with HSF1 and TFIID binding to the proximal A promoter.

Curiously, under non-stress conditions, transcription initiation from promoter fusions of the A promoter with R, CYC6, HSP70B or β2TUB promoters was found to always take place at the initiation site of the downstream promoter (15,31,32,34). If the scenario of a constitutively bound scaffold at the A promoter from which Pol II (re)initiation is driven is correct, why then does transcription initiation not occur at the A promoter’s transcriptional start site? And why is the rate of initiation at the downstream promoter higher than at the A promoter (15)? We speculate that, similar to the situation in yeast, subunits of mediator at the A promoter might serve to negatively regulate transcription elongation under non-inducing conditions (61,70). Alternatively, or in addition, transcription elongation might be impeded by the presence of a positioned nucleosome that hides the A promoter’s transcriptional start site (33). Either block might be overcome by factors contributed by the downstream promoters, like the initiator (Inr) sequence or the downstream promoter element (DPE) or proteins binding to them. In fact, TATA-box binding protein associated factors (a complex of TAFII250 and TAFII150) were shown to specifically interact with the Inr sequence and to determine basal promoter strength and responsiveness to activating signals (71). The latter might explain, why the A promoter acts as a transcriptional state enhancer, while the transcription rate is determined by the downstream R promoter (31,72).

HSF-mediated counteracting of gene silencing in Chlamydomonas and other organisms

Gene silencing via heterochromatin in Drosophila or via Tup1-Ssn6 in yeast is characterized by the occlusion of general transcription factors to their target sites (73,74). For example, the access of GAGA factor, TBP and Pol II to non-induced hsp26 and hsp70 promoters within heterochromatin of Drosophila is blocked (5). If silencing of transgene promoters in Chlamydomonas is similarly mediated by the occlusion of cis-regulatory elements, HSF1 in the context of the full-length A promoter apparently is able to overcome this block.

Interestingly, gene silencing mediated in yeast by the silent information regulator (Sir) at a transgenic HSP82 promoter does not block access of HSF1, TBP and Pol II, but a step downstream of transcription initiation (75). This block to a minor extent is overcome by heat shock. The same is true for a Polycomb-silenced transgenic hsp26 promoter in Drosophila (76). Obviously, HSFs in yeast and Drosophila cannot override Sir- and PcG-silencing, respectively, under non-stress conditions, and after heat shock can do so only to a limited extent. In contrast, HSF1 in Chlamydomonas can override the yet unknown silencing mechanism under non-stress conditions even at close by promoters. This is also reflected by the observation that yeast HSF1 constitutively binding to the Sir-silenced HSP82 promoter is not able to mediate local histone acetylation, whereas Chlamydomonas HSF1 is (75). These inter-species comparisons suggest that, no matter which silencing mechanism is at work at transgenic promoters in Chlamydomonas (occlusion of transcription factor binding sites or blocking a step downstream of transcriptional initiation), HSF1 in context of the A promoter seems to be particularly efficient in overriding it even under non-stress conditions.

In summary, we have gained many important insights into transcriptional transgene silencing in Chlamydomonas and why the A promoter to some extent is able to counteract this phenomenon. The hypothesis that HSF1 might organize a scaffold at the A promoter for Pol II recruitment to downstream promoters now allows the design of targeted experiments to test this idea and may provide entry points for the design of promoters that are more resistant to silencing.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Figures 1–4.

FUNDING

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [Schr 617/7-1 to M.S.]; Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Systems Biology Initiative FORSYS, project GoFORSYS); Max Planck Society. Funding for open access charge: Max Planck Society.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Kornberg RD. Eukaryotic transcriptional control. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:M46–M49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauria M, Rossi V. Epigenetic control of gene regulation in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1809:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cryderman DE, Tang H, Bell C, Gilmour DS, Wallrath LL. Heterochromatic silencing of Drosophila heat shock genes acts at the level of promoter potentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3364–3370. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dijk K, Marley KE, Jeong BR, Xu J, Hesson J, Cerny RL, Waterborg JH, Cerutti H. Monomethyl histone H3 lysine 4 as an epigenetic mark for silenced euchromatin in Chlamydomonas. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2439–2453. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterborg JH, Robertson AJ, Tatar DL, Borza CM, Davie JR. Histones of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Synthesis, acetylation, and methylation. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:393–407. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casas-Mollano JA, Jeong BR, Xu J, Moriyama H, Cerutti H. The MUT9p kinase phosphorylates histone H3 threonine 3 and is necessary for heritable epigenetic silencing in Chlamydomonas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6486–6491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711310105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruthenburg AJ, Wang W, Graybosch DM, Li H, Allis CD, Patel DJ, Verdine GL. Histone H3 recognition and presentation by the WDR5 module of the MLL1 complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Wu-Scharf D, Jeong BR, Cerutti H. A WD40-repeat containing protein, similar to a fungal co-repressor, is required for transcriptional gene silencing in Chlamydomonas. Plant J. 2002;31:25–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casas-Mollano JA, van Dijk K, Eisenhart J, Cerutti H. SET3p monomethylates histone H3 on lysine 9 and is required for the silencing of tandemly repeated transgenes in Chlamydomonas. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:939–950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaver S, Casas-Mollano JA, Cerny RL, Cerutti H. Origin of the polycomb repressive complex 2 and gene silencing by an E(z) homolog in the unicellular alga Chlamydomonas. Epigenetics. 2010;5:301–312. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.4.11608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamasaki T, Miyasaka H, Ohama T. Unstable RNAi effects through epigenetic silencing of an inverted repeat transgene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics. 2008;180:1927–1944. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.092395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki T, Ohama T. Involvement of Elongin C in the spread of repressive histone modifications. Plant J. 2011;65:51–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroda M, Blocker D, Beck CF. The HSP70A promoter as a tool for the improved expression of transgenes in Chlamydomonas. Plant J. 2000;21:121–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroda M, Vallon O, Wollman FA, Beck CF. A chloroplast-targeted heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) contributes to the photoprotection and repair of photosystem II during and after photoinhibition. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1165–1178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.6.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sizova I, Fuhrmann M, Hegemann P. A Streptomyces rimosus aphVIII gene coding for a new type phosphotransferase provides stable antibiotic resistance to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Gene. 2001;277:221–229. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00616-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lechtreck KF, Rostmann J, Grunow A. Analysis of Chlamydomonas SF-assemblin by GFP tagging and expression of antisense constructs. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:1511–1522. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfannenschmid F, Wimmer VC, Rios RM, Geimer S, Krockel U, Leiherer A, Haller K, Nemcova Y, Mages W. Chlamydomonas DIP13 and human NA14: a new class of proteins associated with microtubule structures is involved in cell division. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:1449–1462. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reisdorph NA, Small GD. The CPH1 gene of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii encodes two forms of cryptochrome whose levels are controlled by light-induced proteolysis. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1546–1554. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.031930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iliev D, Voytsekh O, Schmidt EM, Fiedler M, Nykytenko A, Mittag M. A heteromeric RNA-binding protein is involved in maintaining acrophase and period of the circadian clock. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:797–806. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heitzer M, Zschoernig B. Construction of modular tandem expression vectors for the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using the Cre/lox-system. Biotechniques. 2007;43 doi: 10.2144/000112556. 324, 326, 328 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J, Hu Z, Wang C, Li S, Lei A. Efficient expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) mediated by a chimeric promoter in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2008;26:242–247. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molnar A, Bassett A, Thuenemann E, Schwach F, Karkare S, Ossowski S, Weigel D, Baulcombe D. Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in the unicellular alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 2009;58:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoppmeier J, Mages W, Lechtreck KF. GFP as a tool for the analysis of proteins in the flagellar basal apparatus of Chlamydomonas. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2005;61:189–200. doi: 10.1002/cm.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meslet-Cladiere L, Vallon O. Novel shuttle markers for nuclear transformation of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell. 2011;10:1670–1678. doi: 10.1128/EC.05043-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamano T, Tsujikawa T, Hatano K, Ozawa S, Takahashi Y, Fukuzawa H. Light and low-CO2-dependent LCIB-LCIC complex localization in the chloroplast supports the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1453–1468. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li SS, Tsai HJ. Transgenic microalgae as a non-antibiotic bactericide producer to defend against bacterial pathogen infection in the fish digestive tract. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009;26:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen HL, Li SS, Huang R, Tsai HJ. Conditional production of a functional fish growth hormone in the transgenic line of Nannochloropsis oculata (Eustigmatophyceae) J. Phycol. 2008;44:768–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2008.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lumbreras V, Stevens DR, Purton S. Efficient foreign gene expression in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii mediated by an endogenous intron. Plant J. 1998;14:441–447. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroda M, Beck CF, Vallon O. Sequence elements within an HSP70 promoter counteract transcriptional transgene silencing in Chlamydomonas. Plant J. 2002;31:445–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Gromoff ED, Schroda M, Oster U, Beck CF. Identification of a plastid response element that acts as an enhancer within the Chlamydomonas HSP70A promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4767–4779. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lodha M, Schroda M. Analysis of chromatin structure in the control regions of the Chlamydomonas HSP70A and RBCS2 genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;59:501–513. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-0450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lodha M, Schulz-Raffelt M, Schroda M. A new assay for promoter analysis in Chlamydomonas reveals roles for heat shock elements and the TATA box in HSP70A promoter-mediated activation of transgene expression. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:172–176. doi: 10.1128/EC.00055-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merchant SS, Prochnik SE, Vallon O, Harris EH, Karpowicz SJ, Witman GB, Terry A, Salamov A, Fritz-Laylin LK, Marechal-Drouard L, et al. The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science. 2007;318:245–250. doi: 10.1126/science.1143609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz-Raffelt M, Lodha M, Schroda M. Heat shock factor 1 is a key regulator of the stress response in Chlamydomonas. Plant J. 2007;52:286–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strenkert D, Schmollinger S, Sommer F, Schulz-Raffelt M, Schroda M. Transcription factor dependent chromatin remodeling at heat shock and copper responsive promoters in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2285–2301. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.085266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris EH. The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook: Introduction to Chlamydomonas and Its Laboratory Use. 2nd edn. San Diego, CA: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kindle KL. High-frequency nuclear transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:1228–1232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimogawara K, Fujiwara S, Grossman A, Usuda H. High-efficiency transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by electroporation. Genetics. 1998;148:1821–1828. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berthold P, Schmitt R, Mages W. An engineered Streptomyces hygroscopicus aph 7” gene mediates dominant resistance against hygromycin B in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Protist. 2002;153:401–412. doi: 10.1078/14344610260450136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmollinger S, Strenkert D, Schroda M. An inducible artificial microRNA system for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii confirms a key role for heat shock factor 1 in regulating thermotolerance. Curr. Genet. 2010;56:383–389. doi: 10.1007/s00294-010-0304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kropat J, von Gromoff ED, Muller FW, Beck CF. Heat shock and light activation of a Chlamydomonas HSP70 gene are mediated by independent regulatory pathways. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1995;248:727–734. doi: 10.1007/BF02191713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schroda M, Vallon O, Whitelegge JP, Beck CF, Wollman FA. The chloroplastic GrpE homolog of Chlamydomonas: two isoforms generated by differential splicing. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2823–2839. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strenkert D, Schmollinger S, Schroda M. Protocol: methodology for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Methods. 2011;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nordhues A, Schottler MA, Unger AK, Geimer S, Schonfelder S, Schmollinger S, Rutgers M, Finazzi G, Soppa B, Sommer F, et al. Evidence for a role of VIPP1 in the structural organization of the photosynthetic apparatus in Chlamydomonas. Plant Cell. 2012;24:637–659. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petracek ME, Lefebvre PA, Silflow CD, Berman J. Chlamydomonas telomere sequences are A+T-rich but contain three consecutive G-C base pairs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:8222–8226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerutti H, Johnson AM, Gillham NW, Boynton JE. A eubacterial gene conferring spectinomycin resistance on Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: integration into the nuclear genome and gene expression. Genetics. 1997;145:97–110. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevens DR, Rochaix JD, Purton S. The bacterial phleomycin resistance gene ble as a dominant selectable marker in Chlamydomonas. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1996;251:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02174340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, Schreiber SL, Mellor J, Kouzarides T. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature. 2002;419:407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature01080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pokholok DK, Harbison CT, Levine S, Cole M, Hannett NM, Lee TI, Bell GW, Walker K, Rolfe PA, Herbolsheimer E, et al. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell. 2005;122:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim T, Buratowski S. Dimethylation of H3K4 by Set1 recruits the Set3 histone deacetylase complex to 5' transcribed regions. Cell. 2009;137:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation patterns in higher eukaryotic genes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:73–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waterborg JH. Dynamics of histone acetylation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27602–27609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allamane S, Jourdes P, Ratel D, Vicat JM, Dupre I, Laine M, Berger F, Benabid AL, Wion D. Bacterial DNA methylation and gene transfer efficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;276:1261–1264. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakurai H, Enoki Y. Novel aspects of heat shock factors: DNA recognition, chromatin modulation and gene expression. FEBS J. 2010;277:4140–4149. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]