Abstract

Objective

To estimate the aggregate burden of maternal binge drinking on preterm birth (PTB) and low birth weight (LBW) across American sociodemographic groups in 2008.

Methods

A simulation model was developed to estimate the number of PTB and LBW cases due to maternal binge drinking. Data inputs for the model included number of births and rates of preterm and LBW from the National Center for Health Statistics; female population by childbearing age groups from the U.S. Census; increased relative risks of preterm and LBW deliveries due to maternal binge drinking extracted from the literature; and adjusted prevalence of binge drinking among pregnant women estimated in a multivariate logistic regression model using Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.

Results

The most conservative estimates attributed maternal binge drinking to 8,701 (95% CI: 7,804–9,598) PTBs (1.75% of all PTBs) and 5,627 (95% CI 5,121–6,133) LBW deliveries in 2008, with 3,708 (95% CI: 3,375–4,041) cases of both PTB and LBW. The estimated rate of PTB due to maternal binge drinking was 1.57% among all PTBs to White women, 0.69% among Black women, 3.31% among Hispanic women, and 2.35% among other races. Compared to other age groups, women ages 40–44 had the highest adjusted binge drinking rate and highest PTB rate due to maternal binge drinking (4.33%).

Conclusion

Maternal binge drinking contributed significantly to PTB and LBW differentially across sociodemographic groups.

Keywords: Maternal binge drinking, Preterm birth, Low birth weight, Racial/ethnic disparities, Simulation

Introduction

Heavy drinking by pregnant women is associated with a range of adverse consequences to the developing fetus. The most studied adverse outcome is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). When infants exposed to alcohol prenatally do not meet the criteria of diagnosis of FAS, there are still significant short and long-term impacts on behavioral and cognitive development, usually classified as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs) [1,2]. Research indicates that approximately 1–3% of all children born in the U.S. are affected by alcohol [3]. About 130,000 pregnant women each year drink at levels that significantly increase the risk of having a child with FASD [4].

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as gestational age of <37 completed weeks, is a growing public health problem. Preterm infants have a higher risk of short and long-term health complications [5–8] compared to babies born near term. The U.S. PTB rate rose by more than one-third from the early 1980s through 2006 and despite a moderate decline thereafter, remained at 12.3% in 2008 [9–11]. A high overlap in preterm and low birth weight (LBW, defined as <2,500 grams) deliveries exists. Hence, U.S. trends in LBW incidence are similar to that of preterm, reaching 8.1% of live births in 2008 [9]. Persistent disparities in PTB and LBW among different race/ethnicity groups are a public concern [7,12]. Risk factors for PTB and LBW are multiple, including biological, behavioral, and psychosocial effects; medical and pregnancy conditions; role of gene-environment interactions; and unfavorable sociodemographic and community characteristics [7].

Alcohol misuse is a leading risk factor for many adverse health and social outcomes [13]. Heavy drinking by pregnant women is associated with adverse consequences particularly harmful to the fetus [14–18]. Prenatal alcohol exposure has been found to result in restricted growth of the fetus, prematurity, and LBW [8, 19–21].

Research shows that the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure follows a dose-response curve related to the frequency and amount of consumption during pregnancy [22, 23]. Early studies found that only women with high alcohol consumption levels (e.g., ≥5 drinks per occasion at least once a week) had elevated odds for preterm delivery [24, 25]. Later studies found that the relationship between PTB and various levels of alcohol consumption followed a J-shaped curve [8, 21, 26–29], where low levels (e.g., 1–2 drinks/week) of alcohol consumption had no effect on PTB. As alcohol consumption increased past certain thresholds (≥10 drinks/week [27]), the risk of PTB increased. Another study found that prenatal alcohol consumption was associated with elevated risk for PTB even with consumption of 1–2 drinks/week [30]. Studies have found a similar dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and LBW [31–34]. While the exact effect of maternal drinking on PTB and LBW is not known, it is has been explained as a result of elevated levels of prostaglandins in the fetal tissues, which contribute to the initiation and progression of labor [30, 35–38].

The Institute of Medicine acknowledged “a lack of progress in understanding causes and prevention” of PTB [7]. Little is known about how much each risk factor contributed to the total burden of PTB and LBW. This study focuses on one particular risk factor that has been attributed to PTB and LBW in individual studies: maternal binge drinking. We attempted to aggregate the problem to the national scale by estimating the magnitude and distribution of PTB and LBW across race and age groups in the U.S. as a result of maternal binge drinking.

Methods

Conceptually, the burden of PTB or LBW due to maternal binge drinking is the difference between the number of PTB/LBW cases due to all causes in the real world and the number of cases in a hypothetical world free of maternal binge drinking, ceteris paribus. In order to estimate the number of PTB or LBW due to maternal binge drinking, we performed four major tasks (to be further explained below): conducting a systematic literature review; preparing data; estimating the adjusted prevalence of maternal binge drinking across sociodemographic groups; and developing a simulation model that “counts” the number of PTB/LBW cases due to maternal binge drinking under different scenarios.

Systematic literature review

The primary purpose of the systematic review was to determine if sufficient evidence exists of the causal relationship between maternal drinking and PTB and LBW. To identify relevant studies, the initial inclusion criteria were that the study was (i) published in English in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii) included relevant definitions and measures of maternal drinking, prematurity, and LBW; (iii) controlled for confounding factors; (iv) reported quantitative results; and (v) studied a population in a developed country.

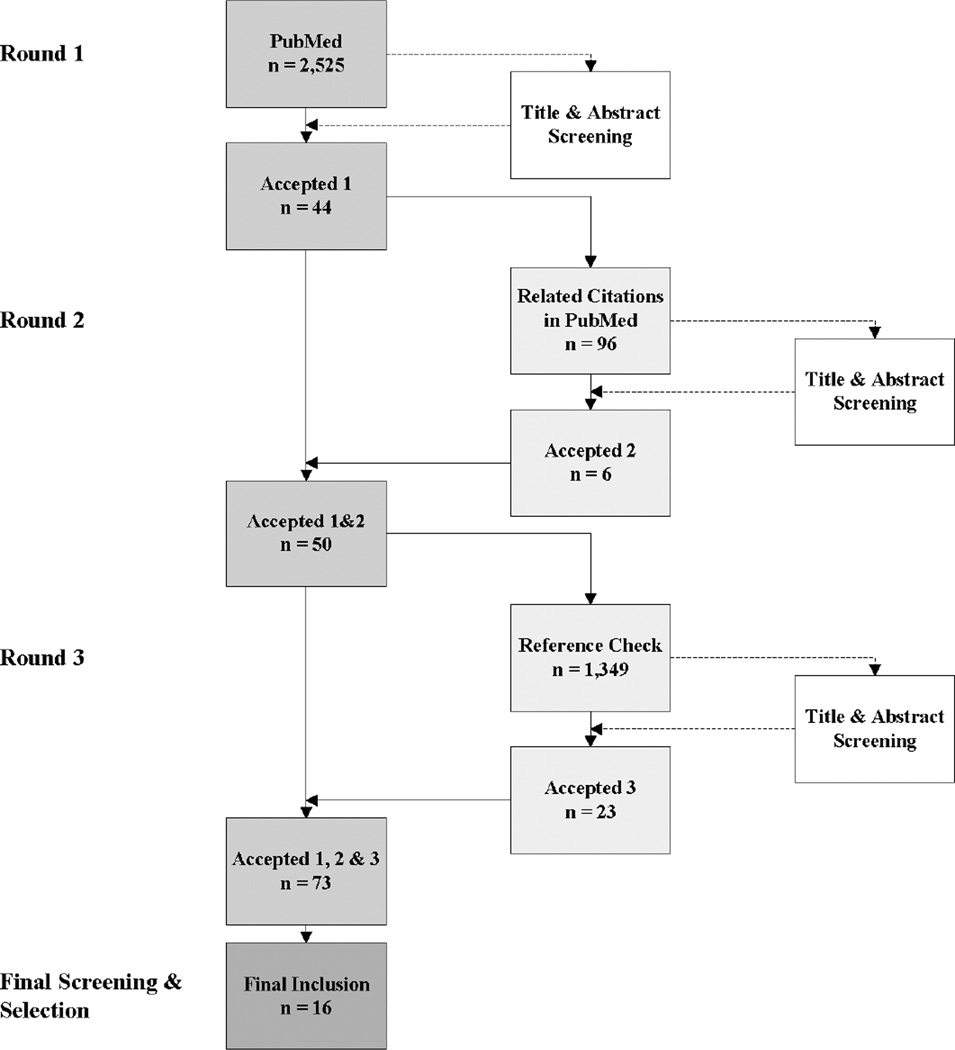

Our key word selections were based on the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), which has a hierarchical structure with definitions of each entry item and the equivalent entry terms, thus providing a convenient way for retrieving studies that may use different terminologies for the same concept. The search was conducted in three rounds (see Figure 1). In round one, we searched in PubMed using broad key search terms, resulting in 2,525 studies. After screening by title and abstract, 44 studies were kept. Round two reviewed “Related Citations” in PubMed and found 6 additional articles. In round three, the references of each of the 50 initially accepted papers were checked and 23 more studies were found. Final screening involved reading full texts, considering strengths and weaknesses of each study, and debating among the research team. Sixteen articles were selected to extract the quantitative results for our analyses [8, 25–30, 33, 39–46]. The search was conducted during June–August of 2011.

Figure 1.

Systematic review flowchart

The systematic review provided sufficient evidence that prenatal alcohol elevated the risk for PTB and LBW. However, with regard to the effect size, there is no uniform conclusion across studies due to large heterogeneity in study designs, data samples, dose and timing of prenatal alcohol exposure, confounding factors, and other issues. Formal meta-analysis techniques could not be used to obtain a precise estimate of the magnitudes of the effect. We therefore used a range of estimated increased risks of PTB and LBW. Risks of PTB and LBW reported in odd ratios (ORs) were converted into relative risks (RRs) [47].

Data

To estimate the prevalence of maternal binge drinking, we used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which is an annual cross-sectional telephone survey, including various questions about alcohol use behaviors in the past 30 days and pregnancy status. Since BRFSS included only adults aged 18 and above, we used data from the Monitoring the Future survey [48] to account for binge drinking among girls ages 15–17. We then used data from the National Center for Health Statistics and Census [49] for the number of live births and number of women ages 15–44. Numbers and rates of PTB and LBW due to all causes were obtained from a National Vital Statistics Report [50]. Lastly, the range of RRs of PTB and LBW due to maternal drinking came from the literature.

Estimation of adjusted prevalence of maternal binge drinking

Though we aimed to estimate the burden of maternal drinking for 2008, 4 years of BRFSS data (2006–2009) were combined to increase the sample size and improve the precision of estimates when stratifying by race/ethnicity and age cohorts. Data before 2006 could not be used as the definition of binge drinking among women in BRFSS changed from five drinks in the early years to four drinks in 2006. The analytic sample included 11,500 pregnant women ages 18–44. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to estimate the adjusted drinking prevalence. The dependent variable was a binary measure of binge drinking, defined as consuming ≥4 drinks on an occasion during the past 30 days. The explanatory variables included education levels (no high school, high school, some college, college), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), age group (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44), income levels (high, middle, low), marital status (married or member of an unmarried couple versus other), employment status (working for wages or self-employed versus other), smoking (current smokers versus other), and state of residency (to control for changing survey participation by states over time).

To generalize the findings to the overall population, sampling weights were used to adjust for differences in the probability of selection of respondents in each survey population attributable to the sampling design and for differential response rates among sub-populations. Statistical estimations were conducted in Stata 11.0.

Simulation model

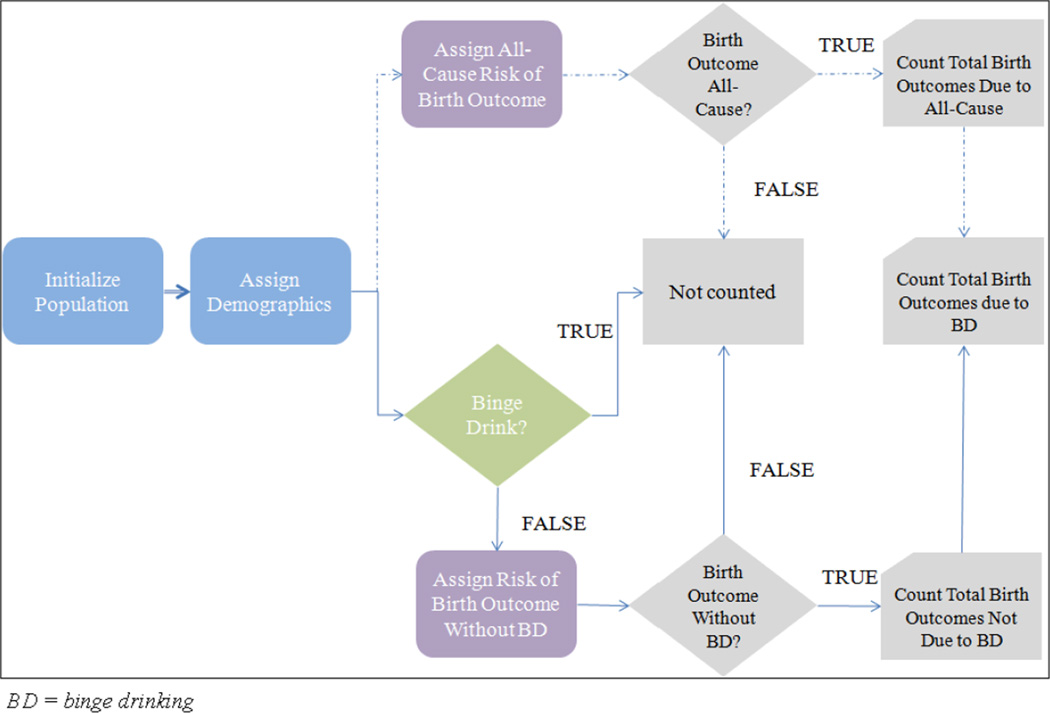

A simulation model was developed to estimate the total number of birth outcomes (PTB or LBW) due to maternal binge drinking in the U.S. population. The simulation flow is depicted in Figure 2. The simulation begins with an initial population, composed of births from women ages 18–44 in 2008. Each birth is assigned two demographic attributes, race/ethnicity and the mother’s age cohort (we assume that the mother’s race is the same as the infant). The race/ethnicity groups include non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Other. The age cohorts are 18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39 and 40–44. This initial path is represented by the bold line in Figure 2. At this point, each birth takes two paths. The top path, represented by the dashed line, is independent of maternal drinking behavior. Each birth is assigned an “All-Cause” risk of a birth outcome (PTB/LBW due to all causes) which can be stratified by race/ethnicity or age cohort. Each realized birth outcome due to “All-Cause” is added to a counter. The bottom path, represented by the solid line, considers maternal binge drinking behavior. For each birth, the simulation determines whether the mother participated in binge drinking, and the likelihood of this event depends on the mother’s race/ethnicity and age, adjusted for other factors (explained in the regression model). If the mother does not binge drink, the birth is assigned a risk of a birth outcome “Without BD” (PTB/LBW due to all causes except binge drinking). Having obtained the prevalence of PTB/LBW due to all causes, prevalence of maternal binge drinking, and increased risk of PTB/LBW due to maternal binge drinking, the probability of PTB/LBW without binge drinking was estimated using Bayes rule. Each realized birth outcome “Without BD” is added to a counter. Because the literature review provided a range of the increased risks of PTB and LBW as consequences of maternal binge drinking, different thresholds of elevated risks were used in the simulation model. The total number of birth outcomes due to binge drinking is computed by taking the difference of the two counters.

Figure 2.

Simulation model schematic

Model variability comes from two sources. First, the patient attributes and PTB/LBW all-cause probabilities are drawn from discrete distributions. Secondly, the 95% confidence interval (CI) around the adjusted prevalence of maternal binge drinking is estimated from a statistical model (described above). The adjusted prevalence is a sample mean and its sampling distribution is normally distributed given the sample size. In the simulation, the same birth progresses through both paths, thus the same random number stream is used to generate the patient attributes, thereby eliminating any variance attributable to different patient characteristics. This technique results in tighter confidence intervals around the output (number of PTB/LBW) [51]. The model was implemented using Rockwell’s simulation software Arena 13.5.

Sensitivity analyses

BRFSS is a telephone-based survey that relies on self-reports. Alcohol use, especially binge drinking during pregnancy, is subject to recall and social desirability response biases [52–54]. The sensitivity analysis included two assumed levels of under-report (20% and 50%) of binge drinking during pregnancy at two thresholds of RRs (1.2 and 1.5). BRFSS only covers adults, thus missing girls ages 15–17. Using data from Monitoring the Future [50], we estimated the prevalence of binge drinking rate among young girls and its impact on PTB and LBW deliveries.

Results

Table 1 presents data from all sources. Panel A.1 shows the number of live births (singleton and multiple) to women ages 18–44 in 2008 by the mother’s age cohort and the infant’s race/ethnicity. Panel A.2 shows the stratified rates of PTB due to all causes in 2008. Non-Hispanic Black women experienced the highest rate of PTB, 17.4%, compared to 11.1% among non-Hispanic White women. Panel A.3 presents the adjusted prevalence of binge drinking by race/ethnicity and age cohort. After adjusting for the other characteristics specified in the regression model, the prevalence of binge drinking was highest among Hispanic women, 2.8%, compared to the lowest prevalence of 0.6% among non-Hispanic Black women. Maternal binge drinking was most prevalent among women ages 40–44 (3.8%). Panels A.4 and A.5 show the extracted range of adjusted RRs of PTB (1.2–2.0) and LBW (1.3–1.9), respectively, due to binge drinking and the RRs converted from ORs. A study published after the systematic review was completed supports our range of RR for PTB [55]. Converted RRs from this study were 1.7 (for 3–4 alcoholic drinks/week) and 1.9 (for ≥5 alcoholic drinks/week). Panel B provides the input measures for our sensitivity analysis of women ages 15–17. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the analytic sample from BRFSS which included 11,500 pregnant women ages 18–44. The unadjusted rate of binge drinking is 1.3% among all pregnant women.

Table 1.

Simulation model inputs of childbearing women in 2008

| A. AGES 18–44 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.1 Number of live birthsa | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Black, non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Other | All Races and Ages | |

| 2,219,018 | 585,436 | 984,876 | 277,783 | ||

| Age 18–24 | Age 25–29 | Age 30–34 | Age 35–39 | Age 40–44 | |

| 1,342,457 | 1,187,295 | 948,904 | 483,876 | 104,581 | 4,067,113 |

| A.2 Rate of preterm birth due to all causesb | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Black, non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Other | All Races | |

| Age 18–24 | 11.1% | 16.8% | 11.7% | 12.2% | 12.5% |

| Age 25–29 | 10.3% | 16.9% | 11.1% | 10.9% | 11.4% |

| Age 30–34 | 10.8% | 17.8% | 12.1% | 9.8% | 11.7% |

| Age 35–39 | 12.6% | 20.3% | 14.3% | 12.1% | 13.7% |

| Age 40–44 | 15.0% | 22.4% | 16.9% | 15.4% | 16.3% |

| All Ages | 11.1% | 17.4% | 12.0% | 11.2% | 12.2% |

| A.3 Adjusted prevalence of maternal binge drinkingc | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Black, non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Other | All Races and Ages | |

| 1.4% | 0.6% | 2.8% | 1.9% | ||

| Age 18–24 | Age 25–29 | Age 30–34 | Age 35–39 | Age 40–44 | |

| 1.5% | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 3.8% | 1.3% |

| A.4 Increased risks of preterm birth due to maternal binge drinking | |||||

| Selected thresholds of RRsd: 1.2 1.5 1.7 2.0 | |||||

| Converting ORs into RRse (Control Risk = 10.8%): | |||||

| Classification of drinker | Adjusted OR | Converted RR | |||

| All drinkers | 1.32 | 1.27 | |||

| Class 1 (1–2 drinks/week) | 1.14 | 1.12 | |||

| Class 2 (3–4 drinks/week) | 1.86 | 1.70 | |||

| Class 3 (>5 drinks/week) | 2.25 | 1.98 | |||

| A.5 LBW | |||||

| Rate of LBW due to all causesf: 8.1% | |||||

| Percent of LBW babies that are pretermf: 65.9% | |||||

| Selected thresholds of RR due to maternal binge drinkingg: 1.3 1.5 1.7 1.9 | |||||

| B. AGES 15–17 | |||||

| Number of live birthsa: | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Black, non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Other | All races | |

| 43,028 | 34,737 | 52,818 | 5,126 | 135,709 | |

| Rate of preterm birth due to all causesb: 14.1% | |||||

| Prevalence of maternal binge drinkingh: 21.5% | |||||

CI = confidence interval, RR = relative risk, OR = odds ratio, LBW = low birth weight

CDC/NCHS (2010), Table 6, p.30–31.

CDC/NCHS (2010), Table 25, p.61–62.

Obtained from a logistic multivariate regression model using BRFSS. Binge drinking was adjusted for educational attainment, income levels, ages (or race/ethnicity), employment, marital status, and smoking behavior.

Range of RRs came from the literature (Borges et al., 1993; Lazzaroni et al, 1993; Kesmodel et al., 2000; Parazzini et al., 2003; Albertsen et al., 2004; O’Leary et al., 2009; Aliyu et al., 2010; Berkowitz et al., 1982; Henderson et al., 2007; Kilduff et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2005; Peacock et al., 1995; Savitz & Murnane, 2010). RRs in selected studies were typically adjusted for age, previous preterm delivery, parity, smoking during pregnancy, coffee consumption during pregnancy, and occupational status in the household.

Adjusted ORs came from Aliyu et al. (2010), converted into RRs following Zhang & Yu (1998). ORs were adjusted for maternal age, parity, race, smoking, education, marital status, adequacy of prenatal care, maternal height, gender of the infant, and year of birth.

Data source: CDC/NCHS (2010).

Range of RRs came from the literature. Adjusted ORs from Lazzaroni et al. (1993), Windham et al. (1995), Mariscal et al. (2006), and Jaddoe et al. (2007) were converted to RR (Zhang & Yu, 1998) using a control risk of 7.2%.

Monitoring the Future (Johnston et al., 2011)

Table 2.

Sample characteristics: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

| Pregnant Women | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. |

| No high school | 0.138 | 0.344 |

| High school | 0.246 | 0.431 |

| Some college | 0.230 | 0.421 |

| At least a college degree | 0.386 | 0.487 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 0.599 | 0.490 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.099 | 0.299 |

| Hispanic (any race) | 0.222 | 0.415 |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 0.080 | 0.272 |

| Ages 18–24 | 0.315 | 0.465 |

| Ages 25–29 | 0.270 | 0.444 |

| Ages 30–34 | 0.276 | 0.447 |

| Ages 35–39 | 0.106 | 0.307 |

| Ages 40–44 | 0.033 | 0.178 |

| Married | 0.771 | 0.420 |

| Working | 0.542 | 0.498 |

| Smoking | 0.069 | 0.254 |

| Any alcohol use | 0.076 | 0.264 |

| Binge drinkingb | ||

| +All races | 0.013 | 0.115 |

| +White, non-Hispanic | 0.014 | 0.116 |

| +Black, non-Hispanic | 0.013 | 0.115 |

| +Hispanic (any race) | 0.022 | 0.146 |

| +Other race, non-Hispanic | 0.019 | 0.137 |

Statistics are weighted to represent the U.S. population.

Sample included 11,500 pregnant women ages 18–44.

Defined as ≥4 drinks on at least one occasion in the past 30 days.

Table 3 presents results from the multivariate logistic regression model. This is the base model that is used to estimate the adjusted prevalence of binge drinking discussed previously. Hispanic women are most likely to binge-drink compared to other race groups after adjusting for age, education, income, marital status, smoking, and employment status.

Table 3.

Results of multivariate logistic regression

| Binge drinking | Odds Ratio | Std. Err. | z | P>|z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school | 1.02 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| Some college | 0.72 | 0.38 | −0.61 | 0.54 |

| College | 1.10 | 0.64 | 0.17 | 0.86 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.42 | 0.18 | −2.02 | 0.04 |

| Hispanic | 2.03 | 0.59 | 2.41 | 0.02 |

| Other race | 1.30 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.59 |

| Age 25–29 | 0.87 | 0.25 | −0.49 | 0.62 |

| Age 30–34 | 1.06 | 0.59 | 0.11 | 0.91 |

| Age 35–39 | 0.76 | 0.46 | −0.46 | 0.64 |

| Age 40–44 | 2.62 | 1.72 | 1.47 | 0.14 |

| Married/In partnership | 0.56 | 0.20 | −1.62 | 0.11 |

| Employed | 3.24 | 1.07 | 3.55 | 0.00 |

| Mid income | 2.27 | 1.23 | 1.51 | 0.13 |

| High income | 1.33 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| Smoking | 5.09 | 2.41 | 3.44 | 0.00 |

Reference groups: No high school for education; Non-Hispanic whites for race; Age 18–24 for age groups; Lowest income for income groups. Regression is weighted.

Simulation results

The simulation was initiated with 4,067,113 live births (see Table 1.A.1). We ran the simulation using various RRs of PTB (1.2, 1.5, 1.7, 2.0); results were stratified by race/ethnicity and age cohort. Next, estimates were made using different levels of RR of LBW (1.3, 1.5, 1.7, 1.9) while holding RR of PTB at 1.2. Each scenario ran for 10 replications and 95% CIs on the mean of the 10 replications were computed. Table 4 presents the main results of our analysis. Among the estimate of 496,775 PTBs to women ages 18–44 in 2008, 8,701±897 cases (1.75%) were attributed to maternal binge drinking under the most conservative RR (1.2). For less conservative RRs (1.5, 1.7, 2.0) the numbers are 10,710±897 (2.16%); 11,904±909 (2.40%); and 13,910±904 (2.80%).

Table 4.

Estimated number of preterm births from the simulation

| Due to All Causes | Due to Binge Drinking | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | Estimated [95% CI] | RR=1.2 | RR=1.5 | RR=1.7 | RR=2.0 | |

| All Races and Ages | 497,135 | 496,775 [496,389–497,161] | 8,701 (1.75%) | 10,710 (2.16%) | 11,904 (2.40%) | 13,910 (2.80%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 246,142 | 245,906 [245,627–246,186] | 3,859 (1.57%) | 4,949 (2.01%) | 5,608 (2.28%) | 6,708 (2.73%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 102,066 | 101,968 [101,831–102,104] | 699 (0.69%) | 876 (0.86%) | 993 (0.97%) | 1,160 (1.14%) |

| Hispanic | 117,920 | 117,880 [117,542–118,217] | 3,904 (3.31%) | 4,858 (4.12%) | 5,526 (4.69%) | 6,481 (5.50%) |

| Other race | 31,007 | 31,022 [30,920–31,123] | 730 (2.35%) | 894 (2.88%) | 1,005 (3.24%) | 1,170 (3.77%) |

CI = confidence interval, RR = relative risk

Parentheses denote rate of preterm due to binge drinking (calculated by dividing the estimated number due to binge drinking by the estimated number due to all causes).

Next, we consider the distribution of PTBs due to maternal binge drinking across race/ethnicity groups. Under RR of 1.2, of 245,906±279 PTBs to non-Hispanic White women, 3,859±466 cases (1.57%) were attributed to maternal binge drinking. PTB due to maternal binge drinking was 0.69% among PTBs to non-Hispanic Black women, 3.31% among Hispanic women, and 2.35% among women of other races. Table 4 provides more details on results stratified by race/ethnicity.

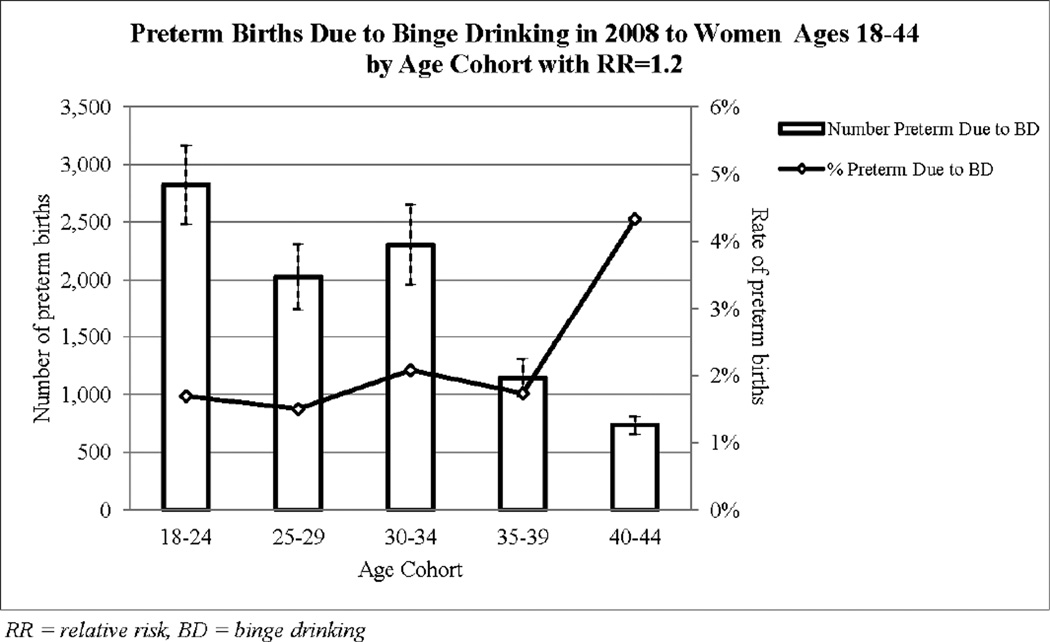

Figure 3 shows the estimated number of PTBs (bars with 95% CIs) and the rate of PTB (line graph) due to binge drinking in 2008 to women ages 18–44 by age cohort for RR of 1.2. Women ages 18–24 had the highest number of all-cause PTBs (167,227±278) of which 2,825±340 cases were attributed to alcohol use at binge levels. Women ages 40–44 had the smallest number of PTBs (736±77) but the highest rate (4.33%) due to binge drinking. The distribution of PTBs across age cohorts for less conservative RRs is similar to that in Figure 3. While births from those ages <17 and >45 were excluded in our main analysis, this exclusion does not substantially affect the estimated numbers because women ages >45 had a very low birth rate (0.7 per 1000 for those 45–54 with only 7,666 births in 2008) and inclusion of girls ages <17 only changes the number marginally as shown in the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 3.

Estimated number and rate of preterm births from the simulation by age cohort

It is important to validate our estimated numbers. Table 4 also shows the actual numbers of PTBs in the U.S. due to all causes at the population level and by race/ethnicity. As shown, the 95% CIs around our estimates capture the actual numbers of PTBs at the population level and within each race/ethnicity group (and additionally by age cohort but not shown in Table 4). We also validated the number of all-cause LBW cases (actual=329,910; estimated=330,002±348).

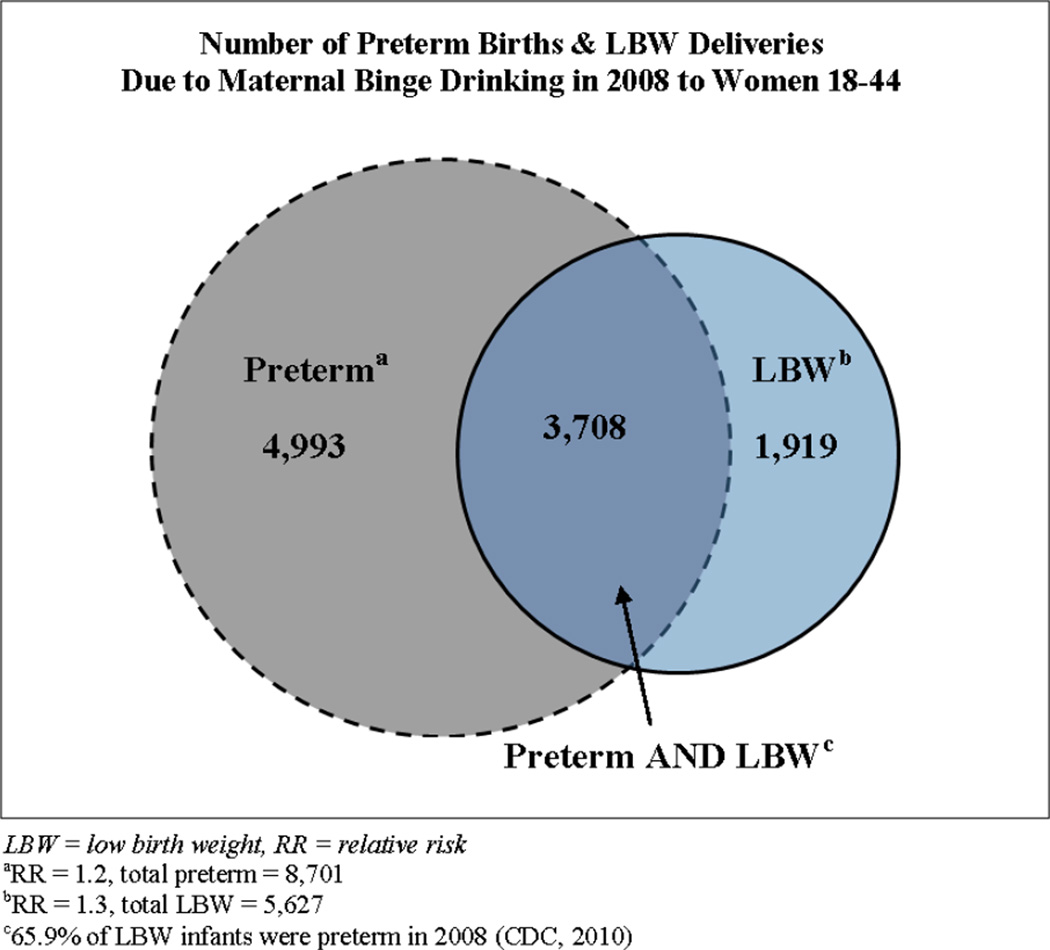

Regarding the impact of maternal binge drinking on LBW, our analysis estimates 330,002±348 cases of LBW due to all causes. The most conservative estimate (LBW RR=1.3) results in 5,627±506 LBW cases or 1.71% of all LBW cases attributable to maternal binge drinking (Figure 4). For less conservative RRs for LBW (1.5, 1.7, 1.9) the estimated number of LBW cases due to binge drinking were 6,438±509, 7,636±496, and 8,429±504. Additionally, the number of LBW infants who were also preterm due to all causes was 217,472±230. An estimated 3,708±333 cases of both PTB and LBW were due to maternal binge drinking for the most conservative RRs (LBW RR=1.3, PTB RR=1.2; Figure 4). An estimated 4,243±336, 5,032±326, and 5,555±332 cases of both PTB and LBW were due to binge drinking during pregnancy for LBW RR of 1.5, 1.7, and 1.9, respectively.

Figure 4.

Estimated number of preterm and LBW deliveries from the simulation

Sensitivity analysis results

Under-report of binge drinking during pregnancy was considered in a sensitivity analysis. As shown in Table 5, the two lower RRs of PTB (1.2, 1.5) were used in two scenarios, 20% and 50% under-report of binge drinking during pregnancy. In the 20% under-report scenarios, there is no statistically significant change in the estimated number of PTBs. Base-case estimates were 8,701±898 (RR=1.2) and 10,710±897 (RR=1.5) compared to 9,947±508 (RR=1.2) and 11,965±513 (RR=1.5) at 20% under-report. In the 50% under-report scenario, the estimated number of PTBs increased to 15,169±651 (RR=1.2) and 17,132±625 (RR=1.5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis results for under-report

| RR=1.2 | RR=1.5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of under-report | None | 20% | 50% | None | 20% | 50% |

| Number of preterm births [95% CI] | 8701 [7,803–9,599] | 9947 [9,439–10,455] | 15,169 [14,518–15,820] | 10,710 [9,813–11,607] | 11,965 [11,452–12,478] | 17,132 [16,507–17,757] |

| Increasea | 6,468 | 6,422 | ||||

RR = relative risk, CI = confidence interval

Under-report (20% or 50%) minus no under-report

To capture the impact of maternal binge drinking by women ages 15–17, we obtain Census estimates for the total number of women of all races ages 15–17 and corresponding number of live births in 2008 as 6,304,328 [48] and 135,709 [49], respectively. This corresponds to a birth rate of 21.5 per 1000. We use the all-cause PTB rate of 14.1% as reported for women ages ≤20 [11]. For this age group we cannot use BRFSS to estimate the adjusted prevalence of maternal binge drinking. However, the prevalence of binge drinking among senior girls according to Monitoring the Future [48] is 21.5%. If we assume that of those who binge drink, the same proportion binge drink while pregnant as 18–24 year olds as derived from BRFSS, we obtain 1.40% as the prevalence of maternal binge drinking among girls ages 15–17. With these estimates the simulation shows that 307±104 PTBs are due to maternal binge drinking, assuming the most conservative RR (1.2). If we assume that girls 15–17 are less likely to be aware of being pregnant and that among those who binge drink, the proportion of those that binge drink while pregnant is twice that of 18–24 year olds (resulting in a prevalence of maternal binge drinking of 2.8%), then an estimated 359±100 PTBs are due to maternal binge drinking.

Discussion

Maternal binge drinking is a cause of many adverse birth outcomes and fetal health problems [1,2]. To our knowledge, this is the first study that attempts to quantify the magnitude of PTB and LBW related to binge drinking during pregnancy. We found that maternal binge drinking accounted for a large proportion of PTB differentially across sociodemographic groups. Non-Hispanic black women had the highest PTB rate (17.4%) but the lowest maternal binge drinking rate (0.6%) and lowest rate of PTB due to maternal drinking (0.69% for RR=1.2). This finding is somewhat surprising as recent research suggests that differences in drinking cessation between black and white women who become pregnant partially explain the disparity in fetal alcohol syndrome rates: White women are more likely to reduce or quit their drinking when pregnant [56,57]. Hispanic women, contrarily, had the highest maternal binge drinking rate (2.8%) and highest rate of PTB due to maternal binge drinking (3.31% for RR=1.2). This finding is different from that of a recent study that estimated alcohol use among pregnant and non-pregnant women of childbearing age using BRFSS data from 1991–2005 where the rates were not significantly different between Whites and Hispanics [58]. One possible explanation is that our study used data from 2006–2009 when the definition of binge drinking changed from 5 to 4 drinks per occasion for women. It is also possible that there has been a change in drinking behaviors among pregnant women in these two race/ethnicity groups. Our findings are, however, in agreement with another study that finds Hispanic women are less likely to quit drinking while pregnant [57]. Compared to other age cohorts, women ages 40–44 had the highest adjusted binge drinking rate (3.8%) and highest PTB rate due to maternal drinking (4.33% for RR=1.2). Interestingly, inclusion of younger women ages 15–17 does not considerably impact the total number of PTBs due to binge drinking. This is not to say that binge drinking is not an issue among this age group. This lack of impact may reflect only the two particular health outcomes examined in this study and the preterm and low birth rates among this age cohort.

Our study is subject to limitations. First, the validity of our estimates depends on the quality of previous studies’ estimation. Second, the data samples in the selected studies from the literature may not represent the U.S. population. Third, we considered only binge drinking behavior. Birth outcomes, including PTB and LBW, depend on the intensity and duration of alcohol use at various stages of pregnancy. Different studies used different measures of maternal drinking. Thus, some of the RRs chosen were associated with lower levels of drinking or drinking level was not specified in detail. Looking at a range of RRs helped to account for some of this variability. We felt that adopting one drinking measure is necessary for the already complex estimation task. Fourth, biases in self-reporting of alcohol use during pregnancy are probably differential across socio-demographic groups; however, no prior study to provide possible differential levels of underreporting was available. We adopted uniform levels of under-reports for all sociodemographic groups. Results from the sensitivity analysis, assuming 20% under-report of binge drinking, do not statistically change the estimates; thus, differential under-report levels would be unlikely to affect our estimates.

One in eight babies is born too soon in the U.S. [59]. Quantification of the effect of maternal drinking is an important step in deciding how to plan and target services to the subpopulation most in need. Further studies to estimate burden of other risk factors on PTB and LBW are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant R21AA017265) and National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant 1R01MD004251-01). Additional funding was provided by an internal grant from College of Health, Education and Human Development at Clemson University.

Footnotes

We have no conflicts of interest relating to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. [Last accessed on 05/16/2012]; http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/index.html.

- 3.Mengel M, Searight H, Cook K. Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies. JABFM. 2006;9(5):494–505. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. 2004 Aug; Preventing Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/fasprev.htm.

- 5.Slattery MM, Morrison JJ. Preterm delivery. Lancet. 2002;360(9344):1489–1497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews TJ, Menacker F, MacDoman MF. National Vital Statistics Reports. 12. Vol. 50. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2000 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Sets. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behrman RE, Butler AS. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Leary C, Nassar N, Kurinczuk J, Bower C. The effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth and preterm birth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2009;116(3):390–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics Reports, Births: Final Data for 2008. 2010 Dec;Vol. 59(No. 1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S, Mathews TJ. National vital statistics reports. no 7. vol 57. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Births: Final data for 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin JA, Osterm an MJK, Sutton PD. NCSH data brief. no. 39. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. Are preterm births on the decline in the United States? Recent data from the National Vital Statistics System. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparks PJ. Do biological, sociodemographic, and behavioral characteristics explain racial/ethnic disparities in preterm births? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1667–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Tenth special report to the U.S. Congress on alcohol and health. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodlett CR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: new perspectives on diagnosis and intervention. Alcohol. 2010;44:579–582. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, Nordstrom B. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2003;290(22):2996–2999. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chudley A, Conry J, Cook J, Loock C, Rosales T, LeBlanc N. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMJA. 2005;172(5):S2–S21. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calhoun F, Warren K. Fetal alcohol syndrome: Historical perspectives. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;31:168–171. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley EP, Guerri C, Calhoun F, Charness ME, Foroud TM, Li T, Mattson SN, May PA, Warren KR. Prenatal alcohol exposure: Advancing knowledge through international collaborations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):118–135. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000047351.03586.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aliyu MH, Wilson RE, Zoorob R, Brown K, Alio AP, Clayton H, Saihu H. Prenatal alcohol consumption and fetal growth restriction: potentiation effect by concomitant smoking. Nitcotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11(1):36–43. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, Chatenoud L, Ricci E, Sandretti F, Cipriani S, Caserta D, Fedele L. Alcohol drinking and risk of small for gestational age birth. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(9):1062–1066. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602419. Epub 2006 Feb 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokol RJ, Janisse JJ, Louis JM, Bailey BN, Ager J, Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL. Extreme prematurity: An alcohol-related birth effect. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(6):1031–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carr J, Agnihotri S, Keightley M. Sensory processing and adaptive behavior deficits of children across the fetal alcohol spectrum disorder continuum. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(6):1022–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sood B, Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Nordstrom-Klee B, Ager J, Templin T, Janisse J, Martier S, Sokol R. Prenatal alcohol exposure and childhood behavior at age 6 to 7 years: I. dose-response effect. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E34. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald AD, Armstrong BG, Sloan M. Cigarette, alcohol, and coffee consumption and prematurity. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(1):87. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borges G, Lopez-Cervantes M, Medina-Mora ME, Tapia-Conyer R, Garrido F. Alcohol consumption, low birth weight, and preterm delivery in the national addiction survey (Mexico) Subst Use Misuse. 1993;28(4):355–368. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazzaroni F, Bonassi S, Magnani M, Calvi A, Repetto E, Serra G, Podesta F, Pearce N. Moderate maternal drinking and outcome of pregnancy. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9(6):599–606. doi: 10.1007/BF00211433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kesmodel U, Olsen SF, Secher NJ. Does alcohol increase the risk of preterm delivery? Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):512–518. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parazzini F, Chatenoud L, Surace M, Tozzi L, Salerio B, Bettoni G, Benzi G. Moderate alcohol drinking and risk of preterm birth. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(10):1345–1349. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albertsen K, Andersen AMN, Olsen J, Gronbaek M. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(2):155. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aliyu MH, Lynch ON, Belogolovkin V, Zoorob R, Salihu HM. Maternal alcohol use and medically indicated vs. spontaneous preterm birth outcomes: A population-based study. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(5):582–587. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitehead N, Lipscomb L. Patterns of alcohol use before and during pregnancy and the risk for small-for-gestational-age birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(7):654–662. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passaro KT, Little RE, Savitz DA, Noss J. The effect of maternal drinking before conception and in early pregnancy on infant birthweight. The ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):377–383. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaddoe VWV, Bakker R, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EAP, Witteman JCM. Moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight and preterm birth: The generation R study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VWV, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)-a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2011;118(12):1411–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cook JL, Randall CL. Ethanol and parturition: a role for prostaglandins. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1998;58:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(98)90153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Challis JRG, Sloboda DM, Alfaidy N, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Patel FA, Whittle WL, Newnham JP. Prostaglandins and mechanisms of preterm birth. Reproduction. 2002;124:1–17. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ornoy A, Ergaz Z. Alcohol Abuse in Pregnant Women: Effects on the Fetus and Newborn, Mode of Action and Maternal Treatment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7:364–379. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koren G. Medication Safety in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkowitz GS, Holford TR, Berkowitz RL. Effects of cigarette smoking, alcohol, coffee and tea consumption on preterm delivery. Early Hum Dev. 1982;7(3):239–250. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(82)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henderson J, Kesmodel U, Gray R. Systematic review of the fetal effects of prenatal binge-drinking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(12):1069–1073. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.054213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kilduff C, Dyer S, Egbeare D, Francis N, Robbe I. Does alcohol increase the risk of preterm delivery? Epidemiology. 2001;12(5):589–590. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YJ, Lee BE, Park HS, Kang JG, Kim JO, Ha EH. Risk factors for preterm birth in Korea. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2005;60(4):206–212. doi: 10.1159/000087207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peacock JL, Bland JM, Anderson HR. Preterm delivery: Effects of socioeconomic factors, psychological stress, smoking, alcohol, and caffeine. BMJ. 1995;311(7004):7531. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7004.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savitz DA, Murnane P. Behavioral influences on preterm birth: A review. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):291. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d3ca63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Windham GC, Fenster L, Hopkins B, Swan SH. The association of moderate maternal and paternal alcohol consumption with birthweight and gestational age. Epidemiology. 1995;6(6):591–597. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mariscal M, Palma S, Llorca J, Pérez-Iglesias R, Pardo-Crespo R, Delgado-Rodríguez M. Pattern of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk for low birth weight. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Volume I, College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Population Projections U.S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2000–2050. [Accessed 08.30.2011];2011 Available from. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/

- 50.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National vital statistics reports. 16. Vol. 58. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. Births: Preliminary data for 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Law AM, Kelton WD. Simulation Modeling and Analysis. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ernhart CB, Morrow-Tlucak M, Sokol RJ, Martier S. Underreporting of alcohol use in pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988 Aug;12(4):506–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Embree BG, Whitehead PC. Validity and reliability of self-reported drinking behavior: dealing with the problem of response bias. J Stud Alcohol. 1993 May;54(3):334–344. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davis CG, Thake J, Vilhena N. Social desirability biases in self-reported alcohol consumption and harms. Addict Behav. 2010;35(4):302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.001. Epub 2009 Nov 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salihu HM, Kornosky JL, Lynch O, Alio AP, August EM, Marty PJ. Impact of prenatal alcohol consumption on placenta-associated syndromes. Alcohol. 2011;45:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris DS, Tenkku LE, Salas J, Xaverius PK, Mengel MB. Exploring pregnancy-related changes in alcohol consumption between black and white women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(3):505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tenkku LE, Morris DS, Salas J, Xaverius PK. Racial disparities in pregnancy-related drinking reduction. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13(5):604–613. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0409-2. Epub 2008 Sep 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Alcohol Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Women of Childbearing Age — United States, 1991–2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2009;58(19):529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson TD. Nation’s premature birth rate improving, but not enough to make the grade. [Accessed 01.07.2011];The Nation’s Health. 2011 Jan;40(10):E4. Available from. http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/40/10/E48.full. [Google Scholar]