Abstract

Background:

Young athletes have more nutritional needs than other adolescents because of physical activity and physical development. Optimal athletic performance results from a combination of factors including training, body composition, and nutrition. Despite the increased interest in nutrition and use of dietary supplements to enhance performance, some athletes might be consuming diets that are less than optimal. In wrestling it is common practice to optimize one's body composition and body weight prior to a competition season. This often includes a change in dietary intake or habits.

Methods:

Twenty-eight wrestlers, between the ages of 17 and 25 years, participated in this study. Dietary intakes of micro and macro nutrients were collected by face-to-face interview, structured food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Dietary intake of energy, carbohydrates, fats and proteins and micronutrients was evaluated.

Results:

Mean intakes of energy, carbohydrates, proteins and fat were higher than recommended dietary allowances (RDA). The mean intakes of all vitamins and minerals were higher than the RDAs in these wrestlers, except for vitamin D, biotin, zinc, iodine, chrome and molybdenum.

Conclusions:

On the basis of our results, nutritional education should be given to these subjects and their families for promoting healthy eating habits.

Keywords: Athletes, dietary behavior, nutritional status, wrestlers

INTRODUCTION

Optimal athletic performance results from a combination of factors including training, body composition, and nutrition.[1] Nutritional needs are higher during adolescence than at any other time in the lifecycle, regardless of the level of activity, because of rapid gain in height and weight.[2,3] Young athletes have more nutritional needs than other adolescents because of physical activity and physical development, especially those athletes who exercise strenuously in order to maximize their performance.[4]

Comprehensive reassessment of nutrient intakes and dietary behaviors is warranted at the present time because there is a strong emphasis on the importance of nutrition and body composition to enhance performance in young athletes' programs. Also young athletes have become more competitive, particularly boys, and this increased pressure to win could motivate athletes to alter their body weight and diet to improve their performance.[1]

Despite the increased interest in nutrition and use of dietary supplements to enhance performance[5–7] some athletes might be consuming diets that are less than optimal.[8,9] Some athletes purposefully restrict their dietary intake to lose weight and maintain low body weight.[9,10]

It has generally been reported that energy intake of male athletes is high enough to prevent micro and macro nutrient deficiency, although wrestlers have been found to have low nutrient intake.[11]

Wrestlers periodically engage in higher degree of dietary restraint than other athletes because wrestling depends on the weight of the participating athlete.[10] In the wrestling it is common practice to optimize one's body composition and body weight prior to a competition season. This often includes a change in dietary intake or habits.[12]

Weight regulation practices among wrestlers have been proven to have negative effects on health parameters such as on nutritional status, hormonal status and immune function.[13]

There has been very little research on health and nutrition issues in wrestlers, especially in Iran. Thus the purpose of this study was to assess the nutritional status and eating behavior of young male wrestlers and to determine if these athletes are at greater risk of nutrient deficiency than other athletes.

METHODS

Twenty-eight wrestlers, between the ages of 17 and 25 years, participated in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all of them. All athletes were playing for different wrestling clubs in Isfahan.

Dietary intakes of micro and macro nutrients were collected by face-to-face interview with structured food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). A dietitian provided verbal and written instructions on how to record food consumption. The use of food models helped the subjects to measure the quantity of foods.

The food frequency questionnaire categorized food items into five food groups: 1) mixed dishes (cooked or canned); 2) grains (different types of bread, cakes, biscuits and potato); 3) dairy products (dairies, butter and cream); 4) fruits and vegetables; and 5) miscellaneous food items and beverages (including sweets, fast foods, nuts, desserts and beverages) and was designed to obtain qualitative information about the usual food consumptions patterns with an aim to assess the frequency with which certain food items or groups are consumed.

The frequency response categories for each food item were defined separately in a row against the food list. For all frequency response categories, we mentioned the portion size repeatedly, to simplify responding. The number of frequency response categories was not constant for all foods. For foods consumed infrequently, we preferred to omit the high-frequency categories, while for common foods with high consumption, the number of multiple choice categories increased.

In addition to energy, dietary intake of carbohydrates, fats and proteins was evaluated. For the above, total grams and percentage of total energy were calculated.

The minerals that were calculated were iron, magnesium, zinc, manganese, iodine, calcium and selenium and vitamins were vitamin B1, B2, C, Niacin, Folic Acid and Biotin.

RESULTS

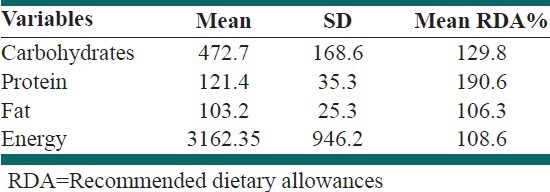

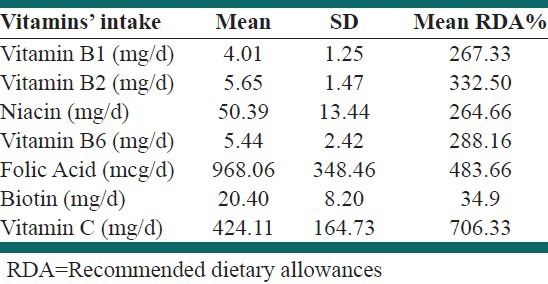

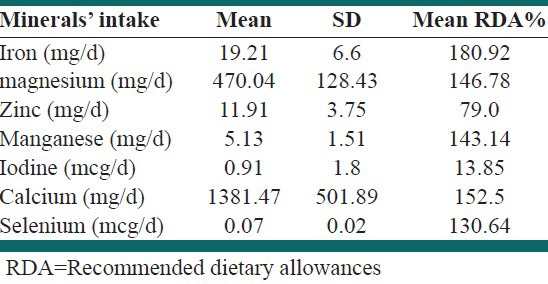

Table 1 shows the energy and macronutrients' intake of the athletes. Mean intakes of energy, carbohydrates, proteins and fat were higher than recommended dietary allowances (RDA) value (108.6, 129.8, 190.6 and 106.3 percent, respectively). The mean intakes of all vitamins were higher than the RDAs in these wrestlers [Table 2], except for vitamin D, biotin (70.7 and 34.9% of RDAs, respectively). In addition, the mean intakes of all minerals were higher than the RDAs [Table 3], except for zinc, iodine, chrome and molybdenum (79, 13.85, 57.9 and 44.5% of RDAs, respectively).

Table 1.

The mean intakes of energy and macronutrients in wrestlers

Table 2.

The mean intakes of some vitamins in wrestlers

Table 3.

The mean intakes of some minerals in wrestlers

Rice, bread, potato, meat, pulses, eggs, milk, milk products, butter and vegetable oils provided 83% of total energy intake, 81% of proteins, 75% of carbohydrates and 62% of lipids. The food intake of these participants was mainly based on these foods.

DISCUSSION

The current study is the first assessment of the nutrition status of young male wrestlers in Iran. The findings of this study identify important nutrition inadequacies in young wrestlers. Although there is a paucity of research on these athletes with which our findings can be compared, the result of this investigation can be used to inform future research in this population and development of specific nutrition guideline.

Energy balance

The results from this study reveal mean daily energy intake of wrestlers is 108% of RDA. Our results are not similar to those reported by other authors, who found suboptimal relative energy intake in adolescent water polo, volleyball and netball athletes.[14] Although it is tempting to conclude that the players were not in energy balance in those studies, under-reporting of dietary intake has been previously identified in adolescent athletes.[15] Similar to our study Pamela S showed male athletes had adequate energy intake even if the nutrient density of their diet is low.[1]

Macronutrient intake

Carbohydrates are the primary fuel used in wrestling and a daily intake of 5-7 g/kg has been suggested for young wrestlers to meet the needs of activity, as well as recovery from training.[16,17] In the current study mean daily carbohydrate intake of athletes was 129% of RDA which does not concur with previously reported intakes in adult female players,[18] adolescent male soccer athletes,[19] and adolescent female athletes in other sports.[14]

Suboptimal carbohydrate intake could result in premature muscle glycogen depletion during training or competition, as well as insufficient glycogen resynthesis after exercise, leading to compromised performance.[20]

The results from this study reveal that the mean daily fat intake of wrestlers is 106.3% of RDA. Our athletes may benefit from dietary counseling because many researchers share the opinion that high-fat diets hamper performance and may provoke many health problems.[21,22] Dietary fat helps with the absorption of critical fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids. It provides also an essential fuel source and increases growth needs of adolescents.[2] Our data in dietary fat intake are not similar to other studies in female figure skaters, gymnasts, runners and female track and field athletes.[23,24] Fat consumption of athletes in those studies was less than the RDA.

In this study athletes had a much higher protein intake than the RDA. Protein intake of 1.2-1.7 g/kg/day has been suggested as a guideline for athletes and those involved in intermittent high-intensity sport to support muscle protein synthesis and repair.[25] Protein is a critical macronutrient needed in adolescent athletes to help accommodate rapid growth and development, stimulate lean-tissue growth and provide a potential energy source for performance.[2,25]

The most prevalent inadequate micronutrient intakes in this study were for zinc, iodine, chrome and molybdenum, vitamin D and biotin. These results suggest that our athletes are less likely to consume fresh fruits and vegetables. Biotin is a critical vitamin B involved in energy metabolism, tissue repair and maintenance.[26] Vitamin D is involved in the development, maintenance and repair of bone—inadequate intake could place young athletes at risk for lower bone mineral density and stress for fracture.[26]

Other studies have reported that significant proportions of athletes on a particular sports team have inadequate intakes of micronutrients. Among female athletes participating in crew,[27] swimming,[28] field hockey,[28] gymnastics,[5] and basketball,[29–31] low intakes of calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, folate and vitamin D were observed. Similar deficiencies in vitamin and mineral intake have been reported in wrestlers, particularly during the competitive season.[27]

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of our results, nutritional education should be given to these subjects and their families for promoting healthy eating habits. Also, we recommend that the nutritional status of these wrestlers should be corrected for achieving optimal performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the athletes who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Hinton PS, Sanford TC, Davidson MM, Yakushko OF, Beck NC. Nutrient intakes and dietary behaviors of male and female collegiate athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004;14:389–405. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.14.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrie HJ, Stover EA, Horswill CA. Nutritional concerns for the child and adolescent competitor. Nutrition. 2004;20:620–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbloom CA, Loucks AB, Ekblom B. Special populations: The female player and the youth player. J Sports Sci. 2006;24:783–93. doi: 10.1080/02640410500483071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papadopoulou SK, Papadopoulou SD, Gallos GK. Macro- and micro-nutrient intake of adolescent Greek female volleyball players. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12:73–80. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.12.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghiasvand R, Askari Gh, Malekzadeh J, Hajishafiee M, Daneshvar P, Akbari F, et al. Effects of six weeks of β-alanine Administration on VO2 max, Time to Exhaustion and Lactate Concentrations in Physical Education Students. Int J Prev Med. 2012;8:559–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askari G, Ghiasvand R, Karimian J, Feizi A, Paknahad Z, Sharifirad G, et al. Does quercetin and vitamin C improve exercise performance, muscle damage, and body composition in male athletes? J Res Med Sci. 2012;4:328–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghiasvand R, Djalali M, Djazayery SA, Keshavarz SA, Hosseini M, Jani N, et al. Effect of Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) and Vitamin E on the blood levels of inflammatory markers, antioxidant enzymes, and lipid peroxidation in iranian basketball players. Iran J Public Health. 2010;1:15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchner EM, Lewis RD, O'Connor PJ. Bone mineral density and dietary intake of female college gymnasts. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:543–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Hourani HM, Atoum MF. Body composition, nutrient intake and physical activity patterns in young women during Ramadan. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:906–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettersson S, Pipping Ekstrom M, Berg CM. The food and weight combat. A problematic fight for the elite combat sports athlete. Appetite. 2012;59:234–42. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Short SH, Short WR. Four-year study of university athletes' dietary intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 1983;82:632–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enns MP, Drewnowski A, Grinker JA. Body composition, body size estimation, and attitudes towards eating in male college athletes. Psychosom Med. 1987;49:56–64. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horswill CA, Scott JR, Dick RW, Hayes J. Influence of rapid weight gain after the weigh-in on success in collegiate wrestlers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:1290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heaney S, O'Connor H, Gifford J, Naughton G. Comparison of strategies for assessing nutritional adequacy in elite female athletes' dietary intake. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010;20:245–56. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.20.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caccialanza R, Cameletti B, Cavallaro G. Nutritional intake of young Italian high-level soccer players: underreporting is the essential outcome. J Sports Sci Med. 2007;6:538–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke LM, Kiens B, Ivy JL. Carbohydrates and fat for training and recovery. J Sports Sci. 2004;22:15–30. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000140527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maughan RJ, Shirreffs SM. Nutrition and hydration concerns of the female football player. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:i60–3. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.036475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark M, Reed DB, Crouse SF, Armstrong RB. Pre- and post-season dietary intake, body composition, and performance indices of NCAA division I female soccer players. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003;13:303–19. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.13.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iglesias-Gutierrez E, Garcia-Roves PM, Rodriguez C, Braga S, Garcia-Zapico P, Patterson AM. Food habits and nutritional status assessment of adolescent soccer players. A necessary and accurate approach. Can J Appl Physiol. 2005;30:18–32. doi: 10.1139/h05-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rico-Sanz J, Zehnder M, Buchli R, Dambach M, Boutellier U. Muscle glycogen degradation during simulation of a fatiguing soccer match in elite soccer players examined noninvasively by 13C-MRS. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:1587–93. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costill DL, Coyle E, Dalsky G, Evans W, Fink W, Hoopes D. Effects of elevated plasma FFA and insulin on muscle glycogen usage during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1977;43:695–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decombaz J, Arnaud MJ, Milon H, Moesch H, Philippossian G, Thelin AL, et al. Energy metabolism of medium-chain triglycerides versus carbohydrates during exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1983;52:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00429018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rankinen T, Fogelholm M, Kujala U, Rauramaa R, Uusitupa M. Dietary intake and nutritional status of athletic and nonathletic children in early puberty. Int J Sport Nutr. 1995;5:136–50. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.5.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiura K, Suzuki I, Kobayashi K. Nutritional intake of elite Japanese track-and-field athletes. Int J Sport Nutr. 1999;9:202–12. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.9.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boisseau N, Vermorel M, Rance M, Duche P, Patureau-Mirand P. Protein requirements in male adolescent wrestlers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;100:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American College of Sports Medicine; American Dietetic Association; Dietitians of Canada. Joint Position Statement: Nutrition and athletic performance. American College of Sports Medicine, American Dietetic Association, and Dietitians of Canada. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:2130–45. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200012000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steen SN, McKinney S. Nutrition assessment of college wrestlers. Physician Sports Med. 1986;14:100–16. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1986.11709226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tilgner SA, Schiller MR. Dietary intakes of female college athletes: The need for nutrition education. J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89:967–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowak RK, Knudsen KS, Schulz LO. Body composition and nutrient intakes of college men and women basketball players. J Am Diet Assoc. 1988;88:575–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moin P, Khalighinejad N, Yusefi A, Farajzadegan Z, Barekatain M. Converting three general-cognitive function scales into persian and assessment of their validity and reliability. Int J Prev Med. 2011;2:82–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatami H. History of rabies in traditional medicine's resources and Iranian research studies: On the CccasiOn of the World Rabies Day (September 28, 2012) Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:593–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]