Abstract

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and second most common cause of cancer deaths in American men. Its long latency, slow progression, and high incidence rate make prostate cancer ideal for targeted chemopreventative therapies. Therefore, chemoprevention studies and clinical trials are essential for reducing the burden of prostate cancer on society. Epidemiological studies suggest that tea consumption has protective effects against a variety of human cancers, including that of the prostate. Laboratory and clinical studies have demonstrated that green tea components, specifically the green tea catechin (GTC) epigallocatechin gallate, can induce apoptosis, suppress progression, and inhibit invasion and metastasis of prostate cancer. Multiple mechanisms are involved in the chemoprevention of prostate cancer with GTCs; understanding and refining models of fundamental molecular pathways by which GTCs modulate prostate carcinogenesis is essential to apply the utilization of green tea for the chemoprevention of prostate cancer in clinical settings. The objective of this article is to review and summarize the most current literature focusing on the major mechanisms of GTC chemopreventative action on prostate cancer from laboratory, in vitro, and in vivo studies, and clinical chemoprevention trials.

INTRODUCTION

The American Cancer Society estimated that 217,730 men developed prostate cancer and 32,050 men died from the disease in the United States in 2010. Prostate cancer remains the most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death among men in the United States (1). The initiation and progression of prostate cancer involves a complex series of both exogenous and endogenous factors. During this progression, genetic changes and loss of cellular control are observed as cell phenotypes change from normal to dysplasia (prostatic in-traepithelial neoplasia or PIN), to severe dysplasia (high-grade PIN or HGPIN), to superficial cancers, and finally to metastatic disease (2–5).

The frequency of latent prostate cancer is evenly distributed, suggesting that external factors such as diet, physical activity, and other lifestyle factors are important in the transformation from latent into more aggressive, clinical cancer (2–5). Prostate cancer incidence, however, varies geographically; incidence rates are the lowest in Asian countries such as Japan, China, Korea, and India, and the highest in the United States and Europe (6–8). Studies indicate that the low clinical incidence of prostate cancer in Asian countries may be due to their high green tea consumption (9,10), because these countries consume 20% of the green tea manufactured worldwide (9).

Tea is a beverage made from the leaves of the Camelia sinensis species of the Theaceae family. Next to water, it is the most widely consumed liquid in the world. The three most common types of tea manufactured are black, oolong, and green teas (11,12). Teas contain a variety of compounds. Flavanols are the main class of flavonoid compounds found in tea, the predominate form being polyphenolic catechins (glavan-3-ols), which are colorless, water-soluble compounds that contribute to the bitterness and astringency of tea (12). The 4 major catechins present in tea are epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin gallate (ECG), and epicatechin (EC) (12).

Studies have suggested that tea consumption has protective effects against a variety of human cancers (13–16). The anticancer activities of tea are attributed to the presence of tea catechins (17). Alternatively, other studies have concluded that tea consumption is associated with increased cancer risk or has no effect on cancer risk (18–22). The inconsistency of epidemiological results may be attributed to different tea brewing conditions, geographical location, and inadequate quantification of tea consumption (11,17). Other contributing confounding factors include the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other nutrients by study participants, and lack of standardization of quantities and compositions of the tea products consumed (23). Individual variations in metabolism possibly due to variations in metabolizing enzymes, human cytochrome P450 (24) and cytosolic catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) (25,26) may also play a role.

Both black and green teas have received attention from researchers because of their potential beneficial health effects, including cancer-preventive and therapeutic effects. During the manufacture of black and oolong teas, most catechins are converted to theaflavins and thearubigins (27), the chemistry of which is still unclear (28). The remaining catechin content of black tea is approximately 3–10% (12). Black tea has been studied for its health benefits. However, in epidemiological studies, the consumption of black tea is generally not associated with lowering cancer risk (29), and further laboratory studies are needed to make conclusive statements (30).

Green tea is the nonoxidized/nonfermented tea product (11,12) that has biological activities including being antimutagenic, antibacterial, hypocholestolemic, antioxidant, antitumor, and cancer-preventive (31,32). In contrast to black tea, green tea has a catechin content of 30–42% of its dry weight (11). This high content of catechins, particularly of EGCG (33), has been shown to be the main effector of the anticarcinogenic properties of green tea. The catechin content of green tea, in addition to its efficacy in preventing progression of multiple types of cancer, has led it to be the most studied type of tea for cancer prevention and therapy (27,34).

Chemoprevention is the administration of agents to prevent the induction or delay the progression of cancers (35); the goal is to arrest multistage carcinogenesis before the development of malignancy (35,36). The features of prostate cancer, namely, its high prevalence, long latency, significant mortality and morbidity, and the availability of intermediate stages of prostate cancer progression, provide the most opportunistic and promising approach for evaluating agents for chemoprevention (35,37,38). Even a slight delay in onset and progression has the potential to provide important health benefits (39). Therefore, research focused on prostate cancer chemoprevention holds promise for reducing the burden of cancer on society (40).

Recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated that green tea catechins (GTCs) have chemo preventative properties against prostate cancer (9,10,14), suggesting that the consumption of GTCs is associated with decreased risk and/or slower progression of prostate cancer (41,42). Green tea has potential as a prostate cancer chemopreventive agent because of its low toxicity (43–47), specificity to transformed and malignant cells (48–52), relatively low cost, availability, and acceptability (53). GTCs may also be used as adjuvant treatments with other phytochemicals (54–56), trace nutrients (57–59), and drug compounds (60,61) for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Prostate cancer chemoprevention with green tea has the potential to be appropriately targeted at high-risk patients to prevent carcinogenesis or to patients after initial cancer treatment to prevent reoccurrence (62).

Investigations focusing on the role of GTCs against prostate cancer have used green tea, green tea extracts, and individual GTCs. EGCG is the major and most active catechin in green tea and is the most commonly studied GTC because of its relative abundance and strong cancer-preventative properties (11,12,62). However, EGCG has low rates of absorption and bioavailability when administered orally (19,43,63), and purified EGCG is expensive to produce (64). Additionally, whole mixtures of GTCs may more accurately reflect the human consumption of green tea, possibly due to the fact that tea constituents other than catechins may also have anticarcinogenic activity. Therefore, the combined interaction of tea components and catechins may contribute to the effectiveness of the anticarcinogenic activities of GTC mixtures (23,56,65,66). This observation made it critical to evaluate the benefits of whole tea products, rather than isolated catechins (56). Administration of green tea and green tea extract, however, commonly leads to the side effects of jitteriness and headaches, presumably from the caffeine content (67). Additionally, because of the lack of assurance of infusion contents and variations in cultivation and brewing techniques that can affect the tea catechin content, it has become necessary to use more standardized GTC mixtures for intervention purposes (7). As a result, pharmaceutical green tea dietary supplements have been developed that have the potential to increase the amount of GTCs consumed and reduce the side effects from caffeine, as compared to ingesting green tea beverages (7). Laboratory and clinical investigations have used Polyphenon E (64), a decaffeinated pharmaceutical preparation of tea catechins that contains approximately 50% EGCG and 30% other catechins.

Phase I clinical studies focused on dose-related safety and toxicity have concluded that a single dose of up to 1,600 mg of EGCG (47) and a repeated 10-day dose of 800 mg of EGCG a day was well tolerated (46). Other investigations have concluded that Polyphenon E capsules are well tolerated up to an 800-mg daily dose (25,43–45) and that greater oral bioavailability of free catechins can be reached by taking the capsules on an empty stomach after an overnight fast (45). In short-term clinical trials, GTCs have not been effective against advanced, androgen-independent prostate cancer (68,69). Alternatively, the first proof of principle clinical trial to assess GTCs for chemoprevention of prostate cancer in men with premalignant lesions concluded that GTC preparations were safe and effective for prostate cancer chemoprevention in men with HGPIN and may also be effective in treating symptoms of benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) (70); the long-term follow-up study concluded that the GTC effect on prostate cancer was long-lasting (71). A clinical study in which prostate cancer patients were given daily doses of Polyphenon E before scheduled prostatectomy supported the role of GTCs, particularly pharmaceutical preparations, in the prevention of prostate cancer (72).

Translating laboratory findings into clinical studies continues to be challenging because of variations in dosing and bioavailability between cell culture, animals, and humans (17,19). Although significant variations in bioavailability have been observed (64,73–75) in clinical trials, GTCs are present in human prostate tissue after green tea consumption, demonstrating bioavailability in the target tissues (76). Evidence of safety and efficacy from phase I studies and laboratory studies showing GTC modulation of prostate carcinogenesis warrants continued testing in clinical trials.

MAJOR MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF GTC CHEMOPREVENTIVE ACTIONS ON PROSTATE CANCER

Laboratory, preclinical, and clinical studies have suggested that green tea consumption has chemopreventive and therapeutic effects on cancer (29). In order to use green tea in the most clinically appropriate settings, it is critical to characterize the mechanisms by which the GTCs are exerting anticancer activity. Therefore, the purpose of this review is to discuss the mechanisms of GTC-induced prostate cancer chemoprevention in cell culture, preclinical, and clinical studies to develop a multimechanistic model of prostate carcinogenesis modulation by GTCs. Studies indicate that these mechanisms encompass at least 5 of the 6 hallmarks of cancer (77), specifically, limitless reproductive potential, evading apoptosis, sustained angiogenesis, tissue invasion, and metastasis. Recently, 4 new hallmarks were identified (78). Of these hallmarks, evading the immune system, inflammation, and deregulated metabolism are also affected by GTC treatment of prostate cancer cells and tissues. For the purposes of this review, emphasis is placed on 6 major mechanisms of GTC action discussed in the relevant scientific literature: proteasome inhibition, cell cycle arrest, inhibition of cell proliferation, apoptosis, suppression of carcinogenesis and progression, and inhibition of metastasis. This article will thus facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the chemoprotective properties of green tea catechins, critical for the transition of this research to clinically relevant settings.

Proteasome Inhibition

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is essential for the degradation of cell cycle progression, proliferation, and apoptotic as well as abnormal proteins that result from oxidative damage and mutations (79). Proteasome target proteins include tumor suppressor proteins, p21 (80), p27 (81–83), IκBα (82), and Bax (84), and it is considered an important target for cancer prevention and therapy (79). GTCs inhibit proteasome activity in assays that used purified 20S proteasome, whole cell extract, and intact, living cells (52,85). After drinking the equivalent of 5 cups of green tea, human plasma levels reach a maximum of 1.6 µM, 0.6 µM, and 0.6 µM of EGC, EGCG, and EC, respectively (86). Treating prostate cancer cell lines with similar levels of EGCG (0–0.5 µM), resulted in the inhibition of chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity in LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145 prostate cancer cells. This inhibition resulted in the accumulation of the proteasome targets, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CKI), p27, and the NFκB inhibitor, IκBα, and caused cell cycle arrest (85). Treatment of prostate cancer cells with synthetic GTCs yielded similar results and induced the expression of the proteasome target, Bax, and cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP (52). GTC-induced inhibition of proteasome activity, however, has not been directly confirmed in rodent models or human studies.

Cell Cycle Arrest

Cell cycle dysregulation is an important hallmark of cancer (87,88). The normal progression of cells through cell cycle is a balance between protein regulators, CKIs, cyclins, and cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) (89). During carcinogenesis, transformed cells carry out indefinite and uncontrollable cell divisions through the dysregulation of normal cell cycle sequences. It is therefore important to initiate cell cycle arrest in cancer cells to prevent further cell cycle progression and subsequent cell proliferation. GTC treatment caused cell cycle arrest in human prostate cancer cells (52,85,89,90). EGCG treatment of human prostate cancer cells resulted in cell cycle dysregulation manifested by G1 arrest, upregulation of CKIs, p21, p27, p16, and p18, and downregulation of cyclins D1, E, and CDKs 2, 4, and 6 (52,85,89). Decreased binding of cyclin D1 toward p21 and p27 was also observed (89). These studies indicate the involvement of the CKI-cyclin-CDK machinery in cell cycle arrest of GTC-treated prostate cancer cells. Treatment of NRP-152, hypertrophic rat prostate epithelial cells, with EGCG and androgen ablation treatment, bicalutamide, resulted in cell cycle arrest (60). The role of p21 in cell cycle progression makes it of particular interest to GTC-induced cell cycle arrest. P21 is regarded as the universal inhibitor of CDKs (91,92). Its activation triggers events that result in cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis (91–94). EGCG-treated prostate cancer cells undergo cell cycle arrest and apoptosis mediated by the upregulation of p21 (89,90,95) regardless of androgen responsiveness and p53 status (89,90).

Inhibition of Cell Proliferation

Cell cycle dysregulation leads to cell cycle progression and allows cancer cells to continue to proliferate indefinitely; therefore, the inhibition of cell proliferation is a major mechanism that works in concert with cell cycle arrest to retard malignant growth. GTCs, particularly EGCG, reduced cell viability and proliferation in human prostate cancer cells (50,59,65,89,90,95–105). EGCG treatment resulted in decreased cell numbers of rat prostate cancer cells (60) and TRAMP mouse C1 cells (106). GTC mixtures, green tea infusions, green tea extracts (56,65,98,101, 107), and Polyphenon E (96) also inhibited prostate cancer cell growth. In vivo, GTCs inhibit tumor cell proliferation in TRAMP mice (39,51,108–110), mice with prostate cancer cell xenografts (56,58,96), and Noble rat prostate cancer models (54). Reductions in cancer cell proliferation are manifested by the inhibition of prostate cancer tumor growth in vivo. Intratumor injection of EGCG and ECG, but not EC, caused a reduction in tumor size and completely abrogated flank tumors in androgen-repressed LNCaP 104-R and PC-3 xenografts in athymic nude mice (111). Similar results were observed in SCID mice with flank LNCaP xenografts that were given green tea infusions as drinking water (56). GTC mixtures and EGCG given in drinking water inhibited the growth of androgensensitive CWR22nu1 prostate cancer cell xenografts in athymic nude mice (112).

Prostate cell proliferation is regulated by growth signaling pathways that are augmented during prostate cancer progression and modified by GTC treatment. Two such pathways are the androgen pathway and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) pathway, which both play important roles in prostate cancer cell proliferation and carcinogenesis. The androgen receptor (AR) is a major component of the androgen signaling pathway in prostate cancer. GTC treatment of LNCaP (104) and LNCaP sublines (99) decreased AR expression and transcriptional activity. EGCG and GCG acted on the AR promoter, reducing mRNA levels and the expression of AR target genes, PSA and hK2, by targeting the Sp1 binding site (104). In vivo, EGCG-induced AR repression occurred in the ventral (7) and dorsolateral (108) prostate of TRAMP mice. Additionally, intraperitoneal injection of EGCG into Sprague Dawley rats resulted in lower blood levels of testosterone, a primary growth factor for normal as well as cancer cells in the prostate (113).

Androgen signaling in the prostate is dependent on the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the enzyme 5α-reductase, an important target of androgen signaling related to prostate carcinogenesis (7,33). EGCG inhibited 5α-reductase in cell-free assays (114) and EGCG-induced growth inhibition may be due to its inhibitory effects on 5α-reductase (115). EGCG and ECG were potent inhibitors of 5α-reductase in rat cells and this inhibition acted to reduce proliferation in the rat prostates (115). EGCG treatment of androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells switched DHT from a growth promoter to a growth inhibitor and sensitized cancer cells to apoptosis (105) and green tea infusions reduced DHT levels in SCID mice injected with LNCaP xenografts (56). Changes in endocrine activity induced by GTC treatment may be related to growth inhibition and regression of prostate cancer tumors and may also play a role in the inhibition of cancer initiation and promotion in animal models (113).

PSA is a kallikrein-like serine-protease secreted by prostate epithelium (116). It is regulated by androgens (117,118) and used for the detection and monitoring of prostate cancer (119). PSA may also be directly involved in the invasive ability of prostate cancer cells (102,119,120). It degraded gelatin, type IV collagen, and activated MMP-2; EGCG treatment inhibited these activities in prostate cancer cells (102). EGCG treatment of LNCaP sublines resulted in decreased PSA expression in vitro and decreased tumor PSA expression in R1Ad tumor xenografts in mice (99). GTCs and EGCG inhibited serum PSA levels in athymic mice injected with CWR22Rnu1 cells (112). PSA levels were also modified by GTCs in clinical studies. Although not statistically different, men with HGPIN given GTC capsules had lower PSA levels than men in the control arm (70). Prostate cancer patients given short-term daily doses of Polyphenon E had significant decreases in serum levels of PSA (72). The effects of GTCs on PSA expression have the potential to affect monitoring patient tumor burden (99).

The IGF family plays a pivotal role of regulating cell growth, differentiation, survival, transformation, and metastasis during human malignancies (121,122) and is dysregulated during prostate carcinogenesis (123). IGF-1 and IGFBP-2 are increased and IGFBP-3 is decreased during prostate cancer progression in TRAMP mice (124,125). PSA cleaved the IGF binding protein, IGFBP-3, during prostate cancer progression, increasing the bioavailability of IGF that can bind and activate IGF receptors (125). EGCG is a small molecule inhibitor of IGF-1R activity in vitro (105,126). IGF-induced growth of prostate cancer cells was inhibited by EGCG treatment (105). Reduced IGF-1 levels resulted from the injection of EGCG into rats (113) and decreased IGFR-1 resulted from the treatment of TRAMP mice with EGCG in drinking water (108). GTC infusion of TRAMP mice resulted in the reduction of IGF-1 (39,124,127), and induction of IGFBP-3 (39,124,127). IGF/IGFBP-3 ratios were altered and these changes were associated with inhibition of signal transduction components, P13K, phosphorylated AKT, and ERK 1/2 (124). Prostate cancer patients given short-term daily doses of Polyphenon E had significant decreases in serum levels of IGF-1, IGFBP-3, and IGF-1/IGFBP-3 ratios (72). The expression of IGF signaling proteins seem to be species specific; GTC treatment increased IGFBP-3 TRAMP mice (39,124,127), whereas treatment reduced the protein in prostate cancer patients (72). Nevertheless, these studies suggest that the IGF-1/IGFBP-3 pathway is important for GTC-mediated inhibition of prostate cancer cell proliferation (124) and highlights the importance of reduced cell proliferation in the chemoprevention of prostate cancer.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is the primary form of tumor cell demise triggered by radiation, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy (128–130). Agents that modulate apoptosis affect cancer cell populations and are used in cancer prevention and treatment strategies (131,132). Studies suggest that inducing apoptosis is one of the anticarcinogenic mechanisms of GTCs. EGCG treatment of prostate cancer cells results in apoptosis as evidenced by DNA fragmentation, flow cytometry, and cellular morphology (51,52,65,89,90,95–98,100,105,106,133,134). Additionally, EGCG treatment sensitized TRAIL-resistant LNCaP cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (135). Individual GTCs and GTC mixtures induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells (65,98); GTCs, in combination with copper ions, bicalutamide, or COX-2 inhibitors, synergistically induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells (59–61). GTCs also exert preventative effects against prostate cancer in rodent models, and many of these effects are mediated by their ability to induce apoptosis in prostate cancer tumor cells (39,108,112).

GTCs trigger apoptosis in prostate cancer cells through several mechanisms. GTCs induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by shifting the balance between proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins (95,112,133). Protein expression of Bcl-2 (95,135,136), Bcl-xL (135), IAPs (54, 135), and survivin (135) were reduced by GTC treatment of prostate cancer cells. EGCG and ECG treatment caused hyperphosphorylation of Bcl-xL, leading to cytochrome c release, and caspase activation in serumstarved prostate cancer cells (137). GTCs inhibited the phosphorylation of Bad at Ser 112 and Ser 136, lowering cancer cell resistance to apoptosis (135). Apoptosis occurred through the stabilization of p53 by the p-14 mediated downregulation of MDM2 and the inhibition of NFκB, decreasing the expression of Bcl-2 (95). EGCG treatment also modulated the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. The expression of extrinsic apoptotic pathway proteins, the DR4 death receptor, Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), and FLICE-inhibitory protein (FLIP) were increased in TRAIL-resistant LNCaP cells treated with EGCG (135). Other apoptotic pathways may be affected by GTCs. In DU-145 cells, apoptosis is induced with no alteration of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Bad and may be related to increases in reactive oxygen species and direct mitochondrial depolarization (98). Treatment also caused downregulation of an inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (ID2), a dominant antiretinoblastoma (Rb) helix-loop-helix protein, in which the expression reduced apoptosis and increased survival of prostate cancer cells (134).

Cell cycle arrest, growth suppression, and apoptosis are intricately linked (138–141), and this relationship has implications for cancer therapy (140). Cell cycle arrest and growth suppression by GTCs is related to induction of apoptosis (98,108); reciprocally, apoptosis is an active inhibitor of cell proliferation in prostate cancer cells (48,65). Cell cycle arrest in prostate cancer cells is irreversible; the cells are unable to repair damages, forcing them into apoptosis (89). The processes are linked by proteins active in the regulation of both cell-cycle and apoptosis (138,139), including p21, p53, and Bcl-2 family members (140,141), all of which are modified in prostate cancer cells as the result of GTC treatment.

In addition to cell-cycle related and antiapoptotic proteins, oncogenes play a major role in the suppression of apoptosis during carcinogenesis. Nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) is an oncogenic transcription factor involved in the regulation of inflammatory genes that plays an essential role in the regulation of normal and cancer cell apoptosis (142). NFκB is constitutively expressed in prostate cancer cells, PIN, and prostate cancer tissues (143,144) and regulates androgen-independent growth of prostate cancer cells (145,146). Negative regulation of NFκB activity triggered a change in Bax-Bcl-2 ratios and resulted in prostate cancer cell apoptosis (147,148). EGCG reduced NFκB p65 expression in prostate cancer cells (95,133,149) and phosphorylated NFκB p65 was reduced in TRAMP mice treated with GTCs (150). Treatment with a combination of GTCs and soy mitigated inflammation and prostate cancer cell death; increased IκBα reduced NFκB p50 expression and transcriptional activity in a Noble rat model (54). The combination of GTCs and COX-2 inhibitors reduced phosphorylated NFκB p65 in vitro and in vivo (61). Receptor activator of NFκB (RANK) regulates NFκB, subsequently upregulating Bcl-xL (151,152) and its cytoplasmic domain activates NFκB inducing kinase (NIK) (153). RANK and NIK were elevated in prostate carcinogenesis of TRAMP mice and were inhibited by GTC infusion (150). Another possible mechanism of EGCG-induced NFκB modulation is through caspase activation (49,133). In LNCaP cells, EGCG caused caspase activation, which resulted in the cleavage of the NFκB p65 subunit and caused apoptosis (133).

Suppression of Carcinogenesis and Progression

It is critical to suppress prostate carcinogenesis in the premalignant and early stages because as tumors progress, they eventually become hormone-refractory, leading to more aggressive tumors with poorer prognosis (154). GTCs suppress prostate carcinogenesis and progression in laboratory and clinical studies. GTC treatment of prostate cancer cells resulted in the inhibition of anchorage-independent growth (52,155) of prostate cancer cells. EGCG (96,108,110) and GTC treatment (39,51,58,109,127,156) suppressed carcinogenesis and progression in vivo. Additionally, GTCs and Polyphenon E suppressed tumor growth (56,61,96,99,111,112) and significantly regressed established tumors (111,112) in rodent models. A combination of soy and tea suppressed carcinogenesis and progression in rodents (56). It is important to note that GTC-induced suppression was more effective when it occurred during earlier stages of prostate carcinogenesis in animal models (108,127,157). In clinical studies, GTC capsules given to men with HGPIN significantly reduced their progression to prostate cancer (70), and this effect was found to be long-lasting (71).

Inhibition of Metastasis

Metastasis is the major cause of cancer deaths (158); therefore, inhibiting metastasis of prostate cancer tumors may serve as an effective strategy against disease progression (135). GTCs suppressed prostate cancer invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. GTCs reduced prostate cancer cell migration in vitro (102). EGCG treatment reduced cell invasion and migration in TRAIL-induced human prostate cancer cells and TRAMP C1 mouse cells (106,135). GTCs, EGCG, and Polyphenon E treatment in rodent models reduced prostate cancer metastasis compared to control mice (39,96). A combination of GT infusion and soy caused a similar inhibition of metastasis in mice (56). GTCs suppress metastasis by inhibiting the expression of invasion and angiogenic factors. The invasion of prostate cancer cells through the basement membrane (BM) and extracellular matrix (ECM) is one of the early events in the metastatic spread of prostate cancer (159). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9 (160), degrade EMC components and contribute to prostate cancer tumor progression (161–163). EGCG and GTC treatment inhibited MMP-2 (102,106,149,161–163) in prostate cancer cells and TRAMP mice (124), whereas MMP-9 was reduced in prostate cancer cells (149) and rodent models (58). EGCG decreased the expression of MMPs-2, −3, and −9 and increased the MMP inhibitor, TIMP-1, in LNCaP cells sensitized to TRAIL-induced apoptosis, resulting in decreased migration potential, cell invasion, and cell cytotoxicity (135). EGCG-induced repression of MMP-2 and −9 was mediated by inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation, p38 pathways, and inhibition of the transcription factors, c-jun and NFκB (149). Urokinase also known as urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) promotes prostate metastasis by mediating plasminogen activation (164,165). The growth inhibitory effects of EGCG and GTCs may be due to reduced uPA expression in prostate cancer cells (135) and TRAMP mice (124).

Angiogenesis is required for tumor growth, survival, and metastasis (166,167). Vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in angiogenesis (168) and prostate cancer (4,169,170). EGCG treatment decreased VEGF expression in LNCaP cells sensitized to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (135). Oral infusion of GTCs resulted in reduced VEGF expression in TRAMP mice (124) and in the tumors of athymic mice injected with human prostate cancer cells (58,112). A combination of GTCs and COX-2 inhibitors also reduced VEGF levels in the tumors of mice injected with prostate cancer cells (61). Prostate cancer patients given short-term daily doses of Polyphenon E had significant decreases in serum levels of VEGF (72). Angiopoietin 1/2 are angiogenic growth factors required for formation of mature blood vessels (171). EGCG treatment decreased angiopoietin 1/2 expression in LNCaP cells sensitized to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (135). Ultimately, these effects may be attributed to apoptosis, which is the endpoint target for GTC-induced chemoprevention of prostate cancer (98,172). Cancer cell death subsequently leads to the inhibition of prostate cancer development, progression, and metastasis (39).

GTCs exert anticancer activity on prostate cancer cells via 6 major mechanisms (Table 1), by altering a variety of different proteins (Table 2). Other pathways and proteins, in addition to those mentioned above, are also involved in GTC chemoprevention of prostate carcinogenesis (Table 3). Gene expression profiles of prostate cancer cells (134,173), TRAMP mouse tumors (174), and human prostate biopsies (175) treated with and without GTC treatment have highlighted the plethora of different regulatory pathways affected by GTC treatment, many of which have the potential to be therapeutic targets for prostate cancer prevention and treatment (134,173–175). Notably, proteins involved in prostate cancer are regulated by signal transduction pathways that are also altered during carcinogenesis and affected by GTC treatment (50,96,105,108,124,127,136, 149,176,177).

TABLE 1.

Mechanisms of green tea catechin chemoprevention on prostate cancer cells and tissues

| Major mechanisms of GTC chemoprevention |

References |

|---|---|

| Proteasome inhibition | 52, 85 |

| Cell cycle arrest | 48, 52, 60, 85, 89, 90 |

| Reduced cell proliferation | 39, 50, 51, 54, 56, 58–61, 65, 89, 90, 95–101, 103–110, 135, 193 |

| Apoptosis | 39, 48, 51, 52, 59–61, 65, 89, 90, 95–98, 100, 105, 106, 108, 112, 133–135, 194 |

| Suppression of carcinogenesis/progression | 39, 51, 56, 58, 70*, 71*, 96, 102, 108–110, 127, 156 |

| Suppression of invasion/metastasis | 39, 56, 96, 106, 135 |

Clinical studies.

TABLE 2.

Proteins affected by green tea catechin treatment in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies by major mechanisms

| Protein type | Protein | Decreased expression | Increased expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome inhibition | |||

| p21+ | 89,90,95 | ||

| P27+ | 52,85,89 | ||

| IκBα+ | 52,85,133 | ||

| Bax+ | 52,54,61,95,112,135,150 | ||

| Cell cycle regulation | CDK2 | 89 | |

| CDK4 | 89 | ||

| CDK6 | 89 | ||

| Cyclin D | 89 | ||

| Cyclin E | 89 | ||

| MDM2 | 95 | ||

| p14 | 95 | ||

| p16 | 89 | ||

| p18 | 89 | ||

| p53+ | 90,95 | ||

| Ph-Rb | 134 | ||

| Cell proliferation | |||

| ID2 | 134 | ||

| MDM7 | 109 | ||

| Apoptosis | |||

| Ph-Bad Ser 112 | 135 | ||

| Ph-Bad Ser 136 | 135 | ||

| Bak | 135 | ||

| Bcl-2 | 54,95,112,135,150 | ||

| Bcl-xL | 135 | ||

| Clusterin | 51 | ||

| DR4 | 135 | ||

| FADD | 135 | ||

| FLIP | 135 | ||

| IAP | 54,135 | ||

| Smac/Diablo | 135 | ||

| Survivin | 135 | ||

| XIAP | 135 | ||

| Metastasis | |||

| Invasion | E-cadherin | 156 | |

| MMP2 | 102,106,124,135,149 | ||

| MMP3 | 135 | ||

| MMP9 | 58,124,135,149 | ||

| Mts1 (S100A4) | 156 | ||

| TIMP1 | 135 | ||

| uPA | 124,135 | ||

| Angiogenesis | Angiopoietin 1/2 | (135) | |

| VEGF | 58,61,72*,112,124,135 |

Proteins that play roles in multiple mechanisms of GTC chemoprevention.

Clinical studies. CDK indicates cyclin-dependent kinase; DR4, death receptor 4; FADD, fas-associated protein with death domain; FLIP, FLICE-inhibitory proteins; IAP, inhibitor of apoptosis; ID2, inhibitor of DNA-binding protein; MDM7, marker minichromosome maintenance protein 7; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; Ph, phosphorylated; Rb, retinoblastoma protein; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

TABLE 3.

Proteins affected by green tea catechin treatment in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies by other mechanisms

| Protein type | Protein | Decreased expression | Increased expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen pathway | |||

| AR | 99, 104, 108, 175 | ||

| DHT | 56 | ||

| PSA | 56, 61, 72, 99, 102, 112 | ||

| Testosterone | 56, 113 | ||

| Enzymes | |||

| FAS | 97 | ||

| MDSOD | 60 | ||

| ODC | 155 | ||

| Gene modification and expression | |||

| DNMT | 107, 192, 195 | ||

| GST | 107, 190* | ||

| HDAC 1–3 | 107 | ||

| MBD1/4 | 107 | ||

| MeCP2 | 107 | ||

| Growth factors | |||

| IGF-1 | 39, 61, 72, 90, 108, 124, 127 | ||

| IGFR-1 | 108 | ||

| Ph-IGFR-1 | 105 | ||

| IGFBP-3 | 61, 72* | 11, 39, 124, 127 | |

| HGH | 72 | ||

| HGH/c-Met | 176 | ||

| Inflammation | |||

| COX-2 | 100, 108 | ||

| IL-1β | 54 | ||

| IL-6 | 54 | ||

| iNOS | 108 | ||

| Osteopontin | 135 | ||

| TNFα | 54 | ||

| Signal transduction | |||

| AKT | |||

| Ph-AKT | 124, 127, 136, 176 | ||

| ERK1/2 | 176 | 50 | |

| Ph-ERK1/2 | 96, 108, 124, 127, 149 | 50, 136 | |

| k-ras | 101 | ||

| MAPK | 108 | ||

| Ph-MAPK | 105 | ||

| p38 | 137 | ||

| Ph-p38 | 149 | ||

| PI3K | 136 | ||

| PI3K p85 | 124, 127 | ||

| SphK1 | 96 | ||

| Transcription factors | |||

| c-jun | 149 | ||

| HIF-1α | 187 | ||

| phIκBα | 146 | ||

| IKKα | 146 | ||

| NFκB p50+ | 54 | ||

| NFκB p65+ | 95, 133, 149 | ||

| Ph-NFκB p65+ | 150 | ||

| PPARγ | 61 | ||

| RANK | 150 | ||

| NIK | 150 | ||

| Sp-1 | 104 | ||

| Stat-3 | 150 |

Proteins that play roles in multiple mechanisms of GTC chemoprevention.

Clinical studies. AR indicates androgen receptor; COX-2, xyclooxygenase-2; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinases; FAS, fatty acid synthase; GST, glutathionine-S-transferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HGH, human growth hormone; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGFR, insulin-like growth factor receptor; IGFBP, insulin-like growth factor binding protein; IκBa, inhibitor of κBα; IL, interleukin;

iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; MDSOD, manganese superoxide dismutase; MBD, methyl-CpG-binding protein; meCP2, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B; NIK, NFkB-inducing kinase; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase; P13K, phosphoinositide kinase-3; Ph, phosphorylated, PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB; SphK, sphingosine kinase; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor; Stat, signal transducer and activator of transcription; Sp, specificity protein.

A NOVEL MODEL OF GTC CHEMOPREVENTION ON PROSTATE CANCER CELLS

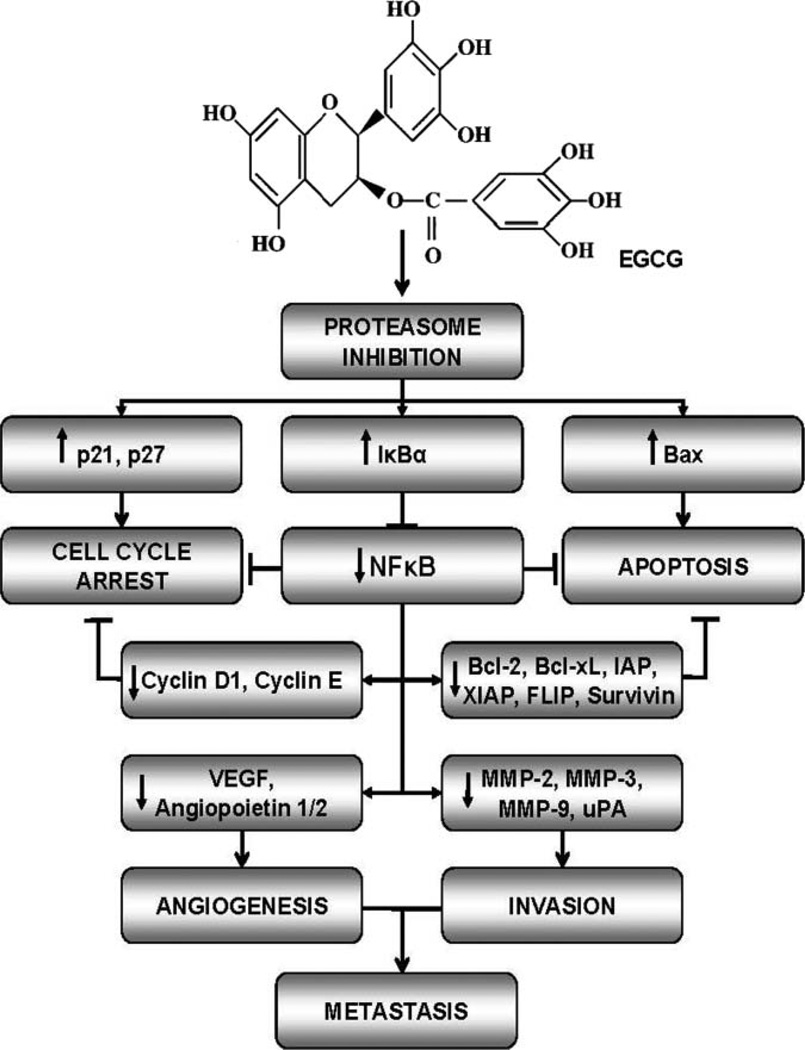

Models of GTC chemopreventive activities against cancer include many interrelated mechanisms (178–180). Models of GTC chemopreventive effects on prostate cancer focus on the link between cell cycle, apoptosis, and invasion factors, MMP-2, MMP-9, and VEGF (172), or cell cycle arrest and subsequent apoptosis (89,95). Although a plethora of mechanisms of green tea activity in malignant prostate cancer cells have been proposed (7,38,172,181,182), comprehensive attempts to recreate a somewhat sequential molecular pathway by which GTCs modulate prostate carcinogenesis have been rare. Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, we propose a novel model in which the 6 major mechanisms of GTC—chemoprevention, proteasome inhibition, cell cycle arrest, inhibition of cell proliferation, apoptosis, suppression of carcinogenesis, and progression and inhibition of metastasis—work simultaneously and in concert through the NFκB pathway to exert chemopreventive action on prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1). GTC-induced inhibition of chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome (52,85) results in the accumulation proteasome targets p21 (89,90,95), p27 (52,85,89), Bax (52,54,61,95,112,135,150), and IκBα (52,85). The accumulation of cell cycle regulators p21 and p27 result in G1 cell cycle arrest (48,52,60,85,89,90), whereas the accumulation of the proapoptotic protein, Bax, contributes to cell apoptosis. The oncogenic transcription factor, NFκB, is downregulated (54,95,133,149), presumably by the elevation of IκBα, its intrinsic inhibitor. This results in the reduced expression of NFκB target genes, antiapoptotic, Bcl-xL (135) and Bcl-2 (54,95,112,135,150), cell cycle regulators, cyclin D (89) and cyclin E (89), and metastasis-related genes, VEGF (58,61,72,112,124,135), angiopoietin 1/2 (135), MMPs (58,102,106,124,135,149), and uPA (124,135) seen in GTC-treated prostate cancer cells and tissues. Reductions in cyclins D and E, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL further drive the processes of cell cycle arrest, decreased cell proliferation, and apoptosis, respectively. Additionally, the reduction in metastasis-related genes inhibits tumor cell invasion and metastasis. The cumulative effect of these mechanisms is the reduction of the number of premalignant and cancer cells, leading to the inhibition of prostate cancer progression and metastasis. GTC-induced mechanisms work to combat the hallmarks of cancer. These mechanisms affect the expression of a variety of GTC-target proteins (Tables 2–3), many of which serve as surrogate or intermediate prostate cancer biomarkers (183–186). The mechanisms regulating GTC-target gene expression in prostate cancer chemo-prevention have not been fully elucidated. GTCs may act on upstream regulators of target proteins, such as NFkB. GTC-target proteins and their upstream regulators may also be further regulated by modulation of hormone pathways, enzymes, gene expression and transcription factors, growth factors, inflammatory factors, and/or signal transduction pathways (Table 5). This is the first model to suggest that proteasome inhibition may act as the primary mechanism that triggers the remaining mechanisms (cell cycle arrest, inhibition of cell proliferation, apoptosis, suppression of carcinogenesis/progression and inhibition of metastasis) of GTC-induced chemoprevention of prostate cancer. Other mechanisms and proteins play a role in the chemopreventive activity of GTCs on prostate cancer cells and tissues and more mechanisms and proteins are yet to be identified.

FIG. 1.

Cumulative molecular model for the mechanism of green tea catechins in the chemoprevention of prostate cancer. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is the most potent catechin present in green tea. Green tea catechins (GTCs), particularly EGCG, inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome resulting in the accumulation proteasome targets p21, p27, Bax, and IκBα. The accumulation of cell cycle regulators, p21 and p27, cause cell cycle arrest; while the accumulation of the proapoptotic protein, Bax, contributes to cancer cell apoptosis. Additionally, the elevation of IκBα expression inhibits the translocation of the oncogenic protein, NFκB, to the nucleus, resulting in reduced expression of its target genes, Bcl-xL and Bcl-2, cyclin D and cyclin E, VEGF, and MMPs. Reductions in these proteins further drive the processes of cell cycle arrest, decreased cell proliferation, and apoptosis, as well as the inhibition of tumor cell invasion and metastasis, respectively. The cumulative effect of these mechanisms leads to the inhibition of prostate cancer progression and metastasis. All proteins shown are affected by GTC treatment of prostate cancer cells and tissues in laboratory and/or clinical studies. The up arrow indicates induction; while the down arrow indicates reduction in protein expression upon GTC treatment. FLIP indicates FLICE-inhibitory proteins; IκBα, inhibitor of IκBα; IAP, inhibitor of apoptosis; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; XIAP, x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis.

TABLE 5.

Green tea catechin phase II clinical trials in men with premalignant prostate lesions or prostate cancer

| Disease state | n | GTC | Dosage | Treatment time | Conclusions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced HRPC | 42 | GT powder | 6 g/day | 1–4 mo | Limited antineoplastic activity | 69 |

| HRPC | 19 | GTE capsules | 250 mg, 2/day | 4 wk–5 mo | Minimal clinical activity against HRPC | 68 |

| HGPIN | 60 | GTP capsules | 200 mg, 3/day | 1–12 mo | Chemopreventive action against premalignant prostate lesions | 70 |

| HGPIN | 60 | GTP capsules | 200 mg, 3/day | 1–12 mo | Chemopreventive action against premalignant lesions is long lasting | 71* |

| CaP | 26 | PPE | 800 mg, 1/day | 1 wk–8 mo | Clinical significance for treatment of CaP | 72 |

Two-yr follow-up of 70.

CaP indicates prostate cancer; GT, green tea; GTC, green tea catechin; GTE, green tea extract; GTP, green tea polyphenols; HGPIN, high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; HRPC, hormone-resistant prostate cancer; PPE: Polyphenon E.

We hypothesize that proteasome inhibition directly targets the NFκB pathway and is a primary step in GTC-induced chemoprevention activities in prostate cancer cells. Several lines of evidence support our hypothesis: 1) GTC-induced proteasome inhibition and GTC treatment resulted in the accumulation of NFkB inhibitor IκBα (52,85,133) and decreased NFkB expression (54,95,133,149); 2) other markers of proteasome inhibition, p21, p27, and Bax, were also affected by GTCs and play a role in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in GTC-treated prostate cancer cells; and 3) NFκB target genes involved in carcinogenesis, including cyclin D1, Cdk2, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, IAPs, c-FLIP, survivin, MMPs, VEGF, uPA, and iNos (183–186), are also reduced by GTC treatment (Tables 4 and 5).

TABLE 4.

In vitro green tea catechin studies conducted on prostate cancer cells

| Cell lines | GTC | Dosage | IC50 | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DU-145 | EGCG | 80 µg/mL | N.R. | Induction of apoptosis | 48 |

| LNCaP, DU-145, PC-3 | EC, ECG, EGC, EGCG, GTP | 0, 1, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 200, 400 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 65 |

| 0, 1, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 200, 400 µg/mL | |||||

| LNCaP | ECG, EGCG | 1, 10 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 101 |

| GTE | 10, 100 µg/mL | ||||

| GTP | 0.02%, 0.2% | ||||

| LNCaP | GTP | 0, 20, 40, 60 µg/mL | N.R. | Inhibition of testosterone-induced ODC activity/expression, colony formation | 155 |

| LNCaP, DU-145 | EGCG | 0, 10, 2 0, 40, 80 µg/mL | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation G1 arrest | 90 |

| Induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Induction of p21, p53 | |||||

| LNCaP | EGCG, GCG, | 0, 10, 20 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 104 |

| GTP | Inhibition of AR, SP1 activity | ||||

| DU-145 | EC | 0, 10, 100 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of proliferation | 98 |

| EGC | 88 µM | Apoptosis | |||

| ECG | 60 µM | Induction of ROS formation | |||

| EGCG | 74 µM | Mitochondrial depolarization | |||

| LNCaP, DU-145 | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 40 µg/mL | N.R. | Induction of p21 p27, p16, p18 | 89 |

| Inhibition of cyclin D1/E, Cdk 2, 4, 6 | |||||

| LNCaP | EC, EGCG | 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 150 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation Apoptosis | 97 |

| Inhibition of FAS activity | |||||

| PC-3 | EGCG | 5, 10, 20, 50 µM | N.R. | Reactivation of RARβ | 192 |

| LNCaP | EGCG | 20, 40, 60, 80 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of proliferation | 95 |

| Induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Induction of p53, p21, p14, Bax | |||||

| Inhibition of NFκB, MDM2 | |||||

| LNCaP, PC-3 | EGCG | 0, 10, 30, 50, 80, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 500 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of proliferation Oxidative stress | 59 |

| LNCaP, DU-145 | EGCG | 0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of PSA, MMP2/9 activation | 102 |

| DU-145 | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 40 µg/mL | N.R. | Inhibition of j-induced MMP2/9 | 149 |

| Inhibition of Ph ERK1/2, p38, c-Jun | |||||

| Inhibition of NFκB, AP-1 activation | |||||

| LNCaP, DU-145 | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 40 µg/mL | N.R. | Inhibition of P13K/AKT levels Induction of ERK1/2 | 136 |

| LNCaP | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 40 µg/mL | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 133* |

| Induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Induction of caspases | |||||

| Inhibition of NFκB activity | |||||

| Primary PEC | EGCG | 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 µg/mL | N.D. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 51 |

| PNT1A | 0, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350 µg/mL | 83.6 µM | Induction of clusterin expression | ||

| PC-3 | 0, 140, 160, 180, 200, 220 µg/mL | 202.3 µM | Inhibition of pro-caspases 3, 8 | ||

| TRAMP-C1 | EGCG | 0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 µM | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 106 | |

| Induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Inhibition of MMP-2, 9 activity | |||||

| Inhibition of cell invasion | |||||

| PC-3, PC-3ML | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 40 µg/mL | N.R. | Induction of HIF-1α activity | 187 |

| Inhibition of HPH activity | |||||

| LNCaP, PC-3 | EGCG | 0, 10, 25, 50, 100 µM | N.R. | Induction of apoptosis in stimulated cells | 100 |

| Inhibition of COX-2 in stimulated cells | |||||

| HH870, DU-145 | EGCG | 0, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 103 |

| NRP-152, NRP-154 | EGCG | 10, 20, 30, 40 µM | Inhibition of cell proliferation | ||

| Induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Induction of cell cycle arrest | |||||

| CWR22v1, LNCaP | EGCG | 10, 20, 40 µmol/L | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 61 |

| Induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Induction of Bax | |||||

| Inhibition of NFκB, PPAR-γ, Bcl-2 | |||||

| PC-3 | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 80 µM | 38.95 µM | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 50 |

| Induction of Ph ERK1/2 | |||||

| LNCaP | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 40, µM | N.R. | Sensitizes cells to TRAIL-induce apoptosis | 135 |

| LNCaP, DU-145, | EGCG | 0, 10, 20, 30, µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 105 |

| PC-3 | Induction of apoptosis | ||||

| Inhibition of IGF-induced cell growth | |||||

| Sensitizes DHT-treated cells to growth inhibition and apoptosis | |||||

| LNCaP sublines | EGCG | 0, 20, 40, 80 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of cell proliferation | 99 |

| Inhibition of AR, PSA | |||||

| LNCaP, DU-145 | EGCG | 20–120 µM | N.R. | Induction of apoptosis | 134 |

| GTE | 3% | Inhibition of ID2, Ph Rb | |||

| DU-145 | EC, ECG, EGC, EGCG | 2.5, 5, 10 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of c-Met receptor, Ph AKT, ERK | 176 |

| Altered lipid raft structure/function | |||||

| Inhibition of HGH-induced scattering, motility, and invasion | |||||

| LNCaP, DU-145, MDA PCA 2b | EGCG | 5, 10, 20 µM | N.R. | Inhibition of gene-specific hypermethlyation | 107 |

| PPE | 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 µg/mL | Inactivation of S100P | |||

| Acetylation of histones | |||||

| Inhibition of HDAC 1, 2, 3 | |||||

| PC-3 | EGCG | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 µM | 75 µM | Reduction in SphK1 | 96 |

| PPE | 0, 25, 50, 75 µM | 70 µM | activity |

Data reported but not shown. AR indicates androgen receptor; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; EC, epicatechin; ECG, epicatechin gallate; EGC, epigallocatechin; EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; FCM, fibroblast conditioned medium; GTE, green tea extract; GTP, green tea polyphenols; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; ID2, inhibitor of DNA binding 2; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase;PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RARβ, Retinoic acid receptor; Rb, retinoblastoma; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MDM2, murine double minute 2; MnSOD, manganese superoxide dismutase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; N.D., not determined; N.R., not reported; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B; PEC, prostate epithelial cells; Ph, phosphorylated; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PPE, Polyphenon E, SphK1, sphingosine kinase-1.

NFκB as a Target of GTC Chemopreventive Activities During Prostate Carcinogenesis

Studies indicate that NFκB plays a critical role in carcinogenesis and that its inhibition suppresses carcinogenesis of human cancer (185). NFκB plays an important role in prostate carcinogenesis (143,144,147,148) and it is posited as a potential therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer (150,185). NFκB protein activation results in the transcription of genes involved in all 6 of the hallmarks of cancer (183) and contributes to prostate carcinogenesis by inducing proteins involved in cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, suppression of apoptosis, and metastasis (183–185). NFκB target genes are also reduced by GTC treatment of prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (reviewed within). In addition to the accumulation of IκBα (52,54,85,150), GTC treatment regulates NFκB and subsequent target gene expression by repressing activating phosphorylation of NFκB (61,150), reducing IKKα expression (146) and caspase cleavage of the p65 sub-unit (133), and reducing other key signaling factors, including RANK and NIK (150). These findings are suggestive that NFκB is at least 1 of the major signaling pathways through which GTCs exert their chemopreventive mechanisms on prostate cancer cells. The observation that GTC-induced proteasome inhibition accumulates IκBα and that GTCs reduce the expression NFκB target genes indicates that regulation of the NFκB pathway of by GTC-induced proteasome inhibition may play a primary role in GTC chemopreventive activities in prostate cancer cells.

CONCLUSION

GTCs are promising agents for the chemoprevention of prostate cancer in the clinical setting (68,70–72,190). GTCs are most effective against early stage prostate carcinogenesis in laboratory (106,108,127) and clinical studies (70,71), and are attractive chemopreventive agents because of low toxicity (24,43–47) and specificity to transformed and malignant cells (48–52). The use of GTCs for prostate cancer chemoprevention is not without challenges. In vitro (Table 4) and in vivo (7) dosages have varied greatly by study and are not easily translated to clinical studies. Additionally, studies indicate that caution should be used when supplementing with high concentrations of GTCs because of unintended responses (187,188) and inhibitory actions on other compounds (57). Despite these challenges, several clinical trials have been carried out with GTCs (Table 5). Cell culture and animal models suggest that GTCs exert chemopreventive action against prostate cancer cells by targeting mechanisms essential to cancer cell growth, progression, and metastasis (7,38,172,181,182,189). We propose a novel model in which GTCs, particularly EGCG, exert chemopreventive effects on prostate cancer through 6 major mechanisms that work simultaneously and dependently, largely driven through proteasome inhibition induced regulation of the NFκB pathway. GTCs cause proteasome inhibition and subsequent cell cycle arrest, growth suppression, and ultimately apoptosis in prostate cancer cells and tissues. GTC-induced apoptosis results in the reduction of cancer cell dissemination, causing the inhibition of prostate cancer development, progression, and metastasis (Fig. 1). The six primary mechanisms of GTC-induced chemopreventive action on prostate cancer cells are seen consistently across laboratory and clinical studies. The pathways by which these mechanisms are regulated and activated do, however, vary by cell type and context, which is to be expected in the multifaceted processes pertaining to cell homeostasis and carcinogenesis.

Understanding the anticarcinogenic activities and mechanisms of GTCs is essential to developing appropriate therapeutic modalities for the prevention of prostate cancer. Although GTCs act through distinct cell cycle and apoptotic pathways, the cumulative chemopreventative effect appears to be attributed to their well-coordinated ensemble rather than a single pathway (89,172,178). More studies are needed to gain insight into GTC-induced mechanisms of prostate cancer prevention and develop the most appropriate clinical settings in which to use green tea for chemoprevention (27,180). Research focused on the onco-genes, transcription factors, growth factors, cell cycle regulatory, and other factors affected by GTCs will inform these mechanistic studies (180). Efforts should continue to fill the lack of data that makes it difficult to extrapolate results from in vitro to in vivo to clinical studies (19,27,64,191).

Bridging this gap will require more in vitro studies to confirm the mechanisms mentioned in this review and to identify new mechanisms and potential biomarkers of GTC chemoprevention in prostate cancer cells and tissues. Because of the context-specific differences inherent in biological systems, it critical that these mechanisms are tested in a variety of prostate cancer cell lines that differ by origin, hormone status, aggressiveness, and other factors. Only then can these mechanisms be tested in vivo with rodent models, validated in human phase II and phase III clinical studies, and appropriately applied to chemoprevention therapies (40).

Additionally, transitioning from the use of individual GTCs, to purified GTC preparations, such as Polyphenon E, may provide a standardized compound that may more accurately reflect human tea consumption, deliver the maximum amount of GTCs without caffeine side effects, and provide more insight to GTC-induced chemopreventive mechanisms. Our laboratory studies are currently focusing on testing and refining the cumulative model of GTC chemoprevention in prostate cancer cells as a first step to fully elucidate the complex mechanism of GTC chemoprevention of prostate cancer in its entirety.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Center to Reduce Health Disparities, National Institute of Health–National Cancer Institute supplement to RO1CA122060.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bostwick DG, Qian J. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:360–379. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein JI, Herawi M. Prostate needle biopsies containing prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical foci suspicious for carcinoma: implications for patient care. J Urol. 2006;175:820–834. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00337-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraft A, Weindel K, Ochs A, Marth C, Zmija J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in the sera and effusions of patients with malignant and nonmalignant disease. Cancer. 1999;85:178–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohamed MA, Greif PA, Diamond J, Sharaf O, Maxwell P, et al. Epigenetic events, remodelling enzymes and their relationship to chromatin organization in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic adenocarcinoma. BJU Int. 2007;99:908–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannuci E. Epidemiologic characteristics of prostate cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:1766–1777. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JJ, Bailey HH, Mukhtar H. Green tea polyphenols for prostate cancer chemoprevention: a translational perspective. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynder EL, Rose DP, Cohen LA. Nutrition and prostate cancer: a proposal for dietary intervention. Nutr Cancer. 1994;22:1–10. doi: 10.1080/01635589409514327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jian L, Xie LP, Lee AH, Binns CW. Protective effect of green tea against prostate cancer: a case-control study in southeast China. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:130–135. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson WG. Agents in development for prostate cancer prevention. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:1541–1554. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Division of Cancer Prevention and Control: Clinical development plan: tea extracts, green tea polyphenols, epigallocatechin gallate. J Cell Biochem. 1996;26:236–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balentine DA, Wiseman SA, Bouwens LC. The chemistry of tea flavonoids. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1997;37:693–704. doi: 10.1080/10408399709527797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn WS, Yoo J, Huh SW, Kim CK, Lee JM, et al. Protective effects of green tea extracts (polyphenon E and EGCG) on human cervical lesions. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:383–390. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bushman JL. Green tea and cancer in humans: a review of the literature. Nutr Cancer. 1998;31:151–159. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higdon JV, Frei B. Tea catechins and polyphenols: health effects, metabolism, and antioxidant functions. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2003;43:89–143. doi: 10.1080/10408690390826464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelloff GJ, Boone CW, Crowell JA, Nayfield SG, Hawk E, et al. Risk biomarkers and current strategies for cancer chemoprevention. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1996;25:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang CS, Lambert JD, Ju J, Lu G, Sang S. Tea and cancer prevention: molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;224:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borrelli F, Capasso R, Russo A, Ernst E. Systematic review: green tea and gastrointestinal cancer risk. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:497–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert JD, Yang CS. Cancer chemopreventive activity and bioavailability of tea and tea polyphenols. Mutat Res. 2003;523–524:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang W, Binns CW, Jian L, Lee AH. Does the consumption of green tea reduce the risk of lung cancer among smokers? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:17–22. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun CL, Yuan JM, Koh WP, Yu MC. Green tea, black tea and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1310–1315. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolcott CG, King WD, Marrett LD. Coffee and tea consumption and cancers of the bladder, colon and rectum. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:137–145. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar N, Titus-Ernstoff L, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Anic G, et al. Tea consumption and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:341–345. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow HH, Hakim IA, Vining DR, Crowell JA, Cordova CA, et al. Effects of repeated green tea catechin administration on human cytochrome P450 activity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2473–2476. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MJ, Maliakal P, Chen L, Meng X, Bondoc FY, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1025–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinshilboum RM, Otterness DM, Szumlanski CL. Methylation pharmacogenetics: catechol O-methyltransferase, thiopurine methyltransferase, and histamine N-methyltransferase. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:19–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. Tea polyphenols: prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1698S–1702S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1698S. discussion, 1703S–1694S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sang S, Lambert JD, Ho CT, Yang CS. The chemistry and biotransformation of tea constituents. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan JM, Sun C, Butler LM. Chapter 8. Tea and cancer prevention: epidemiological studies. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thakur VS, Gupta K, Gupta S. The chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic potentials of tea polyphenols. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011 Apr 5; doi: 10.2174/138920112798868584. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton-Miller JM. Antimicrobial properties of tea (Camellia sinensis L.) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2375–2377. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katiyar S, Mukhtar H. epidemiologic and experimental studies. Int J Oncol. 1996;8:221–238. doi: 10.3892/ijo.8.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao S, Kao YH, Hiipakka RA. Green tea: biochemical and biological basis for health benefits. Vitam Horm. 2001;62:1–94. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)62001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gullett NP, Ruhul Amin AR, Bayraktar S, Pezzuto JM, Shin DM, et al. Cancer prevention with natural compounds. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:258–281. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelloff GJ, Lieberman R, Steele VE, Boone CW, Lubet RA, et al. Agents, biomarkers, and cohorts for chemopreventive agent development in prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57:46–51. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dou QP. Molecular mechanisms of green tea polyphenols. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:827–835. doi: 10.1080/01635580903285049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenwald P, Kelloff GJ. The role of chemoprevention in cancer control. IARC Sci Publ. 1996:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan N, Adhami VM, Mukhtar H. Review: green tea polyphenols in chemoprevention of prostate cancer: preclinical and clinical studies. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:836–841. doi: 10.1080/01635580903285056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta S, Hastak K, Ahmad N, Lewin JS, Mukhtar H. Inhibition of prostate carcinogenesis in TRAMP mice by oral infusion of green tea polyphenols. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10350–10355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171326098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenwald P. Clinical trials in cancer prevention: current results and perspectives for the future. J Nutr. 2004;134:3507S–3512S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3507S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan N, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Cancer chemoprevention through dietary antioxidants: progress and promise. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:475–510. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan N, Mukhtar H. Tea polyphenols for health promotion. Life Sci. 2007;81:519–533. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chow HH, Cai Y, Alberts DS, Hakim I, Dorr R, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic study of tea polyphenols following single-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chow HH, Cai Y, Hakim IA, Crowell JA, Shahi F, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of green tea polyphenols after multiple-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E in healthy individuals. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3312–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chow HH, Hakim IA, Vining DR, Crowell JA, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Effects of dosing condition on the oral bioavailability of green tea catechins after single-dose administration of Polyphenon E in healthy individuals. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4627–4633. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ullmann U, Haller J, Decourt JD, Girault J, Spitzer V, et al. Plasma-kinetic characteristics of purified and isolated green tea catechin epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) after 10 days repeated dosing in healthy volunteers. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2004;74:269–278. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.74.4.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ullmann U, Haller J, Decourt JP, Girault N, Girault J, et al. A single ascending dose study of epigallocatechin gallate in healthy volunteers. J Int Med Res. 2003;31:88–101. doi: 10.1177/147323000303100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmad N, Feyes DK, Nieminen AL, Agarwal R, Mukhtar H. Green tea constituent epigallocatechin-3-gallate and induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1881–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.24.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad N, Gupta S, Mukhtar H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate differentially modulates nuclear factor kappaB in cancer cells versus normal cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;376:338–346. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albrecht DS, Clubbs EA, Ferruzzi M, Bomser JA. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) inhibits PC-3 prostate cancer cell proliferation via MEK-independent ERK1/2 activation. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;171:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caporali A, Davalli P, Astancolle S, D’Arca D, Brausi M, et al. The chemopreventive action of catechins in the TRAMP mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis is accompanied by clusterin over-expression. Car-cinogenesis. 2004;25:2217–2224. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith DM, Wang Z, Kazi A, Li LH, Chan TH, et al. Synthetic analogs of green tea polyphenols as proteasome inhibitors. Mol Med. 2002;8:382–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sartippour MR, Shao ZM, Heber D, Beatty P, Zhang L, et al. Green tea inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induction in human breast cancer cells. J Nutr. 2002;132:2307–2311. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu A, Bruno RS, Lohr CV, Taylor AW, Dashwood RH, et al. Dietary soy and tea mitigate chronic inflammation and prostate cancer via NFkappaB pathway in the Noble rat model. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;22:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nair S, Barve A, Khor TO, Shen GX, Lin W, et al. Regulation of Nrf2-and AP-1-mediated gene expression by epigallocatechin-3-gallate and sulforaphane in prostate of Nrf2-knockout or C57BL/6J mice and PC-3 AP-1 human prostate cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:1223–1240. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou JR, Yu L, Zhong Y, Blackburn GL. Soy phytochemicals and tea bioactive components synergistically inhibit androgen-sensitive human prostate tumors in mice. J Nutr. 2003;133:516–521. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.2.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen X, Yu H, Shen S, Yin J. Role of Zn2+ in epigallocatechin gallate affecting the growth of PC-3 cells. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2007;21:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roomi MW, Ivanov V, Kalinovsky T, Niedzwiecki A, Rath M. In vivo antitumor effect of ascorbic acid, lysine, proline and green tea extract on human prostate cancer PC-3 xenografts in nude mice: evaluation of tumor growth and immunohistochemistry. In Vivo. 2005;19:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu HN, Yin JJ, Shen SR. Growth inhibition of prostate cancer cells by epigallocatechin gallate in the presence of Cu2+ J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:462–466. doi: 10.1021/jf035057u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morrissey C, Brown M, O’Sullivan J, Weathered N, Watson RW, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and bicalutamide cause growth arrest and apoptosis in NRP-152 and NRP-154 prostate epithelial cells. Int J Urol. 2007;14:545–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adhami VM, Malik A, Zaman N, Sarfaraz S, Siddiqui IA, et al. Combined inhibitory effects of green tea polyphenols and selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on the growth of human prostate cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1611–1619. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujiki H. Two stages of cancer prevention with green tea. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1999;125:589–597. doi: 10.1007/s004320050321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen L, Lee MJ, Li H, Yang CS. Absorption, distribution, elimination of tea polyphenols in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1045–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moyers SB, Kumar NB. Green tea polyphenols and cancer chemoprevention: multiple mechanisms and endpoints for phase II trials. Nutr Rev. 2004;62:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paschka AG, Butler R, Young CY. Induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines by the green tea component, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Lett. 1998;130:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suganuma M, Okabe S, Sueoka N, Sueoka E, Matsuyama S, et al. Green tea and cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res. 1999;428:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pisters KM, Newman RA, Coldman B, Shin DM, Khuri FR, et al. Phase I trial of oral green tea extract in adult patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1830–1838. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choan E, Segal R, Jonker D, Malone S, Reaume N, et al. A prospective clinical trial of green tea for hormone refractory prostate cancer: an evaluation of the complementary/alternative therapy approach. Urol Oncol. 2005;23:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jatoi A, Ellison N, Burch PA, Sloan JA, Dakhil SR, et al. A phase II trial of green tea in the treatment of patients with androgen independent metastatic prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1442–1446. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bettuzzi S, Brausi M, Rizzi F, Castagnetti G, Peracchia G, et al. Chemoprevention of human prostate cancer by oral administration of green tea catechins in volunteers with high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia: a preliminary report from a one-year proof-of-principle study. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1234–1240. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brausi M, Rizzi F, Bettuzzi S. Chemoprevention of human prostate cancer by green tea catechins: two years later. A follow-up update. Eur Urol. 2008;54:472–473. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McLarty J, Bigelow RL, Smith M, Elmajian D, Ankem M, et al. Tea polyphenols decrease serum levels of prostate-specific antigen, hepatocyte growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor in prostate cancer patients and inhibit production of hepatocyte growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in vitro. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:673–682. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee MJ, Wang ZY, Li H, Chen L, Sun Y, et al. Analysis of plasma and urinary tea polyphenols in human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang CS, Chen L, Lee MJ, Balentine D, Kuo MC, et al. Blood and urine levels of tea catechins after ingestion of different amounts of green tea by human volunteers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang CS, Lee MJ, Chen L. Human salivary tea catechin levels and catechin esterase activities: implication in human cancer prevention studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Henning SM, Aronson W, Niu Y, Conde F, Lee NH, et al. Tea polyphenols and theaflavins are present in prostate tissue of humans and mice after green and black tea consumption. J Nutr. 2006;136:1839–1843. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dou QP, Landis-Piwowar KR, Chen D, Huo C, Wan SB, et al. Green tea polyphenols as a natural tumour cell proteasome inhibitor. Inflammopharmacology. 2008;16:208–212. doi: 10.1007/s10787-008-8017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blagosklonny MV, Wu GS, Omura S, el-Deiry WS. Proteasomedependent regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:564–569. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nicholson DW, Ali A, Thornberry NA, Vaillancourt JP, Ding CK, et al. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37–43. doi: 10.1038/376037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pagano M, Tam SW, Theodoras AM, Beer-Romero P, Del Sal G, et al. Role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in regulating abundance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Science. 1995;269:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7624798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li B, Dou QP. Bax degradation by the ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent pathway: involvement in tumor survival and progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3850–3855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070047997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nam S, Smith DM, Dou QP. Ester bond-containing tea polyphenols potently inhibit proteasome activity in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13322–13330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang CS. Tea and health. Nutrition. 1999;15:946–949. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sandhu C, Slingerland J. Deregulation of the cell cycle in cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2000;24:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gupta S, Hussain T, Mukhtar H. Molecular pathway for (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of human prostate carcinoma cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;410:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]