Abstract

Spontaneous pneumobilia without previous surgery or interventional procedures indicates an abnormal biliary-enteric communication, most usually a cholelithiasis-related gallbladder perforation. Conversely, choledocho-duodenal fistulisation (CDF) from duodenal bulb ulcer is currently exceptional, reflecting the low prevalence of peptic disease. Combination of clinical data (occurrence in middle-aged males, ulcer history, absent jaundice and cholangitis) and CT findings including pneumobilia, normal gallbladder, adhesion with fistulous track between posterior duodenum and pancreatic head) allow diagnosis of CDF, and differentiation from usual gallstone-related biliary fistulas requiring surgery. Conversely, ulcer-related CDF are effectively treated medically, whereas surgery is reserved for poorly controlled symptoms or major complications.

Keywords: Biliary fistula, duodenal ulcer, peptic ulcer, pneumobilia

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 53-years-old Iraqi immigrant with longstanding ulcer history complained of severe epigastric pain. He denied current medical treatment and previous surgery. Acute phase reactants were mildly elevated. Plain radiographs excluded free perforation.

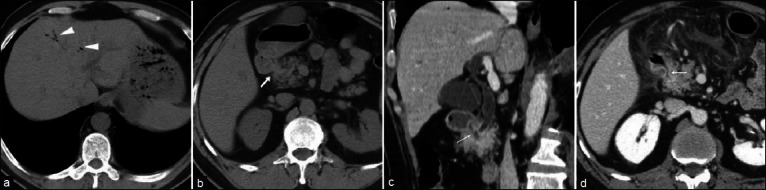

Persistent symptoms prompted urgent computed tomography (CT). Minimal biliary dilatation was identified, with normal gallbladder, intrahepatic ductal air [Figure 1a], adhesion between the ventral pancreatic head and posterior proximal duodenum [Figure 1b], thin fluid-like track suggesting choledocho-duodenal fistula (CDF) [Figure 1c].

Figure 1.

Urgent abdominal CT. Unenhanced images detect peripheral intrahepatic pneumobilia (arrowhead in a), overdistended stomach, and focal adhesion between posterior wall of the proximal duodenum and ventral aspect of the pancreatic head (thick arrow in b). After intravenous contrast administration, detailed oblique-reformatted image (c) shows thin fluid-like communication consistent with choledocho-duodenal fistula (arrow). No abnormalities were detected in the gallbladder. Three days later, during acute pancreatitis repeat CT (d) detects appearance of peripancreatic effusion, confirms fluid-containing fistulous track between the posterior duodenal bulb and the distal common bile duct (thin arrow)

Endoscopy revealed chronic peptic duodenal bulb deformation without active ulcers and fistulous orifices. After unsuccessful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), clinical conditions worsened with acute pancreatitis. Repeat CT detected peripancreatic fluid, increasing pneumobilia, persistent CDF [Figure 1d]. Symptoms resolved during 4-months antiulcer therapy.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous pneumobilia suggests bilioenteric communication, most usually cholelithiasis-related gallbladder perforation into normal duodenum. Conversely, the uncommon (3.5-10% of cases) CDF results from bulb ulcer penetrating the choledochus.[1–5]

Reflecting distribution of peptic disease, CDF manifests with pain, malaise or hematemesis in middle-aged men; jaundice or cholangitis are exceptional.[2,3] Historically, duodenal deformity and biliary opacification during gastrointestinal barium studies identified CDF.[1,5]

Currently, CT detects minimal pneumobilia and differentiates portal venous gas. Additional findings indicating CDF include normal gallbladder, posterior bulb adhesion to ventral pancreas. Conversely, gallbladder mural thickening and intraluminal air shift the diagnosis toward cholecysto-duodenal fistulization. Often impossible because of duodenal narrowing, endoscopy and ERCP may sometimes demonstrate CDF.[3,4]

Antiulcer therapy usually allows clinical improvement and fistula closure. Surgery should be reserved for poorly controlled symptoms, hemorrhage or biliary obstruction.[3,5]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Constant E, Turcotte JG. Choledochoduodenal fistula: The natural history and management of an unusual complication of peptic ulcer disease. Ann Surg. 1968;167:220–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196802000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoppenstein JM, Medoza CB, Jr, Watne AL. Choledochoduodenal fistula due to perforating duodenal ulcer disease. Ann Surg. 1971;173:145–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197101000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaballah S, Sabri Y, Karim S. Choledochoduodenal fistula due to duodenal peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2475–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1012384105644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimono T, Nishimura K, Hayakawa K. CT imaging of biliary enteric fistula. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:172–6. doi: 10.1007/s002619900314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topal U, Savci G, Sadikoglu MY, Tuncel E. Choledochoduodenal fistula secondary to duodenal peptic ulcer. A case report. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:1007–9. doi: 10.1080/02841859709172119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]