Abstract

Proteasomes are multisubunit enzymes responsible for the degradation of many cytosolic proteins. The inhibition of the proteasome has been the subject of intense interest in the development of drug therapies. We have previously demonstrated that simultaneous administration of a tripeptide aldehyde proteasome inhibitor (MG115 or MG132) with a peptide (Cys-Trp-Lys18) DNA condensate boosted gene expression by 30-fold in cell culture. In the present study, we have developed a convergent synthesis to allow the incorporation of a proteasome inhibitor tripeptide into the C-terminal end of a gene delivery peptide. The resulting peptides formed DNA condensates that mediated a 100-fold enhancement in gene expression over a control peptide lacking all or part of the tripeptide inhibitor. Gene transfer peptides possessing intrinsic proteasome inhibitors were also found to be non-toxic to cells in culture. These results suggest that intrinsic proteasome inhibition may also be used to boost the efficiency of peptide mediated nonviral gene delivery systems in vivo.

Keywords: peptide-mediated gene delivery, proteasome inhibition, peptide synthesis, gene transfer

Introduction

The proteasome is a multisubunit complex that is responsible for the degradation of many cytosolic proteins such as damaged or misfolded proteins (1, 2), degradation of cyclins for cell cycle control (3, 4), destruction of transcription factors that control cell differentiation (3, 4), and processing of foreign proteins for generation of cellular immune responses (1, 5). The 26S proteasome complex is composed of the barrel-like 20S catalytic core capped at the ends by the 19S regulatory subunits (2, 6). The 19S regulatory particles are responsible for substrate recognition, unfolding, and translocation of proteins into the catalytic core. The proteolytic sites of the proteasome are contained inside the core of the 20S complex (7, 8). Unlike many other proteolytic enzymes, the proteasome has multiple peptidase activities that can be classified into three main groups: cleavage after hydrophobic side chains (chymotrypsin-like), cleavage after basic residues (trypsin-like), and cleavage after acidic residues (peptidylglutamyl peptide hydrolysis or PGPH) (6, 7).

Previous work by Duan et al. established the proteasome to be a key route of metabolism for viral gene delivery vectors (9). In studies of airway epithelial cells, it was found that the adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector was ubiquitinated after endocytosis and targeted for degradation by the proteasome. Co-administration of tripeptide proteasome inhibitors increased gene expression from the apical surface by over 200-fold in cell culture and also increased AAV-mediated gene transfer in the liver and lung (9).

Nonviral vectors are often composed of cationic peptides, polymers, and lipids that interact with the negatively charged backbone of DNA to form nanometer sized particles that spontaneously transfect cells in culture (10). The intracellular dissociation and subsequent metabolism of a cationic peptide polymer leads to the release and premature metabolism of plasmid DNA by DNAse leading to a low level and short duration of expression (11). The enzymes responsible for the metabolism of peptide mediated nonviral delivery systems are believed to be in the lysosomes (12), however recent evidence has implicated the involvement of the proteasome (13).

Kim et al. hypothesized that peptide-DNA condensates could follow a similar route of metabolism as viruses due to their comparable size and susceptibility to serine proteases (13). Transfection of HepG2 cells in the presence of tripeptide proteasome inhibitors resulted in a 30-fold increase in luciferase expression for peptide-DNA condensates, whereas Lipofectamine and polyethylenimine transfections were not enhanced. However, simultaneous uptake of condensate and inhibitor can be difficult and these tripeptide inhibitors are very cytotoxic, with an LD50 of approximately 2 µM (13).

Peptide vinyl esters are a new class of proteasome inhibitors that are suggested to work through a mechanism similar to the well-known peptide vinyl sulfone inhibitors, such as NLVS (14–17). The C-terminal vinyl ester covalently modifies the active site of the proteasome by serving as a substrate for a Michael addition with the catalytic threonine residue at the N-terminus of the β subunit (14). We hypothesize that gene delivery peptides containing an intrinsic C-terminal vinyl ester moiety may resist metabolism by the proteasome and thereby increase the gene transfer efficiency of peptide-DNA condensates. Here we describe the synthesis and testing of gene delivery peptides containing a variety of intrinsic peptide vinyl ester sequences that condense DNA, mediate cellular uptake, inhibit the proteasome, and boost gene transfer efficiency. Incorporation of the peptide inhibitor sequence into the DNA condensate provides a mechanism for co-internalization of the proteasome inhibitor with the peptide-DNA condensate without the cytotoxic effects of giving a separate inhibitor.

Materials and Methods

(Benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tris(dimethylamino)phosphonium hexafluorophosphate, N-terminal Fmoc protected amino acids, N-terminal Boc protected amino acids, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole, diisopropylcarbodiimide, and 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin for peptide synthesis were obtained from Advanced ChemTech (Lexington, KY). Triethylamine, ether, trifluoroacetic acid, hexane, ethyl acetate, and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher. Dichloromethane, N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride, lithium aluminum hydride, tetrahydrofuran, triethylphosphonoacetate, potassium tert-butoxide, acetic acid, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol, diisopropylethylamine, and thiazole orange were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). HepG2 cells were provided by the Center for Gene Therapy of CF in the University of Iowa. DMEM, Hams-F12, sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, and inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). A 5.6 kbp plasmid (pCMVL) encoding the reporter gene luciferase was a gift from Dr. Hickman at the University of California (Davis, CA, USA). Endotoxin-free plasmids were purified from Escherichia coli on a Qiagen ultrapure column according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase from Photinus pyralis, D-luciferin, and ATP were purchased from Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Indianapolis, IN, USA). BCA assay kit was from Pierce Biotechnology Inc. (Rockford, IL, USA). MG 115 (Z-Leu-Leu-Nva-CHO) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA).

Synthesis of Leu-ve and Nva-ve

Leu-ve and Nva-ve were synthesized by modification of methods of Fehrentz and Castro (18). The peptide aldehyde was converted to the vinyl ester according to the procedure of Hover et al (19). Briefly, triethylamine (2.2 g, 22 mmol) was added to a solution of Boc-amino acid 1 (5.0 g, 22 mmol) in 90 ml dichloromethane (DCM), followed by the addition of (benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tris(dimethylamino)phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (BOP; 9.6 g, 22 mmol). After 5 min, N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride (2.3 g, 24 mmol) and triethylamine (2.4 g, 24 mmol) were added and the reaction was stirred at RT under nitrogen. Approximately 0.5 ml of additional triethylamine was added to the reaction to raise the pH to 7. The reaction was monitored by TLC (1:1 ethyl acetate:hexane, Rf = 0.52) and reached completion within 45 min. The mixture was diluted to 150 ml with DCM and washed successively with 3N HCl (3 × 50 ml), saturated NaHCO3 (3 × 50 ml), and saturated NaCl (3 × 50 ml). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and evaporated to give 2.

Lithium aluminum hydride (LAH; 0.95 g, 25 mmol, 5 equiv) was added to 150 ml of tetrahydrofuran (THF) under nitrogen. The LAH slurry was then added drop wise to 2 in 50 ml THF and mixed for 20 min under nitrogen. The mixture was hydrolyzed with potassium hydrogen sulfate (4.77 g, 35 mmol) in 100 ml water and the THF was evaporated. Ether (200 ml) was added and the aqueous layer was separated and extracted with 3 × 50 ml ether. The organic phases were combined, washed with 3N HCl (3 × 50 ml), saturated NaHCO3 (3 × 50 ml), and saturated NaCl (3 × 50 ml), and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was then evaporated to give 3.

Triethylphosphonoacetate (3.11 g, 15.5 mmol) was added to 58 ml THF and cooled to 0°C. Potassium tert-butoxide (1.56 g, 13.9 mmol) in 14 ml THF was added and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then cooled to 5°C and aldehyde 3 was added in 23 ml THF and the reaction was stirred for two hrs at room temperature until reaction was shown to be complete by TLC (9:1 hexane:ethyl acetate, Rf = 0.25). The solvent was evaporated and the residue was dissolved in 200 ml of 50% ether in water. The aqueous phase was then extracted with ether (2 × 100 ml) and the combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was evaporated. The residue was then purified by flash chromatography using 9:1 hexane:ethyl acetate to give 4. The Boc-protected vinyl ester 4 was then treated with 90% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water for 40 min followed by evaporation of the TFA. The residue was precipitated with ether and the resulting solid was separated by centrifugation to give vinyl ester 5 in an overall yield of 40%.

The product was characterized by proton NMR (300 MHz, acetone-d6): δ = 6.98 (dd, J = 7.2 Hz, 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (dd, J = 1.2 Hz, 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (m, 1H), 4.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.98–2.10 (m, 1H), 1.64–1.76 (m, 2H) 1.24 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz, 6.3 Hz, 6H). MS: M+H+ = 186.1.

Nva-ve was synthesized by an identical approach with an overall yield of 48%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, acetone-d6): δ = 6.99 (dd, J = 6.9 Hz, 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (dd, J = 0.9 Hz, 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.86 (m, 1H), 4.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.80–1.95 (m, 2H), 1.35–1.50 (m, 2H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.93 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H). MS: M+H+ = 172.1.

Intrinsic Proteasome Inhibitory Gene Transfer Peptide Synthesis

Peptides of the following sequences WK18, WK18LL, WK18VS, WK18VQ, WK18FQ, WK18YVQ, and WK18FVQ were synthesized on 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin at a 30 µmol scale. Standard Fmoc procedures were used with 1-hydroxybenzotriazole and diisopropylcarbodiimide double couplings on an Apex 396 Advanced ChemTech solid-phase peptide synthesizer. N-terminal and side-chain protected peptides were cleaved from the resin by reaction with acetic acid/2,2,2-trifluoroethanol/DCM (1:1:8 (v/v/v)) for 30 min at RT. Fifteen volumes of hexane were then added and the solvent was evaporated to give the crude protected peptide.

Each protected peptide (4 µmol) was dissolved in THF and diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA; 4 µmol), BOP (12 µmol), and HOBt (24 µmol) were added. The vinyl ester 5 (20 µmol) and DIPEA (20 µmol) were added and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 hrs. The solvent was then evaporated and the peptide was deprotected with 90% TFA for 1 h. Following evaporation, the peptide was dissolved in water for purification. Peptides were purified on RP-HPLC by injection onto a Vydac C18 semipreparative column (2 × 25 cm) eluted at 10 ml/min with a 0.1% TFA and a 20–30% gradient of acetonitrile over 30 min while monitoring absorbance at 280 nm. The major peak was collected and pooled from multiple runs, concentrated by rotary evaporation, and lyophilized. Purified peptides were reconstituted in water and quantified by absorbance (ε280 = 5600 M−1cm−1) to determine the isolated yield, which ranged from 18–45%. The peptides were characterized on an Agilent 1100 LC-ESI-ion trap by injecting 2 nmol onto a Vydac C18 analytical column (0.47 × 25 cm) eluted at 0.7 ml/min with 0.1% TFA and a 5–55% gradient of acetonitrile over 30 min. The RP-HPLC eluent was directly infused into the electrospray ionization source and mass spectral data was obtained in the positive mode for all peptides. Peptides containing a C-terminal nor-Val vinyl ester (Nva-ve) were also synthesized using the same method described above.

Preparation and Characterization of Peptide-DNA Condensates

Peptide DNA condensates were prepared by combining 50 µg of pCMVL in 500 µl of Hepes-buffered mannitol (HBM; 5 mM Hepes, 0.27 M mannitol, pH 7.5) with 20 nmol of peptide in 500 µl HBM while vortexing to create DNA condensates possessing a charge ratio (NH4+:PO4−) of approximately 2:1. The particle size of DNA condensates was measured by quasi-elastic light scattering (QELS) on a Brookhaven ZetaPlus particle sizer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, NY, USA). The relative binding affinity of the peptides for DNA was monitored by two methods. In the first method, peptide-DNA condensates (40 µl) of varying stoichiometries were added to 960 µl of HBM containing 0.1 µM thiazole orange. The fluorescence of the intercalated dye was measured using a LS50B fluorometer (Perkin Elmer) by exciting at 498 nm while monitoring emission at 546 nm with both the excitation and emission slit widths set at 8.5 (20). Peptide mediated condensation was also monitored by a band shift assay. Condensates with increasing peptide to DNA ratios (0–1 nmol peptide per µg of DNA) were electrophoresed on an agarose gel (1 µg DNA per well) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining (21).

In Vitro Gene Expression

HepG2 cells (5 × 105) were plated on 6 × 35 mm wells and grown to 40–70% confluency in DMEM supplemented with 50% Hams-F12, 10% FBS, 250 U/ml penicillin and 250 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Transfections were performed in DMEM (1 ml/35 mm well) supplemented with 2% FBS, sodium pyruvate (1 mM), penicillin and streptomycin (100 U and 100 µg/ml). Peptide-DNA condensates (10 µg of DNA in 0.2 ml of HBM) were added drop wise to triplicate wells. After a 4 h incubation at 37°C, the medium was replaced with 2 ml fresh culture medium (DMEM containing 50% Hams-F12 and 10% FBS). Following a total of 24 hrs incubation, the cells were washed twice with 2 ml ice-cold PBS (calcium- and magnesium-free) and then treated with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris hydrochloride, pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA, 8 mM magnesium chloride, 1% Triton X-100) for 10 min at 4°C. The cell lysate was scraped, transferred to a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube, and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 g at 4°C to pellet the cell debris. Lysis buffer (300 µl), sodium-ATP (4.3 µl of a 165 mM solution, pH 7, 4°C), and cell lysate (100 µl, 4°C) were combined in a test tube, briefly mixed, and immediately placed in the luminometer. Luciferase relative light units were measured by a Lumat LB 9501 (Berthold Systems, Germany) with 10s integration after automatic injection of 100 µl of 0.5 mM D-luciferin. The relative light units were converted to fmol using a standard curve generated by adding a known amount of luciferase to 35 mm wells containing 40–70% confluent HepG2 cells. The resulting standard curve had an average slope of 1 × 105 relative light units/fmol of enzyme. Protein concentrations were measured by BCA assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard (22). The amount of luciferase recovered in each sample was normalized to milligrams of protein and reported as the mean and standard deviation obtained from triplicate transfections.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The in vitro toxicity of the vinyl ester peptides was evaluated by the MTT reduction assay (23). HepG2 cells were plated on 6 × 35 mm wells at 5 × 105 cells/well and grown to 40–70% confluency. The culture media was then replaced with 1 ml of fresh DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and the cells were treated with either 0.4 nmol peptide/µg DNA condensates or varying concentrations of peptide alone. After 4 hrs of incubation with condensates or peptide, the media was removed and replaced with 2 ml of the original growth media and the cells were allowed to incubate for another 20 hrs. The media was then removed, replaced with 2 ml fresh culture media, and 500 µl of 0.5% (w/v) MTT in PBS solution was added and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 1 h to promote formation of formazan crystals. The media containing MTT was removed and the crystals were dissolved by the addition of 1 ml DMSO and 250 µl Sorenson’s glycine buffer (0.1 M glycine, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 10.5) and measured spectrophotometrically at 595 nm on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Bethesda, MD, USA). The percent viability was determined relative to untreated cells.

Results

Proteasomes play a major role in the degradation of intracellular proteins and peptides (2, 8). Previous studies by Kim et al. demonstrated that simultaneous administration of peptide-DNA condensates and a proteasome inhibitor, such as the peptide aldehyde MG115, could increase gene expression by 30-fold over control (13). The proposed mechanism involves blocking the premature metabolism of the peptide DNA condensates in the cell.

Although tripeptide aldehydes such as MG115 or MG132 were shown to increase gene transfer, they simultaneously induced apoptosis and produced dose-dependent cell toxicity. In an effort to inhibit the proteasome to increase gene transfer while avoiding cell toxicity we hypothesized that a single DNA condensing peptide containing an intrinsic proteasome inhibitor would potentially block the proteasome, avoid cellular toxicity and could be used to increase gene transfer efficiency in vivo.

We first attempted the synthesis of WK18 with a C-terminal LLnV-aldehyde similar to MG115 using a Weinreb-amide resin. Although the synthesis was successful, the purified WK18-LLnV-aldehyde formed intramolecular Schiff’s-bases with the K18 side chains resulting in a mixture of isomers. The mixture of peptides was also found to be a poor inhibitor of the proteasome that did not provide enhanced gene transfer.

The strategy was refined by incorporating a less reactive C-terminal vinyl ester proteasome inhibitor sequence into the gene delivery peptide (14, 15). Tripeptide analogues possessing a C-terminal vinyl ester have been shown to act as a Michael acceptor for the nucleophilic hydroxyl group of the catalytic threonine residue at the active site of the proteasome (14, 15).

We first approached the synthesis of WK18LLnV-vinyl ester (ve), by releasing the fully protected WK18LLnV-aldehyde from the Weinreb amide resin with LAH, followed by its direct conversion to the vinyl ester using a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction (19, 24–26). This strategy was successful, but only afforded 1% yields of the desired WK18LLnV-ve and proved difficult to optimize.

A higher yielding more general strategy involved the solid phase synthesis of WK18LL on a 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin followed by a mild acid cleavage to release the fully protected peptide from the resin (Scheme 1). Subsequent coupling of the N-terminus of a chemically synthesized Leu-ve or Nva-ve to the C-terminus of the protected peptide, followed by deprotection and purification, established a general convergent high-yielding pathway to the desired WK18LLnV-ve (42%) and related peptides (18–45%) (Table 1). During the coupling of the head group to the protected peptide with BOP, it was essential to use excess HOBt to suppress racemization at the α-carbon of the C-terminal leucine of the WK18LL. Without the excess HOBt, the reaction produced two products of identical mass that represent the L-D isomerization.

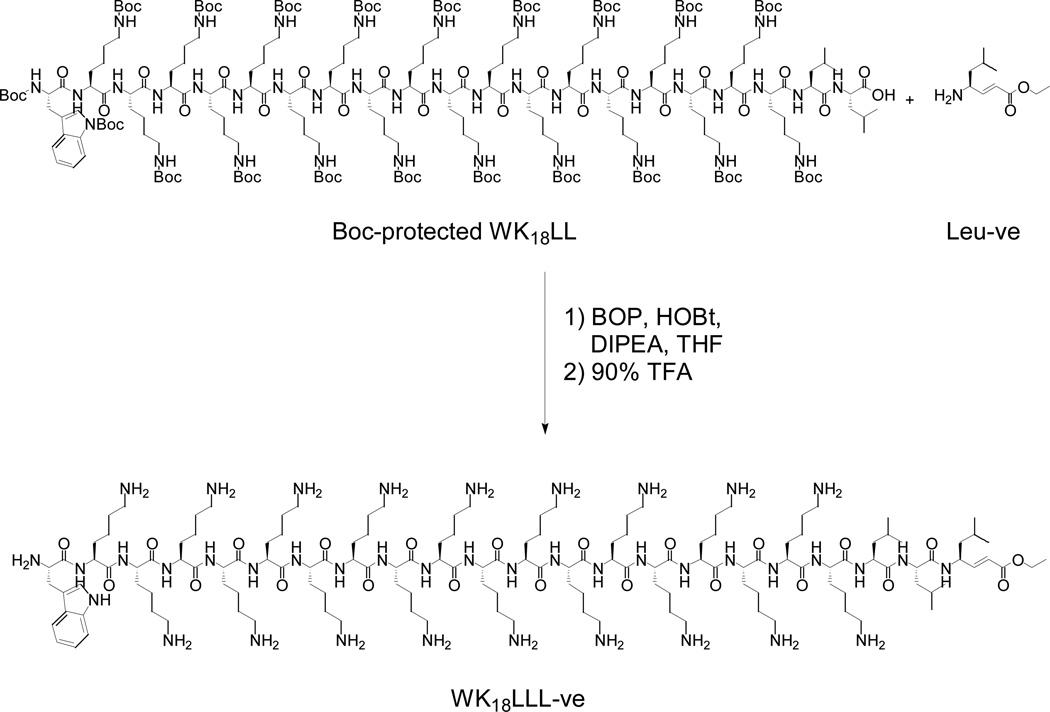

Scheme 1. Convergent Synthesis of WK18LLL-ve Gene Transfer Peptide.

The C-terminus of the fully protected WK18LL peptide prepared on chlorotrityl resin is conjugated with the N-terminus of Leu-ve, then deprotected to form WK18LLL-ve.

Table 1.

Vinyl ester peptides.

| Sequence | Mass (obs / calc) |

Particle Size (nm)a |

|---|---|---|

| WK18LLL-ve | 2904.9 / 2904.8 | 100 ± 20 |

| WK18LLnV-ve | 2890.0 / 2891.6 | 112 ± 26 |

| WK18VSL-ve | 2864.8 / 2866.0 | 103 ± 18 |

| WK18VQL-ve | 2905.8 / 2906.8 | 182 ± 45 |

| WK18FQL-ve | 2953.9 / 2955.0 | 104 ± 23 |

| WK18YVQL-ve | 3069.0 / 3070.0 | 110 ± 24 |

| WK18FVQL-ve | 3053.0 / 3054.2 | 117 ± 22 |

Particle size determined by QELS at 50 µg/ml in HBM. Mean diameter determination from the average of 10 measurements ± standard deviation, which is the half-width of the population at the half-height of the peak.

The chemical synthesis of the Leu-ve and Nva-ve head groups proved to be efficient, high yielding and general for most amino acid starting materials (Scheme 2). Using a commercially available Boc amino acid (1), the C-terminus was converted into the Weinreb amide (2) then reduced with LAH to give the aldehyde (3). This intermediate was converted via the Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction to the Boc-Leu-ve (4) and finally deprotected to provide the desired Leu-ve (5) with an overall 40% yield. The same synthetic strategy was also applied to the synthesis of the Nva-ve head group resulting in a 48% overall yield.

Scheme 2. Chemical Synthesis of Leu-ve Head Group.

Starting with Boc-Leu (1), the C-terminus is converted into the Weinreb amide (2). Reduction leads to the formation of aldehyde (3), and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons coupling results in the formation of vinyl ester (4). Final deprotection of Boc results in an overall yield of 40% for Leu-ve (5). The same approach was utilized to synthesize nor-Val vinyl ester (Nva-ve) with comparable yields.

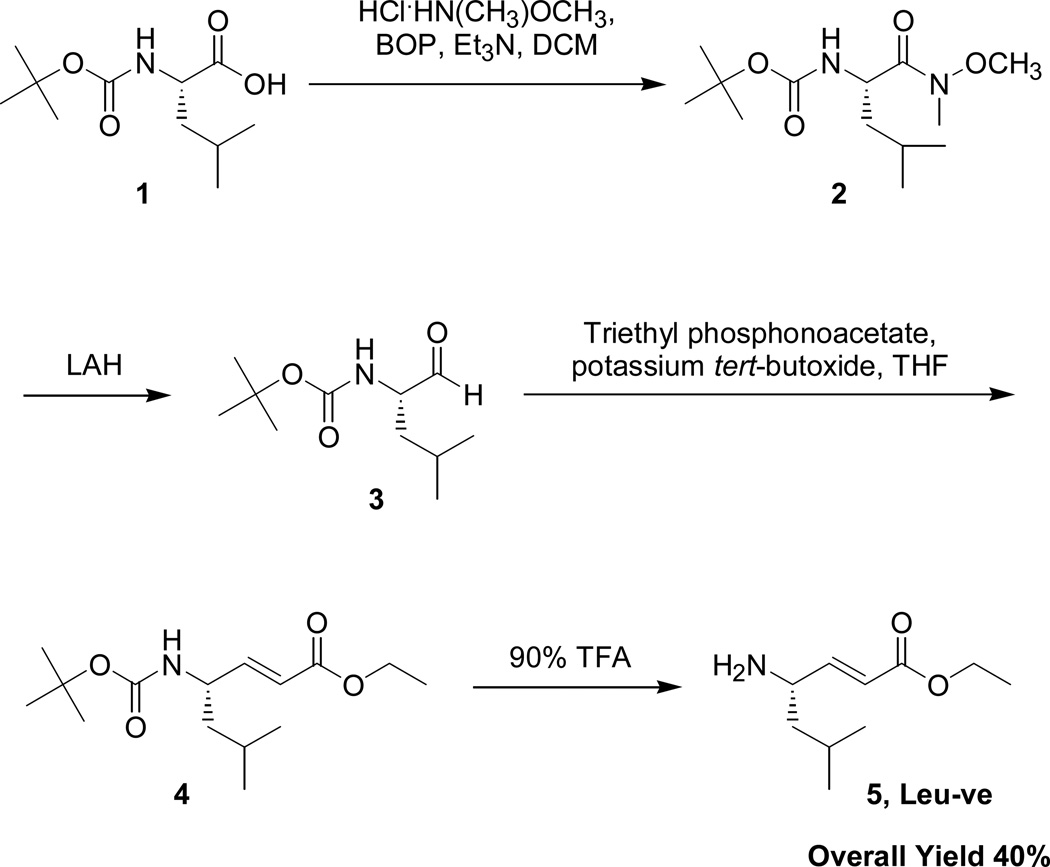

Preparative HPLC purified peptides were re-chromatographed on analytical RP-HPLC to determine yield and establish structure based on mass determined by LC-MS. The RP-HPLC analysis of purified WK18LLL-ve demonstrates purity analysis based on monitoring Trp in eluting peaks by absorbance and fluorescence (Figure 1). For each purified peptide a single major peak demonstrated >95% purity that also produced a doubly charged positive ion in the ESI-MS (Figure 1 inset) corresponding to the calculated mass of the desired peptide (Table 1).

Figure 1. LC-MS Characterization of Purified WK18LLL-ve.

The re-chromatograph of purified WK18LLL-ve on RP-HPLC eluted with 0.1% TFA and acetonitrile is illustrated. The chromatogram was monitored by fluorescence (panel A), absorbance (panel B), and by ESI-MS. The major peak (>95%) at 19.8 min produced a doubly charged positive ion at 1453.4 m/z (inset) corresponding to a mass of 2904.8 amu.

Seven different peptides were prepared containing different head groups and sub terminal amino acids (Table 1). Since it is not known which site is responsible for the degradation of gene delivery peptides, a variety of head groups were designed to act at either the chymotrypsin- or trypsin-like site of the proteasome. The first two peptides with the LLL-ve and LLnV-ve head group sequences were designed based on the sequences of the commercially available peptide aldehyde inhibitors MG132 (Z-LLL-H) and MG115 (Z-LLnV-H). Both the MG132 and MG115 tripeptide inhibitors are known to selectively inhibit the chymotrypsin-like site of the proteasome and were synthesized for this purpose. The other five head groups, VSL-ve, VQL-ve, FQL-ve, YVQL-ve and FVQL-ve, have been shown by Marastoni et al. to selectively inhibit the trypsin-like site of the proteasome when used as tri- and tetrapeptide inhibitor sequences (14, 15).

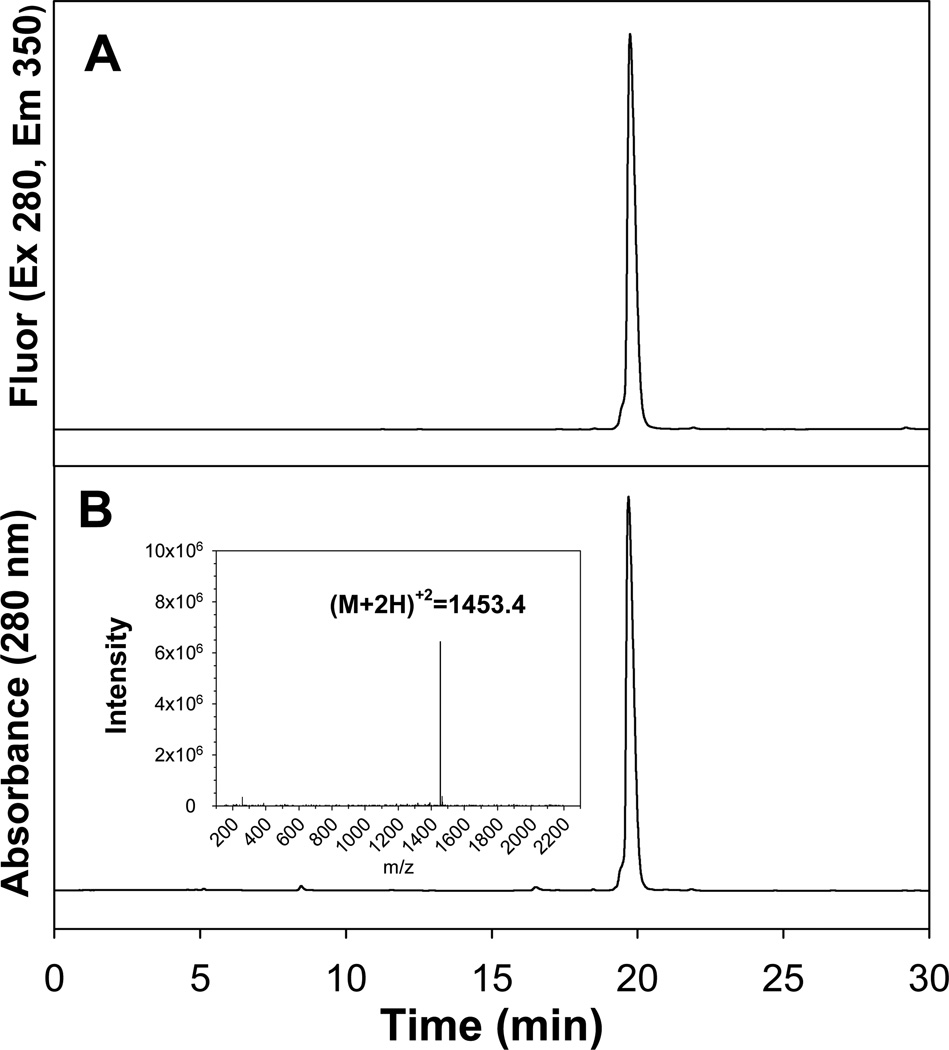

We have previously shown that WK18 is sufficient to condense DNA and form small condensates (27). Each proteasome inhibitor gene transfer peptide was compared for its ability to bind DNA by thiazole orange displacement and gel retardation. The thiazole orange exclusion assay was performed by titrating increasing amounts of peptide with a constant amount of DNA. The displacement of the thiazole orange intercalator dye leads to a decrease in the fluorescence intensity until an asymptote is reached, representing the stoichiometry for complete condensation (Figure 2). WK18 and WK18FQL-ve each reached an asymptote at 0.4 nmol peptide/µg DNA, indicating complete condensation of the DNA. Each proteasome inhibitor gene transfer peptide illustrated in Table 1 had a comparable result with WK18FQL-ve.

Figure 2. DNA Condensation with Proteasome Inhibitor Gene Transfer Peptides.

DNA condensates were formed in triplicate by the addition of 0–1 nmol of WK18 or WK18FQL-ve to 1 µg of plasmid DNA in 1 µM thiazole orange. The fluorescence intensity of thiazole orange was measured (ex 498, em 546) at each ratio of peptide to DNA (upper panel). An asymptote in the fluorescent intensity was observed at a ratio of 0.4 nmol peptide/µg DNA indicating complete condensation. The results observed for WK18 and WK18FQL-ve are representative of those observed for each peptide in Table 1. Similarly, peptide mediated condensation of DNA was monitored by a band shift assay (lower panels). Complete retardation of DNA was observed at 0.2 nmol of peptide per µg of DNA.

The migration of DNA on an agarose gel was compared following the addition of increasing amounts of WK18FQL-ve (Figure 2). Complete retardation of DNA was observed for both WK18 and WK18FQL-ve at 0.2 nmol peptide/µg DNA.

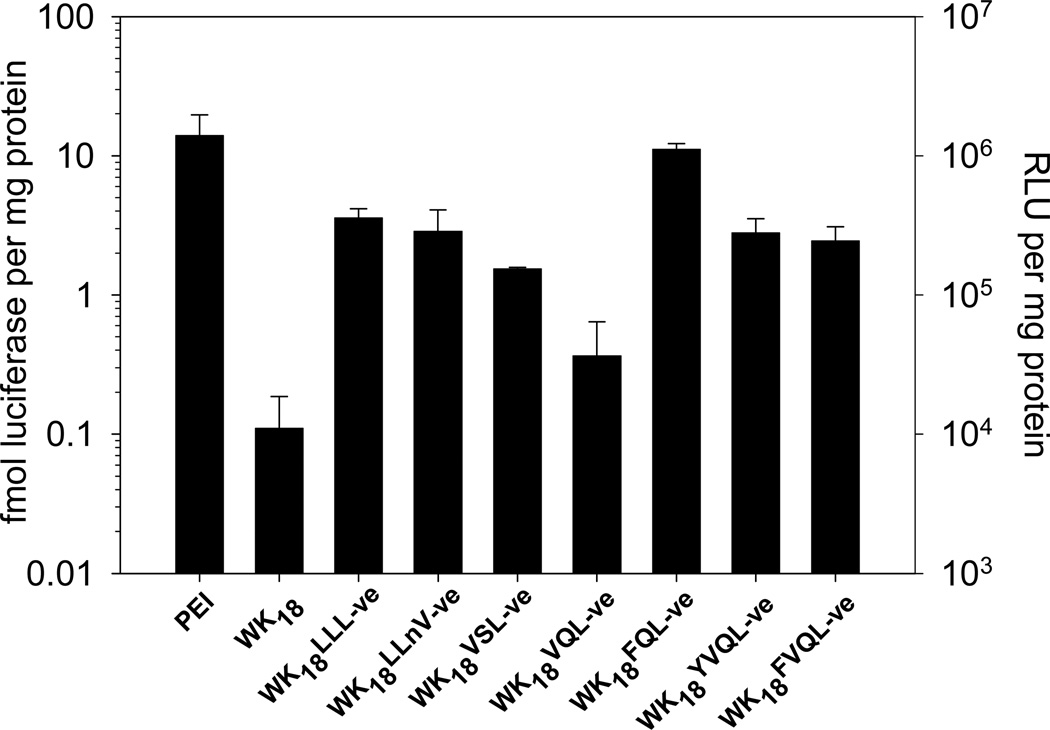

To examine the influence of intrinsic proteasome inhibition on gene expression, HepG2 cells were transfected with DNA condensates prepared with each peptide in Table 1. Luciferase expression was measured for each of the vinyl ester peptides and compared to the controls WK18 and PEI. As illustrated in Figure 3, each peptide-DNA condensate mediated a significant increase in expression relative to WK18, with WK18FQL-ve having a 100-fold increase over WK18 and similar transfection efficiency to PEI.

Figure 3. Efficiency of Proteasome Inhibitor Gene Transfer Peptides.

HepG2 cells were transfected in triplicate with 10 µg of DNA condensed with 4 nmol of each proteasome inhibitory gene transfer peptide and compared to transfections with dose matched controls of PEI:DNA (N:P 9:1) and WK18:DNA. The results establish WK18FQL-ve mediated a 100-fold increase in gene transfer relative to WK18.

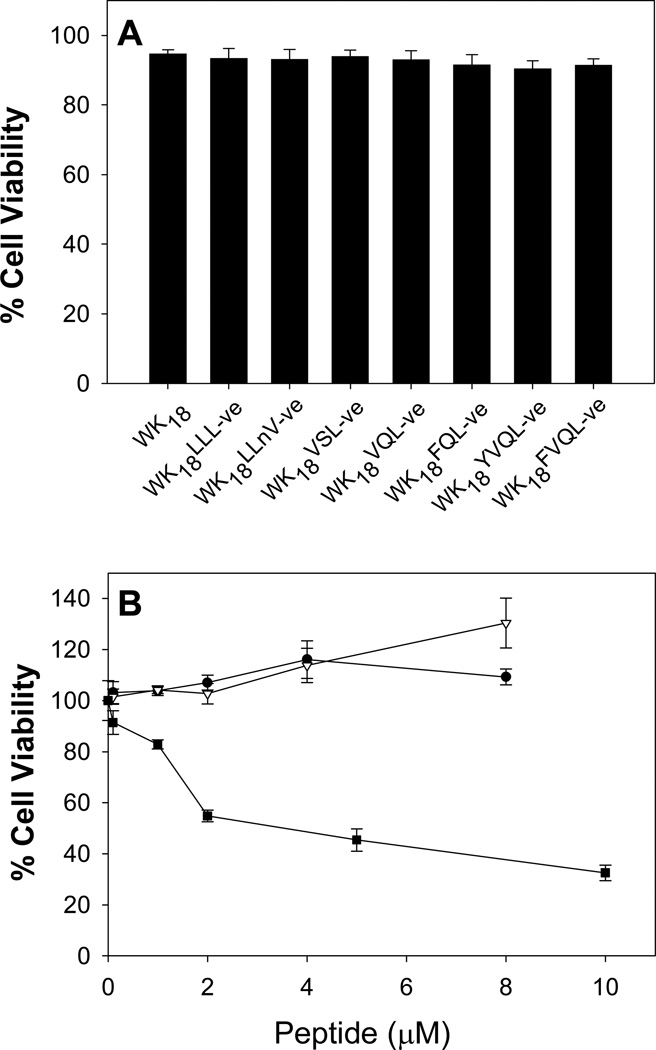

Since other proteasome inhibitors are known to be cytotoxic, each vinyl ester peptide was examined for cytotoxic effects using the MTT assay. HepG2 cells were treated with either peptide-DNA condensates or varying concentrations of free peptide or proteasome inhibitor for 4 h to model the exposure during gene transfer experiments. The results established that a peptide-DNA condensate dose of 4 nmol peptide and 10 µg DNA was not cytotoxic to HepG2 cells (Figure 4A). A similar result was obtained when treating HepG2 cells with varying concentrations of either WK18 or WK18FQL-ve, which established the lack of toxicity even at the highest concentration of 8 µM (Figure 4B). These results are in contrast to the peptide inhibitor MG115 that produces an LD50 of 2 µM.

Figure 4. Relative Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitory Gene Transfer Peptides.

HepG2 cells were treated for 4 hrs with 10 µg of DNA condensed with 4 nmols of each proteasome inhibitory gene transfer peptide. The cell toxicity was assessed by the MTT assay. The results illustrated in panel A demonstrate to lack of cytotoxicity on HepG2 cells. Similarly, the results presented in panel B demonstrate that treatment of HepG2 cells with increasing concentration of WK18FQL (●) or WK18 (▲) results in no toxicity up to 8 µM, where the tripeptide MG115 (■) is toxic to cells at 2–5 µM.

Discussion

The proteasome is an important enzyme that degrades cellular proteins and has recently been implicated in the metabolism of both viral and nonviral gene delivery systems (9, 13). It was first shown that proteasome inhibitors could enhance gene expression mediated by an adeno-associated virus in CF/T1 cells (9). More recently, the addition of a tripeptide aldehyde proteasome inhibitor, such as MG115 or MG132, resulted in significant increase in gene expression when cells were transfected with peptide-DNA condensates (13). This increase in gene transfer was not observed for non-peptide systems, such as PEI or Lipofectamine, or in the presence of lysosomal enzyme inhibitors, therefore indicating the proteasome’s involvement in the degradation of the peptide delivery systems. However, these peptide aldehyde inhibitors are cytotoxic with an LD50 of 2 µM or less. Therefore, we hypothesized that an intrinsic proteasome inhibitor sequence could be built into the gene delivery peptide to inhibit the proteasome, reduce the cytotoxicity of the inhibitor, and increase gene transfer efficiency.

In support of this hypothesis, several peptides were designed with an N-terminal cationic region for DNA binding and a C-terminal head group sequence for proteasome inhibition. Originally this design included an aldehyde at the C-terminus of the peptide in an effort to build in either the MG115 or MG132 proteasome inhibitor sequence. However, the aldehyde proved to be difficult to synthesize in high yields along with being quite reactive with the side chain amines of the lysine residues in forming a variety of intramolecular Schiff’s bases. To solve this problem, we incorporated a vinyl ester inhibitor sequence recently developed by Marastoni et al. (Schemes 1 & 2, Figure 1) (14–17). The vinyl ester head group is similar to the well-known vinyl sulfone class of proteasome inhibitors and is believed to function through a similar mechanism of Michael addition with the γ-hydroxyl group of the threonine side chain on the proteasome. The group of Marastoni synthesized several tri- and tetrapeptide sequences optimizing the P2 – P4 positions and N-terminal protecting group for potent and selective inhibition at the trypsin-like site of the proteasome. They concluded that a glutamine in the P2 position was favorable for trypsin-like selectivity, along with the presence of aromatic and hydrophobic residues in the P3 and P4/N-terminal protecting group position. Another important discovery is that the vinyl ester inhibitors are nontoxic and do not affect cell proliferation, unlike other classes of proteasome inhibitors (14).

The enhanced gene transfer by cationic peptides was dependent on the presence of a vinyl ester head group (Fig. 3). These results in HepG2 cells were consistent with a similar enhancement in gene transfer observed when treating cells with an MG115, a known tri-peptide proteasome inhibitor. There is no direct evidence that cationic peptides containing a vinyl ester are exclusive in their inhibition of the intracellular proteasome. The inhibition of other proteolytic enzymes could also result in enhanced gene transfer.

Since there are known to be three types of proteolytic acitivites within the proteasome, we synthesized several different sequences targeting both the trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like catalytic activities. Based on the results of Marastoni, we designed peptides that incorporated the most potent vinyl ester tri- and tetrapeptide inhibitor sequences aimed at targeting the trypsin-like activity of the proteasome. We also included two sequences based on those of MG115 (Leu-Leu-Nva) and MG132 (Leu-Leu-Leu) to target the chymotrypsin-like activity, as they are both selective for this site in the form of a peptide aldehyde inhibitor and are weakly inhibitory at the trypsin-like and PGPH sites (28). However, the proteasome is a complex enzyme with allosteric interactions between its subunits (29, 30). Inhibition of one site within the enzyme can lead to activation and/or inhibition of either of the other sites. The gene delivery peptides contain multiple lysine residues which would suggest degradation would most likely occur by the trypsin-like site which cleaves after basic residues. As seen in Figure 3, the peptide WK18FQL-ve gives over 100-fold increase in gene expression over control, suggesting inhibition presumably at the trypsin-like site leads to the highest levels of gene expression. However, there are many interactions within the proteasome between the subunits that could be inhibiting other catalytic activities as well that could be contributing to this increase in expression. Also, the two peptides targeting the chymotrypsin-like site, WK18LLL-ve and WK18LLnV-ve, both gave significant levels of increased gene expression over control, indicating that inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like site also positively affects peptide-mediated gene expression.

In agreement with the data presented by Marastoni, the gene delivery peptides containing a vinyl ester head group were not toxic to cells as determined by the MTT assay (Figure 4). The peptides were tested in the MTT assay as condensates with DNA and dosed as free peptide at increasing concentrations. Both the condensates and free peptide gave no toxicity, unlike MG115 which had an IC50 of 2 – 5 µM. The peptide aldehydes are highly potent at inhibiting the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome (8), but are also very toxic to cells (13). By changing to a vinyl ester head group, we are able to significantly decrease the cytotoxicity of the proteasome inhibitor. Even though Michael addition-type inhibitors are thought to be less potent than MG115, they bind covalently to the catalytic threonine residue for long-term inhibition unlike the reversible aldehyde that only provides transient inhibition (8). However, when used to condense DNA at a 0.4 nmol peptide per µg DNA ratio, a 1 µM concentration of the inhibitor is present in the transfection media. Data by Kim et al showed a 10 µM dose of MG115 is needed to achieve maximal luciferase expression in HepG2 cells (13). Therefore, less of the inhibitor may be required to achieve the inhibition needed to see a significant increase in gene expression. In addition, MG115 only mediated a 30-fold increase in expression over control while the most potent vinyl ester derivative could produce a 100-fold increase in luciferase expression.

Proteasome inhibitors are able to prevent premature degradation of peptide-DNA condensates and give over a 30-fold increase in luciferase expression. However, these inhibitors are highly toxic and induce apoptosis in cells. Incorporation of an intrinsic proteasome inhibitor sequence into a gene delivery peptide results in a nonviral vector that is able to condense DNA, transfect cells, inhibit the proteasome, and increase gene transfer over control peptides without the cytotoxic effects seen with other inhibitors. With these capabilities, the vinyl ester gene delivery peptides may be able to boost the efficiency of peptide mediated nonviral gene delivery systems in vivo.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this work from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (grant DK066212) as well as the AFPE Predoctoral Fellowship in the Pharmaceutical Sciences (MEM).

References

- 1.Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–71. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craiu A, Gaczynska M, Akopian T, Gramm CF, Fenteany G, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. Lactacystin and clasto-lactacystin beta-lactone modify multiple proteasome beta-subunits and inhibit intracellular protein degradation and major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13437–13445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlowski M. The multicatalytic proteinase complex, a major extralysosomal proteolytic system. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10289–10297. doi: 10.1021/bi00497a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg AL. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kisselev AF, Goldberg AL. Proteasome inhibitors: from research tools to drug candidates. Chem Biol. 2001;8:739–758. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, Yang J, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105:1573–1587. doi: 10.1172/JCI8317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomfield VA. DNA condensation. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 1996;6:334–341. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu D, Knapp JE. Hydrodynamics-based gene delivery. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2001;3:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiethoff CM, Middaugh CR. Barriers to nonviral gene delivery. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2003;92:203–217. doi: 10.1002/jps.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J, Chen C-P, Rice KG. The proteasome metabolizes peptide-mediated nonviral gene delivery systems. Gene Therapy. 2005;12:1581–1590. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marastoni M, Baldisserotto A, Cellini S, Gavioli R, Tomatis R. Peptidyl Vinyl Ester Derivatives: New Class of Selective Inhibitors of Proteasome Trypsin-Like Activity. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5038–5042. doi: 10.1021/jm040905d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marastoni M, Baldisserotto A, Trapella C, Gavioli R, Tomatis R. P3 and P4 position analysis of vinyl ester pseudopeptide proteasome inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3125–3130. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marastoni M, Baldisserotto A, Trapella C, Gavioli R, Tomatis R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new vinyl ester pseudotripeptide proteasome inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2006;41:978–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldisserotto A, Marastoni M, Trapella C, Gavioli R, Ferretti V, Pretto L, Tomatis R. Glutamine vinyl ester proteasome inhibitors selective for trypsin-like (beta2) subunit. Eur J Med Chem. 2007;42:586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fehrentz J-A, Castro B. An Efficient Synthesis of Optically Active α-(t-Butoxycarbonylamino)-aldehydes from α-Amino Acids. Synthesis. 1983;8:676–678. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hover JA, Bock CW, Bhat KL. Synthesis of Chiral 3,4-Disubstituted Pyrroles from L-Amino Acids. Heterocycles. 2003;60:791–798. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenzie DL, Kwok KY, Rice KG. A potent new class of reductively activated peptide gene delivery agents. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:9970–9977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adami RC, Collard WT, Gupta SA, Kwok KY, Bonadio J, Rice KG. Stability of Peptide-Condensed Plasmid DNA Formulations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1998;87:678–683. doi: 10.1021/js9800477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujumoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Analytical Biochemistry. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinh TQ, Armstrong RW. Synthesis of Ketones and Aldehydes via Reactions of Weinreb-Type Amides on Solid Support. Tetrahedron Letters. 1996;37:1161–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fehrentz JA, Paris M, Heitz A, Velek J, Winternitz F, Martinez J. Solid Phase Synthesis of C-Terminal Peptide Aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:6792–6796. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehrentz J-A, Paris M, Heitz A, Velek J, Liu C-F, Winternitz F, Martinez J. Improved solid phase synthesis of C-terminal peptide aldehydes. Tetrahedron Letters. 1995;36:7871–7874. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadhwa MS, Collard WT, Adami RC, McKenzie DL, Rice KG. Peptide-mediated gene delivery: influence of peptide structure on gene expression. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 1997;8:81–88. doi: 10.1021/bc960079q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kisselev AF, Garcia-Calvo M, Overkleeft HS, Peterson E, Pennington MW, Ploegh HL, Thornberry NA, Goldberg AL. The caspase-like sites of proteasomes, their substrate specificity, new inhibitors and substrates, and allosteric interactions with the trypsin-like sites. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:35869–35877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Castillo V, Goldberg AL. Proteasome active sites allosterically regulate each other, suggesting a cyclical bite-chew mechanism for protein breakdown. Mol Cell. 1999;4:395–402. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]