Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although advances in early detection and treatment of cancer improve overall population survival, these advances may not benefit all population groups equally, and may heighten racial/ethnic (R/E) differences in survival.

METHODS

We identified cancer cases in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program, who were ≥ 20 years and diagnosed with one invasive cancer in 1995–1999 (n=580,225). We used 5-year relative survival rates (5Y-RSR) to measure the degree to which mortality from each cancer is amenable to medical interventions (amenability index). We used Kaplan-Meier methods and Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate survival differences between each R/E minority group relative to whites, by the overall amenability index, and three levels of amenability (non-amenable, partly and mostly amenable cancers, corresponding to cancers with 5Y-RSR <40%, 40–69% and ≥ 70%, respectively), adjusting for gender, age, disease stage and county-level poverty concentration.

RESULTS

As amenability increased, R/E differences in cancer survival increased for African Americans, American Indians/Native Alaskans and Hispanics relative to whites. For example, the hazard rate ratios (95% confidence intervals) for African Americans vs. whites from non-amenable, partly amenable and mostly amenable cancers were 1.05 (1.03, 1.07), 1.38 (1.34,1.41), and 1.41 (1.37, 1.46), respectively. Asians/Pacific Islanders had similar or longer survival relative to whites across amenability levels; however, several subgroups experienced increasingly poorer survival with increasing amenability.

CONCLUSIONS

Cancer survival disparities for most R/E minority populations widen as cancers become more amenable to medical interventions. Efforts in developing cancer control measures must be coupled with specific strategies for reducing the expected disparities.

In the last several decades, remarkable improvements in cancer survival have been made through advances in early detection and treatment of many cancers (1). However, all segments of the population have not equally benefited and the burden of cancer is disproportionately borne by the socioeconomically disadvantaged and racial/ethnic (R/E) minorities (2–4). According to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries for cancer cases diagnosed in 1998–2000, all R/E populations, with the exception of Asian and Pacific Islander (API) women, experienced lower survival than non-Hispanic whites. More long-term data, available only for African American and white cancer cases in the SEER registries, also show that survival disparities have persisted or widened over the last several decades (1).

A growing body of research has identified many factors contributing to cancer survival disparities by race/ethnicity, with the most convincing evidence pointing to the higher distribution of more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, less adequate healthcare and greater prevalence of comorbidities among many R/E minority populations as compared with whites (2, 5–8). This research provides important information about specific factors and pathways involved in disparities, but it has not sought to explain or been able to elucidate why social disparities in cancer vary across cancer sites and time periods. In this paper, we propose an explanation as to why disparities exist in some time periods and not others, and strongly characterize some cancer sites while leaving others unaffected by disparities. We propose that social disparities emerge in situations where the knowledge, technology and effective medical interventions for controlling a disease exist, allowing individuals with greater access to important social and economic resources (e.g., knowledge, income, beneficial social relations) to delay and avoid death from that disease. In contrast, in situations where effective medical interventions are absent or negligible, social resources are of limited utility, and survival differences between the most and least socially advantaged persons are minimal (9, 10). Applying this line of argument to R/E disparities in cancer survival, the greater importance of resources for cancers that are amenable to medical interventions would lead to significantly larger survival disparities than what would be observed for cancers with more limited early detection and treatment capacities. We tested this prediction by comparing R/E differences in cancer survival across 53 cancer sites among adult cancer cases in the SEER program, diagnosed in 1995–1999 and followed through 2004.

METHODS

Data Source and Population Selection

We obtained de-identified data from population-based registries participating in the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) SEER program. The SEER registries collect information on cancer cases in selected states and metropolitan areas, including information on cancer diagnosis and treatment, patient demographic, vital status and cause of death. Through linkage with the U.S. Census survey data, socioeconomic data, aggregated at cases’ county of residence, are also available.

Because our primary interest was R/E differences in cancer-specific survival, we excluded cases who were diagnosed with: 1) in-situ cancers (International Disease Classification, 9th Revision [ICD-9] codes: 230–234, 273, 289), 2) more than one invasive cancer site, 3) ill-defined, unspecified or unknown cancer site (ICD-9 codes 149, 159, 165, 195, 196, 199, 208, 235, 236, 238, 999), or 4) a cancer that was not microscopically confirmed (e.g., based solely on death certificate, autopsy or radiological/imaging information). We further restricted our analysis to cases that were diagnosed between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 1999, with follow-up data through December 31, 2004, to construct a recent cohort of cases with sufficient follow-up time (5–10 years) and a narrow time period to minimize significant changes in medical interventions. Additional exclusion criteria included cases < 20 years old (n=8,434), and those with missing data on cause of death (n=6,302), race/ethnicity (n=6,041), or socioeconomic status ([SES] n=1,062). The final sample included 580,225 cases diagnosed with 53 cancers sites, accounting for 96% of all cases in SEER during the specified time period. The cases were drawn from the registries for the states of Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah and Hawaii, the metropolitan areas of Atlanta, Detroit, San Francisco/Oakland and Seattle/Puget Sound, Los Angeles County, and several counties in the San Jose-/Monterey area and in rural Georgia.

Variable Definition

Outcome

The study outcome was cancer-specific survival, defined as the time interval (in months) between the dates of diagnosis and death from any cancer when applicable, or the date of last follow-up or death due to non-cancer causes. Because cases with multiple cancers were excluded, death from any cancer was most likely due to the cancer site for which cases were selected, and was therefore used as the event of interest. Cases that did not die or died of causes other than cancer were censored at the date of death or last follow-up.

Amenability of Cancer Survival

We used relative survival rates (RSR) to develop a measure of the degree to which survival from a specific cancer is amenable to medical interventions (amenability index). The RSR is the ratio of observed survival in a patient cohort and the expected survival of a cohort having the same characteristics as the patient cohort in the general population. Because the main difference between a cohort of cancer cases and a similar cohort in the general population is the presence of cancer in the former, the RSR essentially reflects survival from the underlying cancer after correction for other causes of death present in the population.(11) The RSR for a cancer is improved by: 1) earlier detection of the cancer, and/or 2) increased success of treatment due to earlier detection, timely or effective treatment options. Differences in RSRs across cancer sites within a specified time period may, therefore, provide a reasonable measure of adequacy of early detection and treatment services for one cancer site relative to other cancer sites. Using NCI’s SEER*Stat software,(12) we calculated 5-year (5Y) RSRs for 53 cancer sites among cases, aged ≥ 20 years and diagnosed in 1995–1999, excluding cases with multiple primary tumors or tumors that were not microscopically confirmed (e.g., identified only through death certificate and autopsy). The final amenability index ranged from 5% for pancreatic cancer to 99% for prostate cancer. We used this index as both a continuous variable and categorized into three levels of non-amenable, partly amenable and mostly amenable cancers with <40%, 40–69% and ≥70% 5Y-RSRs, respectively. These cut-points were chosen to divide the index into three categories of roughly equal number of cancer site, while at the same time considering breaks in the index values.

Race/ethnicity

Hispanics of any race were classified as Hispanic; all other cases were defined by their R/E group as white, African American, Asian and Pacific Islander (API) and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN). We used additional available information for Hispanics and APIs to create subpopulation groups with at least 1000 cases, resulting in 4 Hispanic subgroups of Mexicans (25.2%), Puerto Ricans (2.9%) and South or Central Americans excluding Brazil (6.5%), and other Hispanics (59.6% unknown origin, 2.0% Cubans and <1% Dominican), and 8 API subgroups of Japanese (23.6%), Chinese (23.4%), Filipinos (22.1%), Hawaiians (6.9%), Koreans (6.9%), Vietnamese (5.6%), Asian Indians or Pakistanis (3.2%), and other APIs (4.8% unknown origin and all others <1%).

Covariates

Covariates included age and disease stage at diagnosis, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES). Disease stage was based on summary staging scheme, classifying cancers into localized, regional, distant and unstaged by the extent of the spread of cancer from its original site. SES was measured by the percent of persons living below the federally defined poverty threshold in 1999 in the patient’s county of residence, and categorized into three levels of <10%, 10–19%, and ≥ 20%.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

We used Kaplan Meier methods to estimate cancer-specific survival rates by R/E and amenability levels, and Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the relative risk of mortality (expressed as hazard ratios) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for cancer-specific mortality for each R/E minority group with whites as the referent group, adjusting for age, disease stage, gender and SES. (13) We tested the interaction between race and amenability by including a cross-product of the relevant variables into the Cox models that adjusted for potential confounders, and examining the log likelihood ratio tests between the models with and without the cross-product term. All significant tests were two-sided and conducted at the 0.05 level of significance. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Gary, NC).

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted additional Cox regression analyses to assess the robustness of the findings: 1) we excluded cases with cancers of lung and bronchus, female breast, prostate and colon to examine whether survival patterns were overly influenced by these common cancers; 2) we excluded cases with cancers of prostate and thyroid with long survival periods which at least partly reflect the slow growth of these tumors, and not high amenability to medical interventions. Exclusion of these cancers (previously classified as mostly amenable) was expected to further increase R/E differences in survival from mostly amenable cancers; 3) we examined R/E patterns in survival from non-cancer causes of death (selected as as events while alive status and death to cancer causes were censored at the last follow-up date and death date, respectively) to test whether the amenability measure reflected cancer-directed medical interventions, and hence was only specific and predictive of R/E disparities in death from cancer, and not other causes of death.

RESULTS

The median follow-up time after a cancer diagnosis was 5.3 years (range: 0.0–9.9 years). As seen in Table 1, the proportion of younger adults increased across amenability levels, with 10.7%, 16.5% and 21.7% of cancer cases aged less than 50 years having non-amenable, partly amenable and mostly amenable cancers, respectively. As expected, the proportion of cases diagnosed with localized stage increased while the proportion of cases dying from cancer decreased dramatically with increasing levels of amenability. Males were over-represented in the non-amenable cancers, but minimal R/E and socioeconomic differences across amenability levels existed.

Table 1.

Percent distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, vital status and disease stage by amenability levels in Study Population, 11 SEER registries, patients aged ≥ 20years, diagnosed from 1995–1999 with follow-up through 2004.

| Total (n=580,225) | Non-amenablea (n=142,488) | Partly amenableb (n=142,596) | Mostly amenablec (n=295,141) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 1995 | 19.0 | 19.5 | 19.1 | 18.7 |

| 1996 | 19.4 | 19.8 | 19.5 | 19.2 |

| 1997 | 20.1 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 20.1 |

| 1998 | 20.5 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 20.5 |

| 1999 | 21.0 | 20.3 | 20.7 | 21.5 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| 20–34 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 5.1 |

| 35–49 | 13.9 | 8.9 | 13.3 | 16.6 |

| 50–64 | 28.8 | 28.2 | 27.1 | 29.9 |

| 65–79 | 40.1 | 46.8 | 38.8 | 37.4 |

| ≥ 80 | 13.5 | 14.3 | 17.7 | 11.0 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| Localized | 47.6 | 14.2 | 29.4 | 72.5 |

| Regional | 21.9 | 28.4 | 26.6 | 16.4 |

| Distant | 19.1 | 44.2 | 22.4 | 5.4 |

| Unknown stage | 11.5 | 13.2 | 21.6 | 5.8 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 50.2 | 56.6 | 50.1 | 47.1 |

| Female | 49.8 | 43.5 | 49.9 | 52.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 9.5 | 11.0 | 9.2 | 9.0 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7.1 | 8.5 | 7.7 | 6.2 |

| Hispanic | 7.8 | 7.4 | 8.0 | 7.8 |

| White | 75.2 | 72.8 | 74.7 | 76.7 |

| Residential county poverty concentration | ||||

| Least poor (<10%) | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Medium poor(10–19%) | 51.3 | 52.5 | 51.3 | 50.7 |

| Poorest (≥ 20%) | 47.1 | 45.8 | 47.0 | 47.7 |

| Vital status (as of 12/31/2004) | ||||

| Deceased – cancer cause of death | 36.4 | 78.6 | 40.0 | 14.2 |

| Deceased – cause of death other than cancer | 13.4 | 10.3 | 16.4 | 13.5 |

| Alive | 50.2 | 11.1 | 43.6 | 72.3 |

Low amenability cancer sites (ICD-9 code) have 5-year-survival rates < 40% and include pancreas (157), pleura (163), liver and intrahepatic bile ducts (155) Other specified leukemia (207), esophagus (150), trachea, lung and bronchus (162), monocytic leukemia (206), gall bladder and extrahepatic bile ducts (156), stomach (151), brain (191), myeloid leukemia (205), uterus, part unspecified (179), hypopharynx (148), myeloma (203), retroperitoneum and peritoneum (158).

Medium amenability cancer sites (ICD-9 code) have 5-year relative survival rates of 40%– 69% and include ovary (183), Lymphosarcoma and reticulosarcoma (200), floor of mouth (144), small intestine (152), endocrine glands and related structures excluding thyroid (194), nose, nasal cavities and middle ear (160), thymus, heart, and mediastinum (164) trachea, oropharynx (146.3–146.9) and tonsil (146.0–146.2), tongue (141), mouth excluding gum and floor and including unspecified parts of mouth, nasopharynx (147), gum (143), colon excluding rectum (153), larynx (161), rectum, rectosigmoid junction, and anus (154), kidney and other and unspecified urinary organs (189), Lymphoid leukemia (204), connective and soft tissue excluding heart (171), Other malignant neoplasms of lymphoid and histiocytic tissue (202).

High amenability cancer site (ICD-9 code) have 5-year relative survival rates ≥ 70% and include other non-epithelial skin (173), bone and articular cartilage (170), vagina, vulva and other and unspecified female genital organs (184), nervous system excluding brain and including unspecified parts (192), cervix uteri (180), penis and other male genital organs (187), major salivary glands (142), male breast (175), eye (190), bladder (188), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (201), corpus uteri (182), female breast (174), placenta (181), melanoma of the skin (172), lip (140), testis (186), thyroid (193), prostate (185).

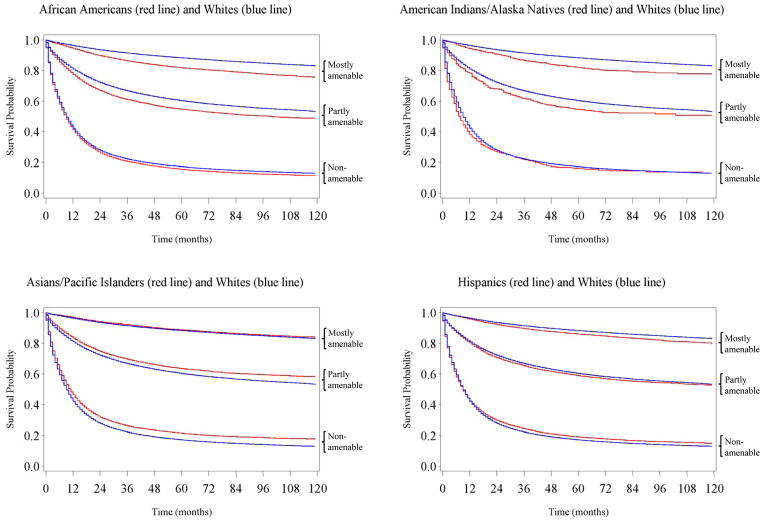

Figure 1 displays survival curves for white cases and each of the four minority populations. As seen in panels 1 and 2, the survival curves for African Americans and AIANs closely resembled the survival curve for whites for non-amenable cancers, but the R/E gaps in survival curves quickly widened as amenability level increased from non-amenable to partly and mostly amenable cancers. Hispanics experienced a more favorable survival for non-amenable cancers as compared with whites, but this survival advantage was lost for partly amenable cancers, and their survival trailed behind whites’ survival for mostly amenable cancers. APIs also had better survival than whites for non-amenable cancers, a pattern that continued for partly amenable cancers until it diminished significantly for mostly amenable cancers.

Figure 1.

Racial Differences in Kaplan Meier Survival Curves by Cancer Amenability Levels

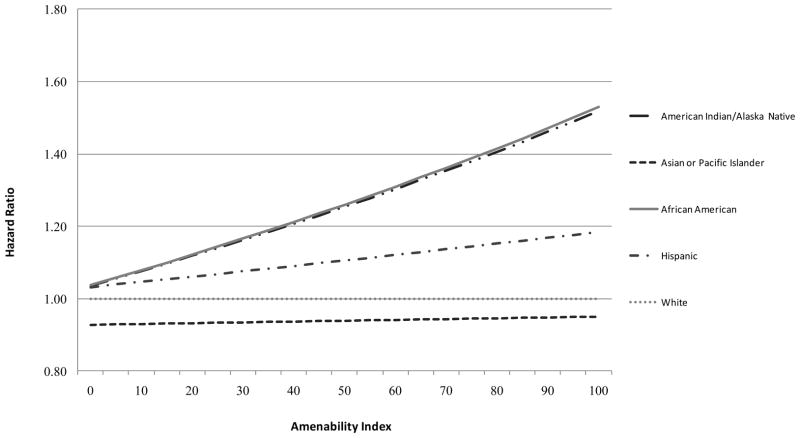

Figure 2 shows the HR of cancer mortality associated with each R/E minority group relative to whites as a function of the cancer amenability index (on a continuous scale), estimated from the Cox proportional hazard models with adjustment for gender, age, stage and SES. The interaction effect of race and amenability was highly significant, as indicated by the log likelihood ratio test (p<0.001). African Americans, and AIANs, and to a lesser extent Hispanics, experienced progressively higher relative risk of mortality than whites as cancer amenability increased. Differences in cancer survival between API and white cases did not depend on the amenability of cancer.

Figure 2.

Change in Adjusted Hazard Ratios of Cancer-specific Mortality associated with minority race by 1% increase in Amenability

Note: model included age at diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, gender, county-level poverty concentration, each race/ethnicity group, 5-year relative survival rates (amenability scale) and interaction between each race/ethnicity group and 5-year-relative survival rates

To further describe the race-by-amenability interaction, we conducted Cox proportional hazard models using the categories of cancer amenability, adjusting for each covariate one at a time before fitting a fully adjusted model (Table 2). Adjustment for gender did not affect R/E patterns in cancer survival by amenability while county-level poverty concentration had a modest effect, with the largest influence observed for AIANs (≈ 4.0% reduction in HRs). Adjustment for age generally increased the HRs for partly and mostly amenable cancers, while adjusting for stage primarily reduced the HRs for mostly amenable cancers. In fully adjusted models, the HRs continued to increase with progressively higher levels of amenability for African American and AIAN cases relative to white cases. For example, the HR from non-amenable, partly and mostly amenable cancers were 1.05 (95% CI: 1.03–1.07), 1.38 (95% CI: 1.34, 1.41), and 1.41 (95% CI: 1.37, 1.46), respectively for African Americans compared with whites. A similar, but less pronounced, pattern was also observed for survival differences between Hispanic and white cases, with no survival differences for non-amenable cancers (HR=1.01, 95% CI: 0.98, 10.3), but poorer survival in Hispanics for partly amenable (HR=1.17, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.21) and mostly amenable cancers (HR=1.13, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.17).

Table 2.

Adjusted Relative Risk and 95% Confidence Intervals of Cancer-specific Mortality for Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups with Non-Hispanic Whites as the Reference by Cancer Amenability Levels

| Race/Ethnicity | Amenability Level | Unadjusted | Adjusted for Age | Adjusted for Gender | Adjusted for Stage | Adjusted for Poverty | Fully Adjusted | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||||||

| African American | Non-amenable | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 |

| Partly amenable | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.22 | 1.31 | 1.27 | 1.35 | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.20 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.19 | 1.38 | 1.34 | 1.41 | |

| mostly amenable | 1.53 | 1.49 | 1.58 | 1.59 | 1.54 | 1.64 | 1.54 | 1.49 | 1.58 | 1.39 | 1.35 | 1.43 | 1.50 | 1.45 | 1.54 | 1.41 | 1.37 | 1.46 | |

| American Indian/ Alaska Native | Non-amenable | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 1.27 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.17 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.21 |

| Partly amenable | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 1.36 | 1.20 | 1.54 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 0.97 | 1.25 | 1.34 | 1.18 | 1.52 | |

| mostly amenable | 1.49 | 1.29 | 1.73 | 1.69 | 1.46 | 1.96 | 1.49 | 1.28 | 1.72 | 1.25 | 1.07 | 1.44 | 1.41 | 1.22 | 1.64 | 1.42 | 1.22 | 1.64 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | Non-amenable | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Partly amenable | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.05 | |

| mostly amenable | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.94 | |

| Hispanic | Non-amenable | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| Partly amenable | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.16 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.21 | |

| mostly amenable | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.31 | 1.27 | 1.36 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.24 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.17 | |

Note: HR=Hazard ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence intervals

adjusted for age, gender, cancer stage and poverty concentration

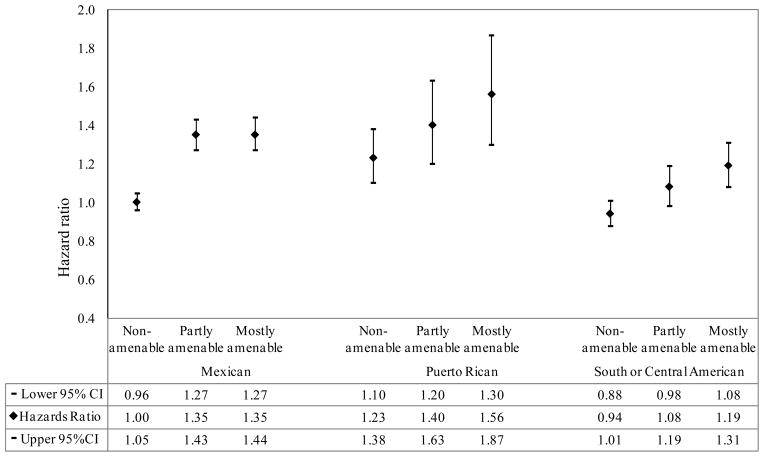

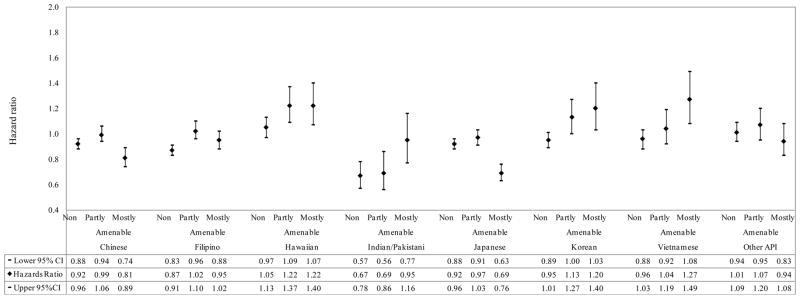

Racial Subpopulation Groups

Figures 3 and 4 present results of Cox regression models using Hispanic and API subgroups. The R/E differences in cancer survival for Hispanic subgroups as compared with the white group became larger as amenability level increased. For example, the HRs from non-amenable, partly and mostly amenable cancers were 1.00 (95% CI: 0.96, 1.05), 1.35 (95% CI: 1.27, 1.42) and 1.35 (95% CI: 1.27, 1.44), respectively, for Mexicans relative to whites. More marked survival differences by amenability levels were also observed when considering the 8 API subgroups separately than when using API as one group. Specifically, Native Hawaiians, Koreans and Vietnamese had progressively worse survival than whites with increasing amenability levels, a pattern observed for non-API R/E groups. Although Indians and Pakistanis had more favorable survival than whites, their survival advantaged decreased with increasing amenability levels (HRs from non-amenable, partly and mostly amenable cancers were 0.67 (95% CI: 0.57, 0.78), 0.69 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.86) and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.77, 1.16), respectively). Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese and other API had similar or better survival relative to whites; however, the largest survival advantage for these groups was observed for mostly amenable cancers.

Figure 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios of cancer-specific mortality comparing Hispanic subgroups with White population by amenability level

Figure 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios of cancer-specific mortality comparing Asian/Pacific Islander subgroups with White population by amenability level

We observed modest R/E variation in the distribution of cancer sites. Lung and bronchus, female breast, prostate, lung and colon cancers were the most common cancers in all R/E populations accounting for cancer diagnosis in 62% of African American, 46% of AIAN, 52% of API, 47% of Hispanic and 55% of white cancer cases. The same common cancers were also represented within each level of amenability for all R/E populations as follows: lung and bronchus and stomach for non-amenable cancers, colon and rectum for partly amenable cancers and female breast and prostate for mostly amenable cancers.

Sensitivity Analyses

Excluding cases diagnosed with the four most common cancers (nearly 45% of all cases) did not significantly affect the overall findings, with the largest change observed for mostly amenable cancers in survival differences between AIAN and whites (15% reduction in HR from mostly amenable cancers). Removing cases with thyroid and prostate cancers widened the R/E disparities for mostly amenable cancer, increasing the HRs by 18.4% for African Americans, 5.6% for AIANs, 15.1% for API and 6.2% for Hispanics, all as compared with whites. We also explored whether R/E differences in survival from non-cancer causes of death also depended on amenability levels. The results showed that African Americans, AIANs and Hispanics experienced lower survival from non-cancer causes of death than whites for all levels of amenability and the growing disparities, observed for cancer mortality risk, were not found for non-cancer mortality risk. As with cancer-specific mortality, APIs had equivalent or more favorable survival than whites for non-cancer causes of death (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We investigated whether R/E disparities in cancer survival increase as available medical interventions improve overall cancer survival, and found clear support of this hypothesis for African Americans, AIANs, Hispanics and several subgroups of the Asian/Pacific Islander population from the SEER coverage areas, diagnosed in the late 1990s. The increasing gradient in survival disparities by cancer amenability levels was steep and remarkably similar for African Americans and AIANs relative to whites. Although less pronounced for the overall Hispanic population, for the two largest Hispanic subgroups of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, the widening survival disparities by increasing amenability was also clearly evident and similar in magnitude to survival differences observed for comparisons involving African Americans and AIANs. The same pattern was not observed for the overall API population and some of its subgroups, who for the most part had the longest survival from most cancers. The survival advantage among API cancer cases as compared with other R/E groups has also been documented in other reports (2, 3, 7, 14, 15), but reasons remain largely unknown. We considered the possibility that API immigrants may have returned to and died in their country of birth, thereby increasing the probability that their deaths were not recorded in the U.S. However, this phenomenon would also apply to the Hispanic cases with significant proportion of immigrants. To reduce the possibility of this bias, we ran our analyses separately for U.S.-born and foreign-born API and Hispanic cases. While foreign-born cases could arguably have been motivated to return to their country of origin, U.S.-born cases would be unlikely to leave the U.S. (their birth place) to die in a foreign country (16). Our results conducted with cases with birth place data (76% of API and 66% of Hispanic cases) did not show significantly different patterns for foreign- and U.S.-born API cases, but larger survival differences from partly and mostly amenable cancers were observed in the U.S.-born Hispanic than in the foreign-born Hispanic cases, both as compared with white cases. A plausible explanation which is compatible with our proposal regarding the use of social resources for delaying death is the relatively high SES profile for several API subgroups as compared with other R/E minority populations. Additional research with more detailed data including socioeconomic data is needed to evaluate this hypothesis.

The observation that survival disadvantage for most R/E minority populations increases as cancers become more treatable may appear counterintuitive at the first consideration, particularly since substantial survival improvements have been documented for all R/E populations (17). We propose, however, that it is precisely this enhanced capacity to successfully treat some cancers, together with the social disadvantage faced by most R/E minorities that give rise to cancer survival disparities. Other studies examining social disparities in disease mortality by varying levels of medical amenability have also provided supportive evidence (10, 18–22). For example, Phelan and colleagues demonstrated steeper socioeconomic gradients in mortality from causes of deaths that were mostly preventable, as determined by expert judgment, than for causes of deaths that were mostly unpreventable in the late 1980s (10). Another recent study found increasing educational disparities in mortality over time for diseases with the most medical progress, as measured by the number of approved therapeutic drugs and improvement in mortality and survival rates (19).

The survival patterns observed in this study also corroborates widely documented R/E differences in survival among cancer cases from population-based databases, single-facility samples, healthcare plans, and clinical trials (4, 7, 23–27). However, most studies have focused on one or a few specific cancers, such as the most common sites or sites with significant disparities, and provided information to explain cancer site-specific survival disparities. In contrast, we compared R/E differences in survival across a spectrum of cancers, classified according to how amenable each cancer site is to available medical interventions. In so doing, we have attempted to illustrate the fundamental role that access to valuable social and economic resources, patterned by race/ethnicity, play in shaping survival disparities. If we are correct in our interpretation that R/E disparities emerge as a result of greater uptake and utilization of available medical interventions by socially advantaged groups, minimizing the relevance of personal resources to obtaining medical care may have the greatest potential for reducing survival disparities. Examples include efforts to reduce complexity of medical procedures, number of visits, and amount of patient time and resource commitment. Increasing the delivery to and utilization of medical care among individuals with limited resources, may also promote a more equitable distribution of medical care in the population. An example of such effort is the patient navigation programs designed to reduce R/E and SES disparities in accessing cancer care (28).

Our study has strengths in using a large racially diverse population-based sample of cancer cases with a wide range of cancers, a relatively long follow-up, and identical data collection systems across R/E populations. Racial/ethnic data in SEER are drawn from administrative and medical records, which may be different from self-reported data. A recent evaluation of racial/ethnic data in the SEER registries against self-reported data from the National Longitudinal Mortality Study surveys suggested excellent agreement between the two sources for data on racial classification (κ=0.90) and moderate to substantial agreement for Hispanic ethnicity (κ=0.61) (29). We used a novel quantitative approach to develop a relative measure of the degree to which cancers are amenable to medical interventions. We found substantial agreement between this measure and a previously published measure of preventability of death from 26 cancer sites, based on average ratings of two independent experts (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.70; weighted kappa=0.57) (10). The validity of the study findings were further strengthened by results of several supplemental analyses confirming a priori hypotheses and by adjustment for several key factors associated with cancer survival. It is worth noting that accounting for the disease stage at diagnosis, a powerful prognostic predictor, only partially accounted for survival differences by race/ethnicity. This is consistent with other reports of persistent survival disparities for many cancer sites after adjusting for disease stage as well as within each stage (1, 2). Furthermore, adjustment for stage primarily affected R/E differences in survival from mostly amenable cancers, and to a lesser degree, for partly amenable cancers. This is consistent with our hypothesis and measurement of amenability index, which suggest a greater variation by R/E in stage at diagnosis for mostly amenable cancers for which early detection and/or effective treatments are available. We were also able to adjust for an SES indicator, percent of persons living below the poverty level in a county, which is strongly associated with other area-based SES indicators in the United States (4). Data on SES characteristics of individual cases or aggregated at smaller geographic units were unavailable in the SEER dataset used for this analysis, limiting our ability to account for differences in individual- and neighborhood level SES, which are likely to be present among persons residing in the large geographic unit of the county.

In conclusion, we found evidence that cancer survival disparities for most R/E minority populations are substantially greater for cancers that can potentially be detected early and treated successfully than cancers with more limited early detection and treatment options. Therefore, medical advances that improve overall survival may not only fail to narrow, but when combined with existing population-level social inequalities, can contribute to R/E disparities in cancer survival. These findings stress the need for considering the impact of emerging cancer discoveries on social disparities and employing specific strategies for averting the unequal burden of cancer.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LAWX, Jamison PM, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, Chu K, Edwards BK. Cancer survival among US white and minorities. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series, Number 4. Bethesda, MD: 2007. Area socioeconomic variations in U.S. cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tammemagi CM, Nerenz D, Neslund-Dudas C, Feldkamp C, DN Comorbidity and survival disparities among black and white patients with breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;294(14):1765–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tammemagi CM, Neslund-Dudas C, Simoff M, Kvale P. In lung cancer patients, age, race-ethnicity, gender and smoking predict adverse comorbidity, which in turn predicts treatment and survival. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(6):597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez SL, O’Malley CD, Stroup A, Shema SJ, WAS Longitudinal, population-based study of racial/ethnic differences in colorectal cancer survival: impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status, treatment and comorbidity. BMC Cancer. 2007;16(7):193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virnig BA, Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Feldman RD, Bradley CJ. A matter of race: early-versus late-stage cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2009;28(1):160–168. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelan JC, Link BG. Controlling disease and creating disparities: a Fundamental Cause perspective. J Gerontol. 2005;60B:27–33. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, Levin B. “Fundamental Causes” of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav. 2004 Sep;45:265–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henson DE, LAR The relative survival rate. Cancer. 1995;76(10):1687–1688. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10<1687::aid-cncr2820761002>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. National Cancer Institute D, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; ( http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/index.html) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time-to-Event Data. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chien C, Morimoto LM, Tom J, Li CI. Differences in colorectal carcinoma stage and survival by race and ethnicity. Cancer. 2005;104(3):629–639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doubeni CA, Field TS, Buist DS, Korner EJ, Bigelow C, Lamerato L, et al. Racial differences in tumor stage and survival for colorectal cancer in an insured population. Cancer. 2007;109(3):612–620. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner KB. The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “Salmon Bias” and Healthy Migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howe HL, Wingo PA, Thun MJ, Ries LAG, Rosenberg HM, Feigal EG, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer (1973 through 1998), featuring cancers with recent increasing trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:824–8442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jemal A, Thun MJ, Ward EE, Henley SJ, Cokkinides VE, TEM Mortality from leading causes by education and race in the United States, 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glied S, Lleras-Muney A. Technological innovation and inequality in health. Demography. 2008;45(3):741–761. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link BG, Northridge ME, Phelan JC, Ganz ML. Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: on the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Q. 1998;76(3):375–402. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kogevinas M, Marmot MG, Fox AJ, Goldblatt PO. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:216–219. doi: 10.1136/jech.45.3.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLancey JO, Thun MJ, Jemal A, Ward EM. Recent trends in Black-White disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2908–2912. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer Disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2913–2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eley JW, Hill HA, Chen VW. Racial differences in survival from breast cancer -results of the National Cancer Institute black/white survival study. JAMA. 1994;272:947–954. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.12.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tripathi RT, Heilbrun LK, Jain V, Vaishampayan U. Racial disparity in outcomes of a clinical trial population with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2006;68(2):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lincourt AE, Sing RF, Kercher KW, Stewart A, Demeter BL, Hope WW, et al. Association of demographic and treatment variables in long-term colon cancer survival. Surg Innov. 2008;15(1):17–2. doi: 10.1177/1553350608315955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargas RB, Ryan GW, Jackson CA, Rodriguez R, Freeman HP. Characteristics of the original patient navigation programs to reduce disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Lin YD, Johnson NJ, et al. Quality of race, Hispanic ethnicity, and immigrant status in population-based cancer registry data: implications for health disparity studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(2):177–87. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]