Abstract

Sternal fractures are predominantly associated with deceleration injuries and blunt anterior chest trauma. Sternal trauma must be carefully evaluated by monitoring of vital parameters and it is of paramount importance that concomitant injuries are excluded. Nevertheless, routine admission of patients with isolated sternal fractures for observation is still common in today's practice, which is often unnecessary. This article aims to describe the prognosis, the recommended assessment and management of patients with sternal fractures, to help clinicians make an evidence-based judgment regarding the need for hospitalization.

Keywords: Fracture, management, sternum, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Sternal fractures are associated with deceleration injuries and blunt anterior chest trauma (incidence of 3-6.8% in motor vehicle collisions).[1] Mechanisms of injury associated with sternal fractures are classified into either direct or indirect trauma.[2] Direct trauma include deceleration injuries and blunt anterior chest trauma.[1,3] The introduction of seat-belt legislation and shoulder restraints has resulted in an increased frequency of these injuries.[1,3] Direct impact sports, vehicle-to-pedestrian collisions, falls, and assaults account for the majority of the remaining cases.[4] Indirect forces may cause insufficiency fractures, stress fractures and pathological fractures. Insufficiency fractures occur spontaneously in patients with severe thoracic kyphosis and in those with osteoporosis. Elderly patients, post-menopausal women and patients on long-term steroid therapy are at particular risk.[5] Stress fractures have also been noted in athletes who undertake repetitive upper body exercise without history of acute trauma.[6]

Studies show that the current management of sternal fractures in several centers does not comply with available evidence, particularly in cases of isolated sternal fractures.[7] The purpose of this article is to describe the prognosis, the recommended assessment and investigations for patients sustaining sternal fractures, to help clinicians evaluate the need for hospital admission.

PROGNOSIS AND COMPLICATIONS

Sternal fractures can either occur in isolation, or with other associated injuries. Prognosis is excellent for isolated sternal fractures, with most patients recovering completely over a period of weeks (average 10.4 weeks).[8] The overall mortality of sternal fractures is 0.7%.[1] However, two-thirds of sternal fractures have concomitant injuries with an associated mortality ranging from 25-45 %.[9] These injuries can be subdivided into 3 categories: i) Soft tissue injuries ii) Injuries to the chest wall and iii) Injuries to the spine, appendages and cranium. Chest wall injuries include rib fractures, flail chest and sternoclavicular dislocation. Soft tissue injuries include pneumothoraces, hemothoraces, cardiac tamponade, myocardial and pulmonary contusions, as well as injuries to the abdomen and diaphragm.[9] Thoracic spine compression fractures, as well as[4,10] trauma to the head, neck, and extremities are also common. There is a significant correlation between displaced or unstable sternal fractures and pulmonary injuries, pericardial effusions, spinal and rib fractures.[11]

Complications following sternal fractures include short and long term sequelae. Short term complications include chest pain post-injury, which has a mean duration of 8 to 12 weeks for all age groups.[8] It is the predominant symptom post-injury in patients with isolated sternal fractures, with more than two-thirds of patients requiring management with analgesia alone.[11] Apprehension due to pain can impair ventilation, predisposing to chest infection. This is due to the involvement of the sternum in all motions of the chest cage, particularly those involving respiration and coughing. Long term complications include non-union, and painful pseudarthrosis may occur with the development of a false joint or overlap deformities. This may require surgical correction.[12] Predisposing factors for delayed or impaired union include advanced age, osteoporosis, diabetes, and corticosteroid therapy. Contributing factors include mechanical and anatomical factors such as instability and poor bone-to-bone contact. Abnormalities in calcium, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone may also impact fracture healing due to their vital role in bone metabolism.[13] Rare sequelae of sternal fractures include osteomyelitis, sternal abscess and mediastinitis. Risk factors for a post-traumatic mediastinal abscess include hematoma formation, intravenous drug abuse, and a staphylococcal infection source [Table 1a-b].[14]

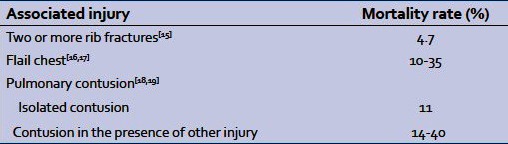

Table 1a.

Mortality of injuries associated with sternal fractures

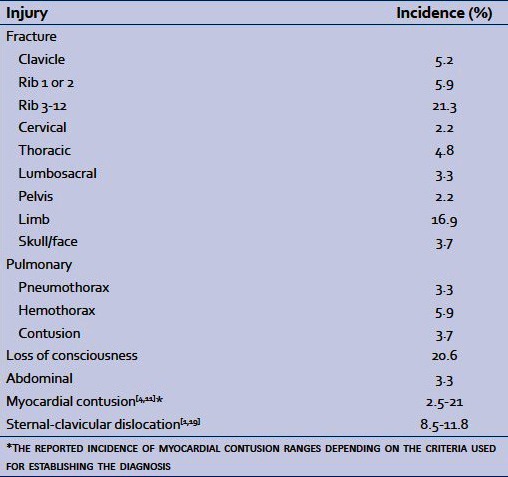

Table 1b.

Incidence of injuries associated with sternal fractures[1]

INVESTIGATIONS

A lateral chest radiograph remains the gold standard investigation in diagnosing sternal fractures, as the fracture and any displacement or dislocation occurs in the sagittal plane.[20] An antero-posterior chest radiograph is useful in detecting concomitant injuries, which include rib fractures, pulmonary contusions, and hemothoraces/pneumothoraces, as well as a widened mediastinum which may be indicative of other coexistent pathology [Table 2a].[21] The detection of any of the former warrants further investigation by multi-slice spiral CT. Axial CT is considered to be inferior to radiography for sternal fracture diagnosis, as CT cuts may miss transverse sternal fractures.[22] Ultrasonography detects sternal fractures with equal sensitivity as plain radiography, or may be considered diagnostically superior.[23] Limiting factors including inter-operator variability, render it less acceptable as the first-line imaging modality. It is superior in the detection of rib fractures and pleural effusions; however it cannot identify the degree of fracture displacement.[24] While bone scintigraphy is superior diagnostically, and will identify fractures missed in plain radiographs,[25] it is not widely available.

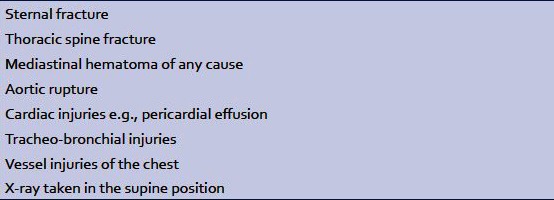

Table 2a.

Causes of a widened mediastinum[21]

Pulse oximetry should be obtained on clinical presentation, as well as serial electrocardiograms, observing for features indicative of myocardial contusion. These include an unexplained sinus tachycardia, arrhythmias, conduction disturbances, or ST-segment changes.[2] Echocardiography should be considered in patients with other concomitant injuries.[26] It provides a direct view of wall motion abnormalities, and is considered an excellent tool in the detection of acute myocardial contusion [Table 2b].[27,28] In patients with painful chest wall injuries transthoracic echocardiographic access may be limited. In these patients, transoesophageal echocardiography is recommended, as well as in cases of suspected lesions to the great vessels or if the transthoracic images are suboptimal.[28,29] If myocardial contusion is suspected, cardiac biomarkers must be measured.[30] A poor correlation has been reported between elevated CK-MB and cardiac sequelae.[31] Serum cardiac troponins (troponin I and T) have been found to be highly specific to myocardial injury.[32] The optimal timing of blood sampling for troponin assays has not yet been determined to diagnose a cardiac contusion. If troponin I or T concentrations are within reference ranges on admission, a second measurement after 4-6 hrs is necessary to reliably exclude myocardial injury.[33]

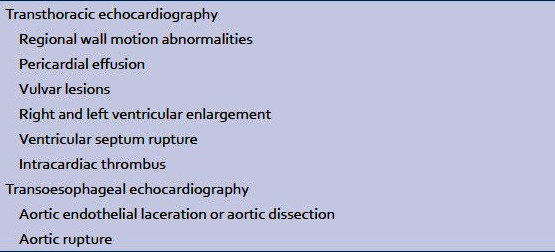

Table 2b.

Echocardiographic findings in acute cardiac contusion[28]

MANAGEMENT

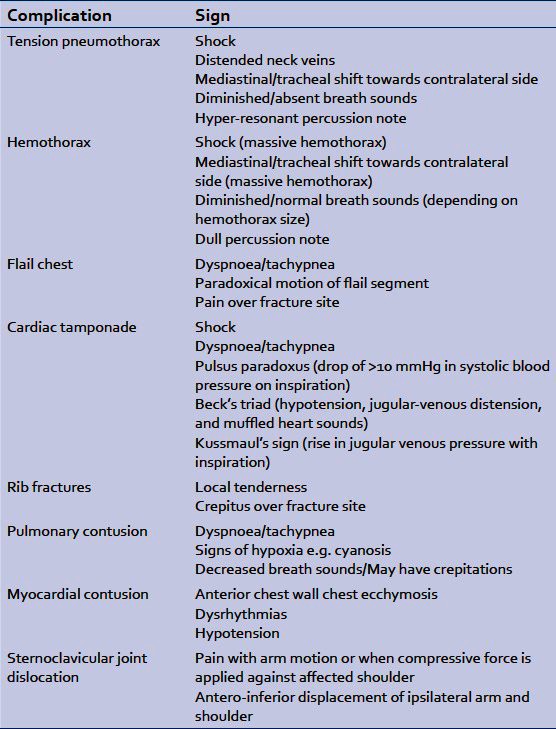

In the acute setting, the patient should initially be resuscitated according to ATLS guidelines.[34] This involves establishing a patent airway and cervical spine control if injury is suspected. The patient's breathing and circulation should be assessed, and any life-threatening conditions should be identified and immediately treated during the primary survey. These include tension pneumothorax, massive hemothorax, open pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade and flail chest [Table 3].[34,35] The patient's Glasgow Coma Scale score should be assessed, as well as the neurovascular status of the upper limbs if a sternal fracture is suspected. Finally, the patient should be exposed to check for any bruising, bleeding or injuries elsewhere. The secondary survey includes obtaining a history from the patient, or a collateral source focusing on events leading to injury and on the past medical and drug history. The head, spine, back and extremities should be examined for trauma. Chest injuries identified on secondary survey include rib fractures, pulmonary contusion, simple pneumothorax, simple hemothorax, blunt aortic injury, and blunt myocardial injury [Table 3].

Table 3.

Patients with sternal fractures present with acute sternal pain, aggravated by deep breathing and coughing, associated with localized tenderness and signs of respiratory insufficiency. These include tachypnea, cyanosis, and the use of accessory muscles for ventilation. Inspection of the anterior chest wall may show ecchymosis or contusion with or without a step deformity. Palpation may reveal a fracture related crepitus.[35]

The required investigations for suspected sternal fractures should be ordered. The degree of fracture displacement should be ascertained, as complete displacement is associated with serious cardiac or pulmonary injury.[20] Hemodynamically unstable patients, those with suspected myocardial contusion, or those with ECG findings indicative of it, should be evaluated with biomarkers of cardiac injury, echocardiography and continuous monitoring. ICU admission (if unstable) may also be necessary.[30] Patients with suspected myocardial contusion include those with anterior chest wall ecchymosis, sternal tenderness, complaints of sternal or substernal chest pain, as well as deformity.[30] Stable patients with isolated sternal fractures, a normal ECG and cardiac enzymes, are expected to have a benign course, and can be discharged home with analgesics and follow-up within the first 24 hrs.[36]

Operative fixation may be indicated for displaced or unstable fractures. These may cause debilitating chest pain or be associated with flail chest, compromising pulmonary or cardiac function. Sternal fixation can be effectively performed using sternal wires or formal osteosynthesis using plate and screws.[37–39]

CONCLUSION

Sternal fractures are not uncommon injuries. They may be associated with major injuries to thoracic organs, with potentially fatal sequelae. In the acute setting, management includes resuscitation according to ATLS guidelines, and treatment of any coexistent injuries. After exclusion of other concomitant injuries, patients with isolated sternal fractures can be safely discharged home within the first 24 hrs, provided cardiac enzymes (troponin) and ECG findings are normal. Routine hospital admission is therefore unnecessary for all patients with sternal fractures, and is warranted in those with significant associated injuries. Other factors which may justify hospitalization include major co-morbidities, high-impact trauma, severely displaced fractures, inadequate pain control, or insufficient domestic support.[40]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brookes JG, Dunn RJ, Rogers IR. Sternal fractures: A retrospective analysis of 272 cases. J Trauma. 1993;35:46–54. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Tarnowsky G., VII Contrecoup fracture of the sternum. Ann Surg. 1905;41:252–64. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190502000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hills MW, Delprado AM, Deane SA. Sternal fractures: Associated injuries and management. J Trauma. 1993;35:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knobloch K, Wagner S, Haasper C, Probst C, Krettek C, Otte D, et al. Sternal fractures occur most often in old cars to seat-belted drivers without any airbag often with concomitant spinal injuries: Clinical findings and technical collision variables among 42,055 crash victims. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:444–50. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horikawa A, Miyakoshi N, Kodama H, Shimada Y. Insufficiency fracture of the sternum simulating myocardial infarction: Case report and review of the literature. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007;211:89–93. doi: 10.1620/tjem.211.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertsen K, Kristensen O, Vejen L. Manubrium sterni stress fracture: An unusual complication of non-contact sport. Br J Sports Med. 1996;30:176–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.30.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hossain M, Ramavath A, Kulangara J, Andrew JG. Current management of isolated sternal fractures in the UK: Time for evidence based practice? A cross-sectional survey and review of literature. Injury. 2010;41:495–8. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Oliveira M, Hassan TB, Sebewufu R, Finlay D, Quinton DN. Long-term morbidity in patients suffering a sternal fracture following discharge from the A and E department. Injury. 1998;29:609–12. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck RJ, Pollak AN, Rahm SJ. Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett; 2005. Thoracic trauma. Intermediate emergency care and transportation of the sick and injured. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holderman HH. Fracture and dislocation of the sternum: Report of three cases. Ann Surg. 1928;88:252–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192808000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy-Shapira A, Levi I, Khoda J. Sternal fractures: A red flag or a red herring? J Trauma. 1994;37:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosse A, Grosse C, Steinbach L, Anderson S. MRI findings of prolonged post-traumatic sternal pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:423–9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes GL, Kakar S, Vora S, Morgan EF, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Stimulation of fracture-healing with systemic intermittent parathyroid hormone treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:120–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuschieri J, Kralovich KA, Patton JH, Horst HM, Obeid FN, Karmy-Jones R. Anterior mediastinal abscess after closed sternal fracture. J Trauma. 1999;47:551–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liman ST, Kuzucu A, Tastepe AI, Ulasan GN, Topcu S. Chest injury due to blunt trauma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:374. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaillard M, Herne C, Mandin , Raynaud P. Mortality prognosis factors in chest injury. J Trauma. 1990;30:93–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciraulo DL, Elliott D, Mitchell KA, Rodriguez A. Flail chest as a marker for significant injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:466–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirvis SE. Diagnostic imaging of acute thoracic injury. Semin ultrasound CT MR. 2004;25:156–79. doi: 10.1016/j.sult.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dee PM. The radiology of the chest trauma. Rad Clin North Am. 1992;30:291–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Garrel T, Ince A, Junge A, Schnabel M, Bahrs C. The sternal fracture: Radiographic analysis of 200 fractures with special reference to concomitant injuries. J Trauma. 2004;57:837–44. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000091112.02703.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saab M, Kurdy NM, Birkinshaw R. Widening of the mediastinum following a sternal fracture. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51:256–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huggett JM, Roszler MH. CT findings of sternal fracture. Injury. 1998;29:623–6. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin W, Yang DM, Kim HC, Ryu KN. Diagnostic values of sonography for assessment of sternal fractures compared with conventional radiography and bone scans. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1263–8. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.10.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engin G, Yekeler E, Guloglu R, Acunas B, Acunas G. US versus conventional radiography in the diagnosis of sternal fractures. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:296–9. doi: 10.1080/028418500127345280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erhan Y, Solak I, Kocabas S, Sozbilen M, Kumanlioglu K, Moral AR. The evaluation of diagnostic accordance between plain radiography and bone scintigraphy for the assessment of sternum and rib fractures in the early period of blunt trauma. Ulus Travma Derg. 2001;7:242–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiener Y, Achildiev B, Karni T, Halevi A. Echocardiogram in sterna fracture. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:403–5. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.24463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King RM, Mucha P, Jr, Seward JB, Gersh BJ, Farnell MB. Cardiac contusion: A new diagnostic approach utilizing two-dimensional echocardiography. J Trauma. 1983;23:610–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sybrandy KC, Cramer MJ, Burgersdijk C. Diagnosing cardiac contusion: Old wisdom and new insights. Heart. 2003;89:485–9. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.5.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karalis DG, Victor MF, Davis GA, McAllister MP, Covalesky VA, Ross JJ, Jr, et al. The role of echocardiography in blunt chest trauma: Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Trauma. 1994;36:53–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiu WC, D'amelio LE, Jeffrey S. Hammond. Sternal fractures in blunt chest trauma: A practical algorithm for management. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:252–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller KD, Shatney CH. Creatine phosphokinase-MB assays in patients with suspected myocardial contusion: Diagnostic test or test of diagnosis. J Trauma. 1988;28:58–63. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198801000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins JN, Cole FJ, Weireter LJ, Riblet JL, Britt LD. The usefulness of serum troponin levels in evaluating cardiac injury. Am Surg. 2001;67:821–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swaanenburg JC, Klaase JM, DeJongste MJ, Zimmerman KW, ten Duis HJ. Troponin I, troponin T, CKMB-activity and CKMB-mass as markers for the detection of myocardial contusion in patients who experienced blunt trauma. Clin Chem Acta. 1998;272:171–81. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. 8th ed. USA: American College of Surgeons; 2008. Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors, Student Course Manual (ATLS) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cubasch H, Degiannis E. The deadly dozen of chest trauma. J Contin Med Educ. 2004;22:369–72. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouldman JW, Miller RS. Sternal fracture: A benign entity? Am Surg. 1997;63:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bar I, Friedman T, Rudis E, Shargal Y, Friedman M, Elami A. Isolated sternal fracture – a benign condition? Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:105–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson LD, Carter R, Hinshaw DB. Surgical significance of sternal fracture. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1962;114:443–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hendrickson SC, Koger KE, Morea CJ, Aponte RL, Smith PK, Levin LS. Sternal plating for the treatment of sternal nonunion. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:512–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sommer C. Fixation of transverse fractures of the sternum and sacrum with the locking compression plate system: Two case reports. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:487–90. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000149873.99394.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]